Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Orobator Out of Africa America 5 November 2012

Uploaded by

jassonmujicaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Orobator Out of Africa America 5 November 2012

Uploaded by

jassonmujicaCopyright:

Available Formats

America Magazine - Out of Africa

Page 1 of 3

Out of Africa

How a new generation of theologians is reshaping the church

AGBONKHIANMEGHE E. OROBATOR | NOVEMBER 5, 2012

Digg

Facebook

Seed Newsvine

fricas theological landscape is changing significantly and

rapidly. The pace and scope of this transformation came

into focus at the first regional conference of the global

network of Catholic Theological Ethics in the World Church held

in Nairobi, Kenya, in August 2012. For three days, 35 African

theologians engaged in intense conversation about pressing

issues confronting church and society in Africa from the

perspective of theological ethics. By many accounts this

inaugural gathering did not resemble the usual theological talkshop where scholars present abstract theses or ecclesiastical leaders declaim lofty doctrinal

propositions. Judging by its composition, methodology and focus, the conference offered a glimpse of

the shape of theology in Africa today and the promise it holds for the world church.

Three factors illustrate this phenomenon of change in theological discourse and scholarship. The first

factor relates to demographics. Picture this: Nearly half the participants at the C.T.E.W.C. conference in

Nairobi were women, both lay and religious. This is something new and different. A gathering of

theologians where women are not in the minority is unprecedented in Africa. It would have been

customary to have, at most, only token representation. Among the women theologians in attendance at

the Nairobi conference, seven are in a C.T.E.W.C.-sponsored program for the advanced training of

African women in theological ethics. This program will enable all of them to earn doctoral degrees in

theological ethics from African universities within the next three years. A new generation of African

women theologians is in the making across an ecclesial and theological landscape where hitherto they

were unrepresented, their voices ignored and their contributions unacknowledged.

As the veil of invisibility lifts, African women are taking a critical stand on existential issues in church

and society. They make their own arguments as scholars with passion, confidence and authority rather

than being spoken about as passive objects in theological conferences and workshops conducted and

dominated by male theologians. It should hardly surprise us that this new generation of theologically

literate African women expresses its understanding of faith and the concomitant ramifications for civil

and religious society in a new and radical way. They open up new paths toward an action-orientated

theological enterprise.

The advanced theological education of African women responds to one of the recommendations of the

Second Synod of Bishops for Africa, held in 2009, for the formation and greater integration of women

into church structures and decision-making processes. Judging by the tone and scope of the discourse

at the Nairobi gathering, integration would not necessarily translate into unquestioning and submissive

acceptance of subservient roles, to which many African women are confined in church and society. As a

result of the theological formation of African women, we can expect to see an intensifying theological

advocacy for the just treatment of women in Africa; honest recognition and appreciation of their dignity

http://www.americamagazine.org/content/article.cfm?article_id=13672

11/13/2012

America Magazine - Out of Africa

Page 2 of 3

and contribution to society; and constructive harnessing of their talents and resources for leadership,

ministry and participation in both the African and the world church.

A New Way of Doing Theology

A second sign of change on Africas theological landscape is a palpable sense of energy and creativity.

Among the participants at the Nairobi conference, the majority received their doctorates in theology

less than five years ago. This means that a new generation of African theologians has emerged, primed

to receive the mantle from the more seasoned generation of theologians who negotiated the transition

from a colonial church to a truly African church, but ready to steer this church in a new and exciting

direction.

The format of the conference took the shape of conversationwomen and men, lay and religious, young

and old exploring and raising probing questions, clearing new paths and articulating viable options. A

critical component of this approach is readiness to listen and learn from one another. The setting of the

conference recalled the African palaver model of dialogue and consensus in addressing pertinent

theological and ethical issues. This conversation was led by new African scholars in dialogue with

established scholars and ecclesial leaders. Archbishop John Onaiyekan of Abuja, Nigeria; Archbishop

John Baptist Odama of Gulu, Uganda; and Bishop Eduardo Hiiboro Kussala of Tombura-Yambio, South

Sudan, all attended the conference. Unusually, they participated not as keynote speakers but as

conversation partners. In this role, the ecclesial leaders contributed to and enriched the conversation by

offering candid views and relating moving personal testimonies of their experience of reconciliation,

justice and peace in Africa. Here, again, something new is emerging across the continent: it is not

customary for theologians to dialogue with ecclesial leaders on level ground.

A third striking feature of the conference was the variety of issues addressed by participants. On the

agenda were the themes of the Second African Synod: reconciliation, justice and peace. Any observer of

Africa and its predicament would understand why these themes are crucial for the church in Africa, a

continent reeling from the trauma of ethnic division, economic mismanagement, human rights abuses,

political bigotry and civil and sectarian violence. These crises affect the lives of all Africans. The ability

and willingness of African theologians to tackle these vexing ethical challenges is a measure of the

credibility and relevance of Catholic theology in Africa. The concerns of the conference participants

reflect the concerns of contemporary theologians in the wider ecclesia in Africa. They go beyond the

borders of church doctrine and discipline and relate to public and existential concerns. The catalog of

concerns ranges from sociopolitical unrest in Northern Uganda and Ivory Coast to economic injustice

endemic in the mining industries in Congo and Nigeria; from sexual, gender-based violence in South

Africa and South Sudan to ethnic, religious and sectarian violence in Kenya and Egypt. Current

conversations in theological ethics in Africa do not shy away from these complex ethical issues. Yet it

would be mistaken to think that the focus is simply ad extra.

Justice in the Church

Also at issue are internal ecclesial concerns, such as the role and participation of African women in the

church. Official rhetoric of participation, equality and gender justice in church is not lacking;

oftentimes, it is stirring. But too often it remains at the level of rhetoric. African women theologians are

leading the way not only in formulating a critical appraisal of the ecclesiastical status quo, but also in

articulating alternatives to an inherited theological discourse that favors patriarchy and clericalism.

There is growing recognition that the quest for reconciliation, justice and peace is as pressing for the

church as it is for the wider society. And this quest cannot bypass or overlook homegrown solutions.

This presents African theologians with a formidable, multifaceted task: first, to explore and identify

these potential solutions; second, to articulate and analyze them systematically in conversation with the

Christian tradition and Catholic social teaching; and, third, to propose workable models and

applications at the service of the churchs mission in a postmodern, globalizing world.

http://www.americamagazine.org/content/article.cfm?article_id=13672

11/13/2012

America Magazine - Out of Africa

Page 3 of 3

Those familiar with the African theological landscape would naturally link this methodology to

inculturation. The three-stage process outlined above follows that familiar pattern. What is different is

that the issues at stake are not just matters of sacramental and liturgical practice that have prompted

some theologians to narrowly and erroneously depict the church in Africa merely as the dancing

church. This stereotypical portrayal of what church is and does in Africa flies in the face of what

African Catholic theologians are talking about. The discourse has shifted. A quick sample of topics

discussed at the Nairobi conference is enough to remove any lingering doubt.

Alison Munro, the South African nun who leads the H.I.V./AIDS Office of the Southern African Catholic

Bishops Conference, demonstrated how the daunting task of dealing with the AIDS pandemic in South

Africa is integral to the churchs mission of justice and peace. The Nigerian-American scholar Anne

Arabome made a powerful argument in favor of justice as a practice that thrives only when women and

men are accorded equal dignity in church and society. One of the seven C.T.E.W.C. scholarship

recipients, Anne Oyier, drew on personal experience of sectarian violence to argue persuasively the case

of holistic peace education as the path toward effective reconciliation and lasting peace in Africa. Elise

Rutagambwa, S.J., offered a model for overcoming the tension between the quest for justice and the

necessity of reconciliation in concrete instances of violence, like those in Northern Uganda and Rwanda.

And David Kaulemu, a Zimbabwean lay theologian, proffered a methodology for promoting social

justice founded on mutuality and collaboration between the church and civil society in Africa.

There can be no question about the strong and dynamic currents that are now shaping the flow of

theological discourse in Africa. A unique characteristic of this discourse is the widening circle of

conversation partners. African theologians no longer content themselves with talking to like-minded

theologians; they are talking to bishops, civil society groups and government representatives. This

approach represents a new way of doing theology, in which collaboration and conversation are

preferred over confrontation. The result is a process of mutual listening and learning, a vital ingredient

for constructing what the veteran African theologian Elochukwu Uzukwu once designated as the

listening church.

The Nairobi conference offers a new understanding of the nature and purpose of theology in Africa and

in the world church. First, theology resembles a team event where the rules of engagement favor

conversation over confrontation, even in the midst of tumultuous and neuralgic debates in church and

society.

Second, theology is work in progress informed by on-the-ground realities. It is not about discussing

arcane points of doctrine or resisting critical analysis. Theology embodies and delineates a shared space

large enough to accommodate multiple quests to (re)interpret Christian tradition and Scripture through

sincere and respectful dialogue in the unfolding context of church, society and the academy. In this

space openness to personal conversion would seem a precondition for effective dialogue and action.

Finally, there is a generational turnover that recognizes the wisdom and legacy of established

theologians but celebrates the promise and vitality of young theologians intent on furthering the

mission of the world church. On the evidence of the dynamics and demographics of this generational

turnover in African theology, we would be right to proclaim with Pliny the Elder: There is always

something new out of Africa!

Read excerpts from the CTEWC conference.

Agbonkhianmeghe E. Orobator, S.J., the provincial superior of the Eastern Africa Province of

the Society of Jesus, is a lecturer at Hekima College in Nairobi, Kenya.

http://www.americamagazine.org/content/article.cfm?article_id=13672

11/13/2012

You might also like

- The Church and Development in Africa, Second Edition: Aid and Development from the Perspective of Catholic Social EthicsFrom EverandThe Church and Development in Africa, Second Edition: Aid and Development from the Perspective of Catholic Social EthicsNo ratings yet

- Foundations for African Theological Ethics: A Contemporary Rural African PerspectiveFrom EverandFoundations for African Theological Ethics: A Contemporary Rural African PerspectiveNo ratings yet

- The Post-Conciliar Church in Africa: No Turning Back the ClockFrom EverandThe Post-Conciliar Church in Africa: No Turning Back the ClockNo ratings yet

- The Church as Salt and Light: Path to an African Ecclesiology of Abundant LifeFrom EverandThe Church as Salt and Light: Path to an African Ecclesiology of Abundant LifeNo ratings yet

- Is Africa Incurably Religious?: Secularization and Discipleship in AfricaFrom EverandIs Africa Incurably Religious?: Secularization and Discipleship in AfricaNo ratings yet

- Communion Ecclesiology and Social Transformation in African Catholicism: Between Vatican Council II and African Synod IIFrom EverandCommunion Ecclesiology and Social Transformation in African Catholicism: Between Vatican Council II and African Synod IINo ratings yet

- Toward an African Theology of Fraternal Solidarity: UBE NWANNEFrom EverandToward an African Theology of Fraternal Solidarity: UBE NWANNENo ratings yet

- Challenges Facing the Orthodox Church Movements in East AfricaFrom EverandChallenges Facing the Orthodox Church Movements in East AfricaNo ratings yet

- Christian Spirituality in Africa: Biblical, Historical, and Cultural Perspectives from KenyaFrom EverandChristian Spirituality in Africa: Biblical, Historical, and Cultural Perspectives from KenyaNo ratings yet

- An Introduction to Theology in Africa and the Kpelelogical Foundations of Christian TheologyFrom EverandAn Introduction to Theology in Africa and the Kpelelogical Foundations of Christian TheologyNo ratings yet

- African Pentecostalism and World Christianity: Essays in Honor of J. Kwabena Asamoah-GyaduFrom EverandAfrican Pentecostalism and World Christianity: Essays in Honor of J. Kwabena Asamoah-GyaduNo ratings yet

- Life Under the Baobab Tree: Africana Studies and Religion in a Transitional AgeFrom EverandLife Under the Baobab Tree: Africana Studies and Religion in a Transitional AgeNo ratings yet

- Making Disciples in Africa: Engaging Syncretism in the African Church through Philosophical Analysis of WorldviewsFrom EverandMaking Disciples in Africa: Engaging Syncretism in the African Church through Philosophical Analysis of WorldviewsNo ratings yet

- From Historical to Critical Post-Colonial Theology: The Contribution of John S. Mbiti and Jesse N. K. MugambiFrom EverandFrom Historical to Critical Post-Colonial Theology: The Contribution of John S. Mbiti and Jesse N. K. MugambiNo ratings yet

- Historical and Social Dimensions in African Christian Theology: A Contemporary ApproachFrom EverandHistorical and Social Dimensions in African Christian Theology: A Contemporary ApproachNo ratings yet

- Global Renewal Christianity: Spirit-Empowered Movements: Past, Present and FutureFrom EverandGlobal Renewal Christianity: Spirit-Empowered Movements: Past, Present and FutureNo ratings yet

- The Transformation of African Christianity: Development and Change in the Nigerian ChurchFrom EverandThe Transformation of African Christianity: Development and Change in the Nigerian ChurchNo ratings yet

- Akan Christology: An Analysis of the Christologies of John Samuel Pobee and Kwame Bediako in Conversation with the Theology of Karl BarthFrom EverandAkan Christology: An Analysis of the Christologies of John Samuel Pobee and Kwame Bediako in Conversation with the Theology of Karl BarthNo ratings yet

- Identity and Ecclesiology: Their Relationship among Select African TheologiansFrom EverandIdentity and Ecclesiology: Their Relationship among Select African TheologiansNo ratings yet

- Pastoral Care, Health, Healing, and Wholeness in African Contexts: Methodology, Context, and IssuesFrom EverandPastoral Care, Health, Healing, and Wholeness in African Contexts: Methodology, Context, and IssuesNo ratings yet

- Benefaction and Patronage in Leadership: A Socio-Historical Exegesis of the Pastoral EpistlesFrom EverandBenefaction and Patronage in Leadership: A Socio-Historical Exegesis of the Pastoral EpistlesNo ratings yet

- Theology of Reconciliation in the Context of Church Relations: A Palestinian Christian Perspective in Dialogue with Miroslav VolfFrom EverandTheology of Reconciliation in the Context of Church Relations: A Palestinian Christian Perspective in Dialogue with Miroslav VolfNo ratings yet

- Christian identity and justice in a globalized world from a Southern African perspectiveFrom EverandChristian identity and justice in a globalized world from a Southern African perspectiveNo ratings yet

- Kwame Bediako and African Christian Scholarship: Emerging Religious Discourse in Twentieth-Century GhanaFrom EverandKwame Bediako and African Christian Scholarship: Emerging Religious Discourse in Twentieth-Century GhanaNo ratings yet

- Re-Imaging Modernity: A Contextualized Theological Study of Power and Humanity witin Akamba Christianity in KenyaFrom EverandRe-Imaging Modernity: A Contextualized Theological Study of Power and Humanity witin Akamba Christianity in KenyaNo ratings yet

- African Catholicism and Hermeneutics of Culture: Essays in the Light of African Synod IIFrom EverandAfrican Catholicism and Hermeneutics of Culture: Essays in the Light of African Synod IINo ratings yet

- Good Pastors, Bad Pastors: Pentecostal Ministerial Ethics in GhanaFrom EverandGood Pastors, Bad Pastors: Pentecostal Ministerial Ethics in GhanaNo ratings yet

- Religious Crisis and Civic Transformation: How Conflicts over Gender and Sexuality Changed the West German Catholic ChurchFrom EverandReligious Crisis and Civic Transformation: How Conflicts over Gender and Sexuality Changed the West German Catholic ChurchNo ratings yet

- Early Christianity: A Textbook for African StudentsFrom EverandEarly Christianity: A Textbook for African StudentsNo ratings yet

- Engaging Religions and Worldviews in Africa: A Christian Theological MethodFrom EverandEngaging Religions and Worldviews in Africa: A Christian Theological MethodNo ratings yet

- The Maturing Church: An Integrated Approach to Contextualization, Discipleship and MissionFrom EverandThe Maturing Church: An Integrated Approach to Contextualization, Discipleship and MissionNo ratings yet

- The Mystery of the Church: Applying Paul’s Ecclesiology in AfricaFrom EverandThe Mystery of the Church: Applying Paul’s Ecclesiology in AfricaNo ratings yet

- Under the Palaver Tree: Doing African Ecclesiology in the Spirit of Vatican II—the Contributions of Elochukwu E. UzukwuFrom EverandUnder the Palaver Tree: Doing African Ecclesiology in the Spirit of Vatican II—the Contributions of Elochukwu E. UzukwuNo ratings yet

- The Making of an African Christian Ethics: Bénézet Bujo and the Roman Catholic Moral TraditionFrom EverandThe Making of an African Christian Ethics: Bénézet Bujo and the Roman Catholic Moral TraditionNo ratings yet

- Negotiating Identity: Exploring Tensions between Being Hakka and Being Christian in Northwestern TaiwanFrom EverandNegotiating Identity: Exploring Tensions between Being Hakka and Being Christian in Northwestern TaiwanNo ratings yet

- Theologizing in Black: On Africana Theological Ethics and AnthropologyFrom EverandTheologizing in Black: On Africana Theological Ethics and AnthropologyNo ratings yet

- Who Do the Ngimurok Say That They Are?: A Phenomenological Study of Turkana Traditional Religious Specialists in Turkana, KenyaFrom EverandWho Do the Ngimurok Say That They Are?: A Phenomenological Study of Turkana Traditional Religious Specialists in Turkana, KenyaNo ratings yet

- Woman as Mother and Wife in the African Context of the Family in the Light of John Paul Ii’S Anthropological and Theological Foundation: The Case Reflected Within the Bantu and Nilotic Tribes of KenyaFrom EverandWoman as Mother and Wife in the African Context of the Family in the Light of John Paul Ii’S Anthropological and Theological Foundation: The Case Reflected Within the Bantu and Nilotic Tribes of KenyaNo ratings yet

- The Eucharist as a Countercultural Liturgy: An Examination of the Theologies of Henri de Lubac, John Zizioulas, and Miroslav VolfFrom EverandThe Eucharist as a Countercultural Liturgy: An Examination of the Theologies of Henri de Lubac, John Zizioulas, and Miroslav VolfNo ratings yet

- Missiology Reimagined: The Missions Theology of the Nineteenth-Century African American MissionaryFrom EverandMissiology Reimagined: The Missions Theology of the Nineteenth-Century African American MissionaryNo ratings yet

- Reframing the House: Constructive Feminist Global Ecclesiology for the Western Evangelical ChurchFrom EverandReframing the House: Constructive Feminist Global Ecclesiology for the Western Evangelical ChurchNo ratings yet

- Women and Christian Mission: Ways of Knowing and Doing TheologyFrom EverandWomen and Christian Mission: Ways of Knowing and Doing TheologyNo ratings yet

- Africa Bears Witness: Mission Theology and Praxis in the 21st CenturyFrom EverandAfrica Bears Witness: Mission Theology and Praxis in the 21st CenturyHarvey KwiyaniNo ratings yet

- 8DCE978858-on InculturationDocument9 pages8DCE978858-on InculturationAGABA mosesNo ratings yet

- Proclaiming the Peacemaker: The Malaysian Church as an Agent of Reconciliation in a Multicultural SocietyFrom EverandProclaiming the Peacemaker: The Malaysian Church as an Agent of Reconciliation in a Multicultural SocietyNo ratings yet

- Releasing the Church from Its Cultural Captivity: A Rediscovery of the Doctrine of the TrinityFrom EverandReleasing the Church from Its Cultural Captivity: A Rediscovery of the Doctrine of the TrinityNo ratings yet

- Byang Kato: The Life and Legacy of Africa’s Pioneer Evangelical TheologianFrom EverandByang Kato: The Life and Legacy of Africa’s Pioneer Evangelical TheologianNo ratings yet

- Let It Shine!: The Emergence of African American Catholic WorshipFrom EverandLet It Shine!: The Emergence of African American Catholic WorshipNo ratings yet

- Alterity and the Evasion of Justice: Explorations of the "Other" in World ChristianityFrom EverandAlterity and the Evasion of Justice: Explorations of the "Other" in World ChristianityNo ratings yet

- Teoria - De.juegos JoaquinPerezDocument13 pagesTeoria - De.juegos JoaquinPerezjassonmujicaNo ratings yet

- McGowanHidden Behind WordsCommonweal9February2015Document2 pagesMcGowanHidden Behind WordsCommonweal9February2015jassonmujicaNo ratings yet

- On Christian Hope: What Makes It Distinctive and Credible?Document4 pagesOn Christian Hope: What Makes It Distinctive and Credible?jassonmujicaNo ratings yet

- Orobator Ethics Brewed in An African Pot JSCESummer 2011Document10 pagesOrobator Ethics Brewed in An African Pot JSCESummer 2011jassonmujicaNo ratings yet

- Endo SilenceDocument26 pagesEndo SilencejassonmujicaNo ratings yet

- Chestnut Hill Map Color 7-29-2015Document1 pageChestnut Hill Map Color 7-29-2015jassonmujicaNo ratings yet

- Endo's Silence Reading Comprehension Questions: Prologue Through Chapter 5Document3 pagesEndo's Silence Reading Comprehension Questions: Prologue Through Chapter 5jassonmujicaNo ratings yet

- 09 Economic Democracy KDDocument135 pages09 Economic Democracy KDjassonmujica100% (1)

- 08 Pod LocalDocument31 pages08 Pod LocaljassonmujicaNo ratings yet

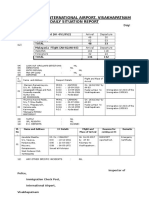

- Immigration, International Airport, Visakhapatnam Daily Situation ReportDocument2 pagesImmigration, International Airport, Visakhapatnam Daily Situation ReportSatyaNo ratings yet

- 1951-1953, Egypt: Nasser, The "Moslem Billy Graham"Document1 page1951-1953, Egypt: Nasser, The "Moslem Billy Graham"Amy BassNo ratings yet

- Edict of MilanDocument3 pagesEdict of MilanGiuseppe FrancoNo ratings yet

- Lohia in Karnataka - Appropriations of Lohia in KarnatakaDocument7 pagesLohia in Karnataka - Appropriations of Lohia in KarnatakaChandan GowdaNo ratings yet

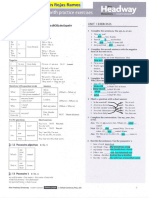

- TAREA de INGLES - Berenice Jazmin Rojas RamosDocument3 pagesTAREA de INGLES - Berenice Jazmin Rojas RamosBERENICE JAZMIN ROJAS RAMOSNo ratings yet

- Celebrating Differences PDFDocument2 pagesCelebrating Differences PDFapi-375168721No ratings yet

- HPPSC Junior Auditor Recruitment 2024 NotificationDocument12 pagesHPPSC Junior Auditor Recruitment 2024 NotificationHiamsjisbNo ratings yet

- AP GoPo DoI Declaration of Independence Reading and AnnotationDocument3 pagesAP GoPo DoI Declaration of Independence Reading and AnnotationRachel MillerNo ratings yet

- Bajpai - 2000 - Human Security - Concept and MeasurementDocument64 pagesBajpai - 2000 - Human Security - Concept and MeasurementhiramamohammedNo ratings yet

- IT IS WHAT IT IS - Change For HaitiDocument148 pagesIT IS WHAT IT IS - Change For HaitiGregster SapienceNo ratings yet

- The Filipino View of RizalDocument10 pagesThe Filipino View of RizalMaria Consolacion Catap100% (1)

- ICSE - History & Civics Sample Paper-1-solution-Class 10 Question PaperDocument9 pagesICSE - History & Civics Sample Paper-1-solution-Class 10 Question PaperFirdosh Khan100% (1)

- PU College - KarnatakaDocument27 pagesPU College - KarnatakaAyan SarkarNo ratings yet

- Angat Vs RepublicDocument2 pagesAngat Vs RepublicDianne ComonNo ratings yet

- Foreigners Act Amendment 2004Document2 pagesForeigners Act Amendment 2004Surender SinghNo ratings yet

- LIVING LIFE TO THE FULL: THE SPIRIT AND ECO-FEMINIST SPIRITUALITY - Susan RakoczyDocument13 pagesLIVING LIFE TO THE FULL: THE SPIRIT AND ECO-FEMINIST SPIRITUALITY - Susan RakoczymustardandwineNo ratings yet

- Gmail - One Hell of A DebateDocument27 pagesGmail - One Hell of A Debatenileshraut23No ratings yet

- Christophe Charle - Birth - of - The - IntellectualsDocument7 pagesChristophe Charle - Birth - of - The - Intellectualsjug2No ratings yet

- Master Thesis Hasar DemnatiDocument66 pagesMaster Thesis Hasar Demnatisarah shahNo ratings yet

- Social Stratification in Caribbean SocietyDocument5 pagesSocial Stratification in Caribbean SocietyNicole Maragh94% (16)

- UBC Poli 316 Class Notes: Global Indigenous PoliticsDocument80 pagesUBC Poli 316 Class Notes: Global Indigenous PoliticskmtannerNo ratings yet

- Funa v. COADocument51 pagesFuna v. COAk1685No ratings yet

- NOWSHEHRADocument406 pagesNOWSHEHRAjalal uddinNo ratings yet

- Steiner Waldorf Schools Part 3. The Problem of Racism: A Spiritual EliteDocument16 pagesSteiner Waldorf Schools Part 3. The Problem of Racism: A Spiritual ElitedocwavyNo ratings yet

- Jazz DiplomacyDocument226 pagesJazz DiplomacyJosephmusicNo ratings yet

- The Federations of Free Farmers CooperativesDocument3 pagesThe Federations of Free Farmers CooperativesJayson ChanNo ratings yet

- Educational Theory 2009 59, 4 Arts & Humanities Full TextDocument23 pagesEducational Theory 2009 59, 4 Arts & Humanities Full TextBianca DoyleNo ratings yet

- Making India A SuperpowerDocument16 pagesMaking India A SuperpowerharryNo ratings yet

- 3 Feb 19 GNLMDocument22 pages3 Feb 19 GNLMmayunadi100% (1)

- Local Governance PowerpointDocument18 pagesLocal Governance PowerpointJairus Socias100% (1)