Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Principles of Translation

Uploaded by

Wenxin Huang0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

139 views2 pagesseven principles of translation

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentseven principles of translation

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

139 views2 pagesPrinciples of Translation

Uploaded by

Wenxin Huangseven principles of translation

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

5 Principles of translation

Although this is not a theoretical work, I realize that teachers may

appreciate some guidelines on how to help the students evaluate

their own work. Specific remarks are given in the Comments'after

each activity. Below are some general principles which are relevant

to all translation:

a. Meaning. The translation should reflect accurately the meaning

of the original text. Nothing should be arbitrarily added or

removed, though occasionally part of the meaning can be

'transposed', for example, He was limp with fatigue might

become: Il tait tellement fatigu qu'llne tenait plus debout.

Ask yourself:

- is the meaning of the original text clear? if not, where does the

uncertainty lie?

- are any words 'loaded', that is, are there any underlying

implications? ('Correct me if I'm wrong . . .' suggests 'I

know I'm right'!)

- is the dictionary meaning of a particular word the most

suitable one? (should suboerzijabe suboersion in English?)

- does anything in the translation sound unnatural or forced?

b. Form. The ordering of words and ideas in the translation should

match the original as closely as possible. (This is particularly

important in translating legal documents, guarantees, contracts,

etc.) But differences in language structure often require changes

INTRODUCTION

in the form and order of words. \7hen in doubt, underline in the

original text the words on which the main stress falls. (See

activities 1.3,.2.I, and 2.2.)

c. Register. Languages often differ greatly in their levels of

formality in a given context (say, the business letter). To resolve

these differences, the translator must distinguish between

formal or fixed expressions (le oous prie, madame, d'agrer

I'expression de mes sentiments distingus, or Please find

enclosed . . .) and personal expressions, in which the writer or

speaker sets the tone.

Consider also:

- would any expression in the original sound too formal/

informal, cold/warm, personal/impersonal . . . if translated

literally?

- what is the intention of the speaker or writer? (to persuade/

dissuade, apologize/criticize?) Does this come through in the

translation?

d. Source language influence. One of the most frequent criticisms of

translation is that 'it doesn't sound natural'. This is because the

translator's thoughts and choice of words are too strongly

moulded by the original text. A good way of shaking off the

source language (SL) influence is to set the text aside and

translate a few sentenceq aloud, from memory. This will suggest

natural patterns of thought in the first language (L1), which may

not come to mind when the eye is fixed on the SL text.

e. Style and clarity. The translator should not change the style of

the original. But if the text is sloppily written, or full of tedious

repetitions, the translator may, for the reader's sake, correct the

defects.

f. Idiom. Idiomatic expressions are notoriously untranslatable.

These include similes, metaphors, proverbs and sayings (as good

as gold), jargon, slang, and colloquialisms (user-friendly, the Big

Apple, yuppie, etc.), and (in English) phrasal verbs. If the

expressions cannot be directly translated, try any ofthe

following:

- retain the original word, in inverted commas: 'yuppie'

- retain the original expression, with a literal explanation in

brackets: Indian stunrner (dry, hazy weather in late autumn)

- use a close equivalent: talk of the deoil : ouk na rotirna

(literally, 'the wolf at the door')

- use a non-idiomatic or plain prose translation: a bit ooer the top

: un peu excessif.

The golden rule is: if the idiom does not work in the Ll, do not

force it into the translation.

(The principles outlined above are adapted from Frederick Fuller:

The Translator's Handbook. Fot more detailed comments, see Peter

Newmark: Approaches to Translation.)

You might also like

- Game Rules PDFDocument12 pagesGame Rules PDFEric WaddellNo ratings yet

- Connected Speech FeaturesDocument45 pagesConnected Speech FeaturesTayyab Ijaz100% (2)

- (Stephen S. Roach) America's Weak Case Against China - Project SyndicateDocument4 pages(Stephen S. Roach) America's Weak Case Against China - Project SyndicateWenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- Part 1: Aspects of PronunciationDocument8 pagesPart 1: Aspects of PronunciationLilya GilyazevaNo ratings yet

- Notes On English 306A First Examination - February 8, 2000Document9 pagesNotes On English 306A First Examination - February 8, 2000Lhea Pangilinan EstoleNo ratings yet

- Equivalence Above Word Level: Idioms and Fixed ExpressionsDocument3 pagesEquivalence Above Word Level: Idioms and Fixed Expressionseulalia87100% (1)

- Written Work Style GuideDocument9 pagesWritten Work Style GuideNicoleta NechitaNo ratings yet

- #3011 Luindor PDFDocument38 pages#3011 Luindor PDFcdouglasmartins100% (1)

- 5 Features of Connected SpeechDocument7 pages5 Features of Connected SpeechLovely Deins AguilarNo ratings yet

- DLL - The Firm and Its EnvironmentDocument5 pagesDLL - The Firm and Its Environmentfrances_peña_7100% (2)

- ISO 9001:2015 Explained, Fourth Edition GuideDocument3 pagesISO 9001:2015 Explained, Fourth Edition GuideiresendizNo ratings yet

- Annotated TranslationDocument15 pagesAnnotated TranslationZulkifli100% (1)

- Transcript of Sherlock Holmes - The Rediscovered Railway Mysteries and Other StoriesDocument125 pagesTranscript of Sherlock Holmes - The Rediscovered Railway Mysteries and Other StoriesWenxin Huang80% (10)

- Theory and Technique of TranslationDocument39 pagesTheory and Technique of TranslationSaina_Dyana0% (1)

- Essential Japanese Phrasebook & Dictionary: Speak Japanese with Confidence!From EverandEssential Japanese Phrasebook & Dictionary: Speak Japanese with Confidence!Tuttle StudioRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Chapter IV TranslationDocument7 pagesChapter IV TranslationTitinnurwahdaniah Nia100% (1)

- Casting Procedures and Defects GuideDocument91 pagesCasting Procedures and Defects GuideJitender Reddy0% (1)

- Postgraduate Notes in OrthodonticsDocument257 pagesPostgraduate Notes in OrthodonticsSabrina Nitulescu100% (4)

- Thin Film Deposition TechniquesDocument20 pagesThin Film Deposition TechniquesShayan Ahmad Khattak, BS Physics Student, UoPNo ratings yet

- Translation TechniquesDocument4 pagesTranslation TechniquesMaría Elena López SuárezNo ratings yet

- A Textbook of Translation - Peter Newmark 1964 - SUMMARYDocument22 pagesA Textbook of Translation - Peter Newmark 1964 - SUMMARYNanang Sharifudin50% (6)

- Prelim Module Translation and Editing of Text Lesson 1.Document16 pagesPrelim Module Translation and Editing of Text Lesson 1.Reñer Aquino BystanderNo ratings yet

- ChallengesDocument5 pagesChallengesMERVE İREM ALTUNTAŞNo ratings yet

- dịch đại cươngDocument12 pagesdịch đại cươngAnh KimNo ratings yet

- Translating slang and idioms in TV and filmDocument17 pagesTranslating slang and idioms in TV and filmRocio MendigurenNo ratings yet

- 28-Trần Thị Hải YếnDocument4 pages28-Trần Thị Hải YếnHải YếnNo ratings yet

- Translation TechniquesDocument6 pagesTranslation TechniquesEdwin BarbosaNo ratings yet

- Kinds of TranslationDocument6 pagesKinds of Translationsyblaze2000100% (1)

- Tugas Bahasa Inggris 2Document39 pagesTugas Bahasa Inggris 2Riska IndahNo ratings yet

- TPT 14Document2 pagesTPT 14Fajar MalikNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Translation Textbook2020Document27 pagesIntroduction To Translation Textbook2020Taef AljohaniNo ratings yet

- Introducing Corpus Linguistics Fillers (Discourse Markers & Co.) and BackchannelsDocument60 pagesIntroducing Corpus Linguistics Fillers (Discourse Markers & Co.) and Backchannelssara99_loveNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Translation 1Document22 pagesChapter 1 Translation 1Bilal KhlaifatNo ratings yet

- A. Types of Translation MethodDocument5 pagesA. Types of Translation MethodYuliaNo ratings yet

- Translation CampusDocument15 pagesTranslation CampusnonaNo ratings yet

- Definisi Translation Eng-IndoDocument35 pagesDefinisi Translation Eng-IndoarifinznNo ratings yet

- Translation Techniques ExplainedDocument5 pagesTranslation Techniques ExplainedBunga IndahNo ratings yet

- Varieties of Translation and Levels of LiteralismDocument14 pagesVarieties of Translation and Levels of LiteralismNaeem AkramNo ratings yet

- AbstractDocument4 pagesAbstractElitepondyNo ratings yet

- Meaning of LanguageDocument17 pagesMeaning of LanguageLance Arkin AjeroNo ratings yet

- Unit 3Document16 pagesUnit 3Nguyễn HóaNo ratings yet

- Pronunciation Guide: Ugba-100, David RobinsonDocument6 pagesPronunciation Guide: Ugba-100, David RobinsonisvigangadharNo ratings yet

- Translation Prsentation 3Document62 pagesTranslation Prsentation 3Melissa LissaNo ratings yet

- Ii Notion of TranslationDocument7 pagesIi Notion of Translationnanguiyann13No ratings yet

- Basic English Language SkillsDocument95 pagesBasic English Language SkillsLiqaa FlayyihNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Assessment of Grammar HandoutDocument50 pagesTeaching and Assessment of Grammar HandoutHanifa PaloNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - Translation MethodsDocument13 pagesChapter 5 - Translation Methodsayelengiselbochatay@hotmail.comNo ratings yet

- Stylistic Aspect of TranslationDocument8 pagesStylistic Aspect of TranslationVenhrenovych MaiiaNo ratings yet

- Eng. 4104 + 4112 1. Untranslatability: IdiomDocument3 pagesEng. 4104 + 4112 1. Untranslatability: IdiomElla CelineNo ratings yet

- Scientific & Technical Translation Course Sheet 22Document61 pagesScientific & Technical Translation Course Sheet 22b161309No ratings yet

- Translate Personal and Bussiness LetterDocument47 pagesTranslate Personal and Bussiness LetterDiyah Fitri WulandariNo ratings yet

- Subtitling - Basic Principles: Translate EverythingDocument17 pagesSubtitling - Basic Principles: Translate EverythingAnonymous yjZLqQNo ratings yet

- Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University: Faculty of HumanitiesDocument6 pagesIvane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University: Faculty of HumanitiesMariam SinghiNo ratings yet

- Ethics and Professionalism in TranslationDocument25 pagesEthics and Professionalism in TranslationEmanuel VasconcelosNo ratings yet

- Translation and Editing GuideDocument80 pagesTranslation and Editing GuideApenton MimiNo ratings yet

- AdverbDocument5 pagesAdverbRavi InderNo ratings yet

- HANDOUT - VTG Mars-Avril 2022 P20 TraductionDocument48 pagesHANDOUT - VTG Mars-Avril 2022 P20 Traductioncarlostougouma10No ratings yet

- 4.2. Pronunciation and Teaching Techniques 4.2.1. Pronunciation: Vowels, Consonants and SyllablesDocument7 pages4.2. Pronunciation and Teaching Techniques 4.2.1. Pronunciation: Vowels, Consonants and SyllablesMeanmachine SlabbertNo ratings yet

- TUGAS Translation 1 - (Sayid Mahindra)Document3 pagesTUGAS Translation 1 - (Sayid Mahindra)Sayid MahindraNo ratings yet

- Brown and Beige Aesthetic Modern Group Project Presentation 20240305 140501 0000Document9 pagesBrown and Beige Aesthetic Modern Group Project Presentation 20240305 140501 0000Jayron GordonNo ratings yet

- Hoàng Thị Ngọc Hà 2Document5 pagesHoàng Thị Ngọc Hà 2Nguyen Ngoc Thu TrangNo ratings yet

- Dealing With Listening ProblemsDocument3 pagesDealing With Listening ProblemsRICO BUITRAGO LARISSA TATIANANo ratings yet

- Transposition and Modulation + Other TechniquesDocument12 pagesTransposition and Modulation + Other TechniquesAngel David VillabonaNo ratings yet

- Reading For Uae OverviewDocument8 pagesReading For Uae Overviewapi-236417442No ratings yet

- Lost in Translation: Brief Overview of Translation Methods, Human vs Machine Translators, and Translation ChallengesDocument14 pagesLost in Translation: Brief Overview of Translation Methods, Human vs Machine Translators, and Translation ChallengesLeviana DeviNo ratings yet

- Language Part of English Teacher ModuleDocument25 pagesLanguage Part of English Teacher ModuleElena AbadNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Dealing WithDocument13 pagesA Guide To Dealing WithJijoNo ratings yet

- Topic: Principles of Translation Submitted By: Samortin, Lyka Mae S, Moldez, Jam Mari O. ED-41 Submitted To: Mr. Rodolfo MartinezDocument5 pagesTopic: Principles of Translation Submitted By: Samortin, Lyka Mae S, Moldez, Jam Mari O. ED-41 Submitted To: Mr. Rodolfo MartinezJam Mari MoldezNo ratings yet

- Context-Bound WordsDocument32 pagesContext-Bound WordsDina AuliaNo ratings yet

- A bookshelf containing many English translations of the BibleDocument17 pagesA bookshelf containing many English translations of the BibleWenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- Sherlock GuideDocument82 pagesSherlock GuideWenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- English Versions of The BibleDocument2 pagesEnglish Versions of The BibleWenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- Appraising Glances Evaluating Martin S Model of APPRAISALDocument19 pagesAppraising Glances Evaluating Martin S Model of APPRAISALWenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- Formal and Informal LanguageDocument2 pagesFormal and Informal LanguageWenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- Humanitarian Action (Basic Facts)Document11 pagesHumanitarian Action (Basic Facts)Wenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- (M R Pinheiro) Translation Techniques (2015)Document25 pages(M R Pinheiro) Translation Techniques (2015)Wenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- (Jacqueline Noga & Gregor Wolbring) Rio+20 DA Using An Ability Expectation LensDocument25 pages(Jacqueline Noga & Gregor Wolbring) Rio+20 DA Using An Ability Expectation LensWenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- Economic and Social Development (Basic Facts)Document70 pagesEconomic and Social Development (Basic Facts)Wenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- Human Rights (Basic Facts)Document23 pagesHuman Rights (Basic Facts)Wenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- International Law (Basic Facts)Document14 pagesInternational Law (Basic Facts)Wenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- Teaching TranslationDocument4 pagesTeaching TranslationWenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- Versions and Editions of Crabb's SynonymsDocument1 pageVersions and Editions of Crabb's SynonymsWenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- The Interpretive Theory of Translation - WikipediaDocument3 pagesThe Interpretive Theory of Translation - WikipediaWenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- (Chris Guichot de Fortis) Launching A Career in Conference Interpretation (Rev. 10)Document52 pages(Chris Guichot de Fortis) Launching A Career in Conference Interpretation (Rev. 10)Wenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- 2010 National Competitive Recruitment Examination (P-2) : United Nations Nations UniesDocument23 pages2010 National Competitive Recruitment Examination (P-2) : United Nations Nations UniesWenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- 2010 eDocument23 pages2010 eSankar Vaidyanathan100% (1)

- Ncre Sample Exam 2008 PDFDocument19 pagesNcre Sample Exam 2008 PDFWenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- JIU Review of NCRE 2007 9 EnglishDocument38 pagesJIU Review of NCRE 2007 9 EnglishWenxin HuangNo ratings yet

- If V2 would/wouldn't V1Document2 pagesIf V2 would/wouldn't V1Honey ThinNo ratings yet

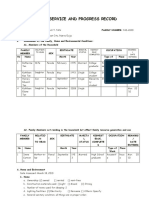

- Family Service and Progress Record: Daughter SeptemberDocument29 pagesFamily Service and Progress Record: Daughter SeptemberKathleen Kae Carmona TanNo ratings yet

- Hyper-Threading Technology Architecture and Microarchitecture - SummaryDocument4 pagesHyper-Threading Technology Architecture and Microarchitecture - SummaryMuhammad UsmanNo ratings yet

- Last Clean ExceptionDocument24 pagesLast Clean Exceptionbeom choiNo ratings yet

- Inorganica Chimica Acta: Research PaperDocument14 pagesInorganica Chimica Acta: Research PaperRuan ReisNo ratings yet

- Break Even AnalysisDocument4 pagesBreak Even Analysiscyper zoonNo ratings yet

- Web Api PDFDocument164 pagesWeb Api PDFnazishNo ratings yet

- Site Visit Risk Assessment FormDocument3 pagesSite Visit Risk Assessment FormAmanuelGirmaNo ratings yet

- Evaluating MYP Rubrics in WORDDocument11 pagesEvaluating MYP Rubrics in WORDJoseph VEGANo ratings yet

- Agricultural Engineering Comprehensive Board Exam Reviewer: Agricultural Processing, Structures, and Allied SubjectsDocument84 pagesAgricultural Engineering Comprehensive Board Exam Reviewer: Agricultural Processing, Structures, and Allied SubjectsRachel vNo ratings yet

- Marshal HMA Mixture Design ExampleDocument2 pagesMarshal HMA Mixture Design ExampleTewodros TadesseNo ratings yet

- Music 7: Music of Lowlands of LuzonDocument14 pagesMusic 7: Music of Lowlands of LuzonGhia Cressida HernandezNo ratings yet

- Good Ethics Is Good BusinessDocument9 pagesGood Ethics Is Good BusinesssumeetpatnaikNo ratings yet

- Free Radical TheoryDocument2 pagesFree Radical TheoryMIA ALVAREZNo ratings yet

- Chem 102 Week 5Document65 pagesChem 102 Week 5CAILA CACHERONo ratings yet

- Lifespan Development Canadian 6th Edition Boyd Test BankDocument57 pagesLifespan Development Canadian 6th Edition Boyd Test Bankshamekascoles2528zNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 124 9636 PDFDocument11 pages10 1 1 124 9636 PDFBrian FreemanNo ratings yet

- Clark DietrichDocument110 pagesClark Dietrichikirby77No ratings yet

- FSRH Ukmec Summary September 2019Document11 pagesFSRH Ukmec Summary September 2019Kiran JayaprakashNo ratings yet

- Antenna VisualizationDocument4 pagesAntenna Visualizationashok_patil_1No ratings yet

- Final Thesis Report YacobDocument114 pagesFinal Thesis Report YacobAddis GetahunNo ratings yet

- Phys101 CS Mid Sem 16 - 17Document1 pagePhys101 CS Mid Sem 16 - 17Nicole EchezonaNo ratings yet

- Main Research PaperDocument11 pagesMain Research PaperBharat DedhiaNo ratings yet