Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nile Green Making Sense of Sufism' in The Indian Subcontinent: A Survey of Trends

Uploaded by

Abrvalg_1Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nile Green Making Sense of Sufism' in The Indian Subcontinent: A Survey of Trends

Uploaded by

Abrvalg_1Copyright:

Available Formats

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.

Making Sense of Sufism in the Indian

Subcontinent: A Survey of Trends

Nile Green*

University of California, Los Angeles

Abstract

This article provides a summary of developments in recent decades in the study

of Sufism in South Asia (referred to here as the Indian subcontinent). Beginning

with the highly influential formulation of Sufism as Islamic mysticism, it analyses

the serious shortcomings of this category, before moving on to assess the impact

of anthropological, socio-historical and post-structuralist approaches to Sufism in

the subcontinent. A final section considers issues surrounding the roles of the

Sufis in the relationship between Islam and Hinduism. In pointing to areas that

have not been investigated as well as those that have been, the article aims to be of

use to graduate students seeking research projects as well as undergraduates and

scholars from other disciplines seeking an overview of the field.

The Dilemmas of Definition

One of the perpetual dilemmas of scholarship is the creation of descriptive

or analytical categories to define the phenomena that scholars observe in

their data. When such categories are accurate and pertinent, they enable

us to understand quickly and holistically the phenomena to which they

apply and to relate these phenomena to features of the world around them.

The opposite is also true: inaccurate or impertinent categories conceal

aspects of what they are meant to elucidate and confuse us when we try

to understand the connections of the phenomena in question to their

surroundings. In the study of religions, a good example of this is the

category of Sufism, a term first used by such British soldier-scholars as

Sir John Malcolm and James William Graham in the early 1800s (Ernst

1997, pp. 818) and today by academic and increasingly non-academic

commentators on the Islamic world. This article looks at how scholars

have used this category in recent decades and at the problem of relating

it to the phenomena that it does, does not and at its weakest cannot

explain. In doing so, it also offers a survey of the different ways in which

Sufism has been studied by scholars working on India since the midtwentieth century as an overview of the academic literature on Indian

Sufism for those new to the field.

2008 The Author

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Making Sense of Sufism in the Indian Subcontinent 1045

Without dwelling too long on the matter, it is important to recognise

the degree to which scholars in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

laid emphasis on explaining the origins of Sufism. Indeed, the most controversial question in the study of Sufism among scholars trained before

around 1950 concerned the sources from which Sufi traditions developed,

as though solving this question would help explain the later relationship

of Sufism with the wider body of Muslim tradition. To put the matter in

its simplest terms, there were two basic strands to the debate, one pointing

towards an origin inside Islam and one arguing for the external origins

of Sufism. As academic and political sensibilities changed, various models

were put forward to explain these alternatives, ranging from racial theory

(mystical speculation characterized Aryan races like the Persians rather than

Semitic peoples like Arabs) to the quest for influences that characterised

the school of comparative religion (similarities between Vedantin and

Sufi doctrines suggested the impact of one on the other). Thus, in her

reconstruction of the Christian monastic milieu of the Fertile Crescent in

the early Islamic era, the comparatist Margaret Smith (1931) presented

evidence for the transference of Eastern Christian ascetic techniques and

doctrines into early Sufism, while three decades later another comparatist

R. C. Zaehner (1960) reframed the arguments of Max Horten (1927

1928) to claim an Indian origin for pantheistic Sufism through the

somewhat flimsy evidence for the existence of an Indian teacher instructing

the early Sufi Abu Yazid Bistami (d. 875). Opposing this trend which

in origin at least had more than a little of the tendency to belittle the

creativity of the Arabs and their austere religion of the desert the

distinguished French Islamicist Louis Massignon (1922) used a refined

method of historical philology in an attempt to prove that Sufi doctrines

had emerged organically from the Quran by means of meditation on and

the subsequent semantic expansion of its vocabulary. As the twentieth

century wore on, for many scholars the debate seemed to have run out

of steam, not least with the decline of traditional Orientalist patterns of

scholarship in which the identification of origins and classical formulations

of religious or cultural forms had been prioritised. In recent years, several

scholars have returned to the debate, most thoroughly in the case of Julian

Baldick (1989), who has leaned towards a moderate version of the external

influence argument, particularly with regard to Eastern Christianity, and to

a limited extent, also with regard to Shamanistic and Sanskritic traditions.

One of the most influential scholars to argue for an Islamic source for

Sufism was the Cambridge academic A. J. Arberry. A key element in

Arberrys defence of the internal origins of Sufism against the diffusionist

models of the comparatists was the model of Sufism as an Islamic expression

of universal mystical experience. This formulation has proven the most

enduring definition of what Sufism is, its very effectiveness coming partly

from its ability to side-step the earlier debates over the specific origins of

Sufism by pointing towards multiple points of origin in an innately human

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

1046 Nile Green

impulse. In the opening page of the introduction to his influential textbook

Sufism, first published in 1950, Arberry offered what by the middle of the

twentieth century he felt could be regarded as an uncontroversial definition

of Sufism as the name given to the mysticism of Islam (Arberry 1950,

p. 11). For many commentators this still serves as their definition of

choice today. The problem is that as Islamic mysticism the category of

Sufism relies for its explanatory power on another category that is no less

problematic: mysticism. As Arberry saw the matter, mysticism is essentially

one and the same, whatever the religion professed by the mystic . . .; even

though it possessed variations influenced by the different religious systems

in which it was based, mysticism is undoubtedly a universal constant

(Arberry 1950, pp. 11, 12). Again, many people would be inclined to agree

with this today, begging the question why mysticism is so problematic a

category as to undermine the explanatory power of Sufism. The problem

lies in the fact that the concept of mysticism is not nearly as universal as

Arberry and others would have it. Indeed, its origins scarcely stretched

further back than a century before Arberry himself was writing, and insofar

as there was a one and the same involved in mysticism, it was that the

people discussing and defining it were other ecumenically minded European

intellectuals very much like himself (Christmann 2008). Certainly, there

were also non-Europeans who joined in the polite chatter. Quite a number

of Muslims as well as Hindus and Buddhists (many from parts of the world

exposed to European ideas through colonialism) voiced their agreement

that, despite the apparent strangeness of their traditional beliefs and practices,

at heart the teachings of their traditions were one and the same as those

that the European professors promoted as the highest endeavour of religion:

an individual, unmediated experience of the divine typically experienced

as a feeling of unity and commonality with all creation. In a word,

mysticism.

The problem is that the category of mysticism is at heart a theological

one and, we might choose to add, an ideological one as well. It is theological

in the sense that it takes as its premise the existence of a primordial entity

(whether god, being, love or primordial experience), which it uses to explain

ideas and actions in the human world. It is ideological in the sense that

it is a truth claim that posits certain attitudes or actions towards the

surrounding world, such as tolerance of difference, the creation of certain

forms of social organisation (inter-faith meetings, a World Parliament of

Religions) or even the radical politics of utopianism. For those of us who

would prefer to live in a harmonious and tolerant society, the promotion

of these theological or ideological attitudes is probably something to be

grateful for. But the scholar or student of religion is not someone whose

training is primarily aimed towards the hastening of the Age of Aquarius.

On the contrary, the scholar of religion is trained to analyse the phenomena

of religion as it is (or was). With its focus on the individual, on experienced

(as opposed to mediated) religion and on the lofty ideas, sentiments and

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Making Sense of Sufism in the Indian Subcontinent 1047

motivations of an elite cadre of mystics rather than the literalism and

superstition of the orthodoxy and the masses, the mystical subcategory

of Sufism fails to explain many of the phenomena brought under its label.

As a result, the existence of collective and kin-based Sufi organisations,

the huge popularity of dead Sufis acting as saintly mediators and the more

general fact that by the medieval period this form of Sufism had become

the religion of the Muslim masses found themselves pushed into the

marginal conceptual order of popular Sufism.

This failure of explanation brings us to the key problem with mysticism

as a category and of Sufism conceived as a subcategory thereof. For

when confronted with data about the actual mystics or Sufis who were

presumably meant to embody the elevated ideals of mysticism and Sufism,

the paired categories run into trouble. When Europeans first discovered

Sufism in the nineteenth century through reading Arabic and Persian

texts, they were faced with the perplexing contradiction that the living

Sufis they were introduced to in India and Persia seemed to display anything

but the humble, generous and ecumenical characteristics of the genuine

mystic. On the contrary, the men to whom they were introduced (and

they mostly were men) were wealthy land-owners haughty with the

admiration of their followers who were in many cases of anything but an

ecumenical disposition towards their new Christian rulers or else they

were the semi-literate beggars and fakirs European travellers denounced

as charlatans. When such Sufis failed to live up to the elevated sentiments

described in the writings of their medieval forbears, European scholars

came up with what seemed to them a convincing explanation: Sufism

had clearly declined from its medieval apogee. The explanatory power of

this picture of decline was strengthened by its harmony with a colonial

agenda in which the decline of Asian institutions helped justify the rule

of Europeans (who were in contrast seen as entering their civilisational

zenith). When Muslim intellectuals in India and elsewhere sought to explain

the ease with which their societies had fallen under European control,

decline theory also proved useful to them, especially when it could be

linked to a remedial call for renaissance or renewal (nahda, ihya, tajdid),

usually along lines directed by the Muslim intellectual in question. These close

connections between the conceptions of Christian (particularly Protestant)

Orientalist scholars and Muslim reformers are also seen in the other key

implication of the mysticism and decline model, that the whole gamut

of cultural phenomena from miracle stories and shrine veneration to the

biological inheritance of Sufi gnosis and the high pomp of the Sufi orders

could be interpreted as something fundamentally different from the

essential or original nature of Sufism. According to the agenda or

inclinations of the observer, such phenomena were instead classed as

superstition, reprehensible innovation (bida), folk religion or (in a halfhearted attempt to use the insights of Max Weber) as the routinisation of

charisma through the institutionalisation of the Sufi order. Through this

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

1048 Nile Green

implied dichotomy between high and low, elite and popular, the old

paradigm of mysticism and decline was perpetuated by transforming the

chronological into the diachronic: decline did not occur at a certain

moment in time because high and low forms of religion were characteristic

of all periods. Although scholars of religion have disassociated themselves

from the old dichotomies of high/low and popular/elite, in practice the

gap between a Sufism of poetry, texts and high theory and one composed

of miracles, rituals and filthy lucre continues to characterise the study of

the Sufis of India and elsewhere. Even if the gap is no longer reified as a

dichotomy, its legacy remains as a hole in the middle of our understanding

that prevents us from gaining a more holistic picture of the phenomena

of Sufism.

Through its reliance on an abstract ideal of mysticism that few if any

real historical people could live up to, the category of Sufism had allowed

theology to serve as the judge of history. To make matters worse, the

perception of a Sufi decline became self-perpetuating, as the concentration

of research on the classical age meant that the Sufis of later centuries

were by-passed because they had nothing new to say; and because these

later Sufis were by-passed there was little evidence found to counter the

model of decline. Even in 1950 with a wealth of earlier scholars work

behind him, Arberry was able to end his survey of Sufism in 1273 with

the death of the Persian poet Jalal al-din Rumi. He only referred to later

Sufis in a final chapter entitled The Decay of Sufism in order to demonstrate

how as soon as legends of miracles became attached to the names of the great

mystics . . . the cult of the saints . . . promoted ignorance and superstition

(Arberry 1950, p. 119). With its virulent antagonism towards miracles and

sainthood, not only was Arberrys account of Islamic mysticism a theological

reading of the past, it was also a decidedly Protestant one. Once again, this

reflected the ideas of Muslim modernists and reformers, whose gradual

reformation of Islam into a rational and disenchanted religion was to

strongly influence twentieth-century Indian Muslim scholars, whose

presentation of Indias Sufis has long been characterised by a focus on

classical medieval figures and on materials showing them as teachers and

intellectuals rather than superstition-mongers and miracle-workers. Scholarship

thus abounds that focuses on the great Sufis of medieval Delhi and on the

idea of the authentic malfuzat (recorded conversation) genre as representative

of the modernist Muslim ideal of the teaching (rather than miracle-working)

shaykh. Again, this was a tendency shared by European and American

scholars, shaping the perceptions of even those trying to advance the study

of the Sufis in historical terms. When J. Spencer Trimingham published

his highly influential The Sufi Orders in Islam in 1971 in an attempt to

better contextualise the evolution of Sufi thought and practice in the

times and places of history, the thirteenth century was still regarded as a

turning-point towards decadence and decline. Still, for all its problems as

a sophisticated exercise in history-as-decline, Triminghams Sufi Orders has

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Making Sense of Sufism in the Indian Subcontinent 1049

a great deal to recommend it and in its recognition of the contributions

of Indian and African Sufis and of the Sufi revival movements of the

eighteenth century it was a book that was in many ways ahead of its time.

Placing the Sufis into Society

As the Victorian locomotive of mysticism ran out of steam in the 1970s,

there emerged a new approach to the study of Sufism. This change had

its roots in the prestige of the social sciences among academics of the

1960s generation and its effect was to reconfigure the study of Sufism as

an exercise in either social anthropology or social history. Rather than

deplore the institutionalisation of Sufism into orders (turuq, sing. tariqa)

and cults of the Sufi saints (awliya, sing. wali), it now appeared important

to understand the work that such activities accomplished in the societies

where they flourished, even (or especially) if this meant substantially

rejecting the notion of Sufism as mysticism. Among the anthropologists,

it was North Africa rather than India that was the main testing-ground

for this new way of looking at Sufism and it was there that two of the

most important of these early works, Clifford Geertzs Islam Observed (1971)

and Ernest Gellners Saints of the Atlas (1969), were based. When Gellner

came to summarise his ideas about Muslim societies in the early 1980s,

he was able to entirely eschew the mystical paradigm and declare with

regard to the origins of Sufism that the most important factor, at least

sociologically, seems to be the inescapable requirement of religious organisation

and leadership (Gellner 1981, p. 103). For in the absence either of the

urban infrastructure required to promote the Islamic law schools or of a

strong state, Sufism provides a theory, terminology, and technique of

leadership (Gellner 1981, p. 103). For Gellner it was neither here nor

there whether the hereditary saints of the Atlas mountains taught their

followers a direct way to experience God. What was more important was

that they and their equivalents in other parts of the Islamic world provided

their surroundings with the order and organisation that allowed them to

function as societies. While the methods of both Gellner and Geertz have

been criticised, in their use of the techniques of the social sciences to make

sense of practices that earlier scholars could only dismiss as popular religion

or superstition they broke the new ground in which others would in turn

sow new seeds of interpretation. Since the 1980s, the anthropological

study of Sufi practice and of Muslim practice in the subcontinent more

generally has become well-established and a good sample of the range of

questions anthropologists address can be found in a recent anthology that

prioritises the ethnographic observation of actual Muslim practice over the

prescriptive tendencies associated with the older prioritisation of mystical

criteria (Ahmad & Reifeld 2004). The ethnographic focus on the external

playing out of religious practice has opened up new perspectives on the

dynamism of every aspect of Sufism, whether through the study of saint

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

1050 Nile Green

cults at the level of the Indian village (Assayag 1995) or of the transformation

of Sufism by trans-nationalism and globalisation (Werbner 2003). Nonetheless,

perhaps the most successful attempt to relate popular practices in the

subcontinent and elsewhere to an Islam of writing and theory was

the phenomenological reading that, through her unrivalled knowledge of the

diversity of Indo-Muslim and particularly Sufi traditions, Annemarie

Schimmel (1994) was able to give in her Deciphering the Signs of God. If it is

a book that was wilfully out of step with anthropologising or historicising

fashions, it remains a valuable attempt to synthesise the plurality of popular

Muslim practices into a dignified and coherent set of patterns.

The insights developed by anthropology and sociology into the decadent

or popular practices that were marginalised by the mystical school bore

rich fruit in other fields of the study of religion by also helping scholars

re-imagine the past in new ways. The most influential of these was not

an Islamicist at all but a historian of Christian Late Antiquity, Peter

Brown, whose reading of Ernest Gellners account of the Muslim Saints

of the Atlas helped him to formulate a radical new interpretation of the

early Christian saints, now dubbed as holy men. Brown re-envisaged the

social world of such holy men as Simon Stylites (d. 459) as the Roman

administration crumbled as comparable to that described by Gellner in the

Atlas mountains of Morocco in which a holy man could act as an arbiter

in the public disputes that inevitably characterised such fractured societies.

Here holiness was seen in sociological terms as being born from the holy

mans position as a social outsider that allowed him to intervene in everyones

business with apparent impartiality (Brown 1971). The revolution that

Browns work set off in the socio-historical study of Christian saint cults

(institutions that were themselves long marginalised as the cultural nadir

of post-classical Europe) gradually made its influence felt in the study of

Sufi saints and holy men. Whether the stories of a Sufis miraculous

powers bore any relationship to mysticism now did not matter: what

was more important was that they served social (or, later, cultural)

purposes that scholars could investigate. In terms of the study of the

Islamic world, this new recognition of the uses of superstition opened

up vast new areas in which social historians could work. With Sufis now

freed from being tested on a scale of compliance to the authentically

mystical, a new generation of historians was able to assess the other

activities in which these figures were involved when they were not pursuing

union with God (if indeed they were at all). Although the social was

sometimes interpreted in terms of the narrowly political, this approach

proved extremely influential among historians of India, reinvigorating an

older school of social history that had tended to mine hagiography for

steely facts rather than the subtler stuff of mentalities and meanings (however

for valuable examples of this older trend, see Nizami 1961; Askari 1976;

Islam 2002). The most original early example of this new trend was Richard

M. Eatons Sufis of Bijapur, which extrapolated a series of social roles that

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Making Sense of Sufism in the Indian Subcontinent 1051

Sufis played in the South Indian sultanate of Bijapur between 1296 and

1686. Alongside such well-known activities as moralising and writing

books, the most controversial of these roles was that of fighting in the

armies of the sultan. Eaton had brought the figure of the mystic full

circle: from the ecumenical friend of all faiths he had become the violent

slaughterer of unbelievers. Given the role that, ever since the publication

of Thomas Arnolds The Preaching of Islam (Arnold 1896), the Sufis had

played in the modern Indian imagination as peaceful, singing proselytisers

of a gentle Islam, to many the idea of a warrior Sufi was both anathema

and oxymoron (Nizami 1979).

Around 15 years later, Eatons evidence was tested in a work that tried

to bring the techniques of the social historian together with a recognition

of the literary turn among the cultural historians of the 1980s that was

demanding scholars pay greater attention to the rhetorical strategies of

their sources. In his study of the Sufi circles of Khuldabad, some way to

the north of Bijapur, Carl W. Ernst (1992, pp. 95105) argued that Eatons

source materials are much later than the events that they supposedly

describe and so reflect less actual events than later re-imaginings of the

spread of Islam written under the influence of the Mughal empire.

Whichever side of the argument one comes down on, Ernsts approach

was part of a wider academic shift towards the more careful location of

Sufi writings within the discursive no less than social contexts that had

produced them. From now on, it would no longer be enough to lift ones cap

to the interplay between religion and politics (categories that dominated

the work of K. A. Nizami 1961 and his many followers) but rather to see

how the phenomena previously denominated by these categories were

intrinsically bound together, seeing Sultans and Sufis as competing for

control of the same symbols, and behind these symbols, for the same

limited pool of legitimacy and power (cf. Ahmad 1962; Alam 2004).

In some respects, Ernsts special interest in the actual teachings of the

Khuldabad Sufis was a continuation of the emphasis on doctrine that

characterised the older mystical school. But instead of assuming that the

Sufis were trying to give voice to an experience that was essentially one

and the same as that of other mystics in other times and places, Ernst

emphasised the distinctive characteristics of the Khuldabad Sufis. And

instead of seeing their promotion of an organised Sufi order and their

connection to the courtly personnel of the Delhi sultanate as symptomising

incipient decadence, he presented the Sufi as a moralist, unable to escape

the murky realities of his social existence but perpetually anxious to avoid

being compromised by them. Here as in other writings, Ernsts emphasis

on the ethical dimension of Sufism helps bridge the gap between doctrine

and social practice that has long separated scholars of the mysticism and

social history schools, for the etiquette and ethics (adab and akhlaq) with

which so many Sufis were concerned in both writing and living form the

point at which the ideal and material dimensions of their lives intersect.

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

1052 Nile Green

By not losing sight of the religious dimensions of the Sufi tradition (as

the functionalism of certain anthropologists and social historians was wont

to do), while at the same time placing the Sufis in their political contexts,

Ernst and his collaborator Bruce Lawrence (2002) have been able to paint

a picture of the Chishti tradition of Sufism as a credibly fallible human

project handed down in a recognisably real world.

The Return to the Text

The greater attention towards the rhetoric of Sufi writings shown by

Ernst and Lawrence has been reflected in a number of other studies since

the 1990s. After the social historical fashions of the 1970s and 1980s, a

particular characteristic of this return to the text was the new degree of

attention given to hagiographical works. The legacy of the old mysticism

and decadence approach meant that scholars had long neglected such

texts, whether from India or other parts of the Islamic world. Since the

production of such hagiographies (tazkira, tabaqa, manaqib) often outnumbered

that of books of doctrine, vast numbers of neglected texts were (and still

are) available for either fresh study or reappraisal. Although the ascendance

of social history had already led a large number of scholars most notably

Simon Digby (2004) and K. A. Nizami (1961) to carefully sift such

hagiographies for information on the Sufis relations with wider society,

it was now the texts themselves that were of interest. A new wave of literary

studies used hagiographical as well as poetical works to address such processes

as identity formation, memory and the creation of hybrid religious forms

(Hermansen 1988; Shackle 1999; Hermansen & Lawrence 2000; Stewart

2001). The re-evaluation of long-neglected genres in turn allowed historians

to use such texts to look in fresh ways at socio-religious practices like

pilgrimage (Digby 1983; on Egypt see Taylor 1999), while on the more

literary side interesting work (Behl 2005) has also been produced addressing

narrativity as a broker of the syncretism more frequently encountered in

anthropological studies. In other cases, the textual turn has itself come full

circle, with a growing number of scholars attempting to see Sufi writings

as part of the process of history, by asking what such texts did in the

social world, whether as the hardware of memory or as the portable

coffers of tradition (Rinehart 1999; Green 2006).

This trend reflects wider developments in the study of South Asia more

generally, in which a twin attempt to historicise texts and textualise

history is being made in many different sub-fields as part of the effort to

work out what exactly it is that our written sources tell us (Inden 2000).

In time, we can hope that this approach might reassess the longstanding

shibboleth of the pervading influence of the Sufi doctrine of the Unity

of Being (wahdat al-wujud) in shaping the beliefs and practices of Indian

Islam. Until we can map how this doctrine spread from the treatises and

commentaries written by scholarly Sufi to the ordinary people, then the

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Making Sense of Sufism in the Indian Subcontinent 1053

purported scale of its influence must remain conjecture. A good start has

been made here in a short article by William Chittick (1992), but much

work still remains to be done that must bridge the gulf that still separates

the elite realm of philosophical doctrine from the popular realm of most

of Indo-Muslim society (Green 2006). Apart from the eighteenth-century

dars-e-nizami syllabus (Robinson 1993a), we still know far too little about

the reading habits and book collections of Indias Muslims in general, let

alone of the Sufis. The problem here is that with a few notable exceptions

(e.g. Seyller 1997), book history has yet to really make an impact on the

study of Islamic India, despite the recent advances made for other regions

of the Islamic world (Messick 1993; Bloom 2001; Hanna 2003). Until we

are able to clarify such basic issues as the relative costs and availability of

manuscripts, levels of literacy, and access to the languages (like Persian and

Arabic) in which premodern Sufis largely wrote (except for poetry), then

we will remain unsure as to exactly whose world our sources allow us to

enter. A related problem has emerged from the old emphasis on medieval

classics, which led to the training of generations of scholars in the classical

or Islamic languages of Arabic, Persian and to a lesser extent Urdu in

preference to the wide range of other languages that Sufis have used.

While the Sufi contribution to poetry in the vernaculars was championed

in the many pioneering studies of Annemarie Schimmel (see, for example,

Schimmel 1975), work on Sufi prose writings in such languages as Bengali

(Cashin 1995), Marathi (Dek 2005) and Dakani (Suvorova 2000) suggests

that other very different Sufi lifeworlds remain to be explored. In recent

years, this change of linguistic emphasis has certainly been under way, and

in some respects the shift towards the vernacular has undercut the study

of the classical languages by younger scholars working on India, such that

Indian Arabic works now ironically receive less attention than Muslim

writings in Gujarati.

Neglected Centuries: Sufis from 1700 to 1900

A similar pendulum swing can be detected in the move from the old

concentration on the classical Sufis of the medieval period towards the

study of Sufi movements from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

With the longstanding interest of the colonial period to scholars in both

the subcontinent and the West, it was only a matter of time until the

interest in the Muslim revivalist and modernist movements trickled down

into an interest in the less famous Sufis of the nineteenth century. The

two major movements Deobandi and Barelwi that mark the main

parameters of religious reform as it related to the Sufis have been particularly

well-scrutinised (Metcalf 1982; Sanyal 1996). But while reform and the

response to it continues to dominate the academic agenda for this period

not least as a result of the paper trail left by the reformists embrace of

the printing press (Robinson 1993b) there are still important areas that

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

1054 Nile Green

remain obscure. In an important study of colonial Sufis from outside the

spotlight, Art Buehler (1998) has examined in detail the rise of what he

posits as an ascendant institution in this period, that of the mediating

shaykh. But many other questions remain: what happened to the antinomian

faqir and qalandar Sufis during this period, for example, and in what ways

were Sufis able to re-organise themselves in Indias new industrial cities?

In what remains the only attempt at a comprehensive history of Indian

Sufism (Rizvi 1978 & 1983), coverage of developments after 1700 is very

uneven and after 1850 almost non-existent. What studies do exist of the

nineteenth century tend to foreground the impact of colonialism and

while British rule undoubtedly ruptured many areas of Indo-Muslim life

there remains work to be done on the Sufis who continued to be patronised

in the independent princely states as well as the survival of Sufi networks

connecting Muslims in colonial India with Iran, Afghanistan and Arabia.

In comparison to the nineteenth century, coverage of the eighteenth

century is more patchy. Having fallen between the catchment areas of

medievalists and modernists, the eighteenth century was always a neglected

area in Islamic and Indian studies, though the fact that the eighteenthcentury witnessed the careers of several influential Sufis means that we do

have important studies of such individual figures as Shah Wali Allah (Rizvi

1980; Baljon 1986) and of Khwaja Mir Dard of Delhi and Abd al-Latif

of Bhit in Sind (Schimmel 1976) and of the Deccans Sufis who flourished

under the late Mughals and Nizams of Hyderabad (Green 2006). But even

in the best attempts to position the Sufis of the eighteenth century into

their wider intellectual and social contexts (Umar 1993), as with the study

of the nineteenth century the geographical focus has largely remained on

Delhi and Lucknow. Even for any period, we still know startlingly little

about the Sufis of such major cities as Peshawar, Lahore and Ahmadabad,

let alone those of the more routinely neglected cities of the southern and

eastern regions of the subcontinent.

The Physical Dimensions of Spirituality

We have already discussed one trajectory of the influence of what we can

broadly term as postmodernism in the greater emphasis given to textuality,

but another (and in the Indian case more recent) trajectory has emphasised

the physical dimensions of Sufi practices as ways of disciplining the body

or embodying the abstractions of doctrine. This trend was first apparent

among anthropologists (Basu & Werbner 1998), but more recently has also

been taken up in different ways by those working with Sufi texts (Kugle

2007; Green 2008). This focus on the physical dimensions of Sufi tradition

has also joined up with research on such areas as traditional medicine and

healing (Burkhalter Flueckiger 2006), work that has helped out-step the

older and more static paradigm of ritual. Nonetheless, valuable work still

continues to be produced with regard to Indian Sufi practices, not least

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Making Sense of Sufism in the Indian Subcontinent 1055

in connection to the mahfil-e-sama or formal musical gathering, as

demonstrated in a recent collection of essays examining sama in different

periods (Huda 2007). In the field of ethnomusicology, other investigators

have explored the performative aspects of Sufi musical traditions and their

relationship with issues of gender (Qureshi 1986; Abbas 2002). Greater

attention towards the physical aspects of Sufi life has also begun to pay

dividends through the study of Sufi material culture, though given the vast

potential for research in this field it is surprising how little work has been

done. Jrgen Frembgens pioneering survey of dervish paraphernalia

(Frembgen 1999) does, however, contain a good deal of material from the

subcontinent and we can hope that greater recognition of the importance

of objects to the world-renouncing mystics will enrich future textual no

less than ethnographic studies. In terms of the study of the Sufi shrines

that number thousands in India, there are two edited volumes of note

(Troll 1989; Currim & Michell 2004). But the legacy of the shrines

association with decadent saint-worship through the routine neglect of

this area means that many scholars still study Sufism with only the haziest

notions of the physical environments in which its practitioners operated.

Compared to the careful architectural surveys and documentary analyses

that have been carried out for Sufi buildings and other Muslim shrines

elsewhere (Golombek 1969; Fernandes 1988; McChesney 1991), this area

of research is still in its infancy in India. The private archives held by

scores of such shrines across the subcontinent offer vast potential for such

architecturally grounded histories of Sufi practice.

Sufis Between Muslims and Hindus

Finally, no survey of the study of Indias Sufis would be complete without

addressing the question of syncretism and the Sufis role as mediators

between Muslims and Hindus. Perhaps more than with regard to any

other aspect of Indias religious culture, our understanding of the processes

at work here has been distorted by the gravitational pull of the weighty

ideological bodies that surround the matter. The combined influence of

monolithic nineteenth-century formulations of religion, the neat (but often

anti-historical) distinctions of the World Religions model and the assertions

of difference made by both Hindu and Muslim religious nationalists has

allowed stark modern formulations of religious identity to be seen as a

permanent fixture of the Indian past. Scholars of Hinduism have shown

with considerable success that the notion of such a single pan-Indian

religion was an invention of the nineteenth century (Fitzgerald 1990), and

a result the study of Hindu religious history is now buzzing with discoveries

of the distinct temporalities and localities that shaped the Hindu religions

(Saberwal & Varma 2005). In the case of Islam, we have yet to reach the

critical mass of scholarship needed to assess how in the different times and

places of Indias past those whom we call Muslims (and in so doing

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

1056 Nile Green

foreground a monolithic religious identification) did actually identify

with the body of ideas and practices that we call Islam. The ideological

influence of pan-Islamism on Muslim and non-Muslim minds continues

to encourage a unitary and uniform perception of Islam that is difficult

to think around. There is, however, much evidence to suggest that the

more common Indian use of the term Musulman in place of Muslim

actually referred to something more like a kinship or caste-like identity, so

that it was quite possible to be a Musulman and a Yogi without experiencing

the kind of clash of categories that would present itself to the modern

observer. Here the work of Richard Eaton (1993) on the transition

between religious identities in Bengal and of Dominique Sila Khan (2000,

2003) on liminal and localised religious identity and activity offer exciting

possibilities for deconstructing the old paradigm of Islam as a monolithic

World Religion.

However, much of the work in this field is based on ethnography and

as such presents problems for those interested in the earlier history of such

patterns of behaviour and identification. Because so little of the real sociohistorical groundwork has been done, the old model of syncretism (i.e.

of two distinct entities meeting) on which so much research has been

predicated means that we may have long been getting the horse before the

cart, asking how was it that Hindus and Muslims could come together

when the people we label under these terms had perhaps not yet come to

see themselves as apart in the first place, at least in terms of a doctrine and

practice model of religion (Green & Chatterjee 2008). As anthropological

commentators have recognised for some years (Stewart & Shaw 1994), the

model of syncretism prioritises and even primordialises the existence of

distinct social groups or religious entities (here, Hinduism and Islam) whose

existence may not have been recognised by the actual people concerned.

Since self-identification with a trans-regional religious community has

certain historical preconditions (not least access to the communication and

knowledge systems that afford awareness of such distant and so by definition

imagined communities), it is by no means clear whether the majority of

people in Indias past identified themselves primarily or at even all in these

monolithic, binary or uniform religious ways. In this case, as a heuristic

device we may as well throw the model of religion to one side and look

instead at region, language, kinship, economy or even technology as more

efficient ways to understand what we tend to automatically think of as

religious phenomena. Thus, when investigating the popularity of a given

Sufi, we may do better to interpret his success among Muslim and

Hindu followers as a reflection of his ties to particular kinship groups,

who think in a local language world in which Hinduism and Islam

(or even religion) do not exist as concepts and in which the Sufi in

question is a major landholder whose family shrine acts not only as the

market-cum-pilgrimage centre of the region but also as the provider of

the technology of written documents and the medicine of talismans. The

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Making Sense of Sufism in the Indian Subcontinent 1057

best and earliest example of this kind of approach is Richard Eatons

(1984) study of the shrine of the great Punjabi Sufi, Baba Farid (d. 1265),

though here too it is Islam that dominates the conceptual picture.

Such perspectives suggest that what we understand by the term Sufism,

whether in terms of doctrines, books or the search for enlightenment,

may have little to do with the success of a given Sufi, whose social

identity among his followers may have been conceived in a variety of

other ways. As Carl W. Ernst (1997, p. 18) has noted, in Arabic and Persian,

there are dozens of terms for Muslim mystics with distinct and sometimes

conflicting meanings, all of which are subsumed by the English word

Sufism. This diversity of names, and as such of identity markers, was still

more abundant in the linguistic multiplicity of the subcontinent. In a great

many cases in India even today, those whom outside observers would label

Sufis are termed simply as baba (father) by both their Hindu and Muslim

followers, such that their identification with a reified or abstract system of

Sufism or Islam is not given precedence and may not even be recognised.

By the same token, until the nineteenth century Hindu Yogi masters were

widely addressed with the Persian Sufi title pir. To turn back to the issue

of categories with which this article began, the moral of the tale here is

that we need to be extremely careful about projecting the neatly packaged

categories like Sufism (or even Islam or religion) onto other times and

places. What looks to the outside observer like a Sufi Muslim (with all

that that implies) may have been conceived by his followers as simply a

baba, a supernaturally protective father-figure or patron, in the same way

that what looks like a Yogi Hindu may have been conceived as a pir and

as such a man of supernatural power with more in common with other

(Muslim) pirs than with ordinary Hindus. Here religion is less the theological

system of dogmas shared between adherents of ultimately global World

Religions than it is the product of small-scale allegiances based on the

face-to-face reciprocity of protection and devotion. From a universalising

Sufism based on written theories of mystical abstraction, we have come

to a localizing Sufism based on human bodies in emotional contact.

Conclusions

Over the previous pages, we have looked at many though by no means

all of the patterns that have directed academic understanding of Indias

Sufis during the past half century. It is important to recognise that most

of these trends are still alive and well: academic approaches rarely disappear

entirely but just slip from the spotlight, from where they continue to

interact with those currently on centre stage. As in any other area of

academe, there are also important regional traditions or schools and in an

article commissioned to point towards English-language sources it is inevitable

that Anglo-American perspectives have dominated the discussion. Hopefully

though, what we have provided is an overview of the different ways in

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

1058 Nile Green

which Sufism has been studied, as well as some of the areas that remain

open for graduate students and scholars from other areas beginning new

research projects.

Short Biography

Nile Green is an Associate Professor in the history department at UCLA.

He was previously Lecturer in South Asian Studies at the University of

Manchester and Milburn Research Fellow at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford

University. His research focuses on the history of Islam in South Asia,

particularly on the social and political history of Indian Sufism. However, he

has also written on Indo-Islamic reform, the history of objects, Muslim

travellers, oral and subaltern histories, the ethnogenesis of the Afghans,

the history of dreaming, and the politics of meditation. In addition to

many articles and book chapters, his publications include Indian Sufism

since the Seventeenth Century: Saints, Books and Empires in the Muslim Deccan

(London & New York: Routledge, 2006), a co-edited (with Mary SearleChatterjee) collection of essays entitled Religion, Language and Power

(New York: Routledge, 2008), and Islam and the Army in Colonial India

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Note

* Correspondence address: Nile Green, Department of History, University of California, Los

Angeles, Bunche Hall, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1473, USA. Email: green@history.ucla.edu.

Works Cited

Abbas, SB, 2002, The Female Voice in Sufi Ritual: Devotional Practices of Pakistan and India,

University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Ahmad, A, 1962, The Sufi and the Sultan in Pre-Mughal Muslim India, Der Islam, vol. 38,

nos 12, pp. 142 53.

Ahmad, I, & Reifeld, H (eds), 2004, Lived Islam in South Asia: Adaptation, Accommodation and

Conflict, Berghahn Books/Social Science Press, New York, NY/Delhi, India.

Alam, M, 2004, The Languages of Political Islam: India, 1200 1800, University of Chicago Press,

Chicago, IL.

Arberry, AJ, 1950, Sufism: An Account of the Mystics of Islam, George Allen and Unwin, London, UK.

Arnold, TW, 1896, The Preaching of Islam: A History of the Propagation of the Muslim Faith, A.

Constable and Co., Westminster, CO [reprinted numerous times].

Askari, SH, 1976, Maktub and Malfuz Literature as a Source of Socio-political History, Khuda Bakhsh

Library, Patna, India.

Assayag, J, 1995, Au Confluent de deux Rivires: Musulmans et Hindous Dans le sud de Linde, Presse

de lcole Francaise dExtrme-Orient, Paris, France; translated as At the Confluence of Two

Rivers: Muslims and Hindus in South India, Delhi: Manohar Publishers, 2004.

Baldick, J, 1989, Mystical Islam: An Introduction to Sufism, I.B. Tauris, London, UK.

Baljon, JMS, 1986, Religion and Thought of Shh Wal Allh Dihlaw, 17031762, E.J. Brill,

Leiden, The Netherlands.

Behl, A, 2005, The Magic Doe: Desire and Narrative in a Hindavi Sufi Romance, circa 1503,

in RM Eaton (ed.), Indias Islamic Traditions, 7111750, pp. 181208, Oxford University

Press, Delhi, India.

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Making Sense of Sufism in the Indian Subcontinent 1059

Bloom, J, 2001, Paper before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World, Yale

University Press, New Haven, CT.

Brown, P, 1971, The Rise and Function of the Holy Man in Late Antiquity, Journal of Roman

Studies, vol. 61, pp. 80 101.

Buehler, A, 1998, Sufi Heirs of the Prophet: The Indian Naqshbandi Brotherhood and the Rise of the

Mediating Sufi Shaykh, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC.

Burkhalter Flueckiger, J, 2006, In Ammas Healing Room: Gender and Vernacular Islam in South

India, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, MN.

Cashin, D, 1995, The Ocean of Love: Middle Bengali Sufi Literature and the Fakirs of Bengal,

Association of Oriental Studies, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden.

Chittick, WC, 1992, Notes on Ibn Arab}s Influence in the Indian Sub-Continent, Muslim

World, vol. 82, no. 34, pp. 218 41.

Christmann, A, 2008, Reclaiming Mysticism: Anti-Orientalism and the Construction of

Islamic Sufism in Postcolonial Egypt, in NS Green and M Searle-Chatterjee (eds.), Religion,

Language and Power, pp. 5782, Routledge, New York, NY.

Currim, M, & Michell, G (eds.), 2004, Dargahs: Abodes of the Saints, special issue of Marg, vol.

56, no. 1, pp. 104 19.

Dek, D, 2005, Maharashtra Saints and the Sufi Tradition: Eknath, Chand Bodhle and Datta

Sampradaya, Journal of Deccan Studies, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 22 47.

Digby, S, 1983, Early Pilgrimages to the Graves of Muin al-Din and other Chishti Shaikhs,

in M Israel and NK Wagle (eds), Islamic Society and Culture: Essays in Honour of Professor Aziz

Ahmad, pp. 95100, Manohar, Delhi, India.

Digby, S, 2004, Before Timur Came: Provincialization of the Delhi Sultanate through the

Fourteenth Century, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, vol. 47, no. 3,

pp. 298 356.

Eaton, RM, 1978, Sufis of Bijapur 1300 1700: Social Roles of Sufis in Medieval India, Princeton

University Press, Princeton, NJ.

, 1984, The Political and Religious Authority of the Shrine of BAbA Far}d, in BD Metcalf

(ed.), Moral Conduct and Authority: The Place of Adab in South Asian Islam, pp. 33356,

University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

, 1993, The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 12041760, University of California Press,

Berkeley, CA.

Ernst, CW, & Lawrence, BB, 2002, Sufi Martyrs of Love: The Chishti Order in South Asia and

Beyond, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, UK.

, 1992, Eternal Garden: Mysticism, History, and Politics at a South Asian Sufi Center, State

University of New York Press, Albany, NY.

, 1997, Shambhala Guide to Sufism, Shambhala, Boston, MA.

Fernandes, L, 1988, The Evolution of a Sufi Institution in Mamluk Egypt: The Khanqah, Klaus

Schwarz, Berlin, Germany.

Fitzgerald, T, 1990, Hinduism and the World Religions Fallacy, Religion, vol. 20, pp. 10118.

Frembgen, JW, 1999, Kleidung und Ausrstung islamischer Gottsucher. Ein Beitrag zur materiellen

Kultur des Derwischenwesens, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, Germany.

Geertz, C, 1971, Islam Observed: Religious Development in Morocco and Indonesia, University of

Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Gellner, E, 1969, Saints of the Atlas, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, UK.

, 1981, Muslim Society, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Golombek, L, 1969, The Timurid Shrine at GazurGah, University of Toronto Press, Toronto,

Canada.

Green, NS, & Chatterjee, M (eds), 2008, Religion, Language and Power, Routledge, New York, NY.

, 2006, Indian Sufism since the Seventeenth Century: Saints, Books and Empires in the Muslim

Deccan, Routledge, London, UK.

, 2008, Breathing in India, c.1890, Modern Asian Studies, vol. 42, 2 3.

Hanna, N, 2003, In Praise of Books: A Cultural History of Cairos Middle Class, Sixteenth to the

Eighteenth Century, Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, NY.

Hermansen, MK, & Lawrence, BB, 2000, Indo-Persian Tazkiras as Memorative Communications,

in D Gilmartin and BB Lawrence (eds.), Beyond Turk and Hindu: Rethinking Religious Identities

in Islamicate South Asia, pp. 14975, University of Florida Press, Gainsville, FL.

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

1060 Nile Green

, 1988, Interdisciplinary Approaches to Islamic Biographical Materials, Religion, vol. 18,

no. 4, pp. 163 82.

Horten, M, 19271928, Indishe Strmungen in Der Islamischen Mystic, vol. 2, O. Harrassowitz,

Heidelberg/Leipzig, Germany.

Huda, Q (ed.), 2007, QawwAl}: Performance and Politics, special issue of The Muslim World,

vol. 97, no. 4, pp. 5437.

Inden, R, 2000, Introduction: From Philological to Dialogical Texts, in R Inden, J Walters

and D Ali (eds.), Querying the Medieval: Texts and the History of Practices in South Asia, pp. 3

28, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Islam, R, 2002, Sufism in South Asia: Impact on Fourteenth Century Muslim Society, Oxford

University Press, Karachi, Pakistan.

Kugle, S, 2007, Sufis and Saints Bodies: Mysticism, Corporeality, and Sacred Power in Islam,

University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC.

Massignon, L, 1922, Essai sur les Origines du Lexique Technique de la Mystique Musulmane, Paul

Geuthner, Paris, France.

McChesney, RD, 1991, Waqf in Central Asia: Four hundred Years in the History of a Muslim Shrine,

Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Messick, B, 1993, The Caligraphic State: Textual Domination and History in a Muslim Society,

University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Metcalf, BD, 1982, Islamic Revival in British India: Deoband, 1860 1900, Princeton University

Press, Princeton, NJ.

Nizami, KA, 1961, Some Aspects of Religion and Politics in India during the Thirteenth Century. Asia

Publishing House, Bombay, India, revised edition printed as Religion and Politics in India during

the Thirteenth Century, Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2002.

, 1979, Review of Sufis of Bijapur by R.M. Eaton, Islamic Culture, vol. 53, no. 4,

pp. 257 61.

Qureshi, RB, 1986, Sufi Music of India and Pakistan, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Rinehart, R, 1999, The Portable Bullhe Shah: Biography, Categorization, and Authorship in

the Study of Punjabi Sufi Poetry, Numen, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 53 87.

Rizvi, SAA, 1978 & 1983, A History of Sufism in India, vol. 2, Munshiram Manoharlal, Delhi,

India.

, 1980, Shh Wal Allh and his Times, Marifat Publishing House, Canberra, Australia.

Robinson, FCR, 1993a, Scholarship and Mysticism in Early Eighteenth Century Awadh, in

AL Dallapiccola and SZ Lallement (eds.), Islam and the Indian Regions, Franz Steiner, Stuttgart,

Germany, pp. 37798; reprinted in FCR Robinson, The Ulama of Farangi Mahall and Islamic

Culture in South Asia, London: Hurst, 2001.

, 1993b, Technology and Religious Change: Islam and the Impact of Print, Modern Asian

Studies, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 229 51.

Saberwal, S & Varma, S, 2005, Traditions in Motion: Religion and Society in History, Oxford

University Press, Delhi, India.

Sanyal, U, 1996, Devotional Islam and Politics in British India: Ahmad Riza Khan Barelwi and his

Movement, 1870 1920, Oxford University Press, Delhi, India.

Schimmel, A, 1975, Mystical Dimensions of Islam, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel

Hill, NC.

, 1976, Pain and Grace: A Study of Two Mystical Writers of Eighteenth-Century Muslim India,

E.J. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands.

, 1994, Deciphering the Signs of God: A Phenomenological Approach to Islam, Edinburgh

University Press, Edinburgh, UK.

Seyller, J, 1997, The Inspection and Valuation of Manuscripts in the Imperial Mughal Library,

Artibus Asiae, vol. 57, nos 34, pp. 243349.

Shackle, C, 1999, Persian Poetry and QAder} Sufism in Later Mughal India: Ghan}mat KunjAh}

and his Mathnaw-yi Nayrang-i ishq, in L Lewisohn & D Morgan (ed.), The Heritage of

Sufism, Vol.3, Late Classical Persianate Sufism (15011750), pp. 43563, Oneworld, Oxford,

UK.

Sila Khan, D, 2000, Sheikh Burhan Chishti Le culte dun saint musulman chez les Rajpoutes

Shekhawat, in A Montaut (ed.), Le Rajasthan, Ses Dieux, Ses hros, Son peuple, pp. 15566,

Inalco, Paris, France.

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Making Sense of Sufism in the Indian Subcontinent 1061

, 2003, Conversions and Shifting Identities: Ramdev Pir and the Ismailis in Rajasthan, Manohar,

Delhi, India.

Smith, M, 1931, Studies in Early Mysticism in the Near and Middle East, Sheldon Press, London,

UK.

Stewart, C, & Shaw, R, 1994, Introduction: Problematizing Syncretism, in C Stewart and S

Shaw (eds.), Syncretism/Anti-Syncretism: The Politics of Religious Synthesis, pp. 126, Routledge,

London, UK.

, 2001, In Search of Equivalence: Conceiving the Muslim-Hindu Encounter through

Translation Theory, History of Religions, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 260 87.

Suvorova, A, 2000, Masnavi: A Study of Urdu Romance, Oxford University Press, Karachi,

Pakistan.

Taylor, CS, 1999, In the Vicinity of the Righteous: Ziyra and the Veneration of Muslim Saints in

Late Medieval Egypt, Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Trimingham, JS, 1971, The Sufi Orders in Islam, Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK.

Troll, CW, (ed.), 1989, Muslim Shrines in India: Their Character, History and Significance, Oxford

University Press, Delhi, India.

Umar, M, 1993, Islam in Northern India during the Eighteenth Century, Munshiram Manoharlal,

Delhi, India.

Werbner, P, 2003, Pilgrims of Love: The Anthropology of a Global Sufi Cult, Hurst, London, UK.

Werbner, P, & Basu, H, (eds.), 1998, Embodying Charisma: Modernity, Locality and the Performance

of Emotion in Sufi Cults, Routledge, London, UK.

Zaehner, RC, 1960, Hindu and Muslim Mysticism, Athlone Press, London, UK.

2008 The Author

Religion Compass 2/6 (2008): 10441061, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00110.x

Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

You might also like

- The Prophet's Pulpit: Islamic Preaching in Contemporary EgyptFrom EverandThe Prophet's Pulpit: Islamic Preaching in Contemporary EgyptRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Islam in the Modern World: Challenged by the West, Threatened by Fundamentalism, Keeping Faith with TraditionFrom EverandIslam in the Modern World: Challenged by the West, Threatened by Fundamentalism, Keeping Faith with TraditionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- Echoes from The Orient: A Broad Outline of Theosophical DoctrinesFrom EverandEchoes from The Orient: A Broad Outline of Theosophical DoctrinesNo ratings yet

- Sufism and the Way of Blame: Hidden Sources of a Sacred PsychologyFrom EverandSufism and the Way of Blame: Hidden Sources of a Sacred PsychologyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Reflections on the Social Thought of Allama M.T. Jafari: Rediscovering the Sociological Relevance of the Primordial School of Social TheoryFrom EverandReflections on the Social Thought of Allama M.T. Jafari: Rediscovering the Sociological Relevance of the Primordial School of Social TheoryNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Islamic Studies: From Orientalism to CosmopolitanismFrom EverandRethinking Islamic Studies: From Orientalism to CosmopolitanismRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Reconfiguring Islamic Tradition: Reform, Rationality, and ModernityFrom EverandReconfiguring Islamic Tradition: Reform, Rationality, and ModernityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Teaching Plato in Palestine: Philosophy in a Divided WorldFrom EverandTeaching Plato in Palestine: Philosophy in a Divided WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- What Is Islamic Esotericism?: Liana SaifDocument59 pagesWhat Is Islamic Esotericism?: Liana Saifibn_arabiNo ratings yet

- Religion as Critique: Islamic Critical Thinking from Mecca to the MarketplaceFrom EverandReligion as Critique: Islamic Critical Thinking from Mecca to the MarketplaceNo ratings yet

- Asian Religions in Practice: An IntroductionFrom EverandAsian Religions in Practice: An IntroductionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Islam: Religion, History, and CivilizationFrom EverandIslam: Religion, History, and CivilizationRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (36)

- Yorùbá Culture: A Philosophical AccountFrom EverandYorùbá Culture: A Philosophical AccountRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- The Construction of Belief: Reflections on the Thought of Mohammed ArkounFrom EverandThe Construction of Belief: Reflections on the Thought of Mohammed ArkounNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Religion: With Essays in African Philosophy of ReligionFrom EverandPhilosophy of Religion: With Essays in African Philosophy of ReligionNo ratings yet

- Sufism: A New History of Islamic MysticismFrom EverandSufism: A New History of Islamic MysticismRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Following Muhammad: Rethinking Islam in the Contemporary WorldFrom EverandFollowing Muhammad: Rethinking Islam in the Contemporary WorldRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Ismaili Myth Shared With KaballaDocument24 pagesIsmaili Myth Shared With KaballaDr.Ahmed GhareebNo ratings yet

- Muslim Scholars' Views On EducationDocument62 pagesMuslim Scholars' Views On Educationabdul qaharNo ratings yet

- The Emergence of Modern Shi'ism: Islamic Reform in Iraq and IranFrom EverandThe Emergence of Modern Shi'ism: Islamic Reform in Iraq and IranNo ratings yet

- Creating God: The birth and growth of major religionsFrom EverandCreating God: The birth and growth of major religionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- From Historical to Critical Post-Colonial Theology: The Contribution of John S. Mbiti and Jesse N. K. MugambiFrom EverandFrom Historical to Critical Post-Colonial Theology: The Contribution of John S. Mbiti and Jesse N. K. MugambiNo ratings yet

- 27 3anjumDocument18 pages27 3anjumSadique PK Mampad100% (1)

- Sacred Freedom: Western Liberalist Ideologies in the Light of IslamFrom EverandSacred Freedom: Western Liberalist Ideologies in the Light of IslamRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Muslim Philosophy and The Sciences - Alnoor Dhanani - Muslim Almanac - 1996Document19 pagesMuslim Philosophy and The Sciences - Alnoor Dhanani - Muslim Almanac - 1996Yunis IshanzadehNo ratings yet

- The Deoband Madrassah Movement: Countercultural Trends and TendenciesFrom EverandThe Deoband Madrassah Movement: Countercultural Trends and TendenciesNo ratings yet

- Society, the Sacred and Scripture in Ancient Judaism: A Sociology of KnowledgeFrom EverandSociety, the Sacred and Scripture in Ancient Judaism: A Sociology of KnowledgeNo ratings yet

- Postmodernity and Univocity: A Critical Account of Radical Orthodoxy and John Duns ScotusFrom EverandPostmodernity and Univocity: A Critical Account of Radical Orthodoxy and John Duns ScotusRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Journal of The Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & IrelandDocument29 pagesJournal of The Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Irelandankitabhitale2000No ratings yet

- Rethinking Islamic Studies ReviewDocument3 pagesRethinking Islamic Studies ReviewUwais NamaziNo ratings yet

- Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of TranslationFrom EverandReligion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of TranslationNo ratings yet

- SufsimDocument19 pagesSufsimkarayam2013No ratings yet

- Women and Redemption: A Theological HistoryFrom EverandWomen and Redemption: A Theological HistoryRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (3)

- Age of the Sages: The Axial Age in Asia and the Near EastFrom EverandAge of the Sages: The Axial Age in Asia and the Near EastRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Islamic Theology: January 2010Document14 pagesIslamic Theology: January 2010A Plus Abdul HafizNo ratings yet

- Monotheism in Ancient Israel - Mark SmithDocument17 pagesMonotheism in Ancient Israel - Mark SmithLeonardo FelicissimoNo ratings yet

- StudyofPhilosophy PDFDocument9 pagesStudyofPhilosophy PDFAMMMGMNo ratings yet

- PHYSICS AND SUFI COSMOLOGY: Creation of Universe and Life In the Light of Science and Philosophical Spirituality (The Cosmos and the Self)From EverandPHYSICS AND SUFI COSMOLOGY: Creation of Universe and Life In the Light of Science and Philosophical Spirituality (The Cosmos and the Self)No ratings yet

- Sheikh Ahmadu Bamba: Selected PoemsDocument227 pagesSheikh Ahmadu Bamba: Selected PoemsAbrvalg_1100% (8)

- Nile Green Making Sense of Sufism' in The Indian Subcontinent: A Survey of TrendsDocument18 pagesNile Green Making Sense of Sufism' in The Indian Subcontinent: A Survey of TrendsAbrvalg_1100% (1)

- Hayyatan Tayyabah - The Pure LifeDocument7 pagesHayyatan Tayyabah - The Pure LifeTASAWWUF100% (2)

- Current Studies in The Sociology of ReligionDocument346 pagesCurrent Studies in The Sociology of ReligionAbrvalg_1No ratings yet

- Religion in The Public Space Blue and Yellow Islam in SwedenDocument14 pagesReligion in The Public Space Blue and Yellow Islam in SwedenAbrvalg_1No ratings yet

- The Other Shadhilis of The WestDocument11 pagesThe Other Shadhilis of The WestAbrvalg_1No ratings yet

- (G. - William - Barnard) Exploring Unseen Worlds - William James and The Philosophy of MysticismDocument467 pages(G. - William - Barnard) Exploring Unseen Worlds - William James and The Philosophy of Mysticismplessiosaurus100% (1)

- A Dallal The Origins and Objectives of Islamic Revivalist Thought 1750 1850 PDFDocument20 pagesA Dallal The Origins and Objectives of Islamic Revivalist Thought 1750 1850 PDFAbrvalg_1No ratings yet

- Chodkiewicz - Seal of The Saints PDFDocument96 pagesChodkiewicz - Seal of The Saints PDFAbrvalg_1100% (1)

- Khalid Duran Muslim Diaspora: The Sufis in Western EuropeDocument22 pagesKhalid Duran Muslim Diaspora: The Sufis in Western EuropeAbrvalg_1No ratings yet

- CharismaDocument272 pagesCharismaAlexandra Alex100% (1)

- Islam Historical, SocialDocument453 pagesIslam Historical, SocialAmir Iqbal100% (4)

- Katz Steven T Ed Mysticism and Sacred Scripture 271p PDFDocument271 pagesKatz Steven T Ed Mysticism and Sacred Scripture 271p PDFAbrvalg_1100% (1)

- Tasawwuf and TablighDocument196 pagesTasawwuf and TablighAbrvalg_1No ratings yet

- Prolegomena To The Metaphysics of Islam Syed Muhammad Naquib Al Attas PDFDocument186 pagesProlegomena To The Metaphysics of Islam Syed Muhammad Naquib Al Attas PDFAbrvalg_1100% (1)

- Ron Geaves Islam Today - An Introduction 2010 PDFDocument196 pagesRon Geaves Islam Today - An Introduction 2010 PDFAbrvalg_1100% (1)

- Nicholas Heer - Papers On Islamic Philosophy Theology and MysticismDocument84 pagesNicholas Heer - Papers On Islamic Philosophy Theology and MysticismAbrvalg_1No ratings yet

- Ibn Arabis Ontology and Pantheism JIP 2 2006 PDFDocument16 pagesIbn Arabis Ontology and Pantheism JIP 2 2006 PDFAbrvalg_1No ratings yet

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr Conditions For A Meaningful Comparative Philosophy PDFDocument10 pagesSeyyed Hossein Nasr Conditions For A Meaningful Comparative Philosophy PDFAbrvalg_1No ratings yet

- Popular Sufism and Scripturalist Islam in KashmirDocument22 pagesPopular Sufism and Scripturalist Islam in KashmirAbrvalg_1No ratings yet

- Sufism and Revivalism in South AsiaDocument18 pagesSufism and Revivalism in South AsiaAbrvalg_1No ratings yet

- Theoretical Gnosis and Doctrinal SufismDocument35 pagesTheoretical Gnosis and Doctrinal Sufismruilov100% (5)

- Mandawille SolidaritiesDocument18 pagesMandawille SolidaritiesAbrvalg_1No ratings yet

- 1223545424549Document22 pages1223545424549Abrvalg_1No ratings yet

- Islamic StudiesDocument197 pagesIslamic StudiesAbrvalg_1100% (1)

- 1Document36 pages1Abrvalg_1No ratings yet

- Shah Waliullah BiographDocument34 pagesShah Waliullah BiographAbrvalg_1No ratings yet

- En Cours 2018 Lglor2613Document2 pagesEn Cours 2018 Lglor2613Ironclad773No ratings yet

- Intro To Poetry 1Document51 pagesIntro To Poetry 1Rhonel Galutera100% (1)

- Answer Key: 1. Know About The ComputerDocument37 pagesAnswer Key: 1. Know About The ComputerPrashant singhNo ratings yet

- How To Write US College Admissions Essay: PerfectDocument9 pagesHow To Write US College Admissions Essay: PerfectNazmoon NaharNo ratings yet

- Natural Language Processing (NLP) With Python - TutorialDocument72 pagesNatural Language Processing (NLP) With Python - TutorialNuttaphon CharuvajanaNo ratings yet

- Gino - Extrinsic Factors That Affect ReadingDocument9 pagesGino - Extrinsic Factors That Affect ReadingRhezan Bert DialinoNo ratings yet

- Describing Tables: Practise Exercise OneDocument3 pagesDescribing Tables: Practise Exercise OneAbdulazizNo ratings yet

- Guide Engineering Optimization L TEX Style Guide For Authors (Style 2 + Chicago Author-Date Reference Style)Document17 pagesGuide Engineering Optimization L TEX Style Guide For Authors (Style 2 + Chicago Author-Date Reference Style)skyline1122No ratings yet

- Tu FuDocument2 pagesTu FuRyan Bustillo85% (13)

- Where Does NBDP Fit in GMDSS and How To Use ItDocument14 pagesWhere Does NBDP Fit in GMDSS and How To Use ItKunal SinghNo ratings yet

- Getting Started With Nokia's Carbide - Vs 2.0 Development ToolsDocument19 pagesGetting Started With Nokia's Carbide - Vs 2.0 Development ToolsPraveen KumarNo ratings yet

- Lesson: Co-Relation With Other SubjectsDocument1 pageLesson: Co-Relation With Other SubjectsSUSANTA LAHANo ratings yet

- IPC in LinuxDocument4 pagesIPC in LinuxBarry AnEngineerNo ratings yet

- Victorian NovelDocument1 pageVictorian NovelMaria vittoria SodaNo ratings yet

- 21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The World Quarter 1 Philippine Literary HistoryDocument10 pages21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The World Quarter 1 Philippine Literary HistoryEmelyn AbillarNo ratings yet

- Begging The QuestionDocument17 pagesBegging The QuestionNicole ChuaNo ratings yet

- A STUDY OF SPEECH ACTS PRODUCED BY THE MAIN CHARACTER IN DORAEMON COMIC THE 1 ST VOLUME THESIS BY IIS MARDIANTIDocument5 pagesA STUDY OF SPEECH ACTS PRODUCED BY THE MAIN CHARACTER IN DORAEMON COMIC THE 1 ST VOLUME THESIS BY IIS MARDIANTICinderlla NguyenNo ratings yet

- Binary Opposition As The Manifestation of The Spirit of Meiji in Natsume Sōseki's KokoroDocument13 pagesBinary Opposition As The Manifestation of The Spirit of Meiji in Natsume Sōseki's KokoroTanmay BhattNo ratings yet

- Michelle EulloqueDocument2 pagesMichelle EulloqueMichelle Agos EulloqueNo ratings yet

- SSG 2Document8 pagesSSG 2Ho Hoang Giang Tho (K17 CT)No ratings yet

- Collins Get Ready For IELTS Student's BookDocument2 pagesCollins Get Ready For IELTS Student's BookBé SâuNo ratings yet

- Hadoop Final DocmentDocument79 pagesHadoop Final DocmentNaufil Ajju100% (1)

- Cavite MutinyDocument12 pagesCavite MutinyKevin BustalinioNo ratings yet

- RDF Schema - Syntax and Intuition: Werner NuttDocument52 pagesRDF Schema - Syntax and Intuition: Werner NuttAsHankSiNghNo ratings yet

- Joblana Test (JL Test) English Section Sample PaperDocument4 pagesJoblana Test (JL Test) English Section Sample PaperLots infotechNo ratings yet

- My Sore Body Immediately Felt Refreshed.Document7 pagesMy Sore Body Immediately Felt Refreshed.vny276gbsbNo ratings yet

- Cover Letter For Community Mobilization OfficerDocument2 pagesCover Letter For Community Mobilization OfficerAftab Ahmad Mohal83% (24)

- Drum LessonDocument19 pagesDrum LessonClariza InmenzoNo ratings yet

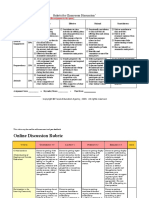

- Discussion Rubric ExamplesDocument6 pagesDiscussion Rubric ExamplesDilausan B MolukNo ratings yet

- 5th-Sunday-of-Lent (2) .2Document1 page5th-Sunday-of-Lent (2) .2Emmanuel ToretaNo ratings yet