Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vidad v. RTC of Negros Oriental

Uploaded by

mjfernandez15Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vidad v. RTC of Negros Oriental

Uploaded by

mjfernandez15Copyright:

Available Formats

Vidad v. RTC of Negros Oriental, Br.

42

October 18, 1993 | Vitug, J. | Special Civil Actions of Certiorari, Prohibition and

Mandamus | Primary Jurisdiction or Preliminary Resort

SUMMARY: A Group of public school teachers held a strike. The RD issued a

return to work order, with a warning of administrative charges for failure to comply.

The order went unheeded, hence, the teachers were charged administratively. They

filed a complaint for injunction, prohibition and damages before the RTC, which

granted a TRO, prohibiting the DECS Officials from continuing with the

administrative investigation. Defendants filed an MD, while the Plaintiffs moved to

declare defendants in default. Both motions were denied. SC ruled that the lower

court erred in issuing the TROs, citing the doctrine of primary jurisdiction, and

ordered that it suspend further proceedings until final determination on the

administrative proceedings have been made.

DOCTRINE: The doctrine of primary jurisdiction does not warrant a court to

arrogate unto itself the authority to resolve a controversy the jurisdiction over which

is initially lodged with an administrative body of special competence.

FACTS:

1. A group of public school teachers in Negros Oriental held a mass action from

Sept 19-21, 1990, to demand the release of their salaries by the Department of

Budget, as well as to assail the alleged corruption in DECS. RD Teofilo Gomez

issued a return-to-work order, with a warning that those who fail to do so within

24 hrs would be facing administrative charges, which went unheeded. As such,

admin complaints were filed, and the teacher were given 5 days from receipt of

the complaints within which to submit their answers and supporting documents.

An investigation panel was constituted.

2. Said teachers filed with the RTC of Dumaguete a complaint for injunction,

prohibition and damages, with a prayer for preliminary injunction against the

DECS officials which constituted the investigation panel, which was granted by

the court. Defendants filed their Answer, followed by an MD. The school

teachers, on the other hand, moved to strike out the appearance of the OSG and to

declare the defendants in default (They contend that the defendants are being

sued solely in their private capacity, as such the SolGen may not represent them).

Both motions were denied. From said denial, both parties filed the respective

petitions, which were consolidated, along with 4 other cases raising like issues.

3. Public school teachers: Defendants, illegally withheld their salaries, wrongfully

filed administrative charges against them, unjustifiably refused to inform them of

the nature and cause of accusation upon which the charges were initiated,

inexcusably violated elemental due process, and erroneously applied the law.

They also pray for actual and moral damages, plus attorneys fees, as well as for

an order restraining the defendants from further proceeding with the

administrative investigations.

ISSUE/S:

1.

2.

WoN the OSG may properly represent the defendants in the RTC cases

WoN the RTC should have dismissed outright the cases

HELD/RULING: DISMISSED.

RATIO:

1. The plaintiffs contention that the defendants are being sued only in their private

capacity is not borne by their allegations and prayers. In fact, the root of the cases

filed deal with the performance of official functions by the DECS Officials. WoN

such were proper or improper, or WoN they acted in good faith or bad faith,

cannot yet be determined, pending a full hearing that would afford all parties an

opportunity to ventilate their respective contentions. As such, it must be

presumed that official duties have been regularly performed.

2. The SolGen did not act improperly in deciding to represent the DECS Officials in

the above cases. PD 487 and the Administrative Code of 1987 provide that the

OSG shall represent the Government in the SC and the CA in all criminal

proceedings; represent the Government and its officers in the SC, the CA, and all

other courts or tribunals in all civil actions and special proceedings in which the

Government or any officer thereof in his official capacity is a party.

3. The various complaints filed by the public school teachers allege bad faith on the

part of the DECS officials. Assuming that plaintiffs are able to establish their

allegations of bad faith, a judgment for damages can be warranted. In such a case,

the public officials may not be said to have acted within the scope of their official

authority; thus, they are no longer protected by the mantle of immunity for

official actions, and may be held liable for damages in their personal capacities.

4. Nonetheless, it was inopportune for the lower court to issue restraining orders.

The authority of the DECS RD to issue the return to work order and to initiate the

administrative charges and to constitute the investigating panel can hardly be

disputed.

5. The SC stated that the civil cases and the administrative cases were closely

interrelated. While no prejudicial question strictly arises where one is a civil case

and the other is an administrative proceeding, in the interest of good order, it

behooves the court to suspend its action on the cases before it pending the final

outcome of the administrative proceedings. The doctrine of primary jurisdiction

does not warrant a court to arrogate unto itself the authority to resolve a

controversy the jurisdiction over which is initially lodged with an administrative

body of special competence.

Note: The Court stated in this case that the civil cases against the DECS Officials

prescinded from the administrative actions taken, or yet to be taken, against the

public school teachers. Since both matters are interlinked, even though the SC itself

pronounced that there is no prejudicial question, it resolved to suspend the case until

the final disposition of the administrative case.

You might also like

- Reyes Vs YsipDocument1 pageReyes Vs YsipKim Lorenzo CalatravaNo ratings yet

- G.R. NO. 191567, March 20, 2013Document2 pagesG.R. NO. 191567, March 20, 2013Lenneo SorianoNo ratings yet

- Mayor v. IACDocument3 pagesMayor v. IACNorberto Sarigumba IIINo ratings yet

- Comilang v. BelenDocument16 pagesComilang v. BelenRogelio BataclanNo ratings yet

- Petition For AdoptionDocument4 pagesPetition For AdoptionANGIE BERNALNo ratings yet

- Judge's erratic behavior and incompetence investigatedDocument6 pagesJudge's erratic behavior and incompetence investigatedAnne EliasNo ratings yet

- Oposa vs. FactoranDocument1 pageOposa vs. FactoranCarlota Nicolas VillaromanNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 193494Document4 pagesG.R. No. 193494Aubrey CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Trans InternationalDocument2 pagesTrans InternationalErika PinedaNo ratings yet

- Barba vs. Liceo de Cagayan UniversityDocument28 pagesBarba vs. Liceo de Cagayan UniversityCamille Yasmeen SamsonNo ratings yet

- Director of Lands Vs CA & B.A GonzalezDocument2 pagesDirector of Lands Vs CA & B.A GonzalezClay Delgado100% (1)

- CIR ruling on property disputeDocument1 pageCIR ruling on property disputeJD DXNo ratings yet

- Lee Hong Kok V David 48 SCRA 372 Facts:: Imperium, Dominium, Jura RegaliaDocument62 pagesLee Hong Kok V David 48 SCRA 372 Facts:: Imperium, Dominium, Jura RegaliaAlayka A AnuddinNo ratings yet

- Preferred Home Specialties Inc. vs. Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesPreferred Home Specialties Inc. vs. Court of AppealsKaye Mendoza0% (1)

- 14-1 Diaz-Duarte V Spouses OngDocument3 pages14-1 Diaz-Duarte V Spouses OngAngeli MaturanNo ratings yet

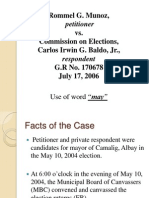

- Munoz Vs Comelec FinalDocument14 pagesMunoz Vs Comelec Finallucylu888100% (1)

- GR No. 223595 Case DigestDocument2 pagesGR No. 223595 Case DigestAthy CloyanNo ratings yet

- Atty found liable for discourtesyDocument2 pagesAtty found liable for discourtesyZelayne Genova MorpeNo ratings yet

- Laganapan Vs Mayor AsedilloDocument1 pageLaganapan Vs Mayor Asedillomamp05No ratings yet

- 3 Cosmos Foundry Shop Workers Union vs. Lo Bu, 63 SCRA 321Document13 pages3 Cosmos Foundry Shop Workers Union vs. Lo Bu, 63 SCRA 321Chiang Kai-shekNo ratings yet

- Case Digests - Land Titles and Deeds (W6)Document4 pagesCase Digests - Land Titles and Deeds (W6)Bryan Jayson BarcenaNo ratings yet

- Naguit & Malabanan PrinciplesDocument2 pagesNaguit & Malabanan Principleskath100% (3)

- Tormis v. ParedesDocument2 pagesTormis v. Paredesaudreydql5No ratings yet

- Spouses David Bergonia and Luzviminda Castillo, Petitioners, vs. Court of Appeals (4th Division) and Amado Bravo, Jr.Document3 pagesSpouses David Bergonia and Luzviminda Castillo, Petitioners, vs. Court of Appeals (4th Division) and Amado Bravo, Jr.albemartNo ratings yet

- Sps. Rebamonte v. Sps. LuceroDocument4 pagesSps. Rebamonte v. Sps. LuceroTricia Montoya100% (1)

- 14 City Treasurer of Muntinlupa Vs Manila Electric CompanyDocument1 page14 City Treasurer of Muntinlupa Vs Manila Electric CompanyLara CacalNo ratings yet

- Bagong Kapisanan Vs DolotDocument15 pagesBagong Kapisanan Vs DolotNeil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Sample Petition For Bar ExamDocument3 pagesSample Petition For Bar ExamCatNo ratings yet

- Public Interest Center v. RoxasDocument2 pagesPublic Interest Center v. RoxasChristina AureNo ratings yet

- Besaga V Sps. Acosta GR No. 194061Document2 pagesBesaga V Sps. Acosta GR No. 194061Adfat Pandan100% (2)

- 061 Padilla Rumbaua V Rumbaua PDFDocument3 pages061 Padilla Rumbaua V Rumbaua PDFJul A.No ratings yet

- HEIRS OF TABIA v. CADocument2 pagesHEIRS OF TABIA v. CACeedee RagayNo ratings yet

- Reyes V Pearlbank SecuritiesDocument2 pagesReyes V Pearlbank SecuritiesAnonymous fnlSh4KHIgNo ratings yet

- SEC v PICOP: Administrative construction fees must comply with due processDocument7 pagesSEC v PICOP: Administrative construction fees must comply with due processTristan HaoNo ratings yet

- SRA vs. Encarnacion TormonDocument4 pagesSRA vs. Encarnacion TormonTootsie GuzmaNo ratings yet

- (Barcena) Sunshine Transportation Vs NLRCDocument2 pages(Barcena) Sunshine Transportation Vs NLRCBryan Jayson Barcena100% (1)

- Cases Before Judge BalumaDocument1 pageCases Before Judge BalumaCharlie BartolomeNo ratings yet

- Mu Kappa Phi Sorority Members ListDocument7 pagesMu Kappa Phi Sorority Members ListTheGood GuyNo ratings yet

- Mohammad vs. Belgado-SaquetonDocument2 pagesMohammad vs. Belgado-SaquetonLouisa Marie QuintosNo ratings yet

- Castro Vs SecretaryDocument2 pagesCastro Vs SecretaryLemuel Angelo M. EleccionNo ratings yet

- Group 10 Assigned Villagonzalo Case 94 Andamo vs Larida JrDocument1 pageGroup 10 Assigned Villagonzalo Case 94 Andamo vs Larida JrMaddison YuNo ratings yet

- RAMOS vs. BAROTDocument1 pageRAMOS vs. BAROTJulioNo ratings yet

- 355 People v. VerzolaDocument3 pages355 People v. VerzolaSophiaFrancescaEspinosaNo ratings yet

- V ViDocument2 pagesV ViJovz BumohyaNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Versus Heirs of Sps. SanchezDocument9 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Versus Heirs of Sps. SanchezSharmen Dizon Gallenero100% (1)

- COA authority to disallow improper disbursementsDocument2 pagesCOA authority to disallow improper disbursementsNElle SAn FullNo ratings yet

- 2018 Civil Law Review 1 CasesDocument2 pages2018 Civil Law Review 1 CasesCarla VirtucioNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules Against Notary for Improper Affidavit NotarizationDocument6 pagesSupreme Court Rules Against Notary for Improper Affidavit NotarizationNikki Tricia Reyes SantosNo ratings yet

- All Jrdoss No Crsrxs or Court Op: (La Ïp Studr2Vt PractjcrjDocument16 pagesAll Jrdoss No Crsrxs or Court Op: (La Ïp Studr2Vt PractjcrjJan Erik Manigque100% (1)

- MahinayDocument2 pagesMahinayGeorlan IbisateNo ratings yet

- JOSEPHINE WEE, Petitioner v. FELICIDAD MARDO, RespondentDocument2 pagesJOSEPHINE WEE, Petitioner v. FELICIDAD MARDO, RespondentPepper PottsNo ratings yet

- FIRST AQUA SUGAR TRADERS Vs BPIDocument1 pageFIRST AQUA SUGAR TRADERS Vs BPIArlene DurbanNo ratings yet

- Shimizu V MagsalinDocument2 pagesShimizu V MagsalinManila LoststudentNo ratings yet

- International School Vs QuisumbingDocument2 pagesInternational School Vs QuisumbingMariam PetillaNo ratings yet

- People Vs Tio Won ChuaDocument1 pagePeople Vs Tio Won ChuaAshley CandiceNo ratings yet

- 07 Government Vs Cabangis G.R. No. L 28379 Mar. 27 1929Document4 pages07 Government Vs Cabangis G.R. No. L 28379 Mar. 27 1929Awe SomontinaNo ratings yet

- Application of procedural rules in administrative proceedingsDocument2 pagesApplication of procedural rules in administrative proceedingsJp tan brito100% (1)

- Vidad v. RTC Negros Oriental Branch 42, 1993 PDFDocument2 pagesVidad v. RTC Negros Oriental Branch 42, 1993 PDFLawiswisNo ratings yet

- Vidad V RTCDocument3 pagesVidad V RTCEva TrinidadNo ratings yet

- #6 - KHRISTINE REA M. REGINO vs. PANGASINAN COLLEGES OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYDocument5 pages#6 - KHRISTINE REA M. REGINO vs. PANGASINAN COLLEGES OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYYzzabel Ü Danganan100% (1)

- J. Fernandez: Won The Placing of The Iba Property in Maria'S Name Constituted Donation Inter Vivos - Not ReallyDocument2 pagesJ. Fernandez: Won The Placing of The Iba Property in Maria'S Name Constituted Donation Inter Vivos - Not Reallymjfernandez15No ratings yet

- Dauan V Secretary of Agriculture and Natural ResourcesDocument1 pageDauan V Secretary of Agriculture and Natural Resourcesmjfernandez15No ratings yet

- Public Hearing Committee of The Llda V SM Prime Holdings IncDocument1 pagePublic Hearing Committee of The Llda V SM Prime Holdings Incmjfernandez15No ratings yet

- White V RoughtonDocument1 pageWhite V Roughtonmjfernandez15No ratings yet

- Pascual V Provincial BoardDocument1 pagePascual V Provincial Boardmjfernandez15No ratings yet

- Japanese War Notes Claimants v. SecDocument1 pageJapanese War Notes Claimants v. Secmjfernandez15No ratings yet

- Autencio V ManaraDocument1 pageAutencio V Manaramjfernandez15No ratings yet

- Aboitiz Shipping Corporation V PepitoDocument1 pageAboitiz Shipping Corporation V Pepitomjfernandez15No ratings yet

- G.R. No. 146980, TAGANAS v. EMUSLANDocument2 pagesG.R. No. 146980, TAGANAS v. EMUSLANDesai Sarvida100% (1)

- Difference between civil and criminal cases explainedDocument2 pagesDifference between civil and criminal cases explainedNikkaDoriaNo ratings yet

- Evans v. Maples Et Al - Document No. 3Document5 pagesEvans v. Maples Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Consti2 - Final Course Outline - Docx2018.docx With AssigmentsDocument15 pagesConsti2 - Final Course Outline - Docx2018.docx With AssigmentsMartin FontanillaNo ratings yet

- Bangayan, Jr. v. Bangayan (GR No. 172777 & 172792)Document8 pagesBangayan, Jr. v. Bangayan (GR No. 172777 & 172792)Sherlyn SabarNo ratings yet

- 2007 S C M R 1773Document2 pages2007 S C M R 1773Movies WorldNo ratings yet

- Tanjanco C. CA DigestDocument2 pagesTanjanco C. CA DigestPia Y.No ratings yet

- Reyes V BelisarioDocument16 pagesReyes V BelisarioIs Mai RaNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction of Supreme CourtDocument11 pagesJurisdiction of Supreme CourtJasdeep KourNo ratings yet

- USA V Basim Sabri Sentencing Stipulations 2Document9 pagesUSA V Basim Sabri Sentencing Stipulations 2ghostgripNo ratings yet

- NATIONAL POWER CORPORATION vs. JUDGE JOCSON DIGESTDocument2 pagesNATIONAL POWER CORPORATION vs. JUDGE JOCSON DIGESTClavel Tuason100% (1)

- Cases Civil RevDocument206 pagesCases Civil RevMa LaneyNo ratings yet

- Cases For Crim Art 4Document48 pagesCases For Crim Art 4Valerie San MiguelNo ratings yet

- Arnesh Kumar vs. State of BiharDocument16 pagesArnesh Kumar vs. State of BiharDEVADHARSHINI SELVARAJNo ratings yet

- Spec Pro Case #1 To 10Document39 pagesSpec Pro Case #1 To 10Claudine ArrabisNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-188551 People vs. EscamillaDocument9 pagesG.R. No. L-188551 People vs. EscamillaMichelle Montenegro - Araujo0% (1)

- Supreme Court upholds transfer of public officialDocument4 pagesSupreme Court upholds transfer of public officialEumir SongcuyaNo ratings yet

- We Express No Opinion As To Subsection (F) of OCGA 51-13-1, Which Provides For Periodic Payment of Future Damages Awards of $350,000 or More in Medical Malpractice ActionsDocument29 pagesWe Express No Opinion As To Subsection (F) of OCGA 51-13-1, Which Provides For Periodic Payment of Future Damages Awards of $350,000 or More in Medical Malpractice ActionsTheBusinessInsiderNo ratings yet

- Francisco S. Reyes Law Office For Petitioners. Antonio C. de Guzman For Private RespondentsDocument23 pagesFrancisco S. Reyes Law Office For Petitioners. Antonio C. de Guzman For Private RespondentsGeanelleRicanorEsperonNo ratings yet

- SAQUILABON - KBL - Pang Et v. Dao-AsDocument2 pagesSAQUILABON - KBL - Pang Et v. Dao-AsBarrrMaidenNo ratings yet

- DEPARTMENTAL MCQ EXAMS IN REMEDIAL LAW II-RianoDocument5 pagesDEPARTMENTAL MCQ EXAMS IN REMEDIAL LAW II-RianoTricia Lacuesta100% (1)

- Makati City Appeals Taguig City Court Ruling on Fort PropertyDocument37 pagesMakati City Appeals Taguig City Court Ruling on Fort PropertyLady AltaraNo ratings yet

- Ramesh RespondentDocument13 pagesRamesh RespondentAnantHimanshuEkkaNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 6 Crossword PuzzleDocument1 pageTutorial 6 Crossword PuzzlePiriyanka RaviNo ratings yet

- De Castro V de Castro GR 160172 February 13, 2008Document5 pagesDe Castro V de Castro GR 160172 February 13, 2008Iris Jianne MataNo ratings yet

- Habeas Data 2 MERALCO, Et Al Vs LIMDocument2 pagesHabeas Data 2 MERALCO, Et Al Vs LIMJoanna Grace LappayNo ratings yet

- Kittrich v. Ralph Friedland & Bros.Document5 pagesKittrich v. Ralph Friedland & Bros.PriorSmartNo ratings yet

- 21.people v. Rodriguez, 135 Phil. 485Document11 pages21.people v. Rodriguez, 135 Phil. 485NEWBIENo ratings yet

- Administrative LawDocument5 pagesAdministrative LawDandolph TanNo ratings yet

- COMELEC Overstepped Authority in Ruling on Villarosa Nickname CaseDocument1 pageCOMELEC Overstepped Authority in Ruling on Villarosa Nickname CaseArahbellsNo ratings yet