Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adam (2005) of Property and The Human - or CB Macpherson Samuel Hearne and Contemp Theory

Uploaded by

Miguel ReyesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Adam (2005) of Property and The Human - or CB Macpherson Samuel Hearne and Contemp Theory

Uploaded by

Miguel ReyesCopyright:

Available Formats

Of Property and the Human; or, C.B.

Macpherson, Samuel Hearne,

and Contemporary Theory

Carter, Adam.

University of Toronto Quarterly, Volume 74, Number 3, Summer

2005, pp. 829-844 (Article)

Published by University of Toronto Press

For additional information about this article

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/utq/summary/v074/74.3carter.html

Access Provided by Australian National University at 04/02/11 5:42AM GMT

ADAM CARTER

Of Property and the Human;

or, C.B. Macpherson, Samuel Hearne,

and Contemporary Theory

In a 1971 letter written to the Canadian political theorist and intellectual

historian Crawford Brough Macpherson, Isaiah Berlin praised Macpher-

son’s ‘rational and lucid and altogether admirable’ work and assured

Macpherson that ‘when the future generation sort things out the difference

between your kind of writing and the hideous inflated prose of the

Germans and their followers will be duly noted’ (qtd in Townsend, 5).

Many today would be unwilling to endorse Berlin’s characterization of

German, and more broadly Continental, theory, which has for the last

quarter-century at least been a productive source of ideas for the humani-

ties and social sciences. As well, we have become more suspicious in the

interim of the politics of a once much vaunted lucid English prose, its

combination of, in Geoffrey Hartman’s phrase, ‘tea and totality’ (236) in the

production of what David Simpson has called the ‘culture of British

commonsense’ (40). The ‘Germans and their followers’ have had a better

run of it than Berlin seems to have predicted and the ‘future generation’ to

which he refers has been guilty of hardly noticing C.B. Macpherson at all.

This present failure to notice Macpherson is, perhaps, nowhere more in

evidence than in the fields of literary and cultural criticism and theory

where one might most expect his legacy to have been taken up. Although

Macpherson had little enough to say directly about literature or the cultural

sphere outside the tradition of political theory to which he devoted his

career, he rightfully stands as one of the most significant historical-

materialist, critical theorists writing in English in the second half of the

twentieth century.1 His work provides a profound and challenging critique

1 Macpherson’s study of Burke is telling with respect to this lack of direct engagement with

issues narrowly cultural and aesthetic. The 1980s and early 1990s produced, in the work

of W.J.T. Mitchell, Frances Ferguson, and Terry Eagleton (The Ideology of the Aesthetic) ,

influential studies of the crossings of aesthetics and ideology in Edmund Burke’s treatise

on the sublime and beautiful, but Macpherson’s brief but engaging study of Burke

published in 1980 in the Past Masters series declines to treat Burke’s aesthetics at all,

dismissing it in a sentence as ‘of little theoretical interest’ (19). There is, however, no

shortage of theorists who have been influential in literary and cultural criticism though not

primarily engaged with the cultural or aesthetic sphere and I contend that Macpherson

deserves stature among them.

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

830 adam carter

of the formation of the subject, the modern individual – a critique

concerned most centrally with the subject’s connections to property

relations and the commodity form within developing capitalist economies

from the seventeenth century to the later twentieth century. Yet, while

historical-materialist critical theory, Marxist and otherwise, has played a

prominent and productive role in literary and cultural studies since the

1970s, alongside a wide array of other texts and traditions from psycho-

analysis to linguistics, semiotics, rhetoric, and continental philosophy

which have all fallen under the expansive rubric of ‘theory,’ a search of the

mla International Bibliography for C.B. Macpherson turns up no refer-

ences, a telling indication of how little his work has been engaged within

these fields.

Macpherson has enjoyed a greater prominence among political theorists,

particularly in Canada throughout the 1960s and 1970s, when he engaged

his many critics in debates in academic journals. Although James Tully has

described Macpherson’s central thesis of possessive individualism as having

been for a time ‘the reigning orthodoxy’ among political theorists (19), Jules

Townsend’s recent study of Macpherson argues convincingly that this was

never the case. Macpherson was too Marxist for his liberal critics of the

Cold War years of the 1950s and 1960s, too liberal for younger more radical

Marxist critics of the later 1960s and 1970s, and too totalizing, teleological

and essentializing for the postmodern ethos of the 1980s and 1990s (Town-

send 3, 99–129, 143–53). Nonetheless, within the field of political theory

Macpherson enjoyed a prominent stature, even if, for many, it was as the

chief representative of wrong-headed viewpoints that needed to be coun-

tered.

One can come across scattered, brief but approving references to

Macpherson’s work in such influential studies as Stephen Greenblatt’s

Renaissance Self-Fashioning (38, 263) and Charles Taylor’s Sources of the Self

(196), as well as in an endnote of an essay of Gayatri Spivak’s from the mid-

1980s, which, by way of referring to three theories of subject formation that

have been influential upon her, lists Macpherson’s The Political Theory of

Possessive Individualism and thanks the philosopher Jonathan Rée for

alerting her to the study (‘Three Woman’s Texts’ 260), thus giving Mac-

pherson’s book the air of a neglected but quietly circulating classic. Such

passing references attest to the possibilities of more sustained engagements

with Macpherson in contemporary theory, but where one might most

expect such an engagement – in the works of influential, wide-ranging, and

widely read Marxist theorists such as Terry Eagleton and Fredric Jameson

– there is no mention. These theorists have, rather, contributed to a turn in

attention towards a twentieth-century tradition of Western European

Marxist cultural critique in such figures as Gramsci, Benjamin, Adorno, and

Althusser. For Jameson in particular, this turn is said to have been

necessitated by the lack, in Douglas Kellner’s words, ‘of a tradition at hand

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

c.b. macpherson, samuel hearne, and theory 831

which could be brought to bear on its [the New Left’s] cultural concerns,

or which could politically mobilize it or offer models of radical self-

identification’ (9) – as well as by a desire to disrupt established modes of

thinking in English by a style and syntax of thought foreign to it (Homer,

14-16).2

Significantly, Spivak’s endnote invites readers to look into Macpherson

if they want ‘a “straight” analysis of the roots and ramifications of English

“individualism”’ (‘Three Woman’s Texts’ 260). Spivak apparently means

that the analysis is not filtered through her own triumvirate of continental

theory of Marxism, psychoanalysis, and deconstruction, and belongs rather

within the mainstream of Anglo-American scholarship. Macpherson’s

interlocutors, however, recognized his affinities with Marxism,3 albeit a

Marxism cast in an interestingly displaced vocabulary: he did the Marxists

in different voices.4 Undoubtedly Spivak’s ‘straight’ also signals that

Macpherson’s work is comprehensible and seemingly perspicuous –

another version of Berlin’s ‘rational and lucid,’ although from a theorist

and an era that have become more suspicious of these values. But if

continental theory has had a productively bent or estranging influence on

the empiricist, positivistic modes of thought that continue to dominate in

the English language, by passing over Macpherson we risk missing the

stranger within – one whose critical practice may be all the more disruptive

for appearing so ‘lucid’ and familiar as to be unnoticeable. Furthermore,

one risks missing the important parallels between Macpherson’s work and

these strands of continental theory, particularly the Freudian Marxism and

proto-deconstruction of the Frankfurt School.5

Macpherson described the careful, rigorously close, dialectical reading

he performed upon the tradition of political theory in the English language

from Hobbes and Locke in the seventeenth century to Isaiah Berlin and

2 The lack of familiarity with Macpherson’s work, or the failure to note him in this context,

is remarkable. Michael Ryan’s Marxism and Deconstruction, a work that early on attempted

both to trace the affinities of these two modes of critique and to demonstrate how they

might productively supplement each other, devotes some six pages of the introduction to

outlining a deconstruction of Hobbes. Macpherson’s central concept of ‘possessive

individualism’ is employed by Ryan (2), and his point that Hobbes ‘cloaks class interests

in the assumption of universal reason’ (3) very much recalls Macpherson’s reading of

Hobbes, yet Macpherson is nowhere cited.

3 See Svacek for an excellent treatment of the question of Macpherson’s Marxism. As Svacek

comments: ‘there is a nearly uniform concern among Macpherson’s critical commentators

either to mask or unmask him as a Marxist’ (395). For many liberal critics of the Cold War

years, to label Macpherson a Marxist was sufficient for dismissing his ideas.

4 Townsend comments suggestively on the displaced Marxist vocabulary in Macpherson’s

work and the possible strategies involved in choosing to employ such a vocabulary (12).

5 The figures associated with this school, most centrally Benjamin and Adorno, have been

intensively engaged by Anglo-American criticism and theory over the last three decades

and I thus treat them as ‘contemporary.’

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

832 adam carter

Milton Friedman in the twentieth century as ‘Essays in Retrieval’ – essays

aimed at determining and separating out what was, for the purposes of the

emancipation of greater numbers of people, useful, insightful, and

progressive in this theoretical tradition from what was outmoded, deluded,

contradiction-ridden, even deceptive and dominating. Like Townsend, I

would suggest that contemporary literary and cultural criticism and theory

would benefit from ‘Retrieving Macpherson’ (Townsend, 189) – encounter-

ing and engaging Macpherson’s critical practice and considering its

anticipations of and parallels and general relevance to our current concerns

and practices.6 To begin retrieving Macpherson I need first to outline the

argument of his major study, The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism.

I want to draw out his productively dialectical reading of individualism

and to suggest its parallels with the thought of Theodor Adorno and to

consider Macpherson’s problematic of possessive individualism in relation

to a passage of a text that has been of greater concern to literary scholars

and historians: Samuel Hearne’s A Journey to the Northern Ocean.

ii

Macpherson was once described as being ‘five-sixths of a Marxist’ (Svacek,

419), and his The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism, published in

1962, is indeed a broadly Marxist critique of seventeenth-century English

political theory. The work challenged the mainstream of Anglo-American

scholarship in political theory (then and now) in arguing that the origins

of contemporary liberal democratic theory, in John Locke and others, are

indelibly tied to the emergent capitalism – ‘possessive market society’ in

Macpherson’s displaced Marxist vocabulary – of the seventeenth century.

Macpherson’s central argument is that underlying and informing the

political theories of Thomas Hobbes, the Levellers, James Harrington, and

John Locke – theories that had traditionally been interpreted as running the

gamut from authoritarianism through liberalism to proto-socialism–is a

shared and unquestioned assumption concerning the nature of the

individual. This conception of the individual unifies the apparently diverse

theories of the seventeenth century within the closure of an ideological

horizon and, at times, even subverts or defeats the potentially democratic

impulses of certain of these statements. In Fredric Jameson’s terminology,

this concept forms the basic, shared ‘ideologeme’ (76, 87–88), a fundamen-

6 A fuller consideration of this topic would also need to consider how Macpherson’s

practice and its underlying assumptions conflict with our contemporary assumptions and

concerns and what we might learn from such conflicts. While I touch on these issues here

in examining and defending Macpherson’s dialectical approach to liberal individualism,

I plan to treat such conflicts, or differences, at greater length in a separate essay devoted

to Macpherson’s critical method in relation to Adorno’s negative dialectics and Derrida’s

deconstruction.

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

c.b. macpherson, samuel hearne, and theory 833

tal unit of thought that is at the same time ideological, beyond which no

thinking penetrates. Furthermore, this conception of the individual

provides the central difficulty for the tradition of democratic theory that

has attempted to build upon the seventeenth-century basis.

The central difficulty in the concept of the individual in seventeenth-

century political theory, Macpherson argues, lies in its ‘possessive quality’

(Political Theory, 3). In a passage worth quoting at length, he puts very

forcefully both his conception of ‘possessive individualism’ and the

concomitant view of society that this assumption entails:

[The] possessive quality [of seventeenth-century individualism] is found in its

conception of the individual as essentially the proprietor of his own person or

capacities, owing nothing to society for them. The individual was seen neither as

a moral whole, nor as part of a larger social whole, but as an owner of himself. The

relations of ownership, having become for more and more men the critically

important relation determining their actual freedom and actual prospect of

realizing their full potentialities, was read back in to the nature of the individual.

The individual, it was thought, is free inasmuch as he is proprietor of his person

and capacities. The human essence is freedom from dependence of the wills of

others, and freedom is a function of possession. Society becomes a lot of free

equal individuals related to each other as proprietors of their own capacities and

of what they have acquired by their exercise. Society consists of relations of

exchange between proprietors. Political society becomes a calculated device for

the protection of this property and for the maintenance of an orderly relation of

exchange. (3; emphasis added)7

In keeping with a tradition of Marxist and related forms of critique,

what Macpherson argues throughout the work is that the social, historical

characteristics of the individual within a possessive market economy are

universalized, or ontologized, as being naturally characteristic of individu-

als as such. As Macpherson succinctly put his argument in ‘The Deceptive

Task of Political Theory,’ first published in 1954: ‘The limit of bourgeois

vision with respect to political theory lay ... in the assumption that bour-

geois human nature is the final form (or, more usually, the universal form

except for some supposed primitive age) of human nature’ (Democratic,

198).

Although he rarely used the terms, the interrelated concepts of com-

modity fetishism and reification are, as commentators like William Leiss

7 We have here the antinomy of T.S. Eliot’s characterization of seventeenth-century England

as an organic society – a characterization still influential when Macpherson’s study was

published, which might partly explain why Macpherson would not serve as an influential

intellectual historian like A.O. Lovejoy for the main line of literary scholars of the mid-

twentieth century.

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

834 adam carter

(58–59) and Jules Townsend (19) have noted, at the root of Macpherson’s

theorization and critique of possessive individualism. These concepts were

first outlined by Marx but were more elaborately developed by Lukács,

with notable and lasting influence on theorists such as Adorno and

Jameson. Lukács built upon Marx to suggest that – with the increasingly

complex and fragmenting division of labour under capitalism, and the

increasing reduction of social relations to abstract, distanced economic

relations of exchange – the individual was increasingly incapable of

grasping the totality of social relations, of grasping his or her fragmented

world as social process and social relation between humans. The world

appears, rather, as pre-made, a world of disassociated things that the

subject stands outside of and confronts as an object (Lukács, 83–149).

Macpherson’s central thrust was to argue how such a reified world-view

was ‘read back into the nature of the individual,’ so that the individual

human being comes to be seen as an isolated thing – and, more to the point,

a commodity to be bought and sold on the market. I am my own property,

a least common denominator of ownership justifying all other property

relations. If, with Descartes, modern philosophy seeks a stable origin in the

presence of a self-conscious cogito, then modern political theory, Macpher-

son argues, posits its origin to be self-ownership.8 A ‘subject-effect’ of

capitalist social relations is substituted as origin or cause of such relations.

With his suggestive reference to the act of reading in the formation of the

subject, Macpherson subtly draws attention to the kind of rhetorical

metalepsis that has engaged deconstructive critics in more recent years in

their own critique of the subject.9

Let me draw briefly two further parallels between Macpherson’s

concerns and those of other twentieth-century continental theorists who

have played a more central role in contemporary theory: Roland Barthes’s

essays from the 1950s, collected in Mythologies, offer a familiar, somewhat

parallel, argument about how ideology naturalizes or ontologizes the

historical to serve particular ideological ends; Adorno’s critique of the

German philosophical tradition up to and including Heidegger is in places

even more strikingly parallel to Macpherson’s concern with possessive

individualism and, more generally, with how the logic and rhetoric of the

xxxxxxx

8 The existentialist problematic of Heidegger and Sartre engages in a somewhat parallel

critique of the inauthenticity of equating Being with the thing-like characteristics of objects

in nature. Through Paul de Man such a problematic becomes influential for literary theory

and is later transformed, through a linguistic turn, into a critique of identifying the

linguistic and empirical selves, of reading the one back into the other (Blindness, 216).

9 Spivak provides a good summary of the ‘subject-effect’ as metalepsis in ‘Deconstructing

Historiography’ (213). The work of Judith Butler has influentially continued such

investigations. See her Psychic Life of Power, particularly the chapter on Louis Althusser

(106–31).

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

c.b. macpherson, samuel hearne, and theory 835

capitalist market pervades thinking. In The Jargon of Authenticity, for

example, Adorno critiques Heidegger’s conception of the ‘mineness’ of

Dasein for unwittingly rehearsing the very logic of capitalist property

relations which Heidegger’s philosophy seeks to escape. ‘The jargon [of

authenticity, i.e., the existentialist philosophy of Heidegger and his

followers] cures Dasein from the wound of meaninglessness and summons

salvation from the world of ideas into Dasein. Heidegger lays this down

once and for all in the title deed, which declares that the person own himself

... The subject, the concept of which was once created in contrast to

reification, thus becomes reified’ (Jargon, 114–15; emphasis added). Further-

more, in a footnote to Negative Dialectics, Adorno hits passingly upon

Macpherson’s central thesis in critically engaging throughout his career the

tradition of English, social-contract theory: ‘The imaginary social contract,’

Adorno maintains, ‘was so welcome to the early bourgeois thinkers

because its fundament, its formal legal a priori, was the barter relationship

of bourgeois rationality’ (321).

In a rigorously dialectical fashion, Macpherson maintains that posses-

sive individualism is simultaneously true and untrue – albeit a dialectics

not, by the standards of contemporary critical theory and the figures that

it has retrieved, elaborately thematized or stylized. Because Macpherson’s

prose appears so lucid, one must remain all the more carefully attuned to

the text to perceive its turns of dialectic thought. Thus in demonstrating

Macpherson’s dialectical working through of possessive individualism I

will make the parallels with Adorno explicit by quoting the latter in

conjunction with Macpherson.

Possessive individualism is a valid concept, according to Macpherson,

insofar as it provides an accurate depiction of the individual’s real relations

within a capitalist society, which operates to a great extent as a vast market-

place where the individual will be defined by property relations and where

he or she must act, and will function, as property to be bought and sold.

‘However much he may wish it to be otherwise,’ Macpherson writes, ‘his

humanity does depend on his freedom from any but self-interested

contractual relations with others. His society does consist of a series of

market relations ... the assumptions are factually accurate’ (Political, 275).

Likewise, Adorno asserts, echoing Marx in the German Ideology, that ‘if the

standard structure of society is the exchange form, its rationality constitutes

people: what they are for themselves, what they think they are, is second-

ary’ (‘Subject,’ 248). Hegel’s philosophy, Adorno argues in Negative

Dialectics, is guided by ‘the picture of the individual in individualist

society’ (343), a picture which within its historic context ‘is adequate,

because the principle of the barter society was realized only through the

individuation of the several contracting parties – because, in other words

the principium individuationis literally was the principle of that society, its

universal’ (343).

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

836 adam carter

Yet for Macpherson such possessive individualism is not valid in so far

as it provides a limited, even deceptive, view of what it means to be an

individual. As Joseph Carens has succinctly put it, the limitations for

Macpherson are twofold:

First it generates an impoverished view of life, making acquisition and

consumption central and obscuring deeper human purposes and capacities ...

Second, possessive individualism holds out a false promise. Most people cannot

really enjoy even the impoverished individuality, freedom, and equality that

possessive individualism ostensibly offers to all, because a system based on

private property and so called free exchange inevitably generates a concentra-

tion of ownership of all the means of production except labor. Most people are

compelled to sell their labor to gain access to the means of life. They are free and

equal individuals in name only ... (3)

To the two central deficiencies in possessive individualism should be

added at least a third, which is that the individual is not seen therein ‘as

part of a larger social whole’ (Macpherson, Political, 3) but, rather, owes

‘nothing to society’ (3) for his or her capacities: in other words, its denial of

the communal basis of the individual.10 Adorno concurs that individualism

and freedom are, simultaneously, deceptive ideologies in capitalist society.

Again of Hegel’s philosophy he asserts that its guiding ‘picture’ of ‘the

individual in individualist society ... is inadequate because, in the total

functional context which requires the form of individuation, individuals

are relegated to the role of mere executive organs of the universal’ (Nega-

tive, 343): they are free in name only; in actuality they are subordinated

functions within the rigorously structured and hierarchical totality of

society.

But in a further moment of dialectical reversal and sublation, Macpher-

son maintains that possessive individualism contains, negatively, the seeds

of a more utopian truth. Liberal individualism’s conception of being one’s

own possession, and in this respect being fundamentally equal to others,

opens up genuine possibilities of freedom, creativity, and fulfilment that

potentially mark an advance over the hierarchical and static social

structures of the past. In this respect Macpherson could even champion the

progressive elements in the otherwise authoritarian politics of Thomas

Hobbes. Macpherson’s position again parallels Adorno, who regarded the

notions of equivalence produced by ‘barter society’ as ‘ideology but also

promise’ (Negative, 146) and who, in confronting the theoretical urge to

10 As Townsend notes (138–40), though critiqued by communitarian theorists such as

Alasdair MacIntyre for remaining too individualistic in his theory, Macpherson was

clearly critical of the asocial definition of the individual within the main line of liberal

political theory.

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

c.b. macpherson, samuel hearne, and theory 837

dismantle the subject represented by both scientific positivism and

Heideggerian existentialism, warned: ‘Were it [i.e., the subject] liquidated

instead of sublated into a higher form, the result would be not merely a

regression of consciousness but a regression to real barbarism’ (‘Subject,’

247).

Any pretension, however, that the utopian seeds of individualism could

be realized within the property relations of a possessive market economy,

where the great majority of individuals possess neither the leisure nor the

material means for creative self development, is ideological deception

(Macpherson, Democratic, 24–38). Macpherson went so far as to suggest that

the mainstream of liberal political thought from John Stuart Mill to the

twentieth century had been, however consciously or unconsciously, largely

engaged in such a ‘deceptive task’ (Democratic, 195–203). Again the

parallels with Adorno here are striking. Of the elevation of the subject

within the tradition of German idealist philosophy Adorno argued: ‘The

ideological function of the thesis cannot be overlooked. The more

individuals are in effect degraded into functions within the societal totality

as they are connected up to the system, the more the person pure and

simple, and as a principle, is consoled and exalted with the attributes of

creative power, absolute rule, and spirit’ (‘Subject,’ 248). Thus the utopian

element of individualism must be regarded as untrue, insofar as it might

purport to give a ‘factually accurate’ depiction of the possibilities character-

izing current social and economic organization. The recognition of this

falsity, however, may stand in a productively critical relationship to the

current social economic order as a recognition of the potentialities it does

not allow.

What never seems to have been contemplated in the commentary on

Macpherson, much less worked through in critical studies that might take

up and extend his legacy, is just how thoroughly in his view such a reified

conception of the individual as property penetrated not only the legal-

juridical definition of the individual but also the very understanding of

what it means to be human. The inability to grasp this extent may partially

be attributable to the fact that while, as William Leiss has observed,

possessive individualism centrally informed much of Macpherson’s theory,

he never provided a particularly sustained analysis of the concept (44).Yet

references in various parts of Macpherson’s work tantalizingly suggest just

how far down he thought the assumptions of possessive individualism

might go. In arguing, in The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism, that

the seventeenth-century Levellers, who had generally been read, prior to

Macpherson, as supporters of a universal franchise, in fact shared the same

limiting possessive individualist conceptions as their political opponents,

Macpherson asserts that for the Levellers ‘it is this property [one’s owner-

ship of one’s self], this exclusion of others, that makes a man human’ (142;

emphasis added). In the concluding chapter of the same work Macpherson

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

838 adam carter

twice repeats, italicizing the predicate for emphasis, that the ‘individual in

a possessive market society is human in his capacity as proprietor of his

own person’ (271, 275). In Democratic Theory, a later collection of essays,

Macpherson likewise suggests that the seventeenth-century political

writers ‘did not think of the propertyless labouring classes as fully human,

or at least not as full citizens’ (28).

The alternative that Macpherson provides in this last example is not

insignificant; there is potentially a considerable difference between not

being a full citizen and not being fully human. Macpherson’s hesitancy

here may point to a genuine and non-dogmatic uncertainty with respect to

just how deeply the assumptions of possessive individualism penetrate.

Just far enough down to deny others the vote, and thus full participation

in civil society? Or far enough down to conceive of others as less than, or

other than, human? Nonetheless, the way these references provide ample

evidence that he believed the assumptions of possessive individualism

might go very far down indeed suggests that his thought might produc-

tively be placed in relation with a body of more recent poststructuralist and

postcolonial theory and criticism that has variously been concerned with

the construction of the human and the boundaries of the human and non-

human as defined in contexts of power and knowledge.11

In drawing this essay to a conclusion I would like to gesture towards

making such a relation by briefly attempting a reading of a passage of a

text that has engaged literary critics, particularly in Canada. This brief

analysis might begin to show some of the directions and possibilities

opened up by Macpherson’s problematic. That the reading might not

appear unfamiliar within the current ethos of literary criticism perhaps

further suggests that Macpherson’s concerns are current ones. And while

Macpherson’s own theory does not directly address such key contempo-

rary issues such as race, colonialism, and postcolonialism, this example

suggests how his work might be brought into a productive dialogue with

such concerns. At the same time, to read for the assumptions of possessive

individualism within more broadly cultural texts promises to advance

Macpherson’s own goals insofar as such a reading might begin to address

the question implicitly posed by Macpherson: How far do the assumptions

of possessive individualism permeate thinking in English and European

thought of the last four centuries?

iii

The passage I wish to consider, from Samuel Hearne’s late eighteenth-

century exploration narrative A Journey From Prince of Wales’s Fort in

11 For an exemplary exploration, from a poststructuralist perspective, of the limits of the

human within the context of power and knowledge, see Clark and Myser.

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

c.b. macpherson, samuel hearne, and theory 839

Hudson’s Bay to the Northern Ocean, is part of the infamous narration of the

ambush and slaughter of a group of Inuit by the Chipewyans with whom

Hearne travelled. In fascinatingly ambiguous and contradictory ways

Hearne is constructed within the text as an innocent bystander to these

events, one who morally condemns the attack and refuses active participa-

tion in it, yet who is at the same time compelled in the interests of his own

life to accompany the group and to witness the massacre. While the author-

ship and historical veracity of this part of the narrative are uncertain – it

being the practice of publishers of that period to supplement and embellish

exploration narratives in the interests of brisker sales (MacLaren, ‘Massa-

cre’) – such questions need not detain us, as I am concerned with broadly

shared cultural assumptions.

Throughout Hearne’s exploration narrative, an understated but per-

sistent question the text returns to are the limits and boundaries not only

of civilization and barbarism but of the human and the inhuman, and the

extent to which the European can judge the Native to be human.12 The

position of an earlier generation of historians and literary scholars, such as

Maurice Hodgson – namely, that Hearne in several instances sympatheti-

cally and sensitively upholds the underlying humanity of the Native

peoples – often strikes the reader as valid. Thus, for example, Hearne

contextualizes a practice such as cannibalism both by noting that it is only

practised under the most acutely life-threatening conditions and by

emphasizing that anyone who has engaged in the practice is thereafter

shunned by the others for having transgressed the most basic of social

prohibitions (22). In contrast, in the context of the Inuit slaughter Hearne’s

rhetoric tends towards description of the Natives as ‘bloody’ (96, 99),

‘barbaric’ (99), ‘brutish’ (100), ‘savage’ (100) and ‘inhuman’ (74).

Manifestly, this judgment derives from a moral condemnation of what

is judged to be unwarranted violence perpetrated by the Chipewyans upon

the Inuit. But in Hearne’s intricate descriptions of his party’s preparations

for the attack which, as I.S. MacLaren has pointed out, function as skilful

tactics in narrative delay to build suspense (‘Landscapes’ 33), Hearne

makes a suggestive reference not to morally condemnable behaviour but

to the simultaneous breakdown in both individuality and private property

among the war party he accompanies.

It is perhaps worth remarking, that my crew, though an undisciplined rabble,

and by no means accustomed to war or command, seemingly acted on this

horrid occasion with the utmost uniformity of sentiment. There was not among

them the least altercation or separate opinion; all were united in the general

cause, and as ready to follow where Matonabbee led, as he appeared to be ready

12 An informative overview of, and contribution to, the critical interpretations of this

question is provided by Hutchings.

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

840 adam carter

to lead ... Never was reciprocity of interest more generally regarded among a

number of people, than it was on the present occasion by my crew, for not one

was a moment in want of any thing that another could spare; and if ever the

spirit of disinterested friendship expanded the heart of a Northern Indian, it was

here exhibited in the most extensive meaning of the word. Property of every kind

that could be of general use now ceased to be private, and every one who had any

thing which came under the description, seemed proud of an opportunity of

giving it, or lending it to those who had none, or were most in want of it.

(97–98; emphasis added)

What is happening here? The passage evokes a poignant paradox of the

kind that recurs in the literature of the West from the Iliad to those

contemporary Hollywood films that narrate the horrors and the heroism

of America’s involvement in two centuries of war. According to this

paradox we are most ‘human’ – as in the most communal, loving,

sacrificing of ourselves, and giving towards others – at the moment of our

greatest ‘inhumanity,’ our violent, even senseless, destruction of others.

Using Macpherson’s terms of analysis, however, another reading

suggests itself. We become attuned to the conflation in the text of the loss

of individuality, the collapse of private property, and the group’s ‘inhuman

design’ (Hearne, 74). In this reading, the text, in a manner that is doubtless

less than fully conscious, compellingly articulates and reads back into

Native peoples the concept of ‘possessive individualism,’ the view that, as

Macpherson writes, ‘the individual is human in his capacity as proprietor

of his own person’ (Political, 271), and thus, whatever the deceptive

appearances of sociality might suggest to the contrary, inhuman to the

extent that such self-propriety and the private property that stems from it

break down. Hearne’s reference to the group’s ‘inhuman design’ becomes

not merely a figure of speech for morally reprehensible violence but a

suggestion also that the divestment of private property is in fact commen-

surate with the divestment of individuality and humanity. In one of the

several instances in the text in which he exonerates himself from blame in

the massacre, Hearne insists that it would have been ‘the highest folly for

an individual like me, and in my situation, to attempt to turn the current of

a national prejudice which had subsisted between those two nations from

the earliest periods, or at least as long as they had been acquainted with the

existence of each other’ (75; emphasis added). One senses here, in addition

to Hearne’s prudent recognition of the potential folly of one person

speaking out against the will of the many, the hint that it is precisely his

individualism, anchored in his self-possession, that rescues him from

partaking in the barbaric actions of the herd.

In this representation of the massacre the loss of individuality and

humanity is thus intricately associated with the divestment of private

property. To represent such a loss, however, is to suggest that the Natives

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

c.b. macpherson, samuel hearne, and theory 841

do hold a concept of private property – ‘property ... now ceased to be

private’ (98). That is, the text suggests in some respects that private

property is natural to Native peoples – just as Locke, as Macpherson notes,

posits private property as existing in a state of nature, albeit vulnerable to

appropriation by others and thus in need of stable political and judicial

authority to protect it (Political, 197–203). One might see, therefore, the

familiar logic of empire operating within the text, which asserts that the

Natives have a capacity to be human, as exhibited in their crude concep-

tions of private property, but simultaneously asserts their capacity to be

inhuman in their loss of such a conception. By the terms of such a logic, to

develop this tenuous sense of private property so that it will be less readily

given up will be to develop individuality, reasonableness, and humanity.13

What is lacking, therefore, is a fully developed possessive market economy,

a lack that Hearne, as an agent of the Hudson’s Bay Company, of explora-

tion and trade, exists in part to fill.

Thus by reading Hearne through Macpherson, the narration of the

massacre becomes an allegory of self-possession and self-dispossession in

the context of the expansion of a European market and its property

relations. That the representation of the massacre should contain the single

most powerful instance in the narrative of the figure of Hearne himself –

the description of his almost losing his own self-possession as a dying Inuit

girl entwines herself around his leg – attests to the stakes involved here.

‘My situation and the terror of my mind at beholding this butchery, cannot

easily be conceived, much less described; though I summoned up all the

fortitude I was master of on the occasion, it was with difficulty that I could

refrain from tears’ (100). As MacLaren has also observed, the aesthetics of

the sublime are central to the representation of the Inuit massacre (‘Land-

scapes,’ 30–34), which tantalizingly suggests the possibility of reading the

interconnections of the sublime, the divestment of property, and the

potential loss of self-possession, a threat that, if successfully mastered,

stands as the strongest possible affirmation of the individual and his self-

possession.14

iv

In his own contribution to the various efforts over the last two decades to

retrieve Adorno for contemporary criticism and theory, Fredric Jameson

has suggested that among other things, Adorno’s work could allow an

13 Perhaps the most pertinent form of such a logic in this context was the theory of the four

stages of civilization prevalent in the ethnography of the time whereby civilizations were

believed to progress from the depths of savagery to the heights of commercial society (see

MacLaren, ‘Massacre,’ 39–40).

14 For a reading of eighteenth-century theories of the sublime that ties aesthetic theory into

individuation, see Ferguson.

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

842 adam carter

understanding and critique of the operations of ‘Capital-logic’ (Late Marx-

ism, 239) – how the underlying structure of capitalist exchange society

comes to be intricately entwined with our most basic thinking on funda-

mental issues such as human equality and identity (Late Marxism, 239–41).

Such a critique, Jameson suggests, is indispensable to criticism in the

postmodern era of global capitalism because such a logic penetrates ever

more deeply and pervasively. Other reconsiderations of the Frankfurt

School theorists, notably that undertaken by Peter Dews, have emphasized

how their theory might provide a politicized deconstruction, one that,

while subjecting the values of an Enlightenment tradition such as reason,

liberty, and individualism to a thoroughgoing immanent critique, redeems

such values rather than dispenses with them. The retrieval of Macpherson’s

work holds similar potential. A study of ‘Capital-logic,’ specifically how

property relations and the commodity form have infiltrated and structured

the understanding of what it means to be an individual, even what it

means to be human, is compellingly pursued in his writing. Alongside this

central theme are other tantalizing insights, such as his suggestion that in

Locke the very structure of reason comes to be equated with the industri-

ous appropriation of a possessive market society. Any continuation of such

a project of comprehending and critiquing the logic and rhetoric of capital

could be enriched by an extended engagement with the insights and the

exemplary critical model his work provides.

Critical models taken from the Frankfurt School and deconstruction

have necessarily entailed an engagement with continental philosophy and

an adoption of its often dense vocabularies. Macpherson’s work demon-

strates compellingly the extent to which criticism can penetrate its object

without departing from a relatively normative Anglo-American academic

vocabulary and structure of argument. As critical vocabularies continue to

proliferate, it is worthwhile to hold on to this lesson as a counterbalance to

the more generally acknowledged suggestion that no such apparently

normative vocabulary and structure of argument can be taken as natural

or absolute. Indeed, Macpherson’s criticism may be all the more immanent

and disruptive for moving with such apparent ease within the structures

and values it seeks to critique.

WORKS CITED

Adorno, Theodor. The Jargon of Authenticity. Trans Knut Tarnowski and Frederic

Will. Evanston: Northwestern University Press 1973

– Negative Dialectics. 1966. Trans E.B. Ashton. New York: Continuum 1973

– ‘On Subject and Object.’ Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords. Trans

Henry Pickford. New York: Columbia University Press 1998, 245–58

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Trans Annette Lavers. London: Paladin 1973

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

c.b. macpherson, samuel hearne, and theory 843

Butler, Judith. The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection. Stanford: Stanford

University Press 1997

Carens, Joseph. ‘Possessive Individualism and Democratic Theory: Macpherson’s

Legacy.’ Democracy and Possessive Individualism: The Intellectual Legacy of C.B.

Macpherson. Ed Joseph Carens. Buffalo: suny Press 1993

Clark, David L., and Catherine Myser. ‘Being Humaned: Medical Documentaries

and the Hyperrealization of Conjoined Twins.’ Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the

Extraordinary Body. Ed Rosemarie Garland Thomson. New York: New York

University Press 1996, 338–55

Culler, Jonathan. On Deconstruction: Theory and Criticism after Structuralism. Ithaca:

Cornell University Press 1982

de Man, Paul. Blindness and Insight: Essays in the Rhetoric of Contemporary Criticism.

2nd ed, rev. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 1983

Dews, Peter. The Logics of Disintegration: Post-Structuralist Thought and the Claims of

Critical Theory. London: Verso 1987

Eagleton, Terry. The Ideology of the Aesthetic. Oxford: Blackwell 1990

– Walter Benjamin: or Towards a Revolutionary Criticism. London: Verso 1981

Ferguson, Frances. Solitude and the Sublime: Romanticism and the Aesthetics of Indi-

viduation. New York: Routledge 1992

Greenblatt, Stephen. Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press 1980

Hartman, Geoffrey. ‘Tea and Totality: The Demand of Theory on Critical Style.’

Contemporary Critical Theory. Ed Dan Latimer. San Diego: Harcourt 1989, 236–52

Hearne, Samuel. A Journey From Prince of Wales’s Fort in Hudson’s Bay to the Northern

Ocean. Ed Richard Glover. Toronto: Macmillan 1958

Hodgson, Maurice. ‘The Exploration Journal as Literature.’ Beaver 298 (Winter

1967), 4–12.

Homer, Sean. Fredric Jameson: Marxism, Hermeneutics, Postmodernism. New York:

Routledge 1998

Hutchings, Kevin. ‘Writing Commerce and Cultural Progress in Samuel Hearne’s

A Journey ... to the Northern Ocean.’ Ariel 28:2 (1997), 49–78

Jameson, Fredric. Late Marxism: Adorno, or, The Persistence of the Dialectic. London:

Verso 1990

– The Political Unconscious. Ithaca: Cornell University Press 1981

Kellner, Douglas. Postmodernism, Jameson, Critique. Washington: Maisonneuve 1989

Leiss, William. C.B. Macpherson: Dilemmas of Liberalism and Socialism. Montreal: New

World Perspective 1988

Lukács, Georg. History and Class Consciousness. Trans Rodney Livingstone. London:

Merlin 1971

MacLaren, I.S. ‘Samuel Hearne and the Landscapes of Discovery.’ Canadian

Literature 103 (1984), 27–40

– ‘Samuel Hearne’s Accounts of the Massacre at Bloody Fall, 17 July 1771.’ Ariel

22:1 (1991), 25–51

Macpherson, C.B. Burke. New York: Hill and Wang 1980

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

844 adam carter

– Democratic Theory: Essays in Retrieval. Oxford: Clarendon 1973

– The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke. Oxford: Clarendon

1962

Mitchell, W.J.T. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

1986

Ryan, Michael. Marxism and Deconstruction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Press 1982

Simpson, David. Romanticism, Nationalism, and the Revolt against Theory. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press 1993

Spivak, Gayatri. ‘Deconstructing Historiography.’ The Spivak Reader. Ed Donna

Landry and Gerald MacLean. New York: Routledge 1996

– ‘Three Woman’s Texts and a Critique of Imperialism.’ Critical Inquiry 12:1 (1985),

243–61

Svacek, Victor. ‘The Elusive Marxism of C.B. Macpherson.’ Canadian Journal of

Political Science 9:3 (1976), 395-422

Taylor, Charles. Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Cambridge, ma:

Harvard University Press 1989

Townsend, Jules. C.B. Macpherson and the Problem of Liberal Democracy. Edinburgh:

Edinburgh University Press 2000

Tully, James. ‘The Possessive Individualism Thesis: A Reconsideration in Light of

Recent Scholarship.’ Democracy and Possessive Individualism: The Intellectual Legacy

of C.B. Macpherson. Ed Joseph Carens. Buffalo: suny Press 1993, 19–44

university of toronto quarterly, volume 74, number 3, summer 2005

You might also like

- Marx On Emancipation & Socialist Goals: Retrieving Marx For The FutureDocument266 pagesMarx On Emancipation & Socialist Goals: Retrieving Marx For The FutureromulolelisNo ratings yet

- Sayer, Derek and Philip Corrigan - Revolution Against The State, The Context and Significance of Marx's Later WritingsDocument18 pagesSayer, Derek and Philip Corrigan - Revolution Against The State, The Context and Significance of Marx's Later WritingsMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Method/TheoryDocument2 pagesMethod/TheoryDanielRamirezNo ratings yet

- Adamson, Walter L. 1981 'Marx's Four Histories - An Approach To His Intellectual Development ' History & Theory, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Dec., Pp. 379 - 402)Document25 pagesAdamson, Walter L. 1981 'Marx's Four Histories - An Approach To His Intellectual Development ' History & Theory, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Dec., Pp. 379 - 402)voxpop88No ratings yet

- Marx's Life, Works, and Legacy ExploredDocument8 pagesMarx's Life, Works, and Legacy ExploredDiego MartínezNo ratings yet

- Rediscovering LeninDocument212 pagesRediscovering Leninkayraadam913No ratings yet

- Ernst Cassirer and The Critical Science of Germany, 1899-1919Document2 pagesErnst Cassirer and The Critical Science of Germany, 1899-1919Antonie de ManNo ratings yet

- MARXIST LITERARY CRITICISM: WHAT IT IS NOTDocument9 pagesMARXIST LITERARY CRITICISM: WHAT IT IS NOTSukriti GudiyaNo ratings yet

- Louis Althusser, Ben Brewster - For Marx (1985, Verso)Document242 pagesLouis Althusser, Ben Brewster - For Marx (1985, Verso)Fabio BrunettoNo ratings yet

- Marxism and Modernism: An Historical Study of Lukacs, Brecht, Benjamin, and AdornoFrom EverandMarxism and Modernism: An Historical Study of Lukacs, Brecht, Benjamin, and AdornoRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)

- SSRN Id3578840Document71 pagesSSRN Id3578840Jean Pierre Sauré RoeckelNo ratings yet

- Katz, Barry (1982) - Herbert Marcuse and The Art of Liberation. An Intellectual BiographyDocument230 pagesKatz, Barry (1982) - Herbert Marcuse and The Art of Liberation. An Intellectual BiographyLeandro Sánchez MarínNo ratings yet

- H. P. Lovecraft and His Science Fiction-Horror: Tamkang UniversityDocument26 pagesH. P. Lovecraft and His Science Fiction-Horror: Tamkang UniversityJuani RoldánNo ratings yet

- Karl Marx's Life, Ideas, and InfluencesDocument392 pagesKarl Marx's Life, Ideas, and InfluencesJohn100% (4)

- Mach Musil and ModernismDocument19 pagesMach Musil and ModernismCrisisDeLaPresenciaNo ratings yet

- The African American Philosopher McClendonDocument40 pagesThe African American Philosopher McClendonAsanijNo ratings yet

- George C Comninel Alienation and Emancipation in The Work of Karl Marx PDFDocument358 pagesGeorge C Comninel Alienation and Emancipation in The Work of Karl Marx PDFalexandrospatramanisNo ratings yet

- 1 Introduction: Marx, Ethics and Ethical MarxismDocument39 pages1 Introduction: Marx, Ethics and Ethical MarxismbaclayonNo ratings yet

- Oxford Handbooks Online: Karl Marx and British SocialismDocument17 pagesOxford Handbooks Online: Karl Marx and British SocialismOmar Sánchez SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Karl Marx on Society and Social Change: With Selections by Friedrich EngelsFrom EverandKarl Marx on Society and Social Change: With Selections by Friedrich EngelsNo ratings yet

- Bakhtin and Medieval VoicesDocument196 pagesBakhtin and Medieval Voicesquartzz0% (1)

- Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of The Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max WeberDocument141 pagesCapitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of The Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber徐松100% (3)

- Dic MarxDocument230 pagesDic Marxhaoying zhangNo ratings yet

- Recent Studies in The English RenaissanceDocument37 pagesRecent Studies in The English RenaissancemirnafarahatNo ratings yet

- The Practice of Satire in England, 1658-1770, by Ashley MarshallDocument4 pagesThe Practice of Satire in England, 1658-1770, by Ashley MarshallRita ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- The Phenomenology of The Anti-Spirit": Adorno's Marxism As Critical TheoryDocument8 pagesThe Phenomenology of The Anti-Spirit": Adorno's Marxism As Critical TheoryEsparzaNo ratings yet

- The Study of Elites in Late AntiquityDocument27 pagesThe Study of Elites in Late AntiquityRadosław DomazetNo ratings yet

- C Wright Mills The Sociological Imagination and TDocument17 pagesC Wright Mills The Sociological Imagination and TscribdNo ratings yet

- (Marx, Engels, and Marxisms) Ranabir Samaddar (Auth.) - Karl Marx and The Postcolonial Age-Palgrave Macmillan (2018)Document328 pages(Marx, Engels, and Marxisms) Ranabir Samaddar (Auth.) - Karl Marx and The Postcolonial Age-Palgrave Macmillan (2018)JOSÉ MANUEL MEJÍA VILLENANo ratings yet

- The Fate of "the Sociology of LiteratureDocument20 pagesThe Fate of "the Sociology of LiteratureHoang Phong Tuan0% (1)

- Marxism, Ethics and Politics - The Work of Alasdair MacIntyre (Marx, Engels, and Marxisms) (PDFDrive)Document234 pagesMarxism, Ethics and Politics - The Work of Alasdair MacIntyre (Marx, Engels, and Marxisms) (PDFDrive)Papiya Bairagi100% (1)

- Warren Carter Renew Marxist Art History PDFDocument1,031 pagesWarren Carter Renew Marxist Art History PDFShaon Basu100% (3)

- Lukacs, Marx, and The Sources of Critical Theory (Feenberg, Andrew)Document308 pagesLukacs, Marx, and The Sources of Critical Theory (Feenberg, Andrew)advsouza1No ratings yet

- Understanding Marx: A Reconstruction and Critique of CapitalFrom EverandUnderstanding Marx: A Reconstruction and Critique of CapitalRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Marx's Ghost and the Development of Marxist ArchaeologyDocument3 pagesMarx's Ghost and the Development of Marxist ArchaeologyChristian MfNo ratings yet

- The Brazilian Left in the 21st Century: Conflict and Conciliation in Peripheral CapitalismFrom EverandThe Brazilian Left in the 21st Century: Conflict and Conciliation in Peripheral CapitalismVladimir PuzoneNo ratings yet

- "Post-Marxism" and The Social and Political Theory of Karl MarxDocument31 pages"Post-Marxism" and The Social and Political Theory of Karl MarxMilos JankovicNo ratings yet

- University of Pennsylvania Press Huntington Library QuarterlyDocument16 pagesUniversity of Pennsylvania Press Huntington Library QuarterlyMariana RochaNo ratings yet

- Werner Blumenberg Potrait of Marx OptimsedDocument202 pagesWerner Blumenberg Potrait of Marx OptimsedBreno PereiraNo ratings yet

- Simonson Rsa Summer InstituteDocument9 pagesSimonson Rsa Summer InstituteShruti DesaiNo ratings yet

- BALDWIN (Individual and Self in The Late Renaissance)Document24 pagesBALDWIN (Individual and Self in The Late Renaissance)pedromartinezNo ratings yet

- Robert K. Merton's Influence on SociologyDocument14 pagesRobert K. Merton's Influence on SociologyJorge Sánchez Bazán100% (2)

- Weber Stammler PDFDocument25 pagesWeber Stammler PDFGuisepp BancoNo ratings yet

- Informe de Procesador de TextosDocument12 pagesInforme de Procesador de TextosBelen Ramirez CastroNo ratings yet

- The Recovery of Western MarxismDocument3 pagesThe Recovery of Western MarxismBen RosenzweigNo ratings yet

- The Works of Marx and EngelsDocument53 pagesThe Works of Marx and EngelsSubproleNo ratings yet

- 251-262. 8. Social Context and The Failure of TheoryDocument13 pages251-262. 8. Social Context and The Failure of TheoryBaha ZaferNo ratings yet

- Gordin Kolman HSNS2017Document29 pagesGordin Kolman HSNS2017Keti ChukhrovNo ratings yet

- Marxist Literary Criticism Before Georg Lukacs: January 2016Document5 pagesMarxist Literary Criticism Before Georg Lukacs: January 2016MbongeniNo ratings yet

- 2 Marxist HistoriographyDocument16 pages2 Marxist Historiographyshiv161No ratings yet

- On the Nature of Marx's Things: Translation as NecrophilologyFrom EverandOn the Nature of Marx's Things: Translation as NecrophilologyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- William Leiss-C.B.macpherson - Dilemmas of Liberalism and Socialism-New World Perspectives (1989)Document154 pagesWilliam Leiss-C.B.macpherson - Dilemmas of Liberalism and Socialism-New World Perspectives (1989)Roxana AydinNo ratings yet

- Neil Larsen, Modernism and HegemonyDocument175 pagesNeil Larsen, Modernism and HegemonyMonica QuijanoNo ratings yet

- Friedrich Max M Ller The Career and Intellectual Trajectory of A German Philologist in Victorian BritainDocument32 pagesFriedrich Max M Ller The Career and Intellectual Trajectory of A German Philologist in Victorian BritainMateus CruzNo ratings yet

- Hullot-Kentor, R. (1992) Notes On The Dialectic of Enlightenment - Translating The Odysseus EssayDocument9 pagesHullot-Kentor, R. (1992) Notes On The Dialectic of Enlightenment - Translating The Odysseus EssayMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Yu & Tang - Thing, Value, Time, and Freedom - A Consideration of Some Key Concepts in Marx's Philosophical SystemDocument11 pagesYu & Tang - Thing, Value, Time, and Freedom - A Consideration of Some Key Concepts in Marx's Philosophical SystemMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Marx's Ethics Grounded in Human Self-RealizationDocument28 pagesMarx's Ethics Grounded in Human Self-RealizationMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Zhang 2006 - The Concept of Nature and Historicism in MarxDocument14 pagesZhang 2006 - The Concept of Nature and Historicism in MarxMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Yussoff 2009 Excess, Catastrophe, and Climate ChangeDocument21 pagesYussoff 2009 Excess, Catastrophe, and Climate ChangeMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- 041528919X Routledge Roman Berytus Beirut in Late Antiquity Apr 2004Document22 pages041528919X Routledge Roman Berytus Beirut in Late Antiquity Apr 2004Miguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Yusoff-Biopolitical Economies and The Political Aesthetics of Climate Change - Theory Culture Society-2010!73!99Document28 pagesYusoff-Biopolitical Economies and The Political Aesthetics of Climate Change - Theory Culture Society-2010!73!99Miguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument33 pagesThe University of Chicago PressMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Discourse, Power, and SubjectivationDocument28 pagesDiscourse, Power, and SubjectivationMarj VbDonkerNo ratings yet

- Anderson 1993 - On Hegel and The Rise of Social Theory - A Critical Appreciation of Herbert Marcuse's Reason and Revolution, FiftyDocument26 pagesAnderson 1993 - On Hegel and The Rise of Social Theory - A Critical Appreciation of Herbert Marcuse's Reason and Revolution, FiftyJohn CicchinoNo ratings yet

- Zimmermann 1977 - Sade Et Lautréamont (Sans Blanchot) - Starting Points For Surrealist Practice and Praxis in The Dialectics of Cruelty and Humour NoirDocument23 pagesZimmermann 1977 - Sade Et Lautréamont (Sans Blanchot) - Starting Points For Surrealist Practice and Praxis in The Dialectics of Cruelty and Humour NoirMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Allison 1981 Neitzsche Knows No NoumenonDocument17 pagesAllison 1981 Neitzsche Knows No NoumenonMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Anderson & Fetscher - On Marx, Hegel, and Critical Theory in Postwar Germany - A Conversation With Iring FetscherDocument19 pagesAnderson & Fetscher - On Marx, Hegel, and Critical Theory in Postwar Germany - A Conversation With Iring FetscherMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Andrew 1970 - Work and Freedom in Marcuse and MarxDocument17 pagesAndrew 1970 - Work and Freedom in Marcuse and MarxMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Andersen - Nietzsche's Will To Power As A Doctrine of The Unity of Science 727299819Document18 pagesAndersen - Nietzsche's Will To Power As A Doctrine of The Unity of Science 727299819Miguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Akkerman - Urban Void and The Deconstruction of Neo-Platonic City-FormDocument15 pagesAkkerman - Urban Void and The Deconstruction of Neo-Platonic City-FormMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Cox (1997) The - Subject - of Nietzsche's PerspectivismDocument24 pagesCox (1997) The - Subject - of Nietzsche's PerspectivismMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Alford, F. (1990) Reason and Reparation - A Kleinian Account of The Critique of Instrumental ReasonDocument26 pagesAlford, F. (1990) Reason and Reparation - A Kleinian Account of The Critique of Instrumental ReasonMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Adorno and Horkheimers Idea of EnlightenmentDocument25 pagesAdorno and Horkheimers Idea of EnlightenmentMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Alford 1987 - Eros and Civilization - After Thirty Years - A Reconsideration in Light of Recent Theories of NarcissismDocument23 pagesAlford 1987 - Eros and Civilization - After Thirty Years - A Reconsideration in Light of Recent Theories of NarcissismMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Alcala - Masochism & Representation in Modern Horror - Alien 3Document12 pagesAlcala - Masochism & Representation in Modern Horror - Alien 3Miguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- 38 Basic Joseki... Russian Book For Learning Some Good JosekiesDocument181 pages38 Basic Joseki... Russian Book For Learning Some Good JosekiesMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Adams (1997) Things in ThemselvesDocument26 pagesAdams (1997) Things in ThemselvesMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Albrechtslund 2008 Surveillance and Ethics in Film - Rear Window and The ConversationDocument16 pagesAlbrechtslund 2008 Surveillance and Ethics in Film - Rear Window and The ConversationMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Afshar 2007 Bhor PDFDocument6 pagesAfshar 2007 Bhor PDFMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Aesthetics and Utopian Possibility - Herbert Marcuse and The ArtsDocument4 pagesAesthetics and Utopian Possibility - Herbert Marcuse and The ArtsMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Adorno Husserl Critical TheoryDocument19 pagesAdorno Husserl Critical TheoryMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Vital Points of Go - Shukaku TakagawaDocument256 pagesVital Points of Go - Shukaku Takagawarodriguez.alcalde65No ratings yet

- 123 Food Combining Recipes - Winter PDFDocument147 pages123 Food Combining Recipes - Winter PDFMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Beyond Critical Legal Studies The Reconstructive Theology of DR Martin Luther King, JR., Anthony E. CookDocument44 pagesBeyond Critical Legal Studies The Reconstructive Theology of DR Martin Luther King, JR., Anthony E. CookHJayBee30No ratings yet

- Mloyi SimisosenkosiDocument109 pagesMloyi SimisosenkosiUnçľë SämNo ratings yet

- Neo LiberalismDocument2 pagesNeo LiberalismArtika AshdhirNo ratings yet

- Settling the Accounts of Revolutionary Democracy in EthiopiaDocument31 pagesSettling the Accounts of Revolutionary Democracy in EthiopiaKaleb Berhanu100% (1)

- Sexual Ethics: Christian TeachingsDocument6 pagesSexual Ethics: Christian TeachingsRiaNo ratings yet

- FIRST Semester, AY 2020-2021 I. Course Code/Title:: Vision MissionDocument9 pagesFIRST Semester, AY 2020-2021 I. Course Code/Title:: Vision MissionMonina AmanoNo ratings yet

- Leo Strauss - Liberalism Ancient and ModernDocument285 pagesLeo Strauss - Liberalism Ancient and ModernGiordano Bruno100% (2)

- The Institution of Marriage and The Virtuous Society - Institute For Family StudiesDocument5 pagesThe Institution of Marriage and The Virtuous Society - Institute For Family StudiesSubhay kumarNo ratings yet

- Western and Indian Political Thought, A ComparisonDocument39 pagesWestern and Indian Political Thought, A ComparisonPrakhar Deep57% (21)

- Political Thinkers of EnglandDocument75 pagesPolitical Thinkers of EnglandMitu BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Psci4354.001.10s Taught by Brian Bearry (bxb022100)Document3 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Psci4354.001.10s Taught by Brian Bearry (bxb022100)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- Test Series 1 Optional PsirDocument36 pagesTest Series 1 Optional PsirBalaji ChNo ratings yet

- Chanakaya National Law University, Patna: Roject ORKDocument24 pagesChanakaya National Law University, Patna: Roject ORKPrasenjit TripathiNo ratings yet

- DISS - Mod8 - Dominant Approaches and Ideas of Social Sciences - Insitutionalism and Feminist TheoryDocument37 pagesDISS - Mod8 - Dominant Approaches and Ideas of Social Sciences - Insitutionalism and Feminist TheoryJohnny Jr Abalos100% (1)

- Social Sciences, Norms, and TemporalityDocument19 pagesSocial Sciences, Norms, and TemporalityJosé Manuel SalasNo ratings yet

- Philippine Politics: Activity Sheets Grade 12Document15 pagesPhilippine Politics: Activity Sheets Grade 12Annalie Delera CeladiñaNo ratings yet

- PP DBQ FDRDocument18 pagesPP DBQ FDRcarlirarochaNo ratings yet

- Political Science Honours Cbcs Draft SyllabusDocument65 pagesPolitical Science Honours Cbcs Draft SyllabusBimal HalderNo ratings yet

- Cauton vs COMELEC, April 27, 1967: Tampered election returns justify opening ballot boxesDocument14 pagesCauton vs COMELEC, April 27, 1967: Tampered election returns justify opening ballot boxeslawboyNo ratings yet

- AP European History: Essential Questions & Enduring UnderstandingsDocument10 pagesAP European History: Essential Questions & Enduring Understandingscannon butlerNo ratings yet

- Final Foreign Policy ConclusionDocument24 pagesFinal Foreign Policy ConclusionLawrence Wesley Mwagwabi100% (1)

- "To What Extent Was Liberal Italy A Stable Nation Prior To WWI - " To A Moderately Low Extent Was Liberal Italy A Stable Nation Prior To WWIDocument1 page"To What Extent Was Liberal Italy A Stable Nation Prior To WWI - " To A Moderately Low Extent Was Liberal Italy A Stable Nation Prior To WWITawseef RahmanNo ratings yet

- Heller y Markus - Dictatorship Over Needs - 1983Document336 pagesHeller y Markus - Dictatorship Over Needs - 1983Jorge Iván Vergara del SolarNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 2 Discourses of Nation / NationalismDocument54 pagesChapter - 2 Discourses of Nation / NationalismShruti RaiNo ratings yet

- The Platypus Review, 11 - March 2009 (Reformatted For Reading Not For Printing)Document5 pagesThe Platypus Review, 11 - March 2009 (Reformatted For Reading Not For Printing)Ross WolfeNo ratings yet

- A Case Study of Feminism in IndiaDocument4 pagesA Case Study of Feminism in IndiaSNEHILNo ratings yet

- Combat Liberalism in the Communist PartyDocument3 pagesCombat Liberalism in the Communist PartyAndrés Torres100% (1)

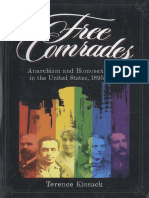

- Kissack - Free Comrades - Anarchism and Homosexuality in The United States, 1895-1917Document247 pagesKissack - Free Comrades - Anarchism and Homosexuality in The United States, 1895-1917Yesenia BonitaNo ratings yet

- Romanticism and The Religious Revival in EnglandDocument10 pagesRomanticism and The Religious Revival in Englandnicolae_dragusinNo ratings yet

- Parliamentary Democracy and Election ProcessDocument3 pagesParliamentary Democracy and Election Processxst819No ratings yet