Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The First Edition of Lucian of Samosata PDF

Uploaded by

Milos HajdukovicOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The First Edition of Lucian of Samosata PDF

Uploaded by

Milos HajdukovicCopyright:

Available Formats

The First Edition of Lucian of Samosata

Author(s): E. P. Goldschmidt

Source: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 14, No. 1/2 (1951), pp. 7-20

Published by: The Warburg Institute

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/750349 .

Accessed: 09/05/2014 17:20

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Warburg Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the

Warburg and Courtauld Institutes.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE FIRST EDITION OF LUCIAN OF SAMOSATA

By E. P. Goldschmidt

of

first edition the original Greek text of

Lucian's Dialogues came out

Theat Florence in 1496. But long before then the amusing and irreverent

compositions of the second-century Syrian author were known to a wide circle

of scholars and littirateursand had produced their effect on various writers.

Such names as Leon Battista Alberti, Jo. Pontanus, Matteo Maria Boiardo

stand out among a multitude of lesser authors whose works betray an admiring

acquaintance with the "scoffer at the gods" (subsannator deorum). Some of

them may have read their Lucian in Greek manuscripts, but many more knew

him only in Latin translations. A number of early Latin versions of single

dialogues existed and exists in manuscripts, and several had appeared in print

before the Greek original became widely accessible, proving that there was a

current demand for such light literature in the second half of the fifteenth

century. There are, as far as I could ascertain, twenty-one distinct editions

of thirteen different dialogues in Latin before the year 1500. The origin of

these translations, the identity of their authors, the tradition of these Latin

texts, offer problems that have not so far been satisfactorilyinvestigated. I will

leave aside all antecedent and subsequent complications that present them-

selves, and I will concentrate on describing the nature, the contents and the

probable origin of one such edition only, the earliest of all, which was printed

at Rome in 1470 and contains six (or rather five) Lucianic Dialogues in Latin.

I will only remarkthat, far from "throwing light" on anything whatsoever, such

research as I have indulged in greatly adds to the complexity of the situation

and, as is so often the case, seems to create more problems than it solves.

The art of printing reached Italy within a dozen years from its invention,

and the two German practitioners who had acquired their skill at Mayence

itself, Conrad Sweynheym and Arnold Pannartz, were brought to Rome by

1467, after they had produced the first examples of their craft in the Benedic-

tine monastery of Subiaco. The perfervid humanist popes, Nicholas V and

Pius II, were by then no longer alive, and their successor on St. Peter's throne,

Paul II Barbo, was personally less eagerly in favour, perhaps even a little

suspicious, of such studies. Still, the atmosphere of Rome in these years

remained imbued with their enthusiasm for classical learning; the college of

Cardinals was in its majority created by the Piccolomini pope and, more

important still, the huge body of officials of the Curia, comprising such men

as Hermolaus Barbarus, Domitius Calderinus, Leonardo Dati, and Gasparo

da Verona could fairly be described as a professional corporation of Latin

stylists. These scribes of the Papal Chancery, the bureaucracy of the world

government of the Roman church, formed the dominant social background

of the city from which prelates were chosen and cardinals emerged. Their

gossip made reputations and ruined careers, and their tastes determined the

fashionable lines of interest among the higher clergy, both resident and visiting

from abroad. In a society so strangely constituted, the commission of a blatant

error of syntax in a letter could make a man ridiculous for the rest of his life,

and the acquaintance with a rare or unknown classical text would confer an

aura of distinction on its possessor.

7

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8 E. P. GOLDSCHMIDT

It is sometimes stated that in the period of the early Renaissance "the

prelates of the Church took up humanist studies with zest" or words to that

effect; it would be more correct to say that in the fifteenth century the com-

position of a work on the finer points of Latin style, the editing, or even the

owning of a rare classical text, proved a most efficacious step towards a

bishopric or some other conspicuous preferment. The humanist officials of

the Curia also revived, for their own benefit and amusement, the semblance

of a university, the "Studium Urbis," where scholarslike L. Valla, Jo. Aurispa,

Pomponius Laetus, lectured on Latin and Greek authors, and which seems to

have functioned more like an academy than a teaching institution.1

When the first Roman printing presses started to operate, their products

show the urgent demand for classical texts which, it would seem, the calli-

graphers had hardly been able to satisfy. They also show by their prefaces

and dedications, that the publication of such texts was considered a means

for attracting patronage from the highest authorities in the Church. Sweyn-

heym and Pannartz were set to work in the palace of a Roman patrician

family and, beginning with a Cicero: Epistolaead Familiares,in 1467, they

poured out a succession of classical authors: Aulus Gellius, Julius Caesar,

Apuleius, Livy, Lucan, Pliny, Vergil, Quintilian, Suetonius, Silius Italicus,

Ovid, and several Ciceros, all before midsummer 1471. They also printed the

first Greek author to come out in a Latin translation who, strangely enough,

is the geographer Strabo (1469). All these volumes are dedicated to Pope

Paul II himself by the editor Giovan Andrea dei Bussi, who seems to have

been the literary manager of the enterprise and who was promptly rewarded

with a little bishopric, Aleria in Corsica. The printer Sweynheym was

eventually presented with a canonry at St. Victor's in Mayence in 1474. It is

clear that this first Roman press was an officially sponsored undertaking,

enjoying a Papal subvention, and that its productions were accepted as con-

tributing to the glory of the reigning Pope.

There were soon other printers in the field, mostly Germans, and other

editors of classical texts, rivalling the industrious bishop of Aleria. The

foremost among them was J. A. Campanus, since 1463 bishop of Teramo

(episcopusAprutinus). He brought out a Quintilian and a Suetonius in 1470

and the first edition of Plutarch's Lives,2translated by various scholars. All

these editions by Campanus are dedicated by him to Cardinal Francesco

Piccolomini, nephew of Pius II,. and later himself for a short time Pope

Pius III. To the same Cardinal he addresseshis printed edition of the Letters

of Phalaris, which the translator, Francesco Griffolini, had dedicated to

Malatesta Novello. The Bologna Ovid of 1471 is dedicated by Franciscus

Puteolanus to Francesco Gonzaga, Cardinal of Mantua. Georgius Merula

dedicated his Plautus in 1472 to Giacomo Zeno, bishop of Padua, Ang. Sabinus

his edition of Ammianus Marcellinus to the bishop of Bergamo.3

1 Leo X

in 1513 stated about this Studium: this Plutarch contains a Life of Charlemagne

adeo scolarium copia defecit, ut quandoque "e graeco sermone in latinum translata,"

plures sint qui legant quam qui audiant. See which is in fact by Donato Acciaiuoli.

Denifle: Univ. d.M.A. I, p. 315. 3 On such dedications the earlier biblio-

2 In view of what we are

presently coming graphers are more informative than the

to it may not be inapposite to mention that modern ones. See: A. M. Quirini, De opti-

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE FIRST EDITION OF LUCIAN OF SAMOSATA 9

Enough examples to show that the appearance of a new classical text under

the patronage of some powerful prince of Church or State was the normal

rule, the dedication of a new edition or translation to a great personage one

of the recognized methods of currying favour and support. Let this be granted

and the fact that the first Lucian came out without any such preliminary

letter or covering flag be taken as a very exceptional feature in a book of this

class. We will try to suggest a reason for this singular omission further on,

but now, having first underlined what the Roman Lucian of 147o does not

contain, we must at last come to a description of the book itself.

It is a rare book; only five copies of it are known to exist: Manchester,

John Rylands Library (Lord Spencer's copy); Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale;.

Modena, Biblioteca Estense; Rome, Biblioteca Corsiniana; Florence, Biblio-

teca Nazionale Centrale.

The small quarto volume contains eighty leaves printed in a rather

clumsily cut Roman type, twenty-four lines to the page. The presswork is

somewhat rough, the line ends uneven; the printer's craftsmanship remains

well below the very excellent standard set by Sweynheym and Pannartz. The

type is that known to students of early printing as the first type of Georg Lauer,

a native of Wuirzburg,who was the fourth or fifth in sequence among the

printers to set up a press at Rome. The book has no title, no subscription and

no date. Nevertheless we incunabulists can positively assert the identity of

the printer and, from the state of the type, the date 1470 as the year of

printing.

How this can be proved would need an explanation in a technical jargon

as illuminating as that of a philatelist discoursing on indentations and wire-

marks, and we had better leave it at that. Lauer's press is neither a distin-

guished one nor a long-lived one; the Lucian is among its earliest products,

by May 1471 this particular type is discarded, by 1481 the activity of the

press comes to an end. In these few years we know of four EditionesPrincipes

of minor classical authors published by Lauer: Quintus Curtius, Pompeius

Festus, Terentius Varro and Nonius Marcellus, all four edited by Pomponius

Laetus.

Lauer's Lucian contains six dialogues: Charon, Timon, Palinurus,

Alexander, Hannibal and Scipio, Tyrannus, Vitarum Auctio,' following in

this order. Each dialogue begins abruptly with the first sentence spoken,

without any heading, but with a space of several inches left blank, not only

to mark the break with the preceding piece, but also to allow for the title

and the names of the interlocutors to be inserted by hand. This is by no means

morumscriptorumeditionibus quae Romae primum Middle Ages, Philadelphia, 1923. But owing

prodierunt, Lindau, I761.--J. B. Audiffredi, to the departmentalized condition of our

Catalogus historico-criticusRomanarum editionum academic studies, this very useful collection

saeculi XV, Rome, I783.--Most valuable: B. of examples is preponderantly devoted to

Botfield, Praefationes et Epistolae Editionibus English and "Romance Philology" texts and,

Principibus auctorum veterumpraepositae, Cam- though it cites a few Latin mediaeval books,

bridge, I86I, who gives the full text of these it practically ignores the humanists.

dedicatory letters. 1 These are Numbers XII, V (-), X, 12,

On the general problem of the function of XVI, XIV of Dindorf's edition, Paris Didot,

patronage the only book known to me is: 1867.

K. J. Holzknecht, Literary Patronage in the

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

0o E. P. GOLDSCHMIDT

an unusual feature in books of this early period which in this respect were

following the example set by the writers of manuscripts. The headings were

left out by the scribe to be supplied last of all by a calligrapher who would

carefully add them in special script and usually in red ink; hence his job was

called that of the "rubricator," and the term "rubric" still remains current

as a synonym for a heading. Both in old manuscripts and in early printed

books this finishing touch of adding the headings in red was often left undone.

They had to be copied in from some model, some exemplar, which frequently

seems to have been no longer to hand when the owner might have liked to

complete his book; or else, failing to employ a competent calligrapher, many

owners preferred to leave the spaces empty rather than spoil the page by

clumsily written headings, inserted by themselves.

We have here five dialogues out of the 166 which have come down to us

as Lucian's work and which, as we know from the first Greek edition and

from the extant Greek manuscripts, were all transmitted together in one

volume from the Byzantine East to the Italian West. Nothing has been added

to the corpus of Lucianic writings in the course of time, though much has

been disputed as spurious by later critics. These few dialogues then just

happened to be available to the editor or the printer in Latin versions. As

we know from manuscripts, a good many more had been turned into Latin

by 1470 and no special significance attaches to the priority of publication of

this selection.

But where, when and by whom were these particular dialogues translated?

The title headings might have told us if they had been printed together with

the text or had been filled in by the rubricator. The Spencer copy at Man-

chester and the one at Modena are no help to us at all; they are in their

virginal state, with the spaces blank as they left the press. When I saw the

Paris copy I was delighted to find all the headings carefully filled in by hand

in red ink and I noted them down. But when I came to inspect the Lucian of

the Corsiniana I found something still more interesting: the source from which

the Paris rubricator obtained his headings. For the copy in Rome contains

not eighty leaves but eighty-one, and the extra, isolated leaf bound first in

the volume is precisely the sheet of "rubrics" or chapter-headings which the

printer supplied with each copy to the purchaser, who could then write them

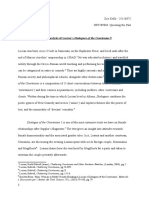

in in their proper places as indicated. (See P1. 4.)1

Such rubricator sheets were, it would seem, quite often supplied by the

early printers-and indeed they were essential to the proper completion of

such a book-but they are not often preserved. For they formed no integral

part of the volume, being loose single leaves, and they were intended to be

thrown away when they had served their purpose. However, sufficient

examples have survived to make us recognize them when they occur, such as

the sheets of chapter headings for the 36-line Bible (about 1460) preserved in

the Paris Bibliotheque Nationale; another example of them is reproduced in

the Catalogueof Early GermanBooks in the Collectionof Charles Fairfax Murray,

London, '913, No. 460, and is now in the Cambridge University Library.

Now that I had the original title-headings, the authentic information sup-

1

The copy at Florence also contains this identified in 1950. (Pressmark L.5.I7.)

leaf. It has only come to light and been

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Luctantdialogus 9 infmrbit

Char5 latinus p Ri-

ideuo f

sad reueriddfftmu

cardinaI patredominum

orinenifm.Seraphius,

ntu.

Dtalogargume Demontile.

Incptt d4talgus cuiusiterlocutores

pmilit .Mer-

urius Caron. Quidturides charon.

hoc Luctaniopusp meBeroldu grecotra uti

tib de mitto nex

OCzbecca•is incltte peregrie.

ut ex tua

corre&5e laboremeo.atiqeteritaseorv-

orato1

at Juptter

amabilths. EptRola

quepofita

retro poRtractadtde p debetfignai pfi

iPattoquedi aii ratr utantta

.t-

Obfecro. tfcdfetcet.

Lucati dtalogus denuo

pRinutz fqutr tra1atus

cuius

interlocutores nt Charon Palinus. Obcro.

de

parefhrntt. :,

fun :

Cha -:oth ::uler--

cultustel1octores

Luctaniurib AMexa:.derde uniattoneu

clariffi8iFabula lt .

curiusRadanbatusMegapites Cinifeus& Mtiuf

oriftaea

lucerna

rnrortuus a leautsdernuotrI`&atap uenera-

ueneirao

ea Luct

Eiudpatr

bd Criofto a tranflatustraatuflus

ani pereundla

pfon2.Ro.por de

in.S.Balbina.

itap,.culus u untVitor

intertocutores

uendtttolne

MercuriusLtrptor Philofopbus.

Sheet of Rubrics supplied with Lauer's Lucian, Rome, 1470 (p. 10)

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE FIRST EDITION OF LUCIAN OF SAMOSATA 11

plied by the editor himself on the authors of these versions, everything should

have been plain sailing. Alas, the more I examined this promising page, the

more I was puzzled. There was not much I knew about the early translators

of Lucian before I met with this sheet; but that little was sufficient to show

that the man responsible for these "model" title-headings had some surprising

things to tell us. On some of the most familiar of these dialogues liis informa-

tion is quite plainly, even fantastically, wrong. On others it seems to be not

only new, but of great weight and importance. However, an editor who can

put down the Palinurus,which is not by Lucian at all, which is not even

Greek at all, but a fifteenth-century Latin composition by Maffeo Vegio, as

"per Rinuccium denuo translatus," forfeits all claims to credence, and his

testimony must be scrutinized item by item with the utmost scepticism.

Lauer's Lucian begins on its first page with a resume of the salient points

of the Charon,the first of the following dialogues. It begins:

Bona fabula hec que loquitur nobis tot utilia. Aurum quid sit et quam

stulte tanti reputatur, etc.

This Prologue continues in similar strain for twenty-two lines altogether. It is

not easy to decide whether this piece is intended as prose or as some kind of

accentuated free verse, something like the ancient Roman Saturnians.

On the next leaf there follows:

I. Charon.

Above the first of the dialogues in the Rome quarto the rubricator is told

to write:

Luciani dialogus qui inscribitur Charon, latinus per Rinutium denuo

factus, ad reverendissimum patrem dominum Johannem cardinalem

Morinensem.

This is the Charonsive Contemplantes(Dindorf XII) translated'into Latin

by Rinuccio of Arezzo (or of Castiglion-fiorentino), on whom see D. P.

Lockwood: "De Rinucio Aretino Graecarum literarum interprete," in Harvard

Studies in Classical Philology, 1913, XXIV, pp. 5I-Iog9. Rinuccio (best known

perhaps as the translator of the frequently printed Latin version of Aesop's

Fables) had been to Constantinople himself (1421-23) and brought back,

among other codices, a MS. of Lucian from which he translated the Charon

and the VitarumAuctio (see below) in the summer of 1441 or 1442. At that

time he was employed in the Roman chancellery and also held a chair of

Rhetoric in the "Studium Urbis" until his death in 1456 or 1457. He dedicates

his version to Jean Le Jeune, Cardinal Bishop of Th6rouanne (Cardinalis

Morinensis) 14I I-51, elevated to the purple in 1439 by Eugene IV, a great

book-collector and hunter of manuscripts, on whom see Sabbadini, Scoperte,

I, p. 194.

The words "latinus denuo factus" are correct; there exists an earlier trans-

lation, never printed, of which we will have to say something below under

Timon. The dedicatory letter to Card. Le Jeune begins with "Seraphius

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

12 E. P. GOLDSCHMIDT

Urbinas, vir utriusque juris . . ." and is here printed in its proper place.

Another dedication to Lorenzo Colonna, belonging to the same dialogue, is

found in this edition also, but misplaced on Fol. 56b in front of the Tirannus.

On these two dedicatory letters see Lockwood, loc. cit., p. 53 and p. 96.1

II. Timon.

Lucian's dialogue on the Misanthrope (Dindorf V) which perhaps had

as momentous an influence on European literature as any of his writings;

M. M. Boiardo's Timone,Shakespeare's Timonof Athens,Moliere's Misanthrope

derive from it.

The sheet of rubrics gives the heading:

Hoc Luciani opus per me Bertoldum ex greco translatum tibi de Czambec-

cariis mitto, oratorum inclite Peregrine, ut ex correctione tua et labore

meo aliqua eternitas oriatur.

The information contained in this rubric is new and important. Of the

translator Bertoldus nothing at all is known so far, but the patron to whom

he addresseshis version, Peregrino de' Zambeccari, was chancellor of Bologna

and died soon after 14oo. The dedication therefore demands a remarkably

early date for this translation, a period much earlier than that in which Greek

manuscripts become ordinarily current in Italy, a date anterior by a quarter

of a century to the return of Aurispa and Rinuccio from Constantinople

(1423) with their codex of Lucian's dialogues.

It is, fortunately, possible to confirm this early date from two independent

sources and so to establish the authenticity of the rubric.

The same version of the Timon,together with a Latin translation of the

Charon(to which I have referredabove) is found in a MS. in the Laurenziana

at Florence, Plu. XXV sin. 9. There it has no heading or dedication, nor

does it give the translator's name. The Codex comes from Santa Croce and

has the full subscription:

1403. 26 mai. scripta sunt haec Florentiae Frater Thedaldus tunc vacans.

On Thedaldo della Casa and his gift of books to Santa Croce in 1406 see

R. Sabbadini: Scoperte. Nuove Ricerche,p. 175.2

Reliable confirmation that a translation, and presumably this translation,

of the Timonwas in existence in 1403 comes from another source. Remigio

Sabbadini in NuovoArchivioVeneto,1915, N.S. XXX, pp. 219 ff., published a

letter from Antonio di Romagno, dated January 16, 1403, addressed to Pietro

Marcello, Bishop of Ceneda (1399-1409, died 1429). In this letter Antonio

gratefully acknowledges the loan of a book to which he refers as "tuum

Timonem." Without disrespect for the great authority of Sabbadini we must

1

See also the rubricator-sheet, lines io- 2, 2The only other MS. known to me con-

where the editor notices that the letter to taining these two early translations of the

Colonna is wrongly placed, but creates fresh Charon and the Timon is Vat. lat. 989, fols.

confusion by suggesting it belongs in front of 81-96, but it neither gives a translator's name

the Palinurus. nor can it be dated.

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE FIRST EDITION OF LUCIAN OF SAMOSATA 13

be allowed to disagree if, from the mere occurrence of the pronoun "tuum,"

he jumps to the conclusion that Pietro Marcello must have been not only the

owner of the book but the translator of Lucian's Timonfrom the Greek.

Equally unconvincing is Sabbadini's suggestion made in the same paper

that the translation of the Charonin the above-mentioned MSS. is the work

of Peregrino de' Zambeccari himself. This proposal is advanced solely "merce

una stampa dell'ultimo Quattrocento che assegna la traduzione di questo

dialogo a Peregrino de' Zambeccari."

This is an odd way of citing an authority and it seems clear that, for once,

Sabbadini must have been careless in making or preserving his notes. It

would be impossible to verify his assertion (for it is certain that no printed

edition contains in its text such an ascription of the Latin Timon),if it were

not that L. Frati in editing the Epistolarioof Peregrino de' Zambeccari in the

Fontiper la Storiad'Italia, 1929, had given us a little more information on the

source of Sabbadini's statement. On page xxii of his introduction Frati cites

from a copy of Lucian's Opuscula plurima,Venice, S. Bevilaqua, 1494, preserved

in the Bibl. Nazionale Centrale at Florence (pressmark L.5-I7) the hand-

written heading over the Charon: "Hoc Luciani opus . . . aliqua eternitas

oriatur" in its entirety, which we now know to derive from Lauer's sheet of

rubrics. Frati has nothing to say on the translator's name Bertoldus and for

us, who know its origin, this written copy of 1494 has lost all evidential value;

moreover it is found scribbled out of its proper place, for it is not over the

Timonbut over the Charon,which in that edition is given in Rinuccio's trans-

lation as cited above.'

The only little piece of corroborative evidence which I have found so far,

that translations of Lucian by a man named Bertoldus were in existence, is the

entry in the inventory of the library of Duke Borso d'Este made in 1467:

Lucianus ex graeco translatus per Bertholdum in membranis in forma

mediocri Littera moderna

as given by G. Bertoni: La Biblioteca Estense e la Coltura Ferrarese, 1471-1505,

Turin, 1903, p. 216.

That, I am afraid, is all I have been able to discover about this shadowy

Bertoldus, who, whoever he was and wherever he worked, must be counted

among the earliest of the Renaissance translators from the Greek.

III. Palinurus.

After the Charonand the Timonthere follows in the first Roman edition

1 The recent

rediscovery of the Florence we reproduce. I cannot help adding that

Lucian (see p. Io, n. I) has rendered the above- since 1947 I have gone four times to the Bibl.

described confusion even more involved. Naz. in quest of this Lucian. It remained

Both Frati and Sabbadini must have been "irreperibile" and I have not seen it yet. But

extraordinarily slipshod. There is no 1494 I owe reliable information on its existence and

Lucian with MS. headings in the Biblioteca its contents to my friend Comm. T. de

Nazionale Centrale. The pressmark Frati Marinis, who has succeeded in examining it

cites is that of the 1470 Lucian which has no for me.

notes, but does contain the rubricator-sheet

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

14 E. P. GOLDSCHMIDT

the dialogue Palinurus,and Lauer's editor instructs the rubricator that he

should entitle it:

Luciani dialogus per Rinutium denuo translatus cuius interlocutores sunt

Charon et Palinurus. Obsecro ...

We may well wonder how at the time ard place when this was printed,

Rome I470, such a grossly false assertioncould be published. For the Palinurus,

a rather flat-footed discussion between Aeneas' unfortunate helmsman and

Charon, the ferryman, on the miseries of all estates on earth, is not by Lucian

at all. No Greek original of it exists, so that it could not be "translated"

either by Rinuccio or by anyone else. The Palinurusis a composition by Maffeo

Vegio of Lodi (I406-58), who from 1433 onwards was one of the more im-

portant officials of the Roman Curia. He was an industrious and prolific

writer, both in prose and in verse, and he liked to exercise his talent for

imitative composition by producing work which was taken to be a deceptive

"pastiche" of some ancient author. He was bold enough to write a thirteenth,

concluding canto for Virgil's Aeneid,which has found its way with, or even

without, his name into several of the early editions.

Lucian seems to have been one of Vegius' favourite authors. The Palinurus

is quite closely modelled on Lucian's writings, and not only the names of the

interlocutors, but the technique of composition prove his familiarity with the

Greek satirist, though we cannot be certain that he read him in Greek. Beside

the PalinurusVegius wrote at least two other "Lucianic" dialogues, a Disputatio

interSolem, Terramet Aurum,and the Philalethes,sive veritasinvisa. This seems

to have been a very popular piece with the fifteenth-century public and there

are a number of printed editions of it from 1473 onwards, generally with the

true author's name. But I have found at least one Philalethes,printed at

Cracow, by Florian Ungler in 1512, in which the author is given as Lucian

of Samosata.1

The bibliographical history of the Palinurusis amusing and peculiar. Its

occurrence in the Roman Lucian is no doubt its first appearance. But not

long after, in 1473, it is printed again at Cologne from William Caxton's

anonymous press in a volume of Ten Dialogues(Hain 6107). Here it is seen

together with the Philalethes,both of them with Maphaeus Vegius' name as

the author, and it is entitled Dialogus defoelicitate et miseria. On May 13, 1497,

Guillaume Le Signerre at Milan brings out a collection of Maphaeus Vegius'

writings in which he includes the Dialogus de Foelicitateet Miseria (Hain

15933). But in March 1497 another Milan printer, Ulrich Scinzenzeler, had

published a collection of Lucian's works in which the same piece is contained

as Lucian's Palinurus(Hain 10262). All this goes to show that the fifteenth

century was not keenly interested in questions of authorship. But still we

cannot help wondering how a Roman editor could in 1470 attribute the

Palinurusto Lucian, when its author Vegius had died in Rome as recently as

1458, and how he could give Rinuccio as its translator, who was certainly

still alive in I456. To my mind this blunder confirms the impression that

Lauer's Lucian is a surreptitious and almost clandestine publication.

1 See K.

Piekarski, Pierzwa Drukarnia Fl. Unglera, 1926, No. 12.

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE FIRST EDITION OF LUCIAN-OF SAMOSATA 15

IV. Scipio.

The twelfth of Lucian's Dialogues of the Dead, the Dispute between

Alexander, Hannibal and Scipio, who in the underworld appeal to the judge

Minos to decide who was the greatest general of the three.

For this piece the sheet of directions for the rubricator prescribes:

Prohemium libelli de prestantia trium principum, videlicet Alexandri,

Annibalis et Scipionis, translati per clarissimum virum Leonardum

Aretinum.-Cum in rebus bellicis.

The attribution of the translation to Leonardo Bruni is a surprising and

quite unwarranted slip on the part of the anonymous editor. There are few

of the early Lucian translations about whose origins we are more reliably

informed than on the Scipio. On the other hand we possess exceptionally

thorough-going studies on Bruni's translations, based on the examination of

hundreds of MSS., viz. L. Bertalot, "Ubersetzungen von Leonardus Aretinus"

in Quellen & Forschungenaus italienischenBibliothekenund Archiven,XXVII,

I937; supplementing: H. Baron, Leonardus BruniAretinus. . . mit einerChrono-

logie seiner Werke und Briefe, Leipzig, 1928. Neither of them has any mention

of Lucian whatsoever, from which we may conclude that nowhere have they

met with this false ascription, which seems to be entirely due to the imagina-

tion of Lauer's editor.

In fact the AltercatioAlexandriAnnibaliset Scipionis,as found here or any-

where else in print or in manuscript before I500, is the Latin version by

Giovanni Aurispa. It was Aurispa who, together with Rinuccio, brought the

Greek manuscript from Constantinople in 1423, and it was Aurispa who in

1425 at Bologna made this translation and dedicated it to Battista Capodiferro,

Governor of Bologna. In numerous MSS,1 though strangely enough in none

of the printed editions, this dialogue is preceded by the letter: "Ad Baptistam

caput de ferrum Romanum civem, disciplinae militaris virum et praetorem

Bononiae, Aurispa . . ." The letter itself begins with the words: "Cum in

rebus bellicis . . ." and these are the words before which Lauer's sheet directs

you to place the heading. In fact the printed text of the Roman edition gives

the whole of Aurispa's letter, though without its address, before it gets to:

"Alexander: Me, o Lybice, praeponi decet .. ." the opening words of Lucian's

dialogue. Before this beginning the rubricator is to insert:

Incipit libellus altercationis Alexandri et Annibalis de prestantia.

A curious peculiarity of Aurispa's version seems worth noting, even in this

condensed account. In Lucian's Greek original Scipio only comes in at the

very end with one sentence to protest against Hannibal's claims, and the

judgment of Minos is given: Alexander to be first, Scipio second, then third

perhaps Hannibal, who is not to be despised either.

In the Latin "translation" Scipio by no means confines his claim to a

single sentence, but gives a substantial account of his African victories; he

1 On the

many MSS. and on the curious F6rster, "Zur Schriftstellerei des Libanios,"

deviation from the Greek original, see: R. in Jahrbuchfir Philologie, 1876, pp. 219 if.

2

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

16 E. P. GOLDSCHMIDT

concludes with the statement that, not for insisting on his own personal prefer-

ment, but "pro patria haec dicta sunt." Thereupon Minos gives hisjudgment:

"Per Jovem. o Scipio, et recte et uti Romanum decet locutus es"; you are to

be put first, Alexander to be second, and third, perhaps, Hannibal, for he is

not to be despised either.

Fdrster, loc. cit., is right, no doubt, in seeing in this arbitrary alteration a

compliment to the Roman military Governor to whom Aurispa dedicates his

version. I would add that so high handed a "patriotic" distortion of the text

before the translator appears to me an ominous symptom of the spirit of

nationalism, which the humanists, Petrarch' himself at their head, were to

inject into European literature.

V. Tyrannus,seu Trajectus(graece KccraXou;,Dindorf XVI).

Lucian's Tyrant follows his favourite device of presenting his characters

in the ferry across the Styx on their way to the underworld. The murderous

tyrant arrives, full of conceit and arrogance, and holds up the other passengers

by his blustering demands to be immediately returned to earth. He is dragged

before the judges, convicted by the testimony not only of human witnesses

but also of his bed and of his night lamp, and ultimately condemned never

to drink of Lethe and so never to lose the haunting memory of his crimes.

The heading for this Dialogue reads:

Luciani viri clarissimi fabula de venatione (corrected by hand into:

navigatione) vel tiranno, cuius interlocutores sunt Charon, Clotho,

Mercurius, Radamantus, Megapentes, Ciniscus et Micillus mortuus,

lucerna et lectus; denuo translata per venerabilem patrem Cristoforum

Personam, Romanum, Priorem in S. Balbina.

There is no reason to doubt the truth of this attribution; Christophorus

Persona (1416-86), Prior of the Guilelmite monastery of Santa Balbina at

Rome, was an industrious translator from the Greek who, towards the end of

his life was appointed Prefect of the Vatican Library by Innocent VIII. Two

other of his translations at least appeared in print in his lifetime, one of them,

Twenty-fiveSermonsof St. John Chrysostom (Hain 5039), printed by the same

Georg Lauer in the same type and in the same year as this Lucian. The

other is an Origen Against Celsusprinted also at Rome by Georg Herolt in

1481 (Hain 12078). His translations of the Historiesof the Gothsby Procopius

and by Agathias were published in I506 and in 1516. A notice on him by

Fabricius: Bibliothecamediaeet infimaeLatinitatis,1858, I, pp. 348-9, enumerates

these and a few other works from his pen, but not this Lucianic dialogue.

Note the words "denuo translata" in the rubric, which in the case of the

Charonwe have found to be true. I have found no trace of any such earlier

translation of the Tyrannus,but the possibility of its existence is by no means

to be excluded. However I have no note of any MS. containing the Latin

Tyrannus.

1 Petrarch: see Africa, VIII, lines 42-232, without some trace of pro-Italian fervour and

where Scipio also is awarded first place, not anti-Greek animosity.

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE FIRST EDITION OF LUCIAN OF SAMOSATA 17

VI. VitarumAuctio(Dindorf XIV).

The Auctioning of the Philosophers' Lives must have been a puzzling piece

for a fifteenth-century reader. Without some slight knowledge of the doctrines

of the Pythagoreans, the Cynics, the Epicureans, the Peripatetics, etc.,

Lucian's satirical idea of having them put up for auction one by one and

cross-examined by the intending purchasers, must have been barely intel-

ligible. That this was the case becomes evident when we observe the grotesque

mistakes and mistranslationsin the early printed versions. Whether Rinuccio's

authentic Latin rendering was much better, I for one cannot tell. I have not

examined the MSS., and I would suspect that they might be nearly as un-

faithful to the original text as the printer's productions seem to be. The

choice of this Dialogue for translation suggests the humanists' superior, "high-

brow," attitude which put a blight of sterility on so great a proportion of their

labours. They were so often pretending to understand texts which, quite

plainly for us to judge, remained utterly obscure to them.

The version here printed is that by Rinuccio of Arezzo, on whom see

above under Charon(p. I ), but the printed text retains no trace of the

dedicatory epistle to Seraphius of Urbino, which should precede it. This

translation is found in MSS. generally following that of the Charon(see Lock-

wood, loc. cit.) and this explains how Lauer's editor has come to prescribe the

rubric:

Eiusdem Luciani per eundem translatus tractatulus de Venditione

Vitarum, cuius interlocutores sunt Venditor, Mercurius, Emptor, Philo-

sophus.

Since in Lauer's quarto Rinuccio's VitarumAuctiodoes not follow upon

the Charon,but immediately after Persona's Tyrannus,the words "per eundem

translatus" are utterly misleading. *Butwe have by now ceased to wonder at

the erratic fantasies of Lauer's editor.

All this lengthy analysis of a slender volume of eighty leaves may appear

somewhat involved and complicated, and if the reader should happen to be

a believer in "progress," he may well ask: What does it prove except that the

first edition is a very bad one? Nevertheless I would plead that if we admit-

tedly learn little about Lucian from such research, we are brought to see more

vividly than we may have done, how the "Revival of Learning" worked in

practice. We were led to find out something about the persons of the first

translators from the Greek and about their patrons. We had to recognize

that, contrary to widely current opinion, it was long before the Fall of Con-

stantinople that the Western World became curious about the Greek classics.

We met with a crass example of the indifference to authenticity and to

problems of authorship prevailing among the fifteenth-century scholars, who

would enjoy their Palinuruswhether by Lucian or by Vegio. We have en-

countered an early instance of patriotic falsification of an ancient text in

Aurispa's Scipio. And we have left aside many pertinent reflections on the

subsequent fate and influence of these early translations, a subject which I

hope to pursue more fully in some future publication.

The editor of Lauer's Lucian, the man responsible for the prescribed title-

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

18 E. P. GOLDSCHMIDT

headings and for the muddled displacements in the text, who gave the printer

his script and, presumably, hired or encouraged him to publish it, does not

make himself known. It would not be for fear of pedantic strictures like ours

on the incompetence of his editorship that he hides his identity; he must have

had other reasons. He does not seize the opportunity to offer his production

to some patron of learning and so to win favour and a little reputation, to

"immortalize" his name and that of his protector, as the composers of prefatory

letters were so fond of proclaiming.

It is permissible to make a guess at the motives for such unusual self-

effacement. This Lucian is published in Rome in the year 1470. Very shortly

before that date, in 1468, an event of nearly tragic consequences had caused

some commotion in the literary circles of the city. All the members of

the AcademiaRomanawere arrested on a charge of conspiracy against the

government of Pope Paul II. They were all closely examined under torture

in the Castello Sant' Angelo, soon found to be guiltless of any political machi-

nations, and all of them were released within a year. Jo. Baptista Platina,

the historian of the Popes, was one of the members who suffered this indignity

and he has left us an account of his experience in his, comprehensibly, some-

what spiteful life of Paul II, first published in his Vitae Pontificum,Venice,

1479-

The AcademiaRomanawas a circle of literary and scholarly people, mainly

composed of the pupils and admirers of Pomponius Laetus, who was the

presiding figure of the society; it mostly met in his house on the Quirinal

and hence is sometimes referred to as SodalitasQuirinalisor AcademiaPom-

poniana. From 1465 until his death in I498 Pomponius held a salaried

lecturership in the Roman University, the Studium Urbis, and his courses on

Roman antiquities were assiduously followed by numerous disciples. His

"Academy" included some very serious scholars, like Jo. Baptista Platina and

Marcus Antonius Sabellicus, the historian of Venice. But it also comprised a

crowd of young poets and enthusiasts for the antique. One of the distinctive

features which seems to have originated among them was that all its members

gave themselves classical names, a custom that persisted in learned societies

in and outside Italy for generations. In their trial this discarding of their given

Christian saints' names and their use of pagan names like Pomponius, Calli-

machus or Pantagathus was one of the points given prominence in their

questioning, even by the Pope himself. But their fervour for antiquity did not

stop there; they publicly performed some comedies of Plautus in the Piazza

Navona, they even went so far as to celebrate the ancient festival of the Palilia

on the anniversary of the foundation of Rome. There undeniably was a

tendency to flirt with paganism among the less restrained members of this

Academy, and there was, it would seem, ample ground for the accusation.that

their morals were suspect.

In fact we may well doubt whether the outcome of their trial would have

been as mild as it fortunately proved to be if the interrogators had known of

the astonishing, if rather puerile, inscriptions which Comm. G. B. de Rossi

encountered in the Roman Catacombs in 1852, and which he published in

his RomaSotteraneaCristiana,I864, I, pp. 2-9. It is evident how profoundly

he was shocked and upset by these traces of the Roman Academy as his earliest

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE FIRST EDITION OF LUCIAN OF SAMOSATA 19

predecessors in penetrating into the underground chapels and venerable

sepulchres of the early martyrs, in the Cemetery of Calixtus. On the walls of

these hallowed passages we can see-not scribbled, but traced in lapidary

capitals-the record of the presence of: Pantagathus, Mammeius, Papirius,

Minicinus, Aemilius, Unanimes Perscrutatores Antiquitatis, regnante Pom.

Pont. Max. (signed:) Minutius Rom. Pup. Deliciae. And again: Pomponius

Pont. Max., Pantagathus Sacerdos Achademiae Rom. How far such mural

writings should be taken seriously may be a matter of opinion, but that the

"reigning pontiff" Pomponius and the "Priest of the Roman Academy"

Pantagathus were not regarding themselves as Christians, but, playfully

perhaps, as servants of some pagan cult, can hardly be doubted.'

A society like the Academy of Pomponius, a group of preponderantly

young enthusiasts for pagan antiquity, a kind of advanced, "highbrow" clique

in a Rome mainly dominated by canon lawyers and purposeful careerists,

was a circle in which Lucian's ironical and disrespectful satires would find

their readers and admirers, where every newly translated piece from his pen

would circulate and be enjoyed. It seems to me most likely that the haphazard

bundle of six dialogues came to Lauer's printing office from some up-to-date

young member of Pomponius' classes on Roman Archaology. The happy-go-

lucky attitude of the "editor" towards his duty to provide reliable information

on the authors of his versions stamps his publication almost as an under-

graduate's joke.

The person of the printer, Georg Lauer, affords another clue that points

in the same direction. For among the comparatively few productions of his

press we met with four classics, the Curtius Rufus, the Varro, the Festus and

the Nonius Marcellus edited by Pomponius Laetus in 1471-72.

There must have been personal contact between Lauer and Pomponius as

between printer and proof-reader at the least. Witness also the explicit

reference to Lauer in the preface to the Nonius Marcellus as reprinted by

B. Botfield, loc. cit., p. 138. Not that I would suggest Pomponius himself for

the r6le of the first editor of Lucian; he was too solemn a pedant to care for

such levities and too anti-Greek to exert himself on behalf of an author so

conspicuously lacking in Roman gravity. But the link between the printer

and the Academy through the person of its president is demonstrable.

Granted that some minor member of the AcademiaRomanamay have

conceived the project of publishing some Lucianic dialogues, he would surely

have good reason for keeping his name out of the printed book. It would

barely be twelve months since he had come out of prison, absolved of a silly

charge of conspiracy, but after a most unpleasant examination, in which the

prosecution made ample use of accusations of paganizing impiety, of moral

1 On Pomponius Laetus and his Roman useful footnotes is to be found in G. Zippel's

Academy we find some information in Tira- edition of Mich. Canensius, "De Vita et

boschi, Storia della Letteratura Italiana, .1795, Pontificatu Pauli II," in the Rerum Italicarum

VI, I, pp. 99-104, and L. Pastor, History of Scriptores, 1904, III, pt. 16, pp. 153-6. A

the Popes, 1894, IV, pp. 41-66. Also in J. E. fuller study of Pomp. Laetus and especially

Sandys, History of Classical Scholarship, II, of the trial of the Academicians, based on

pp. 92-3; M. Maylender, Storia delle Accademie manuscript material in the Vatican, is V.

d'Italia, 1929, IV, pp. 320-7. A cluster of Zabughin, Pomponio Leto, I909- I.

I

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

20 E. P. GOLDSCHMIDT

laxity, and of notorious irreverence to authority, implicating the entire

Academy and each one of its members singly. Paul'II was still alive-he died

the next year-and it can hardly have been advisable for a young scholar to

flaunt his admiration for Lucian while his regime lasted.

Nor, under such circumstances, would a dedication of a volume of Lucian

to some influential prelate have been helpful or even acceptable. To the

half-learned and to the severer scholars little would be known about Lucian,

then as now, except that he was a naughty author.

The supposition that the first printed Lucian came to see the light through

some impulse generated in the Roman Academy is admittedly pure guesswork;

but it may appear as plausible to others as it does to me. May I give further

rein to my imagination and record what may well have passed between the

printer and the young scholar who brought the manuscript?

"What about a dedication to some cardinal?" asked Lauer. "Never

mind," replied the editor, "this book will sell itself."

This content downloaded from 147.91.1.45 on Fri, 9 May 2014 17:20:31 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- CreativityDocument1 pageCreativityRosevereNo ratings yet

- Doctors ViewDocument2 pagesDoctors ViewVu Manh CuongNo ratings yet

- Future of EnglishDocument1 pageFuture of EnglishGenie SorianoNo ratings yet

- FootballDocument1 pageFootballabdel2121No ratings yet

- Professionals ConfidenceDocument2 pagesProfessionals ConfidenceSofiaNo ratings yet

- Learnenglish ProfessionalsDocument1 pageLearnenglish ProfessionalsMẫn ĐứcNo ratings yet

- Study DiariesDocument1 pageStudy DiariesNguyễn MinhNo ratings yet

- Writing CVDocument2 pagesWriting CVbongchuyen89No ratings yet

- FairtradeDocument2 pagesFairtradeVu Manh CuongNo ratings yet

- Emotional IntelligenceDocument1 pageEmotional IntelligenceVu Manh CuongNo ratings yet

- Intercultural CompetenceDocument2 pagesIntercultural CompetenceVu Manh CuongNo ratings yet

- Learnenglish Podcasts Professionals Managing Conflict 0Document2 pagesLearnenglish Podcasts Professionals Managing Conflict 0paco1980rabNo ratings yet

- Web TelephonyDocument2 pagesWeb TelephonyNguyễn MinhNo ratings yet

- CinepoliticsDocument1 pageCinepoliticsananthojuNo ratings yet

- Learnenglish Professionals: Listen To A Lecturer Giving Advice On How To Improve Study SkillsDocument1 pageLearnenglish Professionals: Listen To A Lecturer Giving Advice On How To Improve Study SkillsNguyễn MinhNo ratings yet

- Strategic ThinkingDocument1 pageStrategic ThinkingNguyễn MinhNo ratings yet

- Learnenglish Professionals: Presenter: Linda: Thanks. Presenter: Linda: Presenter: LindaDocument1 pageLearnenglish Professionals: Presenter: Linda: Thanks. Presenter: Linda: Presenter: LindaMilos HajdukovicNo ratings yet

- ComplainingDocument2 pagesComplainingVu Manh CuongNo ratings yet

- Currency ExchangeDocument1 pageCurrency ExchangeEmanuela GioNo ratings yet

- Art and BusinessDocument1 pageArt and BusinessMilos HajdukovicNo ratings yet

- CoachingDocument1 pageCoachingVu Manh CuongNo ratings yet

- LebanonDocument1 pageLebanonAlejandro LandinezNo ratings yet

- Web2 0Document2 pagesWeb2 0Nguyễn MinhNo ratings yet

- Engineering Projects PDFDocument2 pagesEngineering Projects PDFhayatiNo ratings yet

- Team WorkingDocument1 pageTeam WorkingNguyễn MinhNo ratings yet

- Cultural HeritageDocument1 pageCultural HeritageVu Manh CuongNo ratings yet

- BagpipesDocument1 pageBagpipesAbhiraj JainNo ratings yet

- 65 PDFDocument2 pages65 PDFCar DriverNo ratings yet

- Pricing Strategies PDFDocument1 pagePricing Strategies PDFankitNo ratings yet

- Learn English ProfessionalsDocument1 pageLearn English Professionalsluu_huong_thao6537No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Mary Beard and John Henderson, With This Body I Thee Worship: Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity'Document24 pagesMary Beard and John Henderson, With This Body I Thee Worship: Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity'JonathanNo ratings yet

- The Letter of Mara Bar Sarapion in ConteDocument264 pagesThe Letter of Mara Bar Sarapion in ConteDarcicley LopesNo ratings yet

- Erasmus and More, A Friendship Revisited, Baker-SmithDocument19 pagesErasmus and More, A Friendship Revisited, Baker-SmithCarlos VNo ratings yet

- Lucian (Loeb Vol. 6)Document524 pagesLucian (Loeb Vol. 6)jcaballeroNo ratings yet

- Works of Lucian of Samosata - Volume 01 by Lucian of Samosata, 120-180Document196 pagesWorks of Lucian of Samosata - Volume 01 by Lucian of Samosata, 120-180Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- Milenkovic DunjaDocument76 pagesMilenkovic DunjaMabrouka Kamel youssefNo ratings yet

- Lucian - No. VII (Loeb Classical Library)Document403 pagesLucian - No. VII (Loeb Classical Library)jcaballero100% (2)

- Lucians Dialogues of The Courtesans - Hayes NimisDocument173 pagesLucians Dialogues of The Courtesans - Hayes NimisFelipeNo ratings yet

- Hunink Apul Flor 2001Document130 pagesHunink Apul Flor 2001josansnchzNo ratings yet

- Angelos Chaniotis-Staging - and - Feeling - The - Presence - of - God PDFDocument18 pagesAngelos Chaniotis-Staging - and - Feeling - The - Presence - of - God PDFMartin AdrianNo ratings yet

- Lucian (Loeb Vol. 2)Document548 pagesLucian (Loeb Vol. 2)jcaballeroNo ratings yet

- Reading FictionDocument320 pagesReading FictionVictoria MartinezNo ratings yet

- Moreana, No.: Utopian Laughter: Lucian and Thomas MoreDocument11 pagesMoreana, No.: Utopian Laughter: Lucian and Thomas MoreMartín GonzálezNo ratings yet

- English Satires by VariousDocument219 pagesEnglish Satires by VariousGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Trips To The Moon by Lucian of Samosata, 120-180Document62 pagesTrips To The Moon by Lucian of Samosata, 120-180Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- Lucian Source Analysis Queer History FinishedDocument3 pagesLucian Source Analysis Queer History FinishedZoe KellyNo ratings yet

- Lucian's Dialogues of The Gods - Hayes and Nimis (March 2015) PDFDocument166 pagesLucian's Dialogues of The Gods - Hayes and Nimis (March 2015) PDFuriz1No ratings yet

- Ulysses in Antwerp: The Lucianic Aethetic of Thomas More's UtopiaDocument151 pagesUlysses in Antwerp: The Lucianic Aethetic of Thomas More's UtopiaEric VerhineNo ratings yet

- Macleod - 1974 - Lucian's Knowledge of TheophrastusDocument2 pagesMacleod - 1974 - Lucian's Knowledge of TheophrastusSIMONE BLAIRNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Books OnlineDocument31 pagesCambridge Books OnlineSarón PadramiNo ratings yet

- PriceDocument152 pagesPriceRaimundo TinoNo ratings yet

- Polyaenus Scriptor MilitarisDocument42 pagesPolyaenus Scriptor MilitarisRadu UrloiuNo ratings yet

- Untangling Blackness in Greek Antiquity - Sarah F. DerbewDocument278 pagesUntangling Blackness in Greek Antiquity - Sarah F. Derbewb2vrngm7rvNo ratings yet

- Eunucos en AntigDocument18 pagesEunucos en AntigMaria Ruiz SánchezNo ratings yet

- Lucian (Loeb Vol. 5)Document564 pagesLucian (Loeb Vol. 5)jcaballero100% (1)

- Shea, Louisa - The Cynic Enlightenment PDFDocument285 pagesShea, Louisa - The Cynic Enlightenment PDFd-fbuser-232527947No ratings yet

- Beasts at Ephesus (A. J. Malherbe)Document11 pagesBeasts at Ephesus (A. J. Malherbe)sabioNo ratings yet

- Cynic Hero and Cynic King - Ragnar HoistadDocument238 pagesCynic Hero and Cynic King - Ragnar HoistadMarcos ViniciusNo ratings yet

- Demons and Dancers Performance in Late Antiquity (Webb, Ruth) (Z-Library)Document314 pagesDemons and Dancers Performance in Late Antiquity (Webb, Ruth) (Z-Library)JonathanNo ratings yet

- Bosman - Intellectual and Empire in Greco-Roman AntiquityDocument242 pagesBosman - Intellectual and Empire in Greco-Roman Antiquitypablosar86170No ratings yet