Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pryor J Is There Immediate Justification?

Uploaded by

Felipe Elizalde0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

52 views10 pagesa question

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documenta question

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

52 views10 pagesPryor J Is There Immediate Justification?

Uploaded by

Felipe Elizaldea question

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 10

Is There Immediate Justification?

I. James Pryor (and Goldman): Yes

A. Justification

i. I say that you have justification to believe P iff you are in a position where it would be

epistemically appropriate for you to believe P, a position where P is epistemically likely

for you to be true. I intend this to be a very inclusive epistemic status. (181)

ii. If there is some state or condition you are in in virtue of which you have justification to

believe P, I'll call it a justification-making condition, or a justification-maker for

short. (182).

iii. We can draw a distinction between having justification to believe P and appropriately

believing P. For the former, you needn't actually believe P, there simply must be things

that would make your believing P appropriate. For the latter, you must actually believe

P and satisfy several other conditions, like believing P for good reasons and taking

proper account of any evidence that may undercut your reasons for believing P. (Does

this distinction betray a type of internalism?)

B. Immediate Justification

i. The distinction between mediate and immediate justification is about type of epistemic

support, rather than either strength of support or how the belief was arrived at.

ii. Some justification is mediated. That is, sometimes your justification for believing some

proposition is constituted in part by the justification you have for other propositions.

This is one of the two ways that justification can be inferential. (Gas Gauge example)

iii. Immediate justification does not come from nowhere. It is precisely only justification

that does not come from justification for other beliefs.

iv. Although immediate justification does not come from other beliefs you have, it may be

the case that you need to have other beliefs in order for you to have the belief for which

you're immediately justified (e.g. beliefs that may be required in order for you to have

relevant concepts).

v. Immediately justified beliefs will usually be defeasible.

vi. Beliefs can be epistemically overdetermined; you can be justified in believing one and

the same thing both mediately and immediately.

C. Why Believe in Immediate Justification?

i. The (Justification-Making) Regress Argument

a) Four different options

Justificatory chain goes on forever.

Justificatory chain includes some closed loops.

Justificatory chain ends in unjustified belief.

Justificatory chain ends in justified belief that is not justified in virtue of any

other belief.

b) Foundationalist argues that first two are untenable (but, according to Pryor, whether

or not they are is not simply obvious, so it's better to turn to a different argument).

ii. The Argument from Examples

a) Suppose I feel tired, or have a headache. I am justified in believing I feel those

ways. And there do not seem to be any other propositions that mediate my

justification for believing it. What would the other propositions be? (184)

b) I am imagining my grandmother. The way I am imagining her is sitting in her

kitchen. Or at least I believe it is. And it seems I could be justified in that belief.

Again, it is hard to see what other propositions might mediate this justification.

(185)

iii. (A methodological point: Goldman says that the defender of immediate justification

must answer three different questions: Are there immediately justified beliefs? How is

immediate justification possible? What is it in virtue of that some states give rise to

immediately justified beliefs? Pryor, in this paper, seems only to be concerned with

answering the first two. How important, then, should we think answering the third is?)

D. The Master Argument for Coherentism

i. Foundationalist views and Given Theories are two non-identical subsets of views that

believe in immediate justification.

ii. Coherence theories deny that there is any immediate justification all justification, they

say, comes at least in part from justification of other beliefs.

a) Pure coherentists claim that a belief can only be justified by other beliefs.

b) Impure coherentists claim that some non-beliefs can play a justifying role (such as

experiences).

iii. (A separate problem from Goldman: Justification is, at least in inferential beliefs,

transferred from one belief or set of beliefs to another. But that which gives rise to the

justification in these basic beliefs is not itself justified. So where does the justification

come from? Is it just created ex nihilo?)

iv. The Master Argument (historically directed at the Given Theory): In order for any

cognitive state to justify any other state, it must have assertive or representational

content. But any state which has such content must itself be justified.

a) The Content Requirement: In order to be a justifier, you need to have (assertive)

propositional content.

Only propositions can stand in logical relationships with one another. The most

that a sensation can have with a belief is a causal relationship, which cannot

show how or why the belief is justified (cf. Davidson quote pp. 186-187)

b) Only beliefs or states like beliefs which require epistemic justification have

(assertive) propositional content.

c) Conclusion: Only beliefs (or similar states) can be justifiers.

v. Worries about the argument

a) It could be that all beliefs require justification, but are sometimes able to justify

others without being justified themselves. If so, the beliefs so justified would count

as immediately justified.

b) Is this really an argument for coherentism? Where does coherence come in?

Coherence is not a belief. (Coherentist reply: justification always comes from

content of beliefs, coherence is just shorthand for talk about which sets of beliefs

justify and which don't)

c) Experiences have assertive propositional content but are not beliefs or even very

similar to beliefs. For one, they aren't the types of things it seems possible to justify.

Therefore, the Master Argument has not given us reason to exclude experiences

from the ranks for justifiers. (Counterexample to 'Only Beliefs').

d) (From Goldman on Pryor: For one, it is questionable whether experiences have

assertive propositional content. Some, like the experience of a headache, seem not

to, and even if they did, you'd need to say what the relationship is between the belief

content and the experience content such that the one can justify the other (cf.

Goldman on Feldman))

vi. What about the Content Requirement?

a) Seems to be motivated by Premise Principle: The only states with propositional

content that can be justifiers for P are those that can stand in an inferential relation to

P; that is, those that can be used as premises in an argument for P.

b) Experiences cannot fit this requirement because the contents of the experiences

typically say nothing about who is experiencing them.

The Premise Principle is about what justifies beliefs, not the process by which

you come to have beliefs. So it is possible for your belief to be supported by

inferential relations without your actually inferring anything. So, the experience

as of your having hands could justify your having hands, even if the

experience gives your belief justification immediately.

The Premise Principle does not straightforwardly entail coherentism. (It allows

that an experience as of your having hands could justify the belief that you

have hands)

Nor is the Premise Principle implied by the view that perceptual justification is

mediated. For the latter view says nothing about what justifies our beliefs about

our experiences. Perhaps, contra the Premise Principle, we are justified in those

beliefs merely by virtue of having the experiences. (191)

c) Why believe the Premise Principle...

E. Avoiding Arbitrariness

i. Objection: If experiences have no representational content, it would just be arbitrary to

say they support any one belief rather than another.

ii. Possible response: Perhaps experiences do have representational content, or some other

sort of content or logical structure (like some philosophers think events have) by which

they can serve as justifiers.

iii. (Question: Is this response enough? Depends on where the burden of proof lies.)

F. Evidence and Reasons

i. Justifiers are things that make your beliefs epistemically appropriate. Often, in the place

of justifier, philosophers will use words like evidence or reasons. But insofar as

evidence and reasons are things that can probabilify hypotheses, and are things that the

hypotheses can be inconsistent with or explain, it seems there is good reason to think

they must be propositional.

ii. Response: Evidence and justifier may not be perfect synonyms. Consider that we

sometimes use the terms 'belief' and 'desire' to refer to propositions that one believes and

desires, rather than to one's states of believing or desiring them. Similarly, I think,

sometimes we use 'evidence' to refer to propositions that are evident to one, rather than

to the states that make them evident. (193)

iii. Typically, when we ask for someone's reasons or justification for some belief, we are

looking for an argument. But an argument has premises, and only propositions can be

premises.

iv. Response: This way of using the word reason, which we can call the dialectical notion

of a reason, need not be the only one. We can make a distinction between justification-

showers and justification-makers.

G. Grounding and Being Guided by Norms

i. What does it take for a belief to be properly grounded? A natural thought is that your

belief in P is properly grounded if you are in some condition C and your belief is formed

(or sustained) in a way that is guided by the epistemic norm When in C, believe P.

ii. An epistemic norm is a claim about how we should be, in epistemic matters. (195)

iii. We can make a distinction between believing in accordance with an epistemic norm and

being guided by an epistemic norm, just like we can make a distinction between acting

in accordance with a reason and acting for that reason.

iv. So what is it to be guided by an epistemic norm? Since we can do things all the time

that involve being guided by norms without actually thinking about the norms (like

figuring out why a computer isn't working or playing a musical instrument), we must not

have a view that requires too much reflectiveness or deliberateness. We must be even

more skeptical of such a view given that it doesn't seem believing is ever an action of

ours.

v. Until we do have a satisfactory view about this, there's no guarantee that it will be one

that vindicates the Premise Principle.

II. Michael Williams: No

A. What Are Basic Beliefs?

i. To say that someone is justified in believing P is to say they are epistemically entitled to

believe P.

ii. Justification is a normative notion it has to do with whether one's beliefs meet

epistemic standards.

iii. The purpose of the the standards must be that they somehow help us in our goal of

having true beliefs.

iv. The debate about basic beliefs is not just about whether there is a difference between

things you conclude on the basis of argument and those you just see.

a) Basic beliefs are the stock in trade of foundationalists.

b) Theoretical commitments of foundationalists include:

Traditional foundationalism is substantive, rather than merely formal.

According to substantive foundationalism, the class of basic beliefs is

theoretically tractable. In particular, there are non-trivially specifiable kinds of

beliefs, individuated by broad aspects of their content, that are fitted to play the

role of terminating points for chains of justification. The distinction between

basic and non-basic beliefs is thus ontological rather than merely

methodological. (203)

Foundationalism is strong. Basic beliefs are meant to be indubitable or (weaker)

incorrigible. Basic beliefs always count as knowledge.

Traditional foundationalism is atomistic. Basic beliefs provide absolute

terminating points for justificatory chains. To do so, basic beliefs must be

independent both epistemically and semantically of other justified beliefs. Since

basic beliefs constitute encapsulated items of knowledge, there is no objection in

principle to the idea of a first justified belief.

Traditional foundationalism is radically internalist. The justification-making

factors for beliefs, basic and otherwise, are all open to view, aand perhaps even

actual objects of awareness. At the base level, when I know that P, I am always

in a position to know that I know that P, and perhaps even always do know that I

know that P.

c) Common-sense examples of non-inferential beliefs do not obviously meet these

conditions.

Ordinary examples of non-inferential beliefs come in a bewildering variety,

displaying no obvious theoretical integrity.

Ordinary non-inferential beliefs seem often to be only prima facie justified,

hence corrigible. (204)

Having ordinary non-inferential beliefs requires a mastery of concepts that

makes the beliefs not semantically free-standing.

Many non-inferential beliefs result from the unselfconscious exercise of

generally reliable faculties, without, it seems, any need for being able to assess

the reliability of those faculties.

v. Basic belief is a theoretical concept which plays a part in a distinctively philosophical

program. Therefore, common-sense examples will not be enough to settle the issue of

whether there are any basic beliefs.

B. The Agrippan Argument

i. Foundationalists argue that if you aren't a foundationalist, you must be a coherentist,

which is open to fatal objections. Coherentists argue that if you aren't a coherentist, you

must be a foundationalism, which is open to fatal objections.

ii. But why think these are the only two options? Why think we need to have a theory of

knowledge at all?

iii. Theories of knowledge can be seen as trying to answer skeptical arguments about the

possibility of knowledge.

a) Agrippa's trilemma: Find a belief that is justified inferentially. Ask how that belief is

justified. If further propositions are brought up, ask how belief in those is justified.

If further propositions are brought up, ask how belief in those is justified....

Either the justificatory chain goes on forever.

The justificatory chain stops with a proposition for which there is no

justification.

The justificatory chain eventually traces back to reasons that include the original

belief for which justification was sought.

b) Most epistemologists accept one of the options, though they put a better face on

them. Foundationalists take the second, but claim the chain-stopping belief can be

justified all by itself. Coherentists take the third, but say that the circle is not vicious

because justification is not linear.

For foundationalists, justification is atomistic and bottom up.

For coherentists, justification is holistic and top down.

C. Skepticism and Philosophical Understanding

i. The skeptic's question, as mentioned above, is about the possibility of knowledge in

general. Any explanation of knowledge that takes some things for granted as known

will fail to satisfy the skeptic. The skeptic imposes a Totality Condition on a properly

philosophical understanding to knowledge and justification.

ii. The Totality Condition creates pressure to accept internalism about justification and

knowledge, which says that in order to be justified in believing something, we must

have some sort of cognitive access to the things by which the belief is justified.

iii. Externalism, on the other hand, says that a belief can be justified simply in virtue of the

process by which it is generated, irregardless of whether the believer has any knowledge

at all about that process. Presumably, the 'knowledge' we attribute to animals is like

this. According to externalists, human knowledge is not essentially different. (207)

iv. Prima facie, internalism is not particularly plausible, at least if it is taken as a fully

general view of ordinary justification...However, in the peculiar context of the skeptical

challenge, it is easy to persuade oneself that externalism is not an option. (207)

v. The externalist can easily sketch a coherent way the world might be such that we have

knowledge, but it is not enough to answer the skeptic to show that knowledge is a

logical possibility. We want a replay not just to the claim that we know nothing, but

also to the meta-skeptical claim that for all we know, we know nothing. This too pushes

us towards internalism. (207)

vi. Also, philosophy is a reflective discipline and is usually conducted from a first-person

standpoint. Externalism analyses knowledge from a third-person point of view.

vii. It is these internalist-leaning features of the skeptical problem that explain the

otherwise puzzling features of traditional foundationalism.

D. The Appeal to the Given

i. Wilfrid Sellars coined the phrase the Myth of the Given to refer to the doctrine that

some things are immediately knwn...In my view, Sellars's objections to the Myth have

never been successfully rebutted. Recent would-be resurrections of traditional

foundationalism are just attempts to square the same old circles. The repetitiveness of

the debate reflects constraints on a solution to skepticism that are built into the way

foundationalists understand the problem. (209)

ii. Basic beliefs are often said to be self-evident or self-justifying, but there must be a

distinction between those involving necessary truths (like mathematical beliefs, where

understanding a proposition is a sufficient condition for recognizing its truth), and those

involving empirical judgments.

iii. Schlick on the given

a) A priori judgments are analytic; that is, true by virtue of meaning.

b) Empirical judgments, though not analytic, resemble analytic judgments.

c) There are two sorts of meaning-generating rules

Discursive definitions, which generate analytic truths

Ostensive definitions, which introduce empirical content to the language

d) Basic observational judgments essentially involve indexical terms

e) Observation-terms (like red) can be understood phenomenally.

f) So, when I say, for example, this is red, I must both be focusing on something

currently present in my experience and I must have a good grasp of what sorts of

things are called red. Given this, the only way I could be mistaken is by either

focusing on the wrong thing or misapplying the rule for picking out red things. Since

I am unlikely to be making those errors, its hard to see how I could be mistaken in

my judgment, even though it reports a genuine empirical fact.

iv. Since this account relies on my ability to consistently pick out red things, doesn't it

sneak in a reliability condition?

v. The standard reaction to this question is to insist that purely phenomenal concepts must

not just cancel any implications of extra-experiential existence: they must also be non-

comparative. But how does This is (non-comparatively) F differ from This is hat it

is? Basic judgments threaten to buy their immunity from error at the cost of being

drained of descriptive content altogether (210)

vi. Traditional foundationalists think it is important that the contents of sensory experience

are directly apprehended. Their view contains, then, three important elements: the

sensory experience, the basic belief or judgment that the experience is of such and such

a character, and some kind of relation between the experience and the judgment which

underwrites the judgment's epistemic appropriateness. But what is this relation?

vii. The contents of sense-experience have traditionally been thought of as pre-

conceptual qualitative particulars with which one is directly acquainted. Knowledge

comes from the conceptualization of this raw material.

viii. But, Sellars asks, how can this raw material ever lead to belief without being

conceptual? If it has no propositional content, it cannot function as a reason for a belief,

and if it is, then we haven't really explained the epistemic authority of the knowledge.

ix. Russellian acquaintance is suppoed to be sui generis, distinct from both knowing how

and knowing that We have no pretheoretical understanding of the appeal of the given

and, if the argument of the previous paragraph is correct, no theoretical understanding

either. Talk of the given, or knowledge by acquaintance, is a deus ex machina,

introduced to do the job epistemologists think that they need to get done. It has no other

justification. (211)

x. Talk of acquaintance with facts won't help either: Such understanding as we have of

talk of acquaintance with facts is derived from our common-sense conception of seeing

that things are thus and so. (212)

xi. Bonjour on the given

a) Sensory awareness involves a constitutive non-apperceptive awareness of its

content.

b) The relationship between the sensory content and judgment is neither logical nor

causal it is descriptive.

c) Descriptions will have more or less accuracy of fit with the object described (ie, the

sensory content).

d) Since the object being described is a conscious state, it is one with which we are

directly acquainted, so there is no need for further conceptual description.

xii. Replies

a) Bonjour still hasn't given any non-ad-hoc reason for thinking we can have a non-

conceptual awareness of the content of our experiences.

b) Even if he had, he hasn't given any reason to think judgments come to in such a way

would be justified. Maybe we are really bad at describing the contents of our

experience.

c) Bonjour's motivation for saying that we can be directly aware of a judgment's fit

with the contents of our experience is to stop an infinite regress, which he sees as

artificial and not in need of answering. But the hardcore externalist says the same

thing about the skeptical regress. Why accept this in one case and not the other?

E. Conclusion

i. If we can't have basic beliefs, and coherentism is badly flawed, we may just have to give

up on trying to get the type of philosophical theory of knowledge epistemologists have

traditionally sought.

ii. It may be the case that, like with rules of fair play, all we can give are some very

specific constraints on justification and never a systematic theory.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Soble Alan A History of Erotic Philosophy PDFDocument18 pagesSoble Alan A History of Erotic Philosophy PDFFelipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- MarquisDocument307 pagesMarquisFelipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Stewart R Nietzsche's Perspectivism & Autonomy of The Master Type 86Document20 pagesStewart R Nietzsche's Perspectivism & Autonomy of The Master Type 86Felipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Axel Honneth - The Critique of PowerDocument373 pagesAxel Honneth - The Critique of PowerRafael Marino100% (5)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- KatsafanasDocument22 pagesKatsafanasFelipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Boring E A History of Experimental Psychology 50Document13 pagesBoring E A History of Experimental Psychology 50Felipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- 3 Kinds of NaturalismDocument15 pages3 Kinds of NaturalismFelipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Great ConvergenceDocument340 pagesThe Great ConvergenceFelipe Elizalde100% (2)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Sedgwick P Nietzsche's Economy Modernity Normativity & Futurity 07 PDFDocument231 pagesSedgwick P Nietzsche's Economy Modernity Normativity & Futurity 07 PDFFelipe Elizalde100% (1)

- Boring, E. G. (1950) - A History of Experimental PsychologyDocument799 pagesBoring, E. G. (1950) - A History of Experimental Psychologyifmelojr100% (2)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Schellenberg S The Unity of Perception Content Consciousness Evidence 18 PDFDocument268 pagesSchellenberg S The Unity of Perception Content Consciousness Evidence 18 PDFFelipe Elizalde100% (1)

- Steger M Globalization A Very Short Introduction 03Document29 pagesSteger M Globalization A Very Short Introduction 03Felipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Rosa L Logical Principles of Agnosticism 18Document21 pagesRosa L Logical Principles of Agnosticism 18Felipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Lankavatara Sutra, A Mahayana Text. Transl. by D. T. Suzuki (1932) PDFDocument362 pagesLankavatara Sutra, A Mahayana Text. Transl. by D. T. Suzuki (1932) PDFJason50% (2)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Dafermos M Relating Dialogue & Dialectics A Philosophical Perspective 18 PDFDocument18 pagesDafermos M Relating Dialogue & Dialectics A Philosophical Perspective 18 PDFFelipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Sellars and The "Myth of The Given": Syracuse UniversityDocument18 pagesSellars and The "Myth of The Given": Syracuse UniversityFelipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Ott W Descartes Malebranche & The Crisis of Perception 17Document259 pagesOtt W Descartes Malebranche & The Crisis of Perception 17Felipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- Friedrich Albert Lange The History of Materialism and CriticismDocument362 pagesFriedrich Albert Lange The History of Materialism and CriticismDaniel CifuentesNo ratings yet

- Katsafanas P Agency Foundations of Ethics Nietzschean Constitutivism 13 PDFDocument280 pagesKatsafanas P Agency Foundations of Ethics Nietzschean Constitutivism 13 PDFFelipe Elizalde100% (1)

- Bandini Aude Perception & Its Givenness 15Document17 pagesBandini Aude Perception & Its Givenness 15Felipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Mind A-Z: Marina RakovaDocument221 pagesPhilosophy of Mind A-Z: Marina RakovavehapkolaNo ratings yet

- The Great ConvergenceDocument340 pagesThe Great ConvergenceFelipe Elizalde100% (2)

- Ugresic D & The Museum of Unconditional Surrender 02 PDFDocument232 pagesUgresic D & The Museum of Unconditional Surrender 02 PDFFelipe Elizalde100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Thomas D Hacker Culture 02Document296 pagesThomas D Hacker Culture 02Felipe Elizalde100% (1)

- Macarthur D Pragmatism Metaphysical Quietism & The Problem of NormativityDocument31 pagesMacarthur D Pragmatism Metaphysical Quietism & The Problem of NormativityFelipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- Tucan D The Quarrel Between Poetry & Philosophy 12 PDFDocument8 pagesTucan D The Quarrel Between Poetry & Philosophy 12 PDFFelipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- Gironi F What Has Kant Ever Done For Us Speculative Realism & Dynamic KantianismDocument25 pagesGironi F What Has Kant Ever Done For Us Speculative Realism & Dynamic KantianismFelipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- Beckermann A Is There A Problem About Intentionality 1996Document23 pagesBeckermann A Is There A Problem About Intentionality 1996Felipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- Murray D J 'A Perspective For Viewing The History of Psychophysics' 1993Document72 pagesMurray D J 'A Perspective For Viewing The History of Psychophysics' 1993Felipe ElizaldeNo ratings yet

- Goldman A & Whitcomb D Eds Social Epistemology Essential Readings 2011 PDFDocument368 pagesGoldman A & Whitcomb D Eds Social Epistemology Essential Readings 2011 PDFFelipe Elizalde100% (2)

- L, Women: Craig S. KeenerDocument65 pagesL, Women: Craig S. KeenerOlivera PantićNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Ethics ChartDocument12 pagesEthics Chartmadhat32No ratings yet

- English 10 - Argumentative Essay Quarter 2 - Week 2Document2 pagesEnglish 10 - Argumentative Essay Quarter 2 - Week 2axxNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Epistemology Oral Comprehensive Examination QuestionsDocument3 pagesContemporary Epistemology Oral Comprehensive Examination QuestionsMark Anthony DacelaNo ratings yet

- What Is A Case Study?: Malin KarlssonDocument10 pagesWhat Is A Case Study?: Malin KarlssonReena ReenaRaniNo ratings yet

- Conceptual FrameworkDocument4 pagesConceptual FrameworkEustass KiddNo ratings yet

- 15.syllogism GNDocument3 pages15.syllogism GNChaya DeepikaNo ratings yet

- A Primer of Indian LogicDocument386 pagesA Primer of Indian LogicRohit100% (1)

- Argumentative Writing - Lecture NoteDocument17 pagesArgumentative Writing - Lecture NoteSue SukmaNo ratings yet

- Learner Guide For Cambridge International As Level English General Paper 8021 For Examination From 2019Document47 pagesLearner Guide For Cambridge International As Level English General Paper 8021 For Examination From 2019Nikhil Jain100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Coins Philadelphia Baseball Cards - Chicago Comic Books - San Diego Stamps - AtlantaDocument8 pagesCoins Philadelphia Baseball Cards - Chicago Comic Books - San Diego Stamps - AtlantaKing JaydeeNo ratings yet

- Fuzzy Decision TreesDocument12 pagesFuzzy Decision TreesVu Trung NguyenNo ratings yet

- As-000192 1Document229 pagesAs-000192 1BHFkonyvtarNo ratings yet

- Traditional Square of OppositionDocument1 pageTraditional Square of OppositionDenise GordonNo ratings yet

- Notas Como Texto Bradford P. Keeney PHD - Aesthetics of Change (1983)Document36 pagesNotas Como Texto Bradford P. Keeney PHD - Aesthetics of Change (1983)Redmi AJNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 - Melchert, Morrow (Selected Sections)Document23 pagesChapter 9 - Melchert, Morrow (Selected Sections)AlphaNo ratings yet

- Conotation and Denotation of The Short Story PrintDocument14 pagesConotation and Denotation of The Short Story PrintSabila NurazizahNo ratings yet

- Vianzon, Reynaldo JR., M BSN Logic: InferenceDocument2 pagesVianzon, Reynaldo JR., M BSN Logic: InferenceSarah BenjaminNo ratings yet

- Konstruktivizam I NaukaDocument304 pagesKonstruktivizam I NaukadakintaurNo ratings yet

- SYLLABUSgenedDocument232 pagesSYLLABUSgenederizza50% (2)

- Module 5 FunctionsDocument47 pagesModule 5 FunctionsSoham PatilNo ratings yet

- 6 Rules of Categorical SyllogismDocument16 pages6 Rules of Categorical SyllogismYvette Dizon100% (1)

- Nyaya - WikipediaDocument17 pagesNyaya - WikipediaPraveen BagadiNo ratings yet

- Von Neumann-On Rings of Operators IIIDocument69 pagesVon Neumann-On Rings of Operators IIIAlice Yipper-VindauNo ratings yet

- Cmosedu Com Jbaker Courses Ee421L f13 Students Wolvert9 LabDocument15 pagesCmosedu Com Jbaker Courses Ee421L f13 Students Wolvert9 LabPerumal NamasivayamNo ratings yet

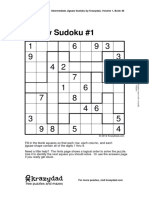

- SSDOKUDocument10 pagesSSDOKUJessanin Calipayan100% (1)

- Mathematical Reasoning Basics ExplainedDocument4 pagesMathematical Reasoning Basics ExplainedJanardhan KNo ratings yet

- Notes Important Questions Answers of 11th Math Chapter 8 Excercise 8.1Document24 pagesNotes Important Questions Answers of 11th Math Chapter 8 Excercise 8.1shahidNo ratings yet

- Iteration and Recursion: CPE222 - Discrete StructuresDocument10 pagesIteration and Recursion: CPE222 - Discrete StructuresAhmed SaidNo ratings yet

- MATH 204-Introduction To Formal Mathematics-Dr - Shamim Arif PDFDocument3 pagesMATH 204-Introduction To Formal Mathematics-Dr - Shamim Arif PDFMinhal MalikNo ratings yet

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYFrom EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Stoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessFrom EverandStoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (83)