Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Larranaga Reflection

Uploaded by

Ic San PedroCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Larranaga Reflection

Uploaded by

Ic San PedroCopyright:

Available Formats

A Reflection on the Larrañaga Case and the Rights to Life and Fair Trial

By Irvin Christian D. San Pedro of 3A

Every human being has the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily

deprived of his life.

The discussion on this provision was brief in Larrañaga. The Human Rights Committee held that

since the Philippines has repealed the death penalty, the allegation of an Article 6 violation is already moot

and no longer needs a discussion. While I do agree with the Committee that the issue was moot then, I do

think that the right to life issue is an important discussion today. With President Duterte calling for the

Congress to reimpose the death penalty, and with the situation of distrust in our country’s judicial (and extra-

judicial) processes, there needs to be a discourse on the right to life. The Larrañaga case, while decided over

ten years ago, has been viral lately with the release of Rappler’s documentary on the case entitled “Give Up

Tomorrow,” which has garnered almost 3 million views in Youtube over the past two months. The discourse

on the right to life is essential not only in raising public awareness in the Duterte regime, but more importantly,

in light of the proposed new Constitution that is being drafted – and the Larrañaga case might just help further

this discourse. For me, the framers of the new Constitution have an opportunity to establish an absolute ban

on the death penalty, i.e. removing the power of Congress to impose death penalty on heinous crimes. This

is in recognition of the spirit behind the right to life, human dignity, which is inherent in every natural person,

including wrongdoers of every kind. While I admit that a Constitutional ban on the death penalty will be

difficult, given that it is contrary to the Duterte agenda, I still think the drafting of the new Constitution that is

taking place today is a rare opportunity for change that may not come again in the next few decades.

In the determination of any criminal charge against him, or of his rights and obligations in a suit at law,

everyone shall be entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal

established by law.

Upon reading the citations of the Committee, and why they held that the Philippines violated Article

14 of the ICCPR in the Larrañaga case, I was reminded of one of the fundamental principles of criminal law

and criminal procedure. In criminal cases, the accused is going up against the State: the powerful and

sovereign State. The accused is in a natural disadvantage. This is partly why there must be rights specifically

for the accused. He must be given a fair trial. He must be presumed innocent. This is also why his guilt must

be proven beyond reasonable doubt before he can be deprived of his liberty, or even life. This is also why in

the construction of penal laws, doubts must be resolved strictly against the State and liberally in favor of the

accused. Given these, I simply cannot help but disagree with the dissent of Committee Member Ms. Ruth

Wedgwood, who thinks that the Committee Majority erred in holding that the Philippines committed human

rights violations in Larrañaga. While I cannot fully discuss Wedgwood’s dissent here, I think that the actions

of the State, in this case the trial court judges who heard Larrañaga’s case, as well as the justices of the

Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court reviewing the case, must be strictly construed against them. For

instance, I agree that there was a human right violation when the trial court refused to grant the newly

appointed counsel’s request for adjournment. Surely, he was unprepared to defend Larrañaga, being

appointed the day before the hearing. The dissent theorizes that the right to speedy trial of the co-accused

would be violated if the adjournment were granted. I disagree. To subject the accused to trial without

adequate preparation for defense for reasons beyond his control cannot be justified under the guise of the

right to speedy trial. The accused is only entitled to the right against undue delay, and in this case, it is due.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- 10 Ways To Care For Our Barristers This NovemberDocument2 pages10 Ways To Care For Our Barristers This NovemberIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- 1.4 SEC V Howey DigestDocument4 pages1.4 SEC V Howey DigestIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- 01 - Te Vs Yu-TeDocument44 pages01 - Te Vs Yu-TeNico GeraldezNo ratings yet

- Jocelyn M. Suazo, Petitioner, vs. Angelito Suazo and Republic of The Philippines, RespondentsDocument23 pagesJocelyn M. Suazo, Petitioner, vs. Angelito Suazo and Republic of The Philippines, RespondentsNico GeraldezNo ratings yet

- Prac Court CaseDocument12 pagesPrac Court CaseErikaNo ratings yet

- HOME - Stabilization Activity ReportDocument1 pageHOME - Stabilization Activity ReportIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- Soriano Doctrines Pt3Document14 pagesSoriano Doctrines Pt3Ic San PedroNo ratings yet

- Bayan Magsiawit Na Kordero NG DiyosDocument3 pagesBayan Magsiawit Na Kordero NG DiyosIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- A L S C C: Teneo AW Chool Hoir Harter Vision-MissionDocument3 pagesA L S C C: Teneo AW Chool Hoir Harter Vision-MissionIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- Appeal Form: QPI in The APPEALED SEMESTER: - Scholar: Subject Without Grades YetDocument2 pagesAppeal Form: QPI in The APPEALED SEMESTER: - Scholar: Subject Without Grades YetAnton MercadoNo ratings yet

- 06 Envelope Page SampleDocument1 page06 Envelope Page SampleIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- Required VotesDocument2 pagesRequired VotesIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- Ideas For Helping Your Choir Sound Like One VoiceDocument4 pagesIdeas For Helping Your Choir Sound Like One VoiceIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- Apprac Buzz 1.1Document3 pagesApprac Buzz 1.1Ic San PedroNo ratings yet

- KELLOGG CO. v. NATIONAL BISCUIT CO. - FindLaw PDFDocument6 pagesKELLOGG CO. v. NATIONAL BISCUIT CO. - FindLaw PDFIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- Apprac Batch 3.2Document36 pagesApprac Batch 3.2Ic San PedroNo ratings yet

- Apprac Batch 3.1Document59 pagesApprac Batch 3.1Ic San PedroNo ratings yet

- Sample Cover Page For Brief For Apprac ClassDocument6 pagesSample Cover Page For Brief For Apprac ClassIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- Apprac Batch 3.1Document59 pagesApprac Batch 3.1Ic San PedroNo ratings yet

- Apprac Batch 3Document41 pagesApprac Batch 3Ic San PedroNo ratings yet

- R119, S20 - R139-B, S2 - Art. 209 RPC - R138 S20e Rules of CourtDocument13 pagesR119, S20 - R139-B, S2 - Art. 209 RPC - R138 S20e Rules of CourtIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- Ethics Conflicts DoctrinesDocument4 pagesEthics Conflicts DoctrinesIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- Transcript of Admin Pubcorp ElectionsDocument14 pagesTranscript of Admin Pubcorp ElectionsIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- Apprac Batch 3.1Document59 pagesApprac Batch 3.1Ic San PedroNo ratings yet

- Sample Brief For Apprac ClassDocument26 pagesSample Brief For Apprac ClassIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- Corp MT MemonotesDocument1 pageCorp MT MemonotesIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- Hofi Corp SynthesisDocument7 pagesHofi Corp SynthesisIc San PedroNo ratings yet

- GSA Civpro SyllabusDocument10 pagesGSA Civpro SyllabusIc San Pedro100% (1)

- Corp Coded Outline 2018Document159 pagesCorp Coded Outline 2018Ic San PedroNo ratings yet

- Corp Notes April 16Document2 pagesCorp Notes April 16Ic San PedroNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Oscar A. Harrison v. Otto C. Boles, Warden of The West Virginia Penitentiary, Moundsville, West Virginia, 307 F.2d 928, 4th Cir. (1962)Document7 pagesOscar A. Harrison v. Otto C. Boles, Warden of The West Virginia Penitentiary, Moundsville, West Virginia, 307 F.2d 928, 4th Cir. (1962)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lai Kee Peng V Tay Hup LianDocument11 pagesLai Kee Peng V Tay Hup LianAmira NadhirahNo ratings yet

- Neri v. Senate CAPO, Et AlDocument3 pagesNeri v. Senate CAPO, Et AlJ.N.No ratings yet

- Ipl CaseDocument4 pagesIpl CasestephclloNo ratings yet

- Ac Ransom Vs NLRC DigestDocument2 pagesAc Ransom Vs NLRC DigestPMV100% (2)

- Lagcao Vs Labra - DigestDocument2 pagesLagcao Vs Labra - DigestJoseph AlulodNo ratings yet

- Id (E) 981Document11 pagesId (E) 981abhishekray20No ratings yet

- Legal FormsDocument8 pagesLegal FormsSilver GoldNo ratings yet

- Transfer of PropertyDocument13 pagesTransfer of PropertyRockstar KshitijNo ratings yet

- Camlin Pvt. Ltd. Vs National Pencil Industries On 7 November, 1985 PDFDocument9 pagesCamlin Pvt. Ltd. Vs National Pencil Industries On 7 November, 1985 PDFmic2135No ratings yet

- Matrimonial PropertyDocument10 pagesMatrimonial PropertyKatoNo ratings yet

- Comparison of The Icj and The IccDocument2 pagesComparison of The Icj and The IccMhaliNo ratings yet

- 4 Moral AccountabilityDocument3 pages4 Moral AccountabilityCyrelOcfemia100% (1)

- 1.special Power of Attorney - GISELLE CRUSPERO GARCESDocument1 page1.special Power of Attorney - GISELLE CRUSPERO GARCESAsumbrado AngeloNo ratings yet

- Midterm Exam AnswersDocument3 pagesMidterm Exam AnswersTokie TokiNo ratings yet

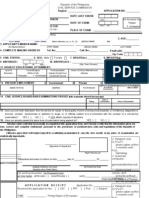

- Civil Service Application FormDocument2 pagesCivil Service Application FormElissa Pagulayan80% (30)

- Loadstar Shipping Co., Inc., Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and The Manila INSURANCE CO., INC., RespondentsDocument10 pagesLoadstar Shipping Co., Inc., Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and The Manila INSURANCE CO., INC., RespondentsJoan ChristineNo ratings yet

- Special Power of AttorneyDocument6 pagesSpecial Power of AttorneyPdean DeanNo ratings yet

- Clat Mock Bank 026014282311bDocument36 pagesClat Mock Bank 026014282311bBhuvan GamingNo ratings yet

- Nolasco Vs EnrileDocument11 pagesNolasco Vs EnrileJay-r ValdezNo ratings yet

- Book Material ForNDMCDocument87 pagesBook Material ForNDMCbijnor officeNo ratings yet

- Tort Law PDFDocument270 pagesTort Law PDFHassan Raza75% (4)

- Token Option Plan ( (Draft) )Document20 pagesToken Option Plan ( (Draft) )Luigi FelicianoNo ratings yet

- Clause 14: Contract Price and Payment: Written by George RosenbergDocument6 pagesClause 14: Contract Price and Payment: Written by George Rosenbergsilence_10007No ratings yet

- The Tamilnadu Survey and Boundaries ActDocument21 pagesThe Tamilnadu Survey and Boundaries ActRavan DemoNo ratings yet

- Xcentric V Goddeau ComplaintDocument11 pagesXcentric V Goddeau ComplaintEric GoldmanNo ratings yet

- 11 - Chapter 4 (Abulencia)Document14 pages11 - Chapter 4 (Abulencia)Wendy Pedron AbulenciaNo ratings yet

- 2016 05 12 Appellant BriefDocument4 pages2016 05 12 Appellant BriefBerteni Cataluña CausingNo ratings yet

- Randy Blackwelder, Alice Blackwelder, Carmon Blackwelder, Katherine Blackwelder, Stephen Standish, Debora Standish, Aaron Standish, George Lonneville, Hilda Lonneville, Amy Lonneville and Jacqueline Lonneville v. Henry Safnauer, in His Official Capacity as the Superintendent of the Cato- Meridian Central School District, Edward Garno, in His Official Capacity as the Superintendent of City School District of Oswego, and Michael Hunsinger, in His Official Capacity as the Superintendent of the Waterloo Central School District, the State of New York, Intervening-Defendant, 866 F.2d 548, 2d Cir. (1989)Document6 pagesRandy Blackwelder, Alice Blackwelder, Carmon Blackwelder, Katherine Blackwelder, Stephen Standish, Debora Standish, Aaron Standish, George Lonneville, Hilda Lonneville, Amy Lonneville and Jacqueline Lonneville v. Henry Safnauer, in His Official Capacity as the Superintendent of the Cato- Meridian Central School District, Edward Garno, in His Official Capacity as the Superintendent of City School District of Oswego, and Michael Hunsinger, in His Official Capacity as the Superintendent of the Waterloo Central School District, the State of New York, Intervening-Defendant, 866 F.2d 548, 2d Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Agustin vs. CaDocument2 pagesAgustin vs. CaBingoheartNo ratings yet