Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Biggs TheRoleOfTheWork2003

Uploaded by

nighbOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Biggs TheRoleOfTheWork2003

Uploaded by

nighbCopyright:

Available Formats

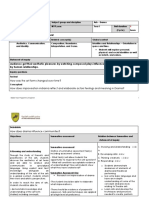

Parip/Practice as Research in Performance http://www.bris.ac.uk/parip/biggs.

htm

Note: This site is currently under construction

PA RIP 2003

N ATIO N AL C O N F E R E N C E: 11-14 S eptember

C O N T RIB U T O R S

BIG G S: MIC H A E L A R

faculty of art and design

university of hertfordshire

college lane

hatfield, herts. AL10 9A B

united kingdom

t: (0)1707 285341

f: (0)1707 285350

e: m.a.biggs @ herts.ac.uk

C opyright remains with the author(s). Do not quote from this webpaper without

written permission from the author(s).

th e rôle of ‘th e w ork’ in re s e arc h

K eywords including title: practice | museology | knowledge | context | text

K eywords excluding title: practice | rese arch | knowledge | 'the work' | text

a b stra ct

The paper opens with the definition of rese arch made by A H R B U K that art and

design rese arch must 'advance knowledge, understanding and insight'. The

paper goes on to consider the rôle of designed artefacts, art objects or

performance; 'the work', in communicating this advancement, and whether

'works' have the capability to embody knowledge. C omparisons are made with

archa eological and other museum exhibits, and criticisms of embodiment from

museological studies are compared with claims for embodiment made by artists.

The conclusion is that interpretation is a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic

factors, and that in order to communicate effectively control must be exercised

over the extrinsic factors by providing a context. Although commonly achieved

through words, this is owing to the utility of words for explicatory purposes rather

than because words have primacy over objects and performances in art and

design rese arch. It is therefore the content rather than the form of this context

1 von 9 16.2.2009 20:42 Uhr

Parip/Practice as Research in Performance http://www.bris.ac.uk/parip/biggs.htm

that is important. Arguments in favour of 'the work' as integral to practice-based

rese arch should therefore address how the context is managed to facilitate

effective communication through 'the work'.

Micha el Biggs is R e ader in Visual C ommunication and R ese arch Tutor in Art and

D esign at the University of H ertfordshire, U K. H e has degre es in both F ine Art

and Philosophy, and was S enior R ese arch F ellow in Philosophy at the University

of B ergen. His principal rese arch interest is in philosophical problems of

integrating images and text.

Let me open with an explanation of what I me an by 'the work' in this paper. I take

1 the term from the expressions 'a work of art' or 'a work of literature', etc. It refers

to an artefact, construed in the broad sense of an object, such as a sculpture or

painting, or something intangible such as an image, or something non-persistent

such as a performance. An artefact is anything 'man-made' in the non-gendered

sense. These 'works' are the outcomes of normal practice in the arts. However, 'a

work of art', etc. also connotes something that has achieved a certain cultural

status. Thus my focus is not on outcomes that are simply the product of art work of art and

classes, or that use art materials, and thereby become labelled as art; but rather socially

on outcomes of socially accredited value. The re ason for focussing on outcomes

accredited value

of socially accredited value is that the paradigm for arts rese arch is, I claim, a

work of artistic merit and a be arer of rese arch content. I do not believe that arts

rese archers are trying to argue in favour of two categories: artistic merit or artistic merit and

rese arch merit, but for one: artistic merit and rese arch merit. In the paper that research merit

follows I have therefore taken as my paradigm the case of the meritorious work

that also me ets the criteria for rese arch outcomes.

I shall begin this discussion by considering the consequences of a short but

important statement in the U K Arts and Humanities R ese arch Board's definition

of rese arch:

'The A H R B definition of rese arch provides a distinction betwe en rese arch and

3 practice per se . Cre ative output can be produced, or practice undertaken, as an AHRB

integral part of a rese arch process… but equally, cre ativity or practice may unterscheidet

involve no such process at all, in which case they would be ineligible for funding Praxis und

from the Board.'

Forschung

There are two elements to this statement. The first is the distinction betwe en

4 rese arch and practice. The second is the grounds for that distinction based on

certain defining characteristics of rese arch. A H R B identifies thre e groups of

characteristics:

it must define a series of rese arch questions that will be addressed or

problems that will be explored in the course of the rese arch. It must also Charakteristika

define its objectives in terms of answering those questions or reporting on der Forschung:

the results of the rese arch project

it must specify a rese arch context for the questions to be addressed or 1. Fragen und

problems to be explored. You must specify why it is important that these Anworten

particular questions should be answered or problems explored; what other

rese arch is being or has be en conducted in this are a; and what particular

contribution this particular project will make to the advancement of 2. Kontext

knowledge, understanding and insights in this are a

it must specify the rese arch methods for addressing and answering the 3. Methode

rese arch questions. You must state how, in the course of the rese arch

2 von 9 16.2.2009 20:42 Uhr

Parip/Practice as Research in Performance http://www.bris.ac.uk/parip/biggs.htm

project, you are going to set about answering the questions that have

be en set, or exploring the matters to be explored. You should also explain

the rationale for your chosen rese arch methods and why you think they

provide the most appropriate me ans by which to answer the rese arch

questions. Biggs'

Unterscheidung

I shall use these groups to make a distinction betwe en practice and rese arch. I zwischen

5 shall refer to them broadly as 'questions and answers', 'context' and 'methods'. Forschung und

Praxis:

Much attention has be en given to the third characteristic of 'methods' in the

1. Methode recent debate about rese arch in art and design, e.g. Durling & Friedman, 2000:

§§18-30. However, the principal fe ature of such rese arch is not the employment

Kunst verwendet

of a particular method but the desire or requirement to cre ate 'works' (i.e.

Objekte nicht als designed artefacts, art objects or performances) and to present them as part of

Beweise sondern the 'answer'. In this way, art and design rese arch is different from many other

als Teil der disciplines because it does not simply use objects as evidence which is later

Antwort auf die reported on, but attempts to present these objects as part of, or all of, an

Forschungsfrage argument for interpretation by the viewer. This implies the notion that 'the work'

can embody the answer to the rese arch question and this is one of the problems

that is considered in this paper.

2. Fragen und The first of the A H R B characteristics, 'question and answer', does not sit well with

art and design. Although the practitioner may set some particular problem as a

Antworten

motivation for work in the studio, most cre ative activity se eks to problematiz e that

which is familiar, or to raise questions or issues rather than to answer them.

Die Fragen der O utcomes ne ed to be interpreted rather than simply 're ad' and this undermines

their reception as putative answers. However, if these questions are rephrased

Kunst sind keine

as: 'how can X be problematiz ed?', 'how can Y be raised as an issue?', then I

Fragen sondern believe that 'question and answer' can have me aning in relation to cre ative

spezifische practice. This approach is not just peculiar to arts rese arch. Most humanities

Probleme. rese arch offers interpretations rather than answers to problems. This explains

why the same questions can ke ep recurring in humanities disciplines without

In den Humanities apparently ever being answered. To some extent they are unanswerable, which

sind die Antworten is perhaps what makes them into humanities questions in the first place. Also kann auch die

nur F urthermore, the approaches of humanities disciplines result in responses

Kunstantwort als

framed in terms of situated responses that have resonance in their time, but not

Interpretationen Interpretation

necessarily indefinitely. P erhaps if we consider humanities disciplines as offering

interpretations of problems inste ad of answers to questions then we might geltend gemacht

recognise something do-able in the 'question and answer' characteristic. werden.

This brings us to the last of the thre e A H R B characteristics: the contextualising

8 issue of why it is important that these particular questions should be answered or 3. Kontext

problems explored. This is sometimes another stumbling block, particularly to the

Romantic notion of the practitioner whose aim is the expression of the self. W e Ausdruck und

ne ed to differentiate betwe en activities that are to do with the personal

Selbstentwicklung

development of the practitioner and his or her cre ativity, and activities that are

significant for others in the field. It is only an activity that is significant for others

(Romantik) sind

that can be regarded as rese arch. P ersonal development does not make a nicht Forschung

contribution to the 'advancement of knowledge, understanding and insight',

except in the most parochial sense, i.e. my advancement. To illustrate this let us Nach AHRB: gilt

consider the discipline of arts therapies. It is the purpose of arts therapies to die Zielsetzung

improve the well-being of the client through an intervention involving the client des 'advancement

doing some kind of arts activity such as painting, music or drama, etc. Whether of knowledge,

the client produces art, in the sense of 'a work of art' mentioned above, is

understanding

irrelevant to the process. The activity is aimed at the personal development and

self knowledge of the individual and not at the advancement of knowledge, and insight'

understanding and insight into some issue shared by others. O f course, the

3 von 9 16.2.2009 20:42 Uhr

Parip/Practice as Research in Performance http://www.bris.ac.uk/parip/biggs.htm

client's case may contribute to the advancement of knowledge in arts therapies,

but this would be an outcome for the therapist and not for the client. In addition, Biggs sieht also

the client's productions may subsequently achieve the status of 'works' but this 3 Kategorien

would be incidental to their original function in connection with improved von Kunst:

well-being. Thus I would distinguish betwe en (1) art as therapy (for the Kunst als

individual), (2) art as cultural practice (the production of works of art), and (3) art

as rese arch (me eting certain criteria under discussion). It is my claim that (1) and

Therapie, Kunst

(3), that is, art as therapy and art as rese arch, are mutually exclusive. I should als kulturelle

emphasise that this does not me an that I deny that there is such a discipline as Praxis und

arts therapies rese arch! Kunst als

Forschung

O ne might argue that (1) is a prerequisite for (2) and (3) because it is only if one

9 develops as a practitioner that one can re ach the level at which one can make a

cultural and/or rese arch contribution of significance. However, the definition of

'the work' and the definition of rese arch determine that it is only when the

outcomes are directed towards public consumption that they become (2) art as

cultural practice and/or (3) art as rese arch. To this extent, if the agenda of

production is personal development as a precursor to the production of significant

public outcomes, then it might better be described as motivation or

self-development rather than therapy.

Anticipating whether an activity will be significant for others is not a matter of

clairvoyance. P art of the process of identifying the context involves finding out

'what other rese arch is being or has be en conducted in this are a'. Making a

further contribution would therefore be significant to at le ast this group of

co-rese archers. Moreover, there may be an educational, theoretical, critical, or

practical context for which there is an audience who should also find the

outcomes significant. Note that the mode is obligatory: 'should' or 'ought to' find

the outcomes significant. The task of identifying 'why it is important that these

particular questions should be answered or problems explored', and for whom,

cannot be answered by saying that this group will find the outcomes significant,

but by supplying an argument that shows that they ought to find it significant.

There is one further matter concerning the audience and that is its siz e. Many

11 rese archers have the ide alistic notion that to be worthy of the name, rese arch

must have a large impact. Inde ed, in the U S A, rese arch publications are

assessed in terms of the relative importance or impact-rating of journals and the

number of times an item is cited by another rese archer. We have a similar notion

in art and design, rating the value of a performance in the N ational T he atre

higher than one in the village hall. O ne part of this assumed value is the rigour of

the selection process. We do not value the latter because its lesser impact is a

product of the we aker selection process. But another is the audience siz e:

performances in the N ational The atre re ach both a larger and a more distributed

audience. A useful question that may be asked in order to ensure that a rese arch

project me ets the 'why' characteristic of the contextual question is 'who is the

target audience?' Answering this question identifies the number and location of

the audience and facilitates targeting the outcomes of the rese arch in the

appropriate venues, journals, etc.

The issue of the communication and dissemination of the outcomes is also an

12 important factor for funding agencies such as A H R B, although it is not one of Distribution und

their 3 indicators. O ne might regard it as implied in the notion of making a Kommunikation

contribution since the contribution will go unnoticed if it is not communicated. If der F-Resultate

we believe that 'the work' has the capacity to communicate the 'knowledge, sind wichtig für

understanding and insights in this are a', then we have a tacit notion of the die AHRB. Also

embodiment of knowledge in objects and performances. But we should first be

auch das

sceptical and ask 'can such works embody knowledge, and if so, how?' Since this

Wissen, das in

den Objekten

4 von 9

oder

16.2.2009 20:42 Uhr

Performances

verkörpert ist.

Parip/Practice as Research in Performance http://www.bris.ac.uk/parip/biggs.htm

capacity of 'the work' to embody knowledge is problematiz ed in this paper, I Biggs behandelt

propose that, methodologically, we examine the embodiment of knowledge in nun das embodied

artefacts from the point-of-view of museum studies, and then consider whether knowledge anhand

this case study is transferable to art and design rese arch. des Paradimgas

13 Museum.

Vorliteralisierte Most of the knowledge that we have of pre-literate societies comes from the

Gesellschaften- interpretation of archa eological 'works' that have survived. However, key aspects

of the argument are speculative. Let me take as an example the cave paintings at

Archäologie, Lascaux. O pinion is divided about whether the paintings show a hunting

Lascaux => Die expedition or represent a ritual activity in which image-animals are slaughtered

Interpretation der symbolically as an auspicious prelude to the actual hunt. The re ason that this

Malereien ist nicht important distinction cannot be reliably made is because the images do not

möglich, weil ihr embody information about their use, i.e. whether it is depictive or symbolic. This

Kontext des is not a problem confined to objects of gre at antiquity. F or example, there is little

material difference betwe en a pair of chop-sticks and a pair of knitting-ne edles

Gebrauchs nicht except the cultures in which they are found and the way in which they are used.

bekannt ist. This is even more apparent if one considers that there is nothing about their

physical form that prevents them being exchanged and the one used for the

purpose of the other.

14

Der Parthenon- Let us consider another more complex example. The P anathenaic frie z e depicts

frieze: Unbekannt, the quadrennial procession through Athens to the Acropolis in the fifth century

was der Gebrauch B C . The frie z e originally adorned the P arthenon where its reception and its

signification in relation to the accompanying performance in the view of ancient

im 5. J. V.u.Z war.

Athenians cannot be exactly known. When Lord Elgin removed part of this frie z e

Nach Elgin wurde to London at the beginning of the ninete enth century some of its me aning

die Bedeutung certainly changed. As a 'souvenir of the Grand Tour' it became the subject of

jedoch geändert. a esthetic appreciation and was displayed accordingly for the benefit of

connoisseurs. As a surviving artefact from antiquity it took on the role of

representing the performance and embodying and a estheticising our knowledge

of it. In the twentieth century the so-called Elgin marbles became the subject of

Die Bedeutung ist post-colonial arguments about the ownership of cultural 'works' and their

nicht in den Dingen appropriation. Issues of colonialism came to be se en as embodied in these

(Formalismus) marbles in a way that was not previously apparent. What then is embodied in the

frie z e per se ? The fact that these different interpretations have come about with

sondern:

the passage of time suggests that while F ormalists claim there are qualities in the

frie z e put there by Phidias, some of the me anings are extrinsic, being projected

onto them through the culture or the way in which they are exhibited. T his is a

product of the physical properties that objects possess, and the way in which we

classify and use them, e.g. this is symbolic, this is be autiful, this is stolen, etc.

We should be familiar with the way in which our classification of objects affects

15 our understanding of them, and the knowledge that they embody. F oucault, in

The Order of Things and The Archa eology of Knowledge , sustained a critique

against our assumption that there are natural or obvious categories of objects in

the world. The whole notion of F oucault's 'epistemes', or inde ed Kuhn's 'paradigm

shifts', involves a change not in the nature of the external world, but in the

perceived relationship of its parts, or the changing belief that some elements are

more significant than others. Arguments and assumptions that are raised as a

consequence of the analysis of objects must therefore, post-F oucault, include an

account of the classificatory approach towards objects that allows that argument

to be sustained. Problematizing relationships and questioning implicit

assumptions is a common activity in rese arch.

The fact that objects can be included in an infinite number of different taxonomies

shows that their rationale for inclusion or exclusion is not embodied in the objects

themselves. This is one re ason why one cannot have a rese arch outcome that

5 von 9 16.2.2009 20:42 Uhr

Parip/Practice as Research in Performance http://www.bris.ac.uk/parip/biggs.htm

consists solely of 'works', e.g. paintings, because the relationships betwe en the

Forschungsresultat paintings themselves, and betwe en the paintings and other 'works' or activities in

e können nicht the world, is not intrinsic to the objects. O bjects or performances, etc. may have Wollheim's

ausschliesslich aus inter-textual references but that does not imply that the nature of the relationship (Philosophie der

Werken bestehen, alluded to is made explicit. E mbodiment is what Wollheim (1980: §4) calls the Gefühle, C.H.

'physical-object' hypothesis, which he refutes partly on the grounds of our ability

weil das Verhältnis Beck 2001)

to project interpretative values: his key notion of 'se eing-in'. In the context of the

zur Welt den present conference, there is no re ason to suppose that the physical-object physical-object-

Werken nicht hypothesis is not transferable to performances. Hypothese:

eingeschrieben ist.

The physical-object hypothesis is implicit in exhibitions and performances where

17 objects are left to spe ak for themselves. Vergo (1989: 48) contrasts such

'a esthetic' exhibitions with 'contextual' exhibitions. A esthetic exhibitions and

performances have little additional information other than the artefacts Peter Vergo, The

themselves, and the process of understanding them is largely experiential. In New Museology,

contextual exhibitions and performances the artefacts are complementary to

unterscheidet

some accompanying 'informative, comparative and explicatory' material. Vergo is

critical of the a esthetic view wherein artefacts putatively embody knowledge, not 'aesthetic' und

le ast because viewers may not share the same social and cultural background on 'contextual'

which the interpretation of the artefacts depends. More importantly, what one Austellungen

knows contextually about the artefact, or what one is told, affects one's re ading or

interpretation of it, e.g. this is valuable, this is poisonous, this is a fake, etc. B eing

told nothing is not a neutral stance, but simply allows the viewer to project his or

her prejudices onto the artefact. In a esthetic exhibitions the author therefore has

no control over the artefact's reception. If the aim of rese arch is to communicate

knowledge or understanding then reception cannot be an uncontrolled process.

The interpretation of embodied knowledge presented in an uncontextualised way

is an uncontrolled process.

This notion of projecting values and altering the passive notion of se eing into the

18 active notion of interpretation, has a long history, e.g. Wollheim's concept of seeing-in

'se eing-in' and Wittgenstein's concept of 'se eing-as'. C oupled with the thirty ye ars (Wollheim) und

that have be en available to appreciate F oucault's arguments against natural seeing-as

taxonomies, it should hardly ne ed emphasising that the process of visual (Wittgenstein)

communication and interpretation cannot rely upon 'works' alone (Hooper-

Gre enhill, 1992: 1-22). It is mentioned here because there is still a rump of

practitioners who advocate the 'a esthetic' position but who, perhaps as a

consequence of their beliefs, have failed to provide a satisfactory counter-

argument.

The interim conclusion I would like to draw from the above observations is that

Biggs folgert: 19 our reception of artefacts and performances depends on a combination of

intrinsic and extrinsic aspects. Interpretation is an intentional act, in the

phenomenological sense of actively cre ating a perception. It is not always cle ar

which aspect is at work at any one time, and novel interpretations often draw

attention to aspects that are implicit about which we were not previously aware.

F or example, the colonial attitudes we now se e as explicit in the 1816 London

exhibition of the so-called Elgin marbles were probably not so apparent to the

ninete enth century audience celebrating their supposed rescue from destruction

by the O ttomans.

There is another observation that we can draw from the new museology. It is a

gre ater awareness of the effect that the venue and the juxtaposition with

contextualising material has on our interpretation of 'works'. O ur interpretation

can be actively manipulated by the way in which 'works' are displayed. Inde ed

the whole notion of display then becomes problematic because 'non-display' can

be se en as a particular intervention. How can we differentiate betwe en the

6 von 9 16.2.2009 20:42 Uhr

Parip/Practice as Research in Performance http://www.bris.ac.uk/parip/biggs.htm

elements of our interpretation that are determined by the juxtaposition and

presentation of 'the work' in relation to others, and those aspects that are

embodied in 'the work' itself? What is the unmediated content of 'the work'?

F or the purposes of this paper I do not think I ne ed to argue that there is nil

Null embodiment embodiment of knowledge in 'works'. It is sufficient to show that the context

of knowledge in affects our re ading of 'the work' in order to demonstrate that 'works' alone cannot

the 'works' ! embody knowledge. This situation is comparable to the me aning of individual

words. Although most of us have be en taught that one way to approach an essay

question is to se ek the dictionary definitions of key terms in the question, we are

20

also familiar with the fe elings of dissatisfaction that arise from these isolated

definitions. Words have me anings in the context of sentences, alongside other

words, and in social contexts in which utterances are accompanied by actions.

So it is that individual objects and performances devoid of context become

more-or-less devoid of me aning. Likewise, as they become contextualised they

become more-or-less me aningful. F urthermore, we are aware that the

interpretation of words and of works of literature, changes over time owing to

changes in the intertextual context. F or example, in 1920 James Joyce's Ulysses

was denounced as 'obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, indecent and disgusting' by

the N ew York Society for the Suppression of Vice, but by 1941 it was hailed by

Levin as 'a novel to end all novels' (Joyce 1993: xli & ix). This shows that words

or texts do not have single unalterable me anings any more than do 'works'. T his

forms a counter-argument to those who object to the outcomes of art and design

rese arch being a combination of 'works' and words/texts on the grounds that it

gives words/texts primacy over 'works': the so-called 'heresy of paraphrase'

(Wollheim 1980: §49). O n the contrary, it is the particular combination of 'works'

and words/texts that gives efficacy to the communication. N either 'works' alone

nor words/texts alone would be sufficient. What is required is the combination of

'the work' [painting, design, poem, dance, etc] and a critical exegesis that

describes how it advances knowledge, understanding and insight, i.e. its

instrumentalism.

There is also an ontological issue in the performing arts concerning the

relationship of the notation to the performance. W e expect there to be a

difference betwe en the work as annotated in a score, etc., and the performance

of that work, which is an interpretation of the score. O n the other hand, in a work

of rese arch we would expect the rese archer to be unambiguous about both the

evidence and argument, and the conclusions. The model for performance always

incorporates this notion of interpretation, but it is the interpretation of the

performer not the interpretation of/by the composer, etc. So whose work of

rese arch is it? If we took as an extreme case a form of notation that completely

fixed the form of a performance of a piece of music so that all performances were

the same, e.g. the player-piano, we would probably not consider that playing the

music was any longer a performance rather than a document (Stravinsky

1975:150). This is not a problem confined to the performing arts but to any form

of presentation that gives scope for interpretation at the point of consumption.

Now it might be argued that all forms of reception are interpretive, but I think one

can se e that traditional rese arch papers are written in such a way as to be as

unambiguous as possible, that is, to minimise the effect of re ader-interpretation

where as poetry for example, is written to maximise it.

The interpretation of a work is not determined solely by intrinsic factors, but

depends, to a gre ater or lesser extent, on the context in which the interpretation

takes place: the point-of-view and the critical and cultural apparatus that the

viewer brings to be ar on the artefact or performance. Given these conditions, is

there anything that we can do to incre ase the role played by the work? C ould we

describe a situation in which the intrinsic factors were maximised and the

7 von 9 16.2.2009 20:42 Uhr

Parip/Practice as Research in Performance http://www.bris.ac.uk/parip/biggs.htm

extrinsic factors were minimised? I think the response to that has to be 'yes'. In

saying that the contextual presentation is one in which there is an attempt to

control the conditions under which the interpretation is undertaken we are also

saying that the contextual presentation contains elements that militate against

interpretation. So if we wish to minimise these extrinsic factors we must try to

incorporate some of the function that they perform into the work itself.

If we return to the museum artefact as a paradigm case, there are several points

23 that immediately stand out as influencing the viewer's interpretational strategy.

These include venue, the presentation or exhibition, the nature of the

accompanying information, and the socio-cultural positioning of the activity of

museum-visiting, The venue itself isolates the experience: entering the museum

is not something one normally does by accident. There are cues in the

geographical location, the architectural experience, the experience of entering

and navigating the physical spaces. It cues us to the kind of experience we are

about to have: a good time, an education, being bored, etc. The presentation or

exhibition of the artefacts, possibly in glass cases, possibly with armed guards,

le ads us to appreciate these artefacts in ways that are distinct from the

appreciation of similar artefacts in everyday situations: 'in the hermetically se aled

case' as contrasted with 'in the washing-up bowl'. The accompanying information

suggests an interpretational frame of reference that guides our appreciation in

ways preferred by the curator: 'the last painting by Van G ogh before he killed

himself', '…priceless', '…forged', etc. The socio-cultural position adopted by us

may be by virtue of our education, of our social ambitions, our revolutionary

contempt, etc.

When the 'Jade Suit' was exhibited at the Royal Academy in London in 1980s

there were huge queues to se e this object from the C 2B C . When I saw the

artefact in its usual dusty display case in the N anjing Museum in 1990, nobody

was interested in the object precisely because it was from the C 2B C . If we se ek

to transfer these extrinsic contextualising factors to the artefact we must find a

way of providing the viewer with this information through the vehicle of the work.

In this regard, performances have an advantage because they are time-based.

25 This allows a narrative to be constructed that takes the audience through a

developmental process, modifying their perception. Whether this can be done by

the same performance that we wish to prepare the audience to receive is another

matter. I suspect it cannot: that we are describing a preparatory process that may

be undertaken by me ans of a performance followed by the performance over

whose interpretation we wish to have gre ater control.

What is the consequence of this argument for the role of 'the work' in rese arch?

26 We have se en that the artefact cannot be relied upon to communicate in

isolation. It may be that several artefacts in juxtaposition can cre ate a situation in

which me anings are constructed and communicated, but in such cases it

becomes part of the rese arch question to account for how such configurations

can be manipulated so as to communicate the outcome. This necessitates the

unpacking of the way in which these artefacts operate and in turn generates

contextual material. This contextualising is most likely to be expressed in words

although I am open to persuasion that it can be done in another medium. Words

are simply an efficient me ans of establishing a context. They do not have any

primacy over 'works', nor is the contribution of works made redundant by words.

What is essential is not a particular medium but a particular content , i.e. it must

step outside the outcomes of the rese arch and explicate the way in which the

rese arch embodies its 'contribution… to the advancement of knowledge,

understanding and insight.'

8 von 9 16.2.2009 20:42 Uhr

Parip/Practice as Research in Performance http://www.bris.ac.uk/parip/biggs.htm

R eferences

- Arts and Humanities R ese arch Board. G uidance notes. http://www.ahrb.ac.uk/

[2003]

Durling, D. & K. Friedman (eds.) (2000) Doctoral E ducation in D esign:

foundations for the future , Stoke-on-Trent, U K: Staffordshire University Press.

F oucault, M. [1966] (1974a) The Order of Things , London: Tavistock Press.

F oucault, M. [1969] (1974b) The Archa eology of Knowledge , translated by A.M.

Sheridan Smith, London: Tavistock Press.

Hooper-Gre enhill, E . (1992) Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge , London:

Routledge.

Joyce, J. [1922] (1993) Ulysses , London: O xford University Press.

Kuhn, T. [1962] (1970) The Structure of Scientific R evolutions , second edition,

London: University of C hicago Press.

Stravinsky, I. (1975) An Autobiography . London: C alder and Boyars.

Vergo, P. (ed.) (1989) The N ew Museology , London: R e aktion Books.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953) Philosophical Investigations , O xford: B asil Blackwell.

Wollheim, R. [1968] (1980) Art and its O bjects , second edition, London:

C ambridge University Press.

B ack to main conference page

9 von 9 16.2.2009 20:42 Uhr

You might also like

- Research in Art and Design: Research Problems, Programmes and DatabasesDocument11 pagesResearch in Art and Design: Research Problems, Programmes and DatabasessuhailNo ratings yet

- Proposal Writing Workshop - Notes IncludedDocument27 pagesProposal Writing Workshop - Notes IncludedAsmaa ZedanNo ratings yet

- 5 Reflective Practice and Experiential KnowledgeDocument17 pages5 Reflective Practice and Experiential KnowledgeDương ĐăngNo ratings yet

- Philosophy 25 Homework Assignment 2Document7 pagesPhilosophy 25 Homework Assignment 2Laurel WeberNo ratings yet

- Obtl Art AppreciationDocument7 pagesObtl Art AppreciationGillian GabardaNo ratings yet

- JVAPFiring Practice 2002Document13 pagesJVAPFiring Practice 2002phungthulanNo ratings yet

- Defining Computational Aesthetics HoenigDocument6 pagesDefining Computational Aesthetics HoenigVictor OkhoyaNo ratings yet

- Project Proposal Form Foundation Unit 4Document5 pagesProject Proposal Form Foundation Unit 4api-544739000No ratings yet

- Project Proposal Form Foundation Unit 4Document5 pagesProject Proposal Form Foundation Unit 4api-544739000No ratings yet

- Project Proposal Form Foundation Unit 4Document5 pagesProject Proposal Form Foundation Unit 4api-544174107No ratings yet

- Felix Coates Observation and Making Feedback FormDocument4 pagesFelix Coates Observation and Making Feedback Formapi-637557541No ratings yet

- Arts ActivitiesDocument115 pagesArts ActivitiesJames CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Beyond Reading and Mathematics Test Scores: Arts - and Science-Related MeasuresDocument10 pagesBeyond Reading and Mathematics Test Scores: Arts - and Science-Related Measureswested-magnet-schoolsNo ratings yet

- Niedderer Biggs Ferries Research Exhibition 2006Document15 pagesNiedderer Biggs Ferries Research Exhibition 2006nighbNo ratings yet

- Ok Practice-Based Research PDFDocument7 pagesOk Practice-Based Research PDFKostas DaflosNo ratings yet

- How To Do A Thesis: Practice Models As Instigators For Academic ThesesDocument6 pagesHow To Do A Thesis: Practice Models As Instigators For Academic ThesesflipschitzNo ratings yet

- Juliet Project Proposal FMPDocument6 pagesJuliet Project Proposal FMPapi-543399755No ratings yet

- Learning Activity Sheet (Las) in Cpar (4: Quarter)Document15 pagesLearning Activity Sheet (Las) in Cpar (4: Quarter)hellohelloworld0% (1)

- Archer Bruce - Design As A DisciplineDocument4 pagesArcher Bruce - Design As A DisciplineHarshmita SinghNo ratings yet

- 1a. A Thesis (Mark Jarzombek) : Subjective Fantasy and Architecture As An Intellectual DiscourseDocument3 pages1a. A Thesis (Mark Jarzombek) : Subjective Fantasy and Architecture As An Intellectual DiscourseTamaraNo ratings yet

- Lit Review SampleDocument8 pagesLit Review SamplemuskaanNo ratings yet

- Evolutionary Design: Philosophy, Theory, and Application TacticsDocument6 pagesEvolutionary Design: Philosophy, Theory, and Application TacticsjerryNo ratings yet

- A Tacit Understanding The Designer's Role in Capturing and Passing On The Skilled Knowledge of A Master CraftsmenDocument14 pagesA Tacit Understanding The Designer's Role in Capturing and Passing On The Skilled Knowledge of A Master CraftsmenLuther JimNo ratings yet

- A Pedagogy of PoiesisDocument12 pagesA Pedagogy of PoiesisKhairi BaharomNo ratings yet

- Hall - 2010 - Making Art, Teaching Art, Learning Art ExploringDocument8 pagesHall - 2010 - Making Art, Teaching Art, Learning Art ExploringAlexandra NavarroNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Performance PDFDocument8 pagesContemporary Performance PDFAdrianneNo ratings yet

- Art Appreciation: College of Liberal Arts Department of LiteratureDocument6 pagesArt Appreciation: College of Liberal Arts Department of Literaturekean ebeoNo ratings yet

- MYP Unit Plan - Yr3 DramaDocument10 pagesMYP Unit Plan - Yr3 DramaLudwig Santos-Mindo De Varona-LptNo ratings yet

- Sample Title of Thesis Project Goes Here: A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements of TheDocument15 pagesSample Title of Thesis Project Goes Here: A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements of TheAlaine Dominique GumeraNo ratings yet

- Assessment Creation 19189518 Brigitte GergesDocument11 pagesAssessment Creation 19189518 Brigitte Gergesapi-374378404No ratings yet

- IJAR, Vol. 4 - Issues 23 - July-November 2010 Towards Total Integration in Design StudioDocument10 pagesIJAR, Vol. 4 - Issues 23 - July-November 2010 Towards Total Integration in Design StudiomoonnaNo ratings yet

- The Architectural ReviewDocument18 pagesThe Architectural ReviewSegher de ReijNo ratings yet

- PHD ProposalDocument5 pagesPHD ProposalRupam Pathak100% (1)

- Schubert - SwitchingWorlds - Englisch (Dragged) 5Document3 pagesSchubert - SwitchingWorlds - Englisch (Dragged) 5Isandro Ojeda GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Reviews: Performance Perspectives: A Critical IntroductionDocument6 pagesReviews: Performance Perspectives: A Critical IntroductionunocienNo ratings yet

- Mission: Program Curriculum Ay 2020 - 2021Document9 pagesMission: Program Curriculum Ay 2020 - 2021beaNo ratings yet

- Theatre Analysis: Some Questions and A Questionnaire: Patrice PavisDocument5 pagesTheatre Analysis: Some Questions and A Questionnaire: Patrice Paviskevinbrazil100% (2)

- Art and Design and Design and Technology Is ThereDocument16 pagesArt and Design and Design and Technology Is ThereKARMA NEGINo ratings yet

- Paradigm Shift in Design PraxisDocument7 pagesParadigm Shift in Design PraxisindesignbureauNo ratings yet

- Guide To Writing A Synopsis PDFDocument5 pagesGuide To Writing A Synopsis PDFIndujaa PadmanaabanNo ratings yet

- Visual Rhetoric: A Situated IntroductionDocument5 pagesVisual Rhetoric: A Situated IntroductionMuhammad AmerNo ratings yet

- Part 3 Ex 2019 Rosage Ib JhsDocument1 pagePart 3 Ex 2019 Rosage Ib Jhsapi-250972257No ratings yet

- Visual Development 1 - May23Document4 pagesVisual Development 1 - May23sajeevj98No ratings yet

- Gupea 2077 22775 1Document98 pagesGupea 2077 22775 1ar.ryanortigasNo ratings yet

- Communicating Creativity The Discursive Facilitation of Creative Activity in Arts 1St Edition Darryl Hocking Auth Full ChapterDocument68 pagesCommunicating Creativity The Discursive Facilitation of Creative Activity in Arts 1St Edition Darryl Hocking Auth Full Chapterlisa.gomez339100% (7)

- Ge Aa Art Appreciation ModuleDocument89 pagesGe Aa Art Appreciation ModuleRamilyn Villarido ChiongNo ratings yet

- C P - G A U: Adernos de ÓS Raduação em Rquitetura E RbanismoDocument16 pagesC P - G A U: Adernos de ÓS Raduação em Rquitetura E RbanismoaadqdmbNo ratings yet

- MYP Unit Plan - Grade 10Document10 pagesMYP Unit Plan - Grade 10Ludwig Santos-Mindo De Varona-LptNo ratings yet

- Graphic Communication BA4 Project 1Document4 pagesGraphic Communication BA4 Project 1Owen MelbourneNo ratings yet

- Re Ections On The Genre of Philosophical Art Installations: Erik Rietveld and Julian KiversteinDocument14 pagesRe Ections On The Genre of Philosophical Art Installations: Erik Rietveld and Julian KiversteinJacopo FrascaroliNo ratings yet

- MYP Unit Plan - Yr1 DramaDocument10 pagesMYP Unit Plan - Yr1 DramaLudwig Santos-Mindo De Varona-Lpt100% (3)

- pr1 Lesson 4Document3 pagespr1 Lesson 4Krystel Tungpalan100% (1)

- Extended Essay in Visual Arts StudentsDocument9 pagesExtended Essay in Visual Arts Studentsapi-279889431No ratings yet

- May 24 Art PcupDocument3 pagesMay 24 Art Pcupaanyadhingra94No ratings yet

- Teaching Art and DesignDocument14 pagesTeaching Art and DesignWilliamNo ratings yet

- G10 Q1 Arts Module 7Document6 pagesG10 Q1 Arts Module 7Manuel Rosales Jr.100% (1)

- PR1 Lesson 4 FinalDocument6 pagesPR1 Lesson 4 FinalKrystel TungpalanNo ratings yet

- Thesis ArtisticaDocument7 pagesThesis ArtisticaBuyPapersForCollegeAlbuquerque100% (2)

- Week 1 Introduction and Research Questions 1Document5 pagesWeek 1 Introduction and Research Questions 1Sơn Hồ ThanhNo ratings yet

- Peering Into The Fog of War: The Geography of The Wikileaks Afghanistan War Logs, 2004-2009Document24 pagesPeering Into The Fog of War: The Geography of The Wikileaks Afghanistan War Logs, 2004-2009nighbNo ratings yet

- 2011-07-09 - Is Assange The Quotworld-Spirit Embodiedquot A Hegel Scholar Reports From The IekAssange Troxy GigDocument3 pages2011-07-09 - Is Assange The Quotworld-Spirit Embodiedquot A Hegel Scholar Reports From The IekAssange Troxy GignighbNo ratings yet

- Manning-Lamo Chat Logs Revealed - Threat Level - WiredDocument78 pagesManning-Lamo Chat Logs Revealed - Threat Level - WirednighbNo ratings yet

- Upheaval As PhilosophyDocument7 pagesUpheaval As PhilosophyBong ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Wikileaks and The New Language of DiplomacyDocument7 pagesWikileaks and The New Language of DiplomacynighbNo ratings yet

- Boris Groys: Art and MoneyDocument9 pagesBoris Groys: Art and MoneynighbNo ratings yet

- Truth As Formal Catholicism - On Alain Badiou, Saint Paul: La Fondation de L'universalismeDocument25 pagesTruth As Formal Catholicism - On Alain Badiou, Saint Paul: La Fondation de L'universalismenighbNo ratings yet

- Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004Document236 pagesIntelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004nighbNo ratings yet

- Objective of This Lecture: To Introduce Theorizing On The Body in ArtDocument27 pagesObjective of This Lecture: To Introduce Theorizing On The Body in ArtnighbNo ratings yet

- 2006 UCC SyllabusDocument8 pages2006 UCC SyllabusnighbNo ratings yet

- IrisDocument1 pageIrisnighbNo ratings yet

- Vcs 06 PhotographyDocument24 pagesVcs 06 PhotographynighbNo ratings yet

- Objectives of This Lecture:: Topic 11 BenjaminDocument23 pagesObjectives of This Lecture:: Topic 11 BenjaminnighbNo ratings yet

- AlchemyDocument3 pagesAlchemynighbNo ratings yet

- Topic 7 Space, Form, Realism: Objectives of This LectureDocument9 pagesTopic 7 Space, Form, Realism: Objectives of This LecturenighbNo ratings yet

- Topic 8 Time, Narrative: Objectives of This LectureDocument6 pagesTopic 8 Time, Narrative: Objectives of This LecturenighbNo ratings yet

- Issues in Visual and Critical Studies: Survey of The Course: A. Principal Themes B. Objectives of The CourseDocument22 pagesIssues in Visual and Critical Studies: Survey of The Course: A. Principal Themes B. Objectives of The CoursenighbNo ratings yet

- 6 ConclusionsDocument8 pages6 ConclusionsnighbNo ratings yet

- Revising Step of Research PaperDocument2 pagesRevising Step of Research Papersajal munawarNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Strategy: Thomas C. Powell, Dan Lovallo, and Craig R. FoxDocument18 pagesBehavioral Strategy: Thomas C. Powell, Dan Lovallo, and Craig R. FoxUganesvari MuthusamyNo ratings yet

- Hilary Putnam - Philosophy of LogicDocument16 pagesHilary Putnam - Philosophy of Logicmihail_clementNo ratings yet

- EapDocument4 pagesEapDayhen Afable Bianes0% (1)

- Extracts - Life of Fr. CavinaDocument6 pagesExtracts - Life of Fr. CavinaSr. Lyn SabalzaNo ratings yet

- Zizek, Slavoj - Passion in The Era of Decaffeinated BeliefDocument6 pagesZizek, Slavoj - Passion in The Era of Decaffeinated BeliefIgor Viana MüllerNo ratings yet

- Nature of ManDocument23 pagesNature of ManJade Harris' SmithNo ratings yet

- Exploration of Chinese Ecological and Environmental PhilosophyDocument4 pagesExploration of Chinese Ecological and Environmental PhilosophyBezaleel ThomasNo ratings yet

- Scalia Teaching About The LawDocument6 pagesScalia Teaching About The LawIlia BadzaghuaNo ratings yet

- Romanticism - TranscendentalismDocument24 pagesRomanticism - TranscendentalismRangothri Sreenivasa SubramanyamNo ratings yet

- Hegemony & Ideology by Raymond Williams (From Keywords)Document7 pagesHegemony & Ideology by Raymond Williams (From Keywords)Deidre Morales100% (1)

- Definitions 6 Austin's Command Theory of Law ......................... 7 Sovereignty ..8Document12 pagesDefinitions 6 Austin's Command Theory of Law ......................... 7 Sovereignty ..8Adv BL DewasiNo ratings yet

- UNESCO 2007: Philosophy A School of FreedomDocument303 pagesUNESCO 2007: Philosophy A School of Freedomdiegochillo5506100% (1)

- Literary Criticism The Formal Approach To LiteratureDocument19 pagesLiterary Criticism The Formal Approach To LiteratureThessalonica BergmanNo ratings yet

- Methods of Acquiring Knowledge OverDocument14 pagesMethods of Acquiring Knowledge Overbalusa95% (22)

- Panofsky Reflection PaperDocument1 pagePanofsky Reflection PapertrishaandreidNo ratings yet

- RizalDocument2 pagesRizalJean23No ratings yet

- Schelling F.W.J. The Concept of Absolute Knowledge Ch. 1 of On University StudiesDocument12 pagesSchelling F.W.J. The Concept of Absolute Knowledge Ch. 1 of On University StudiesnaomiNo ratings yet

- Assignment 01 CC-0695Document11 pagesAssignment 01 CC-0695Ghazal MunirNo ratings yet

- Theravada BuddhismDocument2 pagesTheravada BuddhismChelsea EspirituNo ratings yet

- Ethnomethodology and EthnosociologyDocument19 pagesEthnomethodology and Ethnosociology王聪慧No ratings yet

- PDFD - Work Central Issues Translations Semantics PDFDocument5 pagesPDFD - Work Central Issues Translations Semantics PDFBerkay BocukNo ratings yet

- Unit 3: Development Stages in Middle and Late AdolescenceDocument17 pagesUnit 3: Development Stages in Middle and Late AdolescenceJonthegeniusNo ratings yet

- Can We Chose Our Own Identity AnalysisDocument2 pagesCan We Chose Our Own Identity Analysisapi-467610075No ratings yet

- Some Remarks On The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, Written by Mr. William Shakespeare (1736) by AnonymousDocument43 pagesSome Remarks On The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, Written by Mr. William Shakespeare (1736) by AnonymousGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Elc 121 Intro To LiraDocument9 pagesElc 121 Intro To LiraPutri Nur SyahzatulNo ratings yet

- PancikaranaDocument1 pagePancikaranamal_sri6798No ratings yet

- René Descartes Biography: Quick FactsDocument13 pagesRené Descartes Biography: Quick FactsAngela MiguelNo ratings yet

- ENTREVISTA COM Paul Duncum, - Por Joao FroisDocument9 pagesENTREVISTA COM Paul Duncum, - Por Joao FroisMagali MarinhoNo ratings yet

- Grow Taller Bonus Report 20Document2 pagesGrow Taller Bonus Report 20diegoNo ratings yet