Professional Documents

Culture Documents

"A Survey of Nominative Case Assignment by Adpositions" by Alan Libert

Uploaded by

Alan LibertCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

"A Survey of Nominative Case Assignment by Adpositions" by Alan Libert

Uploaded by

Alan LibertCopyright:

Available Formats

ALS98 PAPERS - Alan Libert

Australian

Linguistic

Society

1998

A Survey of Nominative Case Assignment by

Adpositions

Alan Libert, Department of Linguistics, University of

Newcastle, Callaghan,

lnarl@cc.newcastle.edu.au

Introduction

The Government-Binding rule of Case assignment by adpositions is "NP is

oblique if

governed by P" (Chomsky 1981:170), and this is consistent with

the fact that in some of

the best known languages, such as Latin and

German, objects (or complements) of

adpositions are marked for some case

other than the nominative. One may note the remark

by Beard (1995:240) that

"Ps do not occur without Case Marking on the nouns which they

accompany in

inflectional languages". However, one does sometimes find objects of

adpositions which are in the nominative. In this paper I shall present a

survey of the

circumstances in which this seemingly unusual phenomenon

occurs, as a first step to an

attempt to account for it.

One must bear in mind the distinction between abstract case and

morphological case (or

between case assignment and case realization). If

one accepts the GB notion of abstract

case, then it is certainly possible

that objects of adpositions which appear in the

nominative case are

assigned some abstract oblique case by a P, but that this abstract case

does not correspond to an overt oblique case (as happens to objects of

verbs in English). If

this is so, then it is not a question of nominative

case assignment by adpositions, but rather

of nominative case realization,

but the phenomenon is still of interest. However, one might

argue that some

examples of it present evidence against the notion of abstract case, or at

least that we need some principled way to determine whether an apparently

nominative (or

caseless) element has been assigned abstract nominative case

or an abstract oblique case.

Here I am not looking at situations such as that in English where nouns

lack an overt

accusative or oblique case, and hence appear to be in the

nominative after prepositions, but

rather at situations where an oblique

case form is available, but is not used. The rest of this

paper consists of

a presentation of the types of such situations which I have discovered,

and

a few preliminary remarks on how one might account for them.

Nominative Assignment "by Mistake"

Let us first consider what we might call case marking errors in

languages which, unlike

English, have morphological oblique cases on nouns.

In Classical Greek prepositions take

the genitive, dative, or accusative

cases. However, in later Greek there are a few examples

of prepositions

with nominative objects, as in the following example from a papyrus of the

Ptolomaic era with the preposition apo 'from', which usually takes

the genitive:

(1)

apo

from

'peliote:s [sic]

east.wind-NOM (cited in Mayser 1934:367)

This is very rare and is presumably a consequence of the breakdown of

the case system of

http://www.als.asn.au/proceedings/als1998/liber717.html[28/10/2016 3:57:31 PM]

FULL

PAPERS

ALS98 PAPERS - Alan Libert

Greek. In Modern Greek as well occasionally there may be

nominative objects of

prepositions, as illustrated by Thumb (1912:101),

although I am somewhat dubious about

whether they are such.

Portuguese is like English in that only pronouns show case, and indeed

only some pronouns

do; in Brazilian Portuguese prepositions have been

observed to occur with the nominative

of these pronouns, rather than the

expected non-nominative forms (Sebastian Drude,

personal communication

1998).

We also find "errors" of this sort in two ancient Semitic languages,

Akkadian and Ugaritic,

where prepositions "should" take genitive objects

but are found with nominative ones. The

loss of the genitive itself is not

so strange, but one may think it surprising that the

nominative, rather

than the accusative, so commonly replaces the genitive in its function of

marking prepositional objects. A point of interest about these languages,

and one which

adds to the apparent oddity of the just mentioned fact, is

that, unlike many case languages,

they have some nominative forms involving

discernible suffixes, so we cannot simply say

that the prepositional

objects have lost a case; rather, they clearly do have an overt

nominative

case marker. Such data may argue that in at least these instances we should

not

speak of abstract oblique cases being assigned and being realized as

nominatives (or

caseless forms). We may note that in at least most of the

languages mentioned the case

system was in decline, and case errors occur

in other structures as well.

In English there are case errors when pronouns occur as conjuncts; some

of these errors are

when the conjoined NPs are objects of prepositions.

Examples are given in (2)-(3).

(3) For both Steve and I, our marriage in 1979 was a second chance

(Evening Standard, 30 June 1992:2,

cited in Johannessen 1996:674)

(3) ... between you and I ...(Sobin 1997:319)

Given that this also happens outside of prepositional phrases, such

instances are perhaps to

be accounted for by some property of co-ordinators

rather than by some process particular

to prepositional objects.

Among the errors made by aphasics are those involving the substitution

of one case for

another. It can happen that the object of an adposition is

marked nominative rather than

with the required case. An example from

German is given below, where the article is

marked for nominative rather

than accusative.

(4)

fuer

for

ein

a-NOM

Mund

mouth

(Stark and Dressler 1990:419)

In further research I intend to compare the type and frequency of these

errors with the

errors in normal language just described in order to see

whether there are any common

features.

Nominative Assignment in "Standard" Languages

We now turn to nominative objects of adpositions which might not be

considered the result

of errors, i.e. deviations from a certain normal

state, although this is of course an arbitrary

judgement.

I know of no language in which all objects of adpositions are nominative

(again,

considering only languages which have an overt case system).

However, there are

http://www.als.asn.au/proceedings/als1998/liber717.html[28/10/2016 3:57:31 PM]

ALS98 PAPERS - Alan Libert

languages in which some such objects are marked

nominative. We shall first look at

languages where some adpositions have

nominative objects (and other adpositions have

objects in another case),

i.e. where the choice of case seems to be a lexical matter, and then

languages where it depends on some feature of the object or on some

semantic factor.

In many languages adpositions differ in which case they take, for

example in Latin some

prepositions take the accusative while others take

the ablative (and some take either,

depending on the meaning). At least a

few languages have the same sort of differences

among adpositions, with one

of the possibilities being the nominative case. Albanian has

some

prepositions which require accusative objects, and some which require

ablative

objects, but also two prepositions which take nominative objects,

te (or tek) 'at, to' and nga

'from' (I thank Wayles

Brown for pointing this out to me). Similarly, in Spanish segun

'according to' takes the nominative, unlike most prepositions (thanks to

James L.

Fidelholtz and Matthew L. Juge for this information).

In ergative languages the basic function of the nominative, marking

subjects, is covered

partly by the ergative and partly by the absolutive;

prepositional objects bearing these

cases could be the equivalent in

ergative languages of the nominative objects under

discussion, and might be

seen as equally unusual, as perhaps shown by the following quote

from

Haspelmath (1993:22) on the Lezgian postposition patal 'for': "This

postposition ...

inexplicably takes an Absolutive argument." Several other

postpositions in this language

also have absolutive objects. My intuition

is that ergative objects of adpositions would

be more unusual than

absolutive objects, but note that Mel'chuk (1988:208) uses

nominative to refer to the absolutive, since it is "the most

unmarked case".

In some languages there is a split in case marking, depending on what

type of constituent is

the head of the NP. In at least some Turkic

languages several postpositions take the

nominative of nouns, but the

genitive of some pronouns. For example, in Turkish the

postpositions

gibi 'like', ile 'with', kadar 'as much as', and

ichin 'for' act in this way; other

Turkish postpositions take

objects marked with one of the following cases: nominative

(only), dative

or ablative. In (5)-(6) are sentences illustrating the behaviour of

ile:

(5)

(6)

kim-in

ile

gittiniz?

who-GEN

with

you-went

'with whom did you go?' (Lewis 1967:86)

vapur

ile

gittiniz

boat-NOM

with

you-went

'you went by boat' (ibid.)

A few remarks are in order here. First, what I am calling the nominative

in Turkish has a

significant difference from the nominative cases of

languages such as Latin and Greek:

this case is also borne by direct

objects if they are not "definite" (v. Lewis 1967:35-6 for

details), i.e.

it covers some of the territory of the accusative of many other case

languages.

Lewis calls it the absolute rather than the nominative. One may

wonder whether this

difference has any connection with the facts just

described, and whether there is a

language with a more typical nominative

where these same facts hold.

Second, two of these postpositions, ile and ichin, also

turn up as suffixes, namely -yle and

chin (and variations),

so it is not entirely clear whether we are in fact talking about

postpositions (although they are affixed to a genitive stem rather than a

nominative stem

when the relevant pronouns are involved, with the

exceptions to be mentioned

immediately below). Finally, the pronouns which

generally appear in the genitive before

adpositions sometimes (namely

"colloquially" (Lewis 1967:85)) bear nominative case:

Lewis (1967:86) says,

"This is particularly frequent with kim; instead of kiminle,

kimin

ichin, and kimin gibi 'with whom?', 'for whom?', 'like

whom?', one hears kimle, kim ichin,

and kim gibi, the

last being a more respectable solecism than the first two". This may be

http://www.als.asn.au/proceedings/als1998/liber717.html[28/10/2016 3:57:31 PM]

ALS98 PAPERS - Alan Libert

seen as the same kind of "error" as those in Greek and other languages

described earlier.

The pronouns which are (generally) genitive here are ben 'I',

sen 'you (singular/informal)', o

'he, she, it, that',

biz 'we', siz 'you (plural/formal)', bu 'this',

shu 'that', and kim 'who?'. A fact

complicating any attempt

to account for this phenomenon is that when these pronouns take

the plural

ending -ler/-lar they are nominative, not genitive, e.g. onlar

gibi 'like them'

(Lewis ibid.).

In some languages there is a split with respect to the case taken by an

adposition based not

on the syntactic category of the object, but on

semantics: the choice between the

nominative and some other case depends on

the meaning to be expressed; this is similar to

the situation in Latin

where several prepositions can take accusative or ablative objects.

This

appears to happen with two postpositions in the Turkic language Bashkir:

saqlI

means 'like(= the size of)' with the nominative, but 'up to,

until, till' with the dative; tiklem

has the latter meaning with the

dative, and means 'the size of' with the nominative (glosses

from Poppe

1964:41).

We find something similar in several Indo-European languages. For

example, Russian has

two prepositions, za and v, which general

ly take oblique cases, but which apparently take

the nominative in certain

circumstances, although they could perhaps be analyzed as

something other

than prepositions in those circumstances (I thank Daniel E. Collins and

Keith Goeringer for drawing my attention to these facts).

Towards an Account for Nominative Adpositional Objects

One may say first that nominative marking of objects of adpositions is

not that unusual a

phenomenon; the feeling that it is odd may be a result

of the fact that it is quite uncommon

in the case languages most familiar

to traditional linguistics. I know of no a priori

theoretical reason why

such objects should not bear nominative case; there is presumably

not the

potential for confusion with sentence subjects as there would be if verbal

objects in

a free word order language were marked nominative rather than

accusative.

When a language has different Ps taking objects in different cases, one

of which is the

nominative, the account for this would presumably be the

same as the account for why

some verbs in German and Latin take objects in

different cases than the accusative: it is a

lexical property of those

verbs that they assign dative, or some other case. Therefore it is

marked

in the lexical entry of Albanian nga 'from' that it assigns

nominative. Chomsky's

rule for case assignment for Ps would have to be

modified in any event to handle

languages where more than one oblique case

can be assigned by Ps; one might suggest

something like "P assigns

accusative unless otherwise specified by its lexical entry". I see

no

principled reason to assume that nga assigns an abstract oblique

case, which is not

realized as such, given the fact that other Ps in the

language assign oblique cases which do

show up as oblique morphological

cases.

Splits in case marking based on the nature of the object are somewhat

more difficult to

account for, but note that again this is not a problem

unique to nominative adpositional

objects. An account for the Turkish-type

split in terms of lexical properties of individual

elements is possible,

though unattractive. Recall, however, that the split does not occur

with

all postpositions (and indeed not all postpositions taking the nominative,

although

there are only two of these which do not exhibit the split, one of

which usually has an

infinitive as an object, and the other one being

"obsolete except in archaizing poetry"

(Lewis 1967:85)). Thus, in any case,

there will have to be reference to lexical properties of

http://www.als.asn.au/proceedings/als1998/liber717.html[28/10/2016 3:57:31 PM]

ALS98 PAPERS - Alan Libert

particular

postpositions. The problem is with those pronouns which are involved in the

split: if some of them are not to be lexically specified as to which case

they bear in certain

contexts, a more general mechanism will have to be

found. At the moment I know of no

such solution; I am not convinced that

the discussion in Kornfilt (1984:61, 225-7) will

account for all the

details.

However, one may note that there are other splits between pronouns and

nouns, and even

between different kinds of pronouns, involving either

abstract or morphological case.

Examples of these include the difference

between English nouns and pronouns, or between

who and what,

the former having distinct nominative and accusative forms, the latter not.

(It is interesting that the Turkish equivalents display a difference with

respect to case

marking before the postpositions under discussion,

kim 'who' being genitive while ne

'what' is nominative.) If

such splits can be attributed to other properties of these elements,

the

latter might be invoked in an explanation of the complicated facts of

Turkic languages

(this idea is due to Anne Robotham). That is, some

properties of pronouns, or of some

pronouns, may make them more or less

likely to be assigned oblique case, or more or less

likely to lose

morphological case.

A similar kind of account can perhaps be extended to the case "errors" due to language

change or disordered language. One might think that when adpositional objects lose their

originalcase marking, due to the decline

of the case system of a language, they are marked

for some other case,

usually not nominative. However, perhaps some kinds of elements are

more

vulnerable to nominative marking than others, in normal and/or aphasic

language;

although they too would usually be marked with the accusative or

another non-nominative

case, perhaps a certain combination of factors makes

it possible for them to be nominative.

It would therefore be worthwhile to

collect and analyze a large number of such "errors" to

determine whether

they are more likely to occur in some circumstances than others, e.g.

are

objects of certain prepositions more likely to bear nominative than others,

or are

certain types of objects more susceptible to such unusual case

marking than others?

As has been shown, although it is not a very common phenomenon, objects

of adpositions

can bear nominative case, perhaps more often than supposed.

A detailed analysis of the

situations where it happens, and of the

constituents to which it tends to occur, may allow

us to explain both why

it occurs at all, and why it is relatively rare.

Note

I thank George Horn, Christo Moskovsky, Peter Peterson, and Anne

Robotham for useful

discussion.

References

Beard, R. 1995. Lexeme-morpheme base morphology. Albany,

NY:State University

of New York Press.

Chomsky, N. 1981. Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht:

Foris

Haspelmath, M. 1993. A grammar of Lezgian. Berlin: Mouton de

Gruyter.

Johannessen, J.B. 1996. Partial agreement and coordination.

Linguistic Inquiry 27.

661-676.

Kornfilt, J. 1984. Case marking, agreement, and empty categories in

Turkish. PhD

thesis, Harvard University.

http://www.als.asn.au/proceedings/als1998/liber717.html[28/10/2016 3:57:31 PM]

ALS98 PAPERS - Alan Libert

Lewis, G.L. 1967. Turkish grammar. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Mayser, E. 1934. Grammatik des griechischen Papryri aus der

Ptolomaeerzeit.

(Band II 2) Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Mel'chuk, I.A. 1988. Dependency Syntax. Albany, NY:State

University of New York

Press.

Poppe, N. 1964. Bashkir manual. (Uralic and Altaic Series, 36)

Bloomington:

Indiana University.

Sobin, N. 1997. Agreement, default rules, and grammatical viruses.

Linguistic

Inquiry 28. 318-343.

Stark, J.A. and Dressler, W.U. 1990. Agrammatism in German: two case

studies. In

Menn, L. and Obler, L.K. (eds), Agrammatic aphasia.

Philadephia: John Benjamins.

2281-441.

Thumb, A. 1912. Handbook of the modern Greek vernacular.

Edinburgh: T. & T.

Clark.

http://www.als.asn.au/proceedings/als1998/liber717.html[28/10/2016 3:57:31 PM]

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- EnglishDocument331 pagesEnglishAditya MishraNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- HW5e PreIntermediate International WordlistDocument19 pagesHW5e PreIntermediate International Wordlisttoth100% (1)

- English For DiplomatsDocument17 pagesEnglish For DiplomatsToanNguyen100% (3)

- Latin Vocabulary GuideDocument48 pagesLatin Vocabulary GuideawetiaNo ratings yet

- Outline For Informative SpeechDocument62 pagesOutline For Informative SpeechJames G. Villaflor IINo ratings yet

- Grammar AnalysisDocument14 pagesGrammar AnalysisIntan Nurbaizurra Mohd RosmiNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Guide To English UsageDocument0 pagesCambridge Guide To English UsageCristina TomaNo ratings yet

- Scheme of Work - English Stage 9: Cambridge Lower SecondaryDocument44 pagesScheme of Work - English Stage 9: Cambridge Lower SecondaryInna Glushkova100% (1)

- Verb-particle combinations in Present-Day EnglishDocument28 pagesVerb-particle combinations in Present-Day EnglishIsrael BenavidesNo ratings yet

- Valyrian Swadesh PDFDocument4 pagesValyrian Swadesh PDFFrancisco AdaildoNo ratings yet

- Transitivity - Form, Meaning, Acquisition, and ProcessingDocument321 pagesTransitivity - Form, Meaning, Acquisition, and ProcessingBomber KillerNo ratings yet

- Describing My House Podcast for Elementary StudentsDocument1 pageDescribing My House Podcast for Elementary StudentsCristina TirsinaNo ratings yet

- STIP Jakarta English Course Syllabus and Lesson PlansDocument18 pagesSTIP Jakarta English Course Syllabus and Lesson PlansSariNo ratings yet

- A - Use Simple FormulaeDocument2 pagesA - Use Simple FormulaeAlan LibertNo ratings yet

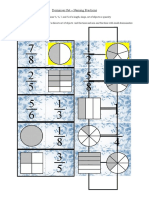

- FDP - Naming FractionsDocument2 pagesFDP - Naming FractionsAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- AS - Add - Subtract 3 Digit Numbers and 100sDocument2 pagesAS - Add - Subtract 3 Digit Numbers and 100sAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Amy's Omelette House by Jenn Giesler - IssuuDocument3 pagesAmy's Omelette House by Jenn Giesler - IssuuAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- AS - Add - Subtract 3 Digit Numbers and 1sDocument2 pagesAS - Add - Subtract 3 Digit Numbers and 1sAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Toponyms and Anthroponyms in Recipes from NC and SCDocument2 pagesToponyms and Anthroponyms in Recipes from NC and SCAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- AS - Add - Subtract 2 Digit Numbers and 1sDocument2 pagesAS - Add - Subtract 2 Digit Numbers and 1sAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- AS - Add - Subtract 2 Digit Numbers and 10sDocument2 pagesAS - Add - Subtract 2 Digit Numbers and 10sAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Black Sea PaperDocument6 pagesBlack Sea PaperAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Add and subtract 3 digit numbers with tens and onesDocument2 pagesAdd and subtract 3 digit numbers with tens and onesAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- KHS Talk HandoutDocument4 pagesKHS Talk HandoutAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- AS - Add - Subtract 1 and 2 Digit Numbers (To 20)Document2 pagesAS - Add - Subtract 1 and 2 Digit Numbers (To 20)Alan LibertNo ratings yet

- Words For Berries in Artificial Languages Alan Reed LIBERTDocument5 pagesWords For Berries in Artificial Languages Alan Reed LIBERTAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Sydney Language Festival Program Guide PDFDocument1 pageSydney Language Festival Program Guide PDFAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Actes Du 6e Colloque Franco Finlandais de Linguistique Contrastive PDFDocument4 pagesActes Du 6e Colloque Franco Finlandais de Linguistique Contrastive PDFAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- User Manual for Washing MachinesDocument24 pagesUser Manual for Washing MachinesAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Sydney Language Festival Program GuideDocument1 pageSydney Language Festival Program GuideAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Words For Berries in Artificial Languages Alan Reed LIBERTDocument5 pagesWords For Berries in Artificial Languages Alan Reed LIBERTAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Skeptical Adversaria 2010 No. 4Document12 pagesSkeptical Adversaria 2010 No. 4Alan LibertNo ratings yet

- On Framework For Classifying Case Marking Errors in Disordered SpeechDocument3 pagesOn Framework For Classifying Case Marking Errors in Disordered SpeechAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- How To Make Bagpipes Out of A Garbage Bag and RecordersDocument14 pagesHow To Make Bagpipes Out of A Garbage Bag and RecordersAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Semantic and Pragmatic Factors in The Re PDFDocument18 pagesSemantic and Pragmatic Factors in The Re PDFAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Akkadian Lang FestDocument4 pagesAkkadian Lang FestAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- The Skeptical Intelligencer 16.4Document23 pagesThe Skeptical Intelligencer 16.4Alan LibertNo ratings yet

- Transplanting Pragmatic Orientations Within Conlang TranslationsDocument12 pagesTransplanting Pragmatic Orientations Within Conlang TranslationsAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Esperanto (S) en Perspektivo? Croatian Esperantists On The International Auxiliary Language EsperantoDocument20 pagesEsperanto (S) en Perspektivo? Croatian Esperantists On The International Auxiliary Language EsperantoAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Newsletter 9Document1 pageNewsletter 9Alan LibertNo ratings yet

- Akkadian Lang FestDocument4 pagesAkkadian Lang FestAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Handwriting Instruction - P.E.IDocument21 pagesGuidelines For Handwriting Instruction - P.E.IJune Kasperski WildNo ratings yet

- Writing Effective Learning ObjectivesDocument2 pagesWriting Effective Learning ObjectivesAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- On Some Aspects of JW in Middle EgyptianDocument11 pagesOn Some Aspects of JW in Middle EgyptianAngelika ErhardtNo ratings yet

- English Lecture SheetsDocument63 pagesEnglish Lecture Sheetstipu1sultan_1100% (2)

- English GrammerDocument633 pagesEnglish GrammeratniwowNo ratings yet

- TocDocument4 pagesTocronald_edinsonNo ratings yet

- Close-Up A1+ TOCDocument2 pagesClose-Up A1+ TOCJuan Perez100% (1)

- Kumpulan Soal Bahasa InggrisDocument16 pagesKumpulan Soal Bahasa InggrisBayu PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Achievers 7 - WordlistDocument42 pagesAchievers 7 - WordlistNguyễn Minh ThưNo ratings yet

- Khady Tamba - The Argument Structure of Passive and Antipassive in PaloorDocument12 pagesKhady Tamba - The Argument Structure of Passive and Antipassive in PaloorMaxwell MirandaNo ratings yet

- TET English Mini Study GuideDocument62 pagesTET English Mini Study GuideuvaarajNo ratings yet

- Degrees of Comparison and Adjective Clause Degrees of Comparison and Adjective ClauseDocument38 pagesDegrees of Comparison and Adjective Clause Degrees of Comparison and Adjective ClausenaiunieNo ratings yet

- GRAMMARREVIEWDocument31 pagesGRAMMARREVIEWpaulinaveraNo ratings yet

- John Eastwood - AnswersDocument40 pagesJohn Eastwood - AnswersSyed Adeel AliNo ratings yet

- Simple guide to tenses, clauses, sentence structures and language usageDocument38 pagesSimple guide to tenses, clauses, sentence structures and language usageRohit D HNo ratings yet

- Unit4Document21 pagesUnit4distinnguyenrbNo ratings yet

- 4.1-The Writing ProcessDocument81 pages4.1-The Writing ProcessJohn Paul LiwaliwNo ratings yet

- A Descriptive Study On Noun Phrases in English and VietnameseDocument35 pagesA Descriptive Study On Noun Phrases in English and VietnameseThùy Linh HoàngNo ratings yet

- 3-Handbook English For NurseDocument39 pages3-Handbook English For NurseS4bun GamingNo ratings yet