Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Structure of Language

Uploaded by

api-4066584770 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

49 views3 pagesOriginal Title

structure of language

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

49 views3 pagesStructure of Language

Uploaded by

api-406658477Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

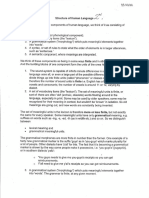

Structure of Human Language

Handout for LING 057

Language and Popular Culture.

When we think about the components of human language, we think of it

as consisting of the following:

1. A sound-system (or phonological component).

2. A set of vocabulary items (the "lexicon").

3. A grammatical system ("morphology") which puts meaningful

elements together into 'words'.

4. A syntax, or set of rules to state what the order of elements is in

larger utterances, such as 'sentences.'

5. A semantic component, where meanings are interpreted.

We think of these components as being in some ways finite and in other

ways non-finite. And the building blocks of one component form the

units of the ones higher than it.

1. The sound-system is capable of infinite minute differences in sound,

but no language uses all, or even a large part of the possible

differences. Sound systems divide things up into finite units (called

"phonemes" or classes of sounds) and therefore the number of sound

units is finite i.e. English has a finite number of vowels and

consonants; the number of vowels is around 11 or 12, varying by

dialect.

2. A set of vocabulary items (the "lexicon"). The set of meaningful

units is finite, or sort of: there are often 'old' (archaic, obsolete)

words floating around in the language, especially in print. Some may

be used by older speakers; some may be recognized for their

meaning in context, but wouldn't be 'known' in isolation. So old

meanings are going out, and new words are constantly being

invented.

The set of meaningful units in the lexicon is therefore more or less

finite, but not exactly the same for every speaker. Some meaningful

units have only grammatical meaning, e.g. suffixes on words such

as -ing, -s, -ed, -th (as in width etc.) and so on. So we distinguish

between

lexical meaning and

grammatical meaningful units.

The grammatical morphemes are more finite in number than the

former. One example of a fairly new grammatical marker is the

suffix 'guys' as in 'you-guys' which marks plurality for a lot of

people. Other dialects have 'y'all' for this. The fact that it is

becoming a grammatical marker is shown by the way some people

make it possessive, i.e. 'you-guys's' [yugayzIz], or in southern

dialects 'yallz':

'You guys needs to give me you-guys's receipts so you can get

reimbursements.

Y'all need to give me y'all's receipts so you can get

reimbursements.

3. A grammatical system ("morphology") which puts meaningful

elements together into 'words'. The grammar is finite, at any given

moment.

4. A syntax, or set of rules to state what the order of elements is in

larger utterances, such as 'sentences.' But the output of the syntax,

i.e. the sentences people know and recognize, is infinite.

5. A semantic component, where meanings are interpreted. Number of

possible meanings is probably also infinite.

Put these together in a kind of hierarchical structure, using the sound

system as the first building blocks and working upward from there,

gives us the following structure:

Level of structure: Possibilities:

Semantics: Infinite.

Syntax: sentences INFINITE

Grammar: rather rigid and fixed.

finite

Innovation at this level is slow

Vocabulary, meaningful units:

finite

somewhat open-ended, but essentially

Sound system, units of sound finite

Phonetic level Infinite

We see this kind of structure, built from the ground up, as possessed

solely by humans, and not observed for other animals, even primates

such as chimps, gorillas, etc. The structure of their communication

system is much simpler: fewer 'vocabulary' items, simple syntax, very

little innovation.

haroldfs@ccat.sas.upenn.edu

You might also like

- Structure and Components of Human LanguageDocument2 pagesStructure and Components of Human LanguageHellaNo ratings yet

- Theoretical GrammarDocument16 pagesTheoretical GrammarХристина Замківська100% (2)

- 736 - Unit 1 ReaderDocument11 pages736 - Unit 1 ReaderElene DzotsenidzeNo ratings yet

- Gram Cheat SheetDocument24 pagesGram Cheat SheetXénia RNo ratings yet

- Human Language PropertiesDocument4 pagesHuman Language Propertieswendy nguNo ratings yet

- The Physical Foundation of Language: Exploration of a HypothesisFrom EverandThe Physical Foundation of Language: Exploration of a HypothesisNo ratings yet

- Lexicology LecturesDocument43 pagesLexicology LecturesСашаNo ratings yet

- ЛЕКЦ ТЕОРГРАМ Для СтудентовDocument30 pagesЛЕКЦ ТЕОРГРАМ Для СтудентовNilufarxon TeshaboyevaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Linguistics (A Full Course) Notes by TarikDocument35 pagesIntroduction To Linguistics (A Full Course) Notes by TarikSimo MijmijNo ratings yet

- Linguistics Applied to Language Teaching: Functions of LanguageDocument7 pagesLinguistics Applied to Language Teaching: Functions of LanguageMonica AnticonaNo ratings yet

- Origin of LangugeDocument43 pagesOrigin of LangugelicibethNo ratings yet

- Part I, Lesson IDocument6 pagesPart I, Lesson IGomer Jay LegaspiNo ratings yet

- Introduction To LinguisticsDocument4 pagesIntroduction To LinguisticsRomnick Fernando CoboNo ratings yet

- LingwistykaDocument1 pageLingwistykaAnia SiminskaNo ratings yet

- 1.language Levels and Word MeaningDocument7 pages1.language Levels and Word Meaningsemenal2907No ratings yet

- Тема 1. Systemic character of language 1.1. The notion of grammarDocument12 pagesТема 1. Systemic character of language 1.1. The notion of grammarВалерия БеркутNo ratings yet

- PsycholinguisticsDocument11 pagesPsycholinguisticsAsmaa BaghliNo ratings yet

- ApuntesDocument42 pagesApuntesAna Martínez RamonNo ratings yet

- Linguistic-Mokhtasara-Blida - PDF Version 1 PDFDocument33 pagesLinguistic-Mokhtasara-Blida - PDF Version 1 PDFjojoNo ratings yet

- Linguistics Assignment 1Document12 pagesLinguistics Assignment 1Hafiz Muhammad HananNo ratings yet

- Syntax vs. Diction: What's The Difference?: Syntax and Diction Are Different Concepts in Grammar and in LiteratureDocument7 pagesSyntax vs. Diction: What's The Difference?: Syntax and Diction Are Different Concepts in Grammar and in LiteratureSam MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Gramatica Inglesa ApuntesDocument24 pagesGramatica Inglesa Apuntesadiana.s2002No ratings yet

- 01.curs Introductiv MorfoDocument5 pages01.curs Introductiv MorfoVlad SavaNo ratings yet

- MORPHOLOGYDocument11 pagesMORPHOLOGYnguyenthikieuvanNo ratings yet

- HandoutsDocument2 pagesHandoutsKitel Tonoii ÜNo ratings yet

- The Object and Main Problems of LexicologyDocument4 pagesThe Object and Main Problems of LexicologyVania PodriaNo ratings yet

- Intro 2 Ling L1 The Sounds of Language Part 1Document7 pagesIntro 2 Ling L1 The Sounds of Language Part 1CHERRYLOU GOZONo ratings yet

- Course 1-2 Language and Linguistics-TotDocument48 pagesCourse 1-2 Language and Linguistics-Totmihai dimaNo ratings yet

- PhonemDocument15 pagesPhonemMega PuspitaNo ratings yet

- Part 1 - LiDocument12 pagesPart 1 - LiFarah Farhana Pocoyo100% (1)

- Basic Linguistic NotionsDocument33 pagesBasic Linguistic NotionsЕвгения ХвостенкоNo ratings yet

- Human LanguageDocument4 pagesHuman LanguagePhương MaiNo ratings yet

- Intro To LinguisticsDocument4 pagesIntro To LinguisticsAlfredo SapaoNo ratings yet

- Limbaj de SpecialitateDocument10 pagesLimbaj de SpecialitateMarta TrifașNo ratings yet

- What is semantics aboutDocument30 pagesWhat is semantics aboutSwagata RayNo ratings yet

- Lexicology Week 1 2020Document3 pagesLexicology Week 1 2020liliNo ratings yet

- THe Idiolect, Chaos and Language Custom Far from Equilibrium: Conversations in MoroccoFrom EverandTHe Idiolect, Chaos and Language Custom Far from Equilibrium: Conversations in MoroccoNo ratings yet

- What Is PsycholinguisticsDocument5 pagesWhat Is Psycholinguisticselsa safitriNo ratings yet

- What Is The Contribution To Linguistics of Ferdinand de SaucierDocument10 pagesWhat Is The Contribution To Linguistics of Ferdinand de SaucierRebeca OliveroNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 MorphologyDocument12 pagesUnit 2 MorphologySofia SanchezNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Language: Key PointsDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Language: Key PointsLorraine Lagos PizanoNo ratings yet

- Volkova Theoretical GrammarDocument30 pagesVolkova Theoretical GrammarEugen DrutacNo ratings yet

- Language Skills and Communication:: The Evolutionary Progress and Rapid DevelopmentFrom EverandLanguage Skills and Communication:: The Evolutionary Progress and Rapid DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Birdsong Syntax and LinguisticsDocument9 pagesBirdsong Syntax and Linguisticsyip100236No ratings yet

- Aspects of human language propertiesDocument4 pagesAspects of human language propertiesMohamed El Moatassim Billah100% (1)

- Seminar 2Document14 pagesSeminar 2Христина ВінтонякNo ratings yet

- Understanding the key concepts of knowing a word, lexical storage and access, and issues in listeningDocument4 pagesUnderstanding the key concepts of knowing a word, lexical storage and access, and issues in listeningShanti.R. AfrilyaNo ratings yet

- ISIDocument42 pagesISIZumrotul UluwiyyahNo ratings yet

- Phonology Is The Level That Deals With Language Units and Phonetics Is The Level That Deals With Speech UnitsDocument31 pagesPhonology Is The Level That Deals With Language Units and Phonetics Is The Level That Deals With Speech UnitsДаша МусурівськаNo ratings yet

- 1-4 тестDocument15 pages1-4 тестДаша МусурівськаNo ratings yet

- thayhaintrolingDocument10 pagesthayhaintrolingHoàng Quốc TuấnNo ratings yet

- Intro To LinguisticsDocument35 pagesIntro To Linguisticsirene casipitNo ratings yet

- Three Figures of SpeechDocument14 pagesThree Figures of SpeechwisdomNo ratings yet

- Dynamika Slovnej ZásobyDocument13 pagesDynamika Slovnej ZásobyZuzka17No ratings yet

- 1st and 2ndDocument5 pages1st and 2ndmosab77No ratings yet

- Why the syllable is the smallest articulatory and perceptible unitDocument5 pagesWhy the syllable is the smallest articulatory and perceptible unitZhania NurbekovaNo ratings yet

- Morphology UuDocument31 pagesMorphology UuLaksmiCheeryCuteizNo ratings yet

- Wri 207 Proposal MemoDocument1 pageWri 207 Proposal Memoapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Wri 207 Business Plan FinalDocument7 pagesWri 207 Business Plan Finalapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Novel Feedback For PortfolioDocument2 pagesNovel Feedback For Portfolioapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Pro Con Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesPro Con Lesson Planapi-406658477No ratings yet

- New Tech Tools Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesNew Tech Tools Lesson Planapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Wordart LessonDocument3 pagesWordart Lessonapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Google Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesGoogle Lesson Planapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Campus Speaker Scenario 2Document5 pagesCampus Speaker Scenario 2api-406658477No ratings yet

- Reporting Article FinalDocument4 pagesReporting Article Finalapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Hootsuite CertDocument1 pageHootsuite Certapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Profile Article MagazineDocument4 pagesProfile Article Magazineapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Trust Fall Workshop 1 RevisionDocument15 pagesTrust Fall Workshop 1 Revisionapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Genre Web Lesson PlanDocument11 pagesGenre Web Lesson Planapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Dewey Decimal Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesDewey Decimal Lesson Planapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Pro Con Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesPro Con Lesson Planapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Adobe Spark Lesson Plan-2Document8 pagesAdobe Spark Lesson Plan-2api-406658477No ratings yet

- Citation Practice MlaDocument6 pagesCitation Practice Mlaapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Mla In-Text Citation LessonDocument11 pagesMla In-Text Citation Lessonapi-406658477No ratings yet

- December Library NewsletterDocument2 pagesDecember Library Newsletterapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Graphic Organizer TemplateDocument3 pagesGraphic Organizer Templateapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Library PromotionDocument1 pageLibrary Promotionapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Pro Con Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesPro Con Lesson Planapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Directions For Directions Quiz LessonDocument12 pagesDirections For Directions Quiz Lessonapi-406658477No ratings yet

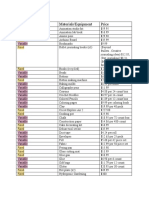

- Makerspace Equipment For Econ ClassDocument2 pagesMakerspace Equipment For Econ Classapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Adobe Spark Lesson Plan-2Document8 pagesAdobe Spark Lesson Plan-2api-406658477No ratings yet

- How To Access FlipgridDocument1 pageHow To Access Flipgridapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Cricut Lunch and Learn Lesson Plan-2Document2 pagesCricut Lunch and Learn Lesson Plan-2api-406658477No ratings yet

- Basic Nearpod InstructionsDocument1 pageBasic Nearpod Instructionsapi-406658477No ratings yet

- Application For Library Club MembershipDocument2 pagesApplication For Library Club Membershipapi-406658477No ratings yet

- The Genre I Am WorksheetDocument1 pageThe Genre I Am Worksheetapi-406658477No ratings yet

- 5 Lesson Unit OnDocument9 pages5 Lesson Unit OnAmber KamranNo ratings yet

- Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan Cot1Document4 pagesSemi-Detailed Lesson Plan Cot1Grizel Anne Yutuc OcampoNo ratings yet

- NECO 2020 BECE EXAM TIMETABLEDocument1 pageNECO 2020 BECE EXAM TIMETABLEpaulina ineduNo ratings yet

- 3.1 Exposure Recalling Characteristics of Children in The Different Stages of Cognitive DevelopmentDocument5 pages3.1 Exposure Recalling Characteristics of Children in The Different Stages of Cognitive DevelopmentJohann Emmanuel MolatoNo ratings yet

- International Handbook of Higher EducationDocument1,057 pagesInternational Handbook of Higher EducationTamara Andrea Reyes Pizarro100% (4)

- A Multipotential Life in ArchitectureDocument3 pagesA Multipotential Life in ArchitectureAnthony OrataNo ratings yet

- UPLB Filipiniana Dance Troupe - Banyuhay (Exhibit Materials)Document4 pagesUPLB Filipiniana Dance Troupe - Banyuhay (Exhibit Materials)MarkNo ratings yet

- Federalist Papers Primary Source LessonDocument2 pagesFederalist Papers Primary Source Lessonapi-335575590No ratings yet

- Triple TalaqDocument18 pagesTriple TalaqRaja IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Can reason and perception be separated as ways of knowingDocument2 pagesCan reason and perception be separated as ways of knowingZilvinasGri50% (2)

- Problems Related To Global Media CulturesDocument3 pagesProblems Related To Global Media CulturesJacque Landrito ZurbitoNo ratings yet

- Seth Laws of The Inner Universe LongDocument64 pagesSeth Laws of The Inner Universe LongSakshi Mishra100% (1)

- Old English Language Notes VCEDocument2 pagesOld English Language Notes VCEMy Name is JeffNo ratings yet

- Problems With Parallel StructureDocument9 pagesProblems With Parallel StructureAntin NtinNo ratings yet

- Governing The Female Body - Gender - Health - and Networks of Power PDFDocument323 pagesGoverning The Female Body - Gender - Health - and Networks of Power PDFMarian Siciliano0% (1)

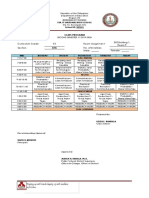

- SHS Schedule (Second Semester)Document24 pagesSHS Schedule (Second Semester)Aziladna SircNo ratings yet

- Creative Nonfiction Q1 M5Document17 pagesCreative Nonfiction Q1 M5Pril Gueta87% (15)

- 2023 Tantra Magic and Vernacular ReligioDocument24 pages2023 Tantra Magic and Vernacular ReligioClaudia Varela ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Family: "A Group of People Who Are Related To Each Other, Such As A Mother, A Father, and Their Children"Document2 pagesFamily: "A Group of People Who Are Related To Each Other, Such As A Mother, A Father, and Their Children"Lucy Cristina ChauNo ratings yet

- Learnenglish ProfessionalsDocument2 pagesLearnenglish ProfessionalsVu Manh CuongNo ratings yet

- Swift Staire On Gullivers TravelDocument5 pagesSwift Staire On Gullivers Travelfarah zaheerNo ratings yet

- Literature and Caste AssignmentDocument4 pagesLiterature and Caste AssignmentAtirek SarkarNo ratings yet

- Management Student Amaan Ali Khan ResumeDocument2 pagesManagement Student Amaan Ali Khan ResumeFalakNo ratings yet

- By: Gorka Alda Josu Echevarria Ruben Vergara Adrian Martinez Adrian Alvarez Social Science 1ºa EsoDocument14 pagesBy: Gorka Alda Josu Echevarria Ruben Vergara Adrian Martinez Adrian Alvarez Social Science 1ºa Esoecheva49No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Template: GCU College of EducationDocument5 pagesLesson Plan Template: GCU College of Educationapi-434634172No ratings yet

- Peaceful Retreat: Designing a Vipassana Meditation Center in Mount AbuDocument14 pagesPeaceful Retreat: Designing a Vipassana Meditation Center in Mount AbuAnonymous Hq7gnMx7No ratings yet

- 3-Methods of PhilosophyDocument9 pages3-Methods of PhilosophyGene Leonard FloresNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Christianity on SocietyDocument4 pagesThe Influence of Christianity on Societyikkiboy21No ratings yet

- Lecture Notes Platos RepublicDocument5 pagesLecture Notes Platos Republicsaurabhsinghspeaks3543No ratings yet

- CcoxxDocument3 pagesCcoxxkeevanyeoNo ratings yet