Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Booth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. 358pp

Uploaded by

JamesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Booth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. 358pp

Uploaded by

JamesCopyright:

Available Formats

ISEAS DOCUMENT DELIVERY SERVICE.

No reproduction without permission of the

publisher: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace, SINGAPORE

119614. FAX: (65)7756259; TEL: (65) 8702447; E-MAIL: publish@iseas.edu.sg

Book Reviews 417

Statecraft and Security: The Cold War and Beyond. Edited by Ken

Booth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. 358pp.

This book, written from a liberal perspective of international relations,

seeks to identify a way out of the Cold War logic of structural conflict

and to identify new developments and trends affecting inter-state

relations which necessitate increased co-operation. While statecraft

still defines the agendas and conduct of the business of global politics,

the decisions of policy-makers are influenced by a multitude of factors

which require a notion of security much broader than that which

prevailed during the Cold War.

Consequently, Part I, of three parts, examines the history of the Cold

War with a critical eye in order to distill the lessons of this period. Ned

Lebow and Janice Stein expose the fallacy of nuclear security. The

capitalist West (the United States) may have won the Cold War but at

what cost? Did the world not come close to destruction of humanity on

many occasions? Ken Booths Cold Wars of the Mind examines the

different meanings of the Cold War and urges us not to forget the real

Cold War. Amid Western gloating over its victory, Booth finds

a profound unwillingness to remember and internalize the

potential costs of superpower Armageddon nuclear amnesia. If we

live simultaneously in the past, present and future, then these lessons

must be internalized and become part of an honest history. Such a

history might reveal Raymond Garthoffs contention that the start of the

Cold War was not the result of structural confrontation between powers

in an anarchical world, and the end, as a result of internal collapse,

came in spite of Western pressure and not because of it.

Opportunities for co-operation were perhaps missed by the

superpowers based on a misreading (contrived or not) of each others

intentions.

The resulting nuclear deterrence theory is the object of criticism

through an analysis of A Cold War Life, that of Michael McGwire, an

analyst of the Soviet Union whose career spanned the British

intelligence service, academia, and Washington policy-circles. He

consistently argues for a realistic assessment of Soviet politics,

intentions, and capabilities. The pursuit of nuclear deterrence, then and

now, is a chimera since it cannot be stable with two superpowers, let

alone multiple players. A world of several active nuclear players is one

in which a nuclear attack somewhere, at some time, is virtually assured.

Those who formulated the theory had very little knowledge of the

Soviets. Theoretical explanations should be based on sound empirical

analysis, rather than the other way round facts should not be made to

fit theory. A honeymoon period at the end of the Cold War offers the

chance to break away from Cold War deterrence thinking.

2000 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore

418 Book Reviews

However, the remaining superpower, the United States, has not yet

demonstrated the kind of leadership necessary to transform the

international political structure, according to John Steinbrunner in Part

II, which examines powers the United States, Russia, Europe, Japan,

China, and middle powers and their policies. For him, the United

States is stuck in the Cold War mode in terms of military posture and

ways of thinking about the world. Two changes in particular

information technology and unprecedented growth in world

population require novel thinking about the international system to

solve problems such as unemployment. Wealth will have to be shared

more equitably to avoid civil disorders, one of the most pressing

problems. The United States seems not to have the will nor the stomach

to intervene in every case of internal disintegration.

The problem of disintegration is most evident in Russia, which is

the object of much discussion in this section. Chapters by Oles

Smolansky and Karen Dawisha analyse Russia over a longer historical

period. For the former, the seeds of a new political system have been

planted in Russia which will help it to escape from its past. The old

Russia authoritarian, under the sway of the Orthodox church,

the secret police, the bureaucracy, corruption, and nationalism

was not destroyed in 1917, but there is unlikely to be a return to

authoritarianism. In matters of foreign policy, both authors point to the

legitimate security interests in Russias perceived sphere of influence,

the near abroad the newly independent states which were once

part of the Soviet empire. For Dawisha, the will for traditional

imperialism (the quest for territory) is not evident, but Russia will

dominate this Eurasian space for security and economic reasons. The

challenge for the states of the near abroad is to foster economic

interdependence with Russia to avoid autocolonization.

Such interdependence continues unabated in Europe, which defies

neo-realist doom-and-gloom predictions of fracture. Europe has not

descended into power politics but continues to experiment with deeper

integration. Neo-realists erroneously assumed that European Union

(EU) unity was a product of the Cold War (rather, it was a cure for

Franco-German rivalry), that the United States will abandon the

European continent (it remains despite domestic opposition) and that

Western European governments will revert to balance of power policies.

While the EU is not yet a complete international actor, Robert ONeill

notes that it has international concerns the development of

international law, the control of weapons of mass destruction, and the

promotion of human rights and democracy.

Co-operation seems to be the hallmark of East Asian international

politics and, in particular, as Geoffrey Hawthorne notes, of Japanese

2000 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore

Book Reviews 419

foreign policy. What matters most to a Japan constrained by consensus

decision-making is economic success, for which co-operation is

necessary. But Japan, like the rest of East Asia, will no longer show the

same deference to the West as relations converge on a more equal

footing. China is the power most capable of challenging American

hegemony in the international system in the future. But does it mean

that a new Cold War will emerge? Michael Coxs answer is no.

Following McGwires example, he calls for a realistic assessment of

Chinese intentions and capabilities. Worst case scenarios may be

exaggerated in the light of the following: the existing power projection

capabilities of China are inadequate, its leaders have embraced

elements of capitalism, it is engaged in multilateral security co-

operation in the Asia-Pacific, it is keen to join the World Trade

Organization, and the United States is keen to tap Chinas markets.

The United Nations comes more into focus in the final chapter of

Part II. Denis Stair examines the ambiguous concept of middle powers

(such as the Netherlands, Belgium, Ireland, Poland, India, Canada,

Australia, and the Scandinavian countries), which by necessity must

rely much more on collective means to achieve security and other goals.

One possibility for a more effective contribution to international peace

and security is that they could act constructively together in preparing

for international peacekeeping and peacebuilding operations of the

United Nations, as the demand for its services seems to be increasing.

The liberal bias and the need to rethink Cold War concepts of

security comes out clearly in the final section. International peace and

security in the twenty-first century demands a reformed and revitalized

United Nations, according to Barry Blechman in his opening chapter of

Part III (Resistances and Reinventions). Economic interdependence,

technology diffusion, global audience, and supposed emerging shared

values are leading to a structure of international politics far different

from that which characterized the twentieth century. For Blechman,

there is an accelerating tendency for countries to work together on

international problems, and the United Nations is seen as the most

effective instrument to co-ordinate efforts at dealing with global

problems and to counter the hegemonic aspirations of powers.

Anthony Giddens discussion of a post-scarcity society creates a

bridge between the international and domestic dimensions. More

specifically, he shows how this influences our everyday lives and the

choices we make. He introduces the notion of lifestyle bargaining,

which involves the establishing of trade-offs or resources, based upon

life-political coalitions between different groups. For Giddens, we

always have possibilities of individual and collective choice this is

the very core of life politics . We can try to use whatever choices we

2000 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore

420 Book Reviews

have in a fruitful way. Choice is also the core theme of Philip Alotts

penultimate chapter. He examines the myth of the concept of human

nature, which requires us to believe in a second self which is a

universal self, or an instinctive self. Since we are constantly creating

the past as we make the future, the latter need not be held prisoner to

the myth of an unchanging human nature. We are what we choose to

be. In conclusion to this wide-ranging book, Ken Booth discusses three

crucial aspects of global transformation globalization, global

governance, and global moral science. The last asks whether dominant

ideas of the past are sufficient to answer questions for the future.

A minor critique of this work is the exclusion of India and Latin

America, or one of its major constituents. Collectively and individually,

these countries are having an impact on the international system, which

is not negligible. While UNICEFs Geoffrey Hawthorne rightly points to

the need for a more collaborative spirit in helping Africa to face many

challenges, which cannot be ignored, its inclusion in a discussion of

powers and policies is incongruous.

Overall, this work should be required reading for students and

theorists of international relations. Its multi-disciplinary approach and

the inclusion of the policy-makers perspective into the overall analysis

makes for a more holistic analysis of the increasing complexities of

international relations. The attempt to incorporate the everyday lives of

people into the broader picture of global events is an endearing quality

of this book.

ROBIN RAMCHARAN

Jawaharlal Nehru University

New Delhi

Indonesian Politics in Crisis: The Long Fall of Suharto, 1996-98. By

Stefan Eklf. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies, 1999.

272pp.

When Soeharto abruptly resigned from the presidential office and

passed the sceptre to B. J. Habibie on the morning of 21 May 1998, even

Soehartos harshest critics were a little stunned that the tenacious old

man had finally given up. Stefan Eklf explains what happened in the

long run-up to that fateful morning. From intra-lite machinations in

the military and the regime to angry but unco-ordinated students, to

2000 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore

You might also like

- Realism Remains Dominating IR TheoryDocument11 pagesRealism Remains Dominating IR TheoryDee OanNo ratings yet

- Traditional and Modern Approaches To International LawDocument18 pagesTraditional and Modern Approaches To International LawAshish K Singh100% (1)

- Hist-1 2Document2 pagesHist-1 2Juan HuiracochaNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography - FinalDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliography - Finalmmehdi2No ratings yet

- Deciding To Intervene. The Reagan Doctrine and American Foreign PolicyDocument349 pagesDeciding To Intervene. The Reagan Doctrine and American Foreign PolicyIolanda Ulmeteanu100% (1)

- NATO Expansion A Realist S ViewDocument18 pagesNATO Expansion A Realist S ViewJNo ratings yet

- Download Russia China And The West In The Post Cold War Era The Limits Of Liberal Universalism Suzanne Loftus all chapterDocument67 pagesDownload Russia China And The West In The Post Cold War Era The Limits Of Liberal Universalism Suzanne Loftus all chapterkate.brown975100% (2)

- Thesis Chapter IDocument15 pagesThesis Chapter IMatthew Hanzel100% (1)

- The Role of Individuals in International Politics: A Psychological ApproachDocument19 pagesThe Role of Individuals in International Politics: A Psychological ApproachAsad MehmoodNo ratings yet

- MIT CIS Audit Examines Differences Between War on Terror and Cold WarDocument4 pagesMIT CIS Audit Examines Differences Between War on Terror and Cold WarVítor VieiraNo ratings yet

- Soft Power in The Roman Empire A Reassessment of CDocument12 pagesSoft Power in The Roman Empire A Reassessment of CKelli RudolphNo ratings yet

- 91 61YaleLJ1244 1952Document4 pages91 61YaleLJ1244 1952Abdullah AlzabediNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement of Cold WarDocument6 pagesThesis Statement of Cold Warwendyrobertsonphoenix100% (2)

- The Nature & Sources of Liberal International Order (Deudney & Ickenberry)Document19 pagesThe Nature & Sources of Liberal International Order (Deudney & Ickenberry)Rachel Dbbs100% (1)

- From Cold War To Hot Peace by Slavoj Žižek - Project SyndicateDocument9 pagesFrom Cold War To Hot Peace by Slavoj Žižek - Project SyndicatecamiclavNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Cold War Through The Lens of International TheoriesDocument6 pagesAnalyzing The Cold War Through The Lens of International TheoriesHasan ShohagNo ratings yet

- Essay (12th May) - Is There A New Cold War Between The US and China - (31987621)Document10 pagesEssay (12th May) - Is There A New Cold War Between The US and China - (31987621)Thomas FordreyNo ratings yet

- The New World Order in The Twenty-First CenturyDocument11 pagesThe New World Order in The Twenty-First CenturyIsais NNo ratings yet

- If Not Civilizations What - HuntingtonDocument10 pagesIf Not Civilizations What - HuntingtonDaniela Guzmán MonsalveNo ratings yet

- Nye, J (2022) - US & ChinaDocument17 pagesNye, J (2022) - US & ChinaThu Lan VuNo ratings yet

- JOSEPH NYE - How Not To Deal With A Rising ChinaDocument17 pagesJOSEPH NYE - How Not To Deal With A Rising ChinaDanilo R. SousaNo ratings yet

- Poy 002Document43 pagesPoy 002guessoumiNo ratings yet

- SORENSEN. G. An Analysis of The Contemporary Statehood.Document17 pagesSORENSEN. G. An Analysis of The Contemporary Statehood.Vitor FreireNo ratings yet

- One World Rival TheoriesDocument10 pagesOne World Rival TheoriesFran Salas GattiNo ratings yet

- Robert Jervis - Unipolarity. A Structural Perspective (2009)Document27 pagesRobert Jervis - Unipolarity. A Structural Perspective (2009)Fer VdcNo ratings yet

- NATO Expansion: A Realist's ViewDocument18 pagesNATO Expansion: A Realist's ViewFilippos Deyteraios100% (2)

- One World Many Theories PDFDocument17 pagesOne World Many Theories PDFEva Alam Nejuko ChanNo ratings yet

- 2021 China Rising Threat' or Rising Peace'Document17 pages2021 China Rising Threat' or Rising Peace'Shoaib AhmedNo ratings yet

- BB42Document23 pagesBB42madz224No ratings yet

- Book Rep 2 Lyle Goldstein Meeting China HalfwayDocument9 pagesBook Rep 2 Lyle Goldstein Meeting China HalfwayKateryna BidulaNo ratings yet

- Download A World Safe For Commerce American Foreign Policy From The Revolution To The Rise Of China Dale C Copeland full chapter pdf scribdDocument67 pagesDownload A World Safe For Commerce American Foreign Policy From The Revolution To The Rise Of China Dale C Copeland full chapter pdf scribdhazel.farley831100% (2)

- Cold War Research Paper ThesisDocument6 pagesCold War Research Paper Thesisc9rbzcr0100% (1)

- Required Pre Course ReadingsDocument4 pagesRequired Pre Course ReadingsNelu PolituNo ratings yet

- The Cold War - What Do We Now KnowDocument25 pagesThe Cold War - What Do We Now KnowHimaniNo ratings yet

- Thesis Cold War EssayDocument4 pagesThesis Cold War Essaypkznbbifg100% (2)

- KRAMER, M. (1999) - Ideology and The Cold War. Review of International Studies, 25 (4), 539-576Document38 pagesKRAMER, M. (1999) - Ideology and The Cold War. Review of International Studies, 25 (4), 539-576OANo ratings yet

- IR Theory and The Third WorldDocument12 pagesIR Theory and The Third WorldJames FaganNo ratings yet

- Clash of GlobalizationsDocument7 pagesClash of GlobalizationsSantino ArrosioNo ratings yet

- Realism 1Document43 pagesRealism 1Dilanga LankathilakaNo ratings yet

- 1 - Stephen M Walt - One World Many TheoriesDocument11 pages1 - Stephen M Walt - One World Many Theoriesmariu2No ratings yet

- 5ee34f9c40967 PDFDocument14 pages5ee34f9c40967 PDFFaizullahMagsiNo ratings yet

- Russia China and The West in The Post Cold War Era The Limits of Liberal Universalism 3031200888 9783031200885 CompressDocument187 pagesRussia China and The West in The Post Cold War Era The Limits of Liberal Universalism 3031200888 9783031200885 Compresshemid92No ratings yet

- The Clash of CivilizationsDocument21 pagesThe Clash of CivilizationsmsohooNo ratings yet

- Counter Hegemonic Strategies in The Global EconomyDocument28 pagesCounter Hegemonic Strategies in The Global EconomyphbergantinNo ratings yet

- Nye (1988) Neorealism and NeoliberalismDocument18 pagesNye (1988) Neorealism and NeoliberalismVinícius JanickNo ratings yet

- Asymmetry Theory and China's Concept of Multipolarity: Brantly WomackDocument16 pagesAsymmetry Theory and China's Concept of Multipolarity: Brantly WomackPaolo MendioroNo ratings yet

- Johnson Brian Realism ConstructivismDocument33 pagesJohnson Brian Realism ConstructivismMuhammad Ali SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- FA - The Long Unipolar Moment. Debating American Dominance - Foreign AffairsDocument13 pagesFA - The Long Unipolar Moment. Debating American Dominance - Foreign AffairsAlex García CastrillónNo ratings yet

- Foreign Policy for America in the Twenty-first Century: Alternative PerspectivesFrom EverandForeign Policy for America in the Twenty-first Century: Alternative PerspectivesNo ratings yet

- Escaping the Deadly Embrace: How Encirclement Causes Major WarsFrom EverandEscaping the Deadly Embrace: How Encirclement Causes Major WarsNo ratings yet

- Critical Review Susan Strange 1994 AbstrDocument9 pagesCritical Review Susan Strange 1994 AbstrLuanBelomoNo ratings yet

- The Causes of War Syllabus - Jack LevyDocument13 pagesThe Causes of War Syllabus - Jack LevySergio CatignaniNo ratings yet

- If Not Civilizations, What, Samuel Hunting TonDocument7 pagesIf Not Civilizations, What, Samuel Hunting TonAlain ZhuNo ratings yet

- A New Cold War? M. Doyle.Document12 pagesA New Cold War? M. Doyle.lucilalestrangewNo ratings yet

- Normative Structures in IPDocument8 pagesNormative Structures in IPAmina FELLAHNo ratings yet

- Revew of Great Powers and Geopolitical Change by JDocument6 pagesRevew of Great Powers and Geopolitical Change by JJau HameedNo ratings yet

- Draft Intro To IrDocument3 pagesDraft Intro To IrBellaloNo ratings yet

- Ir 05Document3 pagesIr 05warnakulasooriyaNo ratings yet

- 128 BSanket Jamuar VInternational RelationDocument15 pages128 BSanket Jamuar VInternational Relationyash anandNo ratings yet

- Clase 1 - KahlerDocument39 pagesClase 1 - KahlerLucas LarseNo ratings yet

- Realism's Primacy of Foreign Policy ChallengedDocument23 pagesRealism's Primacy of Foreign Policy ChallengedJoão GoulartNo ratings yet

- The End of Cold War. A Short Introduction To The Theory of Post Cold - War EraDocument7 pagesThe End of Cold War. A Short Introduction To The Theory of Post Cold - War EraAndreas TzanavarisNo ratings yet

- What Makes a Country Run: Characteristics of an Effective StateDocument3 pagesWhat Makes a Country Run: Characteristics of an Effective StatebagumaNo ratings yet

- Introduction to International Organizations Course OverviewDocument2 pagesIntroduction to International Organizations Course OverviewJs SoNo ratings yet

- The League of NationsDocument13 pagesThe League of Nationskrischari100% (2)

- The Vision of Anglo-AmericaDocument240 pagesThe Vision of Anglo-AmericaStefan BoldisorNo ratings yet

- The Importance of The United Nations OrganizationDocument2 pagesThe Importance of The United Nations OrganizationGeorge Valentin Popescu100% (1)

- PAK America RelationsDocument5 pagesPAK America RelationsHammadZenNo ratings yet

- Relevance of Vienna ConventionDocument27 pagesRelevance of Vienna ConventionIsabelleVladoiu100% (1)

- Neoclassical RealismDocument8 pagesNeoclassical RealismDianaDeeNo ratings yet

- Berlin Wall Annotated BibliographyDocument2 pagesBerlin Wall Annotated Bibliographyclaytoncaple100% (2)

- How To Run The WorldDocument6 pagesHow To Run The Worldlaiba israrNo ratings yet

- Failure of United Nations PDFDocument2 pagesFailure of United Nations PDFNick0% (1)

- Structure and Function of The United NationsDocument2 pagesStructure and Function of The United NationsDavid WNo ratings yet

- Morse Jessica ResumeDocument2 pagesMorse Jessica ResumeJessica Morse100% (2)

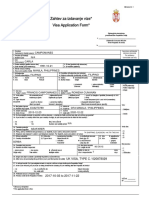

- Visaform Lat SerbiaDocument2 pagesVisaform Lat SerbiaFoamex Serbia100% (1)

- International Relations P2 – Past Papers Analysis (CSS 2016-2020) PDFDocument4 pagesInternational Relations P2 – Past Papers Analysis (CSS 2016-2020) PDFShahzeb Bin TariqNo ratings yet

- Economic DiplomacyDocument10 pagesEconomic DiplomacyGeorgianaIonelaNo ratings yet

- Philippines' Archipelagic Baselines Law UpheldDocument2 pagesPhilippines' Archipelagic Baselines Law UpheldMeng GoblasNo ratings yet

- Position Paper: - Republic of CubaDocument2 pagesPosition Paper: - Republic of CubaYeh YehNo ratings yet

- Forum: Topic: Main Submitter: Co-Submitters: Deeply ConcernedDocument6 pagesForum: Topic: Main Submitter: Co-Submitters: Deeply ConcernedPROVEZORNo ratings yet

- The Success of The Shanghai FiveDocument11 pagesThe Success of The Shanghai FiveNabilaFatmaGiyantiNo ratings yet

- Beyond American Hegemony: The Future of The Western AllianceDocument298 pagesBeyond American Hegemony: The Future of The Western AllianceTCFdotorg100% (1)

- 09 Arab LeagueDocument2 pages09 Arab LeagueMy BusinessNo ratings yet

- Accession of The Princely StatesDocument5 pagesAccession of The Princely StatesTaha Yousaf0% (1)

- Un Veto Citit - PDFTDocument35 pagesUn Veto Citit - PDFTHani ChkessNo ratings yet

- PM Letter To EU Council PresidentDocument6 pagesPM Letter To EU Council PresidentThe Guardian93% (14)

- Army+++++++2 Rising Star China 039 S New Security DiplomacyDocument281 pagesArmy+++++++2 Rising Star China 039 S New Security DiplomacyIoana MorosanuNo ratings yet