Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Spotlight-English Language Learners

Uploaded by

api-305213050Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Spotlight-English Language Learners

Uploaded by

api-305213050Copyright:

Available Formats

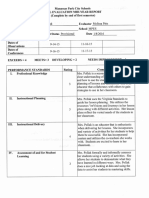

Running head: ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

English Language Learners

EDU 744: Meeting Student Literacy Challenges

Kayla Pollak

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

In todays increasingly diverse world, educators find themselves with more and more

English Language Learners in the regular classroom setting. According to the National Center

for Education Statistics, in 2013, English Language Learners made up 9.2% of the United States

Public School Population, which equates to nearly four and a half million students (NCES,

2013). Ogle and Correa-Kovtun (2010) state that Reading in the 21st century demands that all

students develop high levels of literacy (p. 532). Because of the ever-growing ESL population,

educators are striving to better understand best practices for teaching English Language Learners

in an effort to ensure that ELLs achieve success in literacy.

In the article Classroom Conversations: Opportunities to Learn for ESL Students in

Mainstream Classrooms, Williams (2001) discusses the need for classroom change in response to

the growing number of English Language Learners in the United States. Williams (2001) argues

that meeting the educational needs of the growing number of ESL students has become an

increasingly important and complex concern for educators and policy makers alike (p. 750).

Williams (2001) states that it is our job as educators to examine our teaching methods and to ask

ourselves if our instructional methods and our classroom environment are supporting English

Language Learners and promoting growth, acceptance, and success.

Williams (2001) begins by discussing some of the common struggles that English

Language Learners share, one of those struggles being language proficiency. According to

Cummins (1981), there are two types of language proficiencyinterpersonal communication

skills and cognitive academic language proficiency (as cited in Williams, 2001, p. 751).

Interpersonal communication is described as cognitively undemanding and it takes roughly

two to three years for an English Language Learner to become skilled in communicating in this

manner (Williams, 2001, p. 751). However, for English Language Learners, the main struggle

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

lies within academic language proficiency. Although ESL students might be fully capable of

exchanging greetings, expressing emotions, and following directions, it is foolish to assume that

those same students are skilled in higher order thinking skills such as comparing, classifying,

inferring, problem solving, and evaluating (Williams, 2001, p. 751). According to Collier et al.

(1987), it can take five to ten years in order for an ESL student to master proficiency in academic

language (as cited in Williams, 2001, p. 751). One reason for this apparent gap between

interpersonal proficiency and academic language proficiency is the difference between

conversational words and academic words (Williams, 2001, p. 751). In short, proficiency in

academic language takes longer because academic language words tend to be low frequency and

multi-syllable words (Williams, 2001, p. 751).

Williams (2001) goes on to provide classroom teachers with some suggestions for how to

best support ESL students. Allowing students to make connections between their native tongue

and the English language is not only a great way to achieve fluency and comprehension, but also

a wonderful way to promote acceptance and respect (Williams, 2001). Exposing English

Language Learners to visuals like anchor charts, graphic organizers, and hands on activities is

another way to best support their path to literacy (Williams, 2001, p. 751). Additionally,

Williams (2001) explains that English Language Learners need models in regards to reading with

fluency and expression. Reading aloud to your students each day is a simple and effective way

to promote language development (p. 753).

Williams (2001) focuses a lot on the classroom environment and the role it plays in an

English Language Learners literacy development. It is vital to the growth of each student that

teachers create a classroom environment that is warm, welcoming, and safe (Williams, 2001).

Williams (2001) suggests that in order to help students feel accepted and respected, teachers can

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

allow students to share their native language, encourage students to participate in classroom and

peer discussions, and continually challenge all learners, despite their level of language

proficiency (p. 754-756).

Likewise, in the article Teaching Practices for ESL Students, Curtin (2005) describes a

research study she conducted which aimed to determine effective and ineffective teaching

strategies for English Language Learners. Curtin (2005) worked closely with six middle-school

aged Spanish-speaking ESL students who were transitioning from an ESL classroom to a

mainstream classroom. During this study, Curtin (2005) observed students in all school settings,

took detailed field notes, and conducted multiple interviews with the students. According to

these ESL students, a good teacher can be defined as one who gives plenty of examples, allows

students time to understand a new concept, talks slowly and clearly, encourages flexible

grouping, and assists students during class activities (Curtin, 2005, p. 24). Unfortunately, Curtin

(2005) found that in the mainstream classrooms, the teacher did the majority of the talking,

silence was expected from all students, and there was heavy reliance on worksheets and

completed assignments from either the textbook or overhead projector (p. 24). Curtin (2005)

states that the ESL students did not like being left to work independently in classrooms where

the teacher tended to sit behind the desk and review correct answers afterwards (p. 26). The six

ESL students were very vocal with Curtin (2005) about their needs as English Language

Learners. All six students felt that in order to succeed, they needed repeated practice with

content and skills in addition to needing directions repeated more than once, in a clear and

concise manner (Curtin, 2005, p. 25).

In contrast with the mainstream classroom, when observed in the ESL classroom, the six

students were much more comfortable and relaxed (Curtin, 2005, p. 26). Instead of the teacher

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

rushing through the directions once, the ESL teacher gave step-by-step directions, repeated the

directions, and clarified any confusion before having students begin the assignment (Curtin,

2005, p. 26). In the ESL classroom, students were more involved and engaged as opposed to the

passive and reluctant behavior that was observed in the mainstream classrooms (Curtin, 2005).

Additionally, all six ESL students shared the notion that mainstream classroom teachers got mad

and frustrated when asked to clarify or repeat something (Curtin, 2005, p. 25). Because of this,

the ESL students felt uncomfortable in their mainstream classroom and began to rely on one

another for help instead of their classroom teacher (Curtin, 2005, p. 25). All of this combined led

the ESL students to conclude that the instruction they received in the ESL classroom was better

than the mainstream [classroom] (Curtin, 2005, p. 26).

Similarly to Curtin (2005), in the article Supporting English Language Learners and

Struggling Readers in Content Literacy with Partner Reading and Content, Too Routine, Ogle

and Correa-Kovtun (2010) sought to discover strategies to best help the increasing number of

English Language Learners in U.S. schools. Ogle and Correa-Kovtun (2010) came across some

key findings in their research that helped them to better understand the needs of English

Language Learners. According to Allington (2007) it is imperative that students read

independently each day from appropriate leveled texts in order to increase fluency and

comprehension (as cited in Ogle & Correa-Kovtun, 2010, p. 533). Additionally, Echevarria,

Vogt, and Short (2004) found that ESL students must be given ample opportunities to talk with

their peers about academic content, in order to increase their exposure to and use of academic

vocabulary (as cited in Ogle & Correa-Kovtun, 2010, p. 533). Moreover, Almasi (2008) argues

that learning is enhanced when students ask and answer their own questions (as cited in Ogle

& Correa-Kovtun, 2010, p. 533). With these things in the forefront of their minds, Ogle and

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

Correa-Kovtun (2010) created a routine called Partner Reading and Content, Too (PRC2) that

encompasses proven strategies for helping English Language Learners in literacy. Essentially,

PRC2 is a routine similar to buddy or partner reading, with a few key differences. In PRC2,

student pairs have similar reading levels and interests, and the focus is on content learning

(Ogle & Correa-Kovtun, 2010, p. 535). It is important that both readers are on a similar level so

that each student feels safe and comfortable when reading aloud (Ogle and Correa-Kovtun,

2010). Additionally, unlike buddy reading, students engaged in PRC2 read two pages silently to

themselves first, before reading aloud to their buddy. This enables each reader to become

familiar with the content and academic vocabulary before having to read out loud. Each partner

is also expected to prepare a question to ask their partner, after reading their assigned page. This

promotes peer discussion with the use of academic vocabulary, which is proven to increase

learning (Almasi, 2008). The partners then switch roles, and the routine continues until the book

is finished.

The topic of best teaching strategies for English Language Learners is especially

interesting for me to research because I currently teach in a Title I school where over 50% of our

student population are English Second Language students. Williams (2001) and Curtin (2005)

both emphasize how important it is for students to make connections between their native

language and culture and their second language and culture. Curtin (2005) states that ESL

students do well academically if learning connects with both background and culture

simultaneously (p. 22). Likewise, Williams (2001) argues that in order to help students make

those connections, teachers can draw attention visually to Spanish cognates for Hispanic

students, start a classroom cognate wall or dictionary, and activate background knowledge (p.

751). I agree that these are beneficial strategies for ESL students because they have been

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

immensely helpful in my own classroom amongst my English Language Learners. When going

over the new vocabulary words for each week, my class discusses the Spanish cognates for each

word, if there are any. Often times my ESL students are very eager to use the Spanish cognate in

a sentence and then the English word in a sentence. I have found that inviting them to share their

native language with the class helps build their self-esteem and further validates the language

and culture of native Spanish speakers (Williams, 2001, p, 753).

Likewise, the articles by Williams (2001) and Ogle and Correa-Kovtun (2010) both speak

to the importance of student involvement. Williams (2001) states that In the classrooms where

students were engaged as productive learners, there was an intersection of involvement,

challenge, success, collaborative learning, and an understanding of diversity (p. 756). Williams

(2001) argues that in order to create a safe classroom environment, teachers should structure

classroom activities that allow choice and numerous opportunities for practice and interaction

(p. 756). Ogle and Correa-Kovtun (2010) seemed to have this idea of community building and

repeated practice in mind when they came up with the PRC2 routine. Ogle and Correa-Kovtun

(2010) insist that partner reading and talking is more secure and affords all students in a class

daily opportunities to talk about academic content (p. 535). In the PRC2 method, students are

encouraged to choose a book of common interest and reading level, which gives students the

opportunity and power to choose and interact with one another (Ogle & Correa-Kovtun, 2010).

Additionally, in PRC2, students [participate] in oral discussion with their partner stimulated by

the question the reader asks. This is when both partners have the opportunity to own more of

the academic vocabulary and concepts by using them in their talk (Ogle & Correa-Kovtun,

2010).

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

All three articles re-affirm my idea that in order to best help ESL students, teachers need

to help make connections to languages and cultures in addition to providing opportunities for

meaningful content based peer discussion all while creating a safe, welcoming classroom

environment. Williams (2001) states that in classrooms that are dominated by worksheets and

little instructional interaction, ESL students are at a double disadvantage. They often sit silently

in these classrooms while teachers talk and their language and academic development are

therefore impeded (p. 753). The authors of these articles have confirmed my idea that ESL

students need exposure to books, new vocabulary, and meaningful social interaction in order to

grow academically. Williams (2001), Curtin (2005), and Ogle and Correa-Kovtun (2010) have

all done a terrific job in proving that classroom environment plays a large role in an ESL

students growth in literacy. I myself am a true believer that ones environment has a big impact

on self-esteem, involvement, and performance. Williams (2001) argues that The emotional

climate of a classroom is of extreme importance in fostering academic progress (p. 755). In

order to best help the growing number of English Second Language Learners in our classrooms,

it is imperative that we, as educators, expose our students to rich texts, engaging conversations,

and comfortable environments that promote learning and growth.

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

9

References

Allington, R. L. (2007). Intervention all day long: New hope for struggling readers. Voices from

the Middle, 14(4), 7-14. Retrieved from https://une.idm.oclc.org/login?

url=http://search.proquest.com.une.idm.oclc.org/docview/213930500?accountid=12756

Almasi,J.F.(2008).UsingQuestioningStrategiestoPromoteStudents'ActiveDiscussionand

ComprehensionofContentAreaMaterial.ContentAreaReadingandLearning.

Collier, V. P.. (1987). Age and Rate of Acquisition of Second Language for Academic Purposes.

TESOL Quarterly, 21(4), 617641. http://doi.org/10.2307/3586986

Cummins,J.(1981).TheRoleofPrimaryLanguageDevelopmentinPromotingEducational

SuccessforLanguageMinorityStudents.SchoolingandLanguageMinorityStudents:A

TheoreticalFramework.

Curtin, E. (2005). Teaching practices for ESL students. Multicultural Education, 12(3), 22-27.

Retrieved from https://une.idm.oclc.org/login?

url=http://search.proquest.com.une.idm.oclc.org/docview/216512419?accountid=12756

Echevarra,J.,Vogt,M.,&Short,D.(2004).MakingcontentcomprehensibleforEnglish

learners:TheSIOPmodel(2nded.).Boston,MA:PearsonEducation.

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

10

NationalCenterforEducationStatistics(NCES)HomePage,apartoftheU.S.Departmentof

Education.(n.d.).RetrievedMay14,2016,fromhttp://nces.ed.gov/

Ogle, D., & Correa-Kovtun, A. (2010). Supporting english-language learners and struggling

readers in content literacy with the "partner reading and content, too" routine. The

Reading Teacher, 63(7), 532-542. Retrieved from https://une.idm.oclc.org/login?

url=http://search.proquest.com.une.idm.oclc.org/docview/203282606?accountid=12756

Williams, J. A. (2001). Classroom conversations: Opportunities to learn for ESL students in

mainstream classrooms. The Reading Teacher, 54(8), 750-757. Retrieved from

https://une.idm.oclc.org/login?

url=http://search.proquest.com.une.idm.oclc.org/docview/203275419?accountid=12756

You might also like

- General Kayla Pollak Resume 2019Document2 pagesGeneral Kayla Pollak Resume 2019api-305213050No ratings yet

- Informal Obs April 9Document3 pagesInformal Obs April 9api-305213050No ratings yet

- Final Project PaperDocument5 pagesFinal Project Paperapi-305213050No ratings yet

- Final Project PaperDocument5 pagesFinal Project Paperapi-305213050No ratings yet

- Choice Research On Theory and Practice EssayDocument7 pagesChoice Research On Theory and Practice Essayapi-305213050No ratings yet

- Literature Review FinalDocument9 pagesLiterature Review Finalapi-305213050No ratings yet

- Informal ObservationDocument3 pagesInformal Observationapi-305213050No ratings yet

- Acquiring Academic and Content LanguageDocument8 pagesAcquiring Academic and Content Languageapi-305213050No ratings yet

- Acquiring Academic and Content LanguageDocument8 pagesAcquiring Academic and Content Languageapi-305213050No ratings yet

- Comprehensive Assessment PlanDocument10 pagesComprehensive Assessment Planapi-305213050No ratings yet

- Context Clues Power PointDocument7 pagesContext Clues Power Pointapi-305213050No ratings yet

- Midyear Report2016Document2 pagesMidyear Report2016api-305213050No ratings yet

- Strategy ExplorationDocument6 pagesStrategy Explorationapi-305213050No ratings yet

- Vocab Context CluesDocument1 pageVocab Context Cluesapi-305213050No ratings yet

- Context Clues PracticeDocument2 pagesContext Clues Practiceapi-305213050No ratings yet

- 2016-2017 Formal Observation FormDocument4 pages2016-2017 Formal Observation Formapi-305213050No ratings yet

- End of Year Eval ReportDocument3 pagesEnd of Year Eval Reportapi-305213050No ratings yet

- 2016-2017 Observation FormDocument3 pages2016-2017 Observation Formapi-305213050No ratings yet

- Informal May2015Document3 pagesInformal May2015api-305213050No ratings yet

- Informal October 2014Document3 pagesInformal October 2014api-305213050No ratings yet

- Formal January 2015Document4 pagesFormal January 2015api-305213050No ratings yet

- Letter of RecommendationDocument1 pageLetter of Recommendationapi-305213050No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Collocations in English - Turkish PDFDocument5 pagesCollocations in English - Turkish PDFColin LewisNo ratings yet

- Effect of TBLT on Developing Speaking Skills and AttitudesDocument168 pagesEffect of TBLT on Developing Speaking Skills and AttitudesZahra SbaNo ratings yet

- Tools for Classroom AssessmentDocument13 pagesTools for Classroom AssessmentArnold Janssen TupazNo ratings yet

- Mobile-Assisted Language LearningDocument11 pagesMobile-Assisted Language LearningijdpsNo ratings yet

- Speakout Upper-Intermediate PDFDocument48 pagesSpeakout Upper-Intermediate PDFLucia DominguezNo ratings yet

- IMPROVING The STUDENTS Speaking Ablility (Ari Proposal)Document25 pagesIMPROVING The STUDENTS Speaking Ablility (Ari Proposal)Hasan Basrin Harahap80% (5)

- Guía Prográmatica Inglés I Course Description HTI: CódigoDocument17 pagesGuía Prográmatica Inglés I Course Description HTI: CódigoJackson MontoyaNo ratings yet

- Paper Communication StrategiesDocument6 pagesPaper Communication StrategiesSefira SefriadiNo ratings yet

- The Live MethodDocument127 pagesThe Live MethodDanNo ratings yet

- Kumpulan Soal Bahasa InggrisDocument16 pagesKumpulan Soal Bahasa InggrisBayu PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- ApproachesDocument2 pagesApproachesYücelinanNo ratings yet

- Program of Study Outcomes: Lesson Title/Focus Class #: Grade 1 (60 Minute Class) Course Language ArtsDocument4 pagesProgram of Study Outcomes: Lesson Title/Focus Class #: Grade 1 (60 Minute Class) Course Language Artsapi-533472774No ratings yet

- Methodological Recommendations For Summative Assessment On The Subject The English Language Grade 4Document52 pagesMethodological Recommendations For Summative Assessment On The Subject The English Language Grade 4Алтынжан Кенжекумаровна ИкласоваNo ratings yet

- Bossier Parish Recommended For Grade 2: Before The LessonDocument11 pagesBossier Parish Recommended For Grade 2: Before The LessonKristi KashtaNo ratings yet

- K To 12 Mother Tongue Curriculum Guide 1-3Document13 pagesK To 12 Mother Tongue Curriculum Guide 1-3Hari Ng Sablay100% (4)

- Word FormationDocument16 pagesWord FormationMa Xiaomeng100% (3)

- Jetset 6 Read SampleDocument2 pagesJetset 6 Read SampleAsmir DoricNo ratings yet

- Language and Thought Dependence TheoriesDocument6 pagesLanguage and Thought Dependence TheoriesRayene MedabisNo ratings yet

- Second Grade Science Matter Lesson Plan Liquids ObservationDocument3 pagesSecond Grade Science Matter Lesson Plan Liquids Observationapi-236126271No ratings yet

- Keynote Elementary Teacher's Book Tests Answer KeyDocument5 pagesKeynote Elementary Teacher's Book Tests Answer KeyRabii TahiriNo ratings yet

- Formative 1 How We OraganizeDocument3 pagesFormative 1 How We OraganizeSundas AnsariNo ratings yet

- Olimpiada Nationala de Limba Englesa Etapa Judeteana Baremul de CorectareDocument3 pagesOlimpiada Nationala de Limba Englesa Etapa Judeteana Baremul de CorectareRamona MarinucNo ratings yet

- PEL114 Business Communication Skills-1Document2 pagesPEL114 Business Communication Skills-1Shivani ChauhanNo ratings yet

- The Art of The Limerick: Teacher's NotesDocument4 pagesThe Art of The Limerick: Teacher's NotesTati Easy TalkingNo ratings yet

- German For Begginers - Part IDocument38 pagesGerman For Begginers - Part IAvram Lucia AlexandraNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Empower B1+ PDFDocument13 pagesUnit 1 Empower B1+ PDFDominika100% (1)

- IGCSE First Language ArabicDocument14 pagesIGCSE First Language ArabicALIALIALA0% (1)

- (GR) Igcse Textbook Answers Section 2 (Document81 pages(GR) Igcse Textbook Answers Section 2 (Ilaxa MammadzadeNo ratings yet

- B1 Video Extra Worksheets and Teachers NotesDocument3 pagesB1 Video Extra Worksheets and Teachers NotesMarcelo Aguirre0% (1)