Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Antibiotics Dutch Example

Uploaded by

rj99masterCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Antibiotics Dutch Example

Uploaded by

rj99masterCopyright:

Available Formats

BMJ 2016;354:i4192 doi: 10.1136/bmj.

i4192 (Published 3 August 2016)

Page 1 of 3

Feature

FEATURE

ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE

Saving antibiotics for when they are really needed: the

Dutch example

Doctors have responded well to the call to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions. But what

about farming? The Dutch have shown that antibiotic use can be slashed in agriculture too. So why

isnt everybody doing it? Tony Sheldon reports

Tony Sheldon journalist

Netherlands

Dutch healthcare uses the fewest antibiotics in the world, is

the bold and justifiable claim of the Dutch Health Council, the

governments independent scientific advisers. The country has

had low use for decades.1 Yet in veterinary medicine the

Netherlands, the worlds second largest exporter of agri-food

products (after the United States), was, until a few years ago,

among the highest users. This mismatch sparked action that saw

the country cut antibiotic use in farm animals by nearly 60%

from 2007 to 2015.2 3

Today the Netherlands has one of the lowest levels of

antimicrobial resistance in the world, and it believes the only

way to keep resistance levels down is for health and agricultural

sectors everywhere to work together in what it calls a One

Health approach.

If we want to control a problem in healthcare we need to act

everywhere where antibiotics are used. Because of the

continuous evolution of resistance, any reservoir could be a

source of resistant organisms to humans, says Dik Mevius,

head of the National Reference Laboratory on Antimicrobial

Resistance in Animals at the Central Veterinary Institute at

Wageningen University.

In June, after pushing the issue for six months while holding

the rotating EU presidency, the Netherlands convinced the 28

countries of the EU to commit to launching One Health national

antimicrobial resistance action plans by mid-2017.4

Edith Schippers, Dutch health minister, said that even though

countries have different situations and are at different stages in

developing national plans to tackle antimicrobial resistance,

differences between member states cannot be a reason to hinder

progress and avoid taking necessary action.

The new action plans are supposed to include measures to avoid

routine preventive use of antibiotics in agriculture and restrict

animal use of antibiotics that are of critical importance to human

health, such as carbapenems.

They should also include measureable goals adapted to fit each

countrys circumstances. A European One Health network will,

in turn, support the national plans and allow countries to

exchange information on their progress.

Antibiotics are used in huge quantities in farming, and entire

herds are often treated when a single animal falls sick or to

prevent a herd catching a disease. The EU banned the use of

antibiotics to promote animal growth in 2006 and is also now

talking about introducing a ban on preventive use of antibiotics.

Some EU countries are already clamping down as much as the

Netherlands (Denmark, Sweden), and others are taking some

additional measures (Germany, UK). But so far there has been

little transmission of resistant organisms from animals to humans

(apart from people working in close contact with animals), and

many countries, particularly those grappling with high levels

of resistance in humans, such as meticillin resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), do not see reducing use in

agriculture as a priority.

How did the Dutch do it?

Use of antibiotics by the intensive poultry, pig, and cattle farms

in the Netherlands more than doubled between 1990 and 2007.

By 2010 the country topped a European league table of the use

of antibacterial agents per weight of slaughtered animal.5

Systematic preventive use of antibiotics was simply cheaper

than stringent hygiene and infection control measures. MRSA,

endemic in the pig population, spread to farmers and vets;

resistant bacteria producing extended spectrum lactamase

(ESBL), endemic in poultry, were linked to a human death.6

There was momentum for change. This was unacceptable, in

a country with 17 million people in a small area with the

production of 450 million broiler chickens a year, who were at

that time all shedding ESBLand in a country where healthcare

was so well controlled, says Mevius.

tonysheldon5@cs.com

For personal use only: See rights and reprints http://www.bmj.com/permissions

Subscribe: http://www.bmj.com/subscribe

BMJ 2016;354:i4192 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4192 (Published 3 August 2016)

Page 2 of 3

FEATURE

As a result the Dutch Veterinary Medicines Authority was

launched, a trusted public-private partnership of food producers,

vets, and government. Within two years it had data on antibiotic

use from 40 000 farms. Mevius says: We knew which farms

used two or three times as much as others. We also knew the

vets who were prescribing more, and we were then able to start

benchmarking. We created an awareness.

At the same time parliament rapidly agreed an ambitious, if

unscientific, target of 50% reduction. A massive 58.1% in six

years followed. Today, patterns of use still vary, and a further

30% fall is still thought possible.

Mevius was surprised: We thought that in a country which has

very industrialised animal production it would be difficult to

change habits. It was in fact very easy. This shows there was

a huge overuse of antibiotics in livestock.

And crucial to the success was that it was carried out privately

by all the parties involved in animal production while the

government just imposed the targets. It was a top-down

decision to do something and a bottom-up implementation that

was the success, says Mevius.

Different medical culture

The story is different in humans. Dutch doctors dont

overprescribe antibiotics and Dutch patients dont demand them.

Studies over decades have consistently shown the Netherlands

to be among the European leaders for prudent antimicrobial use

in human health.1 Public health experts estimate 15% of the

population are prescribed antibiotics by their primary care doctor

in any one year, half or a third of the proportion in southern

European countries. The latest 2013 figures show the

Netherlands with 11 daily doses of antibiotics per 1000

population, half of the UKs rates.7 Equally, rates of MRSA

infection are among the lowest, at about 0.5% among the general

population.

In the Netherlands antibiotics must be supplied on prescription,

with primary care, which has a strong gatekeeper function in

Dutch healthcare, accounting for 80%. A culture of cautious

prescribing has been built up over decades through general

practitioners acceptance of strict professional guidance.

Indications for use, type, and dosage are issued by the College

of General Practitioners (NHG). Recent statistics show use is

continuing to decline, with a 6% fall recorded between 2011

and 2014 in daily doses of antibiotics dispensed by pharmacies.8

Jaap van Dissel, director of the Centre for Infectious Disease

Control at the National Institute for Public Health and the

Environment, says: GPs are convinced that many indications

should not be treated with an antibiotic, even though they are

in other countries. He cites the example of acute otitis media

in children.

We know from studies that the positive benefits of antibiotics

are limited. The infection causes a couple of hours pain, which

could be treated by paracetamol,9 he says.

Roger Damoiseaux, professor of general practice at Utrecht

University Medical Centre, helped draw up the NHG guidelines

advising against using antibiotics in children aged over 2 years

for common problems, including tonsillitis and sinusitis. He

has seen rates of antibiotic use fall for these conditions since

1990. Younger GPs, in particular, prescribe less. The guidelines

are really working. Training, since [the guidelines] came out,

has played a major part in bringing down the rates of

unnecessary prescribing.

Yet the Netherlands continues to push for a further 50%

reduction in both incorrect prescribing and avoidable healthcare

For personal use only: See rights and reprints http://www.bmj.com/permissions

related infection from 2015 to 2020. It has recently launched a

publicity campaign to increase national awareness of the need

to avoid using antibiotics whenever possible.

Can other countries follow the Dutch

example?

The Dutch are fortunate. Their country and population are

relatively small, perhaps making it easier to bring all the

necessary players on board to cooperate in a One Health

approach. Dutch hospital architecture allows for the option of

single rooms, so patients can be easily isolated to control

outbreaks of infection such as Clostridium difficile. Dutch

farmers all have computerised systems, unlike in many countries,

which allow monitoring and comparisons of antibiotic use.

The Dutch also consciously decided to make antimicrobial

resistance a priority sooner than most countries. Decades of

work on hospital infection through the Prevention Working

Group and promoting prudent antimicrobial use through the

Working Party on Antibiotic Policy (http://www.swab.nl/

english) means that these issues are foremost in the minds of

the professionals, says van Dissel.

In some countries the agricultural sector may be a reluctant to

act if it is more cost effective to use preventive antibiotics at

moments of risk, such as when weaning piglets, than to take

measures to improve hygiene. Meanwhile Meviuss plea to act

everywhere is easier to ignore if multidrug resistant Klebsiella

or MRSA is already endemic in hospitals.

Although actions have to fit the cultural context of each

country, Van Dissel fears that in some it is a less important

topic than others. We are now at a point where we need to

convince policy makers, including on a European level, that

these are important issues. It is a matter of the priorities of the

politicians.

In the UK, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural

Affairs is leading a five year antimicrobial resistance strategy

in animals for 2013-18.10 This encourages good farm

management, biosecurity, and animal husbandry to reduce the

risk of disease and minimise the need for antibiotic use in

animals. In May, a review of antimicrobial resistance by

economist Jim ONeill commissioned by the UK government

and the Wellcome Trust, highlighted reducing the extensive

and unnecessary use of antibiotics in agriculture as one of four

main interventions.11

Whether the EU health ministers agreement under the Dutch

presidency will give the One Health approach a further boost

in the post-Brexit UK remains to be seen. But it has been largely

welcomed elsewhere.

Sascha Marschang, policy manager of the Brussels based

network of not-for-profit health organisations, the European

Public Health Alliance, told The BMJ that while the agreement

the Dutch achieved during their EU presidency was progress,

she feared the plans risk not being concrete enough for the

scale and urgency of the threat. Crucially, she urged that

stronger legislation is needed to remove any financial incentives

to individuals and institutions to use antimicrobials gratuitously.

Instead, across Europe, vets and farmers should rather be

incentivised to reduce prophylactic use and improve animal

welfare to reduce the need for antimicrobials.

The Dutch believe that the US and Canada are also following

their achievements with interest. Any solution would need to

be global. The ONeill report pointed out that in the US, 70%

(by weight) of antibiotics defined as medically important for

Subscribe: http://www.bmj.com/subscribe

BMJ 2016;354:i4192 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4192 (Published 3 August 2016)

Page 3 of 3

FEATURE

humans by the Food and Drug Administration, were sold for

use in animals.

Dutch health minister Schippers highlighted the importance of

international action to her EU colleagues at the June meeting.

She stressed that antibiotic resistance would be on the agenda

for the United Nations General Assembly in New York this

September. She and other Dutch representatives will be there.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on

declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; not externally peer

reviewed.

1

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, European Food Safety Authority,

European Medicines Agency. ECDC/EFSA/EMA first joint report on the integrated analysis

of the consumption of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in

bacteria from humans and food-producing animals. EFSA J 2015;13:4006doi:10.2903/j.

efsa.2015.4006.

Mevius D, Heerderik D. Reduction of antibiotic use in animals lets go Dutch.J Verbr

Lebensm 2014;9:177. doi:10.1007/s00003-014-0874-z.

For personal use only: See rights and reprints http://www.bmj.com/permissions

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Speksnijder DC, Mevius DJ, Bruschke CJ, Wagenaar JA. Reduction of veterinary

antimicrobial use in the Netherlands. The Dutch success model. Zoonoses Public Health

2015;62(Suppl 1):79-87. doi:10.1111/zph.12167. pmid:25421382.

European Council. Council conclusions on the next steps under a One Health approach

to combat antimicrobial resistance. Press release, 17 Jun 2016. www.consilium.europa.

eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/06/17-epsco-conclusions-antimicrobial-resistance.

Grave K, Torren-Edo J, Mackay D. Comparison of the sales of veterinary antibacterial

agents between 10 European countries. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65:2037-40. doi:

10.1093/jac/dkq247 pmid:20587611.

Sheldon T. Dutch doctors warn of dangers of overuse of antibiotics in farming. BMJ

2010;341:c5677. doi:10.1136/bmj.c5677.

CBS. Within Europe, antibiotics use lowest in the Netherlands. https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/

news/2016/06/within-europe-antibiotics-use-lowest-in-the-netherlands.

ZonMw. Antibiotic resistance programme. 2015. http://www.zonmw.nl/uploads/tx_

vipublicaties/Prorammatekst_Antibiotica_Resistentie.pdf).

Van Buchem FL, Dunk JH, vant Hof MA. Therapy of acute otitis media: myringotomy,

antibiotics, or neither? A double-blind study in children. Lancet 1981;318:883-7.http://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=6117681&

dopt=Abstractdoi:10.1016/S0140-6736(81)91388-X.

Department of Health. Department of Food Agriculture and Rural Affairs, UK five year

antimicrobial resistance strategy 2013 to 2018. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/

uploads/attachment_data/file/244058/20130902_UK_5_year_AMR_strategy.pdf.

Review on microbial resistance. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report

and recommendations. May 2016. http://amr-review.org/.

Published by the BMJ Publishing Group Limited. For permission to use (where not already

granted under a licence) please go to http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/

permissions

Subscribe: http://www.bmj.com/subscribe

You might also like

- A Study of AntsDocument2 pagesA Study of Antsrj99masterNo ratings yet

- Armoury of The ExoditesDocument1 pageArmoury of The Exoditesrj99masterNo ratings yet

- 5IT01 01 Que 20110110Document24 pages5IT01 01 Que 20110110rj99masterNo ratings yet

- 5IT01 01 Que 20110110Document24 pages5IT01 01 Que 20110110rj99masterNo ratings yet

- 2.2.3 Amylase PH ProcedureDocument15 pages2.2.3 Amylase PH Procedurerj99masterNo ratings yet

- Siri Guru Granth Sahib, RomanizedDocument1,432 pagesSiri Guru Granth Sahib, Romanizedrj99masterNo ratings yet

- 40k Army List Eldar1000Document2 pages40k Army List Eldar1000rj99masterNo ratings yet

- EldarDocument2 pagesEldarrj99masterNo ratings yet

- Change LogDocument2 pagesChange Logrj99masterNo ratings yet

- EldarDocument2 pagesEldarrj99masterNo ratings yet

- EldarDocument2 pagesEldarrj99masterNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS) For Pain Assessment in Intubated Patients - MDCalcDocument2 pagesBehavioral Pain Scale (BPS) For Pain Assessment in Intubated Patients - MDCalcJeane SuyantoNo ratings yet

- Very Early Signs and SymptomsDocument3 pagesVery Early Signs and SymptomsMichelle TeodoroNo ratings yet

- Urinalysis in Children and Adolescents, (2014)Document11 pagesUrinalysis in Children and Adolescents, (2014)Enrique MANo ratings yet

- Safety Culture AHRQDocument8 pagesSafety Culture AHRQangga rizkiNo ratings yet

- 2014 Final With Answers: 10000 SeriesDocument36 pages2014 Final With Answers: 10000 SeriesMareeswaranNo ratings yet

- Raynaud'S Phenomenon: Dr. Ajay Panwar Japi (May 2010)Document23 pagesRaynaud'S Phenomenon: Dr. Ajay Panwar Japi (May 2010)Ajay PanwarNo ratings yet

- Syndrome Differentiation According To The Eight Principles - TCM Basic Principles ShennongDocument5 pagesSyndrome Differentiation According To The Eight Principles - TCM Basic Principles ShennongYi-Ying LuNo ratings yet

- Recommended Procedures For Doctors and Nurse in The Management of Kawasaki DiseaseDocument34 pagesRecommended Procedures For Doctors and Nurse in The Management of Kawasaki DiseaseJOSHUA DICHOSONo ratings yet

- Chest Physiotherapy For Pneumonia in ChildrenDocument30 pagesChest Physiotherapy For Pneumonia in ChildrenristaseptiawatiningsihNo ratings yet

- 2018 HIV GuidelinesDocument125 pages2018 HIV GuidelinesAndrew KaumbaNo ratings yet

- 7 Stars Doctors Required by WHO and FKUIDocument2 pages7 Stars Doctors Required by WHO and FKUIWidya Ayu92% (12)

- Essay About Why We Need Physiology in Our LifeDocument8 pagesEssay About Why We Need Physiology in Our LifeWendelieDescartinNo ratings yet

- Different Therepeutic Category of Drugs and Its Example Drug ProductsDocument8 pagesDifferent Therepeutic Category of Drugs and Its Example Drug ProductsGermie PosionNo ratings yet

- PR Truenat WHO Endorsement 02072020Document4 pagesPR Truenat WHO Endorsement 02072020KantiNareshNo ratings yet

- Pfeiffer 5 Ppts Chapter05 - The Psychology of Injury (Student Copy)Document13 pagesPfeiffer 5 Ppts Chapter05 - The Psychology of Injury (Student Copy)api-287615830No ratings yet

- Pulmonary FibrosisDocument4 pagesPulmonary FibrosisDimpal Choudhary100% (2)

- DesenteryDocument3 pagesDesenteryAby Gift AnnNo ratings yet

- Heparin and WarfarinDocument2 pagesHeparin and WarfarinBaeyer100% (1)

- Immune Thrombocytopenia: Causes of Secondary ITPDocument3 pagesImmune Thrombocytopenia: Causes of Secondary ITPkrataiwanNo ratings yet

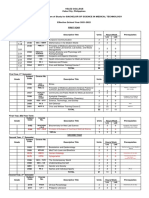

- Velez College Cebu City, Philippines: GEC - PC GEC - MMW Pmls 1Document3 pagesVelez College Cebu City, Philippines: GEC - PC GEC - MMW Pmls 1Armyl Raul CanadaNo ratings yet

- CA A Cancer J Clinicians - 2018 - Bray - Global Cancer Statistics 2018 GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and MortalityDocument31 pagesCA A Cancer J Clinicians - 2018 - Bray - Global Cancer Statistics 2018 GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and MortalityAngelia Adinda AnggonoNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 Pandamic by PriyanshDocument5 pagesCovid-19 Pandamic by PriyanshShri ram PujariNo ratings yet

- RPT - 54 - Stereotactic Radiosurgery PDFDocument50 pagesRPT - 54 - Stereotactic Radiosurgery PDFMaría José Sánchez LovellNo ratings yet

- Discharge PlanDocument1 pageDischarge PlanGail GenturalezNo ratings yet

- Community Health Nursing Vs Public Health NursingDocument1 pageCommunity Health Nursing Vs Public Health NursingAnnalisa Telles100% (2)

- Thesis SumaryDocument7 pagesThesis SumaryAnonymous hnIkb5No ratings yet

- BSC Nursing: Medical Surgical Nursing - I Unit V - Disorders of The Cardio Vascular SystemDocument36 pagesBSC Nursing: Medical Surgical Nursing - I Unit V - Disorders of The Cardio Vascular SystemPoova RagavanNo ratings yet

- Example - Pharmacist Care PlanDocument10 pagesExample - Pharmacist Care PlanHOD ODNo ratings yet

- 1cardiovascular and Pulmonary Physical TherapyDocument347 pages1cardiovascular and Pulmonary Physical TherapyLiviu CuvoiNo ratings yet

- Felix Widal TestDocument9 pagesFelix Widal TestGaluhAlvianaNo ratings yet