Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2015 Shealy ChoiceArchitecture

Uploaded by

anitazhindonOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2015 Shealy ChoiceArchitecture

Uploaded by

anitazhindonCopyright:

Available Formats

Choice Architecture as a Strategy to Encourage

Elegant Infrastructure Outcomes

Tripp Shealy 1 and Leidy Klotz 2

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by VIRGINIA TECH UNIVERSTIY on 05/02/16. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

Abstract: Infrastructure that meets users needs with less complexity can satisfy growing demand and relieve system pressures. Such

outcomes are defined as elegant. Unfortunately, social and cognitive biases can inhibit infrastructure stakeholders from achieving these

outcomes. In other fields, similar biases are overcome with well-designed choice architecture, which considers how the presentation of

choices effects the decisions that are ultimately made. Using a metasynthesis research approach, this article describes cognitive biases that

can inhibit elegant infrastructure and then presents strategies to mitigate these biases with choice architecture interventions. The emphasis

here is on high-impact decisions with cost-effective and plausible choice architecture interventions. This systematic merging of behavioral

science and infrastructure systems is meant to provide readers with the background and examples needed to investigate choice architecture as

a strategy to influence the infrastructure outcomes they desire. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)IS.1943-555X.0000311. 2016 American Society of

Civil Engineers.

Introduction decisions. A request for design proposals for any practice to reduce

overflow of combined sewers will likely yield more options than

Hundreds of billions of dollars are spent every year to build and a request for proposals to install stormwater piping and sewage-

retrofit physical infrastructure systems (OECD 2013). Those man- retention structures to reduce overflow of combined sewers. Both

aging and designing these systems use procedures and processes requests describe the problem, common in cities with aging infra-

such as contract structures (Anastasopoulos et al. 2010), project structure, but the first description is open to more solutions because

management hierarchies (El-Diraby 2013), and operation and there is no prescribed design outcome.

maintenance schematics (Bolar et al. 2014). Infrastructure deci- Choice architecture can be designed to meet desired infrastruc-

sions are also dependent on decision environments (Shealy and ture outcomes. In the BIM example, if energy efficiency is a goal,

Klotz 2015) and are influenced by risk, uncertainty (Son and Rojas materials that insulate well could be listed first. If the goal is to sell

2011), and cognitive biases (Cattell et al. 2011; van Buiten and more of a certain product, that product could be listed first, and so

Hartmann 2013). Choice architecture (CA) is presented as another on (Carney and Banaji 2012). To provide a consistent example, the

strategy to help meet growing infrastructure demands. focus of this article is on how various types of choice architecture

Choice architecture uses insight from behavioral science to can lead to infrastructure outcomes that are elegant, as described in

explain how the presentation of options can impact the decisions the Background section that follows.

that are made. Grouping options together, presenting options before

others, preselecting choices, or framing attributes as positive or

negative all are examples of choice architecture (Thaler et al. Objective

2010). Fields from medicine (Johnson and Goldstein 2003) and

law (Johnson 1993) to finance (Thaler and Benartzi 2004) are using Previous studies suggest cognitive biases and social heuristics dis-

choice architecture to improve decision processes. tort managerial decisions in complex infrastructure governance,

This paper suggests that intentional consideration of how planning, and delivery (Klotz et al. 2010; Klotz 2010; Beamish

choices are presented in infrastructure planning can lead to im- and Biggart 2012; van Buiten and Hartmann 2013). Research at

proved project outcomes. Consider, for example, a building infor- the intersection of behavioral science and technical solutions

mation modeling (BIM) program presenting designers with material may help reduce these biases (Allcott and Mullainathan 2010). This

choices. Materials shown first are more likely to be selected than article is meant to provide readers with the background and exam-

ples needed to investigate choice architecture as a strategy to influ-

those in the middle of the list, especially if the list of materials

ence the infrastructure outcomes they desire.

is long. Lists like these could be organized so that desirable materi-

als appear first (perhaps those that will promote energy efficiency,

if that is a goal). Choice architecture also influences larger-scale Background: Elegance in Infrastructure (and Barriers

to It)

1

Assistant Professor, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering, A biologist sees elegance in a neurons electrical transmitters or

Virginia Tech, 200 Patton Hall, Blacksburg, VA 24061 (corresponding the way a desert mouses kidney efficiently recaptures moisture.

author). E-mail: tshealy@vt.edu A product designer sees elegance in a functional and seductive

2

Associate Professor, Glenn Dept. of Civil Engineering, Clemson Univ.,

iPhone (Apple). A computer scientist sees elegance in code that

208 Lowry Hall, Clemson, SC 29634. E-mail: leidyk@clemson.edu

Note. This manuscript was submitted on January 8, 2015; approved on requires fewer lines to accomplish a task. Elegance has a slightly

February 16, 2016; published online on April 20, 2016. Discussion period different meaning in these and other contexts, but there are unifying

open until September 20, 2016; separate discussions must be submitted similarities.

for individual papers. This paper is part of the Journal of Infrastructure To distill these similarities and apply them to infrastructure,

Systems, ASCE, ISSN 1076-0342. domains that have previously defined and characterized elegant

ASCE 04016023-1 J. Infrastruct. Syst.

J. Infrastruct. Syst., 04016023

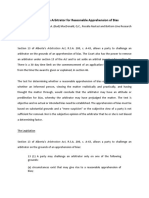

1. Biases and 3. Synthesized 4. Overlay

2. Distillation

heuristics Results Infrastructure

Self Interested bias

Affect heuristic

Saliency bias

Confirmation bias

Check for External

Availability bias Validation Loss Aversion

Uncertainty Comparison

Friction Case Based

Anchoring bias

Sunk Cost Infrastructure

Sunk cost Myopia Examples

Endowment effect Review with JDM Uncertainty

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by VIRGINIA TECH UNIVERSTIY on 05/02/16. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

Myopia Experts

Overconfidence

Loss aversion

Status Quo

Certainty Effect

Satisficing

Comparison Friction

(Compiled from Wilson & Dowlatabadi, 2007; Todd & Houde, 2011; Johnson et al., 2012; van

Buiten & Hartmann, 2013).

Fig. 1. Four-quadrant infrastructure system design

systems are explored. These include (as described in the remainder Related to fixing the root cause, subtraction that adds value is

of this section): manufacturing, product design, architecture, com- present in many elegant solutions (May 2009). Apple Computers

puter science, organizational systems, and biology. The list was simple user interfaces are one example and companies including

synthesized from these domains to core elements and themes. Toyota (Japan), Google (Mountain View, California), Trader Joes

The resulting definition for elegant infrastructure outcomes are (Monrovia, California), and ING Direct (Amsterdam, Netherlands)

those which (1) satisfy stakeholder needs; (2) fix a root problem, all emphasize subtraction in various forms (Siegel and Etzkorn

not a symptom; and (3) subtract rather than add to create value. 2013). An infrastructure example of subtraction that adds value

Most infrastructure projects meet some degree of stakeholder is when reduced artificial lighting leads to improved productivity.

needs, but elegant solutions do so efficiently and to a higher degree Because office workers spend the majority of their time looking at

of functionality. For example, a home designed with a mechanical air backlit computer screens, reducing lighting decreases the glare,

conditioning system likely meets user needs for space and comfort at which in turn decreases headaches (Loftness 2013). Subtraction that

a competitive cost. However, a passive house design, with features adds value is also found in the example of the shared space concept

like superior insulation, south facing windows, and extended over- in city transportation design. By removing traffic lights, street signs,

hangs, may be able to satisfy these same needs more elegantly by roadway markings, and curbs, drivers feel uncertain about right-of-

reducing operation costs without increasing production costs. ways and reduce speeds to accommodate pedestrians (Vanderbilt

In public infrastructure, such as a water treatment plant, there 2008). Cities including West Palm Beach, Florida; Drachten,

are more stakeholders (e.g., water consumers, contractors, plant Germany; and London report fewer accidents and more-efficient

employees, neighbors, and public interest groups). Elegant solu- traffic flow after implementing this subtractive design approach

tions require consideration of each of these stakeholders needs (McNichol 2004; Shore 2010; Moody and Melia 2013).

(Smith 2010; Madni 2012). For the water treatment example, this

could mean the plant must provide clean water, be easy to maintain Barriers That Can Discourage Elegance

and cost less to construct, all while relieving pressures on outdated Unintentional incentives for complexity in contract structures can

systems (Billows 1999). Satisfying all users needs is not easy, prevent elegance in infrastructure projects. Some military contracts,

which is one reason why elegant outcomes are uncommon. for example, do not allow engineering design costs to exceed 6%

Elegant outcomes do not just meet stakeholder needs, they also of total construction costs (Niece 2005). Design firms subject to

go beyond symptoms to fix root causes (Madni 2012). Looking this well-intentioned rule face a perverse incentive: identifying a

deep to the root cause requires persistence, as presented in Fig. 1. less-expensive, elegant construction solution could lead to a re-

Systems that are overcapacity and fail to meet user needs are duced fee for their firm. Similarly, fixed fee contracts pay designers

characterized in Quadrant I. These systems may add complexity to review drawings and technical specifications on an hourly basis.

over time by only addressing symptoms of underlying problems. When designs are complex, the designer can more easily justify

Solutions, represented in Quadrant III may correct complexity of their hours spent (Brydges 2016). Elegant designs, on the other

Quadrant I, but over simplification can also lead to not meeting hand, may appear intuitive or simple, making it more difficult for

user needs. Adding appropriate complexity can lead to user needs the designer to illustrate just how much time was spent to overcome

being met, but elegant outcomes result in Quadrant IV, where user complexity and arrive at elegance.

needs are met with less complexity (May 2009; Madni 2012; Siegel Social norms can also impede elegance, in particular the desire

and Etzkorn 2013). In other words, elegant solutions relieve pres- to see something tangible for investments, including those in infra-

sures on complex systems (infrastructure) to provide additional structure improvements (The Economist 2007; Wald 2007). Home-

stakeholder benefits. owners attempting to reduce energy use are more likely to buy a

ASCE 04016023-2 J. Infrastruct. Syst.

J. Infrastruct. Syst., 04016023

new refrigerator that they will see every day than add hidden attic User needs are not met User needs are met

insulation, even though the insulation is typically more cost effec- Quadrant I Quadrant II

tive and saves more energy (Gardner and Stern 2008). Similarly, Highly Inefficient Complexity:

funds allocated for building-code enforcement are sometimes redi- Complex Redundant Complexity:

Inadequate performance;

rected toward other activities more visible to taxpayers (Eisenberg Satisficing; Opportunities

Solutions System layers not

and Persram 2009). exist for more simplicity.

addressing root problem.

Other social norms that may impede elegance are those celebrat-

ing conspicuous consumption (OCass and McEwen 2004). Quadrant III Quadrant IV

Preference for new infrastructure could result from similar norms

that lead to preference for the newest model television. Compared Simple Elegant: break through

with infrastructure projects that have subtracted towards invisible Solutions Simple: Under designed

complexity; Not

elegance, complex and visible projects lend themselves to ribbon and not utilized.

redundant; Optimal.

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by VIRGINIA TECH UNIVERSTIY on 05/02/16. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

cutting ceremonies, magazine feature articles, and donor naming

rights. Visible improvements celebrate tangible progress and

completion of a complex task, which is part of the social norm Fig. 2. Metasynthesis to combine cognitive biases and infrastructure

(Elster 1989). cases

Biological characteristics of the brain may also make subtractive

elegant outcomes less likely. Compared with addition, subtraction

takes longer for the brain to process and produces lower degrees of et al. 2012) also informed the framework for applying JDM to

accuracy (Gonzalez et al. 2005; Payne et al. 1993; Yi-Rong et al. infrastructure decisions.

2011). Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scans This framework is similar in structure to previous hierarchical

that measure blood flow of activated neurons may offer one explan- frameworks that include a review of sustainable building practices

ation. These scans show that subtraction activates more neurons (Abdellatif and Al-Shammaa 2015) and relating economic lab

than addition, and therefore requires more energy (Yi-Rong et al. experiments to real-world examples (Camerer 2004). The review

2011). of literature produced a list of biases and case-based infrastructure

examples comprised from JDM literature review. A compare and

Cognitive Biases as Barriers contrast method with JDM experts synthesized these biases to those

In addition to the incentives, social norms, and biological character- that hold the greatest potential barriers to elegant infrastructure out-

istics of the brain, other possible barriers to subtractive elegance in

comes. Two experts were chosen based on their contribution to

infrastructure include cognitive biases. This is when decision mak-

JDM research. Each expert has more than 20,000 citations within

ers deviate from predicted outcomes and make seemingly irrational

the field of JDM. The synthesis was done through an initial review

choices that are not in their best interest (e.g., Ariely 2008; Hilbert

by each expert separately and a second review of the distilled find-

2012). Specific cognitive biases that may be inhibiting elegant in-

ings in consultation with experts together. The initial findings were

frastructure are identified using a metasynthesis approach and de-

compared and contrasted when reviewers agreed and disagreed.

scribed in the Results and Analysis section along with proposed

The final list incorporated these revisions and joint revisions into

approaches to counter these biases. Cognitive biases are of particu-

the synthesized results. Fig. 2 provides the cognitive biases exam-

lar interest because behavioral and decision sciences offer oppor-

ined and the synthesized list using the compare and contrast

tunities to reduce them with minimal effort or cost in comparison to

method with JDM experts. For readers interested in the larger list

the effort and cost associated with changing government regula-

of possible biases and heuristics (Step 1) that did not make the syn-

tions, incentives, and social norms.

thesized list (Wilson and Dowlatabadi 2007; Todd and Houde

2011; Johnson et al. 2012; van Buiten and Hartmann 2013).

Method: Metasynthesis Approach The example cognitive biases that follow in this article all exhibit

A metasynthesis literature review approach is appropriate when external validity, meaning results from multiple studies in many

researchers seek to integrate findings from multiple research stud- domains suggest similar conclusions. For example, one of the biases

ies, often from several fields of study (Ogawa and Malen 1991). presented is loss aversion. The original study by Kahneman

In literature about sustainable infrastructure, a similar conceptual and Tversky (1984) has been replicated and modified in studies

approach to merging research domains has led to a new unified of decisions about candy bars (Knetsch 1989), hunting permits

definition of sustainability and resilience (Bocchini et al. 2014) (Cummings et al. 1986), and college basketball tickets (Carmon

and insight about infrastructure as a chaotic sociotechnical system and Ariely 2000). Further studies about international conflict (Levy

(El-Diraby 2013). A metasynthesis approach is used to investigate 1996), labor supply (Goette et al. 2004), and domestic military

and illustrate how understanding cognitive biases and applying intervention (Nincic 1997) reveal implications of loss aversion in

choice architecture could assist efforts to achieve elegant infrastruc- complex decision scenarios. Loss aversion is now generally ac-

ture outcomes. cepted as both a description and explanation of the phenomenon

Starting with seminal overviews of prospect theory (Kahneman (Novemsky and Kahneman 2005).

and Tversky 1979), bounded rationality (Kahneman 2003), and The cognitive biases and associated choice architecture exam-

decision-making under risk and uncertainty (Hardman 2009), a ples in the following section are meant to illustrate the vast potential

framework was developed for applying judgment and decision- for research in this area and point researchers to some opportunities

making (JDM) concepts to infrastructure decisions. The sources that seem to have potential for high impact. The examples are not

for the seminal overview were chosen because of their broad exhaustive; there are many cognitive bias/elegant infrastructure

reach (e.g., Hardman 2009) and early development of theory combinations to study related to infrastructure design and decision

(e.g., Kahneman and Tversky 1979). Applications of JDM in res- making. The recommendations of the judgment and decision-

idential energy (Wilson and Dowlatabadi 2007), energy policy making experts are combined, and this article presents five high-

(Todd and Houde 2011), infrastructure publicprivate partner- impact biases and associated choice architecture examples: loss

ships (van Buiten and Hartmann 2013), and marketing (Johnson aversion, comparison friction, sunk cost, myopia, and uncertainty.

ASCE 04016023-3 J. Infrastruct. Syst.

J. Infrastruct. Syst., 04016023

Table 1. Select Cognitive Biases

Cognitive bias Definition Relevant literature

Loss aversion To avoid loss; loss provokes greater degrees of discomfort Benartzi and Thaler (1995), Kahneman and

than a win provides satisfaction Tversky (1984), and McGraw et al. (2010)

Comparison The lack of available comparative information Ellison and Ellison (2009), Hastings and Weinstein (2008), and

friction to make a decision Kling et al. (2012)

Sunk costs Costs that cannot be recovered, often money already spent, Arkes and Blumer (1985) and Thaler (1980)

influences current or future decisions

Myopia Evaluation of options based on immediate gain Shamosh and Gray (2008), Shiv et al. (2005), and Weber (2006)

rather than long term gains

Uncertainty Probability of outcomes are unknown Fox and Tversky (1998) and Kahneman and Tversky (1992)

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by VIRGINIA TECH UNIVERSTIY on 05/02/16. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

Results and Analysis: Selected Cognitive Biases not in a format that decision-makers can use, decision-making

InhibitingAnd Choice Architecture Approaches to can suffer. An example from the auto industry shows the potential

EncourageInfrastructure Elegance benefits from reducing this comparison friction. Until recently, fuel

economy labels on new vehicles displayed city and highway mile-

Based on the metasynthesis literature review, the examples that fol- age per gallon. Now, similar labels display projected annual fuel

low illustrate how cognitive biases can inhibit elegant infrastructure cost over 5 years as well as a comparison to the fuel cost of the

and how choice architecture can be used to overcome them. As part average vehicle. These labels provide more information to the con-

of the conceptual merging of these domains, the cognitive biases sumer in a format that makes sense, therefore improving their abil-

that appeared to have a choice architecture approach with potential ity to pick the most beneficial option (Larrick and Soll 2008).

to influence infrastructure decisions and practicality for interven- An analogous example from infrastructure could be the use

tion are prioritized. In other words, choice architecture that is likely of intelligent transportation systems (ITS) to provide information

to have a big impact and be able to overcome these biases are pre- to reduce comparison friction. Data collected from smartphones

sented. Table 1 is a list of biases and definitions based on the meta- and global positioning systems (GPS) can allow engineers to

synthesis literate review. see traffic patterns in real time, which helps inform their decision-

making (Walker et al. 2014). Appropriate solutions can then be

Loss Aversion identified, including other ITS applications such as adaptable

speed-limit signs and traffic-light sequences as well as smartphone

Kahneman and Tverskys (1984) concept of loss aversion shows applications to alert drivers of delays ahead. ITS technologies like

that people generally prefer not losing something to winning the these can provide information to reduce comparison friction for

exact same thing. In other words, loss provokes greater degrees those making decisions during infrastructure planning.

of discomfort than a win provides satisfaction. At 50=50 odds, the

risk to overcoming an initial loss often requires the potential win to

be roughly twice as great (Benartzi and Thaler 1995). Decision- Sunk Costs

makers are not always uniformly risk averse. When decision-makers People become emotionally invested in money already spent and

are already losing, for example, they are more likely to become risk continue to pay regardless of current costs, benefits, or losses

seeking (Kahneman and Tversky 1992). Loss aversion helps explain (Arkes and Blumer 1985). This sunk cost thinking can lead to con-

why home sellers overprice a house in a down market (Genesove and tinually trying to recoup the initial investment (Thaler 1980).

Mayer 2001) or when investors hold a losing stock too long (Odean A familiar example is continuing to watch a bad movie simply be-

1998). This effect is measureable in the brain. Financial gains gen- cause the ticket is already paid for (Arkes and Blumer 1985).

erate activity in the analytic section of the brain whereas losses Costs already sunk into complex infrastructure can be a barrier

generate processing between the emotional and analytic sections to choosing elegant future solutions. The preliminary design for

(Martino et al. 2006). Because of the different locations of this the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) highway cost Oregon and

neuron activity, losses are associated with an emotional pain in a Washington taxpayers $140 million. When citizens pleaded for a

way that gains are not (Rick 2011; Sokol-Hessner et al. 2012). more elegant multimodal design, government officials cited this

This same psychological obstacle may have been a contributing (relatively) small sunk design cost as a reason for the $3.5 billion

factor to delayed redevelopment of the Embarcadero Freeway in construction project to proceed without the multimodal consider-

San Francisco. Loss-averse city officials and groups advocating ations (Manvel 2011).

for removal of the freeway were unable to make progress until

an earthquake caused structural failure, making removal a necessity

Myopia

(Eckerson 2006). With the freeway removed, property values

jumped threefold as redevelopment plans were enacted, including Myopia is characterized by a desire for immediate gratification and

newly constructed tree-lined boulevards, a pedestrian promenade, can lead to decision-making that does not give sufficient weight

bicycles paths, and a neighborhood streetcar (Norquist 2000). In to future outcomes (Shiv et al. 2005). In experiments where sub-

this case, it took an earthquake to free the decision-making process jects were given a choice between receiving $100 immediately

from loss-averse stakeholders, which led to a more elegant infra- or $120 in one month, the majority chose the immediate $100

structure and street design. (Buonomano 2012), even though there are very few investments

that would return 20% in one month.

Shifting short-term decisions to longer-term ones can reduce

Comparison Friction

myopic influences. For example, in experiments where subjects

Decisions are often made by comparing differences between op- were given a choice between receiving $100 in 12 months or

tions. However, when information is not available, or when it is $120 in 13 months, the majority chose to wait the extra month

ASCE 04016023-4 J. Infrastruct. Syst.

J. Infrastruct. Syst., 04016023

for the $120 (Buonomano 2012). The reason for the shift in pref- Choice Architecture: Overcoming the Barriers to

erence ($100$120) is because immediate gratification ($100 now) Subtraction

was no longer an option. When both outcomes required a waiting

period, subjects decision-making shifted to view the increase Choice architecture is an approach well-suited to overcoming

in money as more gratifying. Field studies show similar results. the cognitive barriers to subtraction and elegant outcomes. Choice

Employees are more likely to commit to, and follow through architecture demonstrates that the way information is presented in-

with, retirement savings if it is through upcoming bonuses and fluences the decisions made (Thaler and Sunstein 2008). Just as

salary increases rather than current take-home earnings (Thaler and there is no neutral building design, there is no neutral choice de-

Benartzi 2004). sign. Building materials, location, size, and color influence how

Applied to infrastructure, myopia may be a contributing influ- people interact with a buildings space. Similarly, the orders of op-

ence in decisions to reduce construction costs at the expense of tions, preselected choices, or even added detail can all influence

future operation and maintenance costs (Chalifoux 2006). In res- decisions made. How a choice is presented affects the reasoning

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by VIRGINIA TECH UNIVERSTIY on 05/02/16. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

idential construction, for example, the upfront costs of more envi- process even when two methods of posing a decision are formally

ronmentally friendly homes are cited as a purchasing barrier (Green equivalent, because each may give rise to different psychological

Homeowner 2016). Thermal insulating windows and polyurethane processes including the influential cognitive biases mentioned in

wall insulation are more efficient than single-pane windows and the previous section. This rationale is supported by query theory,

fiberglass batts, but the added efficiency brings additional upfront in which choices are made based on a linear series of questions and

cost. These premium products produce substantial payback over the these questions are dependent on the starting point (Johnson et al.

lifetime of the home, yet the upfront cost and delayed payback is a 2007). Initial questions produce longer, richer responses than later

myopic barrier homeowners often cannot overcome (Cabeza et al. questions and, subsequently, this impacts the outcome (Weber et al.

2010). Like delaying the $120 decision a year, offsetting initial 2007). Groups without predecided reasoning and goals are ob-

costs or delaying costs over time could help reduce myopia in served to use a similar decision-making method (Milch et al. 2009).

these instances. Bills such as property assessed clean energy Those constructing decisions for infrastructure planning can use

(PACE) attempt to create more immediate paybacks and delay up- choice architecture to remove barriers to, or even promote, the sub-

front costs by providing loans that are attached to the property, tractive qualities that can lead to more elegant outcomes. In Fig. 1,

rather than homeowner. Owners benefit from the savings immedi- choice architecture can help move infrastructure decisions from

ately and pay the PACE loan back over an annual term (typically Quadrants IIII to Quadrant IV. For example, Autodesks Ecotect

1520 years). BIM tool provides designers with construction and material op-

tions. Rearranging the program inventory to show energy-efficient

products first or in a way that reduces the number of clicks to select

Uncertainty

them might lead to more designers selecting these options. Ecotect

When decisions involve risk but lack a numerical probability, could reduce the psychological barrier of comparison friction by

decision-makers tend to assign their own probability based on their incorporating renewable energy sources such as photovoltaic pan-

experience. The problem is that having prior experience leads to els, wind turbines, and geothermal wells into the energy modeling

underestimation of risk, while having no prior experience leads software (Cho et al. 2010). Designers could more easily compare

to overestimation (Heath and Tversky 1991). The amount of detail the cost versus benefit of including these features into a project.

the decision-maker has about each choice can influence their Selected choice architecture concepts are listed in Table 2

perception of probability. All else being equal, the more informa- and described in subsequent subsections in terms of the following

tion, the more confident the decision-maker becomes about the concepts: risk framing, attribute framing, partitioning options, set-

outcome, regardless of the relevance of the information (Fox and ting high goals, feedback, and defaults [choice architecture tools

Tversky 1998). abound and not all of them are discussed here. Interested readers

Uncertainty could be a contributing factor to reluctance in the can start with Choice architecture (Thaler et al. 2010); Beyond

construction industry to depart from industry standards and norms nudges: Tools of a choice architecture (Johnson et al. 2012); and

(Beamish and Biggart 2010). Stakeholder groups, such as building Nudging and choice architecture: Ethical considerations (Sunstein

code officials, are less likely to approve systems they have no pre- 2015)]. For each concept, a real-world case is provided to illustrate

vious experience inspecting (Eisenberg and Persram 2009). This its relevance to infrastructure decision making to encourage sub-

reluctance can become a problem when it inhibits adoption of unfa- tractive elegant outcomes. The list of choice architecture applica-

miliar but elegant infrastructure approaches, such as decentralized tions is not comprehensive, but rather a framework for departure,

wastewater systems, which remove needless piping by treating with examples and opportunities. The list was developed using a

wastewater closer to the source. similar approach as the list of cognitive biases: two leading experts

Table 2. Choice Architecture Interventions to Overcome Cognitive Biases

Cognitive bias Barrier to elegant solution Possible CA intervention

Loss aversion People do not like to lose; elegance requires subtraction Risk framing (Kahneman and Tversky 1984); attribute framing

(Marteau 1989)

Comparison Choices are limited; elegance requires looking Setting goals rather than choices (Heath et al. 1999); feedback

friction past these limitations loops (Van Houwelingen and Raaij 1989)

Sunk costs Previous investments influence current choice; Risk framing (Kahneman and Tversky 1984); attribute framing

elegance may require abandoning these investments (Marteau 1989)

Myopia Prefer now over future; elegance requires thinking Partitioning options (Levav et al. 2010); attribute framing

about future costs and value

Uncertainty Reluctance to depart from industry norm; elegance requires Defaults (Madrian and Shea 2001); attribute framing

moving past industry norm

ASCE 04016023-5 J. Infrastruct. Syst.

J. Infrastruct. Syst., 04016023

in the field of JDM and choice architecture provided content and allows car buyers to make one decision rather than many. Each

face validity by reviewing and editing the findings separately and choice within a given partition receives the same amount of time

then reviewing the synthesized conclusions together. and weight (Levav et al. 2010). Isolating a choice causes the op-

posite effect. Decision-makers perceive nonpartitioned options as

Risk Framing equally important in decision weight to the entire group of deci-

sions within a partition (Martin and Norton 2009).

Risk framing is a way to describe outcomes of choices that have An example of isolating choices as applied to selection of

varying levels of risk in different ways. Kahneman and Tversky transportation options is the Summer Streets program, which limits

(1984) demonstrated that people made decisions in a health context city streets to pedestrians and bicyclists for one day a month

differently whether the risk was framed in terms of losses or gains. (Khawarzad 2011). By isolating transportation options, even for a

Two groups were asked to select a treatment option for a disease short period of time, the program can lead to an elegant shift where

outbreak expected to kill 600 people. Group one was asked if they people choose to bike or walk after the Summer Streets program

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by VIRGINIA TECH UNIVERSTIY on 05/02/16. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

would rather save 200 lives or provide a one-third probability to ends. Indeed, a similar event in Bogota, Colombia attracts 1.8 million

save all 600 lives and two-third probability that no lives are saved. people every week. Popularity of the event lead city officials to

Group two was asked if they would rather let 400 people die or shift transportation funding from road infrastructure to building

provide one-third probability that nobody will die and two-third 300 km of pedestrian and bicycle only lanes (Press 2011).

probability that all 600 people will die. When outcomes were

framed positively, as lives saved, participants were more likely

Setting High, Achievable Goals

to choose the certain choicesaving 200 people. Conversely,

the negatively framed outcome (lives lost) prompted the risky op- Goal setting provides intrinsic motivation for achievement. Once a

tiontrying to save all 600 people. The change in frame from gain goal is reached, that motivation to achieve more decreases (Heath

to loss reversed participant preferences. Subsequent research shows et al. 1999). Reaching a goal provides a similar satisfaction as over-

experts are just as susceptible as laypeople to framing effects coming loss aversion. Excelling past a goal is a similar feeling to

(Duchon et al. 1989; Marteau 1989). winninga great feeling but not the same as not losing. Setting

Risk framing could be applied to the previously described San higher goals can extend motivation to achieve the highest-level

Francisco Embarcadero Freeway example. Perhaps city officials outcomes.

would have been more likely to support the project before the earth- Policy makers and industry groups establish infrastructure

quake if their decision was framed in terms of losses, i.e., by not sustainability goals through certifications and rating systems such

demolishing the bridge and not adding a mix-use boulevard, the as EnergyStar, leadership in energy and environmental design

city could lose $50 million in economic development. If the city (LEED), and envision. Setting goals in these systems too low can

council and public viewed demolishing the bridge as the risky decrease the motivation to achieve higher scores and, more pos-

choice, presenting the loss option likely provides a better chance sibly, elegant outcomes (Jacowitz and Kahneman 1995; Strack et al.

for this choice to be selected. 1988; Klotz et al. 2010). Raising sustainability goals to higher

levels would prompt greater motivation and likely lead to a high

score, even if the goal were never met.

Attribute Framing

Highlighting one attribute over another evokes different feelings and Feedback

thus influences decisions. Those with different political affiliations

changed preferences when a carbon dioxide surcharge was labeled Decision-makers are more accountable about performance when

a tax or offset (Hardisty et al. 2010). Patients told a surgery is 90% they receive feedback about their decisions (Kluger and DeNisi

successful are more likely to opt for surgery than when told the same 1996). More knowledge allows for more-frequent improvements.

surgery fails 10% (Marteau 1989). People pay more for a burger when Equipping homes with display screens showing real-time energy

described as 75% lean than 25% fat (Levin and Gaeth 1988). Attribute consumption can lead to significant reductions in energy consump-

framing is not the same as risk framing because only one attribute tion (Dobson and Griffin 1992). The frequency of feedback impacts

within the context is the subject of manipulation (Levin et al. 1998). savings. Those who receive continuous feedback saved more en-

Highlighting attributes of elegant infrastructure could have sim- ergy than those receiving monthly feedback (van Houwelingen

ilar results. The former mayor of Bogota, Colombia, Enrique Penal- and van Raaij 1989).

osa, used attribute framing to gain support for building a bus rapid Evidence-based construction management for healthcare facili-

transit (BRT) system instead of expanding the city highways. When ties evaluates current research, best practices, and past performance

talking with other city officials, Penalosa frequently cited the 80% to inform current decisions and predictions (Becker and Parsons

of citizens relying on public transportation as a reason to support 2007). The evidence-based construction term draws from evi-

BRT over highways. Penalosa credits this statistic as being a critical dence-based medicine, in which doctors track patient performance

decision-making influence (Eckerson 2007). to inform future treatment options. In construction, a series of

feedback loops function as indicators for future methods and design

options. Relating evidence-based construction methods to other

Partitioning of Options forms of infrastructure development could increase knowledge

gathering and adoption of new techniques. An owner could man-

Providing too many choices can have negative impacts, in the form date feedback in the contract asking designers and contractors to

of choice overload, where users become indecisive, unhappy and perform occupant evaluations or collect user feedback before the

even refrain from making a decision (Iyengar and Lepper 2000). project is completely turned over.

Partitioning decisions, both in groups and over time, is one way

of structuring decision processes to deal with a long list of options

Defaults

more efficiently and effectively. Rather than asking a car buyer nu-

merous decisions about each feature, the car manufacturer acts as Setting a default condition imposes a decision even when an indi-

the choice architect by grouping decisions into packages. This vidual does not make one. European countries using opt-out

ASCE 04016023-6 J. Infrastruct. Syst.

J. Infrastruct. Syst., 04016023

defaults for organ donations report 10 times the participation rates With further study, specific choice architecture interventions

as countries with opt-in defaults. Thus, for organ donation, setting hold promise as relatively simple and cost-effective approaches

the correct default can save lives (Johnson and Goldstein 2003). to achieving desired infrastructure outcomes. Do myopic tenden-

The reason why defaults are so powerful is not as obvious as cies and sunk-cost fallacies contribute to the undervaluing of long-

other choice architecture examples. Defaults influence three differ- term investments in infrastructure? Are loss aversion, uncertainty,

ent user conditions: effort, endorsement, and reference dependence and comparison friction inhibiting more widespread implementa-

(Dinner et al. 2010). Employees who do not select a 401(k) retire- tion of uncommon types of projects, like road diets? Behavioral

ment plan in the United States, displaying a lack of effort to make a science literature suggests that this is likely the case, which means

decision, still save money because of a predetermined 3% annual choice architecture can help.

investment default (Madrian and Shea 2001). Endorsement means Literature on decision optimization in construction processes

decision-makers may perceive the default as the recommended op- also suggests this is an impactful area for more study. For example,

tion because it reflects the most-commonly-chosen option or fits integrating loss aversion and framing effects into risk probability

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by VIRGINIA TECH UNIVERSTIY on 05/02/16. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

within the social norm (Brown and Krishna 2004; McKenzie et al. formulas, as part of Cumulative Prospect Theory, led to higher

2006). People maintaining these norms are more likely to preserve profit margins on a small hypothetical project (Cattell et al. 2011).

the default choice (Kahneman 2013). Reference dependence means In another example from the construction literature, optimism bias,

the default frames the outcome as a loss or gain and, as with risk or undervaluing the probability of risk, contributed to productivity

framing, this impacts the decision (Dinner et al. 2010). The 401(k) estimating errors (Son and Rojas 2011). In both of these examples,

investor who invests less than the 3% default, most likely, feels bad researchers call for a greater connection between understanding hu-

about this decision. The investor who chooses to invest more, most man behavior and construction decisions, which is a connection

likely, feels better about this decision. The feeling of good or bad is that choice architecture can help strengthen.

dependent on the choice architects default. Researchers studying infrastructure systems either already

Like organ donation, defaults in construction can also save lives. know, or can identify, the highest-impact decisions and their deter-

minants at individual, organizational, and societal levels. These

Residential building codes ensure life and property safety and are

high-impact decisions are a good place to start. Researchers can

reviewed, amended, and then adopted by individual counties or

also identify which choice architecture interventions are most plau-

cities. However, in counties or cities lacking resources or knowl-

sible for adoption by various stakeholder groups. For example,

edge, code review boards are often not in place, which means there

changing how a law is written is more difficult than changing

are no safety and health design minimums. Illinois corrected this

how a request for proposal (RFP) is written, so all else being equal,

problem by setting a statewide building code default. Counties can

an intervention focused on a RFP could be prioritized.

opt-in or opt-out of the statewide codes but counties not taking Various methods can be used to study choice architecture inter-

action automatically opt-in (Monte 2012). Texas is the opposite. ventions. As in many of the enduring behavioral science studies,

Without a statewide default, many counties outside of the large infrastructure researchers can use classroom experiments with

municipalities are not protected by codes, thus allowing engineers stakeholders represented by studentswho use infrastructure

and contractors to design to no minimum health and life standards and will eventually make decisions that shape it. Of course, infra-

(Building Codes: Rating the States 2013). Changing the default structure decisions are subject to varying constraints, goals, and

could reduce the effort individual counties need to make and protect resources with different stakeholder schedules, agendas, mandates,

both life and property by setting a strong reference for minimum and budget cycles. Therefore, a complete picture requires evaluat-

standards. ing behavioral influences on multiple stakeholder groups. For that

reason, in addition to experimental studies with students, more-

qualitative methods such as case studies are needed to understand

Conclusions and Future Research Opportunities decision-makers, such as elected officials and city planners, who

are less numerous but just as influential. Regardless of the method

This article has shown some of the many ways in which choice used, the systematic merging of behavioral science and infrastruc-

architecture can improve infrastructure outcomes. The outcome ture systems described in this article allows readers to investigate

of interest was elegance but readers can draw parallels to imagine choice architecture as a strategy to influence the infrastructure

how choice architecture may influence other desirable outcomes. outcomes they desire.

Indeed, opportunities abound for infrastructure professionals to

build choice architecture into the planning and design processes

that lead to infrastructure systems. The framing of choices can Acknowledgments

evoke different feelings and thus influence decisions. Probabilities,

risk, and uncertainty shift perceived value when framed as a loss The authors are grateful for their ongoing research partnership

or gain. By highlighting, or framing system attributes, engineers with Elke Weber, Eric Johnson, Edy Moulton-Tetlock, and Ruth

can guide decisions in the best interest of the user and in the best Greenspan Bell. Their insight and selfless collaboration shaped

interest for the system. Feedback loops and goal-setting can shape the research described in this paper. This material is based in part

user performance. Partitioning options can reduce the number of on work supported by The National Science Foundation, through

decisions, and defaults can remove the need to make any decision Grants 1054122 and 1531041. Any opinions, findings, and conclu-

at all. sions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of

Furthermore, these choice architecture interventions have the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National

relatively small barriers to implementation. Simply changing the Science Foundation.

default of sustainability rating system to start from the lowest level

(zero points) to higher levels of achievement can reframe the

decision process to account for loss aversion. Such a change costs

References

nothing to implement and leads to greater achievement in score Abdellatif, M., and Al-Shammaa, A. (2015). Review of sustainability in

(Shealy and Klotz 2015). buildings. Sustainable Cities Soc., 14, 171177.

ASCE 04016023-7 J. Infrastruct. Syst.

J. Infrastruct. Syst., 04016023

Allcott, H., and Mullainathan, S. (2010). Behavior and energy policy. Duchon, D., Dunegan, K. J., and Barton, S. L. (1989). Framing the prob-

Science, 327(5970), 12041205. lem and making decisions: The facts are not enough. IEEE Trans. Eng.

Anastasopoulos, P., McCullouch, B., Gkritza, K., Mannering, F., and Sinha, Manage., 36(1), 2527.

K. (2010). Cost savings analysis of performance-based contracts Eckerson, C. (2006). San Francisco: Removal of the embarcadero

for highway maintenance operations. J. Infrastruct. Syst., 10.1061/ freeway. http://www.streetfilms.org/lessons-from-san-francisco/

(ASCE)IS.1943-555X.0000012, 251263. (Aug. 6, 2006).

Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably irrational: The hidden forces that shape our Eckerson, C. (2007). Interview with Enrique Penalosa. http://www

decisions, HarperCollins, New York. .streetfilms.org/interview-with-enrique-penalosa-long/ (Feb. 1, 2007).

Arkes, H. R., and Blumer, C. (1985). The psychology of sunk cost. Ecotect 1 [Computer software]. Autodesk, San Rafael, CA.

Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes, 35(1), 124140. Eisenberg, D., and Persram, S. (2009). Code, regulatory and systemic bar-

Beamish, T., and Biggart, N. (2010). Social heuristics: Decision making riers affecting living building projects. https://ilbi.org/education/

and innovation in a networked production market. http://papers.ssrn reports/codestudy3 (Mar. 3, 2016).

.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1533429 (Mar. 3, 2016). El-Diraby, T. (2013). Civil infrastructure decision making as a chaotic

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by VIRGINIA TECH UNIVERSTIY on 05/02/16. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

Beamish, T. D., and Biggart, N. W. (2012). The role of social heuristics in sociotechnical system: Role of information systems in engaging stake-

project-centred production networks: Insights from the commercial holders and democratizing innovation. J. Infrastruct. Syst., 10.1061/

construction industry. Eng. Project Organiz. J., 2(12), 5770. (ASCE)IS.1943-555X.0000165, 355362.

Becker, F., and Parsons, K. S. (2007). Hospital facilities and the role of Ellison, G., and Ellison, S. F. (2009). Search, obfuscation, and price

evidence-based design. J. Facil. Manage., 5(4), 263274. elasticities on the internet. Econometrica, 77(2), 427452.

Benartzi, S., and Thaler, R. H. (1995). Myopic loss aversion and the equity Elster, J. (1989). Social norms and economic theory. J. Econ. Perspect.,

premium puzzle. Q. J. Econ., 110(1), 7392. 3(4), 99117.

Billows, S. A. (1999). The role of elegance in system architecture and Fox, C. R., and Tversky, A. (1998). A belief-based account of decision

design. S.M. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, System under uncertainty. Manage. Sci., 44(7), 879895.

Design and Management Program, Cambridge, MA. Gardner, G. T., and Stern, P. C. (2008). The short list: The most effective

Bocchini, P., Frangopol, D., Ummenhofer, T., and Zinke, T. (2014). actions U.S. households can take to curb climate change. Enviro.: Sci.

Resilience and sustainability of civil infrastructure: Toward a Policy Sustainable Dev., 50(5), 1225.

unified approach. J. Infrastruct. Syst., 10.1061/(ASCE)IS.1943- Genesove, D., and Mayer, C. (2001). Loss aversion and seller behavior:

555X.0000177, 04014004. Evidence from the housing market. Q. J. Econ., 116(4), 12331260.

Bolar, A., Tesfamariam, S., and Sadiq, R. (2014). Management of civil Goette, L., Huffman, D., and Fehr, E. (2004). Loss aversion and labor

infrastructure systems: QFD-based approach. J. Infrastruct. Syst., supply. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc., 2(23), 216228.

10.1061/(ASCE)IS.1943-555X.0000150, 04013009. Gonzalez, C., Dana, J., Koshino, H., and Just, M. (2005). The framing

Brown, C. L., and Krishna, A. (2004). The skeptical shopper: A metacog- effect and risky decisions: Examining cognitive functions with fMRI.

nitive account for the effects of default options on choice. J. Consum. J. Econ. Psychol., 26(1), 120.

Res., 31(3), 529539. Green Homeowner. (2016). Attitudes and preferences for remodeling and

Brydges, B. (2016). The fixed-price of failure? http://www buying green homes by McGraw Hill construction. http://www

.morganfranklin.com/website/assets/uploads/documents/MFC_Fixed .librarything.com/work/9813635 (Mar. 3, 2016).

PriceofFailure_Web.pdf (Mar. 3, 2016). Hardisty, D. J., Johnson, E. J., and Weber, E. U. (2010). A dirty word or a

Buonomano, D. (2012). Brain bugs: How the brains flaws shape our lives, dirty world? Attribute framing, political affiliation, and query theory.

W.W. Norton, New York. Psychol. Sci., 21(1), 8692.

Cabeza, L. F., Castell, A., Medrano, M., Martorell, I., Prez, G., and Hardman, D. (2009). Judgment and decision making: Psychological

Fernndez, I. (2010). Experimental study on the performance of perspectives, Wiley, Malden, MA.

insulation materials in Mediterranean construction. Energy Build., Hastings, J. S., and Weinstein, J. M. (2008). Information, school choice,

42(5), 630636. and academic achievement: Evidence from two experiments. Q. J.

Camerer, C. F. (2004). Prospect theory in the wild: Evidence from Econ., 123(4), 13731414.

the field. Advances in behavioral economics, C. F. Camerer, G. Heath, C., Larrick, R. P., and Wu, G. (1999). Goals as reference points.

Loewenstein, and M. Rabin, eds., Princeton University Press, Princeton, Cognit. Psychol., 38(1), 79109.

NJ, 148161. Heath, C., and Tversky, A. (1991). Preference and belief: Ambiguity

Carmon, Z., and Ariely, D. (2000). Focusing on the forgone: How value and competence in choice under uncertainty. J. Risk Uncertainty, 4(1),

can appear so different to buyers and sellers. J. Consum. Res., 27(3), 528.

360370. Hilbert, M. (2012). Toward a synthesis of cognitive biases: How noisy

Carney, D. R., and Banaji, M. R. (2012). First is best. PLoS One, 7(6), information processing can bias human decision making. Psychol.

e35088. Bull., 138(2), 211237.

Cattell, D., Bowen, P., and Kaka, A. (2011). Proposed framework for Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety. (2013). Building

applying cumulative prospect theory to an unbalanced bidding model. codes: Rating the States. http://www.disastersafety.org/building

J. Constr. Eng. Manage., 10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000367, _codes/rating-the-states_ibhs/ (Dec. 13, 2013).

10521059. Iyengar, S. S., and Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating:

Chalifoux, A. (2006). Using life cycle costing and sensitivity analysis to Can one desire too much of a good thing? J. Pers. Social Psychol.,

sell green building features. J. Green Build., 1(2), 3948. 79(6), 9951006.

Cho, Y., Alaskar, S., and Bode, T. (2010). BIM-integrated sustainable Jacowitz, K. E., and Kahneman, D. (1995). Measures of anchoring in

material and renewable energy simulation. Construction Research estimation tasks. Pers. Social Psychol. Bull., 21(11), 11611166.

Congress 2010, ASCE, Reston, VA, 288297. Johnson, E. J. (1993). Framing, probability distortions, and insurance

Cummings, R. G., Brookshire, D. S., Bishop, R. C., and Arrow, K. J. decisions. J. Risk Uncertainty, 7(1), 3551.

(1986). Valuing environmental goods: An assessment of the contingent Johnson, E. J., et al. (2012). Beyond nudges: Tools of a choice architec-

valuation method, Rowman and Allanheld, Lanham, MD. ture. Marketing Lett., 23(2), 487504.

Dinner, I. M., Johnson, E. J., Goldstein, D. G., and Liu, K. (2010). Johnson, E. J., and Goldstein, D. (2003). Do defaults save lives? Science,

Partitioning default effects: Why people choose not to choose, Social 302(5649), 13381339.

Science Research Network, Rochester, NY. Johnson, E. J., Hubl, G., and Keinan, A. (2007). Aspects of endowment:

Dobson, J. K., and Griffin, J. A. (1992). Conservation effect of immediate A query theory of value construction. J. Exp. Psychol.: Learn. Memory

electricity cost. Feedback on residential consumption behavior. Proc., Cognit., 33(3), 461474.

7th ACEEE Summer Study on Energy Efficiency in Buildings, American Kahneman, D. (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping

Council for an Energy Efficient Economy, Washington, DC. bounded rationality. Am. Psychol., 58(9), 697720.

ASCE 04016023-8 J. Infrastruct. Syst.

J. Infrastruct. Syst., 04016023

Kahneman, D. (2013). Thinking, fast and slow, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Framing effects and group processes. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis.

New York. Processes, 108(2), 242255.

Kahneman, D., and Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of Monte, S. (2012). Champaign county building code feasibility study and

decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263291. implementation strategies. Champaign County, IL, http://www.co

Kahneman, D., and Tversky, A. (1984). Choices, values, and frames. Am. .champaign.il.us/pandz/120423CCBuildingCodeFeasibilityStudyImpl

Psychol., 39(4), 341350. Strategies.pdf (Mar. 3, 2016).

Kahneman, D., and Tversky, A. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Moody, S., and Melia, S. (2013). Shared spaceResearch, policy and

Cumulative representation of uncertainty. J. Risk Uncertainty, 5(4), problems. Proc. ICETransp., 167(6, 384392.

297323. Niece, S. (2005). 6% limitation on design services upheld, and failure

Khawarzad, A. (2011). Using Ciclovia to plan your streets [projects for to estimate construction costs results in U.S. contract being found

public space]. http://www.pps.org/blog/using-ciclovia-to-plan-your void. http://www.constructionweblinks.com/resources/industry_reports

-streets/ (Apr. 8, 2011). __newsletters/May_30_2005/sixp.html (May 30, 2005).

Kling, J. R., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E., Vermeulen, L. C., and Wrobel, Nincic, M. (1997). Loss aversion and the domestic context of military

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by VIRGINIA TECH UNIVERSTIY on 05/02/16. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

M. V. (2012). Comparison friction: Experimental evidence from intervention. Political Res. Q., 50(1), 97120.

Medicare drug plans. Q. J. Econ., 127(1), 199235. Norquist, J. (2000). Tear it down! Democratic leadership councils

Klotz, L. (2010). Cognitive biases in energy decisions during the planning, blueprint. http://www.preservenet.com/freeways/FreewaysTear.html

design, and construction of commercial buildings in the U.S.: An ana- (Sep. 1, 2000).

lytical framework and research needs. Energy Effic., 4(2), 271284. Novemsky, N., and Kahneman, D. (2005). The boundaries of loss

Klotz, L., Mack, D., Klapthor, B., Tunstall, C., and Harrison, J. (2010). aversion. J. Marketing Res., 42(2), 119128.

Unintended anchors: Building rating systems and energy performance OCass, A., and McEwen, H. (2004). Exploring consumer status and

goals for U.S. buildings. Energy Policy, 38(7), 35573566. conspicuous consumption. J. Consum. Behav., 4(1), 2539.

Kluger, A. N., and DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interven- Odean, T. (1998). Are investors reluctant to realize their losses?

tions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a J. Finance, 53(5), 17751798.

preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychol. Bull., 119(2), OECD (Organizations for Economic Co-Operation and Development).

254284. (2013). Public investment (Economic Policy Reforms 2013).

Knetsch, J. L. (1989). The endowment effect and evidence of nonrevers- http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/graph/growth-2013-graph177-en

ible indifference curves. Am. Econ. Rev., 79(5), 12771284. (Mar. 3, 2016).

Larrick, R. P., and Soll, J. B. (2008). The MPG illusion. Science, Ogawa, R. T., and Malen, B. (1991). Towards rigor in reviews of multiv-

320(5883), 15931594. ocal literature: Applying the exploratory case method. Rev. Educ. Res.,

Levav, J., Heitmann, M., Herrmann, A., and Iyengar, S. S. (2010). Order 61, 265286.

in product customization decisions: Evidence from field experiments. Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., and Johnson, E. J. (1993). The adaptive

J. Political Econ., 118(2), 274299. decision maker, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.

Levin, I. P., and Gaeth, G. J. (1988). How consumers are affected by Press, E. (2011). Bogotas bountiful protected bikeways. http://www

the framing of attribute information before and after consuming the .streetfilms.org/riding-bogotas-bountiful-protected-bikeways/ (Aug. 8,

product. J. Consum. Res., 15(3), 374378. 2011).

Levin, I. P., Schneider, S. L., and Gaeth, G. J. (1998). All frames are Rick, S. (2011). Losses, gains, and brains: Neuroeconomics can help to

not created equal: A typology and critical analysis of framing effects. answer open questions about loss aversion. J. Consum. Psychol., 21(4),

Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes, 76(2), 149188. 453463.

Levy, J. S. (1996). Loss aversion, framing, and bargaining: The implica- Shamosh, N. A., and Gray, J. R. (2008). Delay discounting and intelli-

tions of prospect theory for international conflict. Int. Political Sci. gence: A meta-analysis. Intelligence, 36(4), 289305.

Rev., 17(2), 179195. Shealy, T., and Klotz, L. (2015). Well-endowed rating systems: How

Loftness, V. (2013). Investing in energy efficiency for economic, environ- modified defaults can lead to more sustainable performance. J. Constr.

mental, and human benefits. Engineering Sustainability, Univ. of Eng. Manage., 10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001009, 04015031.

Pittsburgh, Mascron Center for Innovation, Pittsburgh. Shiv, B., Loewenstein, G., Bechara, A., Damasio, H., and Damasio, A. R.

Madni, A. M. (2012). Elegant systems design: Creative fusion of simplic- (2005). Investment behavior and the negative side of emotion.

ity and power. Syst. Eng., 15(3), 347354. Psychol. Sci., 16(6), 435439.

Madrian, B. C., and Shea, D. F. (2001). The power of suggestion: Inertia Shore, F. (2010). Shared space: Operational assessment (No. C3783100).

in 401(k) participation and savings behavior. Q. J. Econ., 116(4), http://assets.dft.gov.uk/publications/ltn-01-11/ltn-1-11-quantitative.pdf

11491187. (Mar. 3, 2016).

Manvel, E. (2011). The Mayoral candidates and the costly, risky CRC. Siegel, A. M., and Etzkorn, I. (2013). Simple conquering the crisis of com-

http://www.blueoregon.com/2011/10/mayor-on-crc/ (Sep. 19, 2013). plexity. http://www.contentreserve.com/TitleInfo.asp?ID={4FC8BB97

Marteau, T. M. (1989). Framing of information: Its influence upon deci- -F026-4456-8DE4-872360B9CC12}&Format=410 (Mar. 3, 2016).

sions of doctors and patients. Br. J. Social Psychol., 28(1), 8994. Smith, C. (2010). Natures longing for beauty: Elegance as an evolution-

Martin, J. M., and Norton, M. I. (2009). Shaping online consumer choice ary attractor, with implications for human systems. World Futures,

by partitioning the Web. Psychol. Marketing, 26(10), 908926. 66(7), 504510.

Martino, B. D., Kumaran, D., Seymour, B., and Dolan, R. J. (2006). Sokol-Hessner, P., Camerer, C. F., and Phelps, E. A. (2012). Emotion

Frames, biases, and rational decision-making in the human brain. regulation reduces loss aversion and decreases amygdala responses

Science, 313(5787), 684687. to losses. Social Cognit. Affective Neurosci., 8(3), 341350.

May, M. E. (2009). In pursuit of elegance: Why the best ideas have some- Son, J., and Rojas, E. (2011). Impact of optimism bias regarding organi-

thing missing, Broadway Books, New York. zational dynamics on project planning and control. J. Constr. Eng.

McGraw, A. P., Larsen, J. T., Kahneman, D., and Schkade, D. (2010). Manage., 10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000260, 147157.

Comparing gains and losses. Psychol. Sci., 21(10), 14381445. Strack, F., Martin, L., and Schwarz, N. (1988). Priming and communica-

McKenzie, C. R. M., Liersch, M. J., and Finkelstein, S. R. (2006). tion: Social determinants of information use in judgments of life

Recommendations implicit in policy defaults. Psychol. Sci., 17(5), satisfaction. Eur. J. Social Psychol., 18(5), 429442.

414420. Sunstein, C. R. (2015). Nudging and choice architecture: Ethical

McNichol, T. (2004). Roads gone wild. http://www.wired.com/2004/12/ considerations. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Papers.cfm?abstract_id=

traffic/ (Mar. 3, 2016). 2551264 (Mar. 3, 2016).

Milch, K. F., Weber, E. U., Appelt, K. C., Handgraaf, M. J., and Krantz, D. Thaler, R. H. (1980). Toward a positive theory of consumer choice.

H. (2009). From individual preference construction to group decisions: J. Econ. Behav. Organiz., 1(1), 3960.

ASCE 04016023-9 J. Infrastruct. Syst.

J. Infrastruct. Syst., 04016023

Thaler, R. H., and Benartzi, S. (2004). Save more tomorrow (TM): Using Wald, M. L. (2007). Things fall apart, but some big old things dont.

behavioral economics to increase employee saving. J. Political Econ., http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/12/weekinreview/12wald.html

112(S1), S164S187. (Aug. 12, 2007).

Thaler, R. H., and Sunstein, C. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about Walker, R., Pettitt, J., Scruggs, K., and Mlakar, P. (2014). Data

health, wealth, and happiness, Yale University Press, New York. collection and organization by smartphone for infrastructure assess-

Thaler, R. H., Sunstein, C. R., and Balz, J. P. (2010). Choice architecture ment. J. Infrastruct. Syst., 10.1061/(ASCE)IS.1943-555X.0000166,

(SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 1583509). http://papers.ssrn.com/ 06013001.

abstract=1583509 (Mar. 3, 2016). Weber, E. U. (2006). Experience-based and description-based perceptions

The Economist. (2007). Sunk infrastructure. http://www.economist.com/ of long-term risk: Why global warming does not scare us (yet). Clim.

blogs/freeexchange/2007/08/sunk_infrastructure (Sep. 18, 2013).

Change, 77(12), 103120.

Todd, A., and Houde, S. (2011). List of behavioral economics principles

Weber, E. U., Johnson, E. J., Milch, K. F., Chang, H., Brodscholl, J. C.,

that can inform energy policy. http://www.annikatodd.com/List_of

and Goldstein, D. G. (2007). Asymmetric discounting in intertemporal

_Behavioral_Economics_for_Energy_Programs.pdf (Mar. 3, 2016).

choice: A query-theory account. Psychol. Sci., 18(6), 516523.

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by VIRGINIA TECH UNIVERSTIY on 05/02/16. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

van Buiten, M., and Hartmann, A. (2013). Public-private partnerships:

Cognitive biases in the field. http://www.epossociety.org/EPOC2013/ Wilson, C., and Dowlatabadi, H. (2007). Models of decision making

Papers/VanBuiten_Hartmann.pdf (Mar. 3, 2016). and residential energy use. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour., 32(1),

Vanderbilt, T. (2008). The traffic guru. Wilson Q., 32(3), 2632. 169203.

van Houwelingen, J. H., and van Raaij, W. F. (1989). The effect of Yi-Rong, N., et al. (2011). Dissociated brain organization for two-digit

goal-setting and daily electronic feedback on in-home energy use. addition and subtraction: An fMRI investigation. Brain Res. Bull.,

J. Consum. Res., 16(1), 98105. 86(56), 395402.

ASCE 04016023-10 J. Infrastruct. Syst.

J. Infrastruct. Syst., 04016023

You might also like

- 2014 Flynn Onondaga PDFDocument12 pages2014 Flynn Onondaga PDFanitazhindonNo ratings yet

- 2012 Lemonick PDFDocument4 pages2012 Lemonick PDFanitazhindonNo ratings yet

- Yasuni ITT InitiativeDocument7 pagesYasuni ITT InitiativeanitazhindonNo ratings yet

- Happy Cities BogotaDocument7 pagesHappy Cities BogotaanitazhindonNo ratings yet

- The Practice of Biophilic DesignDocument27 pagesThe Practice of Biophilic DesignRobert Dozsa100% (4)

- Suburban Nation PDFDocument12 pagesSuburban Nation PDFanitazhindonNo ratings yet

- Suburban Nation PDFDocument12 pagesSuburban Nation PDFanitazhindonNo ratings yet

- Yasuni ITT InitiativeDocument7 pagesYasuni ITT InitiativeanitazhindonNo ratings yet

- From MDGs To SDGs Lancet June 2012Document6 pagesFrom MDGs To SDGs Lancet June 2012bercer7787No ratings yet

- The Charrette As An Agent For Change: 2.1 Work CollaborativelyDocument4 pagesThe Charrette As An Agent For Change: 2.1 Work CollaborativelyanitazhindonNo ratings yet

- 2012 Lemonick PDFDocument4 pages2012 Lemonick PDFanitazhindonNo ratings yet

- Sway FramesDocument29 pagesSway FramesanitazhindonNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Log of Outputs q3 En9Document5 pagesLog of Outputs q3 En9ShyneGonzalesNo ratings yet

- Ivandic Odyssey 2022Document1,208 pagesIvandic Odyssey 2022ria.ivandicNo ratings yet

- Integrity What It Is and Why It Is ImportantDocument16 pagesIntegrity What It Is and Why It Is ImportantJean Rose LasolaNo ratings yet

- Culture Visual PercepcionDocument15 pagesCulture Visual PercepcionDavid MastrangeloNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking in The NewsDocument33 pagesCritical Thinking in The Newsapi-448017533No ratings yet

- Types of BiasDocument2 pagesTypes of BiasAli GhanemNo ratings yet

- Making the Right Career ChoiceDocument2 pagesMaking the Right Career ChoiceNannu KardamNo ratings yet

- Capstone Project-Grainger and Bosch: Digital Marketing CampaignDocument25 pagesCapstone Project-Grainger and Bosch: Digital Marketing Campaignk.saikumar100% (1)

- Final Examination Convert To Coursework - An Individual Essay QuestionsDocument21 pagesFinal Examination Convert To Coursework - An Individual Essay QuestionsNayama NayamaNo ratings yet

- Annotated Works CitedDocument4 pagesAnnotated Works Citedapi-289138299No ratings yet

- Dirty Data and Bad PredictionDocument30 pagesDirty Data and Bad PredictionkartiknirwanNo ratings yet

- Management 8th Edition Kinicki Test BankDocument28 pagesManagement 8th Edition Kinicki Test Bankjohnnavarronpisaoyzcx100% (21)

- Palaroan Theorypaper1Document7 pagesPalaroan Theorypaper1api-438185399No ratings yet

- Chapter 6Document38 pagesChapter 6priyamNo ratings yet

- The Complexity of Multiparty Negotiations: Wading Into The MuckDocument9 pagesThe Complexity of Multiparty Negotiations: Wading Into The MuckIvan PetrovNo ratings yet

- Employee Perception Project Report - 152617288Document60 pagesEmployee Perception Project Report - 152617288pradnya kharat100% (6)

- Barriers To Effective CommunicationDocument33 pagesBarriers To Effective Communicationshumaila parveenNo ratings yet

- Critical ThinkingDocument16 pagesCritical Thinkingstanchell100% (2)

- Performance Assessment Plan - EXAM DURANDocument2 pagesPerformance Assessment Plan - EXAM DURANVan DuranNo ratings yet

- A Hypothesis-Confirming Bias in Labeling Effects: John M. Darley and Paget H. GrossDocument14 pagesA Hypothesis-Confirming Bias in Labeling Effects: John M. Darley and Paget H. GrossMarcus LoNo ratings yet

- Environmental Communication Seminar Groups (With Allocation of Cognitive Biases)Document2 pagesEnvironmental Communication Seminar Groups (With Allocation of Cognitive Biases)Muhammad Dhiya UlhaqNo ratings yet

- PhiloDocument27 pagesPhiloMaria Angelica BermilloNo ratings yet

- Nursing Research-For Validator EvaluationDocument9 pagesNursing Research-For Validator EvaluationKatherine 'Chingboo' Leonico Laud100% (1)

- Piaget's Cognitive Development Theory Highlighted by SchemasDocument54 pagesPiaget's Cognitive Development Theory Highlighted by SchemasheartofhomeNo ratings yet

- Writing An Argumentative EssayDocument35 pagesWriting An Argumentative EssayEries KenNo ratings yet

- Custom Essay Writing Service ReviewsDocument5 pagesCustom Essay Writing Service Reviewsejqdkoaeg100% (2)

- Biases Due To The Retrievability of Instances. When The Size of A Class Is Judged by TheDocument6 pagesBiases Due To The Retrievability of Instances. When The Size of A Class Is Judged by TheThạchThảooNo ratings yet

- Dropout NationDocument5 pagesDropout Nationapi-481575064No ratings yet

- Removal of An Arbitrator For Reasonable Apprehension of Bias - Password - RemovedDocument15 pagesRemoval of An Arbitrator For Reasonable Apprehension of Bias - Password - RemovedEmadNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document9 pagesChapter 2HenryNo ratings yet