Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Family Caregiving of Aging Adults With Down Syndrome

Uploaded by

Nor HatieykalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Family Caregiving of Aging Adults With Down Syndrome

Uploaded by

Nor HatieykalCopyright:

Available Formats

bs_bs_banner

Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities

Volume 13 Number 2 pp 181189 June 2016

doi: 10.1111/jppi.12153

Family Caregiving of Aging Adults

With Down Syndrome

Robert M. Hodapp*,, Meghan M. Burke, Crystal I. Finley*,, and Richard C. Urbano*,

*Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA; Department of Special Education, Peabody College,

Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA; Department of Special Education, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign,

Champaign, IL, USA; and Department of Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University Medical School, Nashville, TN, USA

Abstract

Although persons with Down syndrome now live to approximately 60 years, the implications of increased longevity on family caregiving have received inadequate attention. Even compared with adults with other types of intellectual disabilities, by their late 40s

and 50s adults with Down syndrome often show multiple health problems, cognitive-adaptive declines, and changes in daily work

and activities. If alive, their parents are more often elderly, as mothers give birth to newborns with Down syndrome at a median age

of 32 years (with high percentages age 40 and older). In addition, higher percentages of adults with (vs. without) Down syndrome

live in their family homes and greater percentages may ultimately reside with siblings. Compared with caring for other adults with

intellectual disabilities, aging adults with Down syndrome may present earlierand possibly more severe and more health-related

caregiving challenges to their parents and siblings. As a field and as a society, the authors note that we need to promote revisions of

family support policies and interventions; recognize the inter-relations of aging-related changes and their effects; and anticipate how

aging-related changes in the brothersister with Down syndrome and the parent(s) might affect sibling caregivers.

Keywords: adult siblings, aging-related health and functional decline, Down syndrome, family caregiving, intellectual disability,

older mothers

Introduction

Of the many modern-day successes in the field of intellectual

disabilities, perhaps most striking is the increasing life expectancy

of individuals with Down syndrome. From a median lifespan of

9 years during the 1920s (Penrose, 1949), individuals with Down

syndrome now live to approximately 60 years (Zigman, 2013). In

addition, such increases appear to be continuing. Consider, for

example, the change from the mid-1980s, when median life spans

were estimated to be 2530 years, until todays near-60 year life

span (Yang, Rasmussen, & Friedman, 2002; see also Janicki, Dalton, Henderson, & Davidson, 1999). Although various changes

have been ascribed to explain increasing longevity, from better

health care to more active involvement in the community, in

most industrialized societies persons with Down syndrome enjoy

increasingly long lives.

Although a cause for celebration, increasing longevity also

brings forth important implications for the families of these

adults. On the most obvious level, when an adult with disabilities

lives longer, families must consider potential changes in the priReceived March 12, 2015; accepted October 21, 2015

Correspondence: Richard C. Urbano, Pediatrics and Vanderbilt Kennedy

Center, Vanderbilt University, PMB 40, 230 Appleton Place, Nashville, TN

37212, USA. Tel: 11 615 875-9659; Fax: 11 615 322-8236;

E-mail: richard.urbano@gmail.com

mary carer. Forty-years ago, when individuals with Down syndrome lived only into their 30s, their parents would usually

outlive them. With life expectancies of persons with Down syndrome now at 60 years or more, fewer parents can be expected to

outlive their offspring. As a resultand considering the inadequacy of adult-disability services in the United States (National

Council on Disability, 2005) and in most industrialized nations

(World Health Organization, 2011)others in the family need

to assume increased caregiving responsibilities.

In this article, we go beyond this obvious change to explore

growing issues of family caregiving for aging adults with Down

syndrome. To state our argument, aging-related caregiving begins

as early as the mid-late 40s for many adults with Down syndrome, who by their late 40s often show health, cognitiveadaptive, and vocational declines. Such caregiving is performed

by parents who are older and may be more infirm, even though

adults with Down syndrome may more often live in their parental homes or with siblings. As a result, adult siblings may need to

assume high levels of care at earlier ages.

This triad of premature aging among adults with Down syndrome, parents who are older, and family caregiving that is more

common may make caregiving different when the adult has

Down syndrome compared with when adults have other types of

intellectual disability (ID). At this point, however, we simply

hypothesize that such differences may exist. In reviewing the

available evidence, we also note that the field has only begun to

C 2016 International Association for the Scientific Study of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

V

Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities

Volume 13 Number 2 June 2016

R. M. Hodapp et al. Family Caregiving of Aging Adults with Down Syndrome

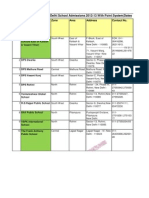

TABLE 1

Percentage of samples with specific or general health problems, by decade

Age groups

Problem

Study

Health condition studies

Visual impairment

Hearing impairment

Epilepsy

Dementia

Studies with measure of overall health

Medical change, past 5 years

Major health problem, past year

Poor-Fair overall health

20s

(8.8%)a

(13.3%)

(5.8%)

(5.0%)

(24.3%)

1

2

1

2

1

1

23.3%

7.7%

14.0%

7.7%

0.0%

3

4

5

17.4% (16.2%)

6.0%

30s

36.2%

11.5%

12.8%

9.8%

2.1%

0.0%

(11.6%)

(14.5%)

(6.3%)

(5.1%)

(21.9%)

(1.1%)

12.7% (13.8%)

40s

31.5%

19.0%

24.1%

9.9%

16.7%

22.2%

(17.6%)

(16.2%)

(6.5%)

(7.0%)

(18.5%)

(0.0%)

27.3% (28.0%)

50s

59.1%

18.6%

37.0%

13.7%

21.7%

45.7%

(20.2%)

(18.0%)

(15.2%)

(8.8%)

(12.2%)

(1.7%)

69.0% (37.0%)

38.5% (26.7%)

31.0%

Down syndrome % (Non-DS%, if available).

1 5 van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk et al. (1997; see their Table 2); 2 5 Stancliffe et al. (2012) (20s age-group 5 1829 years); 3 5 Patti et al. (2005);

4 5 Hodapp and Urbano (2007) (age-groups changed to decades); 5 5 Esbensen et al. (2013) (age-group 5 mean age of sample at testing).

examine these issues; as a by-product, our review reveals a critical

need for more research. Even basic issuesfor example, the general health of aging adults with Down syndrome or their residences during their later yearsare the subject of but a handful of

studies. Yet despite these limitations, we feel it necessary to call

attention to the aging-related changes in adults with Down syndrome, their parents, and their siblings. To the degree possible,

then, in the pages that follow we document these syndromespecific findings, before ending with practical and policy recommendations for caregiving in families of aging adults with Down

syndrome.

Aging in Down Syndrome: Three

Hypothesized Differences

Like anyone else, individuals with Down syndrome age and

experience aging-related health and functional declines. In the

case of Down syndrome, however, three features seem to influence the timing and nature of care needs for these aging adults.

Old Age in Down Syndrome Begins Earlier and is

Accompanied by Aging-related Health, Adaptive,

and Vocational Changes

To most of us, old age might be considered the retirement

years, beginning at age 65 or 70 and continuing until death. At

around these ages, one expects to develop a variety of agingrelated health problems and, in some cases, to need more intensive, individualized care. In Down syndrome old age starts earlier,

generally at age 45 or 50. In Down syndrome health research,

most studies categorize older adults as those age either 40 or 50

182

and older (Torr, Strydom, Patti, & Jokinen, 2010), and recent

examinations based on DNA methylation levels have found that

trisomy 21 leads to premature aging across different cell types, on

average by 6.6 years (up to 11.5 years for brain cells; Horvath

et al., 2015).

In Table 1, we document what might be called the infirmities

of old age. The table is divided into two studies that directly

report one or more specific medical problems, along with a bottom section of studies that, though not focused on medical conditions, report on the overall health status of their participants.

The first study, by Van Schrojenstein Lantman-deValk et al.

(1997), involved 1,602 persons with ID who lived in either institutions or group homes in two southern Dutch provinces (the

authors note that, in the Netherlands, only 2-5% of people with

ID older than 50 years live with their families, p. 43). Of these

individuals, 243 had Down syndrome (which was not further

broken down by age-groups). As shown in the table, the percentages of specific aging conditionsincluding visual impairments,

hearing impairments, epilepsy, and dementiadiffered for adults

with and without Down syndrome who were in their 40s and

50s. By the 40s and 50s, large percentages of adults with Down

syndrome showed one or more aging-related conditions, and

such percentages often greatly exceeded percentages shown by

adults with (non-DS) intellectual disabilities.

The Stancliffe et al. (2012) study also found that substantial

percentages of adults with Down syndrome displayed these problems during their 40s and 50s, though the two groups often did

not differ. But we also note that Stancliffe et al. (2012), while

studying large numbers of participants, was limited to only those

adults with ID in 25 American states who received adult disability

services. Across the United States, however, estimates are that

only 25% of all adults with intellectual disabilities receive staterun disability services, whereas 75% do not (Hewitt, 2014).

Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities

Volume 13 Number 2 June 2016

R. M. Hodapp et al. Family Caregiving of Aging Adults with Down Syndrome

How, then, do the 25% receiving services differ from the 75%

not receiving services? We do not know. Compared with the Van

Schrojenstein Lantman-deValk et al. (1997) and to other studies

at the bottom of Table 1, however, the Stancliffe et al. study seems

anomalous.

In the lower part of Table 1, we summarize old-age declines

through several studies that did not exclusively focus on health

per se. Esbensen, Mailick, and Silverman (2013) longitudinally

examined 75 home-living adults when they averaged 28 years

and then again at 52 years. Carers were asked about the general

health of their adult with Down syndrome using a simple, singlequestion measure which has proven remarkably predictive of

actual health status (Idler & Benyamini, 1997). In Hodapp and

Urbano (2007same data set as in Hodapp, Finley, & Urbano,

2016), siblings of over 1,100 adults with disabilities were surveyed; 216 of these adults were 2059-year-olds with Down syndrome, 416 were 20-59-year-old adults with non-DS intellectual

disabilities (both groups lived either at home or in a variety of

out-of-home settings). In the final study, Patti, Amble, and Flory

(2005) examined diagnostic and research clinic participants,

including 108 adults with Down syndrome and 43 with nonDown syndrome ID (adults in both samples were aged 5059

years). Through a review of clinical and medical records of each

person, coders examined four different types of life changes,

including the presence or absence of medical changes that had

occurred over the past 5 years.

In all three studies, increased percentages of health problems

or declines occurred over age groups; especially during the 50s,

higher percentages of adults with Down syndrome (vs. with intellectual disabilities) showed declining health. Among adults with

Down syndrome aged 5059 (as opposed to earlier age groups),

increases were apparent in the percentages showing a major

health problem in the past year (Hodapp & Urbano, 2007) or

who showed poor-fair overall health (Esbensen et al., 2013). In

the two studies that compared same-age adults with and without

Down syndrome, the 5059-year-olds with Down syndromeas

compared with 5059-year-olds with (non-DS) IDdisplayed

higher percentages of major health problems within the past year

(Hodapp & Urbano, 2007) or over the past 5 years (Patti et al.,

2005). Granted, individual studies were limited by having crosssectional (not longitudinal) designs; no direct comparison of

groups with and without Down syndrome; health status designations that relied on reports from siblings, carers, or clinical

records; and/or small participant numbers, especially at the older

ages. Still, findings seem fairly consistent across these diverse

studies.

Going beyond health per se, one might also examine agingrelated changes in relation to cognitive and adaptive behavior.

Again, few studies exist, with none featuring designs that are longitudinal and that compare adults with and without Down syndrome. Still, two longitudinal studies document similar agerelated changes in cognitive and adaptive functioning among

adults with Down syndrome. In the first, Oliver, Crayton, Holland, Hall, and Bradbury (1998) examined 57 adults with Down

syndrome, all of whom were 30 years or older and repeatedly

tested over a 4-year span. Three neuropsychological tests (simple

tests of aphasia, agnosia, and apraxia) were administered and the

authors tabulated a composite index of cognitive functioning.

Examining mean scores longitudinally, the subgroup who did

not show declines was younger at first testing (40.33 years)

than the subgroup showing declines (47.99 years). Although

participant numbers became small in later age groups, higher

percentages of adults showed composite declines when initial

testing began at older ages: percentages of composite declines

were 11.8% (2 of 17) of those tested during the 30s, 23% (6 of

26) during the 40s, and 70% (7 of 10) during their 50s. Moreover, all participants showing the most severe test-to-retest

declines were in their 40s (11.5% of age group) or 50s (40% of

age group).

Similar results were noted in a longitudinal study of adaptive

behavior over a 4-year period. Considering as clinically significant any decline in which the individual scored 25 or more

points lower across testing on the Adaptive Behavior Scales (ABS;

Fogelman, 1975), Collacott and Cooper (1997) examined 83

adults with Down syndrome, with the original ABS administration to carers when adults were in their 20s (n 5 19), 30s

(n 5 20), 40s (n 5 20), 50s (n 5 20), and 60s (n 5 4). Major

declines were noted in 10% of participants whose initial assessment occurred in their 20s, 5% of those in their 30s, 25% of

those in their 40s, 65% of those in their 50s, and 100% (all four

participants) of those in their 60s. In addition to these studies

that highlight the percentages of samples with declines or problems, mean-score declines across the 40s and 50s have also been

noted longitudinally (e.g., Carr & Collins, 2014, until 47 years),

cross-sectionally across decades (e.g., Tsao, Kindelberger, Freminville, Touraine, & Busssy, 2015), and in cross-sequential designs

that followed different-age individuals over multiyear spans

(Maaskant et al., 1996; Zigman, Schupf, Urv, Zigman, & Silverman, 2002).

Notably, most studies do not differentiate those adults with

Down syndrome who do and who do not show Alzheimers

dementia. We acknowledge the many debates in this area, particularly whether cognitive, linguistic, or adaptive skills decline for

those individuals without dementia over the 40s or 50s (cf. Hawkins, Eklund, James, & Foose, 2003; Rondal, 2009). From the perspectives of mothers, fathers, siblings, and individuals with

Down syndrome, however, combined-sample percentages (i.e., of

participants with and without dementia) better inform families

just how frequently such health conditions and cognitiveadaptive declines may be occurring among these aging adults.

An additional aging-related change concerns work activities.

Figure 1 shows the percentages of three levels of work-daily activities for adults with Down syndrome vs. those of adults with

(non-DS) ID. These data were reanalyzed from our earlier study

of work among adults with intellectual disabilities, with a specific

focus on correlates of those adults who had no work or daily

activity whatsoever (Taylor & Hodapp, 2012). For Figure 1,

groups are divided into the 216 participants with Down syndrome (left-side bars) and the 416 with intellectual disabilities,

but not Down syndrome (right-side bars). These cross-sectional

groups, comprised those who were in their 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s,

varied greatly in size, ranging from 69 participants in the 20s

group to 26 in the 50s group for those with Down syndrome,

from 119 in the 20s group to 90 in the 50s group for those with

(non-DS) ID.

Using this 2 (diagnostic group) by 4 (age-group) rubric, we

then examined each participants level of job or activity. Highlevel jobs were defined as when adults worked in the community,

183

Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities

Volume 13 Number 2 June 2016

R. M. Hodapp et al. Family Caregiving of Aging Adults with Down Syndrome

Offspring With Down Syndrome More Often

Have Older Parents

FIGURE 1

Proportion of adults with and without Down syndrome who

engage in higher-level, lower-level, or no work or activities, by

age group.

with varying levels of supports, as well as when adults were in

school or training for future jobs. Lower-level work-activity

included supervised workshops, prevocational training, volunteer

activities, and activity/day settings. Finally, we counted participants as having no job or activity when siblings checked that

their brothersister with disabilities Does not work or has no

activity setting.

Compared with those in their 20s and 30s, adults with Down

syndrome showed fairly marked changes in the 40s and 50s. Percentages of those working in high-level jobs declined rapidly,

from somewhere between 1/3 and 1/2 of participants in the 20s

and 30s, to smaller percentages in the 40s, before totally disappearing in the 50s; indeed, of 26 participants with Down syndrome aged 50 and above, none (0%) worked in high-level

community jobs (even with help or accommodations). Conversely, those with no job or activity doubled from the 20s30s to

the 40s (about 10%), before doubling again in the 50s (slightly

less than 20%). The middle barconstituting sheltered workshops, day programs, or activity settingsrose markedly in the

40s and 50s. Granted, these data were reported by siblings and

were cross-sectional. As a result, we cannot conclude that these

adults underwent changes over time, as conceivably adults with

Down syndrome who were in their 50s had never held jobs in the

community. Still, this change over age groups fits well with the

health, cognitive, and adaptive findings noted above. Although

similar changes across age-periods occurred in the non-DS group

(especially by the 50s), such changes were much less extreme

(e.g., among the 50-year-olds with non-DS intellectual disabilities, 15.6% worked in community jobs).

184

Although the focus of many public health studies, advanced

maternal age has received little attention in other areas of Down

syndrome research. During childhood, older motherswho are

more often better educated, married and less likely to divorce

generally provide their children more resources (McLanahan,

2004; in Down syndrome, see Hodapp, Burke, & Urbano, 2012),

but the issue of older-than-usual parents has less often been

explored during adulthood.

To document that mothers of offspring with Down syndrome

are indeed older, we compared the age distributions of mothers

who gave birth to infants with Down syndrome in the United

States (Martin, Hamilton, Osterman, Curtin, & Mathews, 2015),

the United Kingdom (Congenital Anomaly Statistics, 2010), and

Australia (Staples, Sutherland, Haan, & Clisby, 1991these data,

in particular, are somewhat dated). Across these three countries

(which differ somewhat in distributions), the 50%, 75%, and

90% maternal birth ages in the overall population were 27, 32,

and 37 years, respectively, whereas maternal ages at birth of the

newborn with Down syndrome were 32, 37, and 42 years, respectively. Compared with mothers in the general population, mothers of newborns with Down syndrome are, on average, roughly 5

years older.

For our purposes, having older parents involves age

differentials that continue throughout life. Thus, the mother who

is 35 years old at the birth of a newborn (a 0-year-old) is 70

years old when the offspring is 35; 80 years old when her offspring is 45. Fathers, who are generally 12 years older than their

wives, also have average life spans that are 45 years shorter. As a

result, when offspring with Down syndrome are in their late 40s

and 50s, and often coping with aging-related health problems

and adaptive-cognitive declines, their parents (if alive) are most

likely experiencing the aging-related issues of anyone who is in

their 70s and 80s.

Adults With Down Syndrome Experience Different

Forms of Family Caregiving

Although estimates vary, from 75% to 84% of all persons

with intellectual and developmental disabilities live with their

families (Fujiura, 2014). But as the field has begun to examine

residential issues for adults with Down syndrome, more specific

differences have also arisen. The first involves the age-related

nature of home living in adulthood (Hodapp et al., 2016; Stancliffe et al., 2012; Tsao et al., 2015). Across individuals with and

without Down syndrome, decreasing percentages of adults live in

their family homes across each decade of adulthood. Thus, higher

percentages live in the family home during the 20s, which

decreases during the 30s, decreasing again during the 40s and yet

again during the 50s. Especially, during the first two decades of

adulthoodwhen adults with ID are in their 20s and 30s

higher percentages of adults with (vs. without) Down syndrome

live with their parents. By the time these adults are in their 40s

and 50s, however, fewer live in their family home.

Figure 2 shows changes in percentages of adults with Down

syndrome who live in the parents home across decades for the

Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities

Volume 13 Number 2 June 2016

R. M. Hodapp et al. Family Caregiving of Aging Adults with Down Syndrome

FIGURE 2

Proportion of adults with Down syndrome who live in their

family homes from three recent studies, by age group.

three studies of this issue. Stancliffe et al. (2012) examined data

from the National Core Indicators (NCI) project, which examined

those individuals who received state disability services in 25 U.S.

states. Hodapp et al. (2016) analyzed the Adult Sibling Survey of

almost 1,200 adult American siblings from a web-based survey,

while Tsao et al. (2015) studied 120 French adults with Down syndrome who did not show Alzheimers dementia (providing participants living status by decade; Tsao et al.s Table 1, p. 6).

Despite differences in samples, study emphases, and methodologies, a similarthough not identicalpattern emerges across

studies. In all studies, high percentages of adults live in the family

home during the 20s and 30s. In the two studies that also examined adults with (non-DS) ID (Hodapp et al., 2016; Stancliffe

et al., 2012), overall home-living percentages among adults with

Down syndrome exceeded percentages of others with ID. In all

three studies, such home-living percentages changed over age

groups, with the percentages of adults with Down syndrome (and

without Down syndrome) declining across the decades. Within

the Down syndrome groups, the most striking changes occurred

from the 20s30s to the 40s (and 50s) in the Hodapp et al. (2016)

and Tsao et al. (2015) studies, whereas the Stancliffe et al. (2012)

study showed differences from the 20s to the 30s, the 30s to the

40s, and the 40s to the 50s. Thus, although all studies showed similar declining percentages of home-living adults across age-groups

(and, for those studies reporting both groups, among those with

and without Down syndrome), the exact timing of changes differed slightly. Although not reported by decade, Woodman, Mailick, Anderson, and Esbensen (2014) also noted that, among those

who did move away from home, average ages of moving out of the

family home were younger among the Down syndrome vs. the

non-Down syndrome groups (although Woodman et al. also

found similar percentagesduring the mid-40sof each group in

each type of residential setting). Thus, though studies disagree to

some extent, adults with Down syndrome seem to more often

spend their 20s and 30s with their parents (possibly in higher percentages than do their non-Down syndrome age mates). Then, in

later decades, they move out of the family home.

A second recent suggestion concerns co-residing with siblings

after adults with Down syndrome leave their family homes. In

the Woodman et al. (2014) study noted above, high percentages

of adults with Down syndrome were reported to subsequently

reside with their siblings. Although Woodman et al. (2014) did

not specifically compare over 20 years time families of adults

with and without Down syndrome (only the group with Down

syndrome was followed over 20 years), After a 20-year period,

half of the adults with Down syndrome in family settings lived

with their adult siblings (Woodman et al., 2014, p. 508). Given

that the average age of these adults at final testing was 52 years,

only 35% lived with family members (either parents or siblings).

Of those who did live with relatives, however, half lived with

adult siblings. Thus, high percentages of adults with Down syndromeprobably between 10% and 20%ultimately live with

one of their adult siblings.

Although additional longitudinal and comparative studies are

neededand the few existing studies do differ to some extenta

reasonably clear picture still emerges. During their 20s and 30s,

most adults with Down syndrome seem fairly healthy, with stable

cognitive and adaptive functioning, and many work in the community. By their 50s, increasing percentages show specific health

conditions and fair-poor overall health, noticeable declines in

cognitive and adaptive skills, and few hold jobs in the community

(by the 50s, almost all hold either lower-level jobs-activities or

have no daily jobs or activities).

Important changes may also occur for parents, for where the

adult with Down syndrome lives, and involvement of siblings.

Thus, when parents care or oversee care for their 4050-year-old

offspring, they themselves are more often in their 70s or 80s and

presumably more often frail. The adults with Down syndrome,

who (compared with those without Down syndrome) more often

lived at home in their 20s and 30s, increasingly live away from

the family home. The familys other adult offspring, the siblings

of adults with Down syndrome, may also need to be involved

earlier, caring or overseeing care for their brothersister with

Down syndrome and their parents.

Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research

Although many implications could be drawn from the findings above, we, here, provide three policy recommendations,

along with some thoughts concerning future research.

Practical and Policy Recommendations

Supports for aging at non-old ages. Although a major

component of aging relates to planning for the future, most families of individuals with ID do not pursue future planning

(Freedman, Krauss, & Seltzer, 1997; Gilbert, Lankshear, &

Petersen, 2007; Heller & Factor, 1993; Weeks, Nilsson, Bryanton,

185

Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities

Volume 13 Number 2 June 2016

R. M. Hodapp et al. Family Caregiving of Aging Adults with Down Syndrome

& Kozma, 2009; see Lunsky, Tint, Robinson, Gordeyko, &

Ouellette-Kuntz, 2014 for a review). Families face many barriers

to future planning, including a lack of information, psychosocial

issues involved in addressing the topic, and trouble navigating

the service system. Yet without future planning, individuals with

ID are at risk for institutional care (McCann, Hebert, Bienias,

Morris, & Evans, 2004), losing benefits, and being in crisis situations (Heller & Caldwell, 2006). It is thus necessary for families

to begin future planning before a crisis occurs.

For individuals with Down syndrome and their families,

such aging-related issues need to be addressed at earlier ages.

As these adults often incur health and functional declines

beginning in their 40s (when parents are in their 70s or 80s),

future planning may need to occur while the adults are in their

30s and their parents are in their 60s. In addition, such future

planning should include individuals with Down syndrome

themselves. By educating these adults about future planning,

they can make more informed later-life decisions. Recognizing

the need to intervene earlier with adults with Down syndrome,

one training study of person-centered life planning included 60

adults with intellectual disabilities who were either 35 years or

older with Down syndrome or age 50 or older without Down

syndrome (Heller, Miller, Hsieh, & Sterns, 2000). Adults who

received the training (vs. those who did not) gained more

knowledge about future planning, made more choices over

time, and were more likely to reach their goals. Such interventions should be available for adults with Down syndrome when

they are in their 30s.

In addition, several existing services might focus more on

families of aging adults with Down syndrome. In the United

States, the Older Americans Act includes the National Family

Caregiver Support Program, which is intended to provide information, referral, counseling, and respite to carers. Unfortunately,

the Program is directed toward carers of older individuals (e.g.,

aging parents) or grandparents providing care to their children;

programming is not directed toward aging carers of individuals

with disabilities. The Older Americans Act also legislated the creation of Aging and Disability Resource Centers (ADRCs).

Although ADRCs help families navigate the service system, these

centers do not provide future planning services (though they do

provide web links to disability-related organizations; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013). Considering the

findings noted in this paper, the National Family Caregiver Support Program and ADRCs should be expanded to provide information, training, and support about future planning to aging

carers of individuals with Down syndrome.

Cascade of problems in the family. Especially in families of

adults with Down syndrome, policymakers need to emphasize

the multiple health problems facing both the adult and his or her

parents. Among adults with ID more generally, Krahn, Hammond, and Turner (2006) have noted a cascade of health problems relating to disparities in (1) health conditions, (2) attention

to care needs, (3) preventative care and health promotion practices, and (4) access to health care. These same health issues also

affect adults with Down syndrome, albeit at earlier ages. But such

issues also inter-relate. As opposed to other 50-year-olds with

ID, 50-year-olds with Down syndrome may experience worse

186

health problems (Table 1) as well as a greater number of negative

life events (Patti et al., 2005). As Jokinen, Janicki, Hogan, and

Force (2012) note, even planned-for transitions do not always go

smoothly, as when moving to an out-of-home placement is

unsuccessful or when parents who had been proactive become ill

and lose control over the transition process. For all individuals

with intellectual disabilities, such life events may relate to

increased risks of depression (Tsanikos, Bouras, Costello, & Holt,

2007). Specifically, for adults with Down syndrome, connections

have also been noted between depression and lower levels of

active engagement in employment and social activities (Mallardo,

Cuskelly, White, & Jobling, 2014; also Dykens et al., 2015), as

well as between bereavement and subsequent behavioral changes

and cognitive declines (Fonseca, Oliveira, Guilhoto, Cavalheiro,

& Bottino, 2014). With parents facing increased risks of dying or

of experiencing functional-health declines, adults with Down

syndrome in their 40s and 50s may face a cascade of changes to

themselves and to their parents.

Triad of caregiving. Given the aging of society in most industrialized countries, caregiving is becoming an increasingly important topic. Examining the demography of the U.S. population in

the context of caregiving by the Baby Boom generation (i.e.,

those born between 194664), Rogerson and Kim (2005) illustrated the ways in which the timing of marriage, childrearing

(essentially, a 30-year period), and caring for ones parents

(which they describe as mostly starting at age 75) can bring about

different versions of the sandwich generation, the phenomenon

of simultaneously caring for ones children and for ones parents.

The sandwich generation also applies to families of adults

with Down syndrome, but with two important differences. First,

though most siblings of adults with a disability will belong to the

sandwich generation, many (especially females; Orsmond & Seltzer, 2000) also expect to provide future care for their brothersister with disabilities (Burke, Taylor, Urbano, & Hodapp, 2012). In

the case of Down syndrome, some siblings may fulfill all three

caregiving roles simultaneously, experiencing the triple-decker

sandwich of caring for their aging parent(s), their own offspring,

and their brothersister with Down syndrome.

Second, though siblings of adults with Down syndrome may

be assuming these multiple carer roles, family support policies in

most countries either overlook or have only recently begun to

consider siblings. Consider the Family Medical Leave Act

(FMLA) in the United States. Signed into law in 1993, the FMLA

allows family members to take up to 12 work weeks of unpaid

leave to attend to the health conditions of themselves or their

parents, spouses, or children. Until recently, the language did not

specify whether adult siblings could access FMLA to care for their

brotherssisters with Down syndrome. In July 2015, the Department of Labor further expanded the definitions and contexts for

FMLA protections. Specifically, the changes now explicitly state

that a child can refer to an individual older than 18 who is

incapable of self-care because of a mental or physical disability

(U.S. Department of Labor, 2015). Additionally, the language

clarifies that anyone who acts in the place of a parent could

access FMLA protections. Such language could mean that siblings

can now access FMLA.

Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities

Volume 13 Number 2 June 2016

R. M. Hodapp et al. Family Caregiving of Aging Adults with Down Syndrome

A further complication involves the higher rates of adults

with Down syndrome who live with their adult sibling (Woodman, et al., 2014). In light of increased rates of co-residence with

siblings, policymakers should examine in-home supports. In one

recent estimate, the United States spent $61.2 billion on supports

for individuals with ID, even as only 6.7% was allocated to family

support (Braddock et al., 2015). Given that, even compared with

others with ID, adults with Down syndrome more often live with

family members (either parents or siblings), it seems crucial that

more funding and services be directed toward support that is

centered on family members.

Research Implications

In describing this complex set of decade-by-decade changes,

we are aware of the weaknesses of the available research. On

some topics, few studies even exist. Given the impending caregiving crisis, not nearly enough studies exist on aging parents, and

few examine siblings when their brothersister with Down syndrome is in their 40s and 50s. Even among studies of adults with

Down syndrome, their parents, or their siblings, these studies

vary in numbers of participants at various ages, with often only a

few at the later ages. Studies vary in whether they are crosssectional or longitudinal, in how recently they were conducted,

and in whether functioning levels of adults with Down syndrome

were directly tested or reported by a carer or sibling. Studies also

span a variety of industrialized countries, including the United

States, United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Australia, and France.

Beyond the scarcity of research, we also acknowledge that

studies focused exclusively on families of adults with Down syndrome run counter to several influential recommendations. In

looking toward the future of health research, for example, the

World Report on Disability (World Health Organization, 2011)

advocates that, wherever possible, mainstream research should

be performed, or research that examines the general population

and includes some individuals with disabilities. From the findings noted above, however, it may be essential to study families

of aging adults with Down syndrome. By comparing those aging

individuals vs. those without Down syndrome and their families,

we can better differentiate the changes and issues that are common to all families of aging individuals with intellectual disabilities, and those that seem unique to Down syndrome.

Finally, these findings strongly suggest that researchers

should more often employ a wider family perspective. In characterizing the decades of the 40s and 50s for adults with Down

syndrome and their families, changes are not confined to a single domain or to a single person (Janicki, Zendell, & DeHaven,

2010). For the adults themselves, findings relate to health, cognitive, adaptive, and vocational functioning; for parents, to their

own aging-related changes, which are exacerbated by offspring

who more often live at home and show old-age problems during

the middle-age years; for siblings, to family ties that foster caregiving by adult (mostly female) siblings for their brotherssisters with disabilities when parents can no longer do so. In short,

family caregiving during adulthood involves changes in multiple

domains across multiple people, each of which affects the person who is changing as well as everyone else.

Conclusion

Across the field of disability, the increased life expectancy of

persons with Down syndrome is among the most profound and

exciting of all changes. Like all changes, however, such increased

longevity brings forth its own, often unexpected implications. In

Down syndrome, these changes involve three sets of people:

adults with Down syndrome, their mothers and fathers, and one

or more adult siblings. Such changes involve health and functional declines of the offspring with Down syndrome and of the

parents, both occurring when adults with Down syndrome are in

their late 40s and 50s.

As with any societal change, we now need to embark on policies and practices to help these families cope in the best way possible. As an early attempt, this article documents changes that

routinely occur for aging adults with Down syndrome and their

families; more detailed studies will be needed in the future. But

beyond documenting these aging-related changes, we also need

to develop and implement policies to aid these families. Although

the specifics of such policies and practices will differ from one

country to another, all will necessarily involve addressing family

caregiving at earlier ages, more fully utilizing future planning,

and providing help and supports for aging adults with Down

syndrome, their parents, and their siblings.

References

Braddock, B., Hemp, R., Rizzolo, M. C., Tanis, E. S., Haffer, L., & Wu, J.

(2015). The state of the states in developmental disabilities (10th ed.).

Washington, DC: American Association on Intellectual and

Developmental Disabilities.

Burke, M. M., Taylor, J. L., Urbano, R. C., & Hodapp, R. M. (2012).

Predictors of future caregiving by adult siblings of individuals with

intellectual and developmental disabilities. American Journal on

Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117, 3347.

Carr, J., & Collins, S. (2014). Ageing and dementia in a longitudinal

study of a cohort with Down syndrome. Journal of Applied Research

in Intellectual Disabilities, 27, 555563.

Collacott, R. A., & Cooper, S. A. (1997). A five-year follow up study of

adaptive behaviour in adults with Down syndrome. Journal of

Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 22, 187197.

Congenital Anomaly Statistics, England and Wales (Series MB3). (2010).

Official National Statistics, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.ons.gov.

uk/ons/rel/vsob1/congenital-anomaly-statisticsengland-and-wales

series-mb3-/no232008/index.html.

Dykens, E. M., Shah, B., Davis, B., Baker, C., Fife, T., & Fitzpatrick, J.

(2015). Psychiatric disorders in adolescents and young adults with

Down syndrome and other intellectual disabilities. Journal of

Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 7, 18.

Esbensen, A. J., Mailick, M. R., & Silverman, W. (2013). Long-term

impact of parental well-being on adult outcomes and dementia

status in individuals with Down syndrome. American Journal on

Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 118, 294309.

Fogelman, C. J. (1975). AAMD adaptive behavior scale manual.

Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Deficiency.

Fonseca, L. M., de Oliveira, M. C., de Figueiredo, L. M., Guilhoto, F.,

Cavalheiro, E. A., & Bottino, C. M. (2014). Bereavement and

behavioral changes as risk factors for cognitive decline in adults with

Down syndrome. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 10, 2209

2219. http://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S68831

187

Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities

Volume 13 Number 2 June 2016

R. M. Hodapp et al. Family Caregiving of Aging Adults with Down Syndrome

Freedman, R., Krauss, M., & Seltzer, M. M. (1997). Aging parents

residential plans for adults with mental retardation. Mental

Retardation, 35, 114123.

Fujiura, G.T. (2014). The political arithmetic of disability and the

American family: A demographic perspective. Family Relations, 63,

719.

Gilbert, A., Lankshear, G., & Petersen, A. (2007). Older family-carers

views on the future accommodation needs of relatives who have an

intellectual disability. International Journal of Social Welfare, 17, 54

64.

Hawkins, B. A., Eklund, S. J., James, D. R., & Foose, A. K. (2003).

Adaptive behavior and cognitive function of adults with Down

syndrome: Modeling change with age. Mental Retardation, 41, 728.

Heller, T., & Caldwell, J. (2006). Supporting aging caregivers and adults

with developmental disabilities in future planning. Mental

Retardation, 44, 189202.

Heller, T., & Factor, A. (1993). Aging family caregivers: Support resources

and changes in burden and placement desire. American Journal of

Mental Retardation, 98, 417426.

Heller, T., Miller, A. B., Hsieh, K., & Sterns, H. (2000). Later-life

planning: Promoting knowledge of options and choice-making.

Mental Retardation, 38, 395406.

Hewitt, A. (2014). Embracing complexity: Community inclusion,

participation, and citizenship. Intellectual and Developmental

Disabilities, 52, 475495.

Hodapp, R. M., Burke, M. M., & Urbano, R. C. (2012). Whats age got to

do with it? Implications of maternal age on families of offspring with

Down syndrome. International Review of Research in Developmental

Disabilities, 42, 109145.

Hodapp, R. M., Finley, C. I., & Urbano, R. C. (2016). Changes during the

40s for adults with Down syndrome, their parents, and siblings.

Unpublished manuscript, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

Hodapp, R. M., & Urbano, R. C. (2007). Adult siblings of individuals

with Down syndrome versus with autism: Findings from a largescale American survey. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51,

10181029.

Horvath, S., Garagnani, P., Bacalini, M. G., Pirazzini, C., Salvioli, S.,

Gentilini, D., . . . Franceschi, C. (2015). Accelerated epigenetic aging

in Down syndrome. Aging Cell, 14, 15.

Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A

review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health &

Social Behavior, 38, 2137.

Janicki, M. P., Dalton, A. J., Henderson, C. M., & Davidson, P. W. (1999).

Mortality and morbidity among older adults with intellectual

disability: Health service considerations. Disability and Rehabilitation, 21, 284294.

Janicki, M. P, Zendell, A., & DeHaven, K. (2010). Coping with dementia

and older families of adults with Down syndrome. Dementia, 9, 391

407.

Jokinen, N. S., Janicki, M. P., Hogan, M., & Force, L. T. (2012). The

middle years and beyond: Transitions and families of adults with

Down syndrome. Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 18, 5969.

Krahn, G. L., Hammond, L., & Turner, A. (2006). A cascade of

disparities: Health and health care access for people with intellectual

disabilities. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 12,

7082.

Lunsky, Y., Tint, A., Robinson, S., Gordeyko, M., & Ouellette-Kuntz, H.

(2014). System-wide information about family carers of adults with

intellectual/developmental disabilities: A scoping review of the

literature. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 11,

818.

Maaskant, M. A., van den Akker, M., Kessels, A. G. H., Haveman, M. J.,

van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk, H. M. J., & Urlings, H. F. J.

(1996). Care dependence and activities of daily living in relation to

188

ageing: Results of a longitudinal study. Journal of Intellectual

Disability Research, 40, 535543.

Mallardo, M., Cuskelly, M., White, P., & Jobling, A. (2014). Mental

health problems in adults with Down syndrome and their

association with life circumstances. Journal of Mental Health Research

in Intellectual Disabilities, 7, 229245.

Martin, J., Hamilton, B., Osterman, M., Curtin, M., & Mathews, M.

(2015). Births: Final data for 2013Internet TABLES. In: National

Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 1 (Supplement). Retrieved from http://

www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_01_tables.pdf.

McCann, J. J., Hebert, L. E., Bienias, J. L., Morris, M. C., & Evans, D. A.

(2004). Predictors of beginning of and ending caregiving during a 3year period in a biracial community population of older adults.

American Journal of Public Health, 94, 18001806.

McLanahan, S. (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring

under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41,

607627.

National Council on Disability. (2005). The state of 21st century longterm services and supports: Financing and systems reform for

Americans with disabilities. Washington, DC: Author.

Oliver, C., Crayton, L., Holland, A., Hall, S., & Bradbury, J. (1998). A

four-year prospective study of age-related cognitive change in adults

with Downs syndrome. Psychological Medicine, 28, 13651377.

Orsmond, G. I., & Seltzer, M. M. (2000). Brothers and sisters of adults

with mental retardation: Gendered nature of the sibling relationship.

American Journal on Mental Retardation, 105, 486508.

Patti, P. J., Amble, K. B., & Flory, M. J. (2005). Life events in older adults

with intellectual disabilities: Differences between adults with and

without Down syndrome. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual

Disabilities, 2, 149155.

Penrose, L. S. (1949). The incidence of Mongolism in the general

population. Journal of Mental Science, 95, 685688.

Rogerson, P. A., & Kim, D. (2005). Population distribution and

redistribution of the baby-boom cohort in the United States:

Recent trends and implications. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102, 15319

15324.

Rondal, J. A. (2009). Psycholinguistique du handicap mental [Psycholinguistics of mental disability]. Marseilles, France: Solal.

Stancliffe, R. J., Lakin, C. K., Larsen, S. A., Engler, J., Taub, S., Fortune, J.,

& Bershadsky, J. (2012). Demographic characteristics, health

conditions, and residential service use in adults with Down syndrome in 25 U.S. states. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities,

50, 92108.

Staples, A. J., Sutherland, G. R., Haan, E. A., & Clisby, S. (1991).

Epidemiology of Down syndrome in South Australia, 1960-89.

American Journal of Human Genetics, 49, 10141024.

Taylor, J. L., & Hodapp, R. M. (2012). Doing nothing: Adults

with disabilities with no daily activities and their siblings.

American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities,

117, 6779.

Torr, J., Strydom, A., Patti, P., & Jokinen, N. (2010). Aging in Down

syndrome: Morbidity and mortality. Journal of Policy and Practice in

Intellectual Disabilities. 7, 7081.

Tsao, R., Kindelberger, C., Freminville, B., Touraine, R., & Bussy, G.

(2015). Variability of the aging process in dementia-free adults with

Down syndrome. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental

Disabilities, 120, 315.

Tsanikos, E., Bouras, N., Costello, H., & Holt, G. (2007). Multiple

exposure to life events and clinical psychopathology in adults with

intellectual disability. Social Psychiatry: Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42,

2428.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2013). Administration

for community living, help and resources, people with disabilities. Re-

Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities

Volume 13 Number 2 June 2016

R. M. Hodapp et al. Family Caregiving of Aging Adults with Down Syndrome

trieved from www.acl.gov/Get_Help/Help_Indiv_Disabilities/Index.

aspx.

U.S. Department of Labor. (2015). Fact Sheet #28K: Son or Daughter 18

years of age and older under the Family and Medical Leave Act.

Retrieved from http://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/whdfs28k.

pdf.

Van Schrojenstein Lantman-deValk, H. M. J., van den Akker, M.,

Maaskant, M. A., Haveman, M. J., Urlings, H. F. J., Kessels, A. G. H.,

& Crebolder, H. F. J. M. (1997). Prevalence and incidence of health

problems in people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual

Disability Research, 41, 4251.

Weeks, L. E., Nilsson, T., Bryanton, O., & Kozma, A. (2009). Current and

future concerns of older parents of sons and daughters with

intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual

Disabilities, 6, 180188.

Woodman, A. C., Mailick, M. R., Anderson, K. A., & Esbensen, A.

(2014). Residential transitions among adults with intellectual

disability across 20 years. American Journal on Intellectual and

Developmental Disabilities, 119, 496515.

World Health Organization. (2011). World report on disability. Retrieved

from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789240685215_eng.

pdf?ua51.

Yang, Q., Rasmussen, S. A., & Friedman, J. M. (2002). Mortality

associated with Downs syndrome in the USA from 1983 to 1997: A

population-based study. Lancet, 359, 10191025.

Zigman, W. B. (2013). Atypical aging in Down syndrome. Developmental

Disabilities Research Reviews, 18, 5167.

Zigman, W. B., Schupf, N., Urv, T., Zigman, A., & Silverman, W. (2002).

Incidence and temporal patterns of adaptive behavior change in

adults with mental retardation. American Journal on Mental

Retardation, 107, 161174.

189

You might also like

- Mental Health, Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and the Ageing ProcessFrom EverandMental Health, Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and the Ageing ProcessNo ratings yet

- Antisocial Article2Document11 pagesAntisocial Article2mimirozmiza7No ratings yet

- Parent and Child Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Mental Illness: A Pilot StudyDocument11 pagesParent and Child Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Mental Illness: A Pilot StudySteluta AureliaNo ratings yet

- World Health Day 2013Document64 pagesWorld Health Day 2013koromakNo ratings yet

- Australians With DSDocument6 pagesAustralians With DSTina MorleyNo ratings yet

- SociologyDocument5 pagesSociologyBRIAN KIPTOONo ratings yet

- Down Syndrome Research Paper ExampleDocument4 pagesDown Syndrome Research Paper Exampleafeaxlaaa100% (3)

- Down Syndrome Research Paper ThesisDocument4 pagesDown Syndrome Research Paper Thesisfvg4mn01100% (1)

- World Psychiatry - 2022 - Reynolds - Mental Health Care For Older Adults Recent Advances and New Directions in ClinicalDocument28 pagesWorld Psychiatry - 2022 - Reynolds - Mental Health Care For Older Adults Recent Advances and New Directions in ClinicalpujakpathakNo ratings yet

- 2016 O Neill Anxiety and Depression Symptomatology in Adult Siblings of Individuals With Different Developmental Disability DiagnosesDocument10 pages2016 O Neill Anxiety and Depression Symptomatology in Adult Siblings of Individuals With Different Developmental Disability Diagnosesnermal93No ratings yet

- Human Gen Journal ReviewDocument7 pagesHuman Gen Journal ReviewAlleah AlvizNo ratings yet

- NDIS assessment tools must understand Down syndromeDocument5 pagesNDIS assessment tools must understand Down syndromeEdgar DiplomadoNo ratings yet

- Mental Health of Older Adults: Facts, Risks & WHO ResponseDocument6 pagesMental Health of Older Adults: Facts, Risks & WHO Responsesergius3No ratings yet

- Free Research Papers On Down SyndromeDocument5 pagesFree Research Papers On Down Syndromegzvp7c8x100% (1)

- Journal of DisabilityDocument162 pagesJournal of DisabilityMago Hugo HugoNo ratings yet

- Kes Fam - IlyDocument23 pagesKes Fam - Ilyfaridnugroho5No ratings yet

- Document 1Document13 pagesDocument 1api-654955897No ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics Down SyndromeDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Topics Down Syndromelbiscyrif100% (1)

- Aging and Down Syndrome A Health and Well-Being GuidebookDocument44 pagesAging and Down Syndrome A Health and Well-Being GuidebookNicoleNo ratings yet

- Chronic Illness Stress and AgeDocument8 pagesChronic Illness Stress and AgeMolofaneNo ratings yet

- 2016 - Research Brief - Ageing PerceptionsDocument5 pages2016 - Research Brief - Ageing PerceptionsRhoda Mae JapsayNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Down Syndrome PDFDocument6 pagesThesis On Down Syndrome PDFHelpWithWritingPaperUK100% (1)

- Argumentative Essay FinalDocument10 pagesArgumentative Essay Finalapi-550035247No ratings yet

- Issue Brief Final DraftDocument15 pagesIssue Brief Final Draftapi-664663354No ratings yet

- Down Syndrome Research PaperDocument8 pagesDown Syndrome Research Paperapi-585725638No ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics On Down SyndromeDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Topics On Down Syndrometkpmzasif100% (1)

- Psychiatric ProblemsDocument4 pagesPsychiatric ProblemsAce VendNo ratings yet

- Jama Vahia 2020 VP 200231 1607119495.51442Document2 pagesJama Vahia 2020 VP 200231 1607119495.51442Febria Rike ErlianaNo ratings yet

- Older Adults and Mental Health Effect On Covid 19Document2 pagesOlder Adults and Mental Health Effect On Covid 19Roshin Mae E. TejeroNo ratings yet

- Retrieve 5Document7 pagesRetrieve 5api-664106052No ratings yet

- Level of Growth and Development 3.3.1 Normal Development of A Young Adult (Potter and Perry)Document59 pagesLevel of Growth and Development 3.3.1 Normal Development of A Young Adult (Potter and Perry)Jack BangcoyoNo ratings yet

- Good Thesis Statement For Down SyndromeDocument5 pagesGood Thesis Statement For Down Syndromejamiemillerpeoria100% (2)

- Research Paper of Down SyndromeDocument7 pagesResearch Paper of Down Syndromegw13qds8100% (1)

- Down SyndromeDocument6 pagesDown Syndromeapi-543197223No ratings yet

- Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorders OutcomesDocument9 pagesAdults With Autism Spectrum Disorders OutcomesAnaLaura JulcahuancaNo ratings yet

- IntroductionPublic Health Is One of The Most Important Aspects of National Interest For Any CountryDocument10 pagesIntroductionPublic Health Is One of The Most Important Aspects of National Interest For Any CountrySammy GitauNo ratings yet

- Stephaniejanzen15 11 2012Document13 pagesStephaniejanzen15 11 2012api-258330934No ratings yet

- DokumenDocument6 pagesDokumenDeri DarmawanNo ratings yet

- DownDocument43 pagesDownAndrea LópezNo ratings yet

- Thesis About Down SyndromeDocument8 pagesThesis About Down Syndromerebeccaevansspringfield100% (2)

- Early Adulthood Developmental PsychologyDocument4 pagesEarly Adulthood Developmental PsychologyJan Aguilar EstefaniNo ratings yet

- Autism Spectrum Disorder: Outcomes in Adulthood: ReviewDocument8 pagesAutism Spectrum Disorder: Outcomes in Adulthood: ReviewRosa Indah KusumawardaniNo ratings yet

- tmpB80D TMPDocument8 pagestmpB80D TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- CBCL Profiles of Children and Adolescents With Asperger Syndrome - A Review and Pilot StudyDocument12 pagesCBCL Profiles of Children and Adolescents With Asperger Syndrome - A Review and Pilot StudyWildan AnrianNo ratings yet

- Impact of Ageing On Depression and Activities of Daily Livings in Normal Elderly Subjects Living in Old Age Homes and Communities of Kanpur, U.PDocument8 pagesImpact of Ageing On Depression and Activities of Daily Livings in Normal Elderly Subjects Living in Old Age Homes and Communities of Kanpur, U.PDr. Krishna N. SharmaNo ratings yet

- Autism in Adolescents and Adults MesibovDocument23 pagesAutism in Adolescents and Adults MesibovSmurfing is FunNo ratings yet

- Zuhaida Hussein Et Al. - 2021 - Loneliness and Health Outcomes Among Malaysian Older AdultsDocument8 pagesZuhaida Hussein Et Al. - 2021 - Loneliness and Health Outcomes Among Malaysian Older AdultsSyara Shazanna ZulkifliNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For Research Paper On Down SyndromeDocument8 pagesThesis Statement For Research Paper On Down Syndromekellybyersdesmoines100% (2)

- Downs Syndrome Research PaperDocument7 pagesDowns Syndrome Research Paperapi-224952015No ratings yet

- Research Essay - FinalDocument12 pagesResearch Essay - Finalapi-583983348No ratings yet

- Epidemiologia Del Adulto MayorDocument17 pagesEpidemiologia Del Adulto MayorDiana Milena Poveda Arias100% (1)

- Depression: A Treatable DiseaseDocument6 pagesDepression: A Treatable DiseaseMomina ShahNo ratings yet

- Child and Adolescent Mental DisordersDocument8 pagesChild and Adolescent Mental DisordersIsabel AntunesNo ratings yet

- Self-Stigma Experiences Among Older Adults With MeDocument10 pagesSelf-Stigma Experiences Among Older Adults With MeKlinik KitamuraNo ratings yet

- Healthy Ageing - Adults With Intellectual Disabilities: Physical Health IssuesDocument20 pagesHealthy Ageing - Adults With Intellectual Disabilities: Physical Health IssuesAntónio MartinsNo ratings yet

- (Understanding Health and Sickness Series) M.D. Patricia Ainsworth, Ph.D. Pamela C. Baker-Understanding Mental Retardation (Understanding Health and Sickness Series) - University Press of MississippiDocument212 pages(Understanding Health and Sickness Series) M.D. Patricia Ainsworth, Ph.D. Pamela C. Baker-Understanding Mental Retardation (Understanding Health and Sickness Series) - University Press of MississippiFajar YuniftiadiNo ratings yet

- Beyond Shyness - Social Anxiety PDFDocument35 pagesBeyond Shyness - Social Anxiety PDFliam_kbc100% (1)

- You Can Fix the Fat from Childhood & Other Heart Disease Risks, TooFrom EverandYou Can Fix the Fat from Childhood & Other Heart Disease Risks, TooNo ratings yet

- Autism Spectrum Disorder: A guide with 10 key points to design the most suitable strategy for your childFrom EverandAutism Spectrum Disorder: A guide with 10 key points to design the most suitable strategy for your childNo ratings yet

- Mohamad Hairie Izwan Bin RuslanDocument3 pagesMohamad Hairie Izwan Bin RuslanNor HatieykalNo ratings yet

- Grey Et Al-2015-Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual DisabilitiesDocument11 pagesGrey Et Al-2015-Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual DisabilitiesNor HatieykalNo ratings yet

- Pfeifer Et Al-2014-Child - Care, Health and DevelopmentDocument7 pagesPfeifer Et Al-2014-Child - Care, Health and DevelopmentNor HatieykalNo ratings yet

- Vogan Et Al-2014-Family RelationsDocument14 pagesVogan Et Al-2014-Family RelationsNor HatieykalNo ratings yet

- Post-School Destination-A Study of Women and Men With Intellectual Disability and The Gender-Segregated Swedish Labor MarketDocument10 pagesPost-School Destination-A Study of Women and Men With Intellectual Disability and The Gender-Segregated Swedish Labor MarketNor HatieykalNo ratings yet

- Post-School Destination-A Study of Women and Men With Intellectual Disability and The Gender-Segregated Swedish Labor MarketDocument10 pagesPost-School Destination-A Study of Women and Men With Intellectual Disability and The Gender-Segregated Swedish Labor MarketNor HatieykalNo ratings yet

- Synopsis Sing To The DawnDocument13 pagesSynopsis Sing To The DawnNoor Diana100% (1)

- Review Unit 1 - Version ADocument6 pagesReview Unit 1 - Version Aaphor1smeNo ratings yet

- Family Drama Mara Clara Remake Stars Kathryn BernardoDocument5 pagesFamily Drama Mara Clara Remake Stars Kathryn BernardoMabelle Esconde AcostaNo ratings yet

- Lessons on Kinship, Marriage, and HouseholdDocument34 pagesLessons on Kinship, Marriage, and HouseholdRica ChavezNo ratings yet

- Delhi Schools Nursery Admissions Schedule 2012 27 Dec 7AM1Document108 pagesDelhi Schools Nursery Admissions Schedule 2012 27 Dec 7AM1Vikram KumarNo ratings yet

- All Over Again PDFDocument510 pagesAll Over Again PDFXander AquinoNo ratings yet

- Spring 2010: Irresistibly Cute Nini National Symposium in Nanjing Clubs Corner Field NotebookDocument8 pagesSpring 2010: Irresistibly Cute Nini National Symposium in Nanjing Clubs Corner Field NotebookChinaCareNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Heirship: (If Never Married, Please State That Below.)Document2 pagesAffidavit of Heirship: (If Never Married, Please State That Below.)Linea Rose L. SolomonNo ratings yet

- Maternity leave benefits for unmarried gov't employeesDocument6 pagesMaternity leave benefits for unmarried gov't employeesJoy Ann DuranNo ratings yet

- Present Simple VS Present Continuous ExercisewsDocument3 pagesPresent Simple VS Present Continuous ExercisewsRodrigoChayNo ratings yet

- He Re-Imagining Blockbuster Classic Movie Film of The 80's Mga Basang Sisiw Gave Maxene Magalona A New Trade Mark of Being A VillainDocument1 pageHe Re-Imagining Blockbuster Classic Movie Film of The 80's Mga Basang Sisiw Gave Maxene Magalona A New Trade Mark of Being A VillainVon Carla AvanceñaNo ratings yet

- Peter Pan ScriptDocument7 pagesPeter Pan ScriptBrylle YabesNo ratings yet

- Family Institution Assignment 1Document30 pagesFamily Institution Assignment 1Muhammad Ali Khan100% (1)

- 4.3.1 Monohybrid N DihybridDocument5 pages4.3.1 Monohybrid N DihybridNurul Adnin Nor AzmiNo ratings yet

- Blood RelationDocument37 pagesBlood RelationPUNAM THAPANo ratings yet

- Ms. Githa Harih-WPS OfficeDocument5 pagesMs. Githa Harih-WPS OfficeAsdfghNo ratings yet

- Patricia Polacco Power Point - Childrens LitDocument22 pagesPatricia Polacco Power Point - Childrens LitKiel O'DonnellNo ratings yet

- Spelling Bee Words and SentencesDocument6 pagesSpelling Bee Words and SentencesputraNo ratings yet

- Dekalog 1 - You Shall Have No Other Gods Before MeDocument5 pagesDekalog 1 - You Shall Have No Other Gods Before MeFitzguirreNo ratings yet

- Mechanics of Heredity UtsDocument19 pagesMechanics of Heredity UtsMaridel B. BabagayNo ratings yet

- JENNY GUANAY JAZPE Reading Comprehension Family MembersDocument3 pagesJENNY GUANAY JAZPE Reading Comprehension Family MembersJENNY GUANAY JAZPENo ratings yet

- Grade 10: Idiomatic Expressions: Roles in The FamilyDocument4 pagesGrade 10: Idiomatic Expressions: Roles in The FamilySamuel Urdaneta SansoneNo ratings yet

- Soal PTK Desc ErlaDocument6 pagesSoal PTK Desc ErlaEdi WijayaNo ratings yet

- R. Compr. 5 PDFDocument6 pagesR. Compr. 5 PDFIvana Troshanska100% (1)

- Examen de Ingles 1Document1 pageExamen de Ingles 1Laura MorenoNo ratings yet

- Ekpe Lineage, Houses and FamiliesDocument2 pagesEkpe Lineage, Houses and FamiliesJustice OkedikeNo ratings yet

- FS1 Episode 4Document14 pagesFS1 Episode 4Ka Roger Man-ao PepitoNo ratings yet

- Grade 4 Coordinating Conjunctions ADocument2 pagesGrade 4 Coordinating Conjunctions ARUPANo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument10 pagesChapter 8 Multiple Choice Questionsmistermakaveli100% (1)

- E1 UoE Unit 2 PDFDocument23 pagesE1 UoE Unit 2 PDFgabriel pachecoNo ratings yet