Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tting Out of Our Conceptual Ruts - Strategies For Expanding Conceptual Frameworks

Uploaded by

Edwin GilOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tting Out of Our Conceptual Ruts - Strategies For Expanding Conceptual Frameworks

Uploaded by

Edwin GilCopyright:

Available Formats

Getting Out of Our Conceptual Ruts

Strategies for Expanding Conceptual Frameworks.

Allan W. Wicker Claremont Graduate School

ABSTRACT: The human tendency to think recurring 2. Researchers should consider contexts. They

thoughts limits our theories and research. This article can place specific problems in a larger domain, make

presents four sets of strategies that may be useful for comparisons outside the problem domain, examine

generating new perspectives on familiar research processes in the settings in which they naturally occur,

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

problems: playing with ideas, considering contexts, consider the practical implications of research, and

probing and tinkering with assumptions, and clarifying probe library resources.

and systematizing the conceptual frame. 3. It is important for researchers to probe and

tinker with assumptions through such techniques as

exposing hidden assumptions, making the opposite

In 1879, Sir Francis Galton published an article de- assumption, and simultaneouslytrusting and doubting

scribing a leisurely stroll he took in the interests of the same assumption.

science--specifically to explore how the mind works. 4. Finally, it is vital that researchers clarify and

In the article, Galton told of walking down a London systematize their conceptual frameworks. They

street and scrutinizing every object that came into his should scrutinize the meanings of key concepts, spec-

view. He recorded the first thought or two that oc- ify relationships among concepts, and write a concept

curred to him as he focused on each of about 300 paper.

objects. Galton reported that this method produced The need for psychologists to attend to concep-

a great variety of associations, including memories of tual framing processes has been widely acknowledged

events that had occurred years earlier. (see, for example, Brinberg & McGrath, 1985;

After several days, Galton repeated the walk and Campbell, Daft, & Hulin, 1982; Caplan & Nelson,

the recording procedure and again found a variety of 1973; Gergen, 1978, 1982; Jones, 1983; McGuire,

associations. He also discovered a great deal of rep- 1973, in press; Tyler, 1983; Wachtel, 1980; Weick,

etition or overlap in his thoughts on the two occasions. 1979).

Galton likened his thoughts to actors in theater Several caveats are in order before we proceed:

processions in which the players march off one side 1. Some readers may already be familiar with

of the stage and reappear on the other. This recurrence certain strategies and find them obvious. I have tried

of ideas piqued Galton's curiosity. He next devised to include a diversity of heuristics in the hope that

some word association tasks that led him to the same even seasoned investigators will find something of

conclusion as his walks, namely, that "the roadways value.

of our minds are worn into very deep ruts" (Galton, 2. Given the goal of presenting a range of strat-

1879, cited by Crovitz, 1970, p. 35). egies, only limited space is available for describing

Although Galton's methods may have been faulty and illustrating each procedure. There is a risk that

by present standards, he seems to have discovered a important and complex topics have been oversimpli-

stable psychological principle: the recurrence of ideas fied-possibly even trivialized. I strongly recommend

(Crovitz, 1970). My comments here assume that Gal- further reading on any strategy that seems promising;

ton was rightwthat our thoughts flow in a limited references are provided in the text.

number of channels and that our research efforts are 3. These strategies are offered as heuristics. Most

thereby constrained. have not been systematicallyevaluated, although they

This article sketches a variety of approaches for have been useful to the scholars who proposed them

stimulating new insights on familiar research prob- and to others who have used them.

lems. Four sets of strategies, phrased as advice to re- 4. The substantial and important psychological

searchers, are discussed as follows: literature on problem solving and critical and creative

1. Researchers should play with ideas through a thinking has not been reviewed or even cited here.

process of selecting and applying metaphors, repre- Much of that research addresses problems for which

senting ideas graphically, changing the scale, and at- there are consensual solutions derived from mathe-

tending to process. matical or other logical systems. And some of that

1094 October 1985 American Psychologist

Copyright 1985 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 00034)66X/85/$00.75

Vol. 40, No. 10, 1094-1103

literature presumes that thinking habits developed and subtleties inherent in their domains (Weick,

from work on abstract puzzles or exercises are readily 1979). For example, likening interpersonal attraction

transferable to a wide range of other problems. The to magnetic fields, a performance of Swan Lake, sym-

present concern is how to generate useful ideas whose biosis, and hypnotism may reveal significant aspects

"accuracy" cannot immediately be assessed. The fol- of personal relationships that are not considered by

lowing strategies draw upon, and in some cases ex- such established perspectives as social exchange and

pand, the researcher's existing knowledge structures equity theories.

(cf. Glaser, 1984). They are directly applicable to re-

search problems in all areas of psychology. Represent Ideas Graphically

A casual scan of such journals as Science, American

Play with Ideas Scientist, and Scientific American suggests that re-

A playful, even whimsical, attitude toward exploring searchers in the physical and biological sciences make

ideas is appropriate for the first set of strategies. These greater use of graphic presentations than do psychol-

strategies include working with metaphors, drawing ogists. We may be overlooking a powerful tool. In the

sketches, imagining extremes, and recasting entities developmental stages of a research problem, a pad of

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

as processes. large drawing paper and a set of multicolored pens

may be more useful than a typewriter. Visual images

Select and Apply Metaphors and sketches of problems can be liberating to re-

Playing with metaphors can evoke new perspectives searchers accustomed to representing their ideas only

on a problem. One strategy for exploiting metaphors in linear arrangements of words, sentences, and para-

is to identify some features from the research domain graphs. Kurt Lewin, who used diagrams extensively,

that are also discernible in another domainhperhaps reportedly was ecstatic upon discovering a three-col-

another discipline or area of activity. Attention is ored automatic pencil, which he carried everywhere

shifted to this new area (the metaphor), which is then to sketch his ideas (R. G. Barker, personal commu-

closely examined. From this examination, the re- nication, April 10, 1983).

searcher may discover some variables, relationships, Many kinds of graphic schemes can be used to

or patterns that can usefully be translated back to the explore ideas and communicate them to others. Tab-

research problem. ular grids, organization charts, flow diagrams, topo-

A productive metaphor in social psychology is logical regions, and schematics are examples of ab-

McGuire's inoculation theory of resistance to per- stract graphic languages. They have their own gram-

suasion. The metaphor used was the medical proce- mar and syntax and can be used to portray a variety

dure of stimulating bodily defenses against massive of contents (McKim, 1972; Nelms, 1981). Figure 1

viral attacks by inoculating individuals with weakened illustrates the flow diagram; it simply and clearly pre-

forms of the virus. This procedure suggested the pos- sents the three main approaches researchers have

sibility of increasing resistance to persuasion by pre- taken in studying relations between behavioral and

senting weak arguments before strong arguments are somatic variables.

encountered (McGuire, 1964). (The heuristic value

of metaphors is discussed in Gowin, 1981b; Smith, I

1981; and Weick, 1979. Leary, 1983, has analyzed the Figure 1

role of metaphor in the history of psychology. See A Graphic Representation of Three Approaches to

Lakoff& Johnson, 1980, for a readable philosophical/ Research on the Relation Between Behavioral and

linguistic analysis of metaphors.) Somatic Variables

Exploring multiple, unusual metaphors may lead Behavioral_

researchers to a greater awareness of the complexities nterventlon~

I am grateful to the students who have participated in my graduate

seminar, Applied Conceptual Framing and Analysis, for assistance Behavlo ral Somatic

in evaluating numerous conceptual refraining strategies, including Correlational

the ones presented here. I also acknowledge an intellectual debt to

variables ] approach [ varlables

Karl E. Weick, whose various published works have stimulated my

thinking more than is evident from the citations in this article.

Valuable comments on previous drafts of this article were provided

by several anonymous reviewers and the following colleagues: Roger

G. Barker, Dale E. Berger, Arthur H. Brayfield, Robyn M. Dawes,

Robert S. Gable, Jeanne Kin~ Mark W. Lipsey, Edward Ostrander,

and Kathleen O'Brien Wicker. Note, From "Experience, Memory, and the Brain" by M. R. Rosenzweig,

Correspondence should be addressed to Allan W. Wicker, Fac- 1984, American Psychologist, 39, p. 366. Copyright 1984 by American

Psychological Association. Reprinted by permission.

ulty in Psychology, Claremont Graduate School, Claremont, CA

91711.

October 1985 American Psychologist 1095

In freehand idea sketching, there are no rules to (in press) has recast the behavior setting concept from

be followed. With practice, researchers can fluently a relatively stable "given" to a more dynamic entity

represent and explore their ideas and boldly experi- that develops over a series of life stages and in response

ment with relationships just as artists, composers, and to changing internal and external conditions.

urban planners have profitably done (McKim, 1972).

Change the Scale Consider Contexts

Imagining extreme changes in proportion can stim- The strategies in this section direct researchers' atten-

ulate our thinking. Mills (1959) gave this advice: "If tion to the extended social world in which psycholog-

something seems very minute, imagine it to be simply ical events occur. These strategies are not theoretically

enormous, and ask yourself: What difference might neutral. They advance a viewpoint that has been ex-

that make? And vice versa, for gigantic phenomena" pressed in ecological and environmental psychology

(p. 215). He then asked readers to imagine what pre- (e.g., Barker, 1968; Stokols, 1982; Wicker, in press)

literate villages might have been like with 30 million and that has been stated more generally in terms of

inhabitants. Or, to take another example, consider how the implications for psychology of the new "realist"

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

philosophy of science (e.g., Georgoudi & Rosnow,

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

child-rearing would be different if at birth children

had the motor ability and strength of adults. And if 1985; Manicas & Secord, 1983). The style of thought

there were no memory loss, how would human in- promoted here contrasts with much that is typical in

formation processing be different? psychology, but it can broaden our perspectives and

A variation of this procedure is to imagine what suggest alternatives to traditional practices and ways

would be required for a perfect relationship to exist of thinking.

between two variables presumed to be linked. For ex-

Place Specific Problems in a Larger Domain

ample, psychologists have often assumed that a per-

son's expressed attitudes determine how he or she will Researchers can use this strategy to decide where to

behave in daily affairs (Cohen, 1964). However, for begin work in a new area and to plan new research

people to act in complete accordance with their at- directions. The goal is to map out the broader domain

titudes, they would have to be independently wealthy, of which an existing or contemplated study is only a

to have unlimited time at their disposal, to have no part. Once the boundaries and features of a conceptual

regard for the opinions of others, to be unaffected by territory have been charted, judgments can be made

unforeseen chance occurrences, to have a wide range about which areas are most promising for further ex-

o f high-level skills, and even to be in several places atploration.

once (Wicker, 1969). Reflections on such factors can Such mapping of a research problem depends

lead to more realistic theories and expectations. upon the researcher's current conceptual frame and

upon a variety of information sources, such as intu-

Attend to Process

ition, theory, and research findings. An early step is

Research psychologists typically favor concepts that to specify the boundaries of the broader domain at

represent stable entities, perhaps because such con- an appropriate level of abstraction. For example, in

cepts are easier to measure and to incorporate into one of several case studies cited by McGrath (1968)

theories than are processes. Yet it can be fruitful to to illustrate this strategy, the domain was bounded by

view presumably stable concepts in dynamic terms. criteria for the mental health of emotionally disturbed

One systematic approach that can help us focus on patients.

process is the tagmemic method from the field of Once the domain has been defined, the next step

rhetoric: The same unit of experience is regarded al- is to identify the major factors or influences that bear

ternatively as a "particle" (a thing in itself), a "wave" on the topic. Each of the major factors can then be

(a thing changing over time), and as part of a field (a analyzed into its components or attributes, and a sys-

thing in context; Young, Becket, & Pike, 1970). tematic classification scheme can be developed. By

A related strategy is changing nouns into verbs, examining all logical combinations of attributes, in-

or as Weick (1979) advised, "think 'ing.'" Many con- vestigators can plan research to cover appropriate--

cepts in our research vocabularies are nouns: percep- perhaps neglected--aspects of the problem. In

tion, organization, social norm. Weick suggested McGrath's (1968) example, three main factors were

imagining such concepts not as stable entities but as identified and analyzed into components: (a) sources

dynamic processes, constantly in flux, continually of data on patients' mental health, whose components

being reconstructed through accretion and erosion. included self-reports, ratings by staff, and observations

Changing nouns to verbs may promote process im- in standard and uncontrived situations; (b) modes of

agery. Thus, one would speak of perceiving, organiz- behavior, including motor, cognitive, emotional, and

ing, and "norming." social; and (c) temporal frame of measurement, in-

In a recent application of this strategy, Wicker cluding measures of immediate treatments, overall

1096 October 1985 American Psychologist

hospital stay, and posthospital adjustment. This con- What we regard as basic social and cognitive processes

ceptual framework helped guide a study of how pa- are conditioned by cultural and historical factors

tients were affected by their move to a new hospital (Gergen, 1982; Mills, 1959; Segall, Campbell, & Her-

building. skovitz, 1966). Researchers who focus on contem-

A set of components applicable to most research porary events in Western culture can profitably ex-

domains consists of actors, behaviors, and contexts amine similar events in other periods and cultures.

(Runkel & McGrath, 1972). Actors may be individ- Guttentag and Secord's (1983) recent elaboration of

uals, groups, organizations, or entire communities. social exchange theory to include social structural

Behaviors are actions that actors undertake toward variables provides an illustration: Social exchange

objects. Contexts are immediate surroundings of ac- theorists have regarded participants in dyadic inter-

tors and their behaviors, including time, place, and actions as free agents capable of negotiating the most

condition. Each component would be further subdi- favorable outcomes for themselves. Using data from

vided into aspects appropriate to the research domain. several cultures and historical periods, the investiga-

Laying out the components and their subdivisions in tors demonstrated that the demographic condition of

a grid produces a domain "map" on which any par- disproportionate sex ratios (substantially more men

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

ticular investigation can be located. For example, the than women in a particular population, or vice versa)

following factors could be used in a classification directly affected the exchange process between men

scheme for group problem solving: members' abilities and women. For example, when men outnumbered

and motives, type of tasks performed, relationships women, men were less likely to enter or stay in a mo-

among members, group staffing levels, and type of nogamous heterosexual relationship. Women might

settings in which groups perform. either cater to men or withdraw from them to express

Developing a comprehensive framework for a female independence (Guttentag & Secord, 1983; Se-

research domain contrasts with the more prevalent cord, 1984). (More general treatments of theoretical

"up and out" strategy, in which investigators link their and methodological issues in historical and cross-cul-

work on relatively narrow, focused topics with events tural research are found in Gergen & Gergen, 1984,

outside their domain and then transpose their frame- and Malpass, 1977.)

work and findings to this new area. For example, re- We can also probe the structure of contemporary

search on students' verbal reactions to brief intervals society for subtle influences on how we frame research

of crowding has been extrapolated to prisons, homes, topics. Sampson (1981) was concerned that psychol-

and transportation systems. An analysis of crowding ogists interpet and present socially and historically

using the three components mentioned above would limited events as fundamental properties of the human

reveal many additional factors that could be consid- mind. He argued that the predominant psychological

ered and incorporated into subsequent research. Ac- world view portrays people as independent agents

tors could be expanded to include prisoners and whose primary functions are ruminations--cognitive

homemakers; behaviors could include social inter- activities such as planning, wishing, thinking, orga-

action and task performance; contexts could include nizing, and problem solving--with little regard for

living quarters, worksites, recreational settings, and the objective social world. Furthermore, he contended

time frames of months or years. Some research on that such a view may not only be time bound, but

crowding reflects these broader considerations (e.g., may also serve to reaffirm present societal arrange-

Cox, Paulus, & McCain, 1984). ments and values. Sampson's advocacy of a "critical

study of psychology and society, a study that is self-

Make Comparisons Outside the Problem Domain conscious about its context, its values, and its rela-

We are familiar with the principle that knowledge is tionship to human freedom (p. 741)" has numerous

an awareness of differences--it is our rationale for and profound implications for many specific research

using control groups. This principle can be invoked domains. Theories of work motivation, for example,

to generate new ideas: Comparisons can be made with may need to consider the worker's psychological state

actors, behaviors, or settings outside one's current and the organizational, legal, economic, cultural, and

problem domain. For example, Piotrkowski (1978) even nutritional conditions under which work is per-

has provided insights into family interaction patterns formed (cf. Barrett & Bass, 1976).

by examining the nature of.the work that family Parenthetically, it is worth noting that academic

members perform both inside and outside the home. disciplines and research specialties may also benefit

The emotional availability of family members to one from "outside" influences; for example, requirements

another may depend less on their personalities than in graduate programs for coursework outside the ma-

on the quality and timing of their work experiences, jor field (Lawson, 1984), cross-disciplinary collabo-

such as how stressful and fatiguing the work is and ration, and serious efforts to include perspectives o f

whether overtime and late shift work is involved. women, ethnic minorities, gays, and scholars from

More remote comparisons may also be fruitful. developing countries.

October 1985 American Psychologist 1097

Examine Processes in the Settings in of direct observation of behaviors in context. (Obser-

Which They Naturally Occur vational strategies are discussed by Lofland, 1976, and

Most psychological and behavioral processes unfold Weick, 1968.)

Ideally, researchers who wish to consider con-

in behavior settings (taken-for-granted configurations

textual factors would first identify and then represen-

of time, place, and objects where routine patterns of

tatively sample settings where the behaviors of interest

behavior occur) such as offices, workshops, hospital

regularly occur (cf. Brunswik, 1947; Petrinovich,

waiting rooms, parks, and worship services (Barker,

1979). But such an extensive effort may not be nec-

1968). These small-scale, commonsense units of social

essary to gain insights from behavioral contexts. In-

organization variously promote, afford, permit, en-

vestigators might observe people in a few settings

courage, and require behaviors that are part of or are

where the behaviors or processes of interest are a sig-

compatible with the main activity, and they discourage

nificant part of the program. For example, workers'

or prohibit behaviors that interfere with it.

adjustments to stress can be studied in police dis-

By contrast, much psychological research is con-

ducted in contrived environments that lack the char- patcher worksites (Kirmeyer, 1984).

Ventures out of the laboratory can reveal ne-

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

acteristics of behavior settings. Table 1 illustrates some

glected but significant influences on a behavior or

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

differences between features of a typical laboratory

study of small groups (see Miller, 1971) and a behavior process. For example, an environmental psychologist

interested in personal space might, by observing peo-

setting.

ple in medical office waiting rooms, discover that

In some psychological specialties, theories are

people's sense of what is a comfortable distance from

formulated and may be revised on the basis of gen-

others depends on how ill they feel, on whether the

erations of studies conducted exclusively in the lab-

others may have contagious diseases, and on furniture

oratory. Recognized experts may lack firsthand ex-

arrangements and design, including whether chairs

perience with the events and subjects that produce

have armrests.

their data (cf. Jones, 1983). Yet the work of such sem-

inal figures as Piaget and Lewin illustrates the benefits Consider Practical Implications o f Research

Reflections on how research might be applied also

Table 1 can lead to expanded views of basic psychological

Contrast Between a Typical Small Group Study processes. For example, theories and findings on hu-

and Behavior Setting Features man learning and memory can be used to design in-

structional materials. Through such efforts, previously

Typical small group study Behavior setting features

unseen gaps in existing frameworks might become

Fixed duration, 1 hour or Indefinite duration, evident and could lead to broadened research pro-

less typically months or cedures. Stimulus materials could be made more

years complex and more natural, response alternatives in-

Group composed of Staff composed of creased and made more meaningful, time frames ex-

college students community members panded, and tasks and environments made more re-

No prior interaction Extensive prior alistic (Mackie, 1974). Designed applications could

among group members interaction among staff be discussed with practitioners and then be imple-

members

mented and evaluated.

Imposed task, often an Endogenous tasks,

intellectual problem to typically involving Probe Library Resources

be solved behavior objects such

as equipment and One of the most accessible vehicles for transcending

supplies narrow conceptual frames is the research library,

Casual interactions Meaningful interactions whose extensive resources are scarcely considered by

No enduring local culture Established local culture many researchers. As psychologists, we may limit our

No hierarchical Hierarchical relationships literature searches to work listed in the Psychological

relationships among among members Abstracts or even to a few select journals. If so, we

members

are ignoring enormous amounts of potentially useful

Closed system: no Open system: changes in

personnel changes, not personnel, part of a information and sources of ideas from the larger social

part of a system system network that world.

network including includes suppliers, The resources include both quantitative and

suppliers, external external information qualitative data. Baseline data and other statistics rel-

information sources, sources, and recipients evant to most research topics can usually be found.

and recipients of of products For example, the Statistical Abstract of the United

products States (1985), published annually by the Bureau of

the Census, includes national data on health, educa-

1098 October 1985 American Psychologist

tion, housing, social services, the labor force, energy, memory theories and recent laboratory-based re-

transportation, and many other topics. It also contains search to suggest a new term (repisodic) for memories

a guide to other statistical publications. that are accurate in general substance but inaccurate

Statistics such as these can provide perspectives in their detail (Neisser, 1981).

not generally available in the psychological literature.

They can, for example, show trends in the frequency Probe and Tinker With Assumptions

and distribution of events. Such data can suggest new

research directions: A researcher might choose to give Virtually any conceptual framework, methodology,

greater emphasis to cases that are more frequent, use or perspective on a problem incorporates judgments

more resources, have more beneficial or detrimental that are accepted as true, even though they may not

consequences, affect more people, or are on the leading have been confirmed. Probing and tinkering with these

edge of an important trend or development. Re- assumptions can stimulate thinking in productive di-

searchers of legal decision making might, for example, rections. Strategies considered here include making

be influenced by the following facts: (a) In each of the hidden assumptions explicit, making opposing as-

past several years, less than 7% of civil cases before sumptions, and simultaneously trusting and discred-

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

U.S. District Courts came to trial, and (b) from 1965 iting the same assumption.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

to 1983, the percentage of cases (civil and criminal

cases combined) tried by jury in these courts declined Expose Hidden Assumptions

from 51% to 40% (Statistical Abstract of the United The task of revealing our own implicit assumptions

States, 1985, pp. 178-179). Researchers of mock ju- is inherently difficult and can never be fully accom-

ries might profitably expand their work to include plished. Some assumptions may be imbedded in ev-

other aspects of legal decision making such as pretrial eryday or technical language, and others may be tied

negotiations and the ways that judges consider and into our sensory and nervous systems. About all we

weigh evidence. (Bibliographies of useful statistical can hope for is an increased awareness of a small por-

sources are found in Bart & Frankel, 1981; and Cot- tion of the assumptive network. And to probe any

tam & Pelton, 1977.) assumption, we must trust many others (Campbell,

Libraries are also a bountiful source of qualita- 1974).

tive information on the range of human experience The contrastive strategy--juxtaposing dissimilar

and behavior. These data take many forms: newspa- elements from alternative or competing perspectives--

pers and magazines, popular nonfiction, oral histories, is one way to uncover hidden assumptions. The jux-

legal cases, ethnographies, diaries and letters, atlases, taposition can also lead to more precise statements

novels, and photographs, as well as the scholarly lit- of one or both conceptual frameworks. The conditions

erature. Such materials can be sampled and analyzed under which the alternative perspectives are most ap-

much as a sociological field worker selects and studies plicable may thus be clarified (McGuire, in press). To

people and events in a community. Qualitative infor- illustrate, two theories make contradictory predictions

mation in libraries can be perused at the researcher's about how staff members respond when service set-

convenience, and it often covers extended time peri- tings such as child day care facilities and emergency

ods, allowing for analyses of trends. (The use of library medical services are understaffed. One theory (Barker,

data in theory building is discussed by Glaser & 1968) predicted a positive response: The staffwill work

Strauss, 1967, chapter 7.) harder, will assume additional responsibilities, and will

The benefits of consulting a broad range of have increased feelings of self-worth and competence.

sources are evident in Heider's (1958/1983) influential Another theory (Milgram, 1970) predicted such neg-

book, The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. In ative responses as disaffection with the work and dis-

an attempt to document and systematize the layper- regard for clients' individual needs and low-priority

son's knowledge of social relationships, Heider drew claims for attention. Both theories are likely to be

upon the works of philosophers, economists, novelists, correct in certain circumstances. Positive responses

humorists--and social scientists. For example, he may occur in settings where understaffing is infrequent

credited the 17th century philosopher Spinoza for the and known to be temporary, whereas negative re-

insights that led to his statement of cognitive balance. sponses may characterize settings where there is a

An illustration of the creative use of qualitative chronic shortage of staff members (Wicker, 1979/

data in a psychological specialty where laboratory in- 1983). In this case, the theorists apparently made dif-

vestigations predominate is Neisser's (1981) study of ferent implicit assumptions about the frequency and

the memory of former presidential counsel John duration of understaffing.

Dean. Neisser compared Dean's testimony before the Allison's (1971) analysis of governmental deci-

Senate Watergate Investigating Committee with sub- sion making during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis

sequently revealed transcripts of the conversations illustrates the benefits of applying different conceptual

Dean had testified about. Neisser's analysis drew upon perspectives to the same set of events. He demon-

October 1985 American Psychologist 1099

strated that certain actions were best explained by sider this latter assumption may become more sen-

assuming that the various branches of the American sitive to differences in populations and conditions and

and Soviet governments (such as the U.S. Navy and may even become interested in developing taxonomies

the Soviet KGB) followed their standard operating that would be useful for specifying limits of generality.

procedures. Other actions were better understood as An argument along these lines has been advanced

"'resultants" of pulling and hauling by political players by McKelvey (1982). He stated that management

within the governments. Both perspectives were con- theorists and academic social scientists (notably social

trasted with the more commonly accepted "rational psychologists and sociologists) routinely advance

actor model," which presumes that governmental ac- principles that they assume are applicable to orga-

tions are chosen after reviews of the costs and benefits nizations in general. In a provocative challenge to this

o f alternatives (Allison, 1971). assumption, McKelvey drew upon evolutionary the-

ory to propose an "organizational species" concept,

Make the Opposite Assumption "dominant competence," that he believed could be

A more playful strategy is to recast an explicit as- used to build a taxonomy of organizations.

sumption into its opposite and then to explore the Numerous recognized theoretical contributions

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

implications o f the reversal. A general procedure for in psychology can be viewed as articulated denials of

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

recasting theoretical assumptions has been suggested existing assumptions. For example, Barker's (1963)

by Davis (1971), who contended that theories are classic article introducing behavior settings was es-

judged interesting when they challenge the assumption sentially a rejection of the view that human environ-

ground o f an audience. He identified 12 general ways ments are disordered, unstable, and without obvious

of recasting theoretical statements (see Table 2). boundaries. And Zajonc's (1965) analysis of social

The following example illustrates the general- facilitation was a demonstration that seemingly in-

local contrast from Davis's list. Many research psy- compatible research findings can coexist in a frame-

chologists assume that if they empirically test a hy- work that distinguishes between responses that are

pothesized relationship and the predicted result is ob- high and low in the subject's response hierarchy.

tained, they confirm not only that particular rela-

Simultaneously Trust and Doubt

tionship but also the higher level conceptual the Same Assumption

hypothesis and the general theory from which it was

derived. An opposing assumption is that demonstrated Our thinking becomes more complicated when we

effects are conceptually local, that is, limited to a sub- devalue what we believe:

set o f populations and/or conditions similar to those Any person who has a view of the world and who also dis-

in the investigation. Researchers who seriously con- credits part of that view winds up with two ways to examine

a situation. Discrediting is a way to enhance requisite variety

and a way to register more of the variety that's present in

Table 2 the world. (Weick, 1979, p. 228)

Ways of Recasting Theoretical Statements

Researchers can use this device to introduce flexibility

What something seems to be What it is in reality (or vice versa) and ambivalence into their conceptual framework--

they can trust an assumption for some purposes and

Disorganized Organized distrust it for others. The strategy has both theoretical

Heterogeneous Composed of a single and methodological applications. For example, when

element

A property of persons A property of a larger

attempting to explain the behavior of people over their

social system life span, a personality theorist might presume that

Local General actions are guided by a few enduring behavioral dis-

Stable and Unstable and changing positions (traits), but when considering how people

unchanging act on a specific occasion the theorist might doubt

Ineffective Effective that traits are useful. Or a researcher might devise

Bad Good and administer a questionnaire or interview schedule

Unrelated Correlated on the assumption that people respond openly and

Coexisting Incompatible freely, but interpret the responses in a way that as-

Positively correlated Negatively correlated sumes people respond primarily in guarded and self-

Similar Opposite

serving ways.

Cause Effect

Note. Adapted from "That's Interesting: Toward a Phenomenology of So- Clarify and Systematize the

ciology and a Sociology of Phenomenology" by M. S. Davis, 1971, Phi-

Iosophy of the Social Sciences, 1, pp. 309-314. Copyright 1971 by Wilfred

Conceptual Framework

Laurier University Press. Adapted by permission Most of the above strategies will expand the research-

er's conceptual framework. At some point the enlarged

1 I00 October 1985 American Psychologist

set of ideas should be reviewed to select the most pro- hypothetico-deductive systems, are well known to

vocative thoughts for further, more intensive analysis. psychologists. Other procedures such as concept

The following procedures can be helpful in this sifting mapping can also be used to simplify and clarify a

process as well as earlier in the conceptual framing research domain. Figure 2 illustrates a concept map;

process. it represents Gowin's ( 1981 a) theory of educating. The

first step in producing such a map is to list the major

Scrutinize the Meanings of Key Concepts concepts that are part of a developing framework or

theory. The concepts are then ranked in order of im-

Researchers should have and communicate a clear

portance. This order is preserved in the concept map,

understanding of the concepts they use. One way to

with the most important concept at the top, and so

clarify meanings of key terms is to explore their roots,

on. Concepts are placed in boxes, and relationships

synonyms, and earliest known uses. Numerous

among concepts are indicated by lines and brief verbal

sources are available, including dictionaries (etymo-

descriptions (Gowin, 198 la, pp. 93-95).

logical, unabridged, reverse, technical), technical

In another variation of concept mapping, arrows

books, handbooks, and encyclopedias. The nuances

are used to show a presumed direction of causality,

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

in meaning revealed by these sources can help research-

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

and signs (+, - ) are used to show whether the influ-

ers choose terms that precisely express their ideas. Con-

ence is positive or negative. From the pattern of such

sider, for example, the nuances implicit in the root

relationships, inferences can be drawn about the do-

meanings of these related words: educate (to rear or

main being considered; for example, whether a system

bring up), instruct (to construct or arrange), teach (to

is amenable to change, and if so, where change efforts

show, guide, or direct), and train (to pull, draw, or drag)

might be directed (Maruyama, 1963; Weick, 1979,

(Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the

68-88).

English Language, Unabridged, 1969).

Theorists need to be sensitive to the different Write a Concept Paper

levels of generality that are implied by their concepts. Perhaps the most powerful tool for ordering and clar-

Often it is advisable to examine terms at more than ifying thinking is putting one's ideas into words.

one level. Abstract terms can often be broken into Writing is so familiar and often so burdensome that

components whose various meanings are worth ex- we often overlook or avoid it until we feel ready to

ploring. For example, health-promoting behavior may communicate with an audience. Writing should be

include several types of actions, including habits like brought into play much earlier; it is an excellent me-

tooth brushing and infrequent voluntary activities like dium for experimenting with conceptual meanings

scheduling and taking a physical examination. More and relationships. Working papers can help research-

general terms may be sought for theoretical concepts ers explore their thoughts and reveal gaps, inconsis-

currently defined in a limited domain. More abstract tencies, and faulty reasoning (Flower, 198 l). In such

terms also may suggest other domains where the the- papers researchers should address questions such as

ory might be applied (Mills, 1959, pp. 212-213). For these: What is the core issue or question here? Why

example, the concept "social loss of dying patients" is it important? What key concepts are imbedded in

can be expanded to "the social value of people" this topic and how are they related? What alternative

(Glaser & Strauss, 1967). methods can be used to answer the central question?

Concept analysis, a procedure developed by phi- What types of answers are desirable and feasible? (cf.

losophers, can be used to clarify our thinking about Gowin, 1981a, pp. 86-107).

terms we use in research. The first step is to identify

cases or examples that clearly fit the intended meaning How to Begin

of the concept being analyzed. To illustrate, a clear

Researchers who wish to explore these techniques

example of my concept of job involvement might be

should choose several strategies that seem appropriate

working extra hours without pay when there is no

to their problem and then consult the cited references

external pressure to do so. Other examples--ones that

for further details on each strategy. Any strategy ex-

are deafly outside the intended meaning and others

plored should be given at least several hours of the

that are borderline--are then evoked. From a careful

researcher's "best t i m e " - - a period when he or she is

review of such cases, the researcher can draw out the

alert, relaxed, and free from distractions and inter-

essential properties of the concept as he or she uses

ruptions. Not every strategy attempted will prove

it. (Concept analysis is described and illustrated in

fruitful for a given person or problem.

Wilson, 1963, and in Gowin, 1981b, pp. 199-205.)

Devoting time to expanding and ordering one's

conceptual frame can seem like a frivolous diversion

Specify Relationships Among Concepts from more pressing tasks. Yet the potential payoffs

The most rigorous ways of expressing relationships are substantial. A single new insight can go a long

among concepts, such as mathematical modeling and way, particularly in specialties in which theoretical

October 1985 American Psychologist 1101

I

Figure 2

A Concept Map of Gowin's Theory of Educating

I Educating ]

eventful I which atpresupposes

process ~ m s ---

the p o s s i b i l i t y of

change [

which leads

tO a change

~ meaning of human I

] experience .... [ lithe

In the I

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

ie I educative

lindoctri=tien I isnciali--tieoJ Icendi"ooingI

I dellberate intervention

aimed at

shaping

, criteria of excellence a~%,

~'sped~ ing in /

~expounded Imantfeated ]gr guiding I felt atgnificance~

curriculuB governance

Note. From Educating (p. 94) by D. B. Gowin, 1981, Ithaca, NY: Comell University Press. Copyright 1981 by Comell University Press, Reprinted by

permission.

Campbell, D. T. (1974, September). Qualitative knowing in action

a n d m e t h o d o l o g i c a l t r a d i t i o n s are strong a n d i n w h i c h

research. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Psy-

m o s t p u b l i s h e d c o n t r i b u t i o n s are v a r i a t i o n s o n fa-

chological Association, New Orleans.

m i l i a r t h e m e s . P r o p e r l y developed, a fresh idea c a n

Campbell, J. P,, Daft, R. L., & Hulin, C. L. (1982). What tostudy:

have a l a s t i n g i m p a c t . Generating and developing research questions. Beverly Hills, CA:

Sage.

REFERENCES Caplan, N., & Nelson, S. D. (1973). On being useful: The nature

and consequences of psychological research on social problems.

Allison, G. T. (1971). Essence of decision. Boston: Little, Brown. American Psychologist, 28, 199-211.

Barker, R. G. (1963). On the nature of the environment. Journal Cohen, A. R. (1964). Attitude change and social influence. New

of Social Issues, 19(4), 17-38. York: Basic Books.

Barker, R. G. (1968). Ecologicalpsychology: Concepts and methods Cottam, K. M., & Pelion, R. W. (1977). Writer'sresearchhandbook.

for studying the environment of human behavior. Stanford, CA: New York: Barnes & Noble.

Stanford University Press. Cox, V. C., Paulus, P. B., & McCain, G. (1984). Prison crowding

Barrett, G. V., & Bass, B. M. (1976). Cross-cultural issues in in- research: The relevance for prison housing standards and a general

dustrial and organizational psychology. In M. D. Dunnette, (Ed.), approach regarding crowding phenomena. American Psychologist,

Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1639- 39, 1148-1160.

1686). Chicago: Rand-McNally. Crovitz, H. E (1970). Galton's walk. New York: Harper & Row.

Bart, P., & Frankel, L. (1981). The student sociologist's handbook Davis, M. S. (1971). That's interesting: Toward a phenomenolngy

(3rd ed.). Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman. of sociology and a sociology of phenomenology. Philosophy of

Brinberg, D., & MeGrath, J. E. (1985). Validity and the research the Social Sciences, 1, 309-314.

process. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Flower, L. (1981). Problem-solving strategiesfor writing. New York:

Brunswik, E. (1947). Systematic and representative design of psy- Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

chological experiments. Berkeley: University of California Press. Galton, E (1879). Psychometric experiments. Brain, 2, 148-162.

1102 O c t o b e r 1985 A m e r i c a n Psychologist

Georgoudi, M., & Rosnow, R. L. (1985). Notes toward a contex- McKim, R. H. (1972). Experiences in visual thinking. Monterey,

tualist understanding of social psychology. Personality and Social CA: Brooks/Cole.

Psychology Bulletin, 11, 5-22. M ilgram, S. (1970). The experience of living in cities. Science, 167,

Gergen, K. J. (1978). Toward generative theory. Journal of Person- 1461-1468.

ality and Social Psychology, 36, 1344-1360. Miller, J. G. ( 1971). Living systems: The group. BehavioralScience,

Gergen, K. J. (1982). Toward transformation in social knowledge, 16, 302-398.

New York: Springer.

Mills, C. W. (1959). The sociological imagination. New York: Oxford

Gergen, K, J., & Gergen, M. M. (Eds.). (1984). Historical social University Press.

psychology. Hillsdale, N J: Erlbaum.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A, L. (1967). The discovery of grounded Neisser, U. (1981). John Dean's memory: A case study. Cognition,

theory. Hawthorne, N ~ Aldine. 9, 1-22.

Giaser, R. (1984). Education and thinking: The role of knowledge. Nelms, N. (1981). Thinking with a pencil. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press.

American Psychologist, 39, 93-104. Petrinovich, L. (1979). Probabilistic functionalism: A conception

Gowin, D. B. (198 l a). Educating. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University of research method. American Psychologist, 34, 373-390.

Press. Piotrkowski, C. S. (1978). Work and the family system. New York:

Gowin, D. B. (198 lb). Philosophy. In N. L. Smith (Ed.), Metaphors Free Press.

for evaluation (pp. 181-209). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Rosenzweig, M. R. (1984). Experience, memory, and the brain.

Guttentag, M., & Secord, P. F. (1983). Too many women? The sex American Psychologist, 39, 365-376.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

ratio question. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Runkel, P. J., & McGrath, J. E. ( ! 972). Research on human behavior:

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

Heider, E (1983). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Hillsdale, A systematic guide to method. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Win-

NJ: Erlbaum. (Original work published 1958) ston.

Jones, R. A. (1983, December). Academic insularity and the failure Sampson, E. E. (1981). Cognitive psychology as ideology. American

to integrate social and clinical psychology. Society for the Ad- Psychologist, 36, 730-743.

vancement of Social Psychology Newsletter, pp. 10-13. Secord, P. E (1984). Love, misogyny, and feminism in selected his-

Kirmeyer, S. L. (1984). Observing the work of police dispatchers: torical periods. In K. J. Gergen & M. M. Gergen (Eds.), Historical

Work overload in service organizations. In S. Oskamp (Ed.), Ap- social psychology (pp. 259-280). Hillsdale, NJ: Eflbaum.

plied socialpsychology annual (Vol. 5, pp. 45-66). Beverly Hills, Segall, M. H., Campbell, D. T., & Herskovitz, M. J. (1966). The

CA: Sage. influence of culture on visual perception. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: Merrill.

University of Chicago Press. Smith, N. L. (1981). Metaphors for evaluation. In N. L. Smith

Lawson, R. B. (1984). The graduate curriculum. Science, 225, 675. (Ed.), Metaphors for evaluation (pp. 51-65). Beverly Hills, CA:

Leary, D. E. (1983, April). Psyche's muse: The role of metaphor in Sage.

psychology. Paper presented at the meeting of the Western Psy- Statistical abstract of the United States. (1985). Washington, DC:

chological Association, San Francisco. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Lofland, J. (1976). Doing social life: The qualitative study of human Stokols, D. (1982). Environmental psychology: A coming of age. In

interaction in natural settings. New York: Wiley. A. Kraut (Ed.), G. Stanley Hall lecture series (Vol. 2, pp. 155-

Mackie, R. R. (1974, August). Chuckholes in the bumpy road from 205). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

research to application. Paper presented at the meeting of the Tyler, L. E. (1983). Thinking creatively. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

American Psychological Association, New Orleans. Wachtel, P. L. (1980). Investigation and its discontents: Some con-

Malpass, R. S. (1977). Theory and method in cross-cultural psy- straints on progress in psychological research. American Psy-

chology. American Psychologist, 32, 1069-1079. chologist, 35, 399--408.

Manicas, P. T., & Secord, P. E (1983). Implications for psychology Webster's third new international dictionary of the English language,

of the new philosophy of science. American Psychologist, 38, 399- unabridged. (1969). Springfield, MA: Merriam.

413. Weick, K. E. (1968). Systematic observational methods. In G.

Maruyama, A. J. (1963). The second cybernetics: Deviation-am- Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook ofsocialpsychology

plifying mutual causal processes. American Scientist, 51, 164- (2nd ed., pp. 357-451). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

179. Weick, K. E. (1979). The social psychology of organizing (2nd ed.).

McGrath, J. E. (1968). A multifacet approach to classification of Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

individual, group, and organization concepts. In B. P. Indik & Wicker, A. W. (1969). Attitudes versus actions: The relationship of

E K. Berrien (Eds.), People, groups, and organizations (pp. 192- verbal and overt behavioral responses to attitude objects. Journal

215). New York: Teachers College Press. of Social Issues, 25(4), 41-78.

McGuire, W. J. (1964). Inducing resistance to persuasion. In L. Wicker, A. W. (1983). An introduction to ecological psychology. New

Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. York: Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1979)

l, pp. 192-229). New York: Academic Press. Wicker, A. W. (in press). Behavior settings reconsidered: Temporal

McGuire, W. J. (1973). The yin and yang of progress in social psy- stages, resources, internal dynamics, context. In D. Stokols & I.

chology: Seven koan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Altman (Eds.), Handbook ofenvironmentalpsychology. New York:

26, 446-456. Wiley.

McGuire, W. J. (in press). Toward psychology's second century. In Wilson, J. B. (1963). Thinking with concepts. Cambridge, England:

S. Koch & D. E. Leary (Eds.), A century of psychology as science. Cambridge University Press.

New York: McGraw-Hill. Young, R. E., Becker, A. L., & Pike, K. L. (1970). Rhetoric."Discovery

McKelvey, B. (1982). Organizational systematics. Berkeley: Uni- and change. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

versity of California Press. Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149, 269-274.

O c t o b e r 1985 A m e r i c a n P s y c h o l o g i s t 1 103

You might also like

- Kairos $53.581,40Document1 pageKairos $53.581,40Edwin GilNo ratings yet

- Kairos $53.581,40Document1 pageKairos $53.581,40Edwin GilNo ratings yet

- Kairos $22.429,91Document1 pageKairos $22.429,91Edwin GilNo ratings yet

- The Feeling Space.: Lauri Nummenmaa Et Al. PNAS 2018 115:37:9198-9203Document1 pageThe Feeling Space.: Lauri Nummenmaa Et Al. PNAS 2018 115:37:9198-9203Edwin GilNo ratings yet

- Rstudio IdeDocument1 pageRstudio IdeEdwin GilNo ratings yet

- DemostraciónMCO (Sumas&Matrices) MatrizInversaDocument8 pagesDemostraciónMCO (Sumas&Matrices) MatrizInversaEdwin GilNo ratings yet

- 510 Tangram Wolf Shape Puzzle Game PDFDocument1 page510 Tangram Wolf Shape Puzzle Game PDFEdwin GilNo ratings yet

- R Cheat Sheet 3 PDFDocument2 pagesR Cheat Sheet 3 PDFapakuniNo ratings yet

- The Feeling Space.: Lauri Nummenmaa Et Al. PNAS 2018 115:37:9198-9203Document1 pageThe Feeling Space.: Lauri Nummenmaa Et Al. PNAS 2018 115:37:9198-9203Edwin GilNo ratings yet

- Stringr R PackageDocument2 pagesStringr R PackageMiguel HinojosaNo ratings yet

- Rstudio IdeDocument2 pagesRstudio IdeLuis CastilloNo ratings yet

- Krugman/Wells, ECONOMICS: The Organization of This Book and How To Use ItDocument5 pagesKrugman/Wells, ECONOMICS: The Organization of This Book and How To Use ItEdwin GilNo ratings yet

- The Commanding Heights: Battle for World EconomyDocument7 pagesThe Commanding Heights: Battle for World EconomyEdwin GilNo ratings yet

- Participant Observation: Danny LjorgensenDocument21 pagesParticipant Observation: Danny LjorgensenEdwin GilNo ratings yet

- Games, Strategies and Decision MakingDocument1 pageGames, Strategies and Decision MakingEdwin Gil0% (2)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Fundamentals of Mathematics PDFDocument724 pagesFundamentals of Mathematics PDFalphamalie50% (2)

- Engineering Leadership SkillsDocument9 pagesEngineering Leadership Skillsasoooomi_11No ratings yet

- AI Brochure PDFDocument2 pagesAI Brochure PDFCuszy MusNo ratings yet

- Midterm Exam in OCDocument4 pagesMidterm Exam in OCCarla CacharoNo ratings yet

- Employee Attitude SurveyDocument5 pagesEmployee Attitude SurveyCleofyjenn Cruiz QuibanNo ratings yet

- The Situation of Hawaiian and Hawai'i Creole English - A Language Rights Perspective On Language in Hawai IDocument11 pagesThe Situation of Hawaiian and Hawai'i Creole English - A Language Rights Perspective On Language in Hawai IDaniel OesterleNo ratings yet

- A1 Russian CourseDocument64 pagesA1 Russian CourseRachid RachidNo ratings yet

- Languages 2011Document26 pagesLanguages 2011redultraNo ratings yet

- GMR Stint Review FormDocument2 pagesGMR Stint Review FormRoshan SinghNo ratings yet

- Moneyball Seminario 2Document33 pagesMoneyball Seminario 2robrey05pr100% (1)

- The Resilience ToolkitDocument28 pagesThe Resilience ToolkitArran KennedyNo ratings yet

- Jan de Vos - The Metamorphoses of The Brain - Neurologisation and Its DiscontentsDocument256 pagesJan de Vos - The Metamorphoses of The Brain - Neurologisation and Its DiscontentsMariana RivasNo ratings yet

- Psychology (037) Class-XII Sample Question Paper Term II 2021-2022 Time - 2 Hours Max Marks - 35 General InstructionsDocument3 pagesPsychology (037) Class-XII Sample Question Paper Term II 2021-2022 Time - 2 Hours Max Marks - 35 General InstructionspushkarNo ratings yet

- Book - 1980 - Bil Tierney - Dynamics of Aspect AnalysisDocument172 pagesBook - 1980 - Bil Tierney - Dynamics of Aspect Analysispitchumani100% (12)

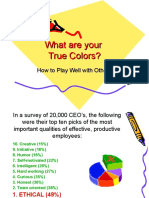

- What Are Your True Colors?Document24 pagesWhat Are Your True Colors?Kety Rosa MendozaNo ratings yet

- SchopenhauerDocument7 pagesSchopenhauerdanielNo ratings yet

- Management Consultancy SummaryDocument2 pagesManagement Consultancy Summaryeljay lumboNo ratings yet

- Exercise For SQ3RDocument6 pagesExercise For SQ3RNajmi TajudinNo ratings yet

- BCPE Sample Questions Answers Jul141Document10 pagesBCPE Sample Questions Answers Jul141ProfessorTextechNo ratings yet

- CRE - Dari From EnglishDocument54 pagesCRE - Dari From EnglishTarlan TarlanNo ratings yet

- Task Analysis: Story Boarding - HTADocument19 pagesTask Analysis: Story Boarding - HTANeeleshNo ratings yet

- VERBS Elliptical ConstructionDocument4 pagesVERBS Elliptical ConstructionCanduNo ratings yet

- Afl Rubric IctDocument2 pagesAfl Rubric Ictapi-281630556No ratings yet

- INT WS GR 08-09 Intermediate W01 - ONL TeacherDocument8 pagesINT WS GR 08-09 Intermediate W01 - ONL Teacherandreia silverioNo ratings yet

- 1861 1400809984Document9 pages1861 14008099842read0% (1)

- Data Analytics For Accounting Exercise Multiple Choice and Discussion QuestionDocument3 pagesData Analytics For Accounting Exercise Multiple Choice and Discussion Questionukandi rukmanaNo ratings yet

- Peplau - Interpersonal Relations Theory - NursingDocument39 pagesPeplau - Interpersonal Relations Theory - NursingAnn M. Hinnen Sparks100% (11)

- Scatter Plot Lesson PlanDocument8 pagesScatter Plot Lesson Planapi-254064000No ratings yet

- WJ - I Insights Discovery An Introduction Journal v1 2010 Spreads (Not For Printing) PDFDocument30 pagesWJ - I Insights Discovery An Introduction Journal v1 2010 Spreads (Not For Printing) PDFAna Todorova100% (1)

- The Introvert AdvantageDocument28 pagesThe Introvert Advantagequeue201067% (3)