Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Empress of China, Inaugurating The Ameri

Uploaded by

Rosario Ibañez Gil FloodOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Empress of China, Inaugurating The Ameri

Uploaded by

Rosario Ibañez Gil FloodCopyright:

Available Formats

Asia

S ince the founding of the American repub-

lic, Asia has been a key area of interest

for the United States for both economic and

Asia is a matter of more than just economic

concern, however. Several of the world’s larg-

est militaries are in Asia, including those of

security reasons. One of the first ships to sail China, India, North and South Korea, Paki-

under an American flag was the aptly named stan, Russia, and Vietnam. The United States

Empress of China, inaugurating the Ameri- also maintains a network of treaty alliances

can role in the lucrative China trade in 1784. and security partnerships, as well as a sig-

In the subsequent more than 200 years, the nificant military presence, in Asia. Five Asian

United States has worked under the strategic states (China, North Korea, India, Pakistan,

assumption that it was inimical to American and Russia) possess nuclear weapons.

interests to allow any single nation to domi- The region is a focus of American secu-

nate Asia. Asia constituted too important a rity concerns both because of the presence

market and was too great a source of key re- of substantial military forces and because

sources for the United States to be denied ac- of the legacy of conflict. The two major “hot”

cess. Thus, beginning with U.S. Secretary of wars the United States fought during the Cold

State John Hay’s “Open Door” policy toward War were both in Asia—Korea and Vietnam.

China in the 19th century, the United States Moreover, the Asian security environment

has worked to prevent the rise of a regional is unstable. For one thing, the Cold War has

hegemon, whether it was imperial Japan in not ended in Asia. Of the four states divided

Asia or the Soviet Union in Europe. between Communism and democracy by the

In the 21st century, the importance of Asia Cold War, three (China, Korea, and Vietnam)

to the United States will continue to grow. Al- were in Asia. Neither the Korean nor the Chi-

ready, Asian markets absorb over a quarter of na–Taiwan situation was resolved despite the

American exports in goods and services and, fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the

combined, support one-third of all American Soviet Union.

export-related jobs.1 This number is likely The Cold War itself was an ideological

to grow. conflict layered atop long-standing—and

Not only is Asia still a major market with still lingering—historical animosities. Asia

two of the world’s most populous countries, is home to several major territorial disputes,

but it is also a key source of vital natural re- among them:

sources and such goods as electronic com-

ponents. Over 40 percent of the world’s hard • Northern Territories/Southern Kuriles

drives, for example, are made in Thailand. The (Japan and Russia);

March 2011 earthquake that devastated Japan

had global repercussions as supply chains for • Senkakus/Diaoyutai/Diaoyu Dao (Japan,

a variety of products from cars to computers China, and Taiwan);

were disrupted worldwide.

The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org 129

• Dok-do/Takeshima (Korea and Japan); The Association of Southeast Asian Na-

tions (ASEAN) is a far looser agglomera-

• Paracels/Xisha Islands (Vietnam, China, tion of disparate states, although they have

and Taiwan); succeeded in expanding economic linkages

among themselves over the past 49 years.

• Spratlys/Nansha Islands (China, Tai- Less important to regional stability has been

wan, Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia, and the South Asia Association of Regional Co-

the Philippines); operation (SAARC), which includes Afghani-

stan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives,

• Kashmir (India and Pakistan); and Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. The SAARC

is largely ineffective, both because of the lack

• Aksai Chin and parts of the Indian state of of regional economic integration and because

Arunachal Pradesh (India and China). of the historical rivalry between India and

Pakistan. Also, despite attempts, there is still

Even the various names applied to the dis- no Asia-wide free trade agreement (although

puted territories reflect the fundamental dif- the Trans-Pacific Partnership, if passed, and

ferences in point of view, as each state refers the Regional Comprehensive Economic Part-

to the disputed areas under a different name. nership would help to remedy this gap to

Similarly, different names are applied to the some extent).

various major bodies of water: for example, Similarly, there is no equivalent of NATO,

“East Sea” or “Sea of Japan” and “Yellow Sea” despite an ultimately failed mid-20th cen-

or “West Sea.” tury effort to forge a parallel multilateral se-

These disputes over names also reflect curity architecture through the Southeast

the broader tensions rooted in historical ani- Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). Regional

mosities—enmities that still scar the region. security entities such as the Five Power De-

Most notably, Japan’s actions in World War fence Arrangement (involving the United

II remain a major source of controversy, par- Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia,

ticularly in China and South Korea, where de- and Singapore in an “arrangement,” not an

bates over issues such as what is incorporated alliance) or discussion forums such as the

in textbooks and governmental statements ASEAN Regional Forum and the ASEAN De-

prevent old wounds from completely healing. fense Ministers-Plus Meeting have been far

Similarly, a Chinese claim that much of the weaker. Nor did an Asian equivalent of the

Korean peninsula was once Chinese territory Warsaw Pact arise. Instead, Asian security has

aroused reactions in both Koreas. The end of been marked by a combination of bilateral al-

the Cold War did little to resolve any of these liances, mostly centered on the United States,

underlying disagreements. and individual nations’ efforts to maintain

It is in this light that one should consider their own security.

the lack of a political–security architecture,

or even much of an economic one, undergird- Important Alliances and

ing East Asia. Despite substantial trade and Bilateral Relations in Asia

expanding value chains among the various For the United States, the keys to its po-

Asian states, as well as with the rest of the sition in the Western Pacific are its alliances

world, formal economic integration is lim- with Japan, the Republic of Korea, the Philip-

ited. There is no counterpart to the European pines, Thailand, and Australia. These five alli-

Union or even to the European Economic ances are supplemented by very close security

Community, just as there is no parallel to the relationships with New Zealand, Afghanistan,

European Coal and Steel Community, the Pakistan, and Singapore and evolving rela-

precursor to European economic integration. tionships with other nations in the region like

130 2017 Index of U.S. Military Strength

India, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia. The to engage in collective defensive operations)

U.S. also has a robust unofficial relationship but rejected that policy for itself: Japan would

with Taiwan. employ its forces only in defense of Japan. In

The United States enjoys the benefit of 2015, this changed. The U.S. and Japan revised

sharing common weapons and systems with their defense cooperation guidelines, and the

many of its allies, which facilitates interop- Japanese passed necessary legislation to al-

erability. Many nations, for example, have low Japan to exercise collective self-defense

equipped their infantries with M-16/M-4– in cases involving threats to the U.S. and mul-

based infantry weapons (and share the tilateral peacekeeping operations.

5.56mm caliber); F-15 and F-16 combat air- A similar policy decision was made regard-

craft; and LINK-16 data links. Consequently, ing Japanese arms exports. For a variety of

in the event of conflict, the various air, naval, economic and political reasons, Tokyo has

and even land forces will be capable of sharing chosen to rely on domestic production to

information in such key areas as air defense meet most of its military requirements. At

and maritime domain awareness. This ad- the same time, until very recently, it chose to

vantage is further expanded by the constant limit arms exports, banning them entirely to:

ongoing range of both bilateral and multi-

lateral exercises, which acclimates various • Communist bloc countries;

forces to operating together and familiarizes

both American and local commanders with • Countries that are placed by the U.N.

each other’s standard operating procedures Security Council under arms exports

(SOPs), as well as training and tactics. embargoes; and

Japan. The U.S.–Japan defense relation-

ship is a critical centerpiece in the American • Countries that are involved in or likely to

network of relations in the Western Pacific. be involved in international conflicts.3

The U.S.–Japan Treaty of Mutual Coopera-

tion and Security, signed in 1960, provided The relaxation of these export rules in 2014

for a deep alliance between two of the world’s enabled Japan, among other things, to pursue

largest economies and most sophisticated (ultimately unsuccessfully) an opportunity

military establishments, and changes in Jap- to build new state-of-the-art submarines in

anese defense policies are now enabling an Australia, for Australia, and possible sales of

even greater level of cooperation on security amphibious search and rescue aircraft to the

issues between the two allies and others in Indian navy. Japan has also sold multiple pa-

the region. trol vessels to the Philippine and Vietnamese

Since the end of World War II, Japan’s de- Coast Guards.

fense policy has been distinguished by Article Tokyo relies heavily on the United States

9 of its constitution. This article, which states for its security. In particular, it depends on the

in part that “the Japanese people forever re- United States to deter nuclear attacks on the

nounce war as a sovereign right of the nation home islands. The combination of the pacifist

and the threat or use of force as means of set- constitution and Japan’s past (i.e., the atomic

tling international disputes,”2 in effect pro- bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki) has

hibits the use of force by Japan’s governments forestalled much public interest in obtaining

as an instrument of national policy. It also has an independent nuclear deterrent. Similarly,

led to several other associated policies. throughout the Cold War, Japan relied on the

One such policy is a prohibition on “collec- American conventional and nuclear commit-

tive self-defense.” Japan recognized that na- ment to deter Soviet (and Chinese) aggression.

tions have a right to employ their armed forc- As part of its relationship with Japan,

es to help other states defend themselves (i.e., the United States maintains some 54,000

The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org 131

military personnel and another 8,000 Depart- At least since the 1990 Gulf War, the Unit-

ment of Defense civilian employees in Japan ed States had sought to obtain expanded Jap-

under the rubric of U.S. Forces Japan (USFJ).4 anese participation in international security

These forces include a forward-deployed car- affairs. This effort had generally been resisted

rier battle group (centered on the USS Ronald by Japan’s political system, based on the view

Reagan); a submarine tender; an amphibious that Japan’s constitution, legal decisions, and

assault ship at Yokosuka; and the bulk of the popular attitudes all forbid such a shift. At-

Third Marine Expeditionary Force (III MEF) tempts to expand Japan’s range of defense ac-

on Okinawa. U.S. forces exercise regularly tivities, especially away from the home islands,

with their Japanese counterparts; in recent have often been met by vehement opposition

years, this collaboration has expanded from from Japan’s neighbors, especially China and

air and naval exercises to practicing amphibi- South Korea, due to unresolved differences

ous operations together. on issues ranging from territorial claims and

Supporting the American presence is a boundaries to historical grievances and Japa-

substantial American defense infrastructure nese visits to the Yasukuni Shrine. Even with

established throughout Japan, including the changes, these issues will doubtless con-

Okinawa. The array of major bases provides tinue to constrain Japan’s contributions to

key logistical and communications support the alliance.

for U.S. operations throughout the West- These issues have been sufficient to tor-

ern Pacific, cutting travel time substantially pedo efforts to improve defense cooperation

compared with deployments from Hawaii or between Seoul and Tokyo, a fact highlighted

the American West Coast. They also provide in 2012 by South Korea’s last-minute deci-

key listening posts on Russian, Chinese, and sion not to sign an agreement to share sensi-

North Korean military operations. This is tive military data, including details about the

likely to be supplemented by Japan’s growing North Korean threat to both countries.7 In

array of space systems, including new recon- December 2014, the U.S., South Korea, and Ja-

naissance satellites. pan signed a minimalist military data-sharing

The Japanese government defrays a sub- agreement limited only to information on the

stantial portion of the cost of the American North Korean military threat and requiring

presence. At present, the government of Ja- both allies to pass information through the

pan provides some $2 billion annually to United States military. Similar controversies,

support the cost of USFJ.5 These funds cover rooted in history as well as in contemporary

a variety of expenses, including utility and la- politics, have also affected Sino–Japanese re-

bor costs at U.S. bases, improvements to U.S. lations and, to a lesser extent, Japanese ties to

facilities in Japan, and the cost of relocating some Southeast Asian states.

training exercises away from populated areas Nonetheless, Prime Minister Shinzō Abe

in Japan. has pushed through a reinterpretation of the

U.S.–Japanese defense cooperation is un- legality of Japanese participation in “collective

dergirded not only by the mutual security self-defense” situations, as well as a loosening

treaty, but also by the new 2015 U.S.–Japan of restrictions on arms sales. The combination

Defense Guidelines. The guidelines allow of reforms provides the legal foundation for

both the geographic scope and the nature of much greater Japanese interaction with other

Japan’s security contributions to include op- states in defense arenas, including joint pro-

erations “involving the use of force to respond duction of weapons and components and the

to situations where an armed attack against a potential for interaction with foreign military

foreign country that is in a close relationship forces.8

with Japan occurs.”6 The revisions make Ja- Republic of Korea. The United States

pan a fuller partner in the alliance. and the Republic of Korea (ROK) signed the

132 2017 Index of U.S. Military Strength

Mutual Defense Treaty in 1953. That treaty forces located on the peninsula). In 2003,

codified the relationship that had grown from South Korean president Roh Moo-hyun, as

the Korean War, when the United States dis- agreed with the U.S., began the process of

patched troops to help South Korea defend transferring wartime operational control

itself against invasion by Communist North from CFC to South Korean commanders,

Korea. Since then, the two states have forged thereby establishing the ROK military as fully

an enduring alliance that supplements a sub- independent of the United States. This deci-

stantial trade and economic relationship that sion engendered significant opposition with-

includes a free trade agreement. in South Korea, however, and raised serious

The United States currently maintains military questions about the impact on unity

some 28,500 troops in Korea, the largest con- of command. Coupled with various North Ko-

centration of American forces on the Asian rean provocations (including a spate of mis-

mainland. This is centered mainly on the U.S. sile tests as well as attacks on South Korean

2nd Infantry Division and a significant num- military forces and territory in 2010), Wash-

ber of combat aircraft. ington and Seoul agreed in late 2014 to post-

The U.S.–ROK defense relationship in- pone wartime OPCON transfer.9

volves one of the more integrated and com- The domestic political constraints under

plex command-and-control structures. A which South Korea’s military operates are

United Nations Command (UNC) established less stringent than those that govern the op-

in 1950 was the basis for the American inter- erations of the Japanese military. Thus, South

vention, and it remained in place after the Korea rotated several divisions to fight along-

armistice was signed in 1953. UNC has access side Americans in Vietnam. In the first Gulf

to a number of bases in Japan in order to sup- War, the Iraq War, and Afghanistan, South

port U.N. forces in Korea. In concrete terms, Korea limited its contributions to non-com-

however, it only oversaw South Korean and batant forces and monetary aid. The focus of

American forces as other nations’ contribu- South Korean defense planning remains on

tions were gradually withdrawn or reduced to North Korea, however, especially as Pyong-

token elements. yang has deployed its forces in ways that op-

In 1978, operational control of frontline timize a southward advance. Concerns about

South Korean and American military forces North Korea have been heightened in recent

transitioned from UNC to Combined Forces years in the wake of the sinking of the South

Command (CFC). Headed by an American of- Korean frigate Cheonan and the shelling of

ficer (who is also the Commander, U.N. Com- Yongpyeong-do, perhaps the most serious in-

mand), CFC reflects an unparalleled degree cident in decades. Moreover, in the past sev-

of U.S.–South Korean military integration. eral conflicts (e.g., Operation Iraqi Freedom),

Similarly, the system of Korean Augmentees Seoul has not provided combat forces, prefer-

to the United States Army (KATUSA), which ring instead to send humanitarian and non-

places South Korean soldiers into American combatant assistance.

units assigned to Korea, allows for a degree Over the past several decades, the Ameri-

of tactical-level integration and cooperation can presence on the peninsula has slowly de-

that is atypical. clined. In the early 1970s, President Richard

Current command arrangements for the Nixon withdrew the 7th Infantry Division,

U.S. and ROK militaries are for CFC to ex- leaving only the 2nd Infantry Division on the

ercise operational control (OPCON) of all peninsula. Those forces have been positioned

forces on the peninsula in time of war, while farther back so that there are few Americans

peacetime control rests with respective na- deployed on the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).

tional authorities (although the U.S. exercises Washington has agreed to maintain 28,500

peacetime OPCON over non-U.S., non-ROK troops in the ROK. These forces regularly

The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org 133

engage in major exercises with their ROK colonial era. In 1991, a successor to the Mili-

counterparts, including the Key Resolve and tary Bases Agreement between the U.S. and

Foal Eagle series. Both of these series involve the Philippines was submitted to the Philip-

the actual deployment of a substantial num- pine Senate for ratification. The Philippines,

ber of forces and are partly intended to deter after a lengthy debate, rejected the treaty,

Pyongyang, as well as to give U.S. and ROK compelling American withdrawal from Phil-

forces a chance to practice operating together. ippine bases. Coupled with the effects of the

The ROK government also provides sub- 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo (which dev-

stantial resources to defray the costs of U.S. astated Clark Air Base and damaged many

Forces–Korea. It provides some $900 million Subic Bay facilities) and the end of the Cold

annually in either direct funding or in-kind War, closure of the bases was not seen as fun-

support, covering cost-sharing for labor, lo- damentally damaging to America’s posture in

gistics, and improvements in facilities.10 the region.

The Philippines. America’s oldest de- Moreover, despite the closing of the Amer-

fense relationship in Asia is with the Philip- ican bases and consequent slashing of Ameri-

pines. The United States seized the Philip- can military assistance, U.S.–Philippine mili-

pines from the Spanish over a century ago as tary relations remained close, and assistance

a result of the Spanish–American War and a began to increase again after 9/11 as U.S. forces

subsequent conflict with Philippine indige- assisted the Philippines in countering Islamic

nous forces. But the U.S., unlike other colonial terrorist groups, including Abu Sayyaf, in the

states, also put in place a mechanism for the south of the archipelago. From 2002–2015,

Philippines to gain its independence, transi- the U.S. rotated 500–600 special operations

tioning through a period as a commonwealth forces regularly through the Philippines to as-

until the archipelago was granted indepen- sist in counterterrorism operations. That op-

dence in 1946. Just as important, substantial eration, Joint Special Operations Task Force-

numbers of Filipinos fought alongside the Philippines (JSOTF-P), closed in the first part

United States against Japan in World War II, of 2015, but the U.S. presence in Mindanao

establishing a bond between the two peoples. continues at reduced levels. Another 6,000

Following World War II and after assisting participate in combined exercises with Phil-

the newly independent Filipino government ippine troops.11

against the Communist Hukbalahap move- In 2014, the United States and the Philip-

ment in the 1940s, the United States and the pines announced a new Enhanced Defense

Philippines signed a mutual security treaty. Cooperation Agreement (EDCA), which al-

For much of the period between 1898 and lows for an expanded American presence

the end of the Cold War, the largest Ameri- in the archipelago,12 and in early 2016, they

can bases in the Pacific were in the Philip- agreed on five specific bases subject to the

pines, centered around the U.S. Navy base in agreement. Under the EDCA, U.S. forces will

Subic Bay and the complex of airfields that rotate through these locations on an expand-

developed around Clark Field (later Clark ed basis, allowing for a more regular presence

Air Base). While the Philippines have never (but not new, permanent bases) in the islands,

had the ability to provide substantial finan- and will engage in more joint training with

cial support for the American presence, the AFP forces. The agreement also facilitates the

base infrastructure was unparalleled, provid- provision of humanitarian assistance and di-

ing replenishment and repair facilities and saster relief (HA/DR). The United States also

substantially extending deployment periods agreed to improve the facilities it uses and to

throughout the East Asian littoral. transfer and sell more military equipment to

These bases were often centers of contro- the AFP to help it modernize. This is an im-

versy, however, as they were reminders of the portant step, as the Philippine military has

134 2017 Index of U.S. Military Strength

long been one of the weakest in the region, U.S. and Thai forces regularly exercise

despite the need to defend an incredibly large together, most notably in the annual Cobra

expanse of ocean, shoreline, and territory. Gold exercises, first begun in 1982. This builds

One long-standing difference between the on a partnership that began with the dispatch

U.S. and the Philippines has been the applica- of Thai forces to the Korean War, where over

tion of the U.S.–Philippine Mutual Defense 1,200 Thai troops died (out of some 6,000

Treaty to disputed islands in the South China deployed). The Cobra Gold exercises are

Sea. While the U.S. has long maintained that among the world’s largest multilateral mili-

the treaty does not extend American obliga- tary exercises.

tions to disputed areas and territories, Fili- U.S.–Thai relations have been strained in

pino officials occasionally have held other- recent years as a result of domestic unrest

wise.13 The EDCA does not settle this question, and two coups in Thailand. This strife has

but the growing tensions in the South China limited the extent of U.S.–Thai military coop-

Sea, including in recent years at Scarborough eration, as U.S. law prohibits U.S. funding for

Shoal, have highlighted Manila’s need for many kinds of assistance to a foreign coun-

greater support from and cooperation with try in which a military coup deposes a duly

Washington. Moreover, the U.S. government elected head of government. Nonetheless,

has long been explicit that any attack on Phil- the two states continue to cooperate, includ-

ippine government ships or aircraft, or on the ing in joint military exercises and in the area

Philippine armed forces, would be covered of counterterrorism. The Counter Terrorism

under the Treaty, “thus separating the issue Information Center (CTIC) continues to al-

of territorial sovereignty from attack on Phil- low the two states to share vital information

ippine military and public vessels.”14 about terrorist activities in Asia. CTIC is al-

In 2016, the Philippines elected a new, very leged to have played a key role in the capture

unconventional President, Rodrigo Duterte, of the leader of Jemaah Islamiyah, Hambali,

to a six-year term. His rhetorical challenges in 2003.15

to current priorities in the U.S.–Philippines Thailand has also been drawing closer to

alliance raise questions about the trajectory the People’s Republic of China (PRC). This

of the alliance and the sustainability of new process has been underway since the end of

initiatives that are important to it. the Vietnam War but is accelerating due to ex-

Thailand. The U.S.–Thai security rela- panding economic relations between the two

tionship is built on the 1954 Manila Pact, states. Between 2005 and 2010, the value of

which established the now-defunct South- trade between the two states doubled. Today,

east Asia Treaty Organization, and the 1962 China is Thailand’s leading trading partner.16

Thanat–Rusk agreement. These were supple- The Thai and Chinese militaries also

mented by the 2012 Joint Vision statement have improved relations over the years. In-

for U.S.–Thai relations. In 2003, Thailand was telligence officers began formal meetings in

designated a “major, non-NATO ally,” giving it 1988. Thai and Chinese military forces have

improved access to American arms sales. engaged in joint counterterrorism exercises

Thailand’s central location has made it an since 2007, and the two nations’ marines have

important component of the network of U.S. exercised jointly since 2010.17 Thai–Chinese

alliances in Asia. During the Vietnam War, a va- military relations may have accelerated as a

riety of American aircraft were based in Thai- result of the U.S. restrictions imposed in the

land, ranging from fighter-bombers and B-52s wake of Thai political instability.

to reconnaissance aircraft. In the first Gulf War Australia. Australia is one of the most

and again in the Iraq War, some of those same important American allies in the Asia–Pa-

air bases were essential for the rapid deploy- cific. U.S.–Australia security ties date back to

ment of American forces to the Persian Gulf. World War I, when U.S. forces fought under

The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org 135

Australian command on the Western Front. allow for the expedited and simplified export

These ties deepened during World War II or transfer of certain defense services and

when, after Japan commenced hostilities in items between the U.S. and its two key part-

the Western Pacific, Australian forces com- ners without the need for export licenses or

mitted to the North Africa campaign were not other approvals under the International Traf-

returned to defend the continent—despite fic in Arms Regulations. This also allows for

British promises to do so. As Japanese forces much greater integration among the Ameri-

attacked the East Indies and secured Singa- can, Australian, and British defense industrial

pore, Australia turned to the United States to establishments.23

bolster its defenses, and American and Aus- Singapore. Although Singapore is not a

tralian forces subsequently cooperated close- security treaty ally of the United States, it is

ly in the Pacific War. Those ties and America’s a key security partner in the region. In 2005,

role as the main external supporter for Aus- the close defense relationship was formalized

tralian security were codified in the Australia– with the Strategic Framework Agreement

New Zealand–U.S. (ANZUS) pact of 1951. (SFA), and in 2015, it was expanded with the

A key part of the Obama Administration’s U.S.–Singapore Defense Cooperation Agree-

“Asia pivot” was to rotate additional United ment (DCA).

States Air Force units and Marines through The 2005 SFA was the first agreement of its

Northern Australia.18 Eventually expected kind since the end of the Cold War. 24 It built

to total some 2,500 troops, the initial con- on the 1990 Memorandum of Understand-

tingents of Marine forces are based near the ing Regarding United States Use of Facilities

northern city of Darwin. The two sides con- in Singapore, as amended, which allows for

tinue to negotiate the terms of the full de- U.S. access to Singaporean military facili-

ployment, which it is now estimated will be ties.25 The 2015 DCA establishes “high-level

complete by 2020.19 Meanwhile, the two na- dialogues between the countries’ defense es-

tions engage in a variety of security coopera- tablishments” and a “broad framework for de-

tion efforts, including joint space surveillance fense cooperation in five key areas, namely in

activities. These were codified in 2014 with the military, policy, strategic and technology

an agreement that allows sharing of space in- spheres, as well as cooperation against non-

formation data among the U.S., Australia, the conventional security challenges, such as pi-

U.K., and Canada.20 racy and transnational terrorism.”26

The two nations’ chief defense and foreign New Zealand. For much of the Cold War,

policy officials meet annually in the Austra- U.S. defense ties with New Zealand were simi-

lia–United States Ministerial (AUSMIN) pro- lar to those between America and Australia.

cess to address such issues of mutual concern As a result of controversies over U.S. Navy

as security developments in the Asia–Pacific employment of nuclear power and the pos-

region, global security and development con- sibility of deployment of U.S. naval vessels

cerns, and bilateral security cooperation.21 with nuclear weapons, the U.S. suspend its

Australia has also granted the United States obligations to New Zealand under the 1951

access to a number of joint facilities, includ- ANZUS Treaty. Defense relations improved,

ing space surveillance facilities at Pine Gap however, in the early 21st century as New

and naval communications facilities on the Zealand committed forces to Afghanistan

North West Cape of Australia.22 and also dispatched an engineering detach-

Australia and the United Kingdom are two ment to Iraq. The 2010 Wellington Declara-

of America’s closest partners in the defense tion and the 2012 Washington Declaration,

industrial sector. In 2010, the United States while not restoring full security ties, allowed

approved Defense Trade Cooperation Trea- the two nations to resume high-level defense

ties with Australia and the U.K. These treaties dialogues. In 2013, U.S. Secretary of Defense

136 2017 Index of U.S. Military Strength

Chuck Hagel and New Zealand Defense Min- resort to force or other forms of coercion that

ister Jonathan Coleman announced the re- would jeopardize the security, or the social or

sumption of military-to-military coopera- economic system, of the people on Taiwan.”30

tion,27 and in July 2016, the U.S. accepted an The TRA requires the President to inform

invitation from New Zealand to make a single Congress promptly of “any threat to the secu-

port call, reportedly with no change in U.S. rity or the social or economic system of the

policy to confirm or deny the presence of nu- people on Taiwan and any danger to the inter-

clear weapons on board.28 This may portend a ests of the United States arising therefrom.”

longer-term solution to the nuclear impasse The TRA then states: “The President and

between the two nations. the Congress shall determine, in accordance

Taiwan. When the United States shifted with constitutional processes, appropriate

its recognition of the government of China action by the United States in response to any

from the Republic of China (on Taiwan) to the such danger.”

People’s Republic of China (the mainland), it Supplementing the TRA are the “Six As-

declared certain commitments concerning surances” issued by President Ronald Rea-

the security of Taiwan. These commitments gan in a secret July 1982 memo, subsequently

are embodied in the Taiwan Relations Act publicly released and the subject of a Senate

(TRA) and the subsequent “Six Assurances.” hearing. These six assurances were intended

The TRA is an American law and not a to moderate the third Sino–American com-

treaty. Under the TRA, the United States munique, itself generally seen as one of the

maintains programs, transactions, and other “Three Communiques” that form the founda-

relations with Taiwan through the American tion of U.S.–PRC relations. These assurances

Institute in Taiwan (AIT). Except for the U.S.– of July 14, 1982, were as follows:

China Mutual Defense Treaty, which had gov-

erned U.S. security relations with Taiwan, all 1. In negotiating the third Joint Communi-

other treaties and international agreements que with the PRC, the United States:

made between the Republic of China and the

United States remain in force. (The Sino–U.S. 2. has not agreed to set a date for ending

Mutual Defense Treaty was terminated by arms sales to Taiwan;

President Jimmy Carter following the shift in

recognition to the PRC.) 3. has not agreed to hold prior consultations

Under the TRA, it is the policy of the Unit- with the PRC on arms sales to Taiwan;

ed States “to provide Taiwan with arms of a

defensive character.” The TRA also states that 4. will not play any mediation role between

the U.S. will “make available to Taiwan such Taipei and Beijing;

defense articles and services in such quan-

tity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to 5. has not agreed to revise the Taiwan Rela-

maintain a sufficient self-defense capability.” tions Act;

The U.S. has implemented these provisions of

the TRA through sales of weapons to Taiwan. 6. has not altered its position regarding sov-

The TRA states that it is U.S. policy to ereignty over Taiwan;

“consider any effort to determine the future of

Taiwan by other than peaceful means, includ- 7. will not exert pressure on Taiwan to nego-

ing by boycotts or embargoes, a threat to the tiate with the PRC.31

peace and security of the Western Pacific area

and of grave concern to the United States.”29 Although the United States sells Taiwan a

It also states that it is U.S. policy to “maintain variety of military equipment, it does not en-

the capacity of the United States to resist any gage in joint exercises with the Taiwan armed

The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org 137

forces. Some Taiwan military officers, how- Medical Storage Initiative (CHAMSI), which

ever, do receive training in the United States, will advance cooperation on humanitarian

attending American professional military assistance and disaster relief by, among oth-

education institutions. There also are regular er things, prepositioning related American

high-level meetings between senior U.S. and equipment in Danang, Vietnam.32

Taiwan defense officials, both uniformed and There remain significant limits on the U.S.–

civilian. The United States does not maintain Vietnam security relationship, including a

any bases in Taiwan or its territories. Vietnamese defense establishment that is very

Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia. The cautious in its selection of defense partners,

U.S. has security relationships with several key party-to-party ties between the Communist

Southeast Asian countries, none of them as parties of Vietnam and China, and a foreign

extensive and formal as its relationship with policy that seeks to balance relationships with

Singapore and its treaty allies but all still of all major powers. The U.S. remains, like oth-

growing significance. The U.S. “rebalance” to ers among Vietnam’s security partners, offi-

the Pacific has incorporated a policy of “rebal- cially limited to one port call a year and has not

ance within the rebalance” that has included docked a warship at Cam Ranh Bay since the

efforts to expand relations with this second end of the Vietnam War. This may change with

tier of American security partners. the inauguration of a new international port

Since shortly after the normalization of there this year,33 but the benefits of that access

diplomatic relations between the two coun- will be shared among all capable Vietnamese

tries in 1995, the U.S. and Vietnam also have partners, not just the U.S. Navy.

normalized their defense relationship, albeit The U.S. and Malaysia have maintained

very slowly. The relationship was codified in a “steady level” of defense cooperation since

2011 with a Memorandum of Understand- the 1990s, despite occasional political differ-

ing “advancing bilateral defense cooperation” ences. Each year, they now participate jointly

that covers five areas of operations, including in dozens of bilateral and multilateral exer-

maritime security. The most significant de- cises to promote effective cooperation across

velopment in security ties over the past sev- a range of missions.34 The U.S. has specifically

eral years has been the relaxation of the ban discussed with Malaysia arrangements for

on sales of arms to Vietnam. In the fall of 2014, rotating maritime patrol aircraft through Ma-

the U.S. lifted the embargo on maritime secu- laysian bases in Borneo.

rity–related equipment, and then on President The U.S.–Indonesia defense relationship

Barack Obama’s visit to Hanoi in 2016, it lifted revived in 2005 following a period of estrange-

the ban completely. This full embargo had long ment over American human rights concerns.

served as a psychological obstacle to Vietnam- It now includes regular joint exercises, port

ese cooperation on security issues. Lifting it calls, and sale of weaponry. The U.S. is also

does not necessarily change the nature of the working closely with Indonesia’s defense es-

articles likely to be sold, and no transfers, in- tablishment to institute reforms in Indone-

cluding P-3 maritime patrol aircraft, discussed sia’s strategic defense planning processes.

since the relaxation of the embargo two years The U.S. is working across the board at

ago, have been made. Lifting the embargo does, modest levels of investment to help build

however, expand the potential of the relation- Southeast Asia’s maritime security capacity.35

ship and better positions the U.S. to compete Most notable in this regard is the Maritime

with Chinese and Russian positions there. Security Initiative (MSI) announced by Sec-

The Joint Statement from President Obama’s retary of Defense Ashton Carter in 2015.36

visit also memorialized a number of other im- Afghanistan. On October 7, 2001, U.S.

provements in the U.S.–Vietnam relationship, forces invaded Afghanistan in response to

including the Cooperative Humanitarian and the September 11, 2001, attacks on the United

138 2017 Index of U.S. Military Strength

States, marking the beginning of Operation routes from the port at Karachi to Afghan–

Enduring Freedom to combat al-Qaeda and Pakistani border crossing points at Torkham

its Taliban supporters. The U.S., in alliance in the Khyber Pass and Chaman in Baluch-

with the U.K. and the anti-Taliban Afghan istan province. During the initial years of

Northern Alliance forces, ousted the Taliban the Afghan war, about 80 percent of U.S. and

from power in December 2001. Most Taliban NATO supplies traveled through Pakistani

and al-Qaeda leaders fled across the border territory. This amount decreased to around

into Pakistan’s Federally Administered Trib- 50 percent–60 percent as the U.S. shifted to

al Areas (FATA), where they regrouped and northern routes and when U.S.–Pakistan re-

started an insurgency in Afghanistan in 2003. lations significantly deteriorated over U.S.

In August 2003, NATO joined the war in drone strikes, continued Pakistani support to

Afghanistan and assumed control of the In- Taliban militants, and the fallout surrounding

ternational Security Assistance Force (ISAF). the U.S. raid on Osama bin Laden’s hideout in

At the height of the war in 2011, there were Abbottabad on May 2, 2011.

50 troop-contributing nations and a total of From October 2001 until December 2011,

nearly 150,000 NATO and U.S. forces on the the U.S. leased Pakistan’s Shamsi airfield

ground in Afghanistan. southwest of Quetta in Pakistan’s Baluchistan

On December 28, 2014, NATO formally province and used it as a base from which to

ended combat operations and handed re- conduct surveillance and drone operations

sponsibility to the Afghan security forces, against terrorist targets in Pakistan’s tribal

currently numbering around 326,000 (in- border areas. Pakistan ordered the U.S. to

cluding army and police).37 After Afghan vacate the base shortly after NATO forces at-

President Ashraf Ghani signed a bilateral se- tacked Pakistani positions along the Afghani-

curity agreement with the U.S. and a Status of stan border, killing 24 Pakistani soldiers, on

Forces Agreement with NATO, the interna- November 26, 2011.

tional coalition launched Operation Resolute Escalation of the U.S. drone strike cam-

Support to train and support Afghan security paign in Pakistan’s border areas from 2009–

forces. As of June 2016, approximately 13,200 2012 led to the significant degradation of

U.S. and NATO forces were stationed in Af- al-Qaeda’s ability to plot, plan, and train for

ghanistan. Most U.S. and NATO forces are terrorist attacks. The U.S. began to curtail

stationed at bases in Kabul and Bagram, with drone strikes in 2013, largely as a result of

tactical advise-and-assist teams located in Pakistan’s growing complaints that the drone

Mazar-i-Sharif, Herat, Kandahar, Jalalabad, campaign infringed on its sovereignty and

and Gamberi. criticism from international human rights

In 2014, President Obama pledged to cut organizations about the number of civilian

U.S. force levels to around 5,500 by the end of casualties resulting from the attacks. All told,

2015 and then to zero by the end of 2016, but there have been over 400 drone strikes since

he reversed himself last fall, announcing that January 2008, including the strike that killed

the U.S. instead would maintain this force Taliban leader Mullah Akhtar Mansour in

level when he departs office. He revised plans Baluchistan province in May 2016.

again in 2016 to say that he would keep 8,400 The U.S. provides significant amounts

in place, leaving any further reductions up to of military aid to Pakistan and “reimburse-

his successor. ments” in the form of coalition support funds

Pakistan. During the war in Afghanistan, (CSF) for Pakistan’s military deployments

the U.S. and NATO relied heavily on logisti- and operations along the border with Af-

cal supply lines running through Pakistan to ghanistan. Pakistan has some 150,000 troops

resupply coalition forces in Afghanistan. Sup- stationed in regions bordering Afghanistan

plies and fuel were carried on transportation and recently conducted a robust military

The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org 139

campaign against Pakistani militants in January 2015 visit to India, the two sides

North Waziristan. Since FY 2002, the U.S. has agreed to renew and upgrade their 10-year

provided almost $8 billion in security-related Defense Framework Agreement. Under the

assistance and more than $14 billion in CSF Defense Trade and Technology Initiative

funds to Pakistan.38 While $1 billion in CSF (DTTI) launched in 2012, the U.S. and India

reimbursements was authorized for Pakistan are cooperating on development of six very

in 2015, the U.S. withheld $300 million of this specific “pathfinder” technology projects.39

funding because of Pakistan’s failure to crack During Prime Minister Modi’s visit to the

down on the Haqqani network. Reflecting a U.S. in June 2016, the two sides welcomed

trend of growing congressional resistance to finalization of the text of a logistics-sharing

military assistance for Pakistan, in 2016, Con- agreement that would allow each country to

gress blocked funds for the provision of eight access the other’s military supplies and refu-

F-16s to Pakistan. eling capabilities through ports and military

India. During the Cold War, U.S.–Indian bases. The signing of the logistics agreement,

military cooperation was minimal, except for formally called the Logistics Exchange Mem-

a brief period during the Sino–Indian border orandum of Agreement (LEMOA), marks a

war in 1962 when the U.S. sided with India milestone in the Indo–U.S. defense partner-

and supplied it with arms and ammunition. ship. New Delhi and Washington regularly

The rapprochement was short-lived, however, hold joint exercises across all services, in-

and mutual suspicion continued to mark the cluding an annual naval exercise in which Ja-

Indo–U.S. relationship due to India’s robust pan will now participate on an annual basis

relationship with Russia and the U.S. provi- and in which Australia and Singapore have

sion of military aid to Pakistan, especially also participated in the past.

during the 1970s under the Nixon Adminis-

tration. America’s ties with India hit a nadir Quality of Allied Armed Forces in Asia

during the 1971 Indo–Pakistani war when the Because of the lack of an integrated, re-

U.S. deployed the aircraft carrier USS Enter- gional security architecture along the lines of

prise toward the Bay of Bengal in a show of NATO, the United States partners with most

support for Pakistani forces. of the nations in the region on a bilateral basis.

Military ties between the U.S. and India This means that there is no single standard to

have improved significantly over the past de- which all of the local militaries aspire; instead,

cade as the two sides have moved toward es- there is a wide range of capabilities that are

tablishment of a strategic partnership based influenced by local threat perceptions, insti-

on their mutual concern over rising Chinese tutional interests, physical conditions, his-

military and economic influence and converg- torical factors, and budgetary considerations.

ing interests in countering regional terrorism. Moreover, the lack of recent major conflicts

The U.S. and India have completed contracts in the region makes assessing the quality of

worth nearly $14 billion for the supply of U.S. Asian armed forces difficult. Most Asian mili-

military equipment to India, including C-130J taries have limited combat experience; some

and C-17 transport aircraft and P-8 maritime (e.g., Malaysia) have never fought an exter-

surveillance aircraft. nal war since gaining independence in the

Defense ties between the two countries mid-20th century. The Indochina wars, the

are poised to expand further as India moves most recent high-intensity conflicts, are now

forward with an ambitious military mod- 30 years in the past. It is therefore unclear

ernization program and following three how well Asian militaries have trained for fu-

successful summit-level meetings between ture warfare and whether their doctrine will

President Obama and Indian Prime Minister meet the exigencies of wartime realities. In

Narendra Modi. During President Obama’s particular, no Asian militaries have engaged

140 2017 Index of U.S. Military Strength

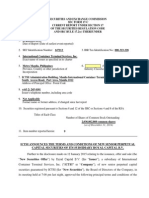

MAP 3

The Tyranny of Distance

Steam times are in

parentheses. Arctic

Ocean

RUSSIA Alaska

Gulf of

Bering Alaska U.S.

Sea

San Diego

40°N 6,700 miles

CHINA JAPAN (13–21 days)

160°

140

Tokyo

°W

W

180°

1,700 miles

160°E

Okinawa

1,000 miles (2–3 days)

South 20°N

Hawaii

China

Sea 5,000 miles

(10–16 days)

Guam

1,700 miles

(3–5 days)

Pa

c i fi 0°

c Oc

ean

1,900 miles Darwin

20°S

AUSTRALIA

SOURCE: Heritage Foundation estimates based on data from Shirley A. Kan, “Guam: U.S. Defense Deployments,”

Congressional Research Service, April 29, 2014, Table 1, https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=752725 (accessed January 13, 2015).

heritage.org

in high-intensity air or naval combat, so the Korea’s, and Australia’s defense budgets are

quality of their personnel, training, or equip- estimated to be among the 15 largest in the

ment is likewise unclear. world. Each of their military forces fields

Based on examinations of equipment, how- some of the world’s most advanced weapons,

ever, it is assessed that several Asian allies and including F-15s in the Japan Air Self Defense

friends have substantial military capabilities Force and ROK Air Force; airborne early warn-

supported by robust defense industries and ing (AEW) platforms; AEGIS-capable sur-

significant defense spending. Japan’s, South face combatants and modern diesel-electric

The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org 141

submarines; and third-generation main bat- while relying on the United States for its ex-

tle tanks. All three nations are currently com- ternal security, the AFP has one of the lowest

mitted to purchasing F-35 fighters. budgets in the region—and one of the most

At this point, both the Japanese and Kore- extensive coastlines to defend. With a defense

an militaries are arguably more capable than budget of only $2.5 billion and confronted

most European militaries, at least in terms with a number of insurgencies, including the

of conventional forces. Japan’s Self Defense Islamist Abu Sayyaf and New People’s Army,

Forces, for example, field more tanks, princi- Philippine defense resources have long been

pal surface combatants, and fighter/ground stretched thin. The last squadron of fighter

attack aircraft (777, 47, and 340, respective- aircraft (1960s-vintage F-5 fighters) was re-

ly) than their British opposite numbers (227, tired several years ago; the Philippine Air

18, and 230, respectively).40 Similarly, South Force (PAF) has had to employ its S-211 train-

Korea fields a larger military of tanks, prin- ers as fighters and ground attack aircraft. The

cipal surface combatants, submarines, and most modern ships in the Philippine navy are

fighter/ground attack aircraft (more than two former U.S. Hamilton-class Coast Guard

1,000, 28, 23, and 468, respectively) than their cutters; its other main combatant is a World

German counterparts (322, 19, four, and 209, War II destroyer escort, one of the world’s old-

respectively).41 est serving warships.

Both the ROK and Japan are also increas-

ingly interested in developing missile defense Current U.S. Presence in Asia

capabilities. Although South Korea and the The U.S. Pacific Command (PACOM) is the

United States agreed in 2016 (after much oldest and largest of American unified com-

negotiation and indecision) to deploy Amer- mands. Established on January 1, 1947, PA-

ica’s Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense COM, “together with other U.S. government

(THAAD) missile defense system on the pen- agencies, protects and defends the United

insula, South Korea also continues to pursue States, its territories, allies, and interests”42

an indigenous missile defense capability. To this end, the U.S. seeks to preserve a “geo-

Singapore’s small population and physical graphically distributed, operationally resil-

borders limit the size of its military and there- ient, and politically sustainable” regional

fore its defense budget, but in terms of equip- force posture within the PACOM area of re-

ment and training, it nonetheless fields some sponsibility that can effectively deter any po-

of the highest-quality forces in the region. For tential adversaries.43

example, Singapore’s ground forces can de- PACOM’s area of responsibility includes

ploy third-generation Leopard II main battle not only the expanses of the Pacific, but also

tanks; its fleet includes five conventional sub- Alaska and portions of the Arctic, South Asia,

marines (including one with air-independent and the Indian Ocean. It includes 36 nations

propulsion systems), six frigates, and six holding more than 50 percent of the world’s

missile-armed corvettes; and the Singapore population, two of the three largest econo-

air force not only has F-15E Strike Eagles and mies, and nine of the 10 smallest; the most

F-16s, but also has one of Southeast Asia’s larg- populous nation (China); the largest democ-

est fleets of airborne early warning and control racy (India); the largest Muslim-majority na-

aircraft (six G550 aircraft) and a tanker fleet tion (Indonesia); and the world’s smallest re-

of KC-130s that can help extend range or time public (Nauru). The region is a vital driver of

on station. the global economy and includes the world’s

At the other extreme, the Armed Forces of busiest international sea-lanes and nine of its

the Philippines (AFP) are among the region’s 10 largest ports. By any meaningful measure,

weakest military forces. Having long focused the Asia–Pacific is also the most militarized

on waging counterinsurgency campaigns region in the world, with seven of its 10 largest

142 2017 Index of U.S. Military Strength

standing militaries and five of its declared nu- the western border of Third Fleet’s AOR47

clear nations.44 to involve its five carrier strike groups48

Under PACOM are a number of compo- more routinely in the Western Pacific.

nent commands, including:

Since the announcement of the “Asia pivot,”

• U.S. Army Pacific. USARPAC is the it has been reported that the United States

Army’s component command in the will shift more Navy and Air Force assets

Pacific. It is comprised of 80,000 soldiers to the Pacific. It is expected that eventu-

and supplies Army forces as necessary ally, some 60 percent of U.S. Navy assets

for various global contingencies. Among will be deployed to the Pacific (although it

others, it administers the 25th Infantry remains unclear whether they will be per-

Division headquartered in Hawaii, the U.S. manently based there). That percentage,

Army Japan, and U.S. Army Alaska.45 however, will be drawn from a fleet that is

shrinking in overall size, so the net effect

• U.S. Pacific Air Force. PACAF is re- may actually be fewer forces deployed than

sponsible for planning and conducting before. Over the past year, the conduct

defensive and offensive air operations of Freedom of Navigations Operations

in the Asia–Pacific region. It has three (FONOPS) that challenge excessive mari-

numbered air forces under its command: time claims, a part of the Navy’s mission

5th Air Force (in Japan); 7th Air Force (in since 1979, has assumed a very high profile

Korea); and 11th Air Force (headquartered as a result of three well-publicized opera-

in Alaska). These field two squadrons of tions in the South China Sea.

F-15s, two squadrons of F-22s, five squad-

rons of F-16s, and a single squadron of • U.S. Marine Forces Pacific. MARFOR-

A-10 ground attack aircraft, as well as two PAC controls elements of the U.S. Marine

squadrons of E-3 early-warning aircraft, Corps operating in the Asia–Pacific region.

tankers, and transports.46 Other forces Its headquarters are in Hawaii. Because of

that regularly come under PACAF com- its extensive responsibilities and physical

mand include B-52, B-1, and B-2 bombers. span, MARFORPAC controls two-thirds of

Marine Corps forces: the I Marine Expedi-

• U.S. Pacific Fleet. PACFLT normally tionary Force (MEF), centered on the 1st

controls all U.S. naval forces committed Marine Division, 3rd Marine Air Wing, and

to the Pacific, which usually represents 1st Marine Logistics Group, and the III Ma-

60 percent of the Navy’s fleet. It is orga- rine Expeditionary Force, centered on the

nized into Seventh Fleet, headquartered 3rd Marine Division, 1st Marine Air Wing,

in Japan, and Third Fleet, headquartered and 3rd Marine Logistics Group.49 The I

in California. Seventh Fleet comprises the MEF is headquartered at Camp Pendleton,

forward-deployed element of PACFLT California, and the III MEF is headquar-

and includes the only American carrier tered on Okinawa, although each has vari-

strike group (CTF-70) and amphibious ous subordinate elements deployed at any

group (CTF-76) home-ported abroad, time throughout the Pacific on exercises,

ported at Yokosuka and Sasebo, Japan, maintaining presence, or engaged in other

respectively. The Third Fleet’s area of activities. MARFORPAC is responsible

responsibility (AOR) spans the West for supporting three different commands:

Coast of the United States to the Interna- It is the U.S. Marine Corps component to

tional Date Line and includes the Alaskan PACOM, provides the Fleet Marine Forces

coastline and parts of the Arctic. There is to PACFLT, and provides Marine forces for

some discussion about whether to erase U.S. Forces Korea (USFK).50

The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org 143

• U.S. Special Operations Command Pa- • Resolute Support Mission, including U.S.

cific. SOCPAC has operational control of Forces Afghanistan.51

various special operations forces, includ-

ing Navy SEALs; Naval Special Warfare • Special Operations Joint Task Force—Af-

units; Army Special Forces (Green Berets); ghanistan. This includes a Special Forces

and Special Operations Aviation units in battalion, based out of Bagram Airfield,

the Pacific region, including elements in and additional allied special operations

Japan and South Korea. It supports the forces at Kabul.

Pacific Command’s Theater Security Co-

operation Program as well as other plans • 9th Air and Space Expeditionary Task

and contingency responses. Until 2015, Force. This includes the 155th Air Expedi-

this included Joint Special Operations tionary Wing, providing air support from

Task Force–Philippines (JSOTF-P), 500– Bagram airfield; the 451st Air Expedi-

600 soldiers assisting Manila in combat- tionary Group and 455th Expeditionary

ting Islamist insurgencies in the southern Operations Group, operating from Kan-

Philippines such as Abu Sayyaf. SOCPAC dahar and Bagram airfields, respectively,

forces also support various operations in providing air support and surveillance

the region other than warfighting, such operations over various parts of Afghani-

as counterdrug operations, counterter- stan; and the 421st Expeditionary Fighter

rorism training, humanitarian assistance, Squadron, providing close air support

and de-mining activities. from Bagram airfield.

• U.S. Forces Korea and U.S. Eighth • Combined Joint Task Force 10/10th

Army. Because of the unique situation Mountain Division, centered on Bagram

on the Korean peninsula, two subcom- airfield. This is the main U.S. national

ponents of PACOM, U.S. Forces Korea support element. It includes seven bat-

(USFK) and U.S. Eighth Army, are based in talions of infantry, air defense artillery for

Korea. USFK, a joint headquarters led by counter-artillery missions, and explosive

a four-star U.S. general, is in charge of the ordnance disposal across Afghanistan. It

various U.S. military elements on the Ko- also includes three Army aviation bat-

rean peninsula. U.S. Eighth Army operates talions, a combat aviation brigade head-

in conjunction with USFK as well as with quarters, and two additional joint task

the United Nations presence in the form forces to provide nationwide surveillance

of United Nations Command. support.52

Other forces, including space capabilities, • Five Train, Advise, Assist Commands in

cyber capabilities, air and sealift assets, and Afghanistan, each of which is a multina-

additional combat forces, may be made avail- tional force tasked with improving local

able to PACOM depending on requirements capabilities to conduct operations.53

and availability.

U.S. Central Command—Afghanistan. Key Infrastructure That Enables

Unlike the U.S. forces deployed in Japan and Expeditionary Warfighting Capabilities

South Korea, there is not a permanent force Any planning for operations in the Pacific

structure committed to Afghanistan; instead, will be dominated by the “tyranny of distance.”

forces rotate through the theater under the di- Because of the extensive distances that must

rection of PACOM’s counterpart in that region be traversed in order to deploy forces, even

of the world, U.S. Central Command (CENT- Air Force units will take one or more days to

COM). As of May 2016, these forces included: deploy, while ships measure steaming time in

144 2017 Index of U.S. Military Strength

weeks. For instance, a ship sailing at 20 knots and Andersen Air Force Base, one of a handful

requires nearly five days to get from San Di- of facilities that can house B-2 bombers. U.S.

ego to Hawaii. From there, it takes a further task forces, meanwhile, can stage out of Apra

seven days to get to Guam, seven days to Yo- Harbor, drawing weapons from the Ordnance

kosuka, Japan, and eight days to Okinawa—if Annex in the island’s South Central Highlands.

ships encounter no interference along the There is also a communications and data relay

journey.54 facility on the island.

China’s growing anti-access/area denial Over the past 20 years, Guam’s facilities

(A2/AD) capabilities, ranging from an expand- have steadily improved. B-2 bombers, for ex-

ing fleet of modern submarines to anti-ship ample, began operating from Andersen Air

ballistic and cruise missiles, increase the op- Force Base in 2005.55 These improvements

erational risk for deployment of U.S. forces in have been accelerated and expanded even as

the event of conflict. China’s capabilities not China’s A2/AD capabilities have raised doubts

only jeopardize American combat forces that about the ability to sustain operations in the

would flow into the theater for initial combat, Asian littoral. The concentration of air and

but also would continue to threaten the lo- naval assets as well as logistical infrastruc-

gistical support needed to sustain American ture, however, makes the island an attractive

combat power for the subsequent days, weeks, potential target in the event of conflict.

and months. The U.S. military has non-combatant mari-

American basing structure in the Indo– time prepositioning ships (MPS), which con-

Pacific region, including access to key allied tain large amounts of military equipment and

facilities, is therefore both necessary and in- supplies, in strategic locations from which

creasingly at risk. they can reach areas of conflict relatively

quickly as associated U.S. Army or Marine

American Facilities Corps units located elsewhere arrive in the

Much as in the 20th century, Hawaii re- areas. The U.S. Navy has units on Guam and in

mains the linchpin of America’s ability to sup- Saipan, Commonwealth of the Northern Mar-

port its position in the Western Pacific. If the ianas, which support prepositioning ships

United States cannot preserve its facilities in that can supply Army or Marine Corps units

Hawaii, then both combat power and sustain- deployed for contingency operations in Asia.

ability become moot. The United States main-

tains air and naval bases, communications in- Allied and Friendly Facilities

frastructure, and logistical support on Oahu For the United States, access to bases in

and elsewhere in the Hawaiian Islands. Ha- Asia has long been a prerequisite for support-

waii is also a key site for undersea cables that ing any American military operations in the

carry much of the world’s communications region. Even with the extensive aerial refu-

and data, as well as satellite ground stations. eling and underway replenishment skills of

The American territory of Guam is locat- the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy, it is still es-

ed 4,600 miles farther west. Obtained from sential for the United States to retain access

Spain as a result of the Spanish–American to resupply and replenishment facilities, at

War, Guam became a key coaling station for least in peacetime. The ability of those facili-

U.S. Navy ships. Seized by Japan in World War ties not only to survive, but also to function

II, it was liberated by U.S. forces in 1944 and will directly influence the course of any con-

after the war became an unincorporated, or- flict in the Western Pacific region. Moreover,

ganized territory of the United States. Key U.S. a variety of support functions, including com-

military facilities on Guam include U.S. Naval munications, intelligence, and space support,

Base Guam, which houses several attack sub- cannot be accomplished without facilities in

marines and may add an aircraft carrier berth, the region.

The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org 145

At the present time, it would be extraordi- Because of local resistance, construction of

narily difficult to maintain maritime domain the Futenma Replacement Facility at Camp

awareness or space situational awareness Schwab will not be complete until 2025, but

without access to facilities in the Asia–Pacific the U.S. and Japanese governments have af-

region. The American alliance network, out- firmed their support for the project.

lined previously, is therefore a matter both of South Korea. The United States also

political partnership and also of access to key maintains an array of facilities in South Korea,

facilities on allied soil. with a larger Army footprint than in Japan, as

Japan. In Japan, the United States has ac- the United States and South Korea remain fo-

cess to over 100 different facilities, including cused on deterring North Korean aggression

communications stations, military and de- and preparing for any possible North Korean

pendent housing, fuel and ammunition depots, contingencies. The Army maintains four ma-

and weapons and training ranges. This access jor facilities (which in turn control a number

comes in addition to major bases such as air of smaller sites) at Daegu, Yongsan in Seoul,

bases at Misawa, Yokota, and Kadena and na- and Camps Red Cloud/Casey and Humphreys.

val facilities at Yokosuka, Atsugi, and Sasebo. These facilities support the U.S. 2nd Infantry

The naval facilities support the USS Ronald Division, which is based in South Korea. Oth-

Reagan carrier strike group (CSG), which is er key facilities include air bases at Osan and

home-ported in Yokosuka, as well as a Marine Kunsan as well as a naval facility at Chinhae

Expeditionary Strike Group (ESG) centered near Pusan.

on the USS Bonhomme Richard, home-ported The Philippines. In 1992, The United

at Sasebo. Additionally, the skilled work force States ended nearly a century-long presence

at places like Yokosuka is an integral part of in the Philippines when it withdrew from

maintaining American forces and repairing its base in Subic Bay as its lease there ended.

equipment in time of conflict. Replacing them Clark Air Base had been closed earlier due to

would take years. This combination of facili- the eruption of Mount Pinatubo; the costs of

ties and work force, in addition to physical repairing the facility were deemed too high

location and political support, makes Japan to be worthwhile. In 2014, however, with the

an essential part of any American military growing Chinese assertiveness in the South

response to contingencies in the Western Pa- China Sea, including against Philippine

cific. Japanese financial support for the Amer- claims such as Mischief Reef and Scarbor-

ican presence also makes these facilities some ough Shoal, the U.S. and the Philippines nego-

of the most cost-effective in the world. tiated the EDCA, which will allow for the ro-

The status of one critical U.S. base has been tation of American forces through Philippine

a matter of public debate in Japan for many military bases.

years. The U.S. Marine Corps’ Third Marine In 2016, the two sides agreed on an initial

Expeditionary Force, based on Okinawa, is list of five bases in the Philippines that will be

the U.S.’s rapid reaction force in the Pacific. involved. Geographically distributed across

The Marine Air-Ground Task Force, com- the country, they are Antonio Bautista Air

prised of air, ground, and logistics elements, Base (in Palawaan closest to the Spratlys);

enables quick and effective response to crisis Basa Air Base (on the main island of Luzon

or humanitarian disasters. In response to lo- and closest to the hotly contested Scarbor-

cal protests, the Marines are reducing their ough Shoal); Fort Magsaysay (also on Luzon

footprint by relocating some units to Guam and the only facility on the list that is not

as well as to less-populated areas of Okinawa. an air base); Lumbia Air Base (in Mindanao

The latter includes moving a helicopter unit where Manila remains in low-intensity com-

from Futenma to a new facility in a more bat with Islamist insurgents); and Mactan-

remote location in northeastern Okinawa. Benito Ebuen Air Base (central Philippines).56

146 2017 Index of U.S. Military Strength

It remains unclear precisely which forces equipment.” 60 The Marines do not constitute

would be rotated through the Philippines a permanent presence in Australia, in keep-

as a part of this agreement, which in turn ing with Australian sensitivities about per-

affects the kinds of facilities that would be manent American bases on Australian soil.61

most needed. However, outside the context Similarly, the United States jointly staffs the

of the EDCA, the U.S. deployed E/A-18G Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap and the Joint

Growler electronic attack, A-10 Warthog Geological and Geophysical Research Station

close air support aircraft, and Pavehawk he- at Alice Springs and has access to the Har-

licopters to the Philippines in 2016.57 The old E. Holt Naval Communication Station in

base upgrades and deployments pursuant to Western Australia, including the space sur-

the EDCA are part of a broader expansion of veillance radar system there.62

U.S.–Philippine defense ties, which most re- Finally, the United States is granted ac-

cently included the U.S. leaving behind men cess to a number of facilities in Asian states

and matériel at Clark Air Base following an- on a contingency or crisis basis. Thus, U.S. Air

nual exercises,58 as well as joint naval patrols Force units transited Thailand’s U-Tapao Air

and increased levels of assistance under the Base and Sattahip Naval Base during the first

Maritime Security Initiative (MSI). The Gulf War and in the Iraq War, but they do not

Philippines is receiving the bulk of assis- maintain a permanent presence there. Addi-

tance in the first year of this five-year $425 tionally, the U.S. Navy conducts hundreds of

million program. port calls throughout the region.

Singapore. The United States does not Diego Garcia. Essential to U.S. operations

have bases in Singapore but is allowed access in the Indian Ocean and Afghanistan and pro-

to several key facilities that are essential for viding essential support to both the Middle

supporting American forward presence. Since East and East Asia are the American facilities

the closure of its facilities at Subic Bay, the on the British territory of Diego Garcia. The

United States has been allowed to operate the island is home to the 12 ships of Maritime

principal logistics command for the Seventh Prepositioning Squadron (MPS)-2, which can

Fleet out of the Port of Singapore Authority’s support a Marine brigade and associated Navy

(PSA) Sembawang Terminal. The U.S. Navy elements for 30 days. There are also several el-

also has access to Changi Naval Base, one of ements of the U.S. global space surveillance and

the few docks in the world that can handle a communications infrastructure on the island,

100,000-ton American aircraft carrier. In ad- as well as basing facilities for the B-2 bomber.

dition, a small U.S. Air Force contingent oper-

ates out of Paya Lebar Air Base to support U.S. Conclusion

Air Force combat units visiting Singapore and The Asian strategic environment is ex-

Southeast Asia, and Singapore hosts two new tremely expansive, as it spans half the globe,

Littoral Combat Ships (LCS) (with the option with a variety of political relationships among

of hosting two more) and a rotating squadron states that have wildly varying capabilities.

of F-16 fighter aircraft.59 The region includes long-standing American

Australia. A much-discussed element of allies with relationships dating back to the

the “Asia pivot” has been the 2011 agreement beginning of the Cold War as well as recently

to deploy U.S. Marines to Darwin in northern established states and some long-standing ad-

Australia. While planned to amount to 2,500 versaries such as North Korea.

Marines, the rotations fluctuate and have American conceptions of the region must

not yet reached that number. “In its mature therefore start from the physical limitations

state, the Marine Rotational Force–Darwin imposed by the tyranny of distance. Mov-

(MRF-D) will be a Marine Air-Ground Task ing forces within the region, never mind to it,

Force…with a variety of aircraft, vehicles and will take time and require extensive strategic

The Heritage Foundation | heritage.org 147

lift assets as well as sufficient infrastructure especially unresolved historical and territo-

(such as sea and aerial ports of debarkation rial issues, means that, unlike Europe, the

that can handle American strategic lift assets) United States cannot necessarily count on

and political support. At the same time, the support from all of its regional allies in event

complicated nature of intra-Asian relations, of any given contingency.

Scoring the Asia Operating Environment

As with the operating environments of environment. The U.S. military is well