Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 - 5 - Unit #1 Lecture, Part 2 (12 - 48)

Uploaded by

piece_of_mindzz19690 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views7 pages1248

Original Title

1 - 5 - Unit #1 Lecture, Part 2 (12_48)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document1248

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views7 pages1 - 5 - Unit #1 Lecture, Part 2 (12 - 48)

Uploaded by

piece_of_mindzz19691248

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

[MUSIC].

Alright folks, so some of our dirty

little secrets are now out.

We've talked so far about what

archaeology isn't.

It's not all about digging, it's not

about working just in exotic places.

It's not all about the past and so on.

So it's probably time to start talking

about what archaeology is.

So, to do that let's think about the

structure of this class.

In each unit we're going to ask and

answer some very basic questions.

First, and most fundamental you know,

what actually survives for archaeologists

to find and just how does that survival

happen?

How do we find things? By accident, spy

satellites?

And once we've found something, how do we

investigate it?

Do we dig it?

Leave it alone?

Re-bury it?

And how might we figure out how old it

is?

What on earth do you do with it?

And what if it is a dead body?

Who gets to be an archaeologist and where

do they work?

And, most basically and hardest of all,

who owns the past?

How do we manage it, how do we sell it?

So it's question on question, problem on

problem and, as you'll soon see, there

are very rarely straight-forward,

unquestionably correct answers to any of

them.

So to quickly sample these questions,

kind of give a preview of the course as a

whole, lets quickly look at just one

place.

One of the most famous archaeological

sites in the world.

And that is Pompeii in Italy.

The plan here is to use Pompeii,

you see an aerial view, as a case study.

To ask and answer the sort of core

questions of the class.

Unit by unit.

So unit two.

What survives for archaeologists to find?

And just how does that happen?

Now as you see before you at Pompeii the

answer is lots.

Pompeii is notorious, of course, for it's

terrible fate.

It was buried by the eruption of the

volcano you see in the background.

Mount

Vesuvius which, apparently, is getting

active again.

Making some people pretty nervous.

And what was once a bustling city was

smothered, literally blanketed by several

meters of volcanic debris.

You see here the stratigraphy of the

eruption, the strata, the layers of

deposition.

So this blanket killed, but it also

preserved.

We have food, furniture, sidewalks,

beware of the dog signs.

You get a very real sense the immediacy

of the lives that were lost.

So Pompeii is a spectacular example of

sad fact, and another one of our dirty

little secrets, that archeologists often

benefit from strange occurrences, unusual

conditions and sometimes tragic events.

So unit three, how do you find things?

Archaeology isn't just digging.

Now at Pompeii, people who lived in the

area in the centuries after the eruption

of Vesuvius, knew, they knew that

something was down there.

They would find things in their fields

for example.

It's a good example of the power of local

knowledge, of local informants in

archaeology.

Still today many discoveries start with

conversations, conversations over coffee,

over beer, asking people, you seen

anything old around?

And maybe they will tell you, and maybe

they won't.

Now, if we discovered Pompeii today, the

question of how to investigate it would

be a, a tough one to answer, and I think

would lead to lots of controversy.

Should we excavate this dead city?

How should we dig it?

How much should we dig of it?

Should we just leave the place alone to

preserve it for future generations?

What lies behind this turmoil is a very

basic fact, one that is, it is essential

you take on board now, because while

excavation is very revealing, very

informative, and often the only way to

learn what you want to know, it is also

destructive.

As you dig, you destroy what you are

digging.

And you can't go back and try it again.

So archaeological ethics today demand

that we consider as many non-destructive,

non-invasive forms of investigation

first, and only then do we go for the

shovels.

Now that is what would happen if Pompeii

was found today.

Unfortunately, archaeology at Pompeii

started long ago far back as the 18th

century.

And another dirty little secret.

The early days of archaeology were pretty

much out of control when it came to what

we today would consider good practice.

Early days of exploration at the site

were what you could kind of call a slash

and burn archeology, people very much out

to find goodies.

diggers would go in, often by tunneling,

and they would just pull out nice things:

statues, metal objects, paintings.

You see tunnels here, and you see

paintings literally just cut out of the

wall.

[SOUND] Taken away, and this has led to

enormous damage to the site, and the loss

of archaeological context.

That context where something is found.

Where, when what it was found with we've

talked about this.

Without context objects lose most of

their ability to tell a story.

And to tell the story of the people who

made, used and discarded them.

The loss of archaeological context is the

problem of problems.

It's the archaeologist's worst nightmare.

Thankfully, however over time

archaeological methodologies evolved

with definite improvement over the course

of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Today there is much emphasis, for the most

part anyway,

on data recording, on new forms of

documentation of context, on site

conservation and site preservation.

Let's turn to Unit Four.

How do you get a date and why do you need

them?

Dating the destruction of Pompeii is not

hard.

We know thanks to first-person historical

accounts that it occurred in AD 79.

Or 79 CE.

That's an absolute date.

On the other hand, that's just the

destruction level.

That's only one moment in Pompeii's long

chronology.

How could we date, for example, when

people first lived at Pompeii?

When were certain houses built?

Which temple is older that which?

We need for, other forms of absolute and

relative dating.

And fortunately, there are an increasing

number of scientific ways to get at such

information.

What, and here comes Unit Five, what do

you do with what you find?

Now the answers to that question are many

and various, and very dependent on what

those finds are.

There are also many stages of activity to

consider.

Finding something is just the beginning

of a lengthy process.

Things come out of the ground.

They may need to be conserved so they

don't immediately fall apart.

They need to be documented, described,

drawn, photographed, scanned.

They need to be analyzed.

They need to be published, or otherwise

shared.

Archaeologists have an ethical obligation

to make their data available.

We'll talk a lot more about this.

But, you want to know another dirty

little secret?

The vast majority of archaeological finds

sit in boxes in storage.

And after their initial study, if they

get initial study, no one ever looks them

again.

And that's something to think about.

Others, however, make the big time and

end up in museums and in exhibitions.

Pompeii, of course, is always a big draw,

lots of cool things, tragic story line,

Romans are always sexy and so on.

But that, in turn, raises issues of how

we present the past and we'll come back

to that in a minute.

Unit Six - what's involved in the

archaeology of people?

What if what you find are human remains?

Now Vesuvius left us many victims though

there's not much mystery about how they

died.

But, what about how they lived?

For example what did they eat?

At Pompeii we can actually see some last

meals like that bread.

Left on tables.

Or, and indeed better, bio-archaeologists

today can get, can gain senses of diet

and overall health from looking at

physical remains, particularly skeletal

remains.

So palaeopathology, pathologies of the

past is one way to interrogate social

conditions.

Did it matter?

If you were rich or poor, male or female,

free or slave, when it came to your diet

and your health.

And the answer, then as now, was

absolutely yes.

Now, not all of these victims of Vesuvius

can be studied in that fashion the

exploration of skeletal remains.

At Pompeii, for example, the bodies were

covered by the fall of ash, which

hardened around the body.

And the body then eventually decomposed.

Archaeologists digging the site began to

notice cavities in the ash and they came

up with the idea of pouring in plaster,

or other material, and the result as you

see, often in startling detail, is the

shape of the missing person.

these are evocative and painful to look

at as are the deaths of the other

inhabitants of the city, its animals.

Probably the most famous is this dying

dog of Pompeii chained up and left to its

death.

If the people don't get you, if the

people don't tug at your heart strings,

the doggy will.

Unit Seven.

Where does archaeology happen?

And who can play?

Pompeii is not the only buried city in

archaeology.

Other sites have been smothered by

volcanoes.

You see here the famous site of Akrotiri, on the island of Thera in Greece.

There are also sites in India, Costa

Rica, Tanzania, Canada and the United

States.

And as we will see, sites can be buried

and preserved by other slightly less

drastic and dramatic means as well.

So Pompeii is not unique, but it remains

highly unusual in the number of people

who work at it, visit it, worry about it.

The site operates under the authority of

a government ministry.

Various archaeological projects, both

Italian and foreign, are ongoing.

Numerous non-profit organizations

contribute money for its conservation.

But above all, there are the tourists.

How many people annually do you think

Pompeii has attracted in recent years?

Some 2.5 million visitors annually and

some days see as many as 20,000 people

walking through the entrance gates.

Now is this a good thing?

Good that people are interested in the

past?

Yes.

But, visitor numbers combined with

restrictive resources for conservation and

site protection and conservation, is

leading to what's been called, the Second

Death of Pompeii.

People marching through at thousands,

billions of feet annually.

Wearing away these ancient streets,

touching things, leaning against walls,

bumping into wall painting with their

backpacks.

Helping themselves to little souvenirs.

Most recently structures at Pompeii have

actually started to collapse.

They just plain fall down.

All and all it's impossible to deny that

Pompeii today looks much older than it

did just 50 years ago.

It just can't take the strain of its

celebrity status.

And Pompeii is a perfect object lesson of

how once a site is dug and exposed.

It takes a lot of time,

effort, and money to save it from the

inevitable forces of decay.

Things just want to fall apart.

So what do we do here?

I'm going to ask you to comment on this

question in the discussion forums.

What might work, what's worked at other

places you've visited?

But let me put one idea out there, for

the sake of argument.

Just shut down the site.

Public keep out.

Close Pompeii off to everyone but real

scholars, people who can understand and

appreciate what they are looking at,

PhD's, like me.

I can get in, you can't.

You can go to the gift shop.

What do you make of that idea?

Looking at Pompeii opens up a Pandora's

box of legal rights and ethical

responsibilities.

Issues that apply to all sites, not just

the biggies, not just the famous ones,

all sites of human cultural heritage.

Who gets to tell the stories?

Who has the right to see?

Who has the obligation to protect?

Where should archaeological loyalties

primarily lie?

To the past, to the present, or to the

future?

In other words, Unit Eight and the end of

the class and the final secret of the

class, who owns the past?

[BLANK_AUDIO]

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Collected Letters of Flann O'BrienDocument640 pagesThe Collected Letters of Flann O'BrienSean MorrisNo ratings yet

- 5 - 18 - People, Places, Things - Levantine Rock Art - Archaeoacoustics (5 - 14)Document2 pages5 - 18 - People, Places, Things - Levantine Rock Art - Archaeoacoustics (5 - 14)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 5 - 5 - Demonstration - Metals (8 - 31)Document6 pages5 - 5 - Demonstration - Metals (8 - 31)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- Torrent Downloaded From Katcr - Co - KickasstorrentsDocument1 pageTorrent Downloaded From Katcr - Co - Kickasstorrentspiece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 142 01 PDFDocument5 pages142 01 PDFthonyyanmuNo ratings yet

- 5 - 3 - Demonstration - Lithics, Part 1 (5 - 07)Document3 pages5 - 3 - Demonstration - Lithics, Part 1 (5 - 07)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 5 - 6 - Demonstration - Pottery, Part 1 (7 - 00)Document5 pages5 - 6 - Demonstration - Pottery, Part 1 (7 - 00)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 5 - 13 - Conversations - Montserrat, Part 5 (5 - 50)Document4 pages5 - 13 - Conversations - Montserrat, Part 5 (5 - 50)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 5 - 16 - People, Places, Things - Chaco Canyon (6 - 12)Document4 pages5 - 16 - People, Places, Things - Chaco Canyon (6 - 12)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 5 - 15 - Conversations - El Zotz, Part 5 (6 - 16)Document4 pages5 - 15 - Conversations - El Zotz, Part 5 (6 - 16)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 5 - 4 - Demonstration - Lithics, Part 2 (6 - 14)Document4 pages5 - 4 - Demonstration - Lithics, Part 2 (6 - 14)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 5 - 11 - Demonstration - 3D Modeling, Part 3 (9 - 22)Document4 pages5 - 11 - Demonstration - 3D Modeling, Part 3 (9 - 22)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 3 - 13 - Conversations - Sagalassos, Part 2 (5 - 46)Document4 pages3 - 13 - Conversations - Sagalassos, Part 2 (5 - 46)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 5 - 12 - Conversations - Abydos, Part 5 (10 - 00)Document7 pages5 - 12 - Conversations - Abydos, Part 5 (10 - 00)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 5 - 9 - Demonstration - 3D Modeling, Part 1 (3 - 39)Document2 pages5 - 9 - Demonstration - 3D Modeling, Part 1 (3 - 39)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 7 - 2 - Unit #7 Lecture (7 - 52)Document4 pages7 - 2 - Unit #7 Lecture (7 - 52)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 6 - 3 - Demonstration - Human Bones, Part 1 (9 - 06)Document6 pages6 - 3 - Demonstration - Human Bones, Part 1 (9 - 06)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 3 - 6 - Demonstration - Google Earth (8 - 07)Document5 pages3 - 6 - Demonstration - Google Earth (8 - 07)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 5 - 12 - Conversations - Abydos, Part 5 (10 - 00)Document7 pages5 - 12 - Conversations - Abydos, Part 5 (10 - 00)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 5 - 5 - Demonstration - Metals (8 - 31)Document6 pages5 - 5 - Demonstration - Metals (8 - 31)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 4 - 12 - People, Places, Things - Kotylaion Olive Press (7 - 44)Document4 pages4 - 12 - People, Places, Things - Kotylaion Olive Press (7 - 44)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 3 - 9 - Conversations - Abydos, Part 3 (7 - 32)Document6 pages3 - 9 - Conversations - Abydos, Part 3 (7 - 32)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 3 - 10 - Conversations - Montserrat, Part 3 (5 - 32)Document4 pages3 - 10 - Conversations - Montserrat, Part 3 (5 - 32)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 3 - 14 - People, Places, Things - Machu Picchu (6 - 30)Document4 pages3 - 14 - People, Places, Things - Machu Picchu (6 - 30)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 6 - 2 - Demonstration - Animal Bones (9 - 50)Document5 pages6 - 2 - Demonstration - Animal Bones (9 - 50)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 6 - 17 - Case Study - Psychic Archaeology (6 - 15)Document4 pages6 - 17 - Case Study - Psychic Archaeology (6 - 15)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 6 - 18 - People, Places, Things - Fayum Portraits (6 - 47)Document4 pages6 - 18 - People, Places, Things - Fayum Portraits (6 - 47)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 6 - 15 - Conversations - El Zotz, Part 6a (10 - 34)Document6 pages6 - 15 - Conversations - El Zotz, Part 6a (10 - 34)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 6 - 15 - Conversations - El Zotz, Part 6a (10 - 34)Document6 pages6 - 15 - Conversations - El Zotz, Part 6a (10 - 34)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 6 - 2 - Demonstration - Animal Bones (9 - 50)Document5 pages6 - 2 - Demonstration - Animal Bones (9 - 50)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 6 - 6 - Demonstration - Human Bones, Part 4 (4 - 25)Document3 pages6 - 6 - Demonstration - Human Bones, Part 4 (4 - 25)piece_of_mindzz1969No ratings yet

- 8086 Microprocessor: J Srinivasa Rao Govt Polytechnic Kothagudem KhammamDocument129 pages8086 Microprocessor: J Srinivasa Rao Govt Polytechnic Kothagudem KhammamAnonymous J32rzNf6ONo ratings yet

- CAM TOOL Solidworks PDFDocument6 pagesCAM TOOL Solidworks PDFHussein ZeinNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Vivekananda Flyover BridgeDocument8 pagesCase Study On Vivekananda Flyover BridgeHeta PanchalNo ratings yet

- Issue 189Document38 pagesIssue 189Oncampus.net100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S0959652619316804 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0959652619316804 MainEmma RouyreNo ratings yet

- Löwenstein Medical: Intensive Care VentilationDocument16 pagesLöwenstein Medical: Intensive Care VentilationAlina Pedraza100% (1)

- Team Dynamics and Behaviors for Global ExpansionDocument15 pagesTeam Dynamics and Behaviors for Global ExpansionNguyênNo ratings yet

- Marriage Gift PolicyDocument4 pagesMarriage Gift PolicyGanesh Gaikwad100% (3)

- Biotechnology Eligibility Test (BET) For DBT-JRF Award (2010-11)Document20 pagesBiotechnology Eligibility Test (BET) For DBT-JRF Award (2010-11)Nandakumar HaorongbamNo ratings yet

- Performance of a Pelton WheelDocument17 pagesPerformance of a Pelton Wheellimakupang_matNo ratings yet

- Rev F AvantaPure Logix 268 Owners Manual 3-31-09Document46 pagesRev F AvantaPure Logix 268 Owners Manual 3-31-09intermountainwaterNo ratings yet

- Speech TravellingDocument4 pagesSpeech Travellingshafidah ZainiNo ratings yet

- Programming Language II CSE-215: Dr. Mohammad Abu Yousuf Yousuf@juniv - EduDocument34 pagesProgramming Language II CSE-215: Dr. Mohammad Abu Yousuf Yousuf@juniv - EduNaruto DragneelNo ratings yet

- Expected OutcomesDocument4 pagesExpected OutcomesPankaj MahantaNo ratings yet

- Funny Physics QuestionsDocument3 pagesFunny Physics Questionsnek tsilNo ratings yet

- An Improved Ant Colony Algorithm and Its ApplicatiDocument10 pagesAn Improved Ant Colony Algorithm and Its ApplicatiI n T e R e Y eNo ratings yet

- Describing An Object - PPTDocument17 pagesDescribing An Object - PPThanzqanif azqaNo ratings yet

- MMH Dan StoringDocument13 pagesMMH Dan Storingfilza100% (1)

- PSAII Final EXAMDocument15 pagesPSAII Final EXAMdaveadeNo ratings yet

- Conservation of Kuttichira SettlementDocument145 pagesConservation of Kuttichira SettlementSumayya Kareem100% (1)

- OV2640DSDocument43 pagesOV2640DSLuis Alberto MNo ratings yet

- Abend CodesDocument8 pagesAbend Codesapi-27095622100% (1)

- Network Theory - BASICS - : By: Mr. Vinod SalunkheDocument17 pagesNetwork Theory - BASICS - : By: Mr. Vinod Salunkhevinod SALUNKHENo ratings yet

- Plumbing Arithmetic RefresherDocument80 pagesPlumbing Arithmetic RefresherGigi AguasNo ratings yet

- UTC awarded contracts with low competitionDocument2 pagesUTC awarded contracts with low competitioncefuneslpezNo ratings yet

- IBM Systems Journal PerspectivesDocument24 pagesIBM Systems Journal PerspectivesSmitha MathewNo ratings yet

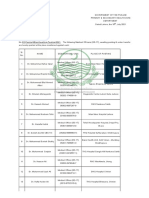

- Government of The Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare DepartmentDocument3 pagesGovernment of The Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare DepartmentYasir GhafoorNo ratings yet

- Amo Plan 2014Document4 pagesAmo Plan 2014kaps2385No ratings yet

- 37 Operational Emergency and Abnormal ProceduresDocument40 pages37 Operational Emergency and Abnormal ProceduresLucian Florin ZamfirNo ratings yet