Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Historical Performance of Trend Following

Uploaded by

robjenkinsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Historical Performance of Trend Following

Uploaded by

robjenkinsCopyright:

Available Formats

Historical Performance of Trend Following

Jonathan Duke, Head of Investment Systems

David Harding, Founder and Chairman

Kate Land, PhD, Senior Scientist

Winton Capital Management December 2013

T rend following is a well known trading strategy in

which market forecasts are based solely on

recent price movements. We document the

performance of such strategies for a portfolio of large

futures markets since the mid‐1980s, and consider if

that can be used to explain the returns of any stock or

portfolio, along with the market, value, and size factors

[4, 5]. As it becomes better documented, returns from

momentum signals are increasingly deemed to be ῾beta᾿

there is any dependence on trading speed. In general rather than ῾alpha᾿ in the world of equities.

we find trend following systems to be effective in In this study we document the performance of trend

forecasting future price movements, but we observe a following strategies for different time horizons on data

significant and persistent decline in the forecasting from the mid‐1980s until today. Within the financial

ability of those with the fastest turnover. markets great efforts are ongoing to achieve the fastest

possible communication speeds with exchanges,

1 Introduction contributing to a perception that fastest is always best.

However we find evidence that fast has not always been

There is a long history of practitioners within the

best in the world of trend following and futures markets,

financial markets using ῾technical analysis᾿ to take

where we see a significant decline in the performance of

investment decisions based on patterns in historical

the fastest strategies even before transaction costs are

price data. These ideas became popular within the

accounted for. In Section 2 we outline the markets that

futures markets where professional investment advisors

we use to document this effect and the rules of our

operate under the rubric of ῾Commodity Trading Advisor῾

trend following trading system. In Section 3 we

(CTA). The acronym CTA has now become almost

document our results, and we conclude with a

synonymous with ῾trend following῾ or ῾momentum῾

discussion in Section 4.

strategies, where the pattern in question is simply

whether a market price has risen or fallen in recent

2 Data and Methodology

history. This tendency for prices to trend is described in

statistical terms as ῾auto‐correlation῾ of returns. Futures

It is only in recent history that trend following on

major asset classes, via futures markets, has gained the We use the front contract for 20 futures markets which

attention of the academic community [1]. The focus of are representative of their sector, highly liquid, global in

academic work has been on equity markets, where their reach, and have a long history. The markets are

momentum is most commonly embodied as a cross‐ listed in Table 1. For the subsequent analysis, we use the

sectional effect used to predict relative, rather than date range 1 Jan 1984 to 31 Oct 2013, and therefore we

absolute, returns of stocks [2, 3]. In this guise it still have nearly 30 years of results. 15 of our 20 assets have

however exploits the existence of auto‐correlation in started trading by Jan 1984, and 18 by Sept 1986 and all

returns, relative to the market. The evidence for 20 by Sept 1988 (Bunds is the last to start).

momentum in equity prices is strong enough that it is It is tempting to synthesise futures prices prior to

now accepted as one of the standard equity ῾risk factors᾿ these start dates in order to perform a longer historical

Working Paper Winton Capital Management Page 1 of 7

Figure 1: The gross performance (not compounded) and the realised volatility (determined by a 100 day exponentially‐weighted estimate) for

our three trend following strategies. The Sharpe ratios (SR) are 0.87, 1.12, and 0.81 for the fast, medium, and slow strategies respectively for

the above 30 year time period (the standard error on the SR is approximately 0.2 for 30 years of data). The realised volatility is around 10.5%

for all three strategies.

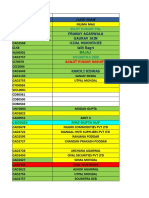

Fixed Inc Indices FX Commodities As well as the per‐asset PL results, we consider the

10y Tnote S&P500 Euro Gold results of a portfolio of the 20 assets. The portfolio is

Eurodollar Nikkei3 JYen Live Cattle simply a linear combination of the per‐asset PL streams,

Bunds1 Hang Seng4 BPound Copper7,8 with equal weights. Recall that each asset achieves

JGB2 ASX2005 SFranc WTI Oil

approximately the same volatility due to the volatility

Bonds FTSE6 CDollar Corn

scaling of the positions, and we achieve approximately

Table 1: The 20 futures in our trend following portfolio. These are

(now) traded on the CME except: 1Eurex; 2TSE; 3OSE; 4HKFE; 5SFE;

equal sector risk because we have 5 markets per sector.

6

LIFFE; 7LME; 8we synthesise prices for a Copper futures contract with We remain free to apply a final overall scaling to all the

a fixed expiry date, rather than a fixed time to expiry as found on the positions in order to achieve a desired volatility at the

LME.

portfolio level.

simulation. For the purpose of this paper we wish our Returning to the moving‐average cross‐over system,

results to be free from any uncertainty regarding the there are two important parameters: the short and long

validity of such an extrapolation. Similarly, we restrict periods of the ewmas. These determine the effective

ourselves to results since Jan 1984, when most of our look‐back time and holding period, although this is not

markets have started, in order to avoid the effects a how the system is specified. We will consider three

changing number of assets can have on the portfolio‐ different trend following systems of different speeds,

level performance. called ῾fast᾿, ῾medium᾿, and ῾slow᾿, which have a turnover

of 1, 6, and 13 weeks respectively1. The fast system is

correlated 26% and 5% to the medium and slow systems

Trading system

respectively, and these have a 34% correlation to each

other. Note that our systems trade every day, regardless

We use an exponentially weighted moving‐average

of speed.

(ewma) cross‐over system (the difference between a

fast and a slow ewma of the price) to determine

whether we go long or short in a market; we are long

when the fast average is above the slow and vice versa.

The positions are scaled by the inverse of a 20 day 1

We define the turnover of a system as the ratio of the

exponentially weighted estimate of volatility, which has

mean absolute position to the mean absolute 5 day

the effect of keeping the volatility of the final ῾profit and change in position, roughly indicating how many weeks it

loss᾿ time series (PL) approximately constant with time takes to close a position but ignoring small trades back and

for a single asset, and equal between assets. forth on a daily level.

Working Paper Winton Capital Management Page 2 of 7

Figure 2: The gross performance of the portfolio in six separate 5 year periods (84‐88, 89‐93, ..., 09‐13), for our three trend following

strategies. The standard error of these estimates is shown in grey around the results of the medium strategy. Dashed lines give the

average SR for the individual asset PL; these appear to mimic the performance of the portfolio, indicating that the decline at the

portfolio level is due to the decline of performance of underlying assets and not an increase in between‐asset correlation.

Another way of implementing a momentum strategy

Speed 84‐93 94‐03 04‐13 ∆ t p

is to look at the past return for some look‐back period Fast 1.85 0.85 0.00 1.85 4.2 <0.01%

and then hold a position (long or short according to the Medium 1.54 1.18 0.70 0.84 1.9 3%

sign of the return) for some holding period, as Slow 0.95 0.94 0.57 0.38 0.9 20%

implemented in [1]. In Section 3 we check our results Table 2: Ten year gross SR for our strategies, where ∆ is the

difference between the first and last 10y periods, and t and p are the

against this alternative implementation, and generally

corresponding t‐statistic and p‐value. The p‐value estimates the

find the results to be similar (at the same turnover level). probability of achieving the observed $\Delta$ value under the null

In this study we focus on gross performance, in order hypothesis that the true performance did not change in these two ten

year periods, and the difference is just due to sample error. All

to simply document the historical properties of futures strategies have seen a decline in performance, but this is most

price series. We do not attempt to translate these significant for the fastest system.

results into Net PL. That is, we are not including

Figure 2, and further examined in Table 2. The fastest

transaction costs (broker commission and slippage), fees

strategy has seen a significant decline in performance,

(performance and management), or any earned interest

and we can rule out with a probability <0.0001 that the

in our simulations.

SR in the first and last 10 year periods have come from a

distribution with the same mean.

Second we look at the performance of the systems at

3 Results

the asset level. The decline in risk‐adjusted performance

First we look at the results of the portfolio of 20 markets. at the portfolio level, as seen in Figure 2, could be due to

In Figure 1, we see that all three strategies have increased correlations between the constituent asset PL,

performed well, with annualised Sharpe ratios2 of 0.81 reducing the diversification and causing one to scale

or higher for this 30 year period. However, we can see down one’s positions in order to achieve the same

that the performance of the fast strategy has declined, annualised volatility at the portfolio level, or a decline in

having initially outperformed the others but remaining per‐asset performance, or a mixture of both. In Figure 2

flat since 2004. This is even clearer once we compute we see that the average per‐asset performance has

the SR for different time periods, as can be seen in declined in an identical fashion to the portfolio

performance, confirming that this is the main cause of

the portfolio‐level decline. To double‐check this we also

2

The Sharpe ratio (SR) is a measure of risk‐adjusted return, consider how the correlation of the per‐asset PL has

PL / PL . It is generally measured with changed over time. We find the average correlation is

respect to a benchmark $R_f$, such as the risk free rate. ∼4% (84‐88) and rises to ∼7% (09‐13), and this is true

However, in this study we do not use a benchmark in our

for the 3 different trading speeds. The risk‐adjusted

SR calculations.

Working Paper Winton Capital Management Page 3 of 7

Figure 3: Five year gross SR results for randomly selected portfolios of 20 markets (selected from a total list of 38). Plotted are the median results

for each strategy speed, and the 15 ‐ 85th percentile ranges from 1,000 realisations.

performance of an equally weighted portfolio of fast, medium, and slow ewma cross‐over strategies

assets can be estimated as respectively; they have similar turnover levels (1, 6, and

13 weeks) and are correlated approximately 80% to the

√ corresponding ewma strategy. The results for this

(1)

1 1 ̄ implementation are as follows:

where is the average risk‐adjusted performance of Speed 84‐93 94‐03 04‐13

the assets. With this we can estimate the effect the Fast 1.38 0.39 ‐0.01

Medium 1.19 1.07 0.59

increase in correlation has on the portfolio level

Slow 1.26 0.91 0.60

performance, and we find the multiplicative factor goes

from 3.4 to 2.9. Therefore, had the per‐asset results not We see the same feature ‐ with performance declining

changed over time, the increased correlations would overall, and most significantly for the fast strategy. We

alone cause a relative decline of about 15%. This is not therefore think our results are robust to the exact

much compared to the relative decline that we actually implementation details of a momentum driven strategy.

observe (100% for the fastest system). We next consider the robustness of our results to the

markets that we have used, as listed in Table 1. We

Further analysis

extend our potential portfolio by another 18 markets (5

We consider an alternative implementation of a trend in fixed‐income, commodities, indices, and 3 in

following strategy, where instead of a price moving‐ currencies)3 and we randomly choose a subset of 20

average cross‐over signal, we simply look at the past markets from these 38 and repeat the analysis for the

return for some look‐back period and use this to fast, medium, and slow ewma cross‐over systems. In

determine the sign of our position. We then hold any Figure 3 we plot the median and 15‐85 percentile range

position (which will also be inverse volatility scaled) for a for the results from 1,000 random portfolio choices for

certain holding period. However, we will have a number each sped of system. We find the overall result robust to

of positions open at any time if the holding period is selection of the markets; the performance is seen to

greater than 1 day, and we sum over these at any time

to evaluate our daily PL. We restrict ourselves to the 3

Lean Hogs, Silver, Natural Gas, Soy Beans, Aluminium, DJ

parameter space where the holding period is half of the Eurostoxx, Dax, Kospi, Nasdaq, the Hang Seng China

look‐back period. We find look‐back periods of 2 weeks, Enterprises Index, Euribor, Short sterling, Bobl, 5Y T‐notes,

1 quarter, and 1 year (and holding periods of 1 week, 33 Schatz, Australian Dollar, Mexican Peso, New Zealand

days, and 6 months) approximately correspond to the dollar

Working Paper Winton Capital Management Page 4 of 7

decline, particularly for the fastest strategy. A glaring omission from this study is the issue of

Although we do not want our analysis to rest heavily transaction costs which could be a major factor in the

on synthesised data, we consider one very long time ultimate profitability of these strategies. Instead we

series: that of the Dow Jones Industrial Average stock have concentrated on the raw effect size, and have not

index. This index was first calculated in 1896. However, attempted to make any claims as to the potential

futures on the index have only existed since 1997, and economic usefulness of it. In order to understand the

therefore we synthesise a rolled futures series using economic significance it is necessary to consider

dividend yields and interest rates going back to 1900. brokerage fees, market impact (or slippage) and any

We then simulate the hypothetical results of trading our other associated costs. Furthermore in the context of

original fast, medium, and slow ewma trend following this study it would be necessary to understand how

strategies on this DJIA price series. We find results over these costs have varied through time. Since this would

this very long time period that support the hypothesis require many more assumptions we decided that it

that performance has declined for the fastest strategy: would detract from the simplicity and clarity of this

study, although we appreciate that costs could be

Speed 00‐23 24‐53 54‐83 84‐13 substantial.

Fast 0.98 0.86 1.03 ‐0.10 We have also not included interest in these

Medium 0.55 0.51 0.43 0.08 simulations; investors of CTA Funds typically earn the

Slow 0.01 0.43 0.15 0.43 risk‐free rate on the cash that they do not require to

margin positions. This can be around 90% of assets and

The medium strategy has seen a less sharp decline than

therefore this would improve the performance of the

the fast strategy, and the slow performance is fairly flat.

For reference, the standard error on a 30 year SR is total investment significantly. This is true especially in

approximately 0.2. the past when the risk‐free rate was higher than today.

We have also not included management or performance

fees in the simulations as they are not relevant for this

4 Discussion study (having had a consistent effect over time).

We have not yet speculated about the causes of the

Momentum is increasingly getting the stamp of approval decline in performance, but many would note that it

from the academic community as one of several factors coincides with a rise in assets under management in the

that can explain both the risk and return of equity CTA industry. Three possible explanations for a

prices [5] and more generally the returns of asset weakening of the momentum effect are:

prices [1]. Its existence is controversial as illustrated by 1. A growing volume of assets seeking to profit from

the words of Eugene Fama; “Of all the potential the effect. The exact mechanics of how this might

embarrassments to market efficiency, momentum is the weaken performance are beyond the scope of this

primary one” [7]. discussion, but such an argument would be based on the

At the same time as receiving academic attention, premise that the more people who know about an

mainstream institutional investors have embraced ῾opportunity᾿ in financial markets, the less likely it is to

momentum strategies. This is illustrated by the growth persist. This explanation is consistent with the growth of

of assets in the CTA industry and the proliferation of the CTA industry.

products that seek to profit specifically from a 2. A reduction in transaction costs. An efficient

momentum or trend following effect. market perspective would argue that predictable effects

In this paper we have gone beyond just documenting can exist, provided they are not exploitable after costs.

the existence of a trend following effect in futures Viewed from this perspective a steady reduction in

markets, and have explored how consistent it has been transaction costs over the last 40 years could explain the

through time. In particular, we find evidence that the reduction in effect size. Whilst the experience of the

strength of fast trend following strategies has declined authors as practitioners within the CTA industry is at

significantly over time. Our results are robust to the odds with an efficient market perspective, nothing in

markets we use and the parameterisation of the system.

Working Paper Winton Capital Management Page 5 of 7

this paper discredits this being either a partial or [5] E.F.Fama, K.R.French, Size, Value, and Momentum

complete explanation. in International Stock Returns, Journal of Financial

3. A change in the behaviour of market participants. Economics, vol 105, 457‐472 (2012).

The first two possible explanations are endogenous to [6] E.Cusworth, CTA trend followers suffer in a market

those who seek to exploit this effect. It is possible that dominated by intervention, Risk.net (2013)

some exogenous change is responsible. Indeed the [7] E.F.Fama, R.Litterman, An Experienced View on

recent poor performance of trend following strategies Markets and Investing, Financial Analysts Journal, vol

has been attributed to the intervention of central banks 68 (2012)

curtailing trends in markets [6].

These three explanations are purely speculative and

as such we do not seek within this paper to suggest

which, if any, of them is the most plausible. It is also not

possible to extrapolate our results into the future with

any confidence. All we can say is that the strength of the

momentum effect has not been historically stable, and

so we have no reason to think it will be in future. Taking

all the data at face value the outlook is unclear, except

that our results suggest that fast is not always best, and

perhaps patience is rewarded.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Winton research department for

help with the simulations and data, as well as many

useful discussions on this topic over a number of years.

With particular thanks to Matthew Beddall, and Tom

Babbedge, for their valuable insights.

For correspondence please email

researchpapers@wintoncapital.com

References

[1] T.J.Moskowitz, Y.H.Ooi, L.H.Pedersen, Time series

momentum, Journal of Financial Economics, vol 104,

228‐250 (2012)

[2] N.Jegadeesh, S.Titman, Returns to Buying Winners

and Selling Losers: Implications for Stock Market

Efficiency, Journal of Finance, vol 48 (1993)

[3] A.W.Lo, A.C.MacKinlay, When Are Contrarian

Profits Due to Stock Market Overreaction?, Review of

Financial Studies, vol 3, 175‐205 (1989)

[4] M.M.Carhart, On Persistence in Mutual Fund

Performance, Journal of Finance, vol 52, 57‐82 (1997)

Working Paper Winton Capital Management Page 6 of 7

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

This document has been prepared by Winton Capital Management Limited (“WCM”), which is authorised

and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered as an investment adviser with the US

Securities and Exchange Commission, registered with the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission

and a member of the National Futures Association.

This document is provided for information purposes only and the information herein does not constitute an

offer to sell or the solicitation of any offer to buy any securities.

The information herein is subject to updating and further verification and may be amended at any time and

WCM is under no obligation to provide an updated version. WCM has used information in this document

that it believes to be accurate and complete as of the date of this document. However, WCM does not

make any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the information’s accuracy or

completeness, and accepts no liability for any inaccuracy or omission. No reliance should be placed on

the information herein and WCM does not recommend that it serves as the basis of any investment

decision.

This document may contain results based on simulated or hypothetical performance results that have

certain inherent limitations. Unlike the results shown in an actual performance record, such results do not

represent actual trading. Also, because such trades have not actually been executed, these results may

have under- or over-compensated for the impact, if any, of certain market factors, such as lack of liquidity.

Simulated or hypothetical trading programs in general are also subject to the fact that they are designed

with the benefit of hindsight. No representation is being made that any investment will or is likely to

achieve profits or losses similar to those being shown using simulated data.

Unauthorised dissemination, copying, reproducing or transmitting of this information is strictly prohibited.

©Winton Capital Management Limited 2014. All rights reserved.

Working Paper Winton Capital Management Page 7 of 7

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- PCI Leasing and Finance Vs Giraffe-X Creative ImagingDocument4 pagesPCI Leasing and Finance Vs Giraffe-X Creative ImagingBernadetteGalera100% (1)

- WN - 1 Resource Test WN-2 Shares Outstanding TestDocument8 pagesWN - 1 Resource Test WN-2 Shares Outstanding TestSimran KhandujaNo ratings yet

- Overview of Vie Tin BankDocument2 pagesOverview of Vie Tin BankTran DatNo ratings yet

- Stock Portfolio Tracker (Blueprint)Document76 pagesStock Portfolio Tracker (Blueprint)DansNo ratings yet

- BBB Case Write-UpDocument2 pagesBBB Case Write-UpNeal Karski100% (1)

- Toughened Glass InvoiceDocument1 pageToughened Glass InvoiceGK TRADINGNo ratings yet

- Business Maths Summary1Document3 pagesBusiness Maths Summary1EmilyNo ratings yet

- Tarak (Z100)Document564 pagesTarak (Z100)Tarak PaulNo ratings yet

- Axis Nifty 100 Index Fund - NFODocument12 pagesAxis Nifty 100 Index Fund - NFOhammarworldNo ratings yet

- Small and Medium-Sized Entities (Smes) : Page 1 of 6Document6 pagesSmall and Medium-Sized Entities (Smes) : Page 1 of 6globeth berbanoNo ratings yet

- Commercial Banking vs. Investment BankingDocument23 pagesCommercial Banking vs. Investment Bankingpranav2411No ratings yet

- Probabilistic Methods for Pricing Bonds and DerivativesDocument89 pagesProbabilistic Methods for Pricing Bonds and DerivativesWarren CullyNo ratings yet

- International Standard of AuditingDocument4 pagesInternational Standard of AuditingSuvro AvroNo ratings yet

- Elysium Capital India Commentary 090609Document2 pagesElysium Capital India Commentary 090609oontiverosNo ratings yet

- Accounts 2Document41 pagesAccounts 2SubodhSaxenaNo ratings yet

- Offshore: Offshore Banking - Deposit of Funds by A Company or An Individual in A Bank That Is Located Outside NationalDocument4 pagesOffshore: Offshore Banking - Deposit of Funds by A Company or An Individual in A Bank That Is Located Outside NationalChristine Joy LacsonNo ratings yet

- Disney Pixar CIADocument4 pagesDisney Pixar CIAMridul LuthraNo ratings yet

- MFMRI. Commerce Faculty BHU, Placement ReportDocument3 pagesMFMRI. Commerce Faculty BHU, Placement ReportALOK KUMAR100% (1)

- Implementing SAK ETAP Standards in Village Credit Institutions (LPDsDocument5 pagesImplementing SAK ETAP Standards in Village Credit Institutions (LPDsDayu MirahNo ratings yet

- Malaysia Capital Market MasterplanDocument15 pagesMalaysia Capital Market MasterplanislamiceconomicsandfinanceNo ratings yet

- FR SBPDocument10 pagesFR SBPkandagatla prudhviiNo ratings yet

- Kepco's Claim for Tax Refund Dismissed Due to Non-Compliance of Substantiation RequirementsDocument2 pagesKepco's Claim for Tax Refund Dismissed Due to Non-Compliance of Substantiation RequirementsJeremiah Trinidad100% (2)

- SC Rules on Petron Privatization CaseDocument13 pagesSC Rules on Petron Privatization CaseptbattungNo ratings yet

- Banking & Economy PDF 2019: Key UpdatesDocument103 pagesBanking & Economy PDF 2019: Key UpdatesParvesh GargNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Stock ExchangeDocument34 pagesIntroduction To Stock ExchangevivekdograNo ratings yet

- DisposalDocument107 pagesDisposaljohnisflyNo ratings yet

- TYPES OF ACCOUNTING AND FINANCIAL CONCEPTSDocument83 pagesTYPES OF ACCOUNTING AND FINANCIAL CONCEPTSTawanda MahereNo ratings yet

- Factsheet: Deutsche Bank Best Allocation - Flexible: Investment PolicyDocument6 pagesFactsheet: Deutsche Bank Best Allocation - Flexible: Investment PolicyFelixNo ratings yet

- Rama Udyog Private Limited November 03, 2020: Rating Instrument / Facility Amount (Rs. Crore) Rating Rating ActionDocument4 pagesRama Udyog Private Limited November 03, 2020: Rating Instrument / Facility Amount (Rs. Crore) Rating Rating ActionRAMODSNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7Document15 pagesChapter 7BismahMehdi100% (1)