Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Goal Management Training in Adults With ADHD An Intervention Study

Uploaded by

alilaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Goal Management Training in Adults With ADHD An Intervention Study

Uploaded by

alilaCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal ofhttp://jad.sagepub.

com/

Attention Disorders

Goal Management Training in Adults With ADHD: An Intervention Study

Dymphie M. J. M. In de Braek, Jeanette B. Dijkstra, Rudolf W. Ponds and Jelle Jolles

Journal of Attention Disorders published online 20 December 2012

DOI: 10.1177/1087054712468052

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://jad.sagepub.com/content/early/2012/12/20/1087054712468052.citation

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Journal of Attention Disorders can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://jad.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://jad.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> OnlineFirst Version of Record - Dec 20, 2012

What is This?

Downloaded from jad.sagepub.com at Maastricht University on March 10, 2013

468052

urnal of Attention DisordersIn de Braek et al.

2012 SAGE Publications

Reprints and permission:

JADXXX10.1177/1087054712468052Jo

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Articles

Journal of Attention Disorders

Goal Management Training in Adults

XX(X) 18

2012 SAGE Publications

Reprints and permission:

With ADHD: An Intervention Study sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1087054712468052

http://jad.sagepub.com

Dymphie M. J. M. In de Braek1, Jeanette B. Dijkstra1,

Rudolf W. Ponds1, and Jelle Jolles2

Abstract

Objective: This article describes a controlled, neuropsychological intervention study in adult ADHD. We examined

whether adults with ADHD would benefit from a structured course based on Goal Management Training (GMT). The

comprehensive course also included psycho-education on the important aspects of executive functioning as well as

counseling with respect to coping behaviors. Method: The intervention group was compared with a control group

of patients who received psycho-education only (n 12 and n 15, respectively). The effects of the intervention were

evaluated using subjective and objective test measures. In addition, a structured preassessment, an evaluation, and a group

comparison were carried out by an experienced clinician, who was blinded to the intervention itself. Results: The results

of the structured clinical interview obtained in the active intervention group were significantly better in the intervention

group than those of the control group. Conclusion: The findings suggest that the combination of GMT with psycho-

education and counseling may have validity for adults with ADHD. (J. of Att. Dis. 2012; XX(X) 1-XX)

Keywords

ADHD, adults, cognitive training, executive functioning

Introduction Our enquiry was whether patients with ADHD would

benefit from a structured course involving several aspects

In treatment studies in adult ADHD, a major focus has been of executive functioning including psycho-education. Our

pharmacological interventions (Adler, 2008; Kooij et al., hypothesis was that patients who were taught an executive

2004; Lerner & Wigal, 2008; Stein, 2008). Unfortunately, strategy would be able to cope better with cognitive failures

research of psychological treatments is virtually absent. and would display fewer cognitive complaints compared

There is only some preliminary evidence supporting the with a control group of patients who received psycho-

combination of cognitive behavioral therapy and medica- education only. van Hooren et al. (2007) investigated the

tion (Davidson, 2008; Virta et al., 2008). In addition, not all effect of a 6-week structured course on the executive func-

patients respond to pharmacotherapy and they often ask for tioning of older adults in a controlled study (van Hooren

counseling or additional training. In clinical settings, inter- et al., 2007). Their findings indicated that a combination of

ventions regarding planning and organization, or coaching psycho-education and training had the potential to change

are often requested. Although there is abundant neuropsy- the attitude of patients toward their functioning.

chological knowledge of ADHD, this is not used on a regu- The aim of the present study was to investigate the effi-

lar basis in current treatment programs. There are several cacy of cognitive strategy training in adults with ADHD.

neuropsychological models that consider ADHD as a pri- Because executive functioning skills are often compro-

mary deficit in inhibitory control, which is an aspect of mised in adults with ADHD (Barkley, Edwards, Laneri,

executive dysfunction. Barkley (1997) also suggested that Fletcher, & Metevia, 2001; Boonstra, Oosterlaan, Sergeant, &

ADHD is primarily a deficit in inhibitory processes involv- Buitelaar, 2005; Marchetta, Hurks, Krabbendam, & Jolles,

ing executive function (Barkley, 1997). He relates this

inhibitory deficit to prefrontal lobe functioning, possibly 1

Maastricht University Medical Center, Netherlands

2

related to a delay in brain development as other authors also Maastricht University, Netherlands

suggest (Shaw et al., 2007). It is a challenging opportunity

Corresponding Author:

to examine whether adults with ADHD benefit from an Dymphie M. J. M. In de Braek, University Hospital Maastricht,

intervention directed at executive functions, notably the Psychology and Psychiatry, Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, Netherlands

organization and planning of activities in daily life. Email: d.indebraek@maastrichtuniversity.nl

Downloaded from jad.sagepub.com at Maastricht University on March 10, 2013

2 Journal of Attention Disorders XX(X)

2008), we developed an intervention based on the Goal cognitive complaints, expectations of the program, and

Management Training (GMT) for use in adults with ADHD prior treatments. Demographic variables, medication, and

(Levine, 2000). GMT involves different aspects of goal man- complaints of cognitive functioning were obtained. After

agement, which include defining problems, encoding, screening, participants were randomly assigned to the inter-

retrieval strategies, and self-monitoring. Because adults with vention group (GMT ) or the psycho-education-only group

ADHD often suffer from mood swings and low self-esteem, (psycho-education). The follow-up assessments were car-

we added psycho-education to GMT to provide the patient ried out after 12 weeks (T2) and again after 24 weeks (T3).

with more insight into their condition. The aim of psycho- As stated before, the current study was completed in a

education was to give the patients an additional tool to control controlled manner using two active interventions.

their behavior and enable the selection of the most efficient

coping strategy. The psycho-education was concerned with

various aspects of ADHD and various neurocognitive func- Participants

tions, like attention, memory, planning, distraction, and cop- Participants were referred for treatment of cognitive prob-

ing strategies, in particular. These issues were presented in a lems from the outpatient facility for adults with ADHD at

fixed order in every session. The intervention evaluated in the Mondriaan Maastricht, the Netherlands. All participants

present article consisted of 11 group sessions (1 session per had a diagnosis of ADHD (this diagnosis was made by a

week) and 1 individual session per participant. physician experienced in ADHD) and were 18 years of age

The intervention was performed in an evidence-based or older. Major comorbid disorders according to the

fashion. A randomized waiting-list control group design was Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

used and we examined whether this intervention was effec- (DSM-IV-TR; both Axis 1 and Axis 2; American Psychiatric

tive in reducing complaints and in improving cognitive func- Association [APA], 2000) were excluded from the treat-

tioning. During the course, the emphasis was on complaints ment program. The use of psycho-stimulants was not an

experienced by the participants. We therefore expected that exclusion criterion (because of ethical considerations). In

this new neuropsychological treatment program would have our sample, 89% of the participants used psycho-stimu-

an effect on general functioning and on cognitive complaints lants. Three participants did not use psycho-stimulants (two

in particular rather than on actual cognitive performance. The participants in the experimental group and one participant

study was carried out in a controlled manner using two active in the control group). Every participant was screened by a

interventions. There were two complementary methods used certified psychologist on his or her motivation before the

to assess the effects of the intervention studied. First, a neuro- start of the training. None of the participants had partici-

psychological test battery as well as questionnaires were pated previously in a neuropsychological treatment/

used, which are known for their sensitivity in this type of research program. All participants gave informed consent.

intervention study (Valentijn et al., 2005; van Hooren et al., They were randomly assigned to the GMT and psycho-

2007). Second, a completely new approach was taken to eval- education group (GMT group) or the psycho-education-

uate the effect of the neuropsychological intervention. This only group. In total, four groups (two GMT groups and

involved a procedure that has proved its merits in evidence- two psycho-education-only groups) were evaluated.

based pharmacotherapeutic trials in psychiatric or neuropsy- Two participants of the experimental group dropped out;

chiatric patients (Martinez-Martin, Rodriguez-Blazquez, one because of health issues (severe migraine) and the other

Forjaz, & de Pedro, 2009; Quinn et al., 2002; Schneider et al., participant because of comorbid depressive disorder. In the

1997). In short, an experienced clinician blinded to the actual second assessment, two participants were unable to partici-

intervention, which each individual received, assessed the pate; one because of house renovation/work and the other

patient on various aspects of psychological and neuropsycho- participant did not show up at several appointments. One

logical functioning. This clinician used a standardized clini- participant was unable to take part in the clinical interview

cal rating scale to evaluate change in cognitive and global at T3 (because of annual leave) and one participant was

functioning in the participants with adult ADHD. The clinical unable to fill in the Symptom Check List90 (SCL-90) and

rating scale used here was based on the Clinicians Interview- Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ), because of other

Based Impression of Severity and Change (CIBIS and responsibilities (work).

CIBIC), which was originally used in, and is a familiar ele- See Table 1 for information on the participants.

ment of, pharmacological studies (Schneider et al., 1997). Participants in the two groups did not differ according to

age, sex, and level of education. Twelve participants

were included in the experimental group; the control

Method group comprised 15 participants. At baseline there were

Procedure group differences on the clinical rating subscales (cogni-

tion and general). The control group displayed less inter-

A baseline assessment (T1) and two follow-up assessments ference in daily activities through subjective cognitive

(T2, T3) were used. All participants were screened for complaints.

Downloaded from jad.sagepub.com at Maastricht University on March 10, 2013

In de Braek et al. 3

Table 1. Patient Characteristics Table 2. Overview of Structure of the Goal Management

Training (GMT) and Psycho-Education Program

Experimental Control p value

GMT Psycho-education

n 12 15

Age 35.5 37.9 .57 Session 1 Getting acquainted/ Getting acquainted/

Sex (m/f) (7/5) (10/5) .48 information about information about

Education 5.75 5.13 .42 training training

M (SD) Session 2 Identifying high-risk What is ADHD?

SCL-90 160.0 (48.1) 186.9 (67.9) .26 situations

CFQ 67.6 (12.5) 66.5 (18.2) .87 Session 3 Identifying high-risk Attention

Zoo Map (BADS) 98.3 (82.1) 82.9 (68.4) .60 situations/choosing a

CIBIS/C cognition 4.1 (0.9) 3.3 (1.0) .05* personal catchphrase

CIBIS/C general 3.9 (0.8) 3.3 (0.7) .03* Session 4 Use of stop strategy/ Automatic versus

relaxation technique nonautomatic tasks

Note: SCL-90 Symptom Check List90; CFQ Cognitive Failures Session 5 Stop! Memory functioning

Questionnaire; BADS Behavioral Assessment of the Dysexecutive Session 6 Individual session: own Individual sessions: own

Syndrome; CIBIS/C Clinicians Interview-Based Impression of Severity/ goals goals

Change. Independent t tests were used for age and education. Sex was

analyzed using chi-square test. Session 7 State! Decision making Prioritizing

Session 8 State! Decision making Planning

Session 9 Make subtasks (splits) Making a week plan/

terms for an adequate

However, the SCL-90 score was high for both the exper- planning

imental and the control group compared with Dutch norm Session 10 Check and monitor Doing one thing

groups. Also, the CFQ total score was high in both groups at once/adapting

compared with Dutch norm groups, as expected. structure

Session 11 Check and monitor Work/relationships/

finances

Treatment Program Session 12 Overview strategy Overview psycho-

GMT plus psycho-education for ADHD patients. The aim of education

GMT is to teach patients a strategy to improve planning

activities and to structure intentions. The training manual

was previously translated into Dutch for use by older adults Hooren et al., 2007). In the group sessions, the participants

(Levine et al., 2000; Levine, 2000; van Hooren et al., 2007). discussed their cognitive problems with peers and had the

van Hooren et al. (2007) have shown previously that a com- opportunity to support each other. At the end of each ses-

bination of psycho-education and training had the potential sion, participants received homework exercises as well as

to change the attitude of older patients toward their func- hand-outs containing a summary of the session. All topics

tioning (van Hooren et al., 2007). One major addition to were illustrated with practical examples or exercises. The

GMT for ADHD patients concerns the nature of psycho- goal of the first session was to get acquainted with the train-

education, that is, an explanation of the various cognitive ers and other participants as well as with the goals of the

functions and the clinical picture of ADHD in adults in gen- program. The expectations of the program and increasing

eral. Furthermore, specific examples of cognitive failures in insight into the complaints about executive functioning

ADHD were discussed in the group. These examples were were discussed. Psycho-education on ADHD in adults was

based on examples from GMT used by van Hooren et al. examined and participants were asked to reflect on what

(van Hooren et al., 2007). Because of the addition of psy- ADHD meant to them. In the second, third, and fourth ses-

cho-education, the program was adapted to consist of 12 sions, high-risk situations were identified, the stop strategy

sessions, 1 individual session and 11 group sessions. The was introduced using an automatic pilot metaphor, and a

content of each session and the order in which the topics personal catchphrase was chosen, for instance, time-out,

were addressed were structured in a protocol (see Table 2). ho!, or wait a minute. In the fifth session psycho-educa-

The group session was coordinated by two clinical neuro- tion with respect to memory functioning was offered. The

psychologists: a trainer and an assistant. At the start of the stop strategy was extended in Sessions 4 and 5 by means of

program, each group comprised a minimum of 6 and a max- a relaxation technique; information processing and working

imum of 8 persons to ensure that the training group could memory were also discussed (see Table 2). In the sixth ses-

function optimally. There were 2-hr sessions for 12 con- sion, expectations of the course, (individual) personal prob-

secutive weeks. A manual containing the full text and tasks lems, and goals were talked about. Sessions 7 and 8 focused

used by the trainer was available. The trainer included on setting a goal. In Sessions 7 and 8, psycho-education on

examples put forward by the participants in the session. All prioritizing and planning was discussed. Session 9 was used

sessions were structured (see also for an elaboration; van to discuss splitting a complex task into subtasks and then to

Downloaded from jad.sagepub.com at Maastricht University on March 10, 2013

4 Journal of Attention Disorders XX(X)

Table 3. Structure of Goal Management Training (GMT) and indicative of a larger number of symptoms. The SCL-90

Psycho-Education Program total score was used as a measure of distress.

Group conversation (how was your week?) 15 min

Discussion of homework 15 min Objective Executive Functioning

GMT 30 min Zoo Map From the Behavioral Assessment of the Dysexecu-

Break 15 min tive Syndrome (BADS). The Zoo Map subtest is a planning

Psycho-education 30 min test. It provides information about the ability to plan a route

Round off and explanation homework 15 min to visit 6 of a possible 12 locations in a zoo. The out-

come measure chosen was the time needed to plan a route

(unstructured version), because GMT involves teaching

prioritize these subtasks. In this session, psycho-education participants to stop their ongoing behavior and take more

on planning and organization was presented. The main time to plan (Burgess, Alderman, Evans, Emslie, & Wilson,

theme of Sessions 10 and 11 was to check current behavior, 1998; Krabbendam, de Vugt, Derix, & Jolles, 1999).

for instance, to check whether the goals set were still ade-

quate. Psycho-education for this session was doing one

thing at the time. In the final session, an overview was Clinical Rating Scale

given and participants received an assignment in which A certified and experienced clinical neuropsychologist who

they had to use the strategies learned and translate those to was not involved in the treatment program and blind to the

their daily lives. This assignment was then discussed in the condition or group (GMT or psycho-education only) inter-

group (Table 3). viewed the participants. He rated participants at baseline

Psycho-education only. For the control group psycho-edu- and at the two follow-up meetings (after intervention) with

cation only, the psycho-education in every session did not respect to six areas of functioning. This included cognition,

contain the strategy training. In the control group, conversa- everyday functioning, work/social functioning, mood, and

tion was allowed and homework was discussed. The psy- general functioning according to the CIBIS and CIBIC

cho-education was structured and presented in exactly the (Schneider et al., 1997)). Prior to the clinical rating, the

same order and in a similar manner as to the GMT group. neuropsychologist explained to the participants that he was

Therefore, the sessions of the psycho-education group blind to their condition and would not discuss themes

(from T1 until T2) lasted 1.5 hr, instead of the 2 hr for the from the program. At baseline, participants were rated on a

GMT plus psycho-education group. In the final session 7-point scale: 1 no cognitive disorders, 2 subjective

(Session 12), an overview of the psycho-education was complaints, no interference in daily life, 3 subjective com-

given. After the psycho-education program had finished, plaints and moderate interference in daily life, 4 subjec-

the participants of the control group were given the strategy tive complaints and severe interference in daily life, 5 mild

training. disorders, 6 moderate disorders, and 7 severe disorders.

At the two follow-up assessments, participants were

again rated on a 7-point scale: 1 very much improved, 2

Outcome Measures much improved, 3 minimally improved, 4 no change, 5

Subjective Functioning minimal worsening, 6 moderate worsening, and 7 severe

CFQ. CFQ was used to evaluate the frequency of every- worsening. The aspects most interesting in this study were

day cognitive failures, including subjective executive func- the ratings of everyday functioning in general and cognition

tioning. The scale is validated in Dutch and consists of 25 in particular as GMT was developed to teach patients a

items measuring the frequency of everyday cognitive fail- strategy for improving planning activities and to structure

ures in the domains of memory, attention, perception, and intentions and therefore diminish cognitive complaints.

action (Broadbent, Cooper, FitzGerald, & Parkes, 1982;

Ponds, Commissaris, & Jolles, 1997). Participants were

asked to indicate on a 5-point scale how often they experi- Other Measures

enced particular cognitive failures (very often, quite often, Age was used as a continuous variable. Level of education

occasionally, very rarely, never). Answers were recoded was indexed on an 8-point ordinal scale, ranging from pri-

following Dutch instructions (Ponds et al., 1997). A higher mary to university education (De Bie, 1987).

score on the CFQ indicates a larger number of cognitive

failures.

SCL-90. This is a multidimensional, self-reporting inven- Statistical Analyses

tory of psychopathology (Derogatis, Rickels, & Rock, Although the participants were randomly assigned to the

1976). The scores for the Anxiety, Depression, and Sleep two groups, possible differences could exist between these

subscales ranged from 0 to 50, 0 to 80, and 0 to 15, respec- by chance. We first examined whether there were important

tively. On all three scales, a higher score is considered demographic differences between the experimental and

Downloaded from jad.sagepub.com at Maastricht University on March 10, 2013

In de Braek et al. 5

control groups. Using independent t tests, we compared age Table 4. Means, Standard Deviation, Difference Scores (T2 T1)

and level of education between the two groups. We also and p Values of the Independent t Tests

compared the level of distress (as measured by the SCL-

FU1 FU2 FU2 FU1 p value

90), cognitive failures, planning time, and CIBIS at base-

line between the two groups (see Table 1). A chi-square test CFQ

was used to analyze group differences with respect to sex. Exp 50.7 (13.6) 48.9 (10.1) 8.8 (8.7) .439

General Linear Model (GLM) with repeated-measures Control 51.3 (16.7) 45.3 (15.3) 5.7 (9.4)

ANOVA was applied to examine the effect of intervention. SCL-90

Analyses were carried out with group (two levels: experi- Exp 152.3 (50.3) 130.8 (23.9) 15.0 (40.8) .983

mental and control group) as between-subject factor and time Control 167.5 (55.7) 151.9 (38.5) 14.6 (42.6)

Zoo Map

(three levels: baseline, first follow-up, and second follow-up)

Exp 62.3 (48.6) 71.1 (73.6) 45.5 (84.9) .781

as the within-subject factor. Second, as we were primarily

Control 52.1 (41.7) 39.9 (35.4) 35.6 (83.7)

interested in differences between the two groups at T2, dif-

CIBIC

ference scores were calculated for all outcome measures

Cognition

(T2 T1), except for the ratings on the clinical rating scale Exp 2.5 (0.5) .024*

(as change was already measured in the clinical rating). To Control 3.1 (0.8)

examine the effects of intervention on cognitive complaints General

as well as planning time at Assessment 2 (T2) and 3 (T3), Exp 2.7 (0.7) .438

independent t tests were carried out in both groups. Control 2.9 (0.8)

The 15th version of the Statistical Package for the Social

Note: FU1 Follow-Up 1; FU2 Follow-Up 2; CFQ Cognitive

Sciences (SPSS) for Windows was used for the statistical anal- Failures Questionnaire total score; Exp experimental; SCL-90

yses (SPSS Inc., Chicago), with p .05 as significance level. Symptom Checklist90 total score; Zoo Map planning time in seconds

(Behavioral Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome [BADS]); CIBIC

Clinicians Interview-Based Impression of Change.

Results

Effects of GMT Plus Psycho-

Education for ADHD Patients 70

GMT+

psycho-education

In the second assessment, a significant effect was found 60

between the two groups on the clinical rating scale for the

domain cognition, F(1, 22) 0.656, p .024 (Table 4). 50

The clinician rated the participants in the experimental

CFQ-score

40

group as cognitively more improved between baseline (T1)

and first follow-up (T2). The two groups did not differ on 30

the clinical rating scale for the domain general function-

20

ing, F(1, 22) 0.028, p .438. Second, GLM showed an

effect of time for SCL-90 total score, CFQ total score, and 10

zoo planning time, F(1, 21) 11.86, p .002), F(1, 20)

35.66, p .000, F(1, 22) 6.99, p .015. There were no 0

1 2 3

interaction effects between group and time on any of the

Time

measures (Figures 1, 2, and 3).

No significant effect was found with respect to the dif-

ference scores between Follow-Up 1 (T2) and Follow-Up Figure 1. CFQ total score for the GMT group and psycho-

2 (T3) on level of distress as measured by the SCL-90, education-only group at baseline (1), follow-up after 12 weeks

F(1, 21) 0.000, p .983. Also, no significant effect was (2), and follow-up after 24 weeks (3)

Note: CFQ Cognitive Failures Questionnaire; GMT goal

found with respect to the difference scores between management training and psycho-education group.

Follow-Up 1 (T2) and Follow-Up 2 (T3) on cognitive

failures, F(1, 21) 0.064, p .434. Finally, no significant

differences were found with respect to the planning time domain cognition at first follow-up as rated by the

(Zoo Map subtest from the BADS) at Follow-Up 1 (T2), experienced clinician (p .04; Table 5).

F(1, 22) 0.882, p .781. Post hoc additional nonpara-

metric analyses were done to examine whether the changes

we found were in fact in the right direction (that is GMT- Discussion

associated changes). The Kruskal-Wallis (with the use of The aim of this investigation was to establish whether

a grouping variable) revealed a significant effect for the patients with ADHD would benefit from a structured

Downloaded from jad.sagepub.com at Maastricht University on March 10, 2013

6 Journal of Attention Disorders XX(X)

Table 5. Mean Scores and Standard Deviations Over Time for

the Two Groups (Experimental vs. Control)

200

GMT+ Baseline Measurement 2 Measurement 3

psycho-education

180

Experimental

SCL-90 167.3 (49.4) 152.3 (50.3) 130.8 (23.9)

160

CFQ 67.6 (12.5) 74.3 (13.6) 77.5 (10.8)

SCL-90 total score

Zoo Map 98.3 (82.1) 62.3 (48.6) 64.2 (68.6)

140

CIBIC-C 4.1 (0.9) 2.5 (0.5) 2.5 (0.8)

120

CIBIC-G 3.92 (0.8) 2.7 (0.7) 2.4 (0.7)

Control

100 SCL-90 186.9 (67.9) 167.5 (55.7) 156.8 (48.2)

CFQ 66.5 (18.2) 73.7 (16.7) 79.7 (15.3)

80 Zoo Map 82.9 (68.4) 52.1 (41.7) 40.0 (34.1)

CIBIC-C 3.3 (1.0) 3.1 (0.8) 2.4 (0.6)

60 CIBIC-G 3.3 (0.7) 2.9 (0.7) 2.5 (0.8)

1 2 3

Note: SCL-90 Symptom Checklist90 total score; CFQ Cognitive

Time

Failures Questionnaire total score; Zoo Map planning time in seconds

(Behavioral Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome [BADS]);

CIBIC Clinicians Interview-Based Impression of Change, CIBIC-C

Figure 2. SCL-90 total score for the GMT group and psycho- cognition, CIBIC-G general.

education-only group at baseline (1), follow-up after 12 weeks

(2), and follow-up after 24 weeks (3)

Note: SCL-90 Symptom Check List90; GMT goal management

training and psycho-education group. cognitive failures and would have fewer cognitive com-

plaints compared with patients who received psycho-

education only. The first finding in this study was that

there were no significant differences between the two

4,5 groups (experimental and control) with respect to age,

GMT+

4

psycho-education

level of education, or level of distress. The clinician, how-

3,5 ever, rated that there was more interference in daily life

Clinic rating cognition

3 activities for the experimental group. Both groups scored

2,5 high on measures of distress and frequency of cognitive

2

failures. Although participants with severe comorbidity

were excluded from the intervention, the mean level of

1,5

distress and complaints in several domains like depres-

1

sion, anxiety, and sleep was overall high. There was also

0,5 a great variance between individuals with respect to the

0 level of distress. Although comorbid psychiatric disorders

Assesment 2 Assesment 3

were described as an exclusion criterion, the level of dis-

tress between participants in both groups strongly varied.

Figure 3. Clinical rating with respect to cognition for the For instance, the range of the SCL-90 total score was

GMT group and psycho-education-only group at follow-up between 110 and 289.

after 12 weeks (2), and follow-up after 24 weeks (3) A second finding of the present study was the significant

Note: GMT goal management training and psycho-education group.

Clinical rating: 1 very much improved, 2 much improved, 3 minimally effect of time on subjective and objective test measures

improved, 4 no change, 5 minimal worsening, 6 moderate worsening, in both groups. On the CIBIC, the experimental group

7 severe worsening. improved more in the domain of cognitive functioning. This

was in line with our hypothesis. In the current study, the

CIBIC was used for the first time in a controlled neuropsy-

course based on neuropsychological insights and including chological intervention study. The rating procedure carried

several aspects of executive functioning. A new research out by a health professional blind to the protocol and who

tool was used to evaluate the possible effect of the inter- uses the CIBIC has the potential in detecting changes over

vention in this controlled clinical study. For this purpose, time. The present study proves that this is true not only for

a clinical rating scale, the CIBIC/CIBIS, was used. The pharmacological treatment but also for nonpharmacological

main hypothesis was that patients who were taught an treatment. Interestingly, the present study showed that the

executive strategy would be able to cope better with CIBIC was sensitive to detecting clinical changes, whereas

Downloaded from jad.sagepub.com at Maastricht University on March 10, 2013

In de Braek et al. 7

regular measurements, such as the level of complaints and that because the control group had the advantage of dis-

objective test measures were not. Furthermore, an impor- tributed practice, the control group would in fact improve

tant advantage of the CIBIC is that the clinician is blinded more over time (Wilson, 2003).

to the condition and that the rating is based on a clinical This study found an effect of GMT over and above psy-

interview. cho-education for adults with ADHD in a clinical interview.

As stated before, on other subjective and objective test The CIBIC was sensitive to detect clinical change and has

measures, no group differences were found. Our hypothesis potential in the contribution to the evaluation of neuropsy-

that participants involved in GMT would display less dis- chological intervention. Future research should include

tress and fewer cognitive complaints could only partly be larger groups and a waiting-list control group.

confirmed (by using the CIBIC). Our research was aimed at

investigating whether GMT would have an additional effect Declaration of Conflicting Interests

on psycho-education. The present study has not found very The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with

strong evidence for this. One explanation is that, in hind- respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this

sight, our control group was given a full intervention (active article.

control), which included peer interaction and providing

information, which could have a positive treatment effect Funding

on increasing awareness of cognitive problems in itself. The author(s) received no financial support for the research,

Therefore, our control group was not in all respects an authorship, and/or publication of this article.

actual control group, but was in fact another active treat-

ment program. The fact that peers interacted with each other References

about their complaints and discussed factors like personal- Adler, L. A. (2008). Neurobiology, pharmacology, and emerging

ity, coping styles, and cognitive problems seems to have treatment. CNS Spectrum, 13, 9(Suppl. 13), 4.

had an effect on the results. A limitation of this study was American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statisti-

that the control group did not receive the same duration of cal manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington,

treatment sessions as the GMT group. In fact, the control DC: Author.

group received more group sessions. It would have been Barkley, R. A. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention,

welcome if both groups received an equal amount of group and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of

sessions. However, it is encouraging that the GMT group ADHD. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 65-94.

seems to improve more than the control group though less Barkley, R. A., Edwards, G., Laneri, M., Fletcher, K., &

group sessions are involved. Another factor that needs to be Metevia, L. (2001). Executive functioning, temporal dis-

considered is the fact that the group of participants was very counting, and sense of time in adolescents with attention

heterogeneous. The diagnosis of ADHD is based on the deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional

DSM-IV-TR criteria for children (APA, 2000). The main defiant disorder (ODD). Journal of Abnormal Child Psy-

symptoms are inattentiveness, hyperactivity, and impulsiv- chology, 29, 541-556.

ity. Participants in this study were heterogeneous with Boonstra, A. M., Oosterlaan, J., Sergeant, J. A., & Buitelaar, J. K.

respect to ADHD symptoms. Qualitative information (2005). Executive functioning in adult ADHD: A meta-analytic

showed that some participants improved a lot after the GMT review. Psychological Medicine, 35, 1097-1108.

program whereas other participants did not benefit from the Broadbent, D. E., Cooper, P. F., FitzGerald, P., & Parkes, K. R.

training. Future research should be aimed at gaining insight (1982). The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its

into what type of participants are sensitive to GMT and correlates. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 21, 1-16.

what factors contribute to this. Burgess, P. W., Alderman, N., Evans, J., Emslie, H., & Wilson, B. A.

Qualitative information showed that the experimental (1998). The ecological validity of tests of executive function.

group improved 12 weeks after the intervention program Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 4,

stopped (T3). This is very promising information as it could 547-558.

be possible that the effects of the strategy training need time Davidson, M. A. (2008). ADHD in adults: A review of the litera-

to become a new automatic process. Because of ethical ture. Journal of Attention Disorders, 11, 628-641.

reasons, the control group received the strategy training De Bie, S. E. (1987). Standaardvragen 1987: Voorstellen voor uni-

between T2 and T3. Therefore, we were unable to measure formering van vraagstellingen naar achtergrondkenmerken en

actual long-term effects of GMT in adults with ADHD. interviews [Standard questions 1987: Proposal for uniformisa-

Future research could include investigating GMT in adults tion of questions regarding background variables] (2nd ed.).

with ADHD compared with a waiting-list control group. In Leiden, Netherlands: Leiden University Press.

this study, it was ethically not allowed to make the con- Derogatis, L. R., Rickels, K., & Rock, A. F. (1976). The SCL-90

trol group wait because of the high level of distress it could and the MMPI: A step in the validation of a new self-report

cause and need of care of participants. It could be assumed scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 128, 280-289.

Downloaded from jad.sagepub.com at Maastricht University on March 10, 2013

8 Journal of Attention Disorders XX(X)

Kooij, J. J., Burger, H., Boonstra, A. M., Van der Linden, P. D., hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical

Kalma, L. E., & Buitelaar, J. K. (2004). Efficacy and safety of maturation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

methylphenidate in 45 adults with attention-deficit/hyperac- of the United States of America, 104, 19649-19654.

tivity disorder. A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind Stein, M. A. (2008). Treating adult ADHD with stimulants. CNS

cross-over trial. Psychological Medicine, 34, 973-982. Spectrum, 13(Suppl. 13), 8-11.

Krabbendam, L., de Vugt, M. E., Derix, M. M., & Jolles, J. (1999). Valentijn, S. A., van Hooren, S. A., Bosma, H., Touw, D. M.,

The behavioral assessment of the dysexecutive syndrome as a Jolles, J., van Boxtel, M. P., & Ponds, R. W. (2005). The effect

tool to assess executive functions in schizophrenia. Clinical of two types of memory training on subjective and objective

Neuropsychologist, 13, 370-375. memory performance in healthy individuals aged 55 years and

Lerner, M., & Wigal, T. (2008). Long-term safety of stimulant older: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and

medications used to treat children with ADHD. Journal of Counseling, 57, 106-114.

Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 46, 38-48. van Hooren, S. A., Valentijn, S. A., Bosma, H., Ponds, R. W.,

Levine, B., Robertson, I. H., Clare, L. R., Carter, G., Hong, J., van Boxtel, M. P., Levine, B., & Jolles, J. (2007). Effect of a

Wilson, B. A., & Stuss, D. T. (2000). Rehabilitation of execu- structured course involving goal management training in older

tive functioning: An experimental-clinical validation of goal adults: A randomised controlled trial. Patient Education and

management training. Journal of International Neuropsycho- Counseling, 65, 205-213.

logical Society, 6, 299-312. Virta, M., Vedenpaa, A., Gronroos, N., Chydenius, E., Partinen,

Marchetta, N. D., Hurks, P. P., Krabbendam, L., & Jolles, J. (2008). M., Vataja, R., & Iivanainen, M. (2008). Adults with ADHD

Interference control, working memory, concept shifting, and benefit from cognitive-behaviorally oriented group rehabilita-

verbal fluency in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity dis- tion: A study of 29 participants. Journal of Attention Disor-

order (ADHD). Neuropsychology, 22, 74-84. ders, 12, 218-226.

Martinez-Martin, P., Rodriguez-Blazquez, C., Forjaz, M. J., & Wilson, B. A. (2003). Neuropsychological Rehabilitation: Theory

de Pedro, J. (2009). The clinical impression of severity index and practice. Cambridge, UK: Swets and Zeitlinger, BV.

for Parkinsons disease: International validation study. Move-

ment Disorders, 24, 211-217. Bios

Ponds, R. W., Commissaris, K. J., & Jolles, J. (1997). Prevalence Dymphie M. J. M. In de Braek has a PhD in psychology (ADHD

and covariates of subjective forgetfulness in a normal popu- in adults) and works as a health psychologist/neuropsychologist at

lation in The Netherlands. International Journal of Aging & the memory clinic of the Maastricht University Medical Center

Human Development, 45, 207-221. (MUMC).

Quinn, J., Moore, M., Benson, D. F., Clark, C. M., Doody, R.,

Jagust, W., & Kaye, J. A. (2002). A videotaped CIBIC for Jeanette B. Dijkstra has a PhD in psychology (specialization

dementia patients: Validity and reliability in a simulated clini- neuropsychology and aging). She is a clinical neuropsychologist

cal trial. Neurology, 58, 433-437. at the MUMC where she works at the memory clinic.

Robertson, I. H. L. (2001). Goal management training. Dublin,

Ireland. Rudolf W. Ponds professor and head of the department of psy-

Schneider, L. S. B., Olin, J. T., Doody, R. S., Clark, C. M., chology and psychiatry at the MUMC. He works as a clinical

Morris, J. C., Reisberg, B., & Ferris, S. H. (1997). Valid- neuropsychologist at the memory clinic and at Adelante rehabili-

ity and reliability of the Alzheimers Disease Cooperative tation center.

Study-Clinical Global Impression of Change. The Alzheimers

Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Jelle Jolles is a full professor in educational neuropsychology at

Disorders, 11(Suppl. 2), S22-S32. VU Amsterdam. Since January 2009 he has been the director of

Shaw, P., Eckstrand, K., Sharp, W., Blumenthal, J., Lerch, J. P., the Research Institute AZIRE, at the Faculty of Psychology &

Greenstein, D., & Rapoport, J. L. (2007). Attention-deficit/ Education in Amsterdam (VU).

Downloaded from jad.sagepub.com at Maastricht University on March 10, 2013

You might also like

- ADHD ORGANIZING SOLUTIONS: Techniques for Efficient Organization That Will Reduce Your Stress (2022 Guide for Beginners)From EverandADHD ORGANIZING SOLUTIONS: Techniques for Efficient Organization That Will Reduce Your Stress (2022 Guide for Beginners)No ratings yet

- ADHD Through The Life CycleDocument34 pagesADHD Through The Life Cyclegamesh waran ganta100% (4)

- Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) Symptom Checklist Adult ADHDDocument4 pagesAdult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) Symptom Checklist Adult ADHDapi-12695071100% (11)

- Coaching For Adhd Brain Surfing EbookDocument37 pagesCoaching For Adhd Brain Surfing Ebookburtu100% (7)

- Manage Your Life - The Daily Routine That Works For Adults With Adhd PDFDocument12 pagesManage Your Life - The Daily Routine That Works For Adults With Adhd PDFletitia2hinton100% (19)

- Coping With ADHDDocument60 pagesCoping With ADHDanon-973128100% (9)

- Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) Symptom Checklist: NameDocument6 pagesAdult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) Symptom Checklist: NameRakesh Kushwaha100% (2)

- Adult ADHD Diagnosis and Treatment GuideDocument19 pagesAdult ADHD Diagnosis and Treatment GuideJavier Cotobal100% (1)

- ADHD Coaching ResourcesDocument2 pagesADHD Coaching Resourceshamid100% (4)

- The Ultimate ADHD Toolkit 1Document15 pagesThe Ultimate ADHD Toolkit 1Kirtana Jayagandan100% (6)

- ADD Living With ADDDocument32 pagesADD Living With ADDAriel Meller100% (5)

- Handbook ADHD StudențiDocument134 pagesHandbook ADHD Studențimihaela neacsu100% (2)

- Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS)Document3 pagesAdult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS)amaandrei100% (1)

- Misdiagnosis: ADHD or Depression?Document24 pagesMisdiagnosis: ADHD or Depression?Judie GadeNo ratings yet

- Adult ADHD Test 18 Question ADHD-ASRS-v1-1 Adhd-Npf - Com Quality ApprovedDocument3 pagesAdult ADHD Test 18 Question ADHD-ASRS-v1-1 Adhd-Npf - Com Quality ApprovedADHD and ADD100% (12)

- ADHD Therapy WorksheetDocument22 pagesADHD Therapy Worksheetmizbigspenda100% (2)

- Adhd Sabotages Your RelationshipDocument1 pageAdhd Sabotages Your Relationshipletitia2hintonNo ratings yet

- Manage Your Life - 73 Adhd Friendly Ways To Organize Your Life Now PDFDocument10 pagesManage Your Life - 73 Adhd Friendly Ways To Organize Your Life Now PDFAnonymous Kv663l100% (8)

- Nonmedication Treatments For ADHD in AdultsDocument168 pagesNonmedication Treatments For ADHD in AdultsMaricela Virgen Enciso100% (5)

- Better Time ManagementDocument11 pagesBetter Time Managementjamesm66100% (5)

- ADHD - BarkleyDocument6 pagesADHD - Barkleycodepalm650100% (6)

- (Treatments That Work) Steven A. Safren, Susan E. Sprich, Carol A. Perlman, Michael W. Otto - Mastering Your Adult ADHD_ A Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment Program, Therapist Guide-OXFORD UNIVERSITY PREDocument185 pages(Treatments That Work) Steven A. Safren, Susan E. Sprich, Carol A. Perlman, Michael W. Otto - Mastering Your Adult ADHD_ A Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment Program, Therapist Guide-OXFORD UNIVERSITY PREBettina Osztertág-Barak100% (24)

- The ADHD ToolkitDocument161 pagesThe ADHD Toolkitrachisan95% (61)

- You Mean I M Not CrazyDocument462 pagesYou Mean I M Not CrazyJmont100% (15)

- 11 ADHD Coping MechanismsDocument7 pages11 ADHD Coping Mechanismsamaandrei100% (9)

- Barkley Adult Adhd Rating ScaleDocument2 pagesBarkley Adult Adhd Rating ScaleCintia Ferris Lantero100% (11)

- ADHD Vitamin SupplementsDocument6 pagesADHD Vitamin SupplementsColeen Navarro-Rasmussen100% (5)

- Barkley Adhd Fact SheetsDocument10 pagesBarkley Adhd Fact Sheetsapi-83101465No ratings yet

- Adhd Time Assessment Chart: From Additude'S ExpertsDocument6 pagesAdhd Time Assessment Chart: From Additude'S ExpertsViviek Persaud100% (1)

- Current Directions in ADHD and Its TreatmentDocument314 pagesCurrent Directions in ADHD and Its TreatmentSofía Lecter100% (1)

- The Ultimate Guide To ADHD MedicationDocument20 pagesThe Ultimate Guide To ADHD MedicationTolga Aydogan86% (7)

- Adhd 101Document111 pagesAdhd 101alipiodepaula100% (11)

- ADHD Library BooklistDocument3 pagesADHD Library BooklistAotearoa Autism100% (2)

- Barkley, 2011Document43 pagesBarkley, 2011ludilozezanje100% (2)

- Adult ADHD - Effective Treatment StrategiesDocument15 pagesAdult ADHD - Effective Treatment StrategiesDefault User100% (4)

- Adhd Add Adult TestDocument1 pageAdhd Add Adult Testlogan50% (2)

- Many Faces of AdhdDocument3 pagesMany Faces of Adhdinetwork2001No ratings yet

- ADHD Screening Test PDFDocument20 pagesADHD Screening Test PDFdcowan94% (17)

- Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1) Symptom Checklist InstructionsDocument6 pagesAdult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1) Symptom Checklist InstructionsUnoduetre Stella100% (1)

- Executive Functions and ADHD in Adults EvidenceDocument13 pagesExecutive Functions and ADHD in Adults Evidencedianisvillarreal100% (1)

- Getting Things Done With Adult ADHDDocument94 pagesGetting Things Done With Adult ADHDschumangel100% (3)

- Adhd TipsDocument22 pagesAdhd TipsVeejhayCShaah80% (5)

- Adhd LecturesDocument32 pagesAdhd Lecturescinfer75100% (4)

- Adult Adhd 101Document42 pagesAdult Adhd 101superm530100% (10)

- Taking Charge of Adult ADHD - Russell A. BarkleyDocument4 pagesTaking Charge of Adult ADHD - Russell A. Barkleynuzopapa13% (16)

- Solanto - CBT For Adult ADHDDocument31 pagesSolanto - CBT For Adult ADHDTamás PetőczNo ratings yet

- Understand Conditions - Secrets of The Adhd BrainDocument16 pagesUnderstand Conditions - Secrets of The Adhd Brainol100% (8)

- ADHD in Adults A Review of The LiteratureDocument15 pagesADHD in Adults A Review of The Literaturemeldovale100% (1)

- Adhd Add BillsDocument2 pagesAdhd Add Billslogan0% (1)

- The Adult ADHD & ADD Solution - Discover How to Restore Attention and Reduce Hyperactivity in Just 14 Days. The Complete Guide for Diagnosed Children and ParentsFrom EverandThe Adult ADHD & ADD Solution - Discover How to Restore Attention and Reduce Hyperactivity in Just 14 Days. The Complete Guide for Diagnosed Children and ParentsNo ratings yet

- May We Have Your Attention Please?: A Springboard Clinic Workbook for Living—and Thriving—with Adult ADHDFrom EverandMay We Have Your Attention Please?: A Springboard Clinic Workbook for Living—and Thriving—with Adult ADHDRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- The ADHD Fix: 15 Strategies You Need to Use to Achieve Your True PotentialFrom EverandThe ADHD Fix: 15 Strategies You Need to Use to Achieve Your True PotentialRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- The Adult ADHD Handbook for Patients, Family & FriendsFrom EverandThe Adult ADHD Handbook for Patients, Family & FriendsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Embracing ADHD: A Transformational JourneyFrom EverandEmbracing ADHD: A Transformational JourneyRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Clinician's Guide to Adult ADHD: Assessment and InterventionFrom EverandClinician's Guide to Adult ADHD: Assessment and InterventionNo ratings yet

- Understand Your Brain, Get More Done: The ADHD Executive Functions WorkbookFrom EverandUnderstand Your Brain, Get More Done: The ADHD Executive Functions WorkbookRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- How Any Adult with ADHD Can Lead a Normal Life: Living and Succeeding As a Hunter in a World Full Of FarmersFrom EverandHow Any Adult with ADHD Can Lead a Normal Life: Living and Succeeding As a Hunter in a World Full Of FarmersRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- ADHD In Adults: Am I ADHD? Interactive Questions For ADHD AssessmentFrom EverandADHD In Adults: Am I ADHD? Interactive Questions For ADHD AssessmentRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (2)

- Adult ADHD Treatment: The Pros And Cons - How To Treat ADHD EffectivelyFrom EverandAdult ADHD Treatment: The Pros And Cons - How To Treat ADHD EffectivelyNo ratings yet

- Existential Counselling & Psychotherapy TechniquesDocument34 pagesExistential Counselling & Psychotherapy TechniquesElisa Travailleur100% (1)

- Ancient views and modern perspectives on abnormal behaviorDocument8 pagesAncient views and modern perspectives on abnormal behaviorLouise Agravio100% (1)

- Scoring YSQDocument2 pagesScoring YSQAnders Xerxes Sonson87% (30)

- Background of The StudyDocument3 pagesBackground of The StudyEben Alameda-PalapuzNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11-15 PsychassDocument7 pagesChapter 11-15 PsychassCLAUDINE DOLINONo ratings yet

- Somaliland Who Aims Report PDFDocument24 pagesSomaliland Who Aims Report PDFOmar AwaleNo ratings yet

- Standards of Psychiatric-Mental Health Nursing PracticeDocument4 pagesStandards of Psychiatric-Mental Health Nursing PracticeAnna Sofia ReyesNo ratings yet

- Eating Disorders Reading Comprehension Exercises 6785Document1 pageEating Disorders Reading Comprehension Exercises 6785Estidwar Serrano100% (2)

- The Role of The Social Worker With Older PersonsDocument15 pagesThe Role of The Social Worker With Older PersonsAaqibNo ratings yet

- Gender DysphoriaDocument5 pagesGender DysphoriaRochelle Cuenca100% (1)

- Chapter 10Document6 pagesChapter 10Bilal QureshiNo ratings yet

- Stress, Sex Differences, and Coping Strategies Among College StudentsDocument13 pagesStress, Sex Differences, and Coping Strategies Among College StudentsSamNo ratings yet

- M-CHAT Scoring Key: Does Your Child Take An Interest in Other Children?Document1 pageM-CHAT Scoring Key: Does Your Child Take An Interest in Other Children?bramafixsNo ratings yet

- HCAMS Hurricane Assistance LetterDocument2 pagesHCAMS Hurricane Assistance LetterCWALocal1022No ratings yet

- Program at a Glance Simposium 3 Days PsychiatryDocument3 pagesProgram at a Glance Simposium 3 Days PsychiatryBayu Bayu AriatamaNo ratings yet

- Ocd Presentation 3Document11 pagesOcd Presentation 3api-387888714No ratings yet

- Educational Assessment Tools and Processes REFSDocument10 pagesEducational Assessment Tools and Processes REFStracycw100% (1)

- The Kick Start V2Document21 pagesThe Kick Start V2Krishna PrasadNo ratings yet

- ZEELIST - Freud, Links, VoodooDocument3 pagesZEELIST - Freud, Links, VoodooJon LouisNo ratings yet

- CLIENT VARIABLES and Psychotherapy OutcomesDocument20 pagesCLIENT VARIABLES and Psychotherapy OutcomespsicandreiaNo ratings yet

- Freud's Psychosexual Stages of DevelopmentDocument8 pagesFreud's Psychosexual Stages of DevelopmentSharanu HolalNo ratings yet

- 6 DepressionDocument42 pages6 DepressionEIorgaNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion and Wellness in Physical TherapyDocument24 pagesHealth Promotion and Wellness in Physical TherapyGio SalvacionNo ratings yet

- Defense Mechanisms ExplainedDocument3 pagesDefense Mechanisms ExplainedQueen Anne Bobier - tomacderNo ratings yet

- Level of knowledge on positive stress coping mechanismsDocument54 pagesLevel of knowledge on positive stress coping mechanismsSolsona Natl HS MaanantengNo ratings yet

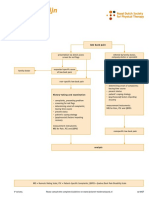

- Dutch LBP Physiotherapy FlowchartDocument2 pagesDutch LBP Physiotherapy FlowchartyohanNo ratings yet

- Guidelines Dementia Age Related Cognitive ChangeDocument32 pagesGuidelines Dementia Age Related Cognitive ChangeFernanda Keren de PaulaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 PsychDocument35 pagesChapter 11 PsychÁro DeemsNo ratings yet

- CPE104 Lesson8Document4 pagesCPE104 Lesson8Jelody Mae GuibanNo ratings yet

- Walking With Dobermanns (Part 1)Document4 pagesWalking With Dobermanns (Part 1)Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeNo ratings yet