Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Warm Demander Article

Uploaded by

api-302779030Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Warm Demander Article

Uploaded by

api-302779030Copyright:

Available Formats

Leadership for Change

September 2008 | Volume 66 | Number 1

The Positive Classroom Pages 54-58

The Teacher as Warm Demander

Elizabeth Bondy and Dorene D. Ross

How can you create an engaging classroom? Convince students

first that you careand then that you'll never let up.

Consider this comment that a beginning teacher in an urban school recently

made to us:

They are calling one another names and being really catty, and it wears me out. I

mean, as soon as they walk in the door, someone is pushing or calling

someone a name. So it's 8:00 in the morning, and I am already flustered.

Many teachers in high-poverty schools struggle to establish a positive classroom

environment. These teachers know a great deal about their students, feel

affection for them, and empathize with their struggles. Unfortunately, the way

these teachers act on their caring is often not comprehensive enough to make a

difference. The teachers work hard to design interesting lessons, but if students

are disengaged, the quality of the lessons will be irrelevant and misbehavior will

reveal students' underlying resistance.

What is missing is not skill in lesson planning, but a teacher stance that

communicates both warmth and a nonnegotiable demand for student effort and

mutual respect. This stanceoften called the warm demanderis central to

sustaining academic engagement in high-poverty schools.

The stakes are high when it comes to engagement. Studies have amply

demonstrated a link between achievement and academic engagement, defined by

Furrer and Skinner (2003) as "active, goal-directed, flexible, constructive,

persistent, and focused interactions" with academic tasks (p. 149). The

consequences of disengagement are more serious for low-income students:

When students from advantaged backgrounds become disengaged, they may

learn less than they could, but they usually get by or they get second chances.

In contrast, when students in high-poverty, urban high schools become

disengaged, they are less likely to graduate and consequently face severely limited

opportunities [including] unemployment, poverty, poor health, and

EDEquity, Inc. All Rights Reserved

Leadership for Change

involvement in the criminal justice system. (National Research

Council, 2004, p. 1)

The good news is that although engagement is affected by students'

economic and social conditions, teachers can organize the classroom in ways that

dramatically increase student engagement.

What Is a Warm Demander?

Kleinfeld (1975) coined the phrase warm demander to describe the type of teacher

who was effective in teaching Athabaskan Indian and Eskimo 9th graders in

Alaskan schools. These teachers communicated personal warmth and used an

instructional style Kleinfeld called "active demandingness." They insisted that

students perform to a high level. Irvine and Fraser (1998) provide an example of

how a teacher using this style might speak to a student who is slacking off:

That's enough of your nonsense, Darius. Your story does not make sense. I told

you time and time again that you must stick to the theme I gave you. Now sit

down. (p. 56)

This kind of communication is seldom described in the effective-teaching

literature. Scholars who have investigated the warm demander stance have

concluded that it is often an effective teaching style with many students,

although it may appear harsh to the uninformed observer (Bondy, Ross,

Gallingane, & Hambacher, 2007; Irvine & Fraser, 1998; Ware, 2006). Let's look at

what makes this approach effective and how more teachers might adopt it.

Becoming a Warm Demander

Becoming a warm demander begins with establishing a caring relationship that

convinces students that you believe in them. The saying goes, "It's not what you

say that matters; it's how you say it." In acting as a warm demander, "how you

say it" matters, but who you are and what students believe about your intentions

matter more. When students know that you believe in them, they will interpret

even harsh-sounding comments as statements of care from someone with their

best interests at heart. As one student commented, "She's mean out of the

kindness of her heart" (Wilson & Corbett, 2001, p. 91).

This quote, pulled from interviews with 200 students in high-poverty middle

schools in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, highlights the second part of being a warm

demander. Warm demanders care enough to relentlessly insist on two things:

that students treat the teacher and one another respectfully and that they

complete the academic tasks necessary for successful futures. These teachers

adopt what Wilson and Corbett (2001) call a "no excuses" philosophy.

EDEquity, Inc. All Rights Reserved

Leadership for Change

Warm demanders approach students, particularly those whose

behavior causes trouble in the classroom, with unconditional

positive regard, a genuine caring in spite of what that student might

do or say (Rogers, 1957). At the heart of unconditional positive regard is a belief

in the individual's capacity to succeed. Teachers convey such an attitude by

taking the following three actions.

Build Relationships Deliberately

Middle school students interviewed by Cushman and Rogers (2008) explained

that they wanted teachers to "show us that you like us and find us interesting"

(p. 65). One tactic is to give students "getting-to-know-you" questionnaires (see

Cushman & Rogers, 2008, for examples), but such questionnaires will only work

if students perceive that you are genuinely interested and if you subsequently use

the information you gather.

Day-to-day interactions are more important than formal questionnaires. A smile,

a hand on the shoulder, the use of a student's name, or a question that shows

you remember something the student has mentionedthese small gestures do

much to develop relationships. Don't underestimate their power.

Learn About Students' Cultures

Use your knowledge of culture and learning styles to increase your understanding

of individual students. Warm demanders observe students closely to learn more

about their idiosyncrasies, interests, experiences, and talents. They watch for

clues to learning-style preferences: Does she work well independently? Does he

need visual cues to process what he hears? These teachers become students of

their students' cultures, learning about the music they listen to, the television

shows they watch, and their after-school activities.

Warm demanders also recognize that their own cultural backgrounds guide their

values, beliefs, and behaviors. Although it can be difficult to perceive one's own

culture, culture consistently shapes an individual's behavior and reactions to the

behavior of others. Gaining insight into cultural values and habits helps teachers

monitor their reactions to student behaviors that they might deem "bad," but that

are considered normal or even valued in the student's home culture. Without

such reflection, a teacher's implicit assumptions can inadvertently communicate

to students a lack of caring.

For example, an Egyptian man told us how a teacher punished his elementary-

age son for pushing a classmate. When the man and his wife spoke with this

teacher, they realized that playful pushing is not accepted in U.S. culture; in

Egypt, it is an acceptable way for boys to communicate affection. Two aspects of

this teacher's approach could have harmed the teacher-student relationship.

First, she failed to ask either the boy or his parents why he had pushed another

EDEquity, Inc. All Rights Reserved

Leadership for Change

boy. Second, she assumed that this student knewand had chosen

to disobeyher behavioral standards. Therefore, her first response

was to punish him. Although this teacher is warm and friendly, her

lack of deep knowledge of her student or his culture prevented her from

conveying to him that she cared.

To gain cultural knowledge and competence, Ross, Kamman, and Coady (2007)

recommend that teachers

Learn about their own cultural beliefs and how those beliefs influence their

interactions with students and families.

Become curious about culture and difference; try to imagine how school

experiences might feel different to different groups (such as males and females

or native speakers and English language learners).

Study examples of successful students whose backgrounds differ from the

norm (see Corwin, 2001, or Esquith, 2004).

Question their reactions to students' behavior to identify potential cultural

misunderstandings.

Monitor the tendency to judge differences as abnormal.

Communicate an Expectation of Success

In our recent study of three novice teachers of black elementary students, we

watched teachers attempting to communicate this message on the first day of

school (Bondy et al., 2007). The 3rd grade teacher read a story about the

inevitability of mistakes and the importance of persistence. She shared her own

experience with failure and her philosophy of optimism and perseverance. The

5th grade teacher repeatedly made encouraging comments such as, "How easy

was that?"

A student Cushman (2003) interviewed summarized how teachers can create a

culture of success:

Remind us often you expect our best, encourage our efforts even if we are having

trouble, give helpful feedback and expect us to review don't compare us to

other students, and stick with us. (pp. 6467)

Beyond Believing to Insisting

Many teachers use motivational strategies such as these and believe that they

have high expectations. What makes warm demanders different is that they insist

on students meeting those expectations. They establish supports to ensure that

students will learn, and they communicate clearly to students that showing

respect to the teacher and to classmates is nonnegotiable. The following

strategies help teachers become successful demanders.

EDEquity, Inc. All Rights Reserved

Leadership for Change

Provide Learning Supports

The students Wilson and Corbett (2001) interviewed were clear that

the teachers who helped them most never gave up; they provided a

variety of activities to help different kinds of learners and taught until the light

bulb went on for every student. These students preferred teachers who explained

material thoroughly and in multiple ways; outlined steps for getting to an answer

("They do it step-by-step and they break it down"); moved to new material when

they believed students were ready rather than according to an arbitrary

timetable; and emphasized multiple ways of approaching a problem.

Support Positive Behavior

Although warm demanders may become frustrated by student behavior, they

accept problems as normal, and they believe in students' ability to improve. When

the effective novice teachers we observed confronted recurring behavior issues,

they collected data to help them understand the situation before taking action

(Bondy et al., 2007). These teachers approached problems reflectively, asking

such questions as, What factors might influence this problem? or When does this

behavior occur? They searched for solutions rather than blaming students or

dismissing their concerns.

Warm demanders reach out to students for help in understanding behavior

problems, which many well-intentioned teachers neglect to do. For example,

when Ravet (2007) asked 10 highly disengaged students why they had

disengaged, most of them explained that they were bored with the curriculum.

When Ravet asked these students' teachers the same question, teachers blamed

perceived deficits in students' attitude, ability, personality, and family

background. If instead of blaming, these teachers had respectfully listened to

students, they would have gained insight into how to intervene.

Be Clear and Consistent with Expectations

Warm demanders must "provide a tough-minded, no-nonsense, structured and

disciplined classroom environment" (Irvine & Fraser, 1998, p. 56). In our study of

effective teachers, we found that teachers used two main strategies to hold

student behavior to a high standard. First, teachers respectfully but insistently

repeated their requests and reminded students of their expectations. If students

did not comply, teachers calmly delivered consequences. We concluded that

the teachers' assertive communication style, combined with their strategies for

insisting that students follow through, created a climate in which teachers were

taken seriously. Although teachers were warm and often funny, there was no

question that they meant what they said. (Bondy et al., p. 344)

EDEquity, Inc. All Rights Reserved

Leadership for Change

Charney (2002) discussed ways to convey expectations to students

clearly: Keep demands simple and short; dignify your words with

actions; remind students only twice (the third time, "you're out"); tell

students what the "nonnegotiables" are; and use words that invite cooperation.

Although warm demanders must speak firmly, their tone should remain matter-

of-fact; they should never threaten, demean, or create power struggles. Students

will perceive such matter-of-fact demanding as evidence of their teacher's

commitment. Many teachers believe they are showing students they care when

they continually give "one more chance." Unfortunately, giving "one more chance"

demonstrates that a teacher does not mean what he or she says, and this

practice could be interpreted as a lack of caring.

Although classroom teachers have little control over many factors that affect

student engagement, they do have the means to create a supportive climate that

fosters engagement among high-poverty students. Warm demanders do so by

approaching their students with unconditional positive regard, knowing students

and their cultures well, and insisting that students perform to a high standard.

Students have told researchers that they want teachers who communicate that

they are "important enough to be pushed, disciplined, taught, and respected"

(Wilson & Corbett, 2001, p. 88). Such is the stance of the warm demander.

References

Bondy, E., Ross, D. D., Gallingane, C., & Hambacher, E. (2007). Culturally

responsive classroom management and more: Creating environments of success

and resilience. Urban Education, 42, 326348.

Charney, R. (2002). Teaching children to care. Greenfield, MA: The Northeast

Foundation for Children.

Corwin, M. (2001). And still we rise: Trials and triumphs of twelve gifted inner-city

high school students. New York: Harper Collins.

Cushman, K. (2003). Fires in the bathroom: Advice for teachers from high school

students. New York: The New Press.

Cushman, K., & Rogers, L. (2008). Fires in the middle school bathroom: Advice for

teachers from middle schoolers. New York: The New Press.

Esquith, R. (2004). There are no shortcuts. New York: Knopf.

Furrer, C., & Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children's

academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1),

148162.

EDEquity, Inc. All Rights Reserved

Leadership for Change

Irvine, J. J., & Fraser, J. W. (1998). Warm demanders. Education

Week, 17(35), 56.

Kleinfeld, J. (1975). Effective teachers of Eskimo and Indian

students. School Review, 83, 301344.

National Research Council. (2004). Engaging schools: Fostering high school

students' motivation to learn. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Ravet, J. (2007). Are we listening? Stoke on Trent, England: Trentham Books.

Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic

personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21, 95103.

Ross, D. D., Kamman, M., & Coady, M. (2007). Accepting responsibility for the

learning of all students: What does it mean? In M. Rosenberg, D. Westling, & J.

McLeskey (Eds.), Special education for today's teachers: An introduction (pp. 52

81). New York: Prentice Hall.

Ware, F. (2006). Warm demander pedagogy: Culturally responsive teaching that

supports a culture of achievement for African American students. Urban

Education, 41(4), 427456.

Wilson, B. L., & Corbett, H. D. (2001). Listening to urban kids: School reform and

the teachers they want. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Elizabeth Bondy (bondy@coe.ufl.edu; 352-392-9191, ext. 247) and Dorene D.

Ross (dross@coe.ufl.edu; 352-392-0751, ext. 238) are Professors in the College of

Education at the University of Florida at Gainesville.

Copyright 2008 by Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

EDEquity, Inc. All Rights Reserved

You might also like

- CBS StudentIdentityDocument4 pagesCBS StudentIdentityWilliam BuquiaNo ratings yet

- Helping Young Children Manage AngerDocument6 pagesHelping Young Children Manage AngerPopa Maria CristinaNo ratings yet

- Be Assertive LessonDocument1 pageBe Assertive Lessonapi-314568626No ratings yet

- Bucket FillersDocument63 pagesBucket FillersAnnetta WoolfolkNo ratings yet

- Cbs StudentvoiceDocument8 pagesCbs Studentvoiceapi-282945737No ratings yet

- Career Day Parent LetterDocument2 pagesCareer Day Parent Letterapi-233314088No ratings yet

- Small-Groupresultsreport KsDocument1 pageSmall-Groupresultsreport Ksapi-241401152No ratings yet

- 5th GRD Perseverance LessonDocument2 pages5th GRD Perseverance Lessonapi-242270654No ratings yet

- Flashlight Presentation Sexual Harassment LessonDocument14 pagesFlashlight Presentation Sexual Harassment Lessonapi-503399372No ratings yet

- Small Group Flashlight PresentationDocument22 pagesSmall Group Flashlight Presentationapi-503399372No ratings yet

- Career Day Parent Participation Form 2020 1 h0fb3lxbmzDocument2 pagesCareer Day Parent Participation Form 2020 1 h0fb3lxbmzapi-472378435No ratings yet

- Prepost PresentationDocument38 pagesPrepost Presentationapi-401545704No ratings yet

- Career Development Model 4-12Document21 pagesCareer Development Model 4-12api-279564185No ratings yet

- School Counseling Core Curriculum Action PlanDocument3 pagesSchool Counseling Core Curriculum Action Planapi-341833868No ratings yet

- Small Group CurriculumDocument3 pagesSmall Group Curriculumapi-299663993100% (1)

- Student Voice PamphletDocument2 pagesStudent Voice PamphletKen WhytockNo ratings yet

- Learn Assertive CommunicationDocument4 pagesLearn Assertive CommunicationAlbert FabroNo ratings yet

- Developmental psychology: Developmental psychology in childhood and adolescenceFrom EverandDevelopmental psychology: Developmental psychology in childhood and adolescenceNo ratings yet

- Learner Agency Teacher Activity SheetDocument4 pagesLearner Agency Teacher Activity SheetfriboNo ratings yet

- 4th Grade Study Skills LessonDocument2 pages4th Grade Study Skills Lessonapi-242270654No ratings yet

- Progressive Education In Nepal: The Community Is the CurriculumFrom EverandProgressive Education In Nepal: The Community Is the CurriculumNo ratings yet

- Quick and Easy Ways to Connect with Students and Their Parents, Grades K-8: Improving Student Achievement Through Parent InvolvementFrom EverandQuick and Easy Ways to Connect with Students and Their Parents, Grades K-8: Improving Student Achievement Through Parent InvolvementNo ratings yet

- Exploring the Evolution of Special Education Practices: a Systems Approach: A Systems ApproachFrom EverandExploring the Evolution of Special Education Practices: a Systems Approach: A Systems ApproachNo ratings yet

- Career and Multiple IntelligencesDocument7 pagesCareer and Multiple IntelligencesmindoflightNo ratings yet

- Common Cognitive DistortionsDocument4 pagesCommon Cognitive DistortionsJanel SunflakesNo ratings yet

- Puppet Handout PDFDocument4 pagesPuppet Handout PDFIvonneNo ratings yet

- Workbook: Emotional ResilienceDocument30 pagesWorkbook: Emotional ResilienceAzmyNo ratings yet

- 7 Cs of ResiliencyDocument10 pages7 Cs of ResiliencymortensenkNo ratings yet

- Small Group Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesSmall Group Lesson PlanCristina VasquezNo ratings yet

- Student Behavioural ReflectionDocument3 pagesStudent Behavioural Reflectionapi-369605818No ratings yet

- Boys 2 MENtors Curriculum Manual: A young men’s journey to self-empowerment and discovery through interactive activities and life-skills lessonsFrom EverandBoys 2 MENtors Curriculum Manual: A young men’s journey to self-empowerment and discovery through interactive activities and life-skills lessonsNo ratings yet

- Empowering Parents & Teachers: How Parents and Teachers Can Develop Collaborative PartnershipsFrom EverandEmpowering Parents & Teachers: How Parents and Teachers Can Develop Collaborative PartnershipsNo ratings yet

- Effective Inclusive Schools: Designing Successful Schoolwide ProgramsFrom EverandEffective Inclusive Schools: Designing Successful Schoolwide ProgramsNo ratings yet

- Bridging the Achievement Gap: What Successful Educators and Parents Do 2nd EditionFrom EverandBridging the Achievement Gap: What Successful Educators and Parents Do 2nd EditionNo ratings yet

- Triumph: A Curriculum for All Schools and UniversitiesFrom EverandTriumph: A Curriculum for All Schools and UniversitiesNo ratings yet

- GROW: My Own Thoughts and Feelings on Stopping the Hurt: A Child's Workbook About Exploring Hurt and AbuseFrom EverandGROW: My Own Thoughts and Feelings on Stopping the Hurt: A Child's Workbook About Exploring Hurt and AbuseNo ratings yet

- Who Do You Think You Are?: Three Crucial Conversations for Coaching Teens to College and Career SuccessFrom EverandWho Do You Think You Are?: Three Crucial Conversations for Coaching Teens to College and Career SuccessNo ratings yet

- Embracing Work Readiness in Teaching Language Arts: Volume 1From EverandEmbracing Work Readiness in Teaching Language Arts: Volume 1No ratings yet

- Actively Caring for People in Schools: How to Cultivate a Culture of CompassionFrom EverandActively Caring for People in Schools: How to Cultivate a Culture of CompassionNo ratings yet

- Cognitive and Behavioral Interventions in the Schools: Integrating Theory and Research into PracticeFrom EverandCognitive and Behavioral Interventions in the Schools: Integrating Theory and Research into PracticeRosemary FlanaganNo ratings yet

- Sense of Belonging Complete ModuleDocument97 pagesSense of Belonging Complete ModuleannieNo ratings yet

- School Engagement of High School StudentsDocument14 pagesSchool Engagement of High School StudentsBrowniepieNo ratings yet

- Dance Chaperone AssignmentDocument1 pageDance Chaperone Assignmentapi-302779030100% (1)

- Dance Chaperones Expectations 2018Document1 pageDance Chaperones Expectations 2018api-302779030No ratings yet

- Seconds Count Newsletter Final DraftDocument4 pagesSeconds Count Newsletter Final Draftapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Establishing Classroom RulesDocument1 pageEstablishing Classroom Rulesapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Drill Procedures Quick GuideDocument1 pageDrill Procedures Quick Guideapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Problem IndicatorsDocument1 pageProblem Indicatorsapi-302779030No ratings yet

- GriefDocument4 pagesGriefapi-83101465No ratings yet

- Pma Bell Schedule 18-19Document1 pagePma Bell Schedule 18-19api-302779030No ratings yet

- Tips For Teachers ParentsDocument2 pagesTips For Teachers Parentsapi-268684269No ratings yet

- Vision 2020 Strategic Plan FinalsubmissionDocument16 pagesVision 2020 Strategic Plan Finalsubmissionapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Pma Athletic Handbook 2017-18Document16 pagesPma Athletic Handbook 2017-18api-302779030No ratings yet

- Vision Core BeliefsDocument1 pageVision Core Beliefsapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Google Drive Quick Reference GuideDocument4 pagesGoogle Drive Quick Reference Guideapi-302779030100% (2)

- Csu BenchmarksDocument12 pagesCsu Benchmarksapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Powerteacher Pro For Teachers Traditional Grades - Users GuideDocument101 pagesPowerteacher Pro For Teachers Traditional Grades - Users Guideapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Rigor Relevance FrameworkDocument8 pagesRigor Relevance Frameworkapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Dok ChartDocument1 pageDok Chartapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Google Classroom Cheat SheetDocument6 pagesGoogle Classroom Cheat Sheetapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Marzanos High Yield StrategiesDocument5 pagesMarzanos High Yield Strategiesapi-238109871No ratings yet

- 11-12 Standards UnpackedDocument41 pages11-12 Standards Unpackedapi-302779030No ratings yet

- CoursefeedbackDocument12 pagesCoursefeedbackapi-302779030No ratings yet

- 9-10 Standards UnpackedDocument41 pages9-10 Standards Unpackedapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Ca Teaching StandardsDocument1 pageCa Teaching Standardsapi-302779030100% (1)

- CC Anchor StandardsDocument1 pageCC Anchor Standardsapi-302779030No ratings yet

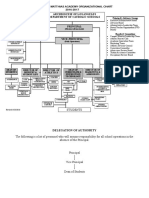

- ST Pius X-ST Matthias Academy Org Chart 16-17Document3 pagesST Pius X-ST Matthias Academy Org Chart 16-17api-302779030No ratings yet

- Justice of Ethic and Care - LittonDocument10 pagesJustice of Ethic and Care - Littonapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Pma Bellschedule 2016 Rev071716 MainDocument2 pagesPma Bellschedule 2016 Rev071716 Mainapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Understanding Filipino Culture and Differences Between Eastern and Western SocietiesDocument3 pagesUnderstanding Filipino Culture and Differences Between Eastern and Western SocietiesBethany Jane100% (1)

- Contemporary Issues ModuleDocument6 pagesContemporary Issues ModuleRoshann Marcus MamaysonNo ratings yet

- Isaiah - Berlin On MachiavelliDocument29 pagesIsaiah - Berlin On MachiavelliIan Tang0% (1)

- Demonology: Scripture Doctrine of DevilsDocument472 pagesDemonology: Scripture Doctrine of DevilsSakuraPinkCherry100% (3)

- The Interrelationships of Religion and DevelopmentDocument364 pagesThe Interrelationships of Religion and DevelopmentDanielNo ratings yet

- 2019, Data, Information, Evidence, and Knowledge - A Proposal For Health Informatics and Data ScienceDocument9 pages2019, Data, Information, Evidence, and Knowledge - A Proposal For Health Informatics and Data ScienceKoay FTNo ratings yet

- Cynthia Project Final Final - 1Document86 pagesCynthia Project Final Final - 1thesaintsintserviceNo ratings yet

- Understanding Hinduism Basic Questions Answered DC RaoDocument65 pagesUnderstanding Hinduism Basic Questions Answered DC RaoCliptec TrojanNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Modernization and Urbanization on Religion Among TeenagersDocument19 pagesThe Impact of Modernization and Urbanization on Religion Among TeenagersEmile Reviews & PlaysNo ratings yet

- Managing Filippino Teams - eBOOKDocument174 pagesManaging Filippino Teams - eBOOKong cher shyanNo ratings yet

- Emilio Gentile, Politics As Religion, First ChapterDocument16 pagesEmilio Gentile, Politics As Religion, First ChapterSabin Pandelea100% (2)

- 50 Common Cognitive Distortions - Psychology Today PDFDocument6 pages50 Common Cognitive Distortions - Psychology Today PDFfluidmindfulness100% (1)

- Some Aspects of Ashanti Religious BeliefsDocument27 pagesSome Aspects of Ashanti Religious BeliefsAtack MoshNo ratings yet

- Jeh 1Document2 pagesJeh 1hannah navarroNo ratings yet

- Passion (An Essay On Personality) - Roberto Mangabeira UngerDocument302 pagesPassion (An Essay On Personality) - Roberto Mangabeira UngerAlberto Sánchez GaleanoNo ratings yet

- Conspiracy TheoriesDocument143 pagesConspiracy TheoriesMark A. FosterNo ratings yet

- plsc-114 Introduction To Political PhilosophyDocument9 pagesplsc-114 Introduction To Political PhilosophyRogerio MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Religious Beliefs On Political ParticipationDocument22 pagesReligious Beliefs On Political ParticipationSheena PagoNo ratings yet

- Children's Spiritual Development StagesDocument3 pagesChildren's Spiritual Development StagesAamImaddudin100% (1)

- Innate Ideas and Stoic PhilosophyDocument31 pagesInnate Ideas and Stoic PhilosophyhermenericoNo ratings yet

- Key Concepts in Educational ManagementDocument94 pagesKey Concepts in Educational ManagementWan Rozimi Wan HanafiNo ratings yet

- Vision IAS Sociology Test-4-ModelAnswers - Unlocked (WWW - Freeupscmaterials.wordpress - Com) PDFDocument14 pagesVision IAS Sociology Test-4-ModelAnswers - Unlocked (WWW - Freeupscmaterials.wordpress - Com) PDFSantosh RoutNo ratings yet

- Christian Jambet - Four Discourses On The Authority of IslamDocument19 pagesChristian Jambet - Four Discourses On The Authority of IslamKenneth AndersonNo ratings yet

- Mastrofski (1999) - Policing For PeopleDocument12 pagesMastrofski (1999) - Policing For PeoplePoliceFoundationNo ratings yet

- Evaluating The Advocacy Coalition Framework - Jenkins-Smith and Paul A. SabatierDocument30 pagesEvaluating The Advocacy Coalition Framework - Jenkins-Smith and Paul A. SabatierMUHAMMAD IQBAL IRAWANNo ratings yet

- Serial Killers: Understanding Motives and PenaltiesDocument5 pagesSerial Killers: Understanding Motives and PenaltiesIgnatius TisiNo ratings yet

- Cultural Relativism and the Development of Moral CharacterDocument8 pagesCultural Relativism and the Development of Moral CharacterJamNo ratings yet

- Meaning and Facets of KnowledgeDocument20 pagesMeaning and Facets of KnowledgePratik Sah100% (4)

- Three Ideologies of Individualism PDFDocument21 pagesThree Ideologies of Individualism PDFDyann Sotéz GómezNo ratings yet