Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BLFS Part1

Uploaded by

chrmerzOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BLFS Part1

Uploaded by

chrmerzCopyright:

Available Formats

Part 1: The Lean Fulfillment Stream

What is a Fulfillment Stream?

In todays world, most products move across many companies and through many

departments within each company on their way to the final customer. Because the

movement of material is so complex, businesses struggle to understand the progression

of their products as they move from their suppliers through their own organization into

distribution and on to the customer. Certainly work is done by others somewhere, but

managers in each firm and facility are often unaware who does what, where, and when

beyond their receiving and shipping docks. And many dont want to think about it.

Businesses have traditionally referred to the progression of materials from suppliers

to end customers as the supply chain. But a chain suggests something heavy and

inflexible, prone to kinking and jamming. Its static rather than dynamic. Within

a chain its easy for managers to lose sight of the flow of value from start to finish.

Instead they focus on optimizing the one link they control, whether its a process,

a department, or even an entire firm.

To capture the lean concept of smooth flow, we find it helpful to envision a steadily

advancing stream of materials and the firms and facilities involved as tributaries joining

their efforts to serve the customer. We call this flow of parts and finished products a

fulfillment stream. It includes all of the activities that move materials and information

from suppliers to end customers: planning, sourcing, transporting, manufacturing,

inspecting, storing, packing, and consuming, as well as managing the entire process.

Once managers understand that they are involved in a fulfillment stream, we find

that they can identify the obstacles preventing the stream from flowing smoothly and

swiftly. But because no single manager or firm controls the entire stream, new forms

of collaboration are necessary to reduce the total cost of the stream while improving

its responsiveness to customer needs. To understand how this can happen we will

follow in this workbook the experience of a sample company as it learns to focus

on its end-to-end fulfillment stream to make it lean.

Part 1: The Lean Fulfillment Stream 1

Welcome to ABE Corp.

ABE is a privately owned, mid-sized manufacturer of commercial and residential air

conditioning units that are sold through distributors. Even though ABE makes only a

moderate range of products, its fulfillment stream from raw materials to customers is

lengthy and complex: 160 suppliers ship materials to ABE using 37 different carriers.

These materials are assembled in two factories into 40 different completed products.

Finished goods are sent to three regional distribution centers via six different carriers.

Items are then shipped to 10 national wholesalers using 17 additional carriers.

In recent years, ABE responded to demands from its customers for lower prices, higher

quality, and more rapid response by implementing lean manufacturing processes. It

improved the stability of its production equipment, created high-performance work

cells for product families to replace process villages, and reduced batch sizes. The

results of these classic lean production initiatives were dramatic, and ABE was able

to maintain profit margins while reducing prices.

But then customers demanded further price reductions, still higher quality, and even

more responsiveness. Prices dropped and sales stagnated. Earnings before interest and

taxes (EBIT) fell to practically zero. Some of the companys board members urged

ABE executives to cut costs by relocating production to lower-wage countries, despite

longer distances and lead times.

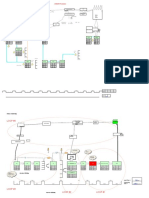

ABE Operations at a Glance

Suppliers Inbound Plants, shipping,

logistics and receiving yard

Suppliers Seattle Indianapolis

Suppliers = 160 Truckload carriers = 15 Plants = 2

- Domestic = 150 Less-than-truckload Employees = 1,100

- International = 10 carriers = 15 Raw-material inventory = $25 million

Material spend = $150 million Courier providers = 3 WIP inventory = $10 million

Number of purchased Ocean carriers = 4 Finished-goods inventory = $61 million

parts = 1,000

Inbound transportation Finished-goods SKUs = 40

costs = $5 million

2 Building a Lean Fulfillment Stream

The CFO estimated that to remain competitive, ABE needed to reduce overall costs by

$20 million within two years at constant sales. (ABEs financial situation is shown in its

income statement and balance sheet on page 4).

When ABEs senior managers met to discuss the situation, they reflected on their process

of lean improvements in the preceding years. They had used strategy deployment to

prioritize the most important needs of the business and set objectives. They achieved

these objectives using A3 analysis and the classic Deming method of plan, do, check,

act (PDCA). This allowed creative thinking and problem-solving to flourish in the

company, while it maintained and improved process discipline. Given past successes,

they easily agreed that this approach should be applied to the CFOs objective.

The management team felt that they had implemented lean techniques in the factories

to such a degree that a further leap in performance equal to the new challenge wasnt

feasible. They also felt that pushing the cost problem back on suppliersas many of

their competitors had donewould provide only temporary relief while jeopardizing

the stability of their supply base.

Fortunately, several members of the management team were familiar with the concept of

the lean fulfillment stream from experiences supplying other lean firms. They suggested

that the most promising way to reduce costs to meet the CFOs target within two years

was to tackle the total cost of fulfillment.

Outbound Regional Outbound Customer

logistics distribution logistics

intercompany center

Regional Customer

distribution

center

Truckload carriers = 6 Regional DCs = 3 Truckload carriers = 12 Customers = 10

Intercompany transportation (Chicago, Atlanta, Dallas) Less-than-truckload Total sales = $250 million

costs = $5 million Finished-goods carriers = 5 Ship-to locations = 120

inventory = $6.25 million Outbound transportation

Total space = 250,000 sq. ft. spend = $12.5 million

Part 1: The Lean Fulfillment Stream 3

ABE Income Statement

Revenue Current Year % of Sales

Sales $250,000,000 100.0%

Cost of goods sold (COGS)

Material purchases $150,000,000 60.0%

Inbound transportation $5,000,000 2.0%

Conversion costs $50,000,000 20.0%

Subtotal: COGS $205,000,000

Operating Profit $45,000,000 18.0%

Operating expenses

Product development $1,000,000 0.4%

Outbound and intercompany transportation $17,500,000 7.0%

Distribution center management $5,000,000 2.0%

Selling, general and administrative $17,500,000 7.0%

Interest (line of credit) $1,500,000 0.6%

Subtotal: Operating expenses $42,500,000 17.0%

Earnings before income taxes (EBIT) $2,500,000 1.0%

ABE Balance Sheet

Assets Current

Cash $2,000,000

Accounts receivable $42,000,000

Raw materials inventory $25,000,000

Work-in process inventory $10,000,000

Finished-goods inventory $61,000,000

Total current assets $140,000,000

Fixed assets $20,000,000

Total assets $160,000,000

Liabilities and shareholders equity

Accounts payables $50,000,000

Short-term debt (line of credit) $20,000,000

Total current liabilities $70,000,000

Long-term debt $30,000,000

Total liabilities $100,000,000

Owners equity $60,000,000

Total liability and owners equity $160,000,000

4 Building a Lean Fulfillment Stream

Total Cost of Fulfillment

The total cost of fulfillment is all of the costs of moving materials from one end of

the fulfillment stream to the other. These go far beyond the transportation costs most

firms calculate to include the carrying and storage costs of inventory, the cost of

material handling equipment and labor, and the management time devoted to gathering

all of the information needed to constantly monitor performance. These costs also

include all of the transport, inventory, handling, and management costs incurred by

customers and suppliers along the fulfillment stream. The senior managers of every

firm in the stream would find the total cost surprisingly large once summed.

When the ABE management team committed to reducing the total cost of fulfillment,

they realized that this would be an entirely new way of thinking for their suppliers,

customers, and ABEs lower-level managers. The latter had gained an ability to see

the value stream within their own facilities as a result of previous lean initiatives.

But they had never learned to see the entire fulfillment stream and had no idea of the

impact of the streams performance on ABEs financial performance. Their natural

reaction was to ask, What difference does it make what the total cost is? Why cant

I focus on controlling costs within my own department? Suppliers and customers

would feel the same way.

In considering how to proceed, ABEs senior managers reflected on their experiences

implementing lean techniques in ABE operations. The most successful teams had

performed cohesively to achieve collective goals, and took into consideration how

their actions affected other teams and departments. These collaborative skills, when

set in the context of the financial needs of the whole business, produced the best

results. Extending this concept to the lean fulfillment stream would mean looking

jointly at the whole stream to achieve maximum value for customers and suppliers

at lowest costs while sharing the benefits.

ABE managers realized that for a shift to a lean fulfillment-stream perspective to be

successful, all departments and companies involved needed to embrace two core beliefs:

The customer at the end of the fulfillment stream must define value, and

their rate of consumption must set the pace for the entire stream. Doing

this requires managing the entire process as a lean fulfillment stream.

Costs must be managed jointly over the long-term, with a clear

understanding of how decisions at different points affect the entire

fulfillment stream, in order to minimize the total cost of fulfillment.

Part 1: The Lean Fulfillment Stream 5

The Fulfillment-Stream Council

ABEs managers decided that for the fulfillment-stream participants to work as an

effective team an organizational innovation would be needed. They formed a Fulfillment-

Stream Council comprised of a senior leader from each functional area of ABE (Finance,

Operations, Purchasing, etc.) plus representatives from suppliers and customers.

ABE appointed internal members to the Fulfillment-Stream Council, and then enlisted

its suppliers and customers to do likewise. The members were expected to serve for

an extended period (typically two years, with a minimum of one year and a maximum

of three) until the transformation to a lean fulfillment stream was in place, meeting

quarterly to review progress.

The council would provide vision and leadership for the transformation, but it would

not make day-to-day decisions. Instead it would create awareness of benefits of a

fulfillment-stream focus, research issues, and challenge business decisions that run

counter to fulfillment-stream thinking.

The Fulfillment-Stream Council was responsible for:

Developing, communicating, and promoting guiding principles for managers

along the fulfillment stream.

Examining business decisions from a total cost of fulfillment perspective.

Identifying and eliminating barriers to total cost of fulfillment thinking.

The Fulfillment-Stream Council needed to answer the following question: What is

the correct way to run the business in order to minimize total cost? To answer this

question the council needed to agree on some simple guiding principles.

Guiding Principles

Why does fulfillment-stream management require guiding principles? Because a

fulfillment stream is lengthy and dynamic and its impossible for managers to evaluate

every action taken with detailed analysis. For example, Toyota has a guiding principle

that reducing lead time is the right thing to do. Managers there dont spend time doing

analysis every time they try to reduce lead time to prove that this is the correct thing

to do. Instead they live by the guiding principle, confirmed over several decades, that

reducing lead time eliminates waste, improves quality, and reduces costs.

6 Building a Lean Fulfillment Stream

Eight guiding principles have been shown over many years to be essential for creating

lean fulfillment streams:

1. Eliminate all the waste in the fulfillment stream so that only value remains.

Creating flow in a fulfillment stream requires all departments and functions in an

organization to work in harmony. Focusing on the fundamental lean principle of

eliminating waste so that only value remains helps achieve this harmony.

The seven types of waste in manufacturing are well known: overproduction, waiting,

conveyance, processing, inventory, motion, and correction. The seven types of waste

for fulfillment streams are:

System complexityelaborate scheduling systems and managers working

around mismatches between the formal schedule and actual needs.

Lead timetoo much time from one step to the next.

Transportexcessive conveyance among facilities and companies.

Spacein lieu of processing, space becomes a value factor and excessive

space for storing inventories is waste.

Inventoryat any point in the fulfillment stream.

Human effortfulfillment-stream members working at cross-purposes,

which creates rework, confusion, and excessive motion.

Packagingthe wrong types of goods in the wrong quantities resulting

in damages, excessive inventories, and corrections downstream.

2. Make customer consumption visible to all members of the fulfillment stream.

If customer consumption is visible across the entire fulfillment stream, then it is much

easier for every participant to plan work based on the pull of customer demand.

3. Reduce lead time.

Reducing inbound and outbound logistics lead times will get orders to the customer

faster. When a company can reduce lead times to the point where it can exceed lead-

time expectations of the customer, it will no longer need to rely on forecasts and can

pull material throughout the fulfillment stream. End-to-end fulfillment-stream lead

times are reduced when overall inventory in the system is reduced.

Part 1: The Lean Fulfillment Stream 7

4. Create level flow.

The ultimate goal is to have goods and information move in a predictable, consistent,

and uninterrupted manner based on the actual demand of the customer. This is known

as level flow. Level flow reduces variation in processes and tries to spread activities

equally over working time. This minimizes the peaks and valleys in movement that

create unevenness and overburden, which result in waste.

5. Use pull systems.

Use pull systems when level flow is not possible. A pull system is an inventory-

replenishment method (i.e., kanban) in which each downstream activity (customer

consumption) signals its need to the next upstream activity. Pull systems reduce

wasteful complexity in planning and overproduction that can occur with computer-

based software programs such as material resource planning (MRP), and they permit

visual control of the flow of materials in the fulfillment stream.

6. Increase velocity and reduce variation.

Velocity is the speed with which information and material move through the fulfillment

stream. Meeting customer demand by delivering smaller shipments more frequently

increases velocity. This helps to reduce inventories and lead times, which allows you

to more easily adjust delivery to meet actual customer consumption.

7. Collaborate and use process discipline.

The collaboration of all participants in a fulfillment stream is necessary to identify

problems in the stream, determine root causes, and develop appropriate countermeasures.

To be truly effective, this collaboration must be combined with standard improvement

processes and regular PDCA.

8. Focus on total cost of fulfillment.

Make decisions that will meet customer expectations at the lowest possible total cost

no matter where they occur in the fulfillment stream. This means eliminating decisions

that benefit one part of the stream at the expense of others. This is the real challenge

of building a lean fulfillment stream, but it can be achieved when all members share

in the operational and financial benefits when waste is eliminated.

8 Building a Lean Fulfillment Stream

River of Waste

Picture your organization (and your fulfillment stream) as a ship navigating

down a river. The river represents your business environmentflowing fast

with rocks below the water that can puncture the hull. The rocks are problems

and wastes (excessive inventories, transport, space, time, packaging, work, and

rework) and the water level is inventory throughout the fulfillment stream that

hides the rocks.

As you flow down the river, you can do one of three things:

Navigate around the rocks, relying on managers to constantly change

course (firefighting).

Raise the water level (inventory) to float freely over of the rocks.

Expose and eliminate the rocks permanently, so the ship can sail safely

and with less water (inventory) to its destination (your customers).

Managers often raise inventory levels or keep them unnecessarily high because:

Supplier deliveries are unreliable, so they add safety stock to gain

a sense of security.

Transportation lead times are erratic, so they add buffer stocks in

order to cover variability in lead times.

Companywide teamwork is lacking, so they build up inventories

between departments to protect against the perceived incompetence

of departments.

Communication with customers is lacking, so they hedge against demand

uncertainties and raise finished-goods inventory levels.

Inventory only hides these problems. Your company can continue to ignore

problems and waste (rocks below the water) and raise the water level (inventory).

But eventually excessive inventory will result in a highly inefficient company

with uncontrolled internal costs (a boat out of control and thrown over the

rivers edge by high water). The goal is to gradually create a river that is calm

and navigable, removing water slowly to expose rocks without hitting them, and

then address each rock (problem) with lean tools to remove them permanently.

Part 1: The Lean Fulfillment Stream 9

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Agile Kanban BoardDocument10 pagesAgile Kanban BoardAjay SimonNo ratings yet

- Addition and Subtraction: StudentDocument45 pagesAddition and Subtraction: StudentKhaing PhyuNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Trillion Dollar CoachDocument36 pagesTrillion Dollar CoachJay Bhatt92% (12)

- GMP Auditor TrainingDocument93 pagesGMP Auditor TrainingNikka LopezNo ratings yet

- Training GMP SlideshowDocument28 pagesTraining GMP SlideshowJoshua JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Lean Leadership PowerPoint PresentationDocument83 pagesLean Leadership PowerPoint PresentationchrmerzNo ratings yet

- Trade Fair: by Dr. Swati YadavDocument24 pagesTrade Fair: by Dr. Swati YadavSwati YadavNo ratings yet

- Goals: Hoshin StrategiesDocument12 pagesGoals: Hoshin StrategiesSubhangkar BanikNo ratings yet

- Urban Design - PPT 1Document10 pagesUrban Design - PPT 1Gaurav bajaj80% (5)

- Design For Manufacturing and Assembly: Prepared By-Prashant TripathiDocument44 pagesDesign For Manufacturing and Assembly: Prepared By-Prashant Tripathichrmerz100% (1)

- Why Logic Builds AgreementDocument4 pagesWhy Logic Builds AgreementchrmerzNo ratings yet

- 12 Habits Of Highly Collaborative OrganizationsDocument6 pages12 Habits Of Highly Collaborative OrganizationschrmerzNo ratings yet

- The Coaching Cycle Is Not A JudgementDocument2 pagesThe Coaching Cycle Is Not A JudgementchrmerzNo ratings yet

- ZANGEN Produktion 0001Document5 pagesZANGEN Produktion 0001chrmerzNo ratings yet

- ZANGEN Produktion 0001Document5 pagesZANGEN Produktion 0001chrmerzNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Questions: Why Are You Asking Questions?Document3 pagesDiagnostic Questions: Why Are You Asking Questions?chrmerzNo ratings yet

- Supply Chains: To Build Resilience, Manage ProactivelyDocument7 pagesSupply Chains: To Build Resilience, Manage ProactivelychrmerzNo ratings yet

- Kaizen Event Charter Template for Process ImprovementDocument1 pageKaizen Event Charter Template for Process ImprovementchrmerzNo ratings yet

- Unlocking Enterprise Efficiencies Through Zero-Based DesignDocument8 pagesUnlocking Enterprise Efficiencies Through Zero-Based DesignchrmerzNo ratings yet

- ZANGEN Produktion 0001Document5 pagesZANGEN Produktion 0001chrmerzNo ratings yet

- InstantGMP Trainers Orientation Slides v3.000Document48 pagesInstantGMP Trainers Orientation Slides v3.000chrmerzNo ratings yet

- Strategic Doing: An Introductory WorkshopDocument75 pagesStrategic Doing: An Introductory WorkshopchrmerzNo ratings yet

- GMP PartiDocument21 pagesGMP PartichrmerzNo ratings yet

- A Leaner Public SectorDocument7 pagesA Leaner Public SectorchrmerzNo ratings yet

- Smit Patel: Quality ExecutiveDocument22 pagesSmit Patel: Quality ExecutivechrmerzNo ratings yet

- Gemba WalkDocument1 pageGemba WalkchrmerzNo ratings yet

- McKinsey China Job Opening - Mandarin SpeakerDocument1 pageMcKinsey China Job Opening - Mandarin SpeakerchrmerzNo ratings yet

- Method Target Objective PROCESS Target Objective FINANCE Criteria 1 Criteria 2 Criteria 3 TrainingDocument1 pageMethod Target Objective PROCESS Target Objective FINANCE Criteria 1 Criteria 2 Criteria 3 TrainingchrmerzNo ratings yet

- Mini TabDocument54 pagesMini TabchrmerzNo ratings yet

- Bata Black ShoeDocument1 pageBata Black ShoeGaurav ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Rajnikant Makwana - MISDocument3 pagesRajnikant Makwana - MISRajnikant MakwanaNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On HRDDocument51 pagesA Project Report On HRDMuskan TanwarNo ratings yet

- Xola's Curriculum VitaeDocument2 pagesXola's Curriculum VitaeqhogwanaNo ratings yet

- Bank Nov22Document7 pagesBank Nov22Diviyan MacNo ratings yet

- Economy Gets New Anti-Viral Shot: Big Spike Again, 44 New Cases in K'takaDocument16 pagesEconomy Gets New Anti-Viral Shot: Big Spike Again, 44 New Cases in K'takaShaik RuksanaNo ratings yet

- Assignment of International BusinessDocument6 pagesAssignment of International BusinessNikunj GevariyaNo ratings yet

- Example Cover Letter For Internal Job PostingDocument5 pagesExample Cover Letter For Internal Job Postingtbrhhhsmd100% (1)

- Business Incubation Training ProgramDocument10 pagesBusiness Incubation Training ProgramJeji HirboraNo ratings yet

- Research Report-Competition Assessment of Payments Infra in IndiaDocument61 pagesResearch Report-Competition Assessment of Payments Infra in IndiaFerdosa FernandezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 (Slides)Document35 pagesChapter 2 (Slides)Beibei LingNo ratings yet

- Swot Analysis of Demat Account Services Reliance SecuritiesDocument53 pagesSwot Analysis of Demat Account Services Reliance SecuritiesSumit Kumar67% (3)

- Midterm Principles LSCM 2021-2022Document4 pagesMidterm Principles LSCM 2021-2022Ngo HieuNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary: Sources and Application of FundsDocument6 pagesExecutive Summary: Sources and Application of FundsJimmy DagupanNo ratings yet

- Radiologic Technologists Socio-Demographic ProfileDocument2 pagesRadiologic Technologists Socio-Demographic ProfileIluminadaNo ratings yet

- Did You Know?: Date HeadquartersDocument3 pagesDid You Know?: Date HeadquartersAlaina AghaNo ratings yet

- Tax InvoiceDocument1 pageTax InvoiceSunny SinghNo ratings yet

- Negros Oriental State University: Brett ClydeDocument4 pagesNegros Oriental State University: Brett ClydeCORNADO, MERIJOY G.No ratings yet

- 5 Konsep Inti Konsumen Dan Pasar Di Era DigitalDocument16 pages5 Konsep Inti Konsumen Dan Pasar Di Era DigitalSatria SeptuNo ratings yet

- COMSATS Internship Report FormatDocument4 pagesCOMSATS Internship Report FormatMuhammad Muavia Khan50% (2)

- CFA-FRA-R15-26-updated 0110122Document532 pagesCFA-FRA-R15-26-updated 0110122Trang NgôNo ratings yet

- Economics Chapter 1Document31 pagesEconomics Chapter 1Nyigol BielNo ratings yet

- OPTV003620Document2 pagesOPTV003620Rahul PatelNo ratings yet

- Test 1 Chap 1-4 FNAN 4030Document32 pagesTest 1 Chap 1-4 FNAN 4030Sheena CabNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1 Course of Action and RecommendationDocument5 pagesCase Study 1 Course of Action and Recommendationronniel tiglaoNo ratings yet

- TDS Alcomer 90PDocument2 pagesTDS Alcomer 90PPrototypeNo ratings yet

- PDF - Learn More - Capital Gains - Problems and SolutionsDocument5 pagesPDF - Learn More - Capital Gains - Problems and Solutionsbsc slpNo ratings yet