Professional Documents

Culture Documents

188-Knowledge, Attitude and Practice On Antenatal Care

Uploaded by

Jesselle LasernaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

188-Knowledge, Attitude and Practice On Antenatal Care

Uploaded by

Jesselle LasernaCopyright:

Available Formats

Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine 2011, Vol.

11(2): 13-21

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDE AND PRACTICE ON ANTENATAL CARE AMONG ORANG

ASLI WOMEN IN JEMPOL, NEGERI SEMBILAN

Rosliza AM 1, Muhamad JJ 1

1

Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia.

ABSTRACT

The maternal health status of Orang Asli women in Malaysia was noted to be lower as compared to other groups of

population in the country. This study aimed to determine the level of knowledge, attitude and practice on antenatal care,

which is a vital component of maternal health among the Orang Asli women in three Orang Asli villages in Jempol District,

Negeri Sembilan. All women aged between 15 to 49 years old who had at least one antenatal experience were interviewed

using a structured, pretested questionnaire. A total of 104 women were interviewed. Among them, 92.3% admitted

attending antenatal clinic during their previous pregnancies while only 48.1% came early for their first check-up. About

70% of the women had history of home delivery and 44.2% had experienced at least one high risk pregnancy before. Study

revealed that 44.2% (95% CI, 34.7 53.7%) of the women have good knowledge regarding antenatal care while 53.8% (95%

CI, 44.3 63.1%) of them noted to have positive attitude regarding antenatal care. However, result showed that the level

of knowledge regarding the importance of early antenatal care, screening test and complications of diabetes and

hypertension in pregnancy were poor. In conclusion, the rate of home delivery and late antenatal booking was still high

among the Orang Asli women and it is significantly associated with their attitude regarding antenatal care. These findings

can be used to plan a customized health intervention program aiming to improve the maternal health practices and

eventually improve the health status of the Orang Asli women.

Key words: Antenatal care, knowledge, Malaysia, Orang Asli, practice.

INTRODUCTION

Appropriate antenatal care is one of the pillars of

Safe Motherhood Initiatives, a worldwide effort

launched by the World Health Organization (WHO)

and other collaborating agencies in 1987 aimed to

reduce the number of deaths associated with

pregnancy and childbirth1. It highlights the care of

antenatal mothers as an important element in

maternal healthcare as appropriate care will lead

to successful pregnancy outcome and healthy

babies. All pregnant ladies are recommended to go

for their first antenatal check-up in the first

trimester to identify and manage any medical

complication as well as to screen them for any risk

factors that may affect the progress and outcome

of their pregnancy. According to the Perinatal Care

Manual recently edited by the Ministry of Health

Malaysia, primigravida women are advised to go for

a total of ten visits during their pregnancy and for

multigravida women, the total recommended

antenatal visit is seven sessions2.

The Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) in Malaysia has

been maintained to be below 40 per 100,000

livebirths since the 1990s3. However, there are still

groups of marginalized women with poor maternal

health status in Malaysia such as the Orang Asli

women as demonstrated elsewhere in the world

among other indigenous communities4,5. The Orang

Asli, the indigenous minority community of

Peninsular Malaysia, are considered one of the

marginalized group due to their impoverished

condition and lack of access to resources. There

were 141,230 Orang Asli population in 2008 and 50%

of them were categorized to be in hard-core

poverty group. They are usually divided into three

main groups: Senoi (54.1%), Proto-Malay (42.7%)

and Negrito (3.2%)6. Midwives and traditional

healers are important figures in the Orang Asli

traditional health system.

It was reported that the MMR among Orang Asli

women in 2002 was 480 per 100,000 livebirths,

which was more than ten times higher as compared

to the national data of 30 such deaths per 100,000

livebirths in the same year3,7. Although the health

status of Orang Asli women has improved over the

years, it is still not at par with the national

benchmark. Among the Orang Asli women in Negeri

Sembilan in 2009, the MMR was reported to be 35.7

per 100,000 livebirths which was about 30% higher

than the national rate8. The antenatal care

Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine 2011, Vol. 11(2): 13-21

coverage among Orang Asli was also reported to be

lower as compared to the national level. According

to a survey done by Lim & Chee in 1998 among

Orang Asli women in the state of Pahang, only

about 64% of them came for early antenatal check

up9. Similar situation was reported in another rural

area in Malaysia where only about 50% of pregnant

Orang Asli women came for their first antenatal

booking in the first trimester10.

Health knowledge is a vital element to enable

women to be aware of their health status and the

importance of appropriate antenatal care. At this

moment, data on maternal health status of Orang

Asli women is scarcely available. This study was

conducted to determine the level of knowledge,

attitude and practice related to antenatal care

among these underpriviledged women in selected

Orang Asli communities in Jempol District, Negeri

Sembilan which will be used as baseline data for

further planning of health intervention programme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a cross sectional survey conducted between

February and April 2011 to assess the knowledge,

attitude and practice on antenatal care among the

residents in three Orang Asli settlements in Jempol

District, Negeri Sembilan, namely Kampung Sungai

Cherbang, Kampung Sungai Sot and Kampung Sungai

Lui. Majority of the people were from the Semelai

and Temuan tribe which were classified under the

Proto-Malay subgroub of Orang Asli. There were a

total of 578 residents and 150 households in the

three villages. The nearest health facility is the

Klinik Desa Sungai Lui which is about 7 km from

Kampung Sungai Lui and 20 km from both Kampung

Sungai Sot and Kampung Sungai Cherbang. There

was no public transport service in the village and

the residents were still practicing their culture

which includes the traditional health practices.

The sample size was calculated using the formula

by Snedecor and Cochran (1989) giving a minimum

sample size of 94 at 5% level of significance and

margin of error at 10%. All women aged between 15

to 49 years old who have had at least one

pregnancy experience were invited to participate

in the study. The women who consented were

interviewed using a structured questionnaire by a

group of trained interviewers. The questionnaire

was developed in English and was translated to

Bahasa Melayu for the purpose of the interview.

Back translation of the questionnaire was

performed by independent researcher to improve

the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. To

ensure internal consistency, reliability test for the

knowledge and attitude scale were performed

giving the Cronbachs Alpha value of 0.806 and

0.812 respectively.

Pretesting of the questionnaire was conducted

among another population of Orang Asli women in

Kampung Sungai Sampo, Jempol prior to data

collection to assess the face validity of the

questionnaire.

Data on socio demography (age, education, marital

status, income and transport), pregnancy history,

knowledge, attitude and several antenatal

practices were collected. The questions on

knowledge and attitude were subdivided into

several sections such as the knowledge and attitude

on early booking, nutrition in pregnancy, follow up,

screening test and preparation for delivery. The

components of antenatal practice measured in this

study were whether they went for antenatal check

up, timing of their first antenatal check-up, the

attendance of follow up and the consumption of

iron supplement. For multiparous women, they

were assessed based on their experience and

antenatal practice of the latest pregnancy.

Information gathered from the respondents was

reconfirmed by checking their antenatal records in

the health clinic.

Data analysis was performed by using SPSS version

1911. Descriptive analysis was performed by using

frequencies, percentages, means and standard

deviations. Ethical approval to conduct the study

was obtained from the Medical Research Ethics

Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Health

Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia with the

reference

number

of

UPM/FPSK/PADS/T7MJKEtikaPer/F01(Jkk(u)SPK3811_Mac(11)08).

RESULTS

General characteristics of subjects

A total of 104 women agreed to participate in this

study. The socio demographic characteristics are

shown in Table 1. The largest number of the

respondents (46.2%) was from the age group of 20

to 29 years. A total of 84.6% were from Semelai

tribe. Quite a high proportion of the women

(42.3%) did not receive any primary or secondary

education. About 61.5% of them were housewives

while 38 (36.6%) of them worked as rubber tapper.

Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine 2011, Vol. 11(2): 13-21

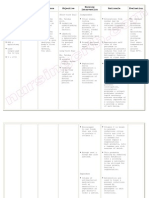

Table 1. General characteristics of the respondents (N=104)

Characteristics

Frequency

Percentage (%)

15 - 19

10

9.6

20 - 24

20

19.2

25 - 29

30

28.9

30 - 34

18

17.3

35 - 39

5.8

40 - 44

18

17.3

Above 45

1.9

Semelai

88

84.6

Temuan

12

3.9

Jahudi

11.5

Farmer

1.9

Housewife

64

61.5

Rubber tapper

38

36.6

No formal education

44

42.3

Primary School

46

44.2

Lower secondary

7.7

Upper secondary

5.8

0 - 249

26

25.0

250 - 499

70

67.3

500 - 749

3.85

750 - 1,000

3.85

Above 1,000

Motorcycle

80

76.9

Healthcare van

10

9.6

Car

12

11.6

Walking

1.9

Age group

Tribe

Occupation

Education level

Household income (RM)

Transportation to access health facility

Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine 2011, Vol. 11(2): 13-21

The household income of all the respondents

ranged between RM50 to RM1,000 where 92.3% of

them have to survive with less than RM500 for their

household per month. The mean income was RM388

(standard deviation, SD = RM178). The main

transportation used by the women to access health

facilities during their pregnancy were motorcycles

(76.9%). However, ten out of 104 women still rely

on the vehicle provided by the health clinics to go

for their antenatal check-up.

Reproductive history

Regarding history of previous pregnancies, 44.2% of

the Orang Asli women have had at least one high

risk pregnancy before. The number of the

respondents children ranged between one and

fifteen per women with 28.8% of them having more

than

five

children

and

categorized

as

grandmultipara. A total of 72 women (69.2%) had

history of home delivery. Among the Orang Asli

women interviewed, 16.4% of them had

experienced at least one episode of miscarriage.

Fourteen (13.5%) of them had history of one

stillbirth before while four (3.8%) of the Orang Asli

women had history of more than one stillbirth.

Knowledge on antenatal care

Table 2 shows the Orang Asli womens responses to

the question on knowledge regarding antenatal

care. There were 20 questions on knowledge, each

correct answer was given one mark and no mark

was given for wrong answer. In this survey, the

knowledge score of the respondents ranged

between 7 to 18 with the mean of 13.5 (SD=2.7)

and median of 14.0 (Interquartile Range, IQR=3).

The score was normally distributed. The knowledge

score was further divided to two levels which are

good knowledge and poor knowledge using the

mean knowledge score as the cutoff point. The

proportion of respondents with good knowledge

was 44.2 percent with 95% confidence interval of

34.7 to 53.7 percent. Further analysis of the

questions on knowledge revealed that majority

(94.2%) of the Orang Asli women know that

pregnant women need to go for antenatal checkup. However, only 73.1% know that the first

antenatal check-up should be done in the first

three months. About a quarter of the women didnt

know the harmful effect of smoking and alcohol

intake in pregnancy. About half of the women

didnt know the complication which may arise with

hypertension and diabetes in pregnancy. Only 80%

of the Orang Asli women know that primigravida

should deliver in hospital.

Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine 2011, Vol. 11(2): 13-21

Table 2. Knowledge on antenatal care among Orang Asli women in Jempol District (N=104)

Code

Knowledge on antenatal care

No. of subjects with

correct answer

98

Percentage (%)

KI

Do pregnant women need to go for antenatal check-up?

K2

Should first antenatal check-up be done in the first 3

months?

Does pregnant woman need vitamin supplement?

Does maternal smoking harmful to the fetus?

Should you take alcohol to provide extra energy during

pregnancy?

76

73.1

96

80

72

92.3

76.9

69.2

K6

Does pregnant woman need to come for at least five

antenatal follow up throughout her pregnancy?

80

76.9

K7

Can a pregnant woman go to the Klinik Desa for

antenatal follow-up?

100

96.2

K8

Should a pregnant woman see the doctor for antenatal

care only if she has pregnancy complication?

42

40.4

Blood screening for Hepatitis B infection

Blood screening for HIV infection

Blood screening for hemoglobin level

Blood pressure examination

Blood sugar level

Urine test for bacterial infection

Can high blood pressure affect the fetus growth?

Do diabetic women have higher risk of having big

babies?

Is ultrasound scan safe for the fetus?

Is antenatal class good to prepare expecting mothers

mentally?

52

34

82

90

72

20

58

44

50.0

32.7

78.8

86.5

69.2

19.2

55.8

42.3

88

82

84.6

78.8

Can emotional disturbance affect fetal growth?

Should women deliver in the hospital for their first

pregnancy?

54

84

51.9

80.0

K3

K4

K5

94.2

Does pregnant woman need to undergo the following test during

her antenatal check-up?

K9

K10

K11

K12

K13

K14

K15

K16

K17

K18

K19

K20

Attitude on antenatal care

The initial statements in the questionnaire

consisted of a mixture of positive and negative

statement which has been recoded to positive

statements and presented in Table 3. There were

14 statements with 5-point Likert Scale agreement

options to measure the attitude level which were

given 1 to 5 marks. For the purpose of this paper,

the response to the option for strongly agree and

agree were reported cumulatively so as the

response to strongly disagree and disagree. The

minimum possible score was 14 and the maximum

possible score was 70. Result shows that the

attitude level of the Orang Asli women ranged from

46 to 70 with the mean score of 66.2 (SD=2.3) and

median of 64.0 (IQR=12). The score was normally

distributed. The attitude score was further divided

to two levels which are good attitude and poor

attitude using the mean attitude score as the cutoff point. The proportion of respondents with good

attitude was 53.8 percent with 95% confident

interval of 44.3 to 63.1 percent. For the individual

questions, it was noted that there was a good

response to the statement on the importance of

early antenatal booking where 88.5% of the

respondents agreed to it. About 82.7% of the

respondents strongly agreed and agreed to go for

their first antenatal booking before the third month

Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine 2011, Vol. 11(2): 13-21

Table 3. Attitude towards antenatal care among the Orang Asli women in Jempol District (N=104)

Code

Statements

No. of subject with specific responses (%)

Strongly

Disagree &

Disagree

Unsure

Strongly

Agree &

Agree

A1

Early antenatal booking is good for my

pregnancy

4 (3.8)

8 (7.7)

92 (88.5)

A2

I will go for antenatal booking before the

third month of my pregnancy

10 (9.6)

8 (7.7)

86 (82.7)

A3

I believe that vitamin supplement is good

for the fetus

2 (1.9)

102 (98.1)

A4

I feel that smoking is harmful to the fetus

24 (23.0)

2 (1.9)

78 (75.1)

A5

I believe alcohol drinking will affect fetal

growth

18 (17.3)

12 (11.5)

74 (71.2)

A6

I will go for antenatal check up in the

Klinik Desa if I am pregnant

4 (3.8)

100 (96.2)

A7

Antenatal follow up is good to monitor

mothers and fetus health

6 (5.8)

6 (5.8)

92(88.4)

A8

I will allow the doctor to take my blood

for screening if I am pregnant

2 (1.9)

2 (1.9)

100 (96.2)

A9

I will allow the doctor to check my blood

pressure if I am pregnant

2 (1.9)

102 (98.1)

A10

I will check my blood sugar level if I am

pregnant

2 (1.9)

4 (3.8)

98 (94.3)

A11

I am willing to do ultrasound scan during

my pregnancy

4(3.8)

10 (9.6)

90 (86.5)

A12

I plan to deliver in the hospital if I am

pregnant

6 (5.8)

8(7.7)

90 (86.5)

A13

I will do early preparation for the delivery

if I am pregnant

104 (100.0)

A14

I am ready to face any pregnancy and

delivery complication if I am pregnant

4 (3.8)

10 (9.6)

90 (86.5)

of their pregnancy. Almost all of the respondents

(102 out of 104) agreed that vitamin supplements

are important for their pregnancy. In terms of their

attitude regarding smoking and alcohol drinking

during pregnancy, about three quarter of the

women agreed that both practices might have

harmful effect to the fetus. Majority of the women

agreed to be screened if they need to go for

antenatal check-up.

Selected antenatal practices

Several areas of antenatal practices were explored

in this survey. The women were asked on their

antenatal follow up attendance and 92.3% of the

women admitted that they did come for antenatal

visit during all their previous pregnancies. This was

confirmed by the presence of previous antenatal

follow-up cards. However, only 48.1% admitted

that they came for their antenatal checkup in the

first 3 months of their pregnancy while 54 of them

came at their fourth month or later. In general, the

Orang Asli women attended their first antenatal

check-up between their first month and seventh

months of pregnancy with the mean of 3.7 (SD=1.3

Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine 2011, Vol. 11(2): 13-21

months). About 60% of the Orang Asli women who

came late for their first antenatal check-up were

young mothers aged below than 30 years. All 104

respondents claimed that they took vitamin

supplement which was provided by the health clinic

during their last pregnancy. The average number of

antenatal visit per women was only 4.3 (SD=1.6)

visits per woman.

Relationship between knowledge, attitude and

practice

Pearson correlation test was performed to look at

the relationship between the mean knowledge

score and the mean attitude score of the

respondents. Results showed a significant positive

and moderate relationship between the knowledge

and attitude score (p=0.01 with correlation

coefficient, r=0.469). Further analysis of the

relationship between knowledge and attitude score

and selected antenatal practice (early antenatal

booking and home delivery) was performed by using

independent sample t-test. It was noted that

knowledge score was not significantly associated

with both early antenatal booking (p=0.279) and

home delivery (p=0.264). However, there were

significant relationship between the attitude score

and early antenatal booking (p=0.032) as well as

home delivery (p=0.047).

DISCUSSION

The respondents in this study has quite similar

characteristic with other Orang Asli women in

Malaysia in terms of education, occupation and

household income where majority of them did not

receive formal education, function as fulltime

housewives and live in poor households7. These

conditions pose a greater health risk to them as

many other disadvantage indigenous women

elsewhere4,12. Various studies among the Orang Asli

communities in Malaysia have also demonstrated

that poverty and household food insecurity had

resulted in malnutrition and chronic energy

deficiency among the population including women

of reproductive age group which subsequently may

lead to unfavourable pregnancy outcome13,14. In

this instance, effective poverty eradication

programme would be very important to act as the

catalyst in breaking the cycle of poverty and poor

health among the population of Orang Asli.

In this survey, it was noted that high risk pregnancy

was common among the Orang Asli women. The

proportion of grandmultipara was also high which

act as additional risk if they ever want to conceive

again. About half of the women did not know the

complications that might arise among hypertensive

and diabetic mothers. These high risk women need

specific antenatal care and recommended for

hospital delivery. However, home delivery is still a

preferred practice among the Orang Asli community

where about two third of the women reported

having experience of home delivery in their

previous pregnancies contradicting to the good

attitude demonstrated regarding hospital delivery.

Similar preference of home delivery has been

reported involving Orang Asli women which may be

due to familiarity and strong influence of

traditional health practices15. The practice of home

delivery certainly is an important aspect to improve

in maternal care as it was demonstrated by the

CEMD report that 30.5% of maternal death involved

women who delivered at home16.The rate of safe,

hospital delivery can be increased among the Orang

Asli women if proper health intervention which are

sensitive to the cultural practices and specific

needs of the women is introduced. A report by

Gabrysch et al. (2009) has proven that cultural

adaptation of birthing services has successfully

increased the number of deliveries in health

facilities by the indigenous women in rural Peru17.

The importance of knowledge and awareness

among different groups of women as factors

affecting the acceptance and utilization of health

services has been shown in other studies18,19.

Similarly, appropriate knowledge and attitude is

vital in ensuring sustainable acceptance of

antenatal services among the Orang Asli women.

This study revealed that the respondents have

inadequate knowledge regarding the importance of

coming early for their first antenatal check-up.

Their ignorance resulted in late antenatal booking

where only 48.1% of the women came for their

antenatal booking in the first trimester. This is

lower as compared to findings in another rural

settlement in Pahang state, where 63.6% of the

Orang Asli women interviewed admitted going for

their first antenatal check up in the first

trimester9. However, the result is comparable to a

review on antenatal care among indigenous group

in Australia where the proportion of women in

Australias Aboriginal population who went for their

first antenatal check up in the first trimester

ranged between 34% to 49%12.

Result showed quite a high proportion of women

who came late for their antenatal booking were

young mothers aged less than 30 years. This is an

important point to be considered in any

Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine 2011, Vol. 11(2): 13-21

intervention program planned for these women

since they will be in reproductive period for the

next 20 years or more. These vulnerable women

can easily end up with high risk pregnancy resulting

in poor maternal and fetal outcome if no proper

antenatal care is offered to them early. Therefore,

it is imperative to educate these women and her

family on appropriate maternal health practices.

In terms of access to healthcare services, the

findings of this study revealed that majority of the

women used their own transport to go for antenatal

check-up resulting in good coverage of antenatal

follow up among the women. This is probably due

to availability of proper road connecting the village

to the nearest clinic. Different findings might be

shown if the study is conducted in other remote

Orang Asli villages as about 40% of Orang Asli

villages in Peninsular Malaysia were not accessible

by land transportation7.

As an effort to reduce the high incidence of iron

deficiency anaemia among the Orang Asli

women9,13, vitamin supplements were given to

them antenatally. This study revealed that majority

of the Orang Asli women has good knowledge and

attitude regarding nutritional supplement during

pregnancy. This fact is strengthened by the high

proportion of women who

took vitamin

supplements from the clinic during their antenatal

follow-up. However, the outcome of vitamin

supplementation in terms of hemoglobin level was

not captured by this study. Future research in this

area will be beneficial in looking at the

acceptance, tolerance and impact of vitamin

supplementation among the Orang Asli women.

The findings of this study, however has its own

limitations. The Semelai, Temuan and Jahudi

subtribe of the respondents which is classified

under the Proto-malay tribe only represent 42.7%

of the Orang Asli population in Malaysia. Different

findings might be seen if the study is conducted

among the Senoi or Negrito tribe due to different

cultural practices, norms and belief. The location

of the study which is accessible by road also affect

the accessibility to healthcare hence affecting the

health practices of the respondents. However, this

study may act as a preliminary survey due to the

scarcity of published data regarding the

reproductive health of Orang Asli women.

CONCLUSION

The practice of home delivery is still common

among the respondents and a high proportion of

them came late for their antenatal booking. These

two practices were significantly associated with

poor attitude regarding antenatal care. Their

knowledge on certain aspects of antenatal care

were still poor especially regarding the importance

of early antenatal check-up, health screening and

complications related to diabetes and hypertension

in pregnancy. Specific intervention programme

customized to the Orang Asli community need to be

planned and conducted in order to improve their

maternal health practices and eventually improve

the health status of the Orang Asli women.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank and acknowledge the 2 nd

Year Medical Students Group C2 (2010/2011) of

Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti

Putra Malaysia for their involvement during the

initial data collection of the study.

REFERENCES

1. World Bank. Safe Motherhood- a review. The

Safe Motherhood Initiatives, 1987 - 2005 World

Bank Report. New York: Family Care

International, 2007.

2. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Family Health

Development Division. Perinatal care manual:

antenatal care. (2nd ed). Ministry of Health

Malaysia: Putrajaya, 2010.

3. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Annual Report of

the Family Health Development Division, 2006.

Family Health Development Division, Ministry of

Health Malaysia: Putrajaya, 2007.

4. Anderson I, Crengle S, Kamaka ML, Chen TH,

Palafox N, Pulver LJ. Indigenous health in

Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific. Lancet

2006; 367:1775-1785.

5. Islam MR, Odland JO. Determinants of

antenatal and postnatal care visits among

Indigenous people in Bangladesh: a study of the

Mru Community. Rural and remote health.

2011.

11:1672.

Available

from:

http://www.rrh.org.au (accessed 22 August

2011).

6. Department of Orang Asli Affair, Malaysia.

Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine 2011, Vol. 11(2): 13-21

Annual Report of the Department of Orang Asli

Affair, Malaysia. Annual Report of the

Department of Orang Asli Affair. Kuala Lumpur,

2008.

17. Gabrysch S, Lema C, Bedrinana E et al. Cultural

adaptation of birthing services in rural

Ayacucho, Peru. Bull World Health Organ

2009; 87: 724-729.

7. Nicholas C, Baer A. Health care for the Orang

Asli. In: Chee HL, Barraclough S. (eds). Health

care in Malaysia. p. 119-136. London:

Routledge, 2007.

18. Kaddour A, Hafez R, Zurayk H. Womens

perception of reproductive health in three

communities around Beirut, Lebanon. Reprod

Health Matters 2005; 13(25): 34-42.

8. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Negeri Sembilan

Health Department Report on Maternal

Mortality for 2009. Seremban: Negeri Sembilan

State Health Department, 2010.

19. Zhao Q, Kulane A, Gao Y et al. Knowledge and

attitude on maternal health care among ruralto-urban migrant women in Shanghai, China.

BMC Womens Health. 2009. 9:5. Available

from:

http://www.biomedcentral.com

(accessed 6 May 2011).

9. Lim HM, Chee HL. Nutritional status and

reproductive health of Orang Asli women in two

villages in Kuantan, Pahang. Malaysian J Nutr.

1998; 4: 31-54.

10. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Report on

antenatal care attendance for Jempol District

in 2010. Seremban: Negeri Sembilan State

Health Department, 2011.

11. IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics Version 19. IBM

Corp: New York, 2010.

12. Rumbold AR, Bailie RS, Si D et al. Delivery of

maternal healthcare in indigenous primary

health care services: baseline data for an

ongoing quality improvement initiative. BMC

Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2011. 11:16.

Available

from:

http://www.biomedcentral.com (accessed 21

April 2011).

13. Norhayati M, Noor Hayati MI, Nor Fariza N et al.

Health status of Orang Asli (aborigine)

community in Pos Piah, Sungai Siput, Perak,

Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public

Health 1998; 29(1): 58-61.

14. Zalilah MS, Tham BL. Food security and child

nutritional status among Orang Asli (Temuan)

households in Hulu Langat, Selangor. Med J

Malaysia 2002; 57: 1-6.

15. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Report on the

Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Death in

Malaysia,

2001

-2005.

Family

Health

Development Division: Putrajaya, 2008.

16. Sivalingam N. Maternal health care at the

crossroads. Med J Malaysia 2003; 58(1): 1-4.

You might also like

- Barthel Index (0-20)Document2 pagesBarthel Index (0-20)Yessika Adelwin Natalia95% (19)

- Review of Systems Cheat SheetDocument2 pagesReview of Systems Cheat Sheetarmymedic7No ratings yet

- Medical Response to Child Sexual Abuse: A Resource for Professionals Working with Children and FamiliesFrom EverandMedical Response to Child Sexual Abuse: A Resource for Professionals Working with Children and FamiliesNo ratings yet

- Health Sector Reform Agenda in The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesHealth Sector Reform Agenda in The PhilippinesSoc John Magtuba100% (1)

- 408 955 1 PBDocument6 pages408 955 1 PBmohamad safiiNo ratings yet

- Antenatal Care in Urban AreaDocument6 pagesAntenatal Care in Urban AreamanalNo ratings yet

- Artikel Prasetyo.4Document10 pagesArtikel Prasetyo.4iib ristuNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Antenatal Care Utilization in Yem PDFDocument7 pagesFactors Affecting Antenatal Care Utilization in Yem PDFNuridha FauziyahNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Karakteristik Ibu Dengan Pengetahuan Tentang Penatalaksanaan Diare Pada BalitaDocument8 pagesHubungan Karakteristik Ibu Dengan Pengetahuan Tentang Penatalaksanaan Diare Pada BalitaRafly SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Breastfeeding Practices Among Mothers in Lafia LocalDocument13 pagesFactors Influencing Breastfeeding Practices Among Mothers in Lafia LocalCha Tozenity ChieNo ratings yet

- Differentials in Maternal Health Care Service UtilDocument10 pagesDifferentials in Maternal Health Care Service UtilJudith DavisNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument51 pagesChapter IAdhish khadkaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Kanser ServiksDocument21 pagesJurnal Kanser Servikskucing botak0% (1)

- Assessment of The Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Residents at Tikur Anbesa Hospital About Preconceptional Care 2018Document10 pagesAssessment of The Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Residents at Tikur Anbesa Hospital About Preconceptional Care 2018nadyanatasya7No ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Exclusive Breastfeeding Practice in Rural Communities of Cross River State, NigeriaDocument10 pagesFactors Affecting Exclusive Breastfeeding Practice in Rural Communities of Cross River State, NigeriaJustina Layo AgunloyeNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Vulva HygienDocument10 pagesJurnal Vulva HygienDinaMerianaVanrioNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument11 pagesResearch ArticleJabou NjieNo ratings yet

- Impact of Health Education Intervention On Knowledge of Safe Motherhood Among Women of Reproductive Age in Eleme, Rivers State, NigeriaDocument13 pagesImpact of Health Education Intervention On Knowledge of Safe Motherhood Among Women of Reproductive Age in Eleme, Rivers State, Nigerialivesource technologyNo ratings yet

- First Year M.Sc. Nursing, Bapuji College of Nursing, Davangere - 4, KarnatakaDocument13 pagesFirst Year M.Sc. Nursing, Bapuji College of Nursing, Davangere - 4, KarnatakaJalajarani AridassNo ratings yet

- Anemia in Pregnancy in Malaysia: A Cross-Sectional Survey: Original ArticleDocument10 pagesAnemia in Pregnancy in Malaysia: A Cross-Sectional Survey: Original ArticleThomson AffendyNo ratings yet

- Neonatal JaundiceDocument5 pagesNeonatal JaundiceKartik KumarasamyNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Karakteristik Ibu Dengan Pengetahuan Tentang Penatalaksanaan Diare Pada BalitaDocument8 pagesHubungan Karakteristik Ibu Dengan Pengetahuan Tentang Penatalaksanaan Diare Pada BalitaArisa CaNo ratings yet

- Rodiyah Mulyadi (Tugas ANC, InC, PNC)Document40 pagesRodiyah Mulyadi (Tugas ANC, InC, PNC)adelacalistaaNo ratings yet

- JPMA (Journal of Pakistan Medical Association) Vol 53, No.2, Feb. 2003Document10 pagesJPMA (Journal of Pakistan Medical Association) Vol 53, No.2, Feb. 2003Gheavita Chandra DewiNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Newborn Care Knowledge and Practices in The Upper HimalayasDocument18 pagesFactors Associated With Newborn Care Knowledge and Practices in The Upper Himalayasmente ethiopiaNo ratings yet

- Antenatal CareDocument10 pagesAntenatal CareBachtiar M TaUfikNo ratings yet

- Harry Potter and The Deathly Hallows (Russian)Document5 pagesHarry Potter and The Deathly Hallows (Russian)Te HineahuoneNo ratings yet

- The Study of Breastfeeding Knowledge Among Northern Iranian TeachersDocument5 pagesThe Study of Breastfeeding Knowledge Among Northern Iranian TeachersyusufNo ratings yet

- Physical and Psychosocial Impacts of Pregnancy On Adolescents and Their Coping Strategies A Descriptive Study in Kuala Lumpur Malaysia PDFDocument9 pagesPhysical and Psychosocial Impacts of Pregnancy On Adolescents and Their Coping Strategies A Descriptive Study in Kuala Lumpur Malaysia PDFJason Jimmy Lee PillayNo ratings yet

- Isqr PDFDocument7 pagesIsqr PDFOmy NataliaNo ratings yet

- Health Behaviors of Primigravida TeenagersDocument6 pagesHealth Behaviors of Primigravida TeenagersAubrey UniqueNo ratings yet

- Profile of Women With Late Menstrual Period: Profil Perempuan Yang Mengalami Keterlambatan HaidDocument5 pagesProfile of Women With Late Menstrual Period: Profil Perempuan Yang Mengalami Keterlambatan HaidRizki WulandariNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 15 02450 PDFDocument14 pagesIjerph 15 02450 PDFDeby WicaksonoNo ratings yet

- Awareness and Utilization of PapDocument12 pagesAwareness and Utilization of Paparun koiralaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Uterine Prolapse in NepalDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Uterine Prolapse in Nepaleyewhyvkg100% (1)

- Anaemia in Pregnancy Malaysia, APJCN2006 PDFDocument10 pagesAnaemia in Pregnancy Malaysia, APJCN2006 PDFAkhmal SidekNo ratings yet

- AstateDocument4 pagesAstateJalajarani AridassNo ratings yet

- Applied - Evaluation of Knowledge of Husbands - Oluseyi Oa AtandaDocument10 pagesApplied - Evaluation of Knowledge of Husbands - Oluseyi Oa AtandaImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- A Cross-Sectional Analytic Study of Postpartum Health Care Service Utilization in The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesA Cross-Sectional Analytic Study of Postpartum Health Care Service Utilization in The Philippineskristynellebonifacio7051No ratings yet

- Maternal Mortality and Contributing Risk Factors: Kematian Maternal Dan Faktor-Faktor Risiko Yang MempengaruhinyaDocument6 pagesMaternal Mortality and Contributing Risk Factors: Kematian Maternal Dan Faktor-Faktor Risiko Yang Mempengaruhinyanarto_chemz1013No ratings yet

- Ajpherd v19 Supp1 A2 PDFDocument9 pagesAjpherd v19 Supp1 A2 PDFJennybabe PizonNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Antenatal Care Package On Knowledge of Pregnancy Induced HypertensionDocument3 pagesEffectiveness of Antenatal Care Package On Knowledge of Pregnancy Induced Hypertensionazida90No ratings yet

- Timely Utilization of Parental Care For Young WomenDocument17 pagesTimely Utilization of Parental Care For Young Womenyatta yattaNo ratings yet

- Utilization and Effect of Traditional Birth Attendants Among The Pregnant Women in Kahoora Division Hoima DistrictDocument13 pagesUtilization and Effect of Traditional Birth Attendants Among The Pregnant Women in Kahoora Division Hoima DistrictKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- 5593-Article Text-79579-1-10-20220914Document9 pages5593-Article Text-79579-1-10-20220914Eunice PalloganNo ratings yet

- Hormonal Profile of Women With Primary Infertility in A Tertiary Healthcare SettingDocument7 pagesHormonal Profile of Women With Primary Infertility in A Tertiary Healthcare Settingijmb333No ratings yet

- Partus LamaDocument8 pagesPartus LamaSulis SipinNo ratings yet

- Vvvvv95 PDFDocument7 pagesVvvvv95 PDFchelsea ledyfiaNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Health Status of Adolescent Girls ResidingDocument120 pagesA Study On The Health Status of Adolescent Girls Residingsusmithamuni100% (6)

- Common Perinatal Mental Disorders in Northern Viet Nam: Community Prevalence and Health Care UseDocument9 pagesCommon Perinatal Mental Disorders in Northern Viet Nam: Community Prevalence and Health Care UseFeronika TerokNo ratings yet

- McDonald Et Al-2015-BJOG - An International Journal of Obstetrics & GynaecologyDocument8 pagesMcDonald Et Al-2015-BJOG - An International Journal of Obstetrics & GynaecologyKevin LoboNo ratings yet

- Embriologi Semester Viii 2019Document11 pagesEmbriologi Semester Viii 2019AmiNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Pregnancy Outcomes in Morogoro Municipality, TanzaniaDocument12 pagesFactors Influencing Pregnancy Outcomes in Morogoro Municipality, Tanzaniainal2008No ratings yet

- Ing GrisDocument6 pagesIng GrisDiny Nur FauziahNo ratings yet

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences Bangalore KarnatakaDocument18 pagesRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences Bangalore Karnatakapallavi sharmaNo ratings yet

- Unplanned Pregnancy and Its Associated FactorsDocument11 pagesUnplanned Pregnancy and Its Associated Factorskenny. hyphensNo ratings yet

- Tanslate 1Document7 pagesTanslate 1Lara.syukmaHaraNo ratings yet

- Caroline Complete ProjectDocument60 pagesCaroline Complete ProjectDaniel emmanuelNo ratings yet

- Wong2010Document4 pagesWong2010dara intanNo ratings yet

- 13 Ashwinee EtalDocument5 pages13 Ashwinee EtaleditorijmrhsNo ratings yet

- Anemia Among Antenatal Mother in Urban MalaysiaDocument6 pagesAnemia Among Antenatal Mother in Urban MalaysiaOmy NataliaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions of Preeclampsia Among First-Generation Nigerian Women in the United StatesFrom EverandKnowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions of Preeclampsia Among First-Generation Nigerian Women in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of PneumoniaDocument2 pagesPathophysiology of PneumoniaJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- NCSBN's Reviews For The NCLEX-RN & Nclex-PN: Weekly Study PlanDocument3 pagesNCSBN's Reviews For The NCLEX-RN & Nclex-PN: Weekly Study PlanJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- CE Mild Traumatic Brain Injury.24Document7 pagesCE Mild Traumatic Brain Injury.24Jesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- Efficiency of Care and Satisfaction For Head Injury Patients at Emergency Department in Mansoura Emergency HospitalDocument11 pagesEfficiency of Care and Satisfaction For Head Injury Patients at Emergency Department in Mansoura Emergency HospitalJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- 857 1857 1 PBDocument4 pages857 1857 1 PBJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- European Down Syndrome Association: February 2016Document7 pagesEuropean Down Syndrome Association: February 2016Jesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- Wvsu Scholarship f09Document2 pagesWvsu Scholarship f09Jesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- Metronidazole Ds Case Pre 4th YrDocument2 pagesMetronidazole Ds Case Pre 4th YrJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts On Communityacquired Bacterial Pneumonia in PediatricsDocument6 pagesBasic Concepts On Communityacquired Bacterial Pneumonia in PediatricsJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- SultamicillinDocument2 pagesSultamicillinJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- Problem ListDocument1 pageProblem ListJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- BoneDocument5 pagesBoneJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- 222 765 1 PBDocument8 pages222 765 1 PBJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- Down Syndrome (DS) and Hirschsprung's Disease (HSCR)Document3 pagesDown Syndrome (DS) and Hirschsprung's Disease (HSCR)Jesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- PathoPhysiology of Hypertension DiagramDocument4 pagesPathoPhysiology of Hypertension DiagramKat Taasin100% (1)

- Care of Patient With Copd: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseDocument32 pagesCare of Patient With Copd: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- SCR 200 Nursing Care Plan TWDocument6 pagesSCR 200 Nursing Care Plan TWJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- ReadmeDocument2 pagesReadmeJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- NCP CVA Activity IntoleranceDocument2 pagesNCP CVA Activity IntoleranceJesselle LasernaNo ratings yet

- Schematic Diagram of Pleural EffusionDocument2 pagesSchematic Diagram of Pleural EffusionJesselle Laserna0% (1)

- Antenatal Management of Low Lying Placenta 4.0Document6 pagesAntenatal Management of Low Lying Placenta 4.0ubayyumrNo ratings yet

- Vaccine: Contents Lists Available atDocument9 pagesVaccine: Contents Lists Available atShabrina Amalia SuciNo ratings yet

- CHCECE031 Knowledge TaskDocument19 pagesCHCECE031 Knowledge Taskho.nafisiNo ratings yet

- Kunjungan Agustus 2022Document42 pagesKunjungan Agustus 2022Klinik dr. DarlinaNo ratings yet

- Norovirus Public Health Fact SheetDocument2 pagesNorovirus Public Health Fact SheetClickon DetroitNo ratings yet

- GDM Case StudyDocument5 pagesGDM Case Studydheeptha sundarNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Uterine Actions - Monika MakwanaDocument10 pagesAbnormal Uterine Actions - Monika Makwanamonika makwanaNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors Breast Cancer Report FinalDocument361 pagesRisk Factors Breast Cancer Report FinalNurhidayahAzizNo ratings yet

- Asuhan Keperawatan Pasien Dengan Sepsis: Ns. Anastasia Hardyati., M.Kep., Sp. KMBDocument17 pagesAsuhan Keperawatan Pasien Dengan Sepsis: Ns. Anastasia Hardyati., M.Kep., Sp. KMBchika wahyu sasqiautamiNo ratings yet

- HIV Counselling and Testing: Dr. Kanupriya Chturvedi Dr. S.K.ChaturvediDocument22 pagesHIV Counselling and Testing: Dr. Kanupriya Chturvedi Dr. S.K.ChaturvedikaranNo ratings yet

- 2) Risk Assessment, PCI Plan, SMART Goals BMS 6-2 Day 1Document70 pages2) Risk Assessment, PCI Plan, SMART Goals BMS 6-2 Day 1Basma AzazNo ratings yet

- Plumbing Design Service ProposalDocument2 pagesPlumbing Design Service ProposalChristan Daniel RestorNo ratings yet

- Subject Plan B.SC Nursing 1 Year: MicrobiologyDocument2 pagesSubject Plan B.SC Nursing 1 Year: MicrobiologySandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis b-1Document7 pagesHepatitis b-1api-550162163No ratings yet

- Diabetes Among HIV-Infected Patients On Antiretroviral Therapy at Mulago National Referral Hospital in Central UgandaDocument6 pagesDiabetes Among HIV-Infected Patients On Antiretroviral Therapy at Mulago National Referral Hospital in Central Ugandassentongo JohnmaryNo ratings yet

- Assisting With Dilatation and Curettage ProcedureDocument3 pagesAssisting With Dilatation and Curettage ProceduremanjuNo ratings yet

- Minor Disorders of The NewbornDocument2 pagesMinor Disorders of The NewbornMandeep Kaur50% (2)

- POLS 1503 Study Guide PDFDocument15 pagesPOLS 1503 Study Guide PDFHymns ChurchNo ratings yet

- FAMILY HEALTH SURVEY FORM Miraato Mataid 2Document7 pagesFAMILY HEALTH SURVEY FORM Miraato Mataid 2Micmic Mira-atoNo ratings yet

- Gynaecology Examination PRAVEENADocument15 pagesGynaecology Examination PRAVEENAPraveena MoganNo ratings yet

- Artificial Method of ContraceptionDocument7 pagesArtificial Method of ContraceptionCasey AbelloNo ratings yet

- Terms in ObstetricsDocument22 pagesTerms in ObstetricsYovi pransiska JambiNo ratings yet

- MCQ Tropmed 2Document1 pageMCQ Tropmed 2Dapot SianiparNo ratings yet

- Analisis Pendekatan Sanitasi Dalam Menangani Stunting (Studi Literatur) Syamsuddin S, Ulfa Zafirah AnisahDocument7 pagesAnalisis Pendekatan Sanitasi Dalam Menangani Stunting (Studi Literatur) Syamsuddin S, Ulfa Zafirah AnisahVania Petrina CalistaNo ratings yet

- 3 Conditions To Watch For After Childbirth: 1. Postpartum PreeclampsiaDocument4 pages3 Conditions To Watch For After Childbirth: 1. Postpartum PreeclampsiaM. MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Namulaba Annual Report August 2015 To July 2016 FINALDocument19 pagesNamulaba Annual Report August 2015 To July 2016 FINALSamuel KalibalaNo ratings yet

- Guevara OTH520 Ticket4Document3 pagesGuevara OTH520 Ticket4rubynavagNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan Risk For Uterine InfectionDocument4 pagesNursing Care Plan Risk For Uterine Infectionderic97% (30)

- Discharge PlanDocument2 pagesDischarge PlanJude Labajo100% (1)