Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tranexa Topical IV

Uploaded by

Siva SankarCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tranexa Topical IV

Uploaded by

Siva SankarCopyright:

Available Formats

A Retrospective Analysis of Blood Loss With Combined Topical and

Intravenous Tranexamic Acid After Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery

Ryan Mahaffey, MD,* Louie Wang, MD, FRCPC, MSc,* Andrew Hamilton, MD, FRCSC, Rachel Phelan, MSc,*

and Ramiro Arellano, MD, FRCPC, MSc*

Objective: Intravenous antifibrinolytics are the gold standard for blood conservation during cardiac surgery. Recent

evidence suggests that topical tranexamic acid administration also is effective, although the efficacy of combined

topical and intravenous administration has never been reported. Combined administration may offer superior hemostasis while decreasing side effects. The current study explores the use of combined topical and intravenous tranexamic

acid as a blood conservation strategy in cardiac surgery.

Design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: A single-center, academic, tertiary care hospital.

Participants: One hundred sixty elective coronary artery

bypass graft patients.

Intervention: A practice change allowed a retrospective

comparison of postoperative chest tube drainage in patients

with intravenous or combined (intravenous and topical)

tranexamic acid.

Measurements and Main Results: Chest tube drainage

was decreased in the combined group at 3 (164.8 102.2

v 242.7 148.9 mL, p < 0.001), 6 (265.6 163.7 v 358.8

247.2 mL, p 0.006), and 12 hours (374.3 217.1 v 498.5

336.6 mL, p 0.006) postoperatively compared with the

intravenous group. The tranexamic acid dose was higher

in the combined group (5.1 1.1 v 4.1 1.3 g, p < 0.001),

but less was administered intravenously (3.1 1.1 v 4.1

1.3 g, p < 0.001). No differences were observed in adverse

events.

Conclusions: This study suggested that combined

tranexamic acid administration may be superior for blood

conservation, but fully powered randomized controlled trials will be required to confirm these findings and determine

the safety advantage and clinical relevance of adding topical

tranexamic acid to existing blood conservation strategies.

2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

The use of combined topical and IV antifibrinolytic administration has not been well investigated. Combined topical and

IV aprotinin inhibits local fibrinolysis and reduces blood loss

by 33% after CABG surgery compared with IV administration.4

To the authors knowledge, there are no reports that examine

combined topical and IV TXA compared with IV TXA. Because TXA has a different mechanism of action, it is difficult to

know whether it would act similar to aprotinin. (TXA is a

lysine analog, and aprotinin is a serine protease inhibitor.) The

primary purpose of the current analysis was to determine

whether topical TXA applied directly to the pericardium in

combination with IV TXA was associated with reduced postoperative blood loss compared with IV administration alone.

Based on previous investigations,4,6 the authors hypothesized

that the addition of topical TXA to IV TXA would result in less

chest tube drainage after CABG surgery.

ESPITE ADVANCES in technique and postoperative

care, blood loss remains a major problem in cardiac surgery.1 Allogeneic blood transfusions during coronary artery

bypass graft (CABG) surgery have been associated with increased morbidity and mortality and resulted in recommendations from the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists and

the Society of Thoracic Surgeons to administer antifibrinolytics

as part of routine blood conservation strategies in cardiac

surgery for patients at high risk for bleeding.2

Cardiac surgery patients have increased pericardial activation of clotting and fibrinolytic systems.3 The pericardium is an

area of intense fibrinolytic activity during cardiac surgery,

which exceeds that in the systemic circulation.3,4 Antifibrinolytic agents inhibit fibrinolysis and are used routinely in cardiac

and noncardiac surgery. A number of studies have shown that

both intravenous (IV) tranexamic acid (TXA)2,5 and topically

applied6-10 TXA are effective in reducing blood loss after

cardiac surgery. A recent meta-analysis determined that topical

TXA decreased blood loss by 250 mL (and 1.6 U of transfused

packed red blood cells [PRBCs]) per patient during cardiac

surgery compared with placebo.6 To the authors knowledge,

only 1 investigation measured the systemic levels of topically

applied TXA during cardiac surgery and reported no systemic

absorption.10 This implied that topical TXA may act via local

fibrinolysis inhibition rather than through systemic mechanisms.

From the Departments of *Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine and Surgery, Queens University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

Address reprint requests to Louie Wang, MD, FRCPC, MSc, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative Medicine, Queens University, Victory 2, Kingston General Hospital, 76 Stuart Street, Kingston,

Ontario, Canada K7L 2V7. E-mail: ryanmahaffey@gmail.com

2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1053-0770/2701-0001$36.00/0

http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2012.08.004

18

KEY WORDS: tranexamic acid, blood loss, postoperative,

drug administration route, cardiac surgery, topical

administration

METHODS

After institutional ethics board approval, charts of 160 patients who

underwent elective, primary CABG surgery were reviewed. All surgery

was performed by a single highly experienced surgeon who, as of

February 2010, began administering topical pericardial TXA (Cyklokapron; Sandoz, Boucherville, Canada) in addition to standard IV

delivery.

Based on the literature5,8-10 and institutional data, the authors estimated that patients with IV TXA would have 500 mL of chest tube

drainage 12 hours postoperatively, and this would be reduced to 400

mL with the addition of topical TXA. The sample size was calculated

to detect a 20% difference in chest tube drainage (p 0.05, 0.8,

n 64) and was increased conservatively to 80 per group. Exclusion

criteria were bleeding disorder history, previous cardiac surgery, valve

surgery, and emergency or off-pump cardiac surgery. Data were collected from the first 80 eligible patients (March 1, 2010-October 30,

2010) who received combined topical IV TXA (Top IV group).

These were compared with the charts of the first 80 eligible patients

who received IV TXA (IV group) from the period preceding the change

in practice (January 1, 2009-September 30, 2009).

Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia, Vol 27, No 1 (February), 2013: pp 18-22

CABG SURGERY WITH TRANEXAMIC ACID

19

Table 1. Adverse Events

Condition

Cardiac death

Cardiogenic shock

Mortality

Myocardial infarction

Persistent atrial fibrillation

Renal failure

Respiratory failure

Stroke

Reoperation

Postoperative seizure

Definition

Death caused primarily by congestive heart failure, cardiogenic shock, myocardial infarction, or

right ventricular failure

Inotropic support for more than 12 h or intra-aortic balloon pump insertion required to maintain

cardiac function

Patient death within 30 postoperative days

Heart attack confirmed by electrocardiogram (new Q waves or ST-segment or T-wave changes) or

elevation in cardiac troponin

New-onset electrocardiogram-documented abnormal heart rhythm present at hospital discharge

Kidney dysfunction requiring dialysis

Prolonged intubation (48 h) or the need for reintubation to maintain respiratory function

Postoperative stroke diagnosed by a neurologist and a computed tomography scan

Taken back to the operating room for surgical re-exploration for ongoing bleeding in the

postoperative period

The observation of abnormal motor movements characteristic of epileptic convulsions in the

absence of other identifiable causes

The surgical technique was standardized between the 2 groups.

Blood transfusions were administered to maintain a hemoglobin level

of 7.5 g/dL or at the discretion of the attending physician in the

setting of ongoing hemorrhage or refractory hypovolemia. The total IV

dose of TXA ranged from 2 to 10 g consisting of a bolus continuous

infusion. The different dosing protocols reflected the varied training of

the cardiac anesthesiologist involved in the case as well as individual

patient factors. IV heparin was administered to achieve a minimum

activated coagulation time of 480 seconds before cardiopulmonary

bypass, and IV protamine was administered at the end of the case to

ensure the return of the activated coagulation time to within 10% of

baseline. Subjects in both groups received IV TXA before sternal

incision. The Top IV group also received 2 g of TXA in 0.9% saline

(volume of 120 mL) topically applied to the pericardium. The topical

TXA dose was determined after reviewing the literature in which the

examined range was between 1 and 2.5 g diluted in 100 to 250 mL of

saline.7-10 The TXA solution was poured into the pericardium until the

heart was covered, and the remainder then was poured into the mediastinal chest tube before sternal closure. The mediastinal and pleural

tubes were clamped for 10 minutes before suctioning at 20 cmH2O

using a Pleur-evac system (Teleflex, Markham, Canada). No topical

solution was administered to the IV group. Chest tube drainage was

recorded hourly until chest tube removal.

The primary outcome measure was the cumulative chest tube

drainage 12 hours postoperatively. All chest tubes are traditionally

in place at 12 hours postoperatively although they often are removed

before 24 hours. The secondary outcome measures were chest tube

drainage 3 and 6 hours postoperatively, blood products transfused

(ie, units of PRBCs, platelets, and fresh frozen plasma [FFP]), and

adverse events (ie, all-cause death, cardiac death, myocardial infarction, stroke, new-onset atrial fibrillation, renal failure, cardiogenic shock, the need for reoperation, and seizures) until discharge

(Table 1). Other collected information included demographics; past

medical history; medications; surgical details (number of grafts);

doses of topical and IV TXA; laboratory values (ie, hemoglobin,

platelet count, international normalized ratio, partial thromboplastin

time, and creatinine) preoperatively, immediately postoperatively,

and postoperative day 1; hematocrit before cardiopulmonary bypass

(CPB) and immediately after; the duration of surgery, CPB, and

aortic cross-clamp; and the time until chest tube removal. Continuous data are presented as mean standard deviation and categoric

variables as number and percentage. Data were analyzed using SPSS

for Windows 19.0 statistical software (IBM Corporation, Somers,

NY). Continuous data were compared using the Student t test.

Categoric data were compared using the Pearson chi-square test or

the Fisher exact test when appropriate. The differences in postoperative bleeding at 3, 6, and 12 hours were examined using MannWhitney rank sum nonparametric tests. Multivariate analyses were

used to evaluate the impact of treatment (IV TXA v combined

administration), pump time, age, sex, and prepump hematocrit

counts on transfusions and 12-hour cumulative chest tube drainage.

RESULTS

Groups were similar with respect to demographics, cardiac

risk factors, preoperative hematologic data, and medications

that could affect coagulation (Table 2). Intraoperative variables

also were similar (Table 3). Patients receiving combined topical

and IV TXA had less chest tube drainage than those in the IV

group at 3 (164.8 102.2 v 242.7 148.9 mL), 6 (265.6

163.7 v 358.8 247.2 mL), and 12 hours (374.3 217.1 v

498.5 336.6 mL) postoperatively (Fig 1).

Patients in the Top IV group received less IV TXA but

received an additional 2 g topically (Table 3). Although

fewer patients in the Top IV group required PRBCs (29 v

33, p 0.52), FFP (11 v. 15, p 0.39), and/or platelets (6

v 9, p 0.42), the differences were not statistically significant. There also was no difference in the quantity of

PRBCs, FFP, or platelets transfused (Table 4). There were

no detectable differences in postoperative laboratory values

or adverse events (Tables 5 and 6). At 12 hours, all patients

still had chest tubes in place, but 73% were removed by 24

hours. Multivariate analyses revealed that study group was

the only predictor of 12-hour chest tube drainage (p 0.01)

(model R2 0.073). Age (p 0.01) and pre-CPB hematocrit

(p 0.001) were the only predictors of transfusion (model

R2 0.483).

DISCUSSION

The main observation of the current investigation was that

postoperative chest tube drainage was reduced by 32% at 3

hours, 26% at 6 hours, and 25% 12 hours after CABG surgery

when patients received combined topical and IV TXA com-

20

MAHAFFEY ET AL

Table 2. Patient Demographics and Cardiac Risk Factors

Parameter (Mean SD Unless

Stated)

Age (y)

Sex (no. of males/females)

Height (cm)

Weight (kg)

Left ventricular grade (I-IV)*

Hemoglobin (g/L)

Platelets (109/L)

INR

PTT3

Creatinine (mol/L)

Peripheral vascular disease

(%)

Dialysis (%)

Liver disease (%)

Cerebrovascular disease

(%)

Previous myocardial

infarction (%)

Congestive heart failure (%)

Clopidogrel (%)

Heparin (%)

LMWH

IV (n 80)

Top IV

(n 80)

p

Value

64.3 10.2

66/14

171.2 8.5

87.0 18.9

1.63 0.79

134.1 17.4

228.8 67.0

1.1 0.1

39.0 22.1

105.2 99.9

64.4 10.8

61/19

170.7 8.8

86.7 16.1

1.49 0.66

132.2 14.6

219.7 66.0

1.1 0.1

34.0 11.0

89.2 26.0

0.93

0.33

0.70

0.93

0.25

0.46

0.40

0.07

0.17

15 (18.8)

1 (1.3)

1 (1.3)

13 (16.3)

0

0

0.68

0.32

0.32

10 (12.5)

11 (13.8)

0.81

48 (60)

9 (11.3)

16 (20)

21 (26.3)

0

49 (61.3)

7 (8.8)

20 (25)

23 (28.8)

0

0.87

0.60

0.45

0.72

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; INR, international normalized ratio (measure of time to clot); PTT, partial thromboplastin time

(measure of clotting ability); LMWH, lowmolecular-weight heparin.

*Graded on a scale of I-IV based on left ventriculogram. Grade I left

ventricular function: ejection fraction of 50%. Grade II left ventricular function: ejection fraction of 35% to 50%. Grade III left ventricular

function: ejection fraction of 20% to 35%. Grade IV left ventricular

function: ejection fraction of 20%.

pared with only IV TXA. The results of this investigation

advance the current state of knowledge because it was the first

published study comparing combined topical and IV TXA with

only IV TXA. De Bonis et al10 were the first to investigate

topical TXA in cardiac surgery and observed a reduction in

chest tube drainage after 1 g of topical TXA when compared

with placebo. Three other randomized controlled trials compared topical TXA with placebo during cardiac surgery, and all

showed a significant decrease in postoperative chest tube drainage.7-9 One study also showed a decrease in PRBC transfusions

Table 3. Intraoperative Variables

Parameters (Mean SD)

IV (n 80)

Number of grafts (no.)

Use of internal

mammary artery

(no. used)

Cross-clamp (min)

CPB (min)

Surgical time (min)

TXA dose (IV, g)

TXA dose (topical, g)

Total TXA (g)

Pre-CPB hematocrit

Post-CPB hematocrit

3.1 0.8

1.2 0.5

38.4 11.6

49.2 17.1

183.4 30.6

4.1 1.3

0

4.1 1.3

0.40 0.05

0.29 0.04

Top IV (n 80)

3.3 0.8

1.2 0.4

38.2 10.0

47.9 11.5

182.7 28.4

3.1 1.1

2.0 0.0

5.1 1.1

0.41 0.04

0.30 0.03

p Value

0.30

0.36

0.91

0.59

0.88

0. 001

0.001

0.45

0.10

Fig 1. Cumulative chest tube drainage after CABG surgery comparing IV TXA (n 80) with combined IV and topical administration

(n 80) (mean standard deviation).

and the rate of surgical re-exploration.9 None of the previous

studies included IV TXA in either group and were only comparing topical TXA with placebo. As mentioned previously, a

recent meta-analysis showed a 250-mL decrease in chest tube

drainage 24 hours after surgery with the application of topical

TXA, and this was associated with a 1.6-U reduction of PRBCs

per patient when compared with placebo.6 Although the source of

bleeding postoperatively most likely included sources both within

and outside the pericardium (most notably the harvested internal

mammary site),11 the fact that topical TXA was effective in

previous studies suggested there was ongoing bleeding in the

pericardium amenable to topical antifibrinolytic therapy. Given the

fact that fibrinolysis in the pericardium exceeds that in the systemic circulation during cardiac surgery,3,4 it is not surprising that

TXA applied topically to the pericardium was effective in reducing chest tube drainage. The authors suspected that topical TXA

reduced chest tube drainage by suppressing local fibrinolytic activity in the pericardium because topical TXA has been shown to

have no systemic absorption from the pericardial sac.10

Table 4. Blood Products Administered

Delivery Time and Product

Used (Mean SD)

Intraoperative

PRBC (U)

FFP (U)

Platelets (dose)

Postoperative: 24 h

PRBC (U)

FFP (U)

Platelets (dose)

Postoperative: 24 h

PRBC (U)

FFP (U)

Platelets (dose)

Total

PRBC (U)

FFP (U)

Platelets (dose)

IV (n 80)

Top IV (n 80)

p Value

0.3 0.6

0

0

0.3 0.7

0

0

0.71

0.6 1.2

0.6 1.5

0.2 0.5

0.3 0.9

0.3 1.1

0.1 0.4

0.22

0.25

0.37

0.2 0.6

0

0

0.1 0.3

0.03 0.20

0

0.14

0.32

1.0 1.7

0.6 1.5

0.2 0.5

0.8 1.3

0.4 1.1

0.1 0.4

0.24

0.31

0.37

CABG SURGERY WITH TRANEXAMIC ACID

21

Although the authors observed reduced chest tube drainage, they were unable to detect a significant reduction in the

transfusion of blood products. A number of factors may have

contributed to this. First and most important was that this

study was not powered to detect differences in exposure to

allogeneic blood products. Second, the authors only included

low-risk CABG patients, which also may have impacted the

results. If high-risk patients, such as those undergoing valve

replacement/repair or repeat sternotomy, had been included,

the transfusion rates would have been higher and more likely

to reveal significant differences between groups. Third, although chest tube drainage is a risk factor for the transfusion

of blood products, previous investigations have documented

that the predictors of chest tube drainage are not necessarily

the same as those for transfusion.12 A sample size analysis

based on the results from this study suggested that in excess

of 800 patients would be required to show a difference in

PRBC transfusion.

The results of the current study did not show any differences

in major adverse events, but this study was not adequately

powered to detect differences in such rare events. Given recent

reports of increased risks for seizures using high-dose IV TXA

in cardiac surgery,13 topical administration, with or without IV,

may provide comparable antifibrinolytic activity with an improved safety profile. Although there was some concern that

topical TXA might increase the risk of pericardial tamponade

and/or clotting of the chest tubes, no evidence of such problems

was observed.

Retrospective investigations are subject to bias and limitations. Major limitations of the current investigation were that

systemic TXA levels were not measured and the TXA dosing

Table 5. Postoperative Hematology Measures

Measurement Time and

Parameter

Immediately postoperative

Hb8 (g/L)

Platelets ( 109/L)

INR9

PTT10 (s)

Creatinine (mol/L)

Postoperative day 1

Hb (g/dL)

Platelets

INR

PTT (s)

Creatinine

IV (n 80)

Top IV

(n 80)

p

Value

101.6 13.6

168.8 44.7

1.4 0.2

38.2 10.9

105.1 79.1

102.9 10.9

163.9 60.1

1.4 0.1

38.0 16.0

94.2 29.2

0.52

0.56

0.55

0.91

0.25

100.3 13.9

186.6 56.0

1.3 0.11

34.4 5.1

115.3 108.8

102.3 13.1

180.2 66.2

1.3 0.1

33.6 8.2

97.2 37.8

0.35

0.51

0.08*

0.51

0.15

Abbreviations: Hb, hemoglobin; INR, international normalized ratio;

PTT, partial thromboplastin time.

*Compared using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 6. Observed Adverse Events

Observed Outcome (No./%)

Cardiac death

Mortality

Myocardial infarction

Stroke

Atrial fibrillation

Renal failure

Respiratory failure

Cardiogenic shock

Reoperation

Postoperative seizure

IV (n 80)

Top IV (n 80)

p Value

0

1 (1.3)

0

3 (3.8)

4 (5.0)

0

1 (1.3)

1 (1.3)

1 (1.3)

0

0

0

0

2 (2.5)

3 (3.8)

0

2 (2.5)

2 (2.5)

1 (1.3)

0

1

1

1

1

1

was not standardized. As a result, it was impossible to determine the amount of TXA absorbed into circulation in the

Top IV TXA group. This raised the possibility that the

beneficial effects in the combined administration group were

caused by the higher total dose of TXA rather than the route of

administration. However, a previous study found that TXA

applied topically to the pericardium was not absorbed into the

circulation10 in which case the systemic levels of TXA should

have been higher in the IV group.

The design of this study likely underestimated the beneficial effects in the Top IV group. The Top IV group

received 120 mL (100 mL of normal saline and 20 mL of

TXA) poured into the pericardial cavity, and an unknown

quantity subsequently was suctioned out and counted as

chest tube drainage, whereas the IV group received none.

Thus, a portion of the chest tube drainage measured postoperatively in the Top IV group included some of the 120

mL of solution poured into the pericardial cavity. As a

result, the beneficial effect of combined Top IV TXA was

greater than the results would suggest.

This study advances the current knowledge about the use

of TXA in cardiac surgery because it showed that combined

TXA administration may be more effective at reducing

blood loss after CABG surgery compared with only IV

administration. Although the difference may appear to be of

moderate clinical significance, it is important to recognize

that this difference was over and above that imparted by IV

TXA. This offered the potential for superior hemostasis

while avoiding the adverse events13,14 theoretically associated with high-dose IV TXA.

Prospective, randomized controlled studies with standardized TXA dosing and systemic TXA determinations are

warranted to determine the clinical relevance and safety

profile of combined topical and IV TXA. Such studies will

determine whether combined topical and IV TXA would be

a valuable addition to existing multimodal blood conservation strategies.

REFERENCES

1. Hutton B, Fergusson D, Tinmouth A, et al: Transfusion rates vary

significantly amongst Canadian medical centres. Can J Anaesth 52:581590, 2005

2. Society of Thoracic Surgeons Blood Conservation Guideline

Task Force, Ferraris VA, Ferraris SP, Saha SP, et al: Perioperative

blood transfusion and blood conservation in cardiac surgery: The

Society of Thoracic Surgeons and The Society of Cardiovascular

Anesthesiologists clinical practice guidelines. Ann Thorac Surg 83:

S27-S86, 2007

3. Tabuchi N, de HJ, Boonstra PW, et al: Activation of fibrinolysis

in the pericardial cavity during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac

Cardiovasc Surg 106:828-833, 1993

22

4. Khalil PN, Ismail M, Kalmar P, et al: Activation of fibrinolysis in

the pericardial cavity after cardiopulmonary bypass. Thromb Haemost

92:568-574, 2004

5. Henry DA, Carless PA, Moxey AJ, et al: Anti-fibrinolytic use for

minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD:001886, 2007

6. Abrishami A, Chung F, Wong J: Topical application of antifibrinolytic drugs for on-pump cardiac surgery: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth 56:202-212, 2009

7. Fawzy H, Elmistekawy E, Bonneau D, et al: Can local application

of tranexamic acid reduce post-coronary bypass surgery blood loss? A

randomized controlled trial. J Cardiothorac Surg 4:25, 2009

8. Baric D, Biocina B, Unic D, et al: Topical use of antifibrinolytic

agents reduces postoperative bleeding: A double-blind, prospective,

randomized study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 31:366-371, 2007

9. Abul-Azm A, Abdullah KM: Effect of topical tranexamic acid in

open heart surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol 23:380-384, 2006

MAHAFFEY ET AL

10. De Bonis M, Cavaliere F, Alessandrini F, et al: Topical use of

tranexamic acid in coronary artery bypass operations: A double-blind,

prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 119:575-580, 2000

11. Karthik S, Grayson AD, McCarron EE, et al: Reexploration for

bleeding after coronary artery bypass surgery: Risk factors, outcomes,

and the effect of time delay. Ann Thorac Surg 78:527-534, 2004

12. Despotis GJ, Filos KS, Zoys TN, et al: Factors associated with

excessive postoperative blood loss and hemostatic transfusion requirements: A multivariate analysis in cardiac surgical patients. Anesth

Analg 82:13-21, 1996

13. Murkin JM, Falter F, Granton J, et al: High-dose tranexamic

acid is associated with nonischemic clinical seizures in cardiac surgical

patients. Anesth Analg 110:350-353, 2010

14. Casati V: About dosage schemes and safety of tranexamic acid

in cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 99:236, 2003

You might also like

- Co MonitoringDocument9 pagesCo MonitoringSiva SankarNo ratings yet

- CamScanner Docs Scanned QuicklyDocument3 pagesCamScanner Docs Scanned QuicklySiva SankarNo ratings yet

- Indian Bank ChallanDocument1 pageIndian Bank ChallanSiva SankarNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Management of Acquired Hemophilia A: A Case Report and Review of LiteratureDocument3 pagesPerioperative Management of Acquired Hemophilia A: A Case Report and Review of LiteratureSiva SankarNo ratings yet

- My Garden Class 1Document20 pagesMy Garden Class 1Siva SankarNo ratings yet

- Sedation and Anesthesia in GI Endoscopy 2008Document12 pagesSedation and Anesthesia in GI Endoscopy 2008Siva SankarNo ratings yet

- Elsevier Opinion Piece Nov2017Document3 pagesElsevier Opinion Piece Nov2017Jilani ShaikNo ratings yet

- ARDSDocument7 pagesARDSSiva SankarNo ratings yet

- Transfer Professional LicenseDocument8 pagesTransfer Professional LicenseSiva SankarNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For PhysiciansDocument38 pagesGuidelines For PhysiciansSiva SankarNo ratings yet

- An Unusual Cause of Fat Embolism Syndrome.36Document3 pagesAn Unusual Cause of Fat Embolism Syndrome.36Siva SankarNo ratings yet

- DNB Final BS Revised 2016Document68 pagesDNB Final BS Revised 2016Kaustubh LanjeNo ratings yet

- H, C Radiolabeled Compounds and Their Applications in Metabolism StudyDocument5 pagesH, C Radiolabeled Compounds and Their Applications in Metabolism StudySiva SankarNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound Guided Regional Nerve BlocksDocument32 pagesUltrasound Guided Regional Nerve BlocksSiva SankarNo ratings yet

- Obesity 2Document12 pagesObesity 2Siva SankarNo ratings yet

- Br. J. Anaesth.-2013-Desmet-445-52Document8 pagesBr. J. Anaesth.-2013-Desmet-445-52Siva SankarNo ratings yet

- Uterine Dehiscence During Initiation of Spinal.1Document2 pagesUterine Dehiscence During Initiation of Spinal.1Siva SankarNo ratings yet

- Br. J. Anaesth.-2010-Hong-506-10Document5 pagesBr. J. Anaesth.-2010-Hong-506-10Siva SankarNo ratings yet

- Fox - Appendix R-Cox-regressionDocument18 pagesFox - Appendix R-Cox-regressionlinadiazbejarNo ratings yet

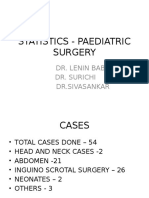

- Statistics - Paediatric SurgeryDocument9 pagesStatistics - Paediatric SurgerySiva SankarNo ratings yet

- AllotemntResultMedical PDFDocument170 pagesAllotemntResultMedical PDFShoyeb KhanNo ratings yet

- SR-JR Leave FormDocument5 pagesSR-JR Leave FormSiva SankarNo ratings yet

- Statistics - Paediatric SurgeryDocument9 pagesStatistics - Paediatric SurgerySiva SankarNo ratings yet

- Bank StatementDocument3 pagesBank Statementsaravanan_sfp100% (1)

- Ot 1 &2 Total Time Jan 2014Document6 pagesOt 1 &2 Total Time Jan 2014Siva SankarNo ratings yet

- OT1&2time-ASA, Surgery Stat FormDocument1 pageOT1&2time-ASA, Surgery Stat FormSiva SankarNo ratings yet

- Polytrauma Patient Death from Sepsis ComplicationsDocument3 pagesPolytrauma Patient Death from Sepsis ComplicationsSiva SankarNo ratings yet

- Case of Adverse Cardiac EventDocument17 pagesCase of Adverse Cardiac EventSiva SankarNo ratings yet

- Log Book JuneDocument10 pagesLog Book JuneSiva SankarNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Chiropractic Treatment Techniques-2016Document9 pagesChiropractic Treatment Techniques-2016Dr. Mateen ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Auxiliary VerbsDocument12 pagesAuxiliary VerbsNoe Lia CastroNo ratings yet

- Human Cannibalism 1Document8 pagesHuman Cannibalism 1api-409100981No ratings yet

- New Drugs 2014-2018Document31 pagesNew Drugs 2014-2018Prem Goel0% (1)

- Scientific Breakthroughs in Autophagy MechanismsDocument7 pagesScientific Breakthroughs in Autophagy MechanismshananNo ratings yet

- Parasitology study table overviewDocument10 pagesParasitology study table overviewBashaer GellehNo ratings yet

- Letter WritingDocument17 pagesLetter WritingEmtiaj RahmanNo ratings yet

- Physiology of Sleep: Michael Schupp MD FRCA Christopher D Hanning MD FRCADocument6 pagesPhysiology of Sleep: Michael Schupp MD FRCA Christopher D Hanning MD FRCArichie_ciandraNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Acute GastroenteritisDocument5 pagesPathophysiology of Acute Gastroenteritisheron_bayanin_15No ratings yet

- Epstein Barr VirusDocument13 pagesEpstein Barr VirusDianaLorenaNo ratings yet

- Expressed Emotion and RelapseDocument31 pagesExpressed Emotion and RelapseshivangifbscNo ratings yet

- WHATs New in CPCRDocument4 pagesWHATs New in CPCRJessicaHernandezNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry Assignment: On Acid-Base BalanceDocument4 pagesBiochemistry Assignment: On Acid-Base BalanceMuhammed ElRakabawiNo ratings yet

- Phet Natural SelectionDocument6 pagesPhet Natural Selectionapi-315485944No ratings yet

- Rundown Iomu 071019 - 08.10 PDFDocument13 pagesRundown Iomu 071019 - 08.10 PDFEfi OctavianyNo ratings yet

- Mitochondrial Cytopathies in Children and AdultsDocument28 pagesMitochondrial Cytopathies in Children and AdultsmmaitehmdNo ratings yet

- Internship Report JackDocument85 pagesInternship Report JackdamarismagererNo ratings yet

- 2024 - ĐỀ 4Document10 pages2024 - ĐỀ 4ellypham1357No ratings yet

- The Neurological History Taking: Osheik Seidi Sunderland Royal Hospital UKDocument38 pagesThe Neurological History Taking: Osheik Seidi Sunderland Royal Hospital UKHassen Kavi Isse100% (3)

- HRCA GK Quiz Syllabus Class 7-8Document19 pagesHRCA GK Quiz Syllabus Class 7-8Sualiha MalikNo ratings yet

- Asthma Lesson PlanDocument26 pagesAsthma Lesson PlanBharat Singh BanshiwalNo ratings yet

- JUUL Labs, Inc. Class Action Complaint - January 30, 2019Document384 pagesJUUL Labs, Inc. Class Action Complaint - January 30, 2019Neil MakhijaNo ratings yet

- Hipocrates - VOLUME 6Document400 pagesHipocrates - VOLUME 6Heitor Murillo CarnioNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmic Drops 101Document9 pagesOphthalmic Drops 101David NgNo ratings yet

- Gastrointestinal Tract Infections: General ConsiderationsDocument17 pagesGastrointestinal Tract Infections: General ConsiderationsDarpan GelalNo ratings yet

- Alex Cox Death 911 Call TranscriptDocument10 pagesAlex Cox Death 911 Call Transcripttmiller696733% (3)

- 3rd Periodical Grade 10Document3 pages3rd Periodical Grade 10diomedescolar.13No ratings yet

- Indian Herbs Cooking GuideDocument37 pagesIndian Herbs Cooking Guidehitesh mendirattaNo ratings yet

- 1.A Ndera CaseDocument13 pages1.A Ndera CaseNsengimana Eric MaxigyNo ratings yet

- Fall 2010 Eco Newsletter, EcoSuperiorDocument12 pagesFall 2010 Eco Newsletter, EcoSuperiorEco SuperiorNo ratings yet