Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Antithrombotic Therapy For Venous Thromboembolic Disease PDF

Uploaded by

Roberto López MataOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Antithrombotic Therapy For Venous Thromboembolic Disease PDF

Uploaded by

Roberto López MataCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Review & Education

JAMA Clinical Guidelines Synopsis

Antithrombotic Therapy for Venous Thromboembolic Disease

Atul Jain, MD, MS; Adam S. Cifu, MD

GUIDELINE TITLE Antithrombotic Therapy for Venous In patients with cancer and DVT or PE (cancer-associated

Thromboembolic Disease thrombosis), low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is

preferred over VKA therapy, dabigatran, rivaroxaban,

RELEASE DATE February 2016 apixaban, or edoxaban (grade 2C).

In patients with an unprovoked DVT or PE who are stopping

PREVIOUS GUIDELINE 2012 anticoagulant therapy and do not have a contraindication

to aspirin, aspirin therapy is suggested (grade 2B).

DEVELOPER American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) In patients with low-risk PE and adequate home

circumstances, treatment at home or brief hospitalization

FUNDING SOURCE ACCP (vs traditional 5 days of inpatient treatment) is suggested

(grade 2B).

TARGET POPULATION Patients with deep venous thrombosis In patients with subsegmental PE (no involvement of

(DVT) of the leg or pulmonary embolism (PE) more proximal pulmonary arteries) and no proximal DVT

in the legs who have a low risk of recurrent venous

MAJOR RECOMMENDATIONS thromboembolism (VTE; not hospitalized, normal mobility,

In patients without cancer and lower extremity DVT or PE, no active cancer, and presence of reversible risk factor),

anticoagulation with dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, or clinical surveillance is suggested over anticoagulation

edoxaban is preferred over vitamin K antagonist (VKA) (grade 2C). In similar patients without these markers

therapy (grade 2B). of low risk, anticoagulation is suggested (grade 2C).

Summary of the Clinical Problem assessed using a validated tool. Prospective cohort studies were in-

TheestimatedannualincidenceofVTE,definedasDVTofthelegorPE, cluded in the search when identified randomized trials were deemed

ranges from 104 to 183 per 100 000 person-years.1 Compared with inadequate. Meta-analyses were performed on the pooled data.

those without VTE, the 30-year mortality risk is increased for survivors Selected studies were assessed for risk of bias using the Cochrane

of an episode of VTE and for survivors of an episode of PE (64 vs 136 Risk of Bias Tool.5 The quality of evidence and strength of recom-

and 211 per 1000 person-years, respectively).2 In 2012, the ACCP re- mendations were categorized using the GRADE approach.6 Exter-

leasedtheninth-editionguidelinesforantithrombotictherapyandpre- nal peer review was conducted after panel consensus was achieved

vention of thrombosis.3 Since the publication of that guideline, there on the drafted recommendations and before publication of the

has been improved understanding of the diagnosis and prognosis of guidelines. No public commentary was obtained.

VTE. The addition of nonvitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOACs) has al-

tered the landscape of treatment options. This update addresses the Benefits and Harms

role for NOACs and provides new recommendations for management In patients without cancer and VTE, NOACs are preferred over VKAs

of subsegmental PE and treatment of cancer-associated VTE. for anticoagulant therapy (grade 2B). This preference is based on data

demonstrating that the risk reduction for long-term recurrent VTE

Characteristics of the Guideline Source

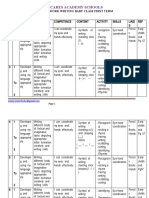

This statement was funded by the ACCP (Table). An oversight commit-

tee at Chest appointed an editor for this guideline who nominated the Table. Guideline Rating

members of the writing group. Panelists were required to disclose any Standard Rating

potential conflicts of interest (COIs),4 which were classified as primary Establishing transparency Good

orsecondary;panelistswithprimaryCOIswererequiredtoabstainfrom Management of conflict of interest in the guideline Fair

voting on related topic areas but could participate in discussions pro- development group

vided they refrained from strong advocacy. Of the topics reviewed for Guideline development group composition Good

this synopsis, those relating to use of NOACs in patients with VTE with- Clinical practice guidelinesystematic review intersection Good

out cancer and to use of LMWH in patients with VTE with cancer were Establishing evidence foundations and rating strength Good

for each of the guideline recommendations

notable for more serious COIs among the majority of panelists.

Articulation of recommendations Good

External review Fair

Evidence Base

Updating Good

A literature search was conducted for articles published between

Implementation issues Good

1946 and July 2015. The quality of identified systematic reviews was

2008 JAMA May 16, 2017 Volume 317, Number 19 (Reprinted) jama.com

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/jama/936236/ by Roberto Lopez Mata on 05/17/2017

JAMA Clinical Guidelines Synopsis Clinical Review & Education

with dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, or edoxaban is similar to the no episodes of recurrent VTE were observed. These data led the

risk reduction with VKAs, while the risk of bleeding is generally less guideline authors to suggest that in similar patients who are at low

with NOACs than with VKAs. risk of recurrent VTE (defined as not being hospitalized, not having

In patients with cancer-associated thrombosis (VTE and can- reduced mobility, not having active cancer, and having a reversible

cer), LMWH is preferred over VKAs for long-term anticoagulant risk factor for DVT), surveillance for proximal DVT with serial du-

therapy (grade 2C). This preference is based on a meta-analysis of plex imaging is suggested over anticoagulant therapy. In patients with

9 randomized trials comparing LMWH with VKAs or NOACs with isolated subsegmental PE who have poor cardiopulmonary re-

VKAs suggesting that LMWH was more effective than NOACs in can- serve, decreased mobility, active cancer, or irreversible VTE risk fac-

cer-associated thrombosis (grade 2C); however, this finding may be tors, anticoagulant therapy is favored over surveillance.

attributed to differences among study populations and design.7

In patients with creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min, VKA Discussion

therapy is preferred, as most NOACs and LMWH are contraindi- Treatment of VTE has changed markedly over the last 4 years with

cated in the setting of severe renal impairment. the advent of NOACs. Concurrent with greater use of highly sensi-

NOACs provide greater convenience for patients than VKAs be- tive computed tomographic pulmonary angiography in the diagno-

cause these drugs do not require international normalized ratio moni- sis of VTE, the incidence of PE has increased by 81%, from 62.3 to

toring. However, higher pricing may limit access and adherence to 112.3 per 100 000 US adults between 1998 and 2006, with up to

NOACs. Furthermore, dabigatran may increase risk of acute coro- 15% of PE diagnoses now being attributed to isolated subsegmen-

nary syndromes in some populations.8 tal PE. Among patients with isolated subsegmental PE, 7% may ex-

Aspirin is likely less effective than anticoagulant therapy for pre- perience a major bleeding episode during treatment.10 Retrospec-

venting recurrent VTE. In patients with unprovoked VTE who dis- tive analyses suggest that the risk of recurrent VTE may be very low,

continue anticoagulant therapy after a 3-month treatment course estimated at 0% (95% CI, 0%-7.4%).10 This guideline is the first to

and who are not at increased bleeding risk, a pooled analysis sug- make recommendations that take these changes into account.

gests that extended treatment with aspirin is associated with re-

duced risk of recurrent VTE vs placebo, with an absolute risk reduc- Areas in Need of Future Study or Ongoing Research

tion of 5.3% and a hazard ratio of 0.65 (95% CI, 0.49-0.86). An While a variety of patient-specific factors may guide selection of

increased risk of bleeding associated with aspirin use is not statis- specific anticoagulants for long-term treatment of VTE, compara-

tically significant (hazard ratio, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.48-3.53).3 The au- tive effectiveness studies are needed to identify whether any spe-

thors of the guideline do not specify a recommended aspirin dos- cific NOACs provide superior risk reduction for recurrent VTE or

age, but 100 mg/d is suggested based on a 2014 meta-analysis.9 whether specific drugs are most effective in specific circumstances.

Outpatient anticoagulant therapy is suggested over hospital- Similar studies are also needed to directly compare the effective-

ization in patients with acute PE if a patient feels well enough to be ness of NOACs and LMWH in the treatment of cancer-associated

treated at home (grade 2B). The authors suggest that this strategy thrombosis. NOACs, if found to be noninferior or superior to

should be limited to low-risk patients who are clinically stable; have LMWH, would provide an alternate treatment for patients who pre-

good cardiopulmonary reserve; have no serious comorbidities such fer to avoid injecting LMWH. Finally, randomized clinical trials are

as recent bleeding, severe renal or liver disease, or severe throm- needed to define the utility of antithrombotic treatment for iso-

bocytopenia; and are likely to adhere to anticoagulant therapy. In- lated subsegmental PE.

patient treatment is indicated for patients with evidence of right ven-

tricular dysfunction or elevated cardiac biomarkers.

Related Guidelines and Other Resources

The authors of the guideline did not identify any randomized

trials of patients with isolated subsegmental PE. In a number of small Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement Health Care Guideline:

retrospective analyses of patients with isolated subsegmental PE and Venous Thromboembolism Diagnosis and Treatment (January 2013)

no proximal DVT who were not receiving anticoagulant therapy,

ARTICLE INFORMATION 2. Sgaard KK, Schmidt M, Pedersen L, et al. 7. Carrier M, Cameron C, Delluc A, et al. Efficacy

Author Affiliations: Division of Consultative 30-year mortality after venous thromboembolism. and safety of anticoagulant therapy for the

Medicine and Division of Preventive, Occupational Circulation. 2014;130(10):829-836. treatment of acute cancer-associated thrombosis.

and Aerospace Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, 3. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Thromb Res. 2014;134(6):1214-1219.

Arizona (Jain); University of Chicago, Chicago, Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease. Chest. 8. Uchino K, Hernandez AV. Dabigatran association

Illinois (Cifu). 2012;141(2)(suppl):e419S-e494S. with higher risk of acute coronary events. Arch

Corresponding Author: Adam S. Cifu, MD, 4. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Intern Med. 2012;172(5):397-402.

University of Chicago, 5841 S Maryland Ave, Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease. Chest. 9. Simes J, Becattini C, Agnelli G, et al. Aspirin

MC 3051, Chicago, IL 60637 2016;149(2):315-352. for the prevention of recurrent venous

(adamcifu@uchicago.edu). 5. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gtzsche PC, et al. thromboembolism. Circulation. 2014;130(13):

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have The Cochrane Collaborations tool for assessing risk 1062-1071.

completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. 10. Peiman S, Abbasi M, Allameh SF, et al.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. 6. Balshem H, Helfand M, Schnemann HJ, et al. Subsegmental pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res.

GRADE guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4): 2016;138:55-60.

REFERENCES 401-406.

1. Heit JA. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism.

Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(8):464-474.

jama.com (Reprinted) JAMA May 16, 2017 Volume 317, Number 19 2009

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/jama/936236/ by Roberto Lopez Mata on 05/17/2017

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Discrete Mathematics Sets Relations FunctionsDocument15 pagesDiscrete Mathematics Sets Relations FunctionsMuhd FarisNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Norman Perrin-What Is Redaction CriticismDocument96 pagesNorman Perrin-What Is Redaction Criticismoasis115100% (1)

- Planetary DescriptionsDocument6 pagesPlanetary DescriptionsshellymaryaNo ratings yet

- Black-Scholes Excel Formulas and How To Create A Simple Option Pricing Spreadsheet - MacroptionDocument8 pagesBlack-Scholes Excel Formulas and How To Create A Simple Option Pricing Spreadsheet - MacroptionDickson phiriNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Septic ShockDocument19 pagesPathophysiology of Septic ShockRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Build Web Application With Golang enDocument327 pagesBuild Web Application With Golang enAditya SinghNo ratings yet

- HTN Emergencies and UrgenciesDocument14 pagesHTN Emergencies and UrgenciesRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Synopsis of The 2017 American College of Cardiology:American Heart Association Hypertension GuidelineDocument10 pagesPrevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Synopsis of The 2017 American College of Cardiology:American Heart Association Hypertension GuidelineRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Myths Regarding The Diagnosis and Treatment of CellulitisDocument8 pagesTop 10 Myths Regarding The Diagnosis and Treatment of CellulitisRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Hyperglycemic CrisisDocument9 pagesHyperglycemic CrisisRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- ADA 2018 Diabetes CareDocument150 pagesADA 2018 Diabetes CareRoberto López Mata100% (1)

- 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway For Optimization of Heart Failure TreatmentDocument30 pages2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway For Optimization of Heart Failure TreatmentRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Uric Acid Is A Strong Risk Marker For Developing Hypertension From PrehypertensionDocument16 pagesUric Acid Is A Strong Risk Marker For Developing Hypertension From PrehypertensionRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Best Clinical Practice: AnaphylaxisDocument6 pagesBest Clinical Practice: AnaphylaxisputriNo ratings yet

- Update On The Management of Venous ThromboembolismDocument8 pagesUpdate On The Management of Venous ThromboembolismRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment of HyperkalemiaDocument9 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment of HyperkalemiaRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Effects of Acarbose On Cardiovascular and Diabetes Outcomes in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease and Impaired Glucose Tolerance (ACE) - A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled TrialDocument10 pagesEffects of Acarbose On Cardiovascular and Diabetes Outcomes in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease and Impaired Glucose Tolerance (ACE) - A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled TrialRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Necrotizing Soft-Tissue InfectionsDocument13 pagesNecrotizing Soft-Tissue InfectionsRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Fluid Therapy Options and Rational SelectionDocument13 pagesFluid Therapy Options and Rational SelectionRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- The Role of Nitroglycerin and Other Nitrogen Oxides in Cardiovascular TherapeuticsDocument18 pagesThe Role of Nitroglycerin and Other Nitrogen Oxides in Cardiovascular TherapeuticsRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis B Vaccination, Screening, and Linkage To Care - Best Practice Advice From The American College of Physicians and The Centers For Disease Control and PreventionDocument12 pagesHepatitis B Vaccination, Screening, and Linkage To Care - Best Practice Advice From The American College of Physicians and The Centers For Disease Control and PreventionRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- The Use of Cephalosporins in Penicillin-Allergic Patients - A Literature ReviewDocument9 pagesThe Use of Cephalosporins in Penicillin-Allergic Patients - A Literature ReviewRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- The Dark Sides of Fuid Administration in The Critically Ill PatientDocument3 pagesThe Dark Sides of Fuid Administration in The Critically Ill PatientRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Diuretic Treatment in Heart FailureDocument12 pagesDiuretic Treatment in Heart FailureRoberto López Mata100% (1)

- Sudden Cardiac Arrest During Participation in Competitive SportsDocument11 pagesSudden Cardiac Arrest During Participation in Competitive SportsRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Rivaroxaban Vs Warfarin Sodium in The Ultra-Early Period After Atrial Fibrillation-Related Mild Ischemic StrokeDocument10 pagesRivaroxaban Vs Warfarin Sodium in The Ultra-Early Period After Atrial Fibrillation-Related Mild Ischemic StrokeRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- 2015 ESC Guidelines For The Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial DiseasesDocument44 pages2015 ESC Guidelines For The Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial DiseasesRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Atrial Fibrillation and HypertensionDocument17 pagesAtrial Fibrillation and HypertensionRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- A Test in Context - D-DimerDocument10 pagesA Test in Context - D-DimerRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Synopsis of The 2017 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: Management of Type 2 Diabetes MellitusDocument10 pagesSynopsis of The 2017 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: Management of Type 2 Diabetes MellitusRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Effects on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events of the Addition of Pioglitazone Versus Sulfonylureas in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Inadequately Controlled With Metformin (TOSCA.it)- A Randomised, Multicentre TrialDocument11 pagesEffects on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events of the Addition of Pioglitazone Versus Sulfonylureas in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Inadequately Controlled With Metformin (TOSCA.it)- A Randomised, Multicentre TrialRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Dual Antithrombotic Therapy With Dabigatran After PCI in Atrial FibrillationDocument12 pagesDual Antithrombotic Therapy With Dabigatran After PCI in Atrial FibrillationRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Acute Monocular Vision LossDocument9 pagesAcute Monocular Vision LossRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Evaluation and Management of Lower-Extremity UlcersDocument9 pagesEvaluation and Management of Lower-Extremity UlcersRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Verification ofDocument14 pagesVerification ofsamuel-kor-kee-hao-1919No ratings yet

- Andrew Haywood CV 2010Document6 pagesAndrew Haywood CV 2010Dobber0No ratings yet

- E-WasteDocument18 pagesE-WasteNitinKotwarNo ratings yet

- Sample PREP-31 Standard Sample Preparation Package For Rock and Drill SamplesDocument1 pageSample PREP-31 Standard Sample Preparation Package For Rock and Drill SampleshNo ratings yet

- It'S Not A Lie If You Believe It: LyingDocument2 pagesIt'S Not A Lie If You Believe It: LyingNoel ll SorianoNo ratings yet

- 14-) NonLinear Analysis of A Cantilever Beam PDFDocument7 pages14-) NonLinear Analysis of A Cantilever Beam PDFscs1720No ratings yet

- Advanced Signal Multi-ScannerDocument8 pagesAdvanced Signal Multi-ScannerneerajupmanyuNo ratings yet

- NationalMootCourtCompetition Moot ProblemDocument5 pagesNationalMootCourtCompetition Moot ProblemKarsin ManochaNo ratings yet

- Reformer Tube Inspection: Leo - ScanDocument5 pagesReformer Tube Inspection: Leo - ScanAnonymous 5odj1IcNo ratings yet

- Effects of Temperature and Moisture On SMCDocument20 pagesEffects of Temperature and Moisture On SMCsenencostasNo ratings yet

- Botbee IntegrationDocument16 pagesBotbee IntegrationAnuj VikalNo ratings yet

- Microelectronic CircuitsDocument22 pagesMicroelectronic CircuitsarunnellurNo ratings yet

- Qualifications Recruitment Promotions Scheme - University AcademicsDocument10 pagesQualifications Recruitment Promotions Scheme - University Academicsuteachers_slNo ratings yet

- Alpha-Qwerty Cipher: An Extended Vigenere CipherDocument12 pagesAlpha-Qwerty Cipher: An Extended Vigenere CipherAnonymous IlrQK9HuNo ratings yet

- MCVM: Monte Carlo Modeling of Photon Migration in Voxelized MediaDocument12 pagesMCVM: Monte Carlo Modeling of Photon Migration in Voxelized MediaĐô Lê PhiNo ratings yet

- Binary RelationDocument9 pagesBinary RelationDavidNo ratings yet

- Jillin ExplosionDocument10 pagesJillin ExplosionArjun ManojNo ratings yet

- Scheme of Work Writing Baby First TermDocument12 pagesScheme of Work Writing Baby First TermEmmy Senior Lucky100% (1)

- Mexico For Sale. Rafael GuerreroDocument12 pagesMexico For Sale. Rafael GuerreroGabriela Durán ValisNo ratings yet

- DfgtyhDocument4 pagesDfgtyhAditya MakkarNo ratings yet

- 4D Asp: Wall Tiling 4D - PG 1Document3 pages4D Asp: Wall Tiling 4D - PG 1Vlaho AlamatNo ratings yet

- Academics: Qualification Institute Board/University Year %/CGPADocument1 pageAcademics: Qualification Institute Board/University Year %/CGPARajesh KandhwayNo ratings yet

- Role of ICT & Challenges in Disaster ManagementDocument13 pagesRole of ICT & Challenges in Disaster ManagementMohammad Ali100% (3)

- Name: Period: Date:: Math Lab: Explore Transformations of Trig Functions Explore Vertical DisplacementDocument7 pagesName: Period: Date:: Math Lab: Explore Transformations of Trig Functions Explore Vertical DisplacementShaaminiNo ratings yet

- Nexlinx Corporate Profile-2019Document22 pagesNexlinx Corporate Profile-2019sid202pkNo ratings yet