Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Political Ecology of Water Conflicts

Uploaded by

pierdayvientoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Political Ecology of Water Conflicts

Uploaded by

pierdayvientoCopyright:

Available Formats

Advanced Review

Political ecology of water conicts

Beatriz Rodrguez-Labajos and Joan Martnez-Alier

This article reviews methodologies, types, and political implications of water

conicts from a political ecology perspective. The political ecology of water studies

the conicts on water use, whether as an input or as a vehicle for waste disposal.

Both the quantity and the quality of water are relevant for conicts on water as

a commodity and also indirectly in conicts on water from oil and gas extraction,

mining, or biomass production. This study provides an overview and classication

of water conicts, showing how social movements born from such conicts are

creatively generating new modalities of water management and governance in

the process. To this end, this article rst examines methodological approaches

for the analysis of water conicts and water justice. Then, a taxonomy of water

conicts based on the stages of the commodity chain is presented and discussed.

Afterward, empirical evidence is collected showing how social mobilizations

in water conicts become effective providers of management alternatives and

governance modalities. Water justice movements and organizations have formed

networks, have proposed new principles of water management, and have not only

been active in the promotion of the human right to water but also in the recognition

of water, along with other elements of nature, as a subject of rights. 2015 Wiley

Periodicals, Inc.

How to cite this article:

WIREs Water 2015, 2:537558. doi: 10.1002/wat2.1092

INTRODUCTION agency, water accumulates polluting substances and

organismsmaking it unavailable for some human

T here is a hydrological cycle, which would also

exist if there were no humans.1 Driven by sun

energy, this cycle has a fundamental importance in

usesuntil it reaches its maximum level of entropy

on reaching the sea.6 Then, solar radiation returns

water to the clouds and the cycle continues sustainably

the regulation of climate and on life in the planet.2 although the global entropy production may have

Yet human agency has come to shape the circulation grown.7

of water, through canals and dams, with abstractions Of course, natural water pollution occurs

for irrigation and drinking water, and modifying the sometimes, as in the case of bedrock formations that

chemical, biological, and morphological properties of contain arsenic.8,9 Regularly, although, when a mining

the watercourses for the benefit of some sectors of the company or urban populations use water to evacuate

population, and to the detriment of others. This is the waste, the quality goes down. Therefore, it cannot be

hydrosocial cycle.3,4 used in other applications such as irrigation in agricul-

Humans require certain amounts of water of ture unless its quality is enhanced again through costly

different quality (e.g., for drinking, agriculture, or water treatments. Changes in quality maybe related to

to cool thermoelectric power stations). Following human-induced chemical pollution,10 thermal,11,12 or

Naredo (Ref 5, p. 14), the gradient of the water microbiological pollution.13 There is also the concept

quality tends to decrease as it becomes available as of biopollution to refer to damaging alien species

rain or snow until it reaches the sea. Through human introduced in aquatic ecosystems as an outcome of

human action.14,15

Correspondence to: labajos_bea@yahoo.com Historically, water management systems are

Institute of Environmental Science and Technology, Autonomous designed to influence the hydrosocial cycles by

University of Barcelona (ICTA-UAB), Cerdanyola del Valls, Spain reshaping the river basin waterscapes.1619 The

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest search for adequate quantity and quality of water has

for this article. motivated the construction of wells and cisterns to

Volume 2, September/October 2015 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 537

Advanced Review wires.wiley.com/water

collect rainwater for domestic use in areas of brackish to other species.27,28 The focus of political ecol-

groundwater and scarce surface water.20 It has also ogy is on how the costs and benefits associated

motivated interbasin transfers of water19,21,22 and with environmental change are unevenly distributed

investmentsin money and energyto obtain fresh among humans. For instance, women are particularly

water through desalination plants.23,24 exposed to tensions related with (safe) water access

The reshaping of the hydrosocial cyclealways and unequal distribution of labor, and emotional man-

embedded in historical and sociocultural agement costs.9 Another angle is to understand how

contexts25 generates both positive and negative a reduction of inequalities of gender, caste, race, or

effects for different types of actors, who therefore social class empowers the unprivileged, and changes

perceive such changes differently. From this, socioen- ecological distribution.27

vironmental conflicts about water management arise. There are two main styles of political ecology

In general, ecological distribution conflicts are studied (Ref 26, p. 256). The first combines human ecol-

by political ecology, a field created by geographers, ogy (mainly, the analysis of the social metabolism)

anthropologists, and environmental sociologists.26 with social and political analysis, i.e., how different

In this article, we study the political ecology social actors at different scales contest the claims of

of water, focusing on the connection between water other actors to resources in a particularly ecologi-

conflicts and water-based activism, which has not cal context.29 Examples of this view would be stud-

been given much attention in scientific literature. ies focusing on inequitable and unsustainable water

Therefore, the main rationale behind this article is distribution30 ; or the critical role of politics in the

bringing together the literatures on political ecology, maintenance of water metabolism.31

water justice studies, and ecological distribution con- However, apart from empirical unequal uses and

flicts. While systematicallya examining the interplay practices, there is a political ecology that also consid-

between the above fields, a key concern has been to ers the construction of environmental or water knowl-

highlight novelty, without neglecting well-established edge (and the role of science and policy herein), and

assertions in each field. The review aims at being an the battle of water-based subjectivities,32 narratives,33

entry point to the study of water conflicts for politi- and epistemologies.34 This second style centres more

cal ecologists, and for water researchers from different on the different interpretations of natural or techni-

disciplines who search clarification on the use of polit- cal facts (such as the meanings of water scarcity35 or

ical ecology terms and approaches, particularly with water security36 ).

application to bottomup water governance. As an It is clear that the political ecology of water

additional value added, the study brings to a broader has a hybrid character where biophysical and soci-

audience contributions from a fertile Hispanophone etal explanations are deeply intertwined.37 Because

literature on water justice studies and activism. of the inescapability from material constraints in sus-

In particular, our aim is to provide an overview tainability debates3840 and because of the poten-

and classification of water conflicts, showing how tial of such materiality to facilitate multidisciplinary

social movements are creatively trying to solve or deal debates,41,42 this article tends to be written in the first

with themgenerating new modalities of water man- style. Even though we acknowledge that in field or

agement and governance in the process. To this end, factory, in ghetto or grazing ground, struggles over

this article first examines methodological approaches resources [or over pollution] have always been strug-

for the analysis of water conflicts. Then, examples gles over meanings (Ref 43, p. 13).

are discussed introducing a taxonomy of water con- The simultaneous natural and social ontologies

flicts based on the stages of the commodity chain. A of water25,44 are pertinent for the notion of water

section follows on social mobilizations in water con- justice of hydric justice. This can be considered as

flicts as effective providers of management alternatives an application of the wider notion of environmen-

and governance modalities. Conclusions are drawn in tal justice (EJ) that arose in the early 1980s in the

the final section. United States from the inequity in the distribution

of environmental risk among different social seg-

POLITICAL ECOLOGY AND WATER ments of society.45 The definition expanded to encom-

pass the recognition of representation of the social

JUSTICE actors involved, and the guarantees for their effective

Political ecology studies how the distribution of participation.46,47 In the last decades, the EJ discourse

power (which is the main subject of political sci- has grown geographically, horizontally across a broad

ence) determines the use of the natural environ- range of issues, vertically in the global nature of injus-

ment between categories of humans and with regard tices, and conceptually in relation with the nonhuman

538 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Volume 2, September/October 2015

WIREs Water Political ecology of water conicts

world.48,49 The new movements for water justice or languages that rely on alternative rationalities, e.g., in

hydric justice, born from local conflicts and struggles terms of indigenous territorial rights, livelihood val-

on water, are part of the world movements for EJ. ues, or sacredness.

From their standpoint, water runs in the direction of From a political ecology perspective, there are

power or (at the same time) towards money.50 multiple ways in which impacts (or external costs) are

created and affect particular groups, e.g., water short-

age, floods, and pollution.19 The MCE approach arose

METHODS AND APPROACHES FOR against CBA. It enables a plural account of the eco-

THE ANALYSIS OF WATER CONFLICTS logical functions of water in the ecosystems and their

associated values, which are not readily measurable in

Political power appears in political ecology on two money terms or in any other single unit. MCE meth-

levels: first, the power to impose a decision by rea- ods help to structure social-choice problems involving

son or by force; and second, the power to impose a ecological, social, political, and economic objectives

procedure that legitimizes the decision, including pro- in conflict, considering various interest groups and dif-

cesses of knowledge generation. Thus, naked power ferent valuation languages.55 Technical MCE are help-

can impose a decision on building a dam because of ful to explore policy options and constraints in cases

the rulers will, while procedural power will consist in where water conflicts have been exacerbated by public

the ability to make a rule, e.g., that a cost-benefit anal- policies in the past, like in the conflicts between eco-

ysis (CBA) supplemented by an environmental impact logical conservation and agricultural development in

assessment is needed to justify the decision. the Sanjiang Plain of China.56 Methods that account

In this section, we review different approaches for different types of knowledge and provide opportu-

(water social metabolism and ecosystem service assess- nities for participation and learning, support delibera-

ment) and methods, such as multicriteria evaluation tions in environmental conflicts.57 Such kind of social

(MCE) and conflict mapping, that political ecologists MCEs have been used, e.g., in cases of water conflict

can use in order to understand the implications of in Southern Europe.5860

water management for different types of groups, par-

ticularly those that usually lack recognition in stan-

dard evaluation procedures. The selected methods and Water Social Metabolism

approaches were chosen on different grounds directly From the point of view of social metabolism, the nat-

related with the key enquiries in political ecology. ural water cycle is a fund which constantly provides

First, they are tested methods that go beyondbut a flow of products and services, including water sup-

includemonetary costs and benefits. Second, they ply, an ever-renewable resource whose future avail-

are capable to recognize the values of water use and ability does not depend on whether we use more

unveil different ways to express them. Third, they can or less of it. Water evaporates using solar energy

be easily employed in bringing forward the voice of and precipitates in similar amounts from year-to-year

the less powerful (such as marginal groups and nature) although with regional variability. However, they are

when water gets (re-)distributed. also exhaustible water stocks. When groundwater

pumping exceeds the replenishment rate then the

aquifer gets depleted. This is similar to a biological

CBA Versus Plurality of Values and MCEs renewable resource (timber or fish) that can become

In economics, CBA has been applied since the 1940s exhausted, although here the renewal rate does not

to legitimize decisions on multipurpose development depend on the biological reproduction but on the

of river basins. It has traditionally played a key role infiltration of water. Another effect of the destruc-

in favoring dam projects,51 although it has also jus- tion of water stocks is salinization and the subsidence

tified dam decommissioning.52 CBAs since Krutillas and consequent compaction of the aquifer with loss

contribution53 considered recreational values (ameni- of storage capacity. Surface water stocks, as those

ties) of aquatic ecosystems for fishing or for sports in glaciers providing peasant communities with irri-

or for the contemplation of beautiful landscapes, as gation water,61 decline due to global climate change

monetary values growing in importance in time com- or direct impacts of human activities.61,62 What was

pared to the revenue from the production of electricity renewable becomes exhaustible.

and water for irrigation. Whatever its outcome, CBA Virtual water (VW) is the amount of water used

by definition imposes commensuration,54 with dis- in the process of production of goods throughout their

counted monetary valuationin actual or fictitious life cycle.63,64 The per capita consumption of VW

marketsof all cost and benefits. Commensuration contained in the diet varies according to the type of

precludes some groups from deploying valuation diet. While a subsistence diet may require volumes in

Volume 2, September/October 2015 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 539

Advanced Review wires.wiley.com/water

the order of 1 m3 /day, a meat-based diet means a use of Groot7375 supported vigorously the notion of envi-

VW of over 5 m3 /day.65 The volume of VW trade and ronmental services seeking to analyze how the ecolog-

the trade connections are twice as big as two decades ical functions serve human purposes, such as the water

ago, increasingly pressuring water scarce sources.66 cycle (evaporation and precipitation) and the carbon

In the same vein, the water footprint (WF) of cycle (Table 1). More recently, the initiative The Eco-

an entity (individual, community, or company) is the nomics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB)89 ded-

total volume of freshwater used to produce the goods icated one of its reports to the nexus between the

or services consumed by this entity.67 The concept hydrological cycle and the provision of ecosystem

can be divided into the blue water (that is extracted services in aquatic ecosystems such as coral reefs,

from the rivers, lakes, and aquifers in production coastal systems, mangroves, other wetlands, rivers,

processes, such as, e.g., irrigation), the green water and lakes.90

(evapotranspired during the growth of crops), and Environmental conflicts about water can be seen

grey water (contaminated by agricultural, industrial, as conflict over who takes advantage and who loses

or domestic use).68 The Water Footprint Networkb access to environmental services,91 either services of

provides examples pointing to the inequities in the use provision, regulation, cultural, or support. Table 1

of water. Chinas WF is in the order of 700 m3 /year provides supporting examples of water-related ecolog-

per capita, of which only 7% is obtained outside its ical distribution conflicts across these categories.

borders. In contrast, also in Asia, the Japanese have The complete appropriation of biophysical pro-

on average a footprint of 1150 m3 /year, 65% obtained cesses of river basins is often the foundation of

abroad. large projects of economic development, as in the

The potential for using VW and WF indica- long-standing efforts by the different countries along

tors for understanding tensions and power struggles the Mekong basin to build dams.79 However, tradeoffs

from water-related policy choices was noticed early between ecosystem services are common, as in the case

(e.g., interpreting the discourse for water in South- of irrigation and nature conservation19,56,86 or hydro-

ern Africa69 ) but not fully developed. In fact, while electric power production and support services.84,88

the VW and WF indicators account for the water From there, there is an emergence of social conflicts

flows associated with a given economic or social entity, that can be studied looking at the languages of valua-

they do not properly analyze the interdependencies tion deployed and the power of those involved.

between production and consumption processes and Ecosystem services are fundamental in the sur-

the properties of the water cycle in which they are vival and livelihoods of the rural poor and their loss

constrained.70 New developments in this respect high- may result in increased poverty.92 Today, it is common

light the limits of human appropriation of water, by to preach in favor of the payment for environmental

withdrawal or pollution, based on the stability of the services (PES) to deal with these conflicts. A city down-

ecological (hydrological) funds.71 stream can pay to communities upstream for taking

care of the water, compensating them financially for

The Ecosystem Service Approach conservation practices or for not contaminating with

Water has functions of ecosystem support prior to agrochemicals. Here the distribution of power and

any human extraction, because without them life the distribution of income are relevant, beyond mar-

would not be possible.2 Ecosystems water demands ket mechanisms and charming Coasian negotiations.

depend heavily on their plant communities. Thus, the For example, the sugar cane producers of the Valley

existence of areas with little natural vegetation can be of Cauca in Colombia make a token payment to the

understood as an ecological response to low rainfall. indigenous villages upstream.93 These payments are

The introduction of irrigated vegetation in such areas gradually changing property rights, so that the pow-

generates scarcity, as with the introduction of golf erful cane growers feel already as owners of the water

courses covered by grass in the Mediterranean, or against the indigenous populations. The use of the

the extension of the agriculture frontier in seasonally ecosystem services framework, in particularly in rela-

water-scarce areas.19 In absence of this, the natural tion with PES, is seen as a step forward in the direc-

availability of water in each territory determines the tion of natures commoditization.94 For this reason,

kind of benefits that humans can expect of their its application for the study of environmental con-

ecosystems. flicts is fiercely contested by some EJ organizations.

The identification of the environmental services Moreover, to offset damage is not always possible.

provided by aquatic ecosystems is important for polit- A confluence of rivers (prayag, in the Himalayas) or

ical ecology. In the 1990s, one decade before the 2005 a waterfall can be a place of worship, sacred to the

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Daily72 and De local population.83 If it is destroyed to build a dam,

540 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Volume 2, September/October 2015

WIREs Water Political ecology of water conicts

TABLE 1 Ecological Distribution Conicts on Water and Ecosystem Service Provision

Categories Services Example of related References

Provision Food provision (biophysical base for Tensions in transition from commercial shing to an 76

shing, hunting, and grazing) amenity economy in coastal areas of North Carolina

Provision of raw materials (bers and Tree plantation conicts (Ecuador, Cameroon, and South 77 and 78

wood) Africa) with water-related claims

Domestic water supply Arsenic contamination of drinking water in Bangladesh 9

Agricultural water supply Increase demands for irrigation: after the Green 19 and 56

Revolution in Thailand; since 1950s in large-scale

farming in China

Hydropower production Large-scale hydroelectric development in the Mekong 79

river leads to inland sheries decline

Regulation Water purication In Colombia, wetland ecosystems 80

(pramos)threatened by coal and gold

miningpurify water at a rate of 28 m3 /s

Flood regulation Opposition to deliberate breaching of levees in 81

agricultural areas increased the intensity of ood

wave in the River Odra, Poland, 1997

Biological control Worlds largest macroalgal blooms during 20082012 82

associated with aquaculture in the Yellow Sea, China

Cultural Tourism, recreation, and aesthetics Water inequity in Bali associated with tourism activities 30

Customary rights Customary access to water impaired by tree plantations 57

in Cameroon

Spiritual and religious benets Sacred rivers in South Asia (e.g., Ganges-Brahmaputra), 83

degraded by pollution and dam building

Support Contribution to the primary production Decrease in nutrient loadings in the Yangtze River 84 and 85

Estuary and the East China Sea after impoundment of

the Three Gorges Dam with over 80% decline in

primary production

Wildlife habitat Wetland conservation threatened by agricultural 56 and 86

development in Qixinghe, China; and by irrigation

infrastructures in the Rio Grande/Bravo

Sediment and nutrient retention and Globally, articial impoundments possibly trap more 87 and 88

mobilization than half of basin-scale sediment ux in regulated

basins

monetary compensation cannot really offset the values embraces the political nature of mapping practices95

destroyed. using critically the discipline of cartography as an

instrument of liberation rather than a tool of power

control.96,97

Water Conflict Mapping A global EJ research initiative, the project

Here we connect specific cases to the logic of a Environmental Justice Organisations, Liabilities and

widespread water justice movement which is itself Trade (EJOLT),g is currently compiling a database

part of a global EJ movement. For decades, networks of ecological distribution conflicts on different topics,

involved in water conflicts caused by oil companies including water. The classification system of conflicts

(such as Oilwatchc ), dams (as International Riversd or in this project is based on the idea that the increase

MABe in Brazil), or mining (such as the Latin Ameri- of social metabolism in terms of use of energy and

can Observatory OCMALf ) have supported advocacy materials (including water) leads to the growth of

and information sharing. The analysis of conflicts environmental conflicts.

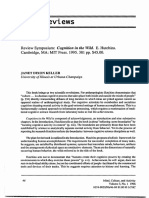

beyond the observation of single case studies has As an example of mapping, Figure 1 shows

been greatly facilitated through the creation of ad hoc emblematic water conflicts in Catalonia.98 The small

databases linked to these networks of activism. This number of cases does not allow statistical analysis

Volume 2, September/October 2015 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 541

Advanced Review wires.wiley.com/water

0 1 3

France

Andorra

Environm. flows

of the Segre

Groundwater nitrate pollution Ter

42 in Osona (pig farming)

42

gre Girona

Se Environm. flows

Salt mining

of the Ter

in Sallent

Urbanization

of the Anoia

Lleida River banks

Llo

Segarra-Garrigues

bre

An

Canal

ga

oia

The insatiable thirst

t

i

of Barcelona

Ga

Privatization of ATLL

Industrial toxic sediments Barcelona

(public water operator)

in the Flix Reservoir Environm. flows

of the Gai Paving of

the Llobregat Delta

Tarragona

Mediterranean Sea

The Ebro

transfer

Ebro

Water conflicts:

Pollution

40 Supply

To the Xuquer and Segura

40

receiving basins Urban pressure

Environmental flows

0 50 km

0 1 3

FIGURE 1 | Water conicts in Catalonia, Source: Own elaboration with cartographic data of the Ministry of Planning and Sustainability of the

Generalitat de Catalunya, the Cartographic and Geological Institute of Catalonia (ICC), and GADM online repository. Cases from Ref 98. Note:

Pollution conicts [Groundwater nitrate pollution in Osona (pig farming); Industrial toxic sediments in the Flix Reservoir; Potash mining in Sallent];

Supply conicts (Ebro water transfer; Segarra-Garrigues Canal; the insatiable thirst of Barcelona: the Ter, the Ebro, the Rhone); Conicts from urban

pressure (Urbanization of the Anoia River banks; Paving of the Llobregat Delta; Privatization of ATLL, public water operator); Conicts for

environmental ows (in the Ter, Segre, and Gai rivers).

here, but points to a classification of four kinds of Aiges Ter Llobregat. Finally, the debates on environ-

conflicts. There are cases of pollution of agricultural mental flows, crucial in the management of Mediter-

origin (pig manure in the Osona region), of indus- ranean rivers, are represented by the cases of the Ter

trial origin (persistent organic pollutants and mercury and the Segre rivers, and the extreme case of the Gai

in the Flix reservoir), and conflicts caused by mate- River legally deprived of water by the petrochemical

rial extraction (Sallent potash mines). Supply conflicts industry until the year 2050.

are represented by the emblematic Ebro water transfer,

and also by the construction of the Segarra-Garrigues ECOLOGICAL DISTRIBUTION AND

canal for irrigation, as well as the demands imposed

by the metropolitan area of Barcelona. Other conflicts

WATER JUSTICE CONFLICTS

are related to geomorphological alteration (as on the Classifying water conflicts helps to understand their

banks of the Anoia River or the Llobregat delta) or causes and to analyze issuessuch as scale99 and

to privatization of the public distribution company power distribution100 that disclose possibilities for

542 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Volume 2, September/October 2015

WIREs Water Political ecology of water conicts

intervention promoting water justice. A starting point More than 45,000 dams over 15 m high alter

to address water conflicts under a political ecology ecosystems and damage the populations that depended

perspective is to consider them as a particular form on them, in all major river systems of the planet.107

of ecological distribution conflicts, which are social Upstream, dams displace population without ade-

disputes on the use of natural resources or the burden quate compensation or relocation. Archaeological

of pollution.26,101 From there, it could be asked what remains, cropland and biodiversity are lost. Down-

types of water conflicts exist and how they can be stream, water becomes scarce, fishing disappears. It

classified. An analysis based on frequencies would be is reported that 472 million people have been neg-

advisable, although it is still challenging. Ongoing atively affected downstream of large dams.108 There

efforts to systematize knowledge about ecological is also the risk of dam failure. In exchange, electric-

distribution conflicts, such as the EJOLT Atlas, or ity is produced and there is water for irrigation or

geopolitical conflicts that are also water conflicts, such for urban use. Who wins and who loses, now and in

as the Water Conflict Chronology,102 show hundreds the future? Regulated river systems alter the ecologi-

of conflicts that are probably increasing in number cal diversity and the ecosystem functions, temperature

over time. and sediment flows. Reservoirs go hand-in-hand with

In order to contribute to formalize a typology, biotic homogenization by the deliberate or accidental

we take then an approach based on the political introduction of alien species favored by environmental

salience of the conflicts from early protests against conditions in reservoirs.109

dams in the mid-20th century to more recent and Today, the most controversial dam across Latin

politically crucial conflicts on urban and rural water America is Belo Monte, which is being built despite

management, and to conflicts caused by the use of indigenous and environmental protests on the Xingu

water in extractive industries. Based on this empirical River in Par near Altamira. Its capacity of perhaps

background, a general classification of water conflicts 11,000 MW will make it the worlds third largest after

is offered and discussed at the end of the section. the Three Gorges in China (20,300 MW) and Itaip

on the border ParaguayBrazil (14,000 MW).110 It is

Conflicts over Large Infrastructures (Dams, often argued that hydroelectric dams produce electric-

Water Transfers, and Waterways) ity without producing CO2 , as they do not burn char-

As analyzed above, water has important ecological coal, coal, or gas. Sometimes they are given carbon

functions that the market forgets. Ecological func- credits. However, Belo Monte means the destruction

tions become environmental services providing mone- of a very large area of forest storing and absorbing

tary and nonmonetary values to humans.90,103 In the CO2 . In addition, forests flooded will rot under water

mid-20th century, large dams became fashionable, dis- and will generate methane which is another green-

rupting river courses. It did not matter whether politi- house gas.111

cal regimes were democratic or not, whether rigorous In India, the dams in the Himalayas and the

CBAs were deployed or not. Under Nehru or under Northeast involve 50,000 MW of power.83 Estimates

Mao, under Franco or Nasser or in the United States, on the distributional effects of dam construction in

in the former USSR, Brazil, or China, progress meant India suggests upstream to downstream transfer of

and still means large dams. wealth that, in aggregate, has increased poverty.112

There have been dissenting voices against dams Despite this evidence, there are plans for new large

for a long time. In 2000, the World Commission of dams in other parts of the world, such as Grand

Dams (WCD) published a report that brought an Inga dam in the Republic of the Congo.113 Not only

innovative approach, criticizing Cost Benefit Analysis, large dams but also the concentration of small dams

seeking to protect the natural environment and those generates discontent among different types of social

affected by dams.104 Medha Patkar, a leading voice actors.91

of the Narmada Bachao Andolan in India, was a There are many technical and institutional inter-

member of the commission. Author Patrick McCully dependencies between the construction of contested

and the International Rivers Network had provided water-management infrastructures and other projects

full information and critical views on the construction such as mines, plantations, or utilities that in turn

of large dams.105 Confronted with the fact that the cause social conflict. The historical and anthropo-

Ganges and its tributaries are now being dammed,83 logical perspectives emphasize the role of physical

the director of the Centre for Science and Environment infrastructures and the institutions that sustain

in Delhi, Sunita Narain, recently asked for a minimum them as intrinsic factors of political and economic

environmental flow of 50% in all projects in the winter developments.86,114 In this respect, the type of infras-

season before the monsoon.106 tructures mentioned here tend to lock in concentrated

Volume 2, September/October 2015 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 543

Advanced Review wires.wiley.com/water

power and wealth for the benefit of actors outside the water services. Failed cases of privatization, like

territories where the infrastructures are located. Cochabamba121 and Buenos Aires,122 have led to a

Dams are the main modernizing factor in the new trend of restoring public water management,

control of rivers, but not the only one. Other con- as described below. The privatization debate is not

troversial interventions in the hydrosocial cycle are restricted to urban water uses, but equally important

water transfers between river basinssuch as the in rural water use (related to privatizing agricultural

transposio of the So Francisco River in Brazil, water rights and the transfer of irrigation systems from

approved in 2005, that even led to a bishops huger government to private entities).123,124

strike115 and also some waterwayssuch as the Critics of privatization argue that private partic-

ParaguayParan hidrova among Argentina, Bolivia, ipation in water management, and the resultant com-

Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay within the IIRSA mercialization of water, only help to increase profits of

frameworkh .116 a few large transnational corporations.125 The multi-

national nature of many of the companies involved

Imposition of Centralized Water is one of the critiques but not the only one. Another

major concern is that neoliberal policies treat water as

Management and the Privatization a commodity. Therefore, its management aims at gen-

Controversy erating profits rather than providing a good service

Similar controversies surround the development of to which both rich and poor are entitled.126 More-

large infrastructures for urban water supply handing over, larger profits are gained by selling cubic meters of

over water management to the private sector at the water than by taking care of the natural environment.

expense of community-based alternatives, as in the Notice, however, that the increasing use of

case of the Melamchi Water Supply megaproject in waterfor domestic use but also for irrigation and

Nepal.117 In South Africa, there are constant com- industriesis not just a product of the search for prof-

plaints against high charges for water (and electricity) its. It is due to the growth of the social metabolism that

to poor households that are disconnected if they do demands more energy, more materials and generates

not pay, while export mining companies enjoy subsi- more waste. This growth requires interventions in the

dized rates.118 hydrosocial cycle and changes in the water landscapes.

A decade ago, the privatization trend was partic- Increased efficiencies in water use (e.g., through mod-

ularly manifest in the United States and the UK,119 but ernization in irrigation infrastructures) may lead to a

expanded globally afterward. Decades of policies of Jevons effect,71 meaning that water use increases more

neoliberal inspiration inextricably associate efficiency than proportionally to the water savings, nullifying

with the participation of the private sector in water the efficiency improvement. This increase in water use

management, despite meager or adverse empirical evi- would surely happen as well under state capitalism or

dence in this respect.107109 under postneoliberal governments.

Reviewing the Latin American scenario, Chile

appears as an exemplary case. As in other sectors of

national economic life, private economic groups con-

Water Conflicts Related to Material

trol water, protected by a Water Code consistent with Extraction (Biomass, Mining, and Fossil

the 1980 Constitution. According to this, 90% of the Fuels)

rights of access to water are concentrated in large com- Many conflicts over the use of biomass, mining, and

panies, often linked to mining interests, in a context other extractive activities, are indirectly conflicts over

of poor regulation of minimum environmental flows. water. Such connections have been shown by social

Since 2008 to date, several initiatives to restore the movements in India with the slogan Jal-Jungle-Zamin

status of water as a state property have not yielded (water, forest, and land). When a geographical area

a constitutional reform. Equitable access to water exports biomass to another area, there is also an

and environmental conditions have been negatively export of the water used to grow that biomass, as it

impacted by water withdrawal toward private pro- happens in the cases of Colombian and Argentinean

duction of electricity or mining, as elaborated below. exports of coffee, flowers and soybeans.127,128 Some-

Here, the dimensions of water injustice include lack of times, trade creates fatal links. For instance, nearly one

priority for the most needed applications, such as local quarter of the exports of Uzbekistan and Pakistan, are

agriculture, the award of free and perpetual rights of raw cotton and yarns produced using locally scarce

use to private operators, and the lack of recognition water.66 Water accounts, including VW exports, are

to indigenous peoples rights.120 therefore relevant for claims of ecologically unequal

In the past 20 years, there have been many trade. The water used to grow commercial planta-

other conflicts against the privatization of urban tions is not available for biodiversity conservation or

544 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Volume 2, September/October 2015

WIREs Water Political ecology of water conicts

the provision of valuable ecosystem services.78 Every cannot afford to buy bottled water. Therefore, when

year, global water grabbing appropriates tens of thou- the rural poor see their own subsistence threatened

sands of cubic hectometers of rainwater and irriga- by a mining project, a dam or a tree plantation or a

tion water for crop and livestock production.129 In large industrial area, they often protest not because

some cases, the per capita volumes grabbed exceed the they are card-carrying environmentalists but because

requirements to abate malnourishment in the grabbed they immediately need the services of nature for

countries.129 their own survival. That is the environmentalism of

Eucalyptus plantations generate water conflicts the poor and indigenous,137 present everywhere in

worldwide.130 Since the 1970s, huge areas of euca- movements of resistance at the frontiers of extraction

lyptus plantation have been rightly tagged as green and pollution.77,134

deserts.131 The concept refers to the loss of biodiver- Indigenous peoples, whose holistic rationalities

sity in monocultures but also to water depletion gen- collide against the utilitarian views of the mining

erated by alien-tree plantations around the world.77,78 industry,134 often lead the protests. In Panama, the

Conflicts on energy crops include controversies about Petaquilla Gold project in Donoso meant the illegal

sugarcane and jatropha plantations, among others. removal of forest cover, the destruction of river beds

Governmental authorities assert in India and else- and the throwing of mining waste to rivers. The

where that Jatropha curcas for biodiesel grows with ethnic group Rey Quibin demonstrated in defense

little water and is drought-tolerant. However, if there of water outside the headquarters of the company

is not enough rainfall or irrigation, the plant might in Canada.138 The Ngbe-Bugl cacica, Silvia Carrera,

survive but its performance is much reduced. In prac- led opposition to a new mining law in 2012. The

tice, jatropha competes for water and land with other Ngbe-Bugl sing an anthem in their ceremonies

crops, as shown in detail in villages of Tamil Nadu.132 expressing reverence toward the water and rivers.139

Mining also drags disputes over (surface- and Another mining-related item in the political ecol-

ground-) water depletion and pollution, both in nat- ogy of water is the bursting of tailings dams (pre-

urally scarce and in water rich areas.133 For instance, sas de jales, diques de relaves). A case in point hap-

in South Africa and in Chile the mining and energy pened in Andalusia in 1998, where polluting waste

complex exacerbates pressures on access to water was released by a tailings dam failure from a mine

sources.118 Thus, Chiles antimining protests are also owned by the Swedish-Canadian company Boliden,

about dams in the South for electricity or about deple- located in Aznalcollar. The waste flew to the Gua-

tion of scarce water sources and their contamination diamar River bordering the Doana National Park.

in the North.134 Barrick Gold had to stop its operation Restoration costs reached 90 million, paid for by the

in Pascua Lama because it was destroying glaciers.62 regional government, the Junta de Andaluca.140

In Peru, the most water-stressed country of Less notorious than copper, gold, bauxite, iron

South America, over 50% of peasant communities ore, or uranium mining, the extraction of gravel and

have been affected by mining activities.135 In Caja- sand as building materials is an important item in the

marca, the Newmont Mining Corporation (USA) calculations of the material flows of any economy. In

and the Buenaventura Company (Peru) are the main India, there are many conflicts on sand and gravel min-

shareholders of Minera Yanacocha which operates ing in rivers, with complaints against sand mafias.133

one of the world largest gold mines. The environ- In Latin America, the conspicuous conflict in the Tun-

mental liabilities involve destroyed hills, and illegally juelo River in Bogota is between the sand and gravel

appropriated water polluted in several provinces. companies Holcim, Cemex, together with the Arch-

Activist leader Marco Arana helped save Cerro Quil- diocese of Bogot, and the local population fearing by

ish, a water reserve for the city of Cajamarca. In 2012, experience that changing the morphology of the river

there was again resistance against a new gold mine leads to floods and mudslides.

named Conga that would destroy some lakes. Its final Also noteworthy, conflicts due to impacts of fos-

outcome is undecided. The demonstrators motto was sil fuels on water quality are particularly intense in the

el agua vale ms que el oro [water is worth more than extraction and transport stages. In one famous case

gold].136 in Ecuador, between 1965 and 1990 Chevron-Texaco

Take the case of a mining company, such as deposited the extraction water coming out with oil in

Vedanta, Tata, and Birla, contaminating the water in pools of heavily polluted water harming soils and

a village of India by the mining of bauxite, iron ores, groundwater. The company is liable for USD 9.5 bil-

or coal. Families have no choice but to use water lion for the extreme damage done to the waters, soils,

from streams or wells. If the water of a stream or the and the health of the people. The implications of the

local aquifer is contaminated by mining, poor women historical court decision of 14 February 2011 (ratified

Volume 2, September/October 2015 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 545

Advanced Review wires.wiley.com/water

TABLE 2 Classication of Socioenvironmental Conicts over Water/Aquatic Ecosystems

Stage of the Commodity Scale

Chain Local National and Regional Global

19 56

Extraction Dams Large scale irrigation developments Global water grabbing129

Desalination24 Water for industrial tree plantations77 or Trend toward the

Water for mineral extraction134,135 for agrofuel crops132 privatization of water

Sand mining in river beds133 Unsustainable sheries76 supply (and sanitation)122

Water used in oil142 or gas145 Negative impacts of aquaculture 82

extraction Tourisms water demands30

Transport and trade Water supply megaprojects (urban117 Transfers between basins19 Trade of virtual water151

and agricultural86 ) Stairways of dams79

Effects of transport infrastructure in Waterways (hidrovas)116

aquifers and rivers150

Oil spills at sea147,148

Waste and pollution, Urban pollution load into rivers81 Acid rain152 Ocean acidication154

postconsumption Groundwater contamination from Pollution of entire watersheds153 Glacier retreat due to

diverse nitrate sources (e.g. climate change61

intensive farming and synthetic

fertilizers)10

on appeal in 2012 and 2013) have been extensively or it can be the element impacted by a contested

analyzed as a case of environmental injustice.141,142 project. Commodities move from extraction, through

Similar cases of damage by state or private companies, transport to consumption and waste. Table 2 catalogs

such as Shell in the Niger Delta over many decades, conflicts along this chain, through which water is used

have been also documented.143 More recently, the con- (e.g., by extracting it trough a dam, desalinating it,

troversy on the impact of tar sands144 and shale gas transporting it through a water supply infrastructure

fracking145,146 on aquifers has fuelled the discussion or dumping it to a river after being used in urban

on environmental conflicts. In the transport stage, oil areas). Besides such conflicts, there are cases where

spills in the sea, such as the cases of the Exxon Valdez water is used in order to enable other commoditization

in the United States or the Prestige in Spain, have con- processes (e.g., mineral and fossil fuel extraction and

tributed to create awareness at national and interna- transportation; agriculture, aquaculture and agrofuel

tional scales.147,148 production, or recreational services). Along these

processes, the quantity and quality of water are

modified to the benefit of some actors but becomes

An Elaboration of the Concept of Water inaccessible for other users and this generates conflict.

Conflict From a metabolic perspective, many water uses

To make sense of the cases presented above and of are unjust and ecologically harmful, affecting in par-

the hundreds of water conflicts that could be added ticular local communities who depend on the water

to the account, in this section we present a typology sources for their livelihoods and survival, and who

of water conflicts, applying classification principles often do not benefit from the (economic) profits

of ecological distribution conflicts.149 Accordingly, that new water-related commodities yield. Specific

Table 2 classifies water conflicts in two axes: first, by water interventions entail redistributions across social

the stage in the commodity chain (as defined by Raikes groupsnot just of water, but also of the costs

et al.155 ) when the conflict occurs (the extraction, and benefits of accessing it and of water-derived

transport, or postconsumption pollution); and second, incomesbenefiting particular groups rather than

by their geographical scale. The cases and examples others and with detrimental impacts on the environ-

presented fit into this classification, which is also ment.

enriched with a systematic review from the literature. Water conflict is sometimes understood as polit-

As already argued, water conflicts arise because ical disputes between countries or states.102 Our

of growth of the social metabolism. From a metabolic classification offers an entry point to this type of

point of view, water can be the commodity in geopolitical interpretation, which is not the main

dispute, as in the case of water privatization conflicts, focus of analysis here. Moreover, against geopolitical

546 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Volume 2, September/October 2015

WIREs Water Political ecology of water conicts

pessimists who announce water wars more intense Karl Wittfogel established the correspondence

than wars for oil,156 one can show a certain techno- among lack of water, large irrigation works, and

logical optimism, for instance regarding desalination oriental despotism, establishing a link between

for urban water needs.20 This is different from push- water management and state power.160,161 However,

ing desalination for mining (as in Northern Chile), for already in areas of ancient irrigated agriculture, there

agricultural luxury exports (as in coastal Peru), or for have been community institutions of water users.

rich tourists in the Canary Islands.24 In the Andes, the offerings to the Apus (big snowy

The processes under analysis happen at differ- mountains)which are the water source for terraced

ent geographic scales. Table 2 shows local conflicts valleysgo together with community-regulated work

(e.g., the use of lake water in mining like in the pro- on the channels for irrigation.4 In southern India, Sri

posed Conga gold mine in Peru) and global conflicts Lanka and Bali the local temples have regulated the

(e.g., human-induced global change leads to glacier water uses. Each temple had its tank of water (a small

retreat and possibly to ocean acidification related to earth dam) for community water fulfilling also other

carbon dioxide emissions and therefore to climate ecosystem services.162,163 Of course, community regu-

injustices). Leaving aside these examples related with lation of water use certainly does not imply equitable

global change, water-related conflicts usually have a regulation as regards gender and caste.

geographically more restricted reach. For example, the In many villages in India, communities have

diversion of the So Francisco River is a regional sub- built new physical structures of water harvesting.

ject, affecting several Brazilian states. Also interlink- Social institutions arise which allow cooperation and

ing of the rivers projects in India, Thailand19 or more regulate water use by banning for example commercial

modestly the Tajo-Segura or the Ebro water transfers crops requiring too much water. As described in the

in Spain generate regional or national debates. They case of Hiware Bazar, a new community institutions

exceed the local level but they are not global issues. of water audit was introduced at village level.164

However, several examples mentioned in this When water has been scarce, society itself has created

article are simultaneously local and global: a violent institutions to manage it.165 Nevertheless, in a context

mining conflict may be local, but it is driven by a of strong social hierarchies, a rule of groundwater

globalized commodity and VW export chain. Simi- capture has often persisted to the benefit of the

larly, large-scale irrigation conflicts are presented in powerful. Then, if the effort to draw water is reduced

Table 2 as national/regional issues butwhile linked by new technological means, excessive groundwater

to global agroindustrial processesmay be simul- withdrawals are likely.166 A new rule should have been

taneously local and global. This type of local or instituted.

national conflicts becomes thus glocal62 when they Three options of water managementcom-

occur locally in several places, responding to global munity, state-run, or privatized managementare

drivers, or when acquiring global importance. As men- valid to avoid problems of open access. However, the

tioned above, that was the case of the dams in the social implications of each one are different. Com-

Narmada River in India that helped constitute the munity institutions can easily articulate ecological,

World Commission on Dams.104 Here, the concept of livelihood, and cultural values (such as sacredness).

jumping scales is pertinent.157 In this vein, the study Still, nowadays they are not given much chance to

now focuses on the potential from creative resistance flourish in the midst of an ideological clash between

and new water governance institutions born from con- state administration and private management of

flicts. water.

HERE IS THE POLITICAL: NEW

INSTITUTIONS FOR WATER National and Transnational Networks

MANAGEMENT BORN FROM of Water Justice

Water conflicts can become a real boost to institutional

CONFLICTS innovations. This is true at levels of local community

Reconciling competing values in water-related debates management, and also for public policies. Thus, in

is not exempt of difficulties, particularly when formal Spain, the reaction against the diversion of the Ebro

political institutions are resistant to change.76 How- foreseen in the National Hydrological Plan (NHP) of

ever, as shown in this section, social movements born 2001167 triggered massive local protests opening also a

from water conflicts are effective providers of alterna- broad debate involving social movements and the sci-

tives that reshape power configurations,158 against the entific community. Many social groups popularized a

view that EJ movements are postpolitical.159 so-called New Water Culture, such as the Platform for

Volume 2, September/October 2015 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 547

Advanced Review wires.wiley.com/water

the Defense of the Ebro River,i whose symbol (a knot- (binational with Paraguay), Sobradinho (Bahia), Ita-

ted pipe) became an icon, and the New Water Culture parica (Pernambuco, Bahia), and other smaller dams

Foundation,j a forum of academics and professionals in Rio Grande do Sul.

active in water management policies. In Mexico, there are famous conflicts on La

The NHP of 2001 was defeated.168 This achieve- Parota dam or El Zapotillo dam. In Las Cruces,

ment was twofold. On the one hand, the New San Pedro River in Nayarit, the upstream indigenous

Water Culture (relying on water demand manage- Cora people are in alliance with downstream fish-

ment, and the ecosystem approach) became a dom- ers and shell collectors. The Mexican Movement of

inant discourse at the political level. Such principles People Affected by Dams and in Defense of Rivers

are fully consistent with the Water Framework Direc- (MAPDER),k founded in 2004, brings together social

tive (2000/60/EC)169 that guides the European Unions organizations and communities impacted by the con-

water policy. Opponents to the Ebro water trans- struction of dams, dealing comprehensively with the

fer counted on support from Brussels. On the other defense of rivers, land, and human rights.

hand, the intensity of the movement against the NHP In Colombia, CENSAT Agua Vival is a member

contributed to strengthen representation and political of Friends of the Earth international. It has different

clout of other movements in the Ebro region against areas of work, including mining. CENSAT is one of

thermoelectric power plants, wind energy farms, and the major Latin American organizations for water

for the defense of the natural environment. As an justice fighting against dams, and addressing water

activist said: When they are born, these social move- privatization and its inclusion in free trade agreements

ments make evident the divorce between state policies and other international agreements.

and the local territory, they are policies of remoteness The above-mentioned national networks play an

and oblivion [ ]; our mobilizations respond to a feel- important role in linking actors and local organiza-

ing of defending the territory and a different model tions in different places. They coordinate international

to that they want to impose on us (Roser Vernet, in efforts with other related movements concerned with

La Vanguardia, September 7, 2005). This is a view the similar issues and transversally with organizations

of territorial claims that fits into EJ and water jus- working on related types of environmental conflicts.

tice, distant from the NIMBY claims alleged by the An interesting feature of national networks is their

authorities. ability to synthesize local experiences in broader dis-

Water is a then a key ground in the reconfig- cussions, through their participation or dialog with

uration of spaces of ecopolitical engagement, where international bodies and increasing awareness among

citizenship (and sometimes, ethnicity) plays a central citizens of countries where corporations come from.

role.170 In Latin America, there are numerous civil At the continental level, one entity support-

society organizations dealing with topics related to ing water justice is the Latin American Water Tri-

water. It is common that bottomup movements or bunal (TLA)m bringing ethical resolutions with a

networks against mining (like RECLAME in Colom- base on current legislation to controversies related to

bia or No a la mina in Argentina) or promoting resis- water systems. Meanwhile, a Latin American network

tance to monoculture tree plantations (such as the against dams and for rivers and water (REDLAR),n

World Rainforest Movement) include water among established in 1999, brings together many organiza-

their main demands. Listed below and very briefly tions from 18 countries in the region. At a larger scale,

described, are three important national networks since 1985 an international network of people affected

whose line of action is linked specifically to water con- by dams and of grassroots organizations with repre-

flicts. sentation in five continents has drawn support from

The Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens the International Rivers Network.d

(MAB) is a Brazilian movement of collective action

in the fight against dams, with origins in the 1970s.

The military government supported the development Remunicipalization of Water Management

of hydropower that meant the displacement of tens of Services

thousands of people. While political forces such as the Following the neoliberal wave of the 1980s and 1990s,

Movement of Landless Workers or the Workers Party there were municipal milestones of the struggle for

were growing, the discontent on dams was channelled water justice, as the emblematic opposition to priva-

through regional commissions of affected (atingido) tization of the urban water supply in Cochabamba

people resisting hydroelectric projects or, at least, (Bolivia).121 In 1999, a private concession of the

demanding fair compensation and acquisition of new municipal water distribution company was granted,

lands. Emblematic cases were Tucuru (Par), Itaipu linked to a water transfer called Misicuni project. At

548 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Volume 2, September/October 2015

WIREs Water Political ecology of water conicts

the same time, at the national level, regulation of the conflicts, as in the case of reduced infiltration by lining

water supply and sanitation was influenced by World earthen canals, which is detrimental for the preserva-

Bank recommendations and the so-called Washing- tion of groundwater or wetlands.

ton Consensus. The protest movement organized a In rich economies with well fed citizens, it

Departmental Coordinating Platform for Water and appears reasonable to aim at savings in agricultural

Life, which grew until a symbolic occupation of the water use, to transfer it to more profitable or prior-

city of Cochabamba was brutally repressed. Then in ity uses or simply to increase river flows. Economic

April 2000, the Coordinadora submitted the priva- instruments such as higher prices (which should reflect

tizing measures to a popular referendum. The result the costs of the infrastructures built by public admin-

was 90% favorable to public management. Facing istrations) can stimulate the efficiency in water use.

such massive and permanent mobilization, the govern- Markets for water may be introduced, whose opera-

ment finally rescinded the privatization contract giving tion depends on given allocations of property rights.

the water management to the Coordinadora, together The commercial transfers of rights of use of water are

with the considerable debt of the company. Since then, not always wrong, as part of a policy of demand man-

water management in Cochabamba emerged as an agement against the traditional policy of increasing

example of struggle against the advance of the water supply by building dams and water transfers.

multinationals. However, there remain supply prob- A water market works as follows. If a Federation

lems in some areas of the city, mitigated through the of Irrigators or a private person wants to sell the

creation of local water committees. water for urban supply, this may be allowed (especially

The tendency to regain public control of water if the buyer is not far away), taking into account

management is forceful. Cases of remunipalization ecological factors and possible effects on third parties

have been documented for Paris (France), Dar es beyond the economic interests of buyers and sellers.

Salaam (Tanzania), Hamilton (Canada), Malaysia (at The best-known case is the California water banks

national level), and Buenos Aires (Argentina).171 active in the early 1990s in times of shortage because

The defense of the public management of water of a drought. A public entity bought water from

let to a constitutional reform in Uruguay in 2004.172 farmers at a fixed price, i.e., the commitment not to use

Meanwhile, some privatization initiatives continue this water, and sold it to a higher price to urban buyers

to be truncated. Thus, in 2012 the privatization or kept it for nonmarket environmental applications.

of El Canal de Isabel II, Madrid, proposed by the If the instrument is the market, we must bear in

regional government, did not take place because of mind that the economically efficient use is always in

popular opposition, in a consultation in which 99% relation to a particular structure of initial allocations

of 167,000 participants voted in favor of an entirely of water rights to different regions and social groups,

public management of the water operator. Moreover, and also to the purchasing power of users, which may

the economic crisis probably meant lack of interest be very uneven.

from potential investors.173 A demand approach does not mean that priori-

ties should be established by the market. For example,

Water Markets and Water Rights in Gujarat and Maharashtra profitable capitalist sugar

As explained above, the increased use of water in cane growing steals water from poor and low caste

the world is not due only to domestic or indus- families. In poor countries where the population

trial demand but also to irrigated agriculture. Con- depends for food on the irrigated land (India, Pak-

flicts of access for irrigation water have always istan, China, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, and in part Mexico

occurred, as in farmer-herder conflicts in Tanzania174 and Peru), the argument that water should go to more

or the Sahel,175 exacerbated by increased compe- profitable uses is not appropriate: chrematistic prior-

tition over resources. Expanding agricultural fron- ities are rarely social priorities.

tiers and agricultural modernization in Thailand19 or

China56 relying on increased water useaggravated

water conflict among users at different scales.

Rights Emerging from Conflicts? The

Water efficiency in agriculture is therefore a Human Right to Water and the Rights

key issue in response to water conflicts.56 Scarcity of Nature

and high water costs have led to new technologies There is a relationship between income and con-

such as drip or spray irrigation in the of the Mex- sumption of water that, for domestic purposes,

ico/US border.86 However, as mentioned above, these ranges between 1000 liters per person per day (pppd)

efficiency schemes appear to have caused a Jevons among the richest people in California and 30 liters

paradox. Moreover, these technologies can cause new pppd of the urban poorest. Under 20 liters, cholera

Volume 2, September/October 2015 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 549

Advanced Review wires.wiley.com/water

TABLE 3 Slogans of Water Activism

Slogan Campaign/Organization Country

We are water March for Life, with various organizations led by CONAIE, the Ecuador

Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuador

For water, for life No a la Mina Argentina

Rivers for life, our lives are the rivers Taller Ecologista, Rosario Argentina

Life cannot be stopped Without Sogamoso River Dam, Rios Vivos Colombia

Water, a fundamental right Committee on Social JusticeDiocese of Chimbote/National Peru

Coordinator of Human Rights

Water is a human right European Citizens Initiative Water and sanitation are a human European Union

right! Water is a public good, not a commodity!

Water is a right, not a commodity Engineering without borders International

Source: Own elaboration based on internet search.

might appear. When reaching 1000 liters pppd, or water are grounded in emotional geographies related

even before, the income elasticity of domestic water with everyday survival struggles.9 On the other hand,

demand drops to zero. the idea that access to water has to be approached

Domestic water use not only depends on the under the (human) rights rationale. Backing such

income level but also on cultural factors (including universalist demands, the World Health Organization

awareness of the need for water savings) and lifestyles and UNICEF recognize that almost 900 million people

(such as the type of housing and urban settlement), lack access to safe drinking water and 2.5 billion

and of course on the fee structure. In this respect, the (35% of the world population) do not have adequate

2003 World Water Forum in Kyoto was a major mile- sanitation.177

stone for the global water justice movement. There, In July 2010, after 15 years of debates, the UN

the proprivatization World Water Councils claimed a General Assembly adopted a resolution that recog-

consensus on a corporate-controlled future for water nized explicitly the human right to drinking water

that raised strong opposition. The firm commitment and sanitation.178,179 The representative of Bolivia in

of the Council of Canadians was a key contribution the General Assembly, Pablo Soln, emphasized that

to build an alliance with its own Vision Statement drinking water and sanitation are not only elements

under the slogan Water is Life. Since then, an Alter- or components of other rights such as the right to

native World Water Forum (FAME, from the French an adequate standard of living. The right to drink-

acronym) has taken place in parallel to the official ing water and sanitation are independent rights which

water forum and in the same cities (Mexico 2006, should be recognized as such. [ ] It is necessary to

Istanbul 2009, and Marseille 2012), bringing together call on States to promote and protect the human right

water justice organizations, advocacy groups, schol- to drinking water and sanitation.180

ars, journalists, local activists, and committees. It has Food and Water Watch, Red Vida at the

been a watchdog on policies pushed forward by the pan-American level, Focus on the Global South,

World Bank, corporations, and governments, includ- Jubilee South, the African Water Movement are

ing the European Union.158 There is now a water working toward actions and tools for the concrete

movement at a global scale. It cooperates with some application of this right. An important actor is

local governments and also with workers unions in again the Council of Canadians Blue Planet Project.

the public services in order to defend a public manage- Competing positions on the recognition and imple-

ment model and to profit from the workers technical mentation of this right are largely explained by two

skills and knowledge. The network Reclaiming Public opposite visions on water management. To its defend-

Water, established through the Transnational Institute, ers, the human right to water, both as regards to

supports and backs efforts to bring water management drinking water and sanitation, leads to management

back under public control.176 as a public service. As an inalienable right, water

Two ideas come to mind looking at the slogans management can hardly be under the control of the

of water activism campaigns (Table 3). On the one private sector, whose management criteria do not

hand, there is an emphasis put on water as source of necessarily respect solidarity, mutual cooperation,

life rather than as a socioeconomic asset. Besides the collective access, equity, democratic control, and

ostensible material challenge, conflicts for access to sustainability (Ref 181, p. 7).

550 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Volume 2, September/October 2015

WIREs Water Political ecology of water conicts

However, there is a vision of access to water ecology perspective. Political ecology studies who has

and sanitation linked to meeting increasing needs the power (by custom or law) to use the available

and ensuring adequate living standards, which the water from a river or to dig wells that reach the

state would set up gradually according to the levels water table excluding others. Do humans recognize

of economic development in each country.182 The the rights of nature, and are there court decisions

growth-based development models assume that needs determining the right of a river or a lake to have its

grow according to income, so this view of water morphology and its biological and chemical quality

management takes for granted raising water demands. unchanged? Who has the power to make a dam that

It has been argued that some transnational will flood farmland or forests, for the benefit of an

water corporations may have welcomed the idea of electrical company and to the detriment of the ripar-

a rights-based access to water, assuming that they ian inhabitants upstream and downstream? Which

would be the ones in charge of provisioning. Against decision procedures (CBAs, environmental impact

this vision, a (re)commonalization strategy is advised assessments, participatory MCEs) are valid to decide

instead.183 At the European level, the Italian referen- whether such a dam can be built? Are local referenda

dum 2 S per lAcqua Bene Comune in 2011 was a allowed against mining projects or privatization of

turning point pushing forward a new concept where water supply? Who has the power to determine the

water is considered as a commons, which should not process for reaching decisions on the alterations to the

be privatized and subject to monetary valuation.158 hydrosocial cycle? These are all questions of the polit-

On another level, in the practice of Andean ical ecology of water.

peoples, land, water, and air are also subject of rights, CBA was deployed in the assessment of river

in the perspective of deep ecology. The invocation basin development since the 1940s. However it is now

of the Pachamama is accompanied by the need to being put into question and participatory multicriteria

respect her, which translates into an ethical rule for approaches arguably can be used instead. When look-

the good of everything living and nonliving. Building ing at other methods capable to unveil the implications

on this tradition, the Article 71 of the Ecuadorian of water management for different types of groups,

Constitution184 stipulates that nature has the right water metabolism indicators reveal links between pro-

to be respected in relation to the maintenance and duction and consumption that allow tracing the direc-

regeneration of its vital cycles, structure, functions tion of VW flows in unjust patterns of trade, and can

an evolutionary processes. [Therefore, e]very person, be also used for raising consumer awareness. Taming

community, people or nationality can claim from the rivers to avoid the water getting wasted has been a

public authorities respect for the rights of nature. motto of hydraulic engineers. However, water is not

In this context, when public works for expan- lost; it contributes to the prosperity of riverine and

sion of the road Vilcabamba-Quinara in the South coastal areas. The ecosystem services approach allows

of Ecuador resulted in the disposal of large amounts grasping the multifunctionality of water ecosystems,

of rock and excavation material, a court case was and it also allows understanding of the conflicts for

brought up by Richard F. Wheeler and Eleanor G. the appropriation of these services.

Huddle, environmental activists, under article 71 of The emergence of water conflicts is related to

the Constitution. For 3 years, until 2011, the project changes induced in the availability of water in the

promoted by the provincial government was con- quantity and quality desired by rich and powerful.

ducted without environmental impact studies, increas- Everywhere in the world, communities fight not only

ing the risks linked to the floods of the Vilcabamba against dams and water transfers but also against

River during the winter rains. On March 30, 2011, mines, eucalyptus plantations or against energy crops

the Provincial Court of Justice of the city of Loja, rec- taking water from the villagers. Extractive industries,

ognizing the facts, made effective the constitutional including biomass, have spill-over effects on water

guarantee in favor of the plaintiffs, settling a historical quantity and quality. When social groups mobilize

precedent in fulfilling the rights of nature.150,185 Out- against such kind of projects that deteriorate the

side the scope of legal activism, moratoria have been quality and quantity of local water, they are fighting

argued as another tool for the application of Rights of for environmental and social justice and particularly

Nature.76 for water justice.

These struggles are a response to the worlds

economy growing metabolism. Certainly, neoliberal

CONCLUSION policy treats water as a commodity, as the aim of

This article reviews methodologies, types, and polit- private water operators is to generate profits rather

ical implications of water conflicts under a political than to ensure universal water rights and Nature

Volume 2, September/October 2015 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 551

Advanced Review wires.wiley.com/water

protection. Notice, however that the increasing use of NOTES

water is not just a product of neoliberalism, it is due a

The data-mining of suitable references started by

to the growth of the metabolism of the economy. This

using the search terms political ecolog* AND water

would happen also and indeed it happens under state

OR conflict* in Thomson Reuters Web of Knowledge

capitalism.

SM. 24/80 selected articles were highly relevant, from

Many mobilizations for water justice are merely

titles and abstracts. Then, additional studies were

defensive, facing specific threats of displacement or

identified in order to provide pertinent examples.

loss of access to livelihoods. However, the claims go

In this process, two types of gray literature were

beyond this. Water justice movements and organiza-

included: position documents and reports published

tions have formed networks, have proposed new prin-