Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sexualidad Adolescente3

Uploaded by

fl4u63rtOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sexualidad Adolescente3

Uploaded by

fl4u63rtCopyright:

Available Formats

www.rhm-elsevier.

com

2009 Reproductive Health Matters.

All rights reserved.

Reproductive Health Matters 2009;17(34):8898

0968-8080/09 $ see front matter

PII: S 0 9 6 8 - 8 0 8 0 ( 0 9 ) 3 4 4 7 1 - 7

www.rhmjournal.org.uk

Teenage sexuality and rights in Chile:

from denial to punishment

Lidia Casas,a Claudia Ahumadab

a Associate Professor, Law School, Diego Portales University, Santiago, Chile.

E-mail: lidia.casas@udp.cl

b Womens Campaign Coordinator, World AIDS Campaign, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Abstract: While Chile sees itself as a country that has fully restored human rights since its return to

democratic rule in 1990, the rights of teenagers to comprehensive sexuality education are still not

being met. This paper reviews the recent history of sexuality education in Chile and related

legislation, policies and programmes. It also reports a 2008 review of the bylaws of 189 randomly

selected Chilean schools, which found that although such bylaws are mandatory, the absence of

bylaws to prevent discrimination on grounds of pregnancy, HIV and sexuality was common. In

relation to how sexual behaviour and discipline were addressed, bylaws that were non-compliant

with the law were very common. Opposition to sexuality education in schools in Chile is predicated

on the denial of teenage sexuality, and many schools punish sexual behaviour where transgression is

perceived to have taken place. While the wider Chilean society has been moving towards greater

recognition of individual autonomy and sexual diversity, this cultural shift has yet to be reflected

in the governments political agenda, in spite of good intentions. Given this state of affairs, the

Chilean polity needs to recognise its youth as having human rights, or will continue to fail in its

commitment to them. 2009 Reproductive Health Matters. All rights reserved.

Keywords: adolescents and young people, human rights, sexuality education, law and policy, Chile

HILE is a country of stark contrasts. While

progressive health care measures have

reduced maternal morbidity and mortality

rates to industrialised country levels1 and nearly

99% of births take place in a hospital setting,2

the teenage birth rate stands at almost 15% of

registered births nationally.3

Public health data show that live birth rates in

women under the age of 19 are class-sensitive,

increasing as socio-economic status decreases.4

The teenage birth rate in better-off areas of

Santiago, the capital, is less than 4% of all

births,5 similar to the rates of the Netherlands,

Norway and Sweden. The more disadvantaged

districts have rates of 1020%, as in Colombia

and the Dominican Republic, while in the most

disadvantaged areas, more than 20% of all

births are to teenage mothers, similar to African

88

countries such as Ghana.6 This reflects a significant contradiction in Chilean society: abundance alongside neglect. 7,8 Official Chilean

concern about teenage pregnancy dates back to

the 1960s, when the government created a Committee on Family Life and Sex Education (Comit

de Vida Familiar y Educacin Sexual) under the

Ministry of Education. In 1972 the government

launched a comprehensive sexuality education

programme, only to see it terminated after the

11 September 1973 military coup.9

The return to democracy in 1990 created great

expectations of a new cultural and political climate. While Chile sees itself as a country that

has fully restored human rights since 1990,

sexual and reproductive health policies, programmes and public discourse lack a consistent

human rights and gender focus.

L Casas, C Ahumada / Reproductive Health Matters 2009;17(34):8898

Methodology

This article examines some of the factors that

led to the plight facing sexuality education in

Chile today. It reviews the recent history of

sexuality education in Chile and related legislation, policies and programmes, and looks especially at their impact on adolescents rights.

We analyse official documents including laws,

motions from the Chilean Congress and documents from the Ministry of Education and

National Statistics Institute, documentation from

the World Health Organization (WHO), the United

Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), human rights

reports and academic articles, cases in 2004 and

2006 in the Court of Appeals of Santiago, a 2008

case in the Constitutional Court of Chile and

media reports from two leading newspapers,

El Mercurio and La Nacin related to sexuality

education and adolescent sexuality.

In this context, we report on a study of school

bylaws in the Santiago metropolitan region,

which we conducted in 2008,10 whose aim was

to determine whether the bylaws were in keeping with Chilean and international human rights

law, and their main strengths and limitations.

The methodology consisted of analysing the

school bylaws of a random sample of 250 schools

(22% of the total in selected educational districts).

The final sample included 189 schools regulations;

the other 61 did not make their bylaws available.

Finally, we conducted semi-structured interviews

with school heads, teachers, parents and student

representatives from seven schools.

A society with double standards

Shallat, Blofield and Shepard characterise Chile

as a society with glaring double standards.1113

Sex and sexuality are everywhere and are used

to sell beer, cars and deodorant. There is an

ongoing tension between the government, which

has attempted to take steps to support adolescent

well-being through NGO condom drives and

sexuality education initiatives, and the political

and social elites, who try to prevent these efforts

from bearing fruit. These elites consist of rightwing political figures, including parliamentarians,

municipal staff and Catholic religious leaders.

One of their first victories was in 1997, when

the Supreme Court refused to order two TV stations, including one run by the Catholic University, to carry Health Ministry spots on HIV

prevention and condom use.14 In 2003, rightwing municipal officials responded to prevention

campaigns on STIs and unwanted pregnancy by

fining NGO health workers who were distributing free condoms in Chilean summer resorts.

The local Bishop, Jorge Medina, today a Vatican

official, said of these health workers that Satan

wears many disguises.15

In 2006, two mayors challenged family planning technical norms in court on the grounds

that parents had to be informed about sexual

activity in their children, and that allowing the

prescription of emergency contraception without parental involvement interfered with the

constitutional rights of parents to educate their

children.16 These efforts resulted in the Constitutional Court banning emergency contraception from the public health care system,17 even

though the private health care system and pharmacies are still allowed to provide it. Every attempt

to integrate sexuality education in the school curriculum is fought tooth and nail by these forces.

Since 1990, however, governments in Chile have

lacked the political will to tackle issues thought

likely to cause an outcry among the opposition

and the clergy and bring about a rift in the ruling

coalition. This is not to say that no progress has

been made, but every step forward is hampered

by opposition.

Treatment of young peoples sexuality is

directly connected with the ethics, values,

mores, and attitudes towards sex prevailing

in the adult world. Teenagers not only face

restrictions on information at home, they also

depend on health care providers for sexual and

reproductive health services. Public discourse

and policy implementation show the wide

gap between unrealistic adult perceptions that

teenagers are celibate or asexual beings and

their actual needs and rights in this respect.

Even when teenage sexuality is acknowledged,

policymakers and society tend to treat it as

problematic,10,18 as if adolescents need to be

protected from themselves. For example, in

2004 the Chilean law on statutory rape was

modified with the aim of providing greater

protection for young adolescents, but was

then followed by a policy establishing a legal

obligation on health care professionals and

teachers to report any adolescent under the age

of 14 who was sexually active or sought contraceptives. This led to the refusal of services,

89

L Casas, C Ahumada / Reproductive Health Matters 2009;17(34):8898

reports to the authorities and non-compliance

with reporting, which risks sanctions.19,20

A history of sexuality education programmes

The current structure and legal framework of the

Chilean education system (public schools run

by local governments and publicly-subsidised

privately-run schools) are a legacy of the Pinochet dictatorship, governed by an Education Act

passed furtively in March 1990, in the dying

hours of the Pinochet regime. Although public

policy is under the purview of the Executive

and subject to internal political debate, law

reform requires Congressional approval.21 The

quasi-constitutional nature of the Act requires

a 4/7ths majority in both chambers of Congress

to amend; hence, all changes have been subject

to excruciatingly slow bargaining, mostly with

former Pinochet supporters and conservative

members of Congress.

As Chile ratified most international human

rights instruments, including the Convention

on the Rights of the Child, after 1990, NGOs

and academic institutions demanded policies

to address high rates of teenage pregnancy and

HIV infection. In 1991 a Commission was convened to propose major sexuality education

policy reform that was eventually adopted two

years later. The new policy provided a framework that took full account of the interests of

school principals, administrators, teachers, parents and religious officials22 but left content up

to the school community a procedural compromise designed to circumvent sharp political differences and widely conflicting views. The premise

was that since sexuality education was important

for children and young people, and families had

a primary role in imparting it, schools would

design their own programmes, with parental

involvement.22 The Commissions inability to

reach consensus also led to parents being given

the right to keep children from participating in

sexuality education. The Commissions official

statement argued that freedom of thought and

school autonomy were pivotal to public policy

on thorny issues such as sexuality:

Considering that ... incorporating a common

discourse into the school curriculum was impossible, a mechanism is required to decentralise

decision-making on issues where many diverse

norms, values and beliefs exist.22

90

JOCAS: conversations on relationships

and sexuality

Experts in the field and sexuality education

advocates regarded this result as a partial victory: at least some degree of sexuality education

would be implemented, providing a foundation

on which further action could then be taken.

However, it took two years before a pilot project,

begun with support from UNFPA, the Education

Ministry and other government agencies, began

work on JOCAS (Jornadas de Conversacin sobre

Afectividad y Sexualidad, Conversations on Relationships and Sexuality), a programme consisting

of three-day workshops for students, parents and

teachers.23 This is a massive event, where all participants are convened to work in small group

sessions lasting 90 minutes each for three days.

By the end, the school and the rest of the community should have identified the needs and

strengths of the community so as to integrate

sexuality and relationships into the school curriculum.24 After a test run in five schools in

1995,23 JOCAS were introduced more widely in

1996. A loud outcry from the Roman Catholic

hierarchy ensued, which pronounced the initiative devoid of moral values and claimed sexuality was a private issue best left to families.23

The staunchly Catholic Private Schools Federation and the government opposition also became

vocal critics.25 The Ministry held fast, hoping

that, in time, JOCAS would catch on and school

communities would start developing curricula.24

However, by 1999 less than 37% of all publiclyfunded schools had done so.23

By the end of 2000, when JOCAS was to begin

again as an joint Ministry initiative, opposition

by the Church and the Federation of Catholic

Schools resurfaced. They argued that JOCAS

heavily emphasised health criteria, not values

or mores.25 The programme was suspended after

an outcry against a talk in a school on how to

use a condom, demonstrated using a banana.26

The Minister of Education stated that education

on birth control methods was to be limited to

community health clinics and was not to take

place in schools.25 By the end of November of

2001, JOCAS were dropped by the government

as an official initiative, due to the pressure

from right-wing politicians and Catholic church

leaders. The Catholic Schools spokesperson

insisted that the sexuality education programme

only legitimised irresponsible and immature

L Casas, C Ahumada / Reproductive Health Matters 2009;17(34):8898

sex for minors, as taught under the purview of

the Ministries of Education and Health and the

Women's Bureau.25 The media reported that the

programme, intended to begin in eight municipalities, was stalled due to Church opposition.

The pilot project was later implemented, and in

spite of civil society demands for information,

it took more than five years for the outcomes

to be partially disclosed.26 These revealed that

85% of students felt they had learnt with JOCAS

and valued the open space to discuss sexuality,

while 75% of teachers noted that JOCAS strengthened their relationship with students.26

JOCAS are still remembered as a crucial experience in school integration of sexuality education. They were popular so much so that some

schools continue to apply the model to this

day. They had a nationwide outreach and were

unique, in that the dynamics rested solely on the

participants. They were perceived to be democratic and appealing to the target audiences.

Their weakness was that they were conceived

as a series of continuing events, which needed

continuity in order to meet the ongoing needs of

young people through the education system.9

School counsellors, heads and administrators

surveyed by the Ministry of Education in 2004

said that while JOCAS were productive, lack of

continuity caused momentum to be lost.27

Today, most private schools have some type

of sexuality education programme but only a

few publicly-funded schools. In addition, less

than 10% of teachers have acquired the skills

to deal with sexuality in the classroom.8 There

have been a few isolated initiatives, yet without

the necessary continuity to become established.

The torch has been passed to a variety of academic and NGO programmes, which range from

provision of contraceptive and STI services to

teenagers to promotion of abstinence.9,2830

In these circumstances, a popular phone-in

radio show heard nationwide starting in 1996

became a leading source of sexuality information for teens and young people.31 The shows

genial host succeeded where public policy had

not, getting Chilean youth to talk freely and

unreservedly about sex.

The underlying cultural shift catalysed by

a recovered democracy was also evident elsewhere. For example, the Sunday edition of a

tabloid notorious for cover photos of minimally

attired women started a section on Health and

Relationships8 that takes queries from its mostly

working-class readers, with responses provided

by prominent sexual and reproductive health

specialists. Interestingly, questions posed by

readers in the 11-19 age group fall largely

within five areas: intercourse (including anal

and oral sex), anatomy and genitalia, teenage

pregnancy, homosexuality and STIs, and masturbation. The 2004 Ministry of Education survey

revealed that over 60% of students relied on television for most of their information on sex.27

Concerned at this turn of events, Chile Unido, a

conservative agency working on family issues

and anti-abortion, successfully lobbied the tabloid owners to let them provide a conservative

viewpoint on these matters. The urgent need for

comprehensive, accurate information for teenagers persists.8 Meanwhile, the Education Ministry

had to shelve a publication for parents designed as

part of a sexuality education drive after it contents

on masturbation were deemed offensive.1

Another attempt at public policy on

sexuality education

To show that there has been progress, Shepard

used the analogy of the half-full vs. half-empty

glass to assess the JOCAS and sexuality education programme.13 While we agree, expectations

for the Lagos and Bachelet administrations in

this respect have been particularly high. However,

progress on certain issues, including sexuality,

can lag behind even under often progressive

administrations. In 2004 the Education Ministry

under Lagos convened a Commission to review

matters since 1993 when the Sex Education Policy

was passed. Members included teachers, parents,

principals, students and experts in sexuality education and other fields (including author Casas).

The Commission encountered the pent-up frustration of community groups at government failure

in this area during the previous decade. On the

other hand, conservatives warned the Commission against introducing mandatory sexuality

education in schools, arguing that the Constitution

protected freedom of education and prevented

government from changing the law or policy.

The Commission found that while the 1993

policy claimed to be grounded in human rights,

there was no mention of the rights of the child.

The 1993 policy described at length the rights

and duties of parents but neglected to emphasise

91

L Casas, C Ahumada / Reproductive Health Matters 2009;17(34):8898

the importance of adolescents ability to protect

their health and physical integrity. Since the

Convention on the Rights of the Child had been

ratified only a few years earlier, it could be

argued that the 1993 policy drafters lacked a

thorough understanding of its implications. The

new Commission noted that it was of pivotal

importance for changes in policy to be in line

with the Convention and all human rights instruments with a bearing on sexuality education.27

The procedural consensus of 1993 was based

on the premise of parental and family involvement, but little of the sort actually occurred. A

2005 Education Ministry survey found that less

than one third of private schools had invited

parents to sexuality workshops. The figure for

public schools run by local government was

less than 12%.27 Unless pressured, most schools

were clearly not open to addressing these issues.

Surveys and testimony heard by the Commission exposed the fact that most teachers lacked

the skills and educational materials required to

provide sexuality education, and that much

work and energy were needed to change this.

In 2005, the Commission, in closing, called for

respect for the diversity of views on sexuality

and the need for the government to step in where

families were not providing sufficient information or support. They proposed a five-year plan

to invite schools to develop new sexuality education curricula, starting in 2005.32 Yet, the Minister

of Education of the incoming Bachelet government lowered the priority and pulled the funding.

One activist referred to this turn of events as the

end of sexuality education in Chilean schools.33

Absence of legally mandated bylaws on

sexuality issues in schools

School bylaws, required by law, are internal codes

setting down a schools guiding principles and

rules on disciplinary matters, dress and punctuality, and generally regulate student behaviour.

Although they should be drafted in collaboration

with the entire school community, in practice they

are set by administrators with little input from

parents or students.

In 2000, legislation was passed banning discrimination against pregnant and parenting students, allowing them flexible school attendance34

and setting penalties for offending schools. It also

prohibited expelling students during the school

92

year for unpaid tuition fees and required publiclyfunded schools to recruit at least 15% of their

students from designated vulnerable groups.35

These changes were intended to comply with

the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The Education Ministry had in fact been fighting against sex and gender discrimination,

including expulsion on grounds of pregnancy,

since 1991, when it first issued guidelines regarding pregnant students.* In a 2004 Ministry of

Education survey, 90% of parents, 82% of students and 75% of teachers thought that pregnant

students should not be discriminated against.27

In 2004, an administrative regulation mandated

maternity leave before and after childbirth aimed

at helping students stay in school.36 Additionally, a law in 2000 and 2001 banned discrimination against pregnant students and HIV-positive

students,34,37 and the Ministry issued guidelines

on how to support retention of HIV-affected children and teenagers.

In 2007, UNICEF and the Education Ministry

commissioned a study of school bylaws, discrimination and due process of law10 to determine whether school bylaws were compliant

with Chilean law and human rights, how they

were drafted and applied and whether any penalties had an educational purpose. The school

bylaws we examined fell into three categories:

compliant (legal requirements were met, even if

minimally or formally), non-compliant (inconsistent with the law), or not covered at all.

While most of the bylaws appeared to be compliant, the extent of non-compliant rules and

omitted topics was significant and a matter for

*Circular 247 on pregnant students and breastfeeding

promoted the right of pregnant students to continue their

education, calling on schools to refrain from dismissing

students because of pregnancy and establishing flexible

norms regarding school attendance to enable them to

take examinations. In an emblematic case, litigated first

in the Court of Appeals of La Serena (Carabantes v. Araya,

Case 21.633, 25 December 1997), the Supreme Court

upheld a schools decision to expel a pregnant student.

However, her family brought a complaint before the InterAmerican Commission on Human Rights, which brokered

a friendly settlement. Report No. 33/02, Friendly Settlement, Petition 12046, Mnica Carabantes Galleguillos v.

Chile, March 12, 2002. At: <www1.umn.edu/humanrts//

cases/33-02.html>. Accessed 25 February 2009.

L Casas, C Ahumada / Reproductive Health Matters 2009;17(34):8898

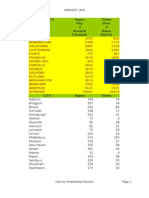

concern (Table 1). Many bylaws equivocated on

procedures for imposing penalties, while regulating other aspects to the extreme, e.g. dress code

on piercing, hair length, clothing style and colour,

and accessories.

Table 1 shows that the absence of bylaws on

pregnancy, HIV, and sexuality and discrimination

is far greater than compliant or non-compliant

bylaws. Non-compliance was also very high in

relation to how sexual behaviour and discipline

were addressed.

Some 80% of school bylaws made no mention of pregnancy or HIV and over 60% ignored

sexual behaviour. The only aspect explicitly

mentioned in compliant bylaws was pregnancy.

Awareness of pregnancy-related discrimination

issues appeared to be high, and all respondents

interviewed said that their school bylaws had

been amended as per the new law. One principal

acknowledged that although the Education

Ministry order directing schools not to expel

pregnant students dated back to 1991, in practice his schools bylaws were amended only after

2000. In all cases where the bylaws in question

were found to be compliant, their regulations

were based on maternity leave regulations in

the 2004 labour law. 36 These included: from

the seventh month of pregnancy, students are

no longer required to attend class. They should

come in once a week to pick up and return

homework and write tests, and go back to

school three months after delivery. One school

extended the maternity leave period, arguing

that it did not have the infrastructure to accommodate pregnant students and did not wish to

be held liable if something went wrong.

Sexuality was found to be regulated in ways

inconsistent with privacy rights (37.5%), banning

everything from expression of affection, where

couples meet and how they must behave, even

outside the school grounds and in their free time.

These norms, school officials said, aimed to ensure

that students did not consider schools a public

park or a living room. In mixed-sex schools,

dating was generally allowed but expressions of

great affection were not. At times, school codes

used language that was obsolete or obscure by

most young peoples standards. For example,

some schools banned behaviour contrary to

morals and decency, interpreted by some officials

as kissing and fondling and by others as having

sex on the premises. One school even banned

dating or fondling within a set radius around it.

In the 2004 Ministry of Education survey, 79%

of students and 81% of teachers thought gays

and lesbians should not be forced to keep their

sexual orientation secret.27 While most schools

had working or unwritten rules on sexual orientation, ranging from tolerance as long as there

were no public expressions of homosexuality

to the assertion that it did not happen, interviews showed that attitudes toward homosexuality

93

L Casas, C Ahumada / Reproductive Health Matters 2009;17(34):8898

were wide-ranging. While all student respondents

were aware of fellow gay and lesbian students,

principals and teachers did not always share this

awareness. A frequent student answer was that

gays and lesbians were not singled out for harassment provided they were discreet. One principal

argued that he should not be asked to accept what

the wider society had not; others were not aware

of gay or lesbian students in their schools. In our

study, students and parents recognised that students had been expelled on grounds of sexual

orientation and the school culture obliged them

to remain in the closet.

These findings illustrate the difficulties Chilean

schools face when it comes to admitting that children and teenagers are sexual beings with rights.

Chilean society has been moving towards greater

tolerance and awareness of diversity, including

with regard to sexuality. Our interviews, particularly with students, are testimony to their awareness of these matters.10 Much of the adult world,

however, has yet to see and appreciate this diversity to the same extent.

Punishment of sexuality

These findings convey a narrative of sexuality

being denied or punished in Chilean educational

settings. The absence of bylaws and non-compliant

bylaws show a failure to recognise teenagers as

holders of rights, and this translates into public

controversy whenever their sexuality comes to

the fore. At the judicial level, sexuality is viewed

through a moral lens, and is restricted solely to

adults. This was apparent in a case brought

against a Chilean television station that showed

teenagers engaging in a game of cultural striptease involving suggestive dancing and the

removal of pieces of clothing.38 The Court ruled

the segment was objectionable, because it invites

under-age individuals to naturally follow analogous behaviours that, clearly, are more appropriate for the adult world. The programme projects

the idea that sexuality is free of affection, and

invites them precociously to discover a reality

that is still unfamiliar to them, which does

not contribute to the spiritual and intellectual

development of children and youth. The latter

is an essential mission of the media, especially

television, due to its impact.38

The Chilean media have reported for years

on students being expelled from schools for

94

sexuality-related behaviour. Teenagers are discriminated against for getting pregnant or wearing attire deemed to be against moral values.

Even when cases have gone to court, students

have not always been protected from discriminatory rulings. Schools have argued that parents

and students are bound by their internal rules

and should not complain about procedures or

penalties imposed.39

Schools still tend to react with dismay whenever student sexuality surfaces. In the past few

years, several gay and lesbian students have

gone public through court cases, marches and

the media to demand that the Ministry of Education take action against discrimination in their

school. In 2005 a Brigade of Gay and Lesbian

High School students was formed seeking to

stamp out discrimination in the education

system. This collective was hosted by the Movement of Homosexual Integration and Liberation.40

Such initiatives have had varying degrees of

success. In 2004, for example, 300 students held

a rally in protest at the dismissal of two gay

students, leading to their successful reinstatement. However, many cases do not reach public

light and much remains to be done.41

The ideals of abstinence and celibacy proclaimed by most Catholic-run schools are a particularly notorious part of the culture of control

and repression. 42,43 In late 2007, the media

reported that a teenage couple, concerned about

having had unprotected sex, were suspended

after asking a school counsellor about emergency contraception. The suspension was lifted

only after the Education Ministry intervened.44

Gender discrimination was also at play in the

case of a girl unwittingly videotaped while performing oral sex on a classmate in a public park.

The video clip was uploaded to a popular website. Arguing that she had compromised the

reputation of the school and its female students,

the school asked the girl to find alternative placement but took no action against her sexual partner or the male classmates who captured the

scene on their cell phones.45

The Ministry of Education has also had to

step in in cases involving gay or lesbian students

harassed or expelled from school on sexual

orientation grounds.43 Such discrimination is

frequently reported by activists. It is not common

for students to take these cases to Court, as judges

are hard to predict. Adolescents end up voluntarily

GONZALO VELSQUEZ

L Casas, C Ahumada / Reproductive Health Matters 2009;17(34):8898

Activity on sexual diversity in an educational session conducted by Movimiento de Integracin y

Liberacin Homosexual (MOVILH), an NGO that works with gay and lesbian high school students, Chile

withdrawing from school as it was euphemistically described in our study.10

What does the future hold

2009 is an election year and for the first time

since 1990, it is far from clear whether the

centreleft coalition will be able to remain in

power. In spite of good intentions, the governments political agenda is continually being

eroded by political forces that refuse to consider

young people as sexual beings with rights.

The Rights Protection Unit of the Ministry of

Education makes important efforts to foster rights

awareness and secure students rights whenever

cases of discrimination have taken place in

schools, especially with regard to suspensions.43

However, most of these initiatives have little

impact on public policy and law. Today, the issue

is the lack of willingness to open a dialogue on

rights, gender and sexuality among young

people. The absence of an effective national

sexuality education programme is borne most

by the poorest in Chilean society because services in the private sector are not affected, only

the public sector.

The requirement of a 4/7ths majority in both

houses of Congress hampers law reform, and

conservative rhetoric has not let up. We believe

the threat of litigation will deter any government attempt to introduce mandatory sexuality

education in schools through public policy or

legal reform. These issues are present in the current debate on the Birth Control and Emergency

Contraception Bill, tabled in June 2009 by President Bachelet, to secure all methods of birth

control, including emergency contraception, in

the public health care system.46

As the presidential election in December 2009

approaches, teenage sexuality has become a

95

L Casas, C Ahumada / Reproductive Health Matters 2009;17(34):8898

bargaining chip with the opposition, who have a

candidate running high in the polls. The opposition in the Chamber of Deputies tabled an

amendment to the new bill, obliging health care

providers to inform parents or another adult when

they prescribe emergency contraception to any girl

aged 14-16, whenever they deem the teenagers

health or life to be in urgent need of protection.47

This was backed by the Executive, in hopes that

it would reduce opposition to the bill. The amendment is a regressive measure, however, compared

with the 2008 Constitutional Court decision on

emergency contraception, that upheld teenagers

right to confidential services.

When the Senate Health Committee approved

the amended bill, two supporting Senators tabled

another amendment, to establish mandatory

sexuality education programmes in schools.48

As the possibility of remaining in power is less

predictable, some politicians are willing to put

issues on the agenda that have divided the governing coalition. The pro-Pinochet UDI party has

already announced it will challenge the bill in the

Constitutional Court if it is passed by Congress.

Several UN treaty bodies have recommended

that Chile adopt laws, policies, and programmes

upholding sexual and reproductive rights.49,50

But the status quo undermines, and ultimately

violates, adolescents human rights. Unless the

Chilean polity begins to consider its youth as

holders of rights, Chile will continue to fail in

its commitment to them.

References

1. Shepard B, Casas L. Abortion

policies and practices in Chile:

ambiguities and dilemmas.

Reproductive Health Matters

2007;15(30):20210.

2. Schiappacasse V, Vidal P, Casas

L, et al. Chile: situacin de la

salud y los derechos sexuales y

reproductivos. Santiago:

Corporacin de Salud y Polticas

Sociales, Institute of

Reproductive Medicine Chile

and Department on Status of

Women, 2003.

3. National Statistics Institute.

Fecundidad en Chile. Situacin

reciente. Santiago, 2006. p.10.

At: <www.ine.cl/canales/chile_

estadistico/demografia_y_

vitales/demografia/pdf/

fecundidad.pdf>. Accessed

15 February 2009.

4. Instituto Nacional de Juventud,

Observatorio de Juventud.

5ta Encuesta Nacional de

Juventud. Santiago, 2007.

p.165. At: <www.injuv.gob.cl/

modules.php?name=Content&

pa=showpage&pid=4>.

Accessed 15 August 2009.

5. WHO Europe. Atlas of Health in

Europe. 2nd ed. Copenhagen,

2008. p.16. At: <www.euro.who.

int/Document/E91713.pdf>.

Accessed 15 August 2009.

6. WHO, UNFPA. Pregnant

96

7.

8.

9.

10.

Adolescents, Delivering on

Global Promises of Hope.

Geneva: WHO, 2006. p.8. At:

<http://whqlibdoc.who.int/

publications/2006/

9241593784_eng.pdf>.

Accessed 15 August 2009.

Reproductive Medicine Institute

of Chile. Adolescentes. At:

<www.icmer.org>. Accessed

15 August 2009.

Surez C, Navarrete D, Riffo P,

et al. Temas de la sexualidad

que preguntan adolescentes en

la prensa. Revista SOGIA 2004;

11(3):85. At: <www.cemera.cl/

sogia/pdf/2004/XI3temas.pdf>.

Accessed 30 January 2009.

Collao O, Honores CG. Hacia

una pedagoga de la sexualidad.

CIDPA: Via del Mar, 2000. p.15

At: <www.cidpa.cl/txt/

publicaciones/Haciauna.pdf>.

Accessed 3 February 2009.

Casas L, Ahumada C, Ramos L,

et al. La convivencia escolar:

componente indispensable del

derecho a la educacin. Estudio

de los Reglamentos Escolares.

Revista Justicia y Derechos

del Nio 2008;10:31740. At:

<www.unicef.cl/unicef/public/

archivos_documento/263/

Justicia_y_Derecho_10_

finalweb2008_arreglado.pdf>.

Accessed 5 February 2009.

11. Shallat L. Rites and rights:

Catholicism and contraception

in Chile. In: Private Decisions,

Public Debate: Women,

Reproduction and Population.

London: Panos, 1994. p.152.

12. Blofield M. The Politics of

Moral Sins: A Study of

Abortion and Divorce in

Catholic Chile since 1990.

Santiago: FLACSO, 2001.

13. Shepard B. Conversation and

controversies: a sexuality

education programme in

Chile. In: Running the Obstacle

Course to Sexual and

Reproductive Health: Lessons

from Latin America. Westport

CN: Praeger, 2006.

14. Cabal L, Lemaitre J, Roa M,

editors. Cuerpo y Derecho:

Legislacin y Jurisprudencia en

Amrica Latina. Bogot: Center

for Reproductive Law and Policy,

School of Law, University of Los

Andes, Temis, 2001. p.136.

15. School of Law, Diego Portales

University. Informe anual sobre

derechos humanos en Chile

2004. Hechos de 2003.

Santiago: Diego Portales

University, 2004. p.22930.

At: <www.udp.cl/derecho/

derechoshumanos/

informesddhh/informe_04/07.

pdf>. Accessed 4 February 2009.

L Casas, C Ahumada / Reproductive Health Matters 2009;17(34):8898

16. Corte de Apelaciones de

Santiago. Pablo Zalaquett y

otro con Ministra de Salud, rol

4693-2006. 10 November 2006.

17. Constitutional Tribunal, Case

740-07, 22 April 2008. At:

<www.tribunalconstitucional.

cl>. Accessed 2 February 2009.

18. Moore S, Rosenthal D.

Adolescent sexual behaviour.

In: Roker D, Coleman J, editors.

Teenage Sexuality. Health, Risk

and Education. Amsterdam:

Harwood Academic Publishers,

1998. p.35.

19. Casas L. Confidencialidad de la

informacin mdica, derechos

a la salud y consentimiento

sexual de los adolescentes.

Revista SOGIA 2005;12(3):

94111. At: <www.cemera.

cl/sogia/pdf/2005/

XII3confidencialidad.pdf>.

Accessed 17 August 2009.

20. Ahumada C. Statutory rape

law in Chile: for or against

adolescents? Journal of Politics

and Law 2009. At: <http://

ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/

jpl/issue/view/89>. Accessed

10 August 2009.

21. Constitution of Chile, Article 60.

22. Ministry of Education, Poltica

de Educacin en Sexualidad.

Para el mejoramiento de la

calidad de la Educacin.

5th ed. Santiago, 2003.

23. Guerrero E, Provoste P, Valds

A. La desigualdad olvidada:

gnero y educacin en Chile.

In: Equidad de gnero y

reformas educativas. Santiago:

Hexagrama Consultoras,

FLACSO-Buenos Aires, Instituto

de Estudios Sociales

Contemporneos Universidad

Central de Bogot, 2006. p.123.

24. Ministry of Education. Jornadas

de Afectividad y Sexualidad.

Santiago, 1999. At: <www.

mineduc.cl/biblio/documento/

jocas.pdf>. Accessed

2 February 2009.

25. Reparos catlicos a Plan

Escolar sobre Sexualidad. El

Mercurio. 23 August 2001.

At: <http://diario.elmercurio.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

cl/detalle/index.asp?id=

c65c9c04-bc3f-47d4-84b1a079f8699e5e>. Accessed

17 August 2009.

Araya E. JOCAS, El regreso?

La Nacin. 15 September 2006.

At: <www.lanacion.cl/prontus_

noticias/site/artic/20060914/

pags/20060914215658.html>.

Accessed 17 August 2009.

Ministry of Education.

Comisin de Evaluacin y

Recomendaciones sobre

Educacin Sexual. Santiago,

2005.

Cid P. La experiencia

comunitaria sobre trabajo en

sexualidad con jvenes.

Santiago: Epes, 2004.

Toledo V, Luengo X, et al.

Impacto del programa de

Educacin sexual adolescencia

Tiempo de Decisiones.

In: Molina R, Sandoval J,

Gonzlez E, editors. Salud

sexual y reproductiva en la

adolescencia. Santiago:

Editorial Mediterrneo, 2003.

Len P, Minassian M, Borgoo

R, et al. Embarazo adolescente.

Revista Pediatra Electrnica

2008;5(1):4648. (Online) At:

<www.revistapediatria.cl/

vol5num1/pdf/5_EMBARAZO%

20ADOLESCENTE.pdf>.

Accessed August 20 2009.

Barrientos J. Nueva

normatividad del

comportamiento sexual juvenil

en Chile? ltima Dcada 2006;

14(24):8197. At: <www.

scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=

sci_arttext&pid=S071822362006000100005&lng=

es&nrm=iso>. Accessed

3 February 2009.

Sols D. Sexualidad en los

colegios. At: <www.clam.org.br/

publique/cgi/cgilua.exe/sys/

start.htm?infoid=2252&tpl=

printerview&sid=51>. Accessed

20 February 2009.

Arenas L. El fin de la educacin

sexual en Chile. At: <www.

observatoriogeneroyliderazgo.

cl/index.php?option=com_

content&task=view&id=644&

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

Itemid=2>. Accessed

4 February 2009.

Law 19.688, 5 August 2000.

At: <sdi.bcn.cl/boletin/

publicadores/legislacion_

tematica/archivos/19688.pdf>.

Accessed 20 February 2009.

Law 19.979 28, October 2004.

At: <www.mineduc.cl/biblio/

documento/200708021802560.

Ley199792004.pdf>. Accessed

20 February 2009.

Ministry of Education, Decree

79, March 2004. At: <www.bcn.

cl/leyes/236569>. Accessed

20 February 2009.

Law 19.779, 2001. At: <www.

bcn.cl/leyes/pdf/actualizado/

192511.pdf>. Accessed

20 February 2009.

Court of Appeals of

Santiago, Case No. 10592-03,

19 April 2004. At: <www.

poderjudicial.cl/index2.

php?pagina1=causas/por_

rol_solo_tribunal.php?

corte=7&codigotribunal=

6051007>. Accessed

20 February 2009.

Casas L, Correa J, Wilhelm K.

Descripcin y anlisis

jurdico acerca del derecho a la

educacin y discriminacin,

Cuadernos de Anlisis

Jurdico No.12. Santiago:

Diego Portales University, 2001.

p.115230.

Movimiento de Integracin y

Liberacin Homosexual. Lanzan

Primera Brigada de Estudiantes

Gays y Lesbianas de Estudiante

Media. Santiago, 2005. At:

<www.movilh.cl/index.php?

option=com_content&task=

view&id=255>. Accessed

23 August 2009.

Informe Anual. Derechos

Humanos Minoras Sexuales

Chilenas (Hechos 2007).

Movilh. Febrero 2008, Santiago,

Chile. At: <www.movilh.

cl/documentos/VIINFORMEANUAL-ddhh-2007.

pdf>. Accessed 23 August 2009.

Human Rights Center. Informe

Anual sobre Derechos Humanos

en Chile 2008. Santiago:

97

L Casas, C Ahumada / Reproductive Health Matters 2009;17(34):8898

Universidad Diego Portales,

2008. p.242. At: <www.udp.cl/

derecho/derechoshumanos/

informesddhh/informe_08/

Derechos_ninas_ninos.pdf>.

Accessed 20 February 2009.

43. School of Law. In: Informe

Anual sobre Derechos Humanos

en Chile 2007. Hechos 2006.

Santiago: Universidad Diego

Portales, 2007. p.29395.

At: <www.udp.cl/derecho/

derechoshumanos/

informesddhh/informe_07/

minorias_sexuales.pdf>.

Accessed 20 February 2009.

44. Gutirrez N. Alumnos de

octavo bsico: suspendidos

por pedir la pldora. El

Mercurio. 27 November 2007.

At: <http://diario.elmercurio.

cl/detalle/index.asp?id=

bf0b0c98-2f94-4300-a299fca6f33795f2>. Accessed

5 February 2009.

45. Colegio La Salle saca lecciones

de un hecho que lo conmocion.

El Mercurio. 7 October 2008.

At: <http://diario.elmercurio.

cl/detalle/index.asp?id=

a8069b68-0a01-4048-a23c6bf80fe9f727>. Accessed

20 August 2009.

46. Cmara de Diputados, Boletn

6582-11, Proyecto de Ley

sobre Informacin, Orientacin

y Prestaciones en materia de

Regulacin de la Fertilidad.

30 June 2009. At: <http://sil.

senado.cl/cgi-bin/index_eleg.

pl?6582-11>. Accessed

17 August 2009.

47. Cmara de Diputados, Boletn

706-357. Formula Indicaciones

Rsum

Alors que le Chili se voit comme un pays qui a

pleinement rtabli les droits de lhomme depuis

son retour la dmocratie en 1990, les droits

des adolescents une ducation sexuelle

complte ne sont toujours pas satisfaits. Cet

article examine lhistoire de lducation sexuelle

au Chili et la lgislation, les politiques et les

programmes lis. Il fait galement tat dune

analyse du rglement dun chantillon alatoire

de 189 coles chiliennes, qui a rvl que mme

si ces textes sont obligatoires, labsence de

rglement pour prvenir la discrimination en

raison dune grossesse, du VIH et de la sexualit

tait frquente. Les rglements qui ne respectaient

pas la loi sur le traitement du comportement sexuel

et la discipline taient nombreux. Lopposition

lducation sexuelle dans les coles chiliennes se

fonde sur le refus de la sexualit adolescente, et

beaucoup dcoles punissent ce quelles jugent

tre une transgression sexuelle. Alors que la

socit chilienne plus large a volu vers une

reconnaissance accrue de lautonomie individuelle

et de la diversit sexuelle, cette orientation culturelle

ne se retrouve pas encore dans le programme

politique du Gouvernement, en dpit de bonnes

intentions. Dans cette situation, la classe politique

chilienne doit reconnatre que les adolescents ont

des droits, sous peine de trahir ses engagements

lgard de la jeunesse.

98

al Proyecto de Ley sobre

Informacin, Orientacin y

Prestaciones en materia de

Regulacin de la Fertilidad.

(Boletn N 6582-11).15

julio de 2009.

48. Meneses A. Comisin de Salud

Senado da luz verde a pldora

del da despus. La Nacin.

11 August 2009. At: <www.

lanacion.cl/prontus_noticias_

v2/site/artic/20090811/pags/

20090811191447.html>.

Accessed 17 August 2009.

49. Committee on Economic,

Social and Cultural Rights.

Concluding Observations:

Chile. 26 November 2004.

50. Committee on the Rights of

the Child. Concluding

Observations: Chile CRC/C/15/

Add.173 (3 April 2002).

Resumen

Aunque Chile se ve a s mismo como un pas

que ha restablecido plenamente los derechos

humanos desde que se reinstaur la democracia

en 1990, an no se realizan los derechos de la

adolescencia a la educacin sexual completa.

En este artculo se revisa la historia reciente

de la educacin sexual en Chile y la legislacin,

polticas y programas relacionados. Tambin se

informa sobre un estudio de 2008 de los reglamentos

de 189 escuelas chilenas seleccionadas al azar,

donde se encontr que aunque dichos reglamentos

son obligatorios, la ausencia de reglamentos para

evitar la discriminacin por motivos de embarazo,

VIH y sexualidad era comn. En cuanto a la

forma en que se trata el comportamiento sexual

y la disciplina, los reglamentos que no cumplan

con la ley eran muy comunes. La oposicin a la

educacin sexual en las escuelas de Chile se

basa en la negacin de la sexualidad de los

adolescentes, y muchas escuelas castigan el

comportamiento sexual cuando se percibe que

ha ocurrido transgresin. Aunque la sociedad

chilena en general se ha movido hacia un mayor

reconocimiento de la autonoma individual y la

diversidad sexual, an falta reflejar esta transicin

cultural en la agenda poltica del gobierno, pese a

las buenas intenciones. En vista de esta situacin, el

sistema de gobierno chileno debe reconocer que su

juventud tiene derechos humanos; de lo contrario,

continuar fracasando en su compromiso a estos.

You might also like

- Decide GDTDocument4 pagesDecide GDTfl4u63rtNo ratings yet

- Sexualidad Adolescente1Document6 pagesSexualidad Adolescente1fl4u63rtNo ratings yet

- Sexualidad Adolescente3Document11 pagesSexualidad Adolescente3fl4u63rtNo ratings yet

- GRADE For Diagnosis WorkshopDocument3 pagesGRADE For Diagnosis Workshopfl4u63rtNo ratings yet

- Sexual Intercourse Among Adolescents in Santiago, Chile: A Study of Individual and Parenting FactorsDocument9 pagesSexual Intercourse Among Adolescents in Santiago, Chile: A Study of Individual and Parenting Factorsfl4u63rtNo ratings yet

- Sexual Intercourse Among Adolescents in Santiago, Chile: A Study of Individual and Parenting FactorsDocument9 pagesSexual Intercourse Among Adolescents in Santiago, Chile: A Study of Individual and Parenting Factorsfl4u63rtNo ratings yet

- Sexual Intercourse Among Adolescents in Santiago, Chile: A Study of Individual and Parenting FactorsDocument9 pagesSexual Intercourse Among Adolescents in Santiago, Chile: A Study of Individual and Parenting Factorsfl4u63rtNo ratings yet

- Sexual Intercourse Among Adolescents in Santiago, Chile: A Study of Individual and Parenting FactorsDocument9 pagesSexual Intercourse Among Adolescents in Santiago, Chile: A Study of Individual and Parenting Factorsfl4u63rtNo ratings yet

- Global Burden of Transmitted HIV Drug Resistance.13Document12 pagesGlobal Burden of Transmitted HIV Drug Resistance.13fl4u63rtNo ratings yet

- Manual Rollei 35sDocument45 pagesManual Rollei 35sfl4u63rtNo ratings yet

- Viruses 06 02858Document22 pagesViruses 06 02858fl4u63rtNo ratings yet

- Ambrosia Body Mist PS1-73Document1 pageAmbrosia Body Mist PS1-73fl4u63rtNo ratings yet

- Authentec VPN Client Guide FinalDocument21 pagesAuthentec VPN Client Guide Finalfl4u63rtNo ratings yet

- Bergson'sDivided Line and Minkowski's PsychiatryDocument13 pagesBergson'sDivided Line and Minkowski's PsychiatryJakub TerczNo ratings yet

- Annals of Internal Medicine Apr 15, 2003 138, 8 Proquest Research LibraryDocument5 pagesAnnals of Internal Medicine Apr 15, 2003 138, 8 Proquest Research Libraryfl4u63rt100% (1)

- The Grand GrimoireDocument34 pagesThe Grand Grimoirekrauklis89% (9)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- N. TDocument10 pagesN. TShanmukha RongaliNo ratings yet

- Notes in Philippine Politics and GovernanceDocument4 pagesNotes in Philippine Politics and GovernancePretzz Sales QuiliopeNo ratings yet

- ISLP Analysis of 2013 Draft ConstitutionDocument39 pagesISLP Analysis of 2013 Draft ConstitutionWilliam DauveicokaNo ratings yet

- How Many More DaysDocument3 pagesHow Many More Daysfireheart 17100% (2)

- Hoover Digest, 2011, No. 2, SpringDocument211 pagesHoover Digest, 2011, No. 2, SpringHoover Institution100% (1)

- Jacksonian DemocracyDocument2 pagesJacksonian Democracycryan12No ratings yet

- POLGOV by AdiDocument22 pagesPOLGOV by AdiRia Bariso0% (1)

- DevolutionDocument33 pagesDevolutionVidez NdosNo ratings yet

- Written ReportDocument6 pagesWritten ReportGenevieveBeclonNo ratings yet

- F.U. Kuqe (2021) - The U.S Capitol InsurrectionDocument32 pagesF.U. Kuqe (2021) - The U.S Capitol InsurrectiondejiNo ratings yet

- 9 TH I Artem Conference VolumeDocument278 pages9 TH I Artem Conference VolumeLaura Martínez AnderoNo ratings yet

- Mandati ParlamentarDocument162 pagesMandati Parlamentar'Nadi Pilavi'No ratings yet

- Aung San Suu KyiDocument2 pagesAung San Suu KyiJiezel CostunaNo ratings yet

- Paradoxes in Plato's Doctrine of The Ideal StateDocument11 pagesParadoxes in Plato's Doctrine of The Ideal StateMaria SozopoulouNo ratings yet

- Aristide & Lavalas (PHD Thesis) PDFDocument346 pagesAristide & Lavalas (PHD Thesis) PDFRandy1313No ratings yet

- British and American Culture QuizDocument2 pagesBritish and American Culture QuizGisela Bastos0% (1)

- F-2018 Hirsch-State Theory-Vn4Document22 pagesF-2018 Hirsch-State Theory-Vn4soardjNo ratings yet

- Left-Right Political Spectrum - WikipediaDocument16 pagesLeft-Right Political Spectrum - WikipediaJohn amenNo ratings yet

- The Costs of War Americas Pyrrhic Victories - 2 PDFDocument568 pagesThe Costs of War Americas Pyrrhic Victories - 2 PDFAnonymous SCZ4uYNo ratings yet

- Speech by President Arthur Peter Mutharika at The Signing Ceremony of Four Additional Performance Contracts With Ministries at Kamuzu Palace On 16 February 2016Document10 pagesSpeech by President Arthur Peter Mutharika at The Signing Ceremony of Four Additional Performance Contracts With Ministries at Kamuzu Palace On 16 February 2016State House MalawiNo ratings yet

- Inaugural Address OF His Excellency Fidel V. Ramos President of The PhilippinesDocument8 pagesInaugural Address OF His Excellency Fidel V. Ramos President of The PhilippinesPrince Dkalm PolishedNo ratings yet

- The Arab Spring - Hand OutDocument4 pagesThe Arab Spring - Hand Outmehwish qutabNo ratings yet

- JFK The Final Solution - Red Scares White Power and Blue DeathDocument120 pagesJFK The Final Solution - Red Scares White Power and Blue DeathJohn Bevilaqua100% (3)

- The Political System in The U.K.Document11 pagesThe Political System in The U.K.Hrista Niculescu100% (2)

- Communist Manifesto PDF Full TextDocument2 pagesCommunist Manifesto PDF Full TextCourtneyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 23 The Cold WarDocument33 pagesChapter 23 The Cold Warapi-331018621No ratings yet

- Federalism and Constitutional Development in PakistanDocument10 pagesFederalism and Constitutional Development in PakistanSaadatRasheedNo ratings yet

- 1876 Vermont Vote For PresidentDocument18 pages1876 Vermont Vote For PresidentJohn MNo ratings yet

- A Return To The Figure of The Free Nordic PeasantDocument12 pagesA Return To The Figure of The Free Nordic Peasantcaiofelipe100% (1)