Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mastilep Gel Dry Cow Therapy

Uploaded by

prafulwonderfulCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mastilep Gel Dry Cow Therapy

Uploaded by

prafulwonderfulCopyright:

Available Formats

World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research

Yadav et al. SJIF Impact

World Journal of Pharmaceutical Factor 7.523

Research

Volume 6, Issue 5, 675-680. Research Article ISSN 2277– 7105

EFFICACY OF HERBAL REMEDIES AS ALTERNATIVE TO

ANTIBIOTICS IN DRY COW THERAPY

Hadiya K.1, Vikas Yadav2*, Anurag Borthakur2, K. Ravikanth2, Shivi Maini2

1

Dairy Farm Consultant Anand

2

Clinical R&D Department, Ayurvet Limited, Baddi, H.P. India.

ABSTRACT

Article Received on

01 March 2017,

A comparative trial was designed to evaluate the efficacy of topical

Revised on 20 March 2017, herbal gel- Mastilep gel (M/s Ayurvet limited) instead of using

Accepted on 10 April 2017

antibiotics as a dry cow therapy. Total 30 Crossbred advance pregnant

DOI: 10.20959/wjpr20175-8304

cow were selected, divided in to 3 groups T0, T1, and T2 having 10

numbers of cows in each. Group T0 was kept as control. In group T1,

*Corresponding Author

dry cow therapy started with herbal gel- Mastilep for 5 days (before

Dr. Vikas Yadav

drying off) and 5 days (after calving). In group T2 dry cow therapy

Dairy Farm Consultant

Anand. was done by using Enrofloxacin, synthetic antibiotic injection (fortvir

30mg), 2 injection at 72 hour interval, I/M. Results revealed that in the

control group (T0) SCC (X103) was increased from 183 on day 0 to 186 on 5th day and in

absence of any treatment overall SSC further increased up to 203 on 3rd day after parturition.

In Group T1, the overall SCC (X103) was reduced from 187 on day 0 to 147 on 3rd day after

parturition. . In group T2, the overall SCC (X103) was 189 on day 0 which reduced to 182 on

3rd day after parturition. On 3rd day after parturition, milk production (liter/day) was

significantly more in group T1 (14.95) followed by group T2 (14.56) further followed by

group T0 (10.96).

KEYWORDS: Mastilep gel, Somatic Cell Count (SCC), milk production.

INTRODUCTION

Mastitis is an inflammation of the mammary gland which, together with physical, chemical

and microbiological changes, is characterized by an increase in the number of somatic cells in

the milk and by pathological changes in the mammary tissue.[1] Inflammations of the

mammary glands, mastitis, are one of the most costly health issues faced by dairy farms.

Mastitis is a global problem as it adversely affects animal health, quality of milk and the

www.wjpr.net Vol 6, Issue 5, 2017. 675

Yadav et al. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research

economics of milk production, affecting every country, including developed ones and causes

huge financial losses.[2] There is agreement among authors that mastitis is the most

widespread infectious disease in dairy cattle, and, from an economic aspect, the most

damaging.[3,4] Mastitis, the most common multifactorial disease in the lactating cow has

remarkably rising impact on Indian economy where over all losses due to mastitis is

estimated to be Rs.7165.51 crores.[5,6] In cows, mastitis is most frequently caused by a

bacterial infection. Infections may be present in the clinical form characterized by visible

abnormalities in the milk or the udder or in subclinical form characterized by inflammation of

the mammary gland that does not create visible changes in the milk or the udder. Infections

may not present as clinical cases during the dry period, there is a high risk that subclinical

cases will become clinical after calving.[7] In contrast, detection of mammary quarters with

sub-clinical mastitis is more difficult because signs are not readily apparent [8] and, because of

the lack of any overt manifestation, its diagnosis is a challenge in dairy animal management

and in veterinary practice. The sub-clinical form is 15 to 40 times more prevalent than the

clinical form, and usually precedes the clinical form and is of long duration.[9] It is important

to emphasize that the sub-clinically affected animals remain a continuing source of infection

for herd mates.[10] There are different levels for detection of mastitis: an individual cow level

in the herd, and a more large-scale testing for bulk milk[8]. Regarding the individual cow

level, the sub-clinical form of the disease can be detected by bacteriological examination and

somatic cell counts (SCC).[11] Various antibiotic based intra-mammary infusions for the both

dry cow therapy and the treatment of mastitis are available. However the increasing

emergence of antibiotic resistant pathogens.[12] is further suspected to complicate the

effectiveness of the mastitis treatment. Both pre and post milking teat antiseptics are the most

effective management strategy for preventing new intra mammary infections in dairy cows.

Prophylactic antibiotic dry cow therapy, administered at the end of lactation, aims to

eliminate current and prevent future intra-mammary infections. Certified organic dairies are

restricted from antibiotic use and thus must use an alternative or no dry cow therapy. Teat

disinfection after milking is one of the five plans of mastitis control by National Institute of

Research in to Dairying (NIRD).[13] Several herbal extracts have shown in vitro antibacterial

activity versus major mastitis pathogens.[14] WHO has also emphasized on the use of

medicinal plant, therefore the proposed study was to assess herbal product, Mastilep gel (M/s

Ayurvet limited) for treatment or prevention of mastitis as alternative to antibiotics.

www.wjpr.net Vol 6, Issue 5, 2017. 676

Yadav et al. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The proposed study was carried out at dairy farm, Anand, Gujrat, to evaluate the efficacy of

Mastilep gel and Antibiotics (Inj. Enrofloxacin 10mg/kg i/m repeat 72hrs Interval) in the

treatment of Dry Cow Therapy. A total of 30 Crossbred cows were selected with the history

of advance pregnant and near about dry off for next lactation. All the selected cows were

reported to have a history of sub clinical or clinical mastitis in present lactation. The group

T0 was kept as control and given no antibiotic or herbal therapy (no dry off treatment),

treatment group T1 was treated with Mastilep gel, BID application for 5 days after dry off to

be repeated after calving for 5 days and treatment group T2 given dry off therapy with

Antibiotic, two Injection of Enrofloxacin at interval of 72 hrs after dry off. Duplicate quarter

milk samples were taken immediately before dry treatment and three days post-calving. A

change in bacterial presence between pre-treatment and post-calving samples for each cow

was used to determine the efficacy of each treatment. A somatic cell count from the pre-

treatment lactation and during the early part of the subsequent lactation was compared among

treatments to determine practical effects of treatment. Therapeutic efficacy was determined

on the basis of improvement in the somatic cell count, milk yield and milk fat content.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The data shows the effect of the dry cow therapy was very much effective in the Mastilep gel

treated group (T1) as compared to control group (T0) in terms of the incidence of mastitis. It

was revealed that the somatic cell count was also reduced in the mastilep treated group (T1)

and animal reach peak production in short time as compared with the control group (T0). The

incidence of mastitis was different in Mastilep Gel treated group and Antibiotics treated

group as compared to control group. But the somatic cell counts were less in Mastilep Gel

treated group as compared to antibiotics Treatment groups (Table No 1). There was no

significant difference in milk production in both treatment groups except control group.

Decrease in the somatic cell count as well as increase in milk production may be due to

presence of higher concentrations of flavonoids, saponins, glycosides, alkaloids and

[15]

terpenoids in the extracts of Cedrus deodara which have anti-bacterial, anti-fungal and

anti-inflamatory properties and Curcuma longa (Turmeric), which is also constituent

ingredient of herbal gel mastilep, possesses numerous pharmacological activities, including

antioxidant and antimicrobial properties and its use for inflammatory conditions is also well

known [16]. Bcteria such as S. aureus, S. agalactiae , E. coli and Pseudomonas aeroginosa are

the most common etiological agents involved in subclinical cases of mastitis in dairy

www.wjpr.net Vol 6, Issue 5, 2017. 677

Yadav et al. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research

cows[17]. The antibacterial activities of essential oils from leaves of Eucalyptus globules, also

a constituent ingredient of mastilep gel, was determined against Staphylococcus aureus Gram

(+) and Escherichia coli Gram (-) bacteria.[18]. So the improvement in the milk production as

well as SCC is may be due to consequent of pharmacological activity of the ingredients used

in the herbal gel – Mastilep.

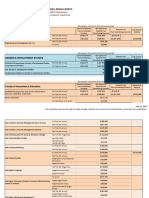

Table No 1: Overall performance

Average milk

% Animal

Total No. of No. of animals Average SSC production

Group name affected in

animals affected (X103) per animal /

group

day(lit)

Control

10 4 40 203 10.96

Group (T0)

Treatment

10 1 10 147 14.95

Group (T1)

Treatment

10 1 10 182 14.56

Group2

CONCLUSION

Efficacy of herbal gel- Mastilep, in the treatment of subclinical mastitis was good among the

control and antibiotic treated group. Also the increase in the milk yield was more in the

Mastilep gel treated group. Therefore application of the herbal-gel Mastilep may be

recommended for the treatment and control of sub clinical mastitis in bovine.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors are thankful to Ayurvet Limited, Baddi, India and Anand dairy farm, Gujarat for

providing the required facilities, guidance and support.

REFERENCES

1. Gianneechini R, Concha C, Rivero R, Delucci I, Moreno L J. Occurrence of Clinical and

Sub-Clinical Mastitis in Dairy Herds in the West Littoral Region in Uruguay.Acta

Veterinaria Scandinavica. 2002; 43: 221.

2. Sharma N, Maiti SK, Sharma KK. Prevalence, etiology and antiobiogram of micro-

organisms associated with sub-clinical mastitis in buffaloes in Durg, Chhattisgrh State

(India). International Journal of Dairy Science 2007; 2(2): 145–151.

3. Elango A, Doraisamy KA, Rajarajan G, Kumaresan G. Bacteriology of sub-clinical

mastitis and anti-biogram of isolates recovered from cross-bred cows. Indian Journal of

Animal Research 2010; 44(4): 280–284.

www.wjpr.net Vol 6, Issue 5, 2017. 678

Yadav et al. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research

4. Sharma N, Rho GY, Hong YH, Lee TY, Hur TY. & Jeong DK. Bovine mastitis: an

Asian perspective. Asian Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances 2012; 7: 454–476.

5. Bansal BK, Gupta DK. Economic analysis of bovine mastitis in India and Panjab A

review. Indian JdAIRY Sci, 2009; 67: 337-45.

6. Halsa T, Huijps K, Osteras O, Hogeveen H. Economic effects of bovine mastitis and

mastitis management. A review Vet Q, 2007; 72-88.

7. Green MJ, Green LE, Medley GF, Schukken YH, Bradley AJ. Influence of dry period

bacterial intramammary infection on clinical mastitis in dairy cows. Journal of Dairy

Science. 2002; 85: 2589–2599.

8. Kivaria FM. Epidemiological studies on bovine mastitis in smallholder dairy herds in the

Dar es Salaam Region, Tanzania. Doctoral thesis, Utrecht University, The Netherlands

2006.

9. Seegers H, Fourichon C, Beaudeau F. Production effects related to mastitis and mastitis

economics in dairy cattle herds. Veterinary Research 2003; 34: 475–491.

10. Islam MA, Islam MZ, Islam MA, Rahman, MS, Islam MT. Prevalence of sub-clinical

mastitis in dairy cows in selected areas of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Veterinary

Medicine 2011; 9(1): 73–78.

11. Muhammad G, Naureen A, Nadeem Asi, Saqib M, Fazul-ur-Rehman. Evaluation of a

3% Surf solution (Surf Field Mastitis Test) for the diagnosis of sub-clinical bovine and

bubaline mastitis. Tropical Animal Health and Production. 2010; 42: 457-464.

12. Nakavuma J, Byarugaba DK, Mussi LN, Kitimbo FX. Microbiological diagnosis and

drug resistance patterns of infectious cause of mastitis. Uganda Journal of agricultural

sciences, 1994; 2: 22-8.

13. Bradley A, Geen M, Breen J, Hudson C, Dairy Co Mastitis Control plan- three year report

2008-2012. DairyCo., 2012; 1-50.

14. Yi-Zhong Cai, John D. Brooks, Harold Corke, Bin Shan. The in vitro antibacterial

activity of dietary spice and medicinal herb extracts, International journal of food

microbiology. July 2007; 117(1): 112-9.

15. Chaudhary AK, Ahmad S, Mazumder A. Study of antibacterial and antifungal activity

of traditional Cedrus deodara and Pinus roxburghii Sarg . Humanitas medicine. 2012;

2(4).

16. Jurenka JS. Anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin, a major constituent of Curcuma

longa: a review of preclinical and clinical research. Altern Med Rev. 2009; 14(3): 277.

www.wjpr.net Vol 6, Issue 5, 2017. 679

Yadav et al. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research

17. Abdel-Rady A, Sayed M. Epidemiological Studies on Subclinical Mastitis in Dairy cows

in Assiut Governorate. Veterinary World. October 2009; 2(10): 373-380.

18. Bachir Raho, Ghalem, Benali Mohamed. Antibacterial activity of leaf essential oils of

Eucalyptus globulus and Eucalyptus camaldulensis. African Journal of Pharmacy and

Pharmacology. 2008; 2(10): 211-215.

www.wjpr.net Vol 6, Issue 5, 2017. 680

You might also like

- Mastitis Vaccines in Dairy Cows - Recent Developments and Recommendations of ApplicationDocument6 pagesMastitis Vaccines in Dairy Cows - Recent Developments and Recommendations of ApplicationVo Thanh ThinNo ratings yet

- In vitro anti-diabetic and anti-inflammatory activity of Bauhinia purpurea stem bark extractsDocument12 pagesIn vitro anti-diabetic and anti-inflammatory activity of Bauhinia purpurea stem bark extractsRajesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Sida VeronicaefeliaDocument5 pagesSida VeronicaefeliaNovitasari SNo ratings yet

- 2010 - Klocke Et Al. - A Randomized Controlled Trial To Compare The Use of Homeopathy and Internal Teat Sealers For The Prevention of MaDocument9 pages2010 - Klocke Et Al. - A Randomized Controlled Trial To Compare The Use of Homeopathy and Internal Teat Sealers For The Prevention of MaThais LompaNo ratings yet

- Homoeopathic and allopathic treatments increase milk quality in mastitic buffaloesDocument3 pagesHomoeopathic and allopathic treatments increase milk quality in mastitic buffaloesDinesh KumarNo ratings yet

- A Short Drug Trial of Mastitis in Cattle: November 2013Document4 pagesA Short Drug Trial of Mastitis in Cattle: November 2013vetthamilNo ratings yet

- Flax ingestion may promote hair growth in rabbitsDocument5 pagesFlax ingestion may promote hair growth in rabbitsdhafer alhaidaryNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Activityof Psidium Guajava Leaves Extract Against Foodborne PathogensDocument9 pagesAntimicrobial Activityof Psidium Guajava Leaves Extract Against Foodborne Pathogensuniqlu9No ratings yet

- Deber 1 Articulo 1Document10 pagesDeber 1 Articulo 1Tammy CevallosNo ratings yet

- MasSub Epizoo-LaktasiDocument7 pagesMasSub Epizoo-LaktasiAprilia HardiNo ratings yet

- Effect of Cinnamaldehyde On Female Reproductive Hormones in 7, 12 Dimethyl Benzanthracene Induced Ovarian Cancer RatsDocument7 pagesEffect of Cinnamaldehyde On Female Reproductive Hormones in 7, 12 Dimethyl Benzanthracene Induced Ovarian Cancer RatsIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- The Informative Value of An Overview On Antibiotic Consumption, Treatment Efficacy and Cost of Clinical Mastitis at Farm LevelDocument8 pagesThe Informative Value of An Overview On Antibiotic Consumption, Treatment Efficacy and Cost of Clinical Mastitis at Farm LeveljsolvarelaNo ratings yet

- Effectivenessof Aqueous Extractof Fenugreek Seedsand Flaxseedon 2019Document13 pagesEffectivenessof Aqueous Extractof Fenugreek Seedsand Flaxseedon 2019zmk KNo ratings yet

- BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Antiinflammatory Evaluation of Leaves of Plumeria AcuminataDocument6 pagesBMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Antiinflammatory Evaluation of Leaves of Plumeria AcuminatadianapriyaniNo ratings yet

- Effect of Probiotic and Prebiotic As Antibiotic Growth Promoter Substitutions On Productive and Carcass Traits of Broiler ChicksDocument5 pagesEffect of Probiotic and Prebiotic As Antibiotic Growth Promoter Substitutions On Productive and Carcass Traits of Broiler ChicksSureshCoolNo ratings yet

- Recent Perspectives of Growth Promoters in Livestock: An OverviewDocument12 pagesRecent Perspectives of Growth Promoters in Livestock: An OverviewNiranjan HegdeNo ratings yet

- Antidiabetic, Antihyperlipidemic and Antioxidant Properties of Roots of Ventilago Maderaspatana Gaertn. On StreptozotocinInduced Diabetic RatsDocument10 pagesAntidiabetic, Antihyperlipidemic and Antioxidant Properties of Roots of Ventilago Maderaspatana Gaertn. On StreptozotocinInduced Diabetic RatsIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Probiotics and Antibiotic Growth PromoterDocument7 pagesThe Influence of Probiotics and Antibiotic Growth PromoterOliver TalipNo ratings yet

- Current Treatment Aspects of Bovine Reproductive DisordersDocument10 pagesCurrent Treatment Aspects of Bovine Reproductive DisordersTatiana LageNo ratings yet

- Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine: Original Research Article (Experimental)Document6 pagesJournal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine: Original Research Article (Experimental)Said abdul jalil GassppooeellNo ratings yet

- Cow - Neomycin - 500 MGDocument9 pagesCow - Neomycin - 500 MGyulianaNo ratings yet

- Acute & Chronic Toxicity Studies of Seenthil SarkaraiDocument12 pagesAcute & Chronic Toxicity Studies of Seenthil SarkaraiManickavasagam RengarajuNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Herbs On Milk Yield and Milk QualityDocument7 pagesThe Effect of Herbs On Milk Yield and Milk QualityAbery AuNo ratings yet

- The Effect of A Compound Protein On Wound HealingDocument12 pagesThe Effect of A Compound Protein On Wound HealingyuniNo ratings yet

- Al., 2019), Bacteriophages, Nanoparticles (Gomes And: C. Short CommunicationDocument9 pagesAl., 2019), Bacteriophages, Nanoparticles (Gomes And: C. Short CommunicationPatriciaCardosoNo ratings yet

- FicusDocument3 pagesFicusSugandha ShetyeNo ratings yet

- Ijsid: International Journal of Science Innovations and DiscoveriesDocument9 pagesIjsid: International Journal of Science Innovations and DiscoveriesijsidonlineinfoNo ratings yet

- Grape Seed Extract: Having A Potential Health BenefitsDocument11 pagesGrape Seed Extract: Having A Potential Health BenefitsGabriel GursenNo ratings yet

- Vet Clin Food Anim Mastitis Therapy PharmacologyDocument30 pagesVet Clin Food Anim Mastitis Therapy PharmacologyAndres Alejandro CoralNo ratings yet

- Phytobiotics Habbatus Sauda and Garlic Meal: Are Still Efficacious During The Spread of Marek's Disease OutbreakDocument5 pagesPhytobiotics Habbatus Sauda and Garlic Meal: Are Still Efficacious During The Spread of Marek's Disease OutbreakerwinkukuhNo ratings yet

- Management and ProductionDocument11 pagesManagement and ProductionTechdevtodo DevtodoNo ratings yet

- Potential Role of Important Nutraceuticals in Poultry Performance and Health - A Comprehensive ReviewDocument21 pagesPotential Role of Important Nutraceuticals in Poultry Performance and Health - A Comprehensive ReviewUmmul MasirNo ratings yet

- Biochemical and Pathological Effects of Palm, Mustard and Soybean Oils in RatsDocument9 pagesBiochemical and Pathological Effects of Palm, Mustard and Soybean Oils in RatsArshad Rezwan AbidNo ratings yet

- Author's Accepted Manuscript: Azadirachta Indica Helicobacter PyloriDocument29 pagesAuthor's Accepted Manuscript: Azadirachta Indica Helicobacter PyloriMiguel Angel Quispe SolanoNo ratings yet

- Kayria Mapandi JunaidDocument9 pagesKayria Mapandi JunaidBarie ArnorolNo ratings yet

- JWorldPoultRes84105 1102018 PDFDocument6 pagesJWorldPoultRes84105 1102018 PDFIlham ArdiansahNo ratings yet

- tmpECD6 TMPDocument10 pagestmpECD6 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- American Journal of Biomedical and Life SciencesDocument11 pagesAmerican Journal of Biomedical and Life SciencesTrivedi EffectNo ratings yet

- Monitoring Udder Health and Milk Quality Using Somatic Cell CountsDocument19 pagesMonitoring Udder Health and Milk Quality Using Somatic Cell CountsMichele AlvesNo ratings yet

- qnZNA7 PDFDocument6 pagesqnZNA7 PDFjyothi BasiniNo ratings yet

- Somatic Cell Count and Type of Intramammary Infection Impacts Fertility in Vitro Produced Embryo TransferDocument6 pagesSomatic Cell Count and Type of Intramammary Infection Impacts Fertility in Vitro Produced Embryo TransferalineNo ratings yet

- Bovine Mastitis An Appraisal of Its Alte BUIATRIADocument18 pagesBovine Mastitis An Appraisal of Its Alte BUIATRIALysett CoronaNo ratings yet

- Research Article Artemisia Kopetdaghensis: Evaluation of Cytotoxicity and Antifertility Effect ofDocument6 pagesResearch Article Artemisia Kopetdaghensis: Evaluation of Cytotoxicity and Antifertility Effect ofLinguumNo ratings yet

- Plant Disease Management Strategies for Sustainable Agriculture through Traditional and Modern ApproachesFrom EverandPlant Disease Management Strategies for Sustainable Agriculture through Traditional and Modern ApproachesImran Ul HaqNo ratings yet

- tmp3DA2 TMPDocument11 pagestmp3DA2 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- 6 Ijasrfeb20186Document6 pages6 Ijasrfeb20186TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Growth Performance of Broilers Fed Different Levels of PrebioticsDocument7 pagesGrowth Performance of Broilers Fed Different Levels of PrebioticsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- MSC Project Presentation 29 MarchDocument36 pagesMSC Project Presentation 29 MarchdreamroseNo ratings yet

- Article Wjpps 1406694428 PDFDocument16 pagesArticle Wjpps 1406694428 PDFCaryl FrancheteNo ratings yet

- Microalgae For Immunomodulation and Gut Health Improvement in Poultry IndustryDocument6 pagesMicroalgae For Immunomodulation and Gut Health Improvement in Poultry IndustryevelNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research and Bio-ScienceDocument7 pagesInternational Journal of Pharmaceutical Research and Bio-SciencebaroliNo ratings yet

- Anti-Diabetic Activity Evaluation of The Bark of Cascabela Thevetia L. in Streptozotocin Induced Diabetic RatsDocument6 pagesAnti-Diabetic Activity Evaluation of The Bark of Cascabela Thevetia L. in Streptozotocin Induced Diabetic RatsNeelutpal16No ratings yet

- Treatment of Mastitis in Dairy CattleDocument30 pagesTreatment of Mastitis in Dairy CattleKalpak ShahaneNo ratings yet

- Melinjo JournalDocument10 pagesMelinjo JournalStephanie NangoiNo ratings yet

- Monitoring Udder and Milk With SCCDocument18 pagesMonitoring Udder and Milk With SCCDoris Banila San Martin OrellanaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Treatment With Tri-Sodium Citrate Alone and in Combination With Levamisole HCL On Total Milk Bacterial Count in Dairy Buffalo Suffering From Sub-Clinical MastitisDocument3 pagesEffect of Treatment With Tri-Sodium Citrate Alone and in Combination With Levamisole HCL On Total Milk Bacterial Count in Dairy Buffalo Suffering From Sub-Clinical MastitisAyman VetoNo ratings yet

- Formulation and Evaluation of Topical Gel Using Eupatorium Glandulosummichx For Wound Healing ActivityDocument12 pagesFormulation and Evaluation of Topical Gel Using Eupatorium Glandulosummichx For Wound Healing ActivityTri Dewi AstutiNo ratings yet

- Cow and goat urine inhibit dental caries pathogensDocument5 pagesCow and goat urine inhibit dental caries pathogensChand RaviNo ratings yet

- Use of Ethno-Veterinary Medicine For Therapy of Reprod DisordersDocument11 pagesUse of Ethno-Veterinary Medicine For Therapy of Reprod DisordersgnpobsNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0270350Document18 pagesJournal Pone 0270350Priscila MoraesNo ratings yet

- Cotton Seed Meal in Broiler Layer Diet 11Document5 pagesCotton Seed Meal in Broiler Layer Diet 11prafulwonderfulNo ratings yet

- Use of Guar Meal in Poultry 13Document2 pagesUse of Guar Meal in Poultry 13prafulwonderfulNo ratings yet

- DA-DP Process MapDocument1 pageDA-DP Process MapmanthanlakhaniNo ratings yet

- Embryonic Growth RossDocument1 pageEmbryonic Growth RossprafulwonderfulNo ratings yet

- Residue Detection ProgramDocument18 pagesResidue Detection ProgramprafulwonderfulNo ratings yet

- Cobb Vaccination Procedure Guide EnglishDocument38 pagesCobb Vaccination Procedure Guide EnglishRed PhoenixNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Residue in Poultry and Egg USDA PDFDocument4 pagesAntibiotic Residue in Poultry and Egg USDA PDFprafulwonderfulNo ratings yet

- MethiorepDocument4 pagesMethiorepprafulwonderfulNo ratings yet

- CH 09Document16 pagesCH 09KittiesNo ratings yet

- Tridosha Made Easy The Basic Ayurvedic Principle (Janardhana V Hebbar, Raghuram Ys, Manasa S)Document621 pagesTridosha Made Easy The Basic Ayurvedic Principle (Janardhana V Hebbar, Raghuram Ys, Manasa S)Sumit SardarNo ratings yet

- Investigations For Diseases of The Tongue A Review PDFDocument6 pagesInvestigations For Diseases of The Tongue A Review PDFShantanu DixitNo ratings yet

- Substance Abuse Counseling Complete 5th EditionDocument379 pagesSubstance Abuse Counseling Complete 5th Editionnintendoagekid86% (59)

- American Psycho Disorders & TriggersDocument5 pagesAmerican Psycho Disorders & TriggersPatricia SmithNo ratings yet

- Al Shehri 2008Document10 pagesAl Shehri 2008Dewi MaryamNo ratings yet

- Taking Blood Pressure CorrectlyDocument7 pagesTaking Blood Pressure CorrectlySamue100% (1)

- Peace Corps Medical Officer (PCMO) Job AnnouncementDocument3 pagesPeace Corps Medical Officer (PCMO) Job AnnouncementAccessible Journal Media: Peace Corps DocumentsNo ratings yet

- Drug Price ListDocument68 pagesDrug Price ListYadi Vanzraso SitinjakNo ratings yet

- HIV Prevention: HSCI 225 BY Mutua Moses MuluDocument23 pagesHIV Prevention: HSCI 225 BY Mutua Moses MuluJibril MohamudNo ratings yet

- Legal Aid ProjectDocument5 pagesLegal Aid ProjectUday singh cheemaNo ratings yet

- Audits, Gap Assessments, CAPA - 0Document230 pagesAudits, Gap Assessments, CAPA - 0mgvtertv100% (3)

- Which Is More Effective in Treating Chronic Stable Angina, Trimetazidine or Diltiazem?Document5 pagesWhich Is More Effective in Treating Chronic Stable Angina, Trimetazidine or Diltiazem?Lemuel Glenn BautistaNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmology 7th Edition (Oftalmología 7a Edición)Document1,671 pagesOphthalmology 7th Edition (Oftalmología 7a Edición)Víctor SaRi100% (1)

- CRS Report: Federal Employee Salaries and Gubernatorial SalariesDocument54 pagesCRS Report: Federal Employee Salaries and Gubernatorial SalariesChristopher DorobekNo ratings yet

- UWI-Mona 2021-2022 Graduate Fee Schedule (July 2021)Document15 pagesUWI-Mona 2021-2022 Graduate Fee Schedule (July 2021)Akinlabi HendricksNo ratings yet

- Emergency Drug Doses - PBS Doctor's Bag Items - Australian PrescriberDocument4 pagesEmergency Drug Doses - PBS Doctor's Bag Items - Australian PrescriberChhabilal BastolaNo ratings yet

- Allergen ControlDocument20 pagesAllergen Controlmedtaher missaoui100% (1)

- Diabetes and Hearing Loss (Pamela Parker MD)Document2 pagesDiabetes and Hearing Loss (Pamela Parker MD)Sartika Rizky HapsariNo ratings yet

- hf305 00 Dfu DeuDocument54 pageshf305 00 Dfu DeuMauro EzechieleNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Fundamental Nursing Skills and Concepts Tenth EditionDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Fundamental Nursing Skills and Concepts Tenth Editionooezoapunitory.xkgyo4100% (41)

- 3.material Science Eng. CDocument8 pages3.material Science Eng. CSanjeeb KalitaNo ratings yet

- eBR PharmaDocument5 pageseBR PharmaDiana OldaniNo ratings yet

- Stok Benang Kamar OperasiDocument5 pagesStok Benang Kamar OperasirendyNo ratings yet

- Ontario Works Service Delivery Model CritiqueDocument14 pagesOntario Works Service Delivery Model CritiquewcfieldsNo ratings yet

- Hemifacial Spasm A NeurosurgicalDocument8 pagesHemifacial Spasm A NeurosurgicaldnazaryNo ratings yet

- Semi Solids PDFDocument3 pagesSemi Solids PDFAsif Hasan NiloyNo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet SummaryDocument8 pagesSafety Data Sheet SummaryReffi Allifyanto Rizki DharmawamNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Care Plan - DysphagiaDocument1 pageNutrition Care Plan - DysphagiaElaine ArsagaNo ratings yet

- Mixed Connective Tissue DZ (SLE + Scleroderma)Document7 pagesMixed Connective Tissue DZ (SLE + Scleroderma)AshbirZammeriNo ratings yet