Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ombudsman Has No Jurisdiction Over Criminal Charges Against Judges

Uploaded by

mrrrkkkOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ombudsman Has No Jurisdiction Over Criminal Charges Against Judges

Uploaded by

mrrrkkkCopyright:

Available Formats

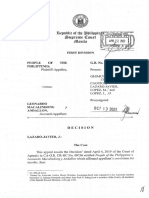

FIRST DIVISION

[G.R. No. 137354. July 6, 2000]

SALVADOR M. DE VERA, petitioner, vs. HON. BENJAMIN V. PELAYO,

Presiding Judge, Branch 168, Regional Trial Court, Pasig City; and

EVALUATION AND INVESTIGATION BUREAU, OFFICE OF THE

OMBUDSMAN, respondents.

DECISION

PARDO, J.:

"It is said that a little learning is a dangerous thing; and he who

acts as his own lawyer has a fool for a client."

In Re: Joaquin

Borromeo

241 SCRA 408

(1995)

The case is a petition for certiorari and mandamus[1] assailing the

Evaluation Report of the Evaluation and Investigation Office, Office of the

Ombudsman, dated October 2, 1998 referring petitioners complaint to the

Supreme Court and its Memorandum, dated January 4, 1999, [2] denying

petitioners motion for reconsideration.

We state the relevant facts.

Petitioner is not a member of the bar. Possessing some awareness of legal

principles and procedures, he represents himself in this petition.

On August 28, 1996, petitioner instituted with the Regional Trial Court,

Pasig City a special civil action for certiorari, prohibition and mandamus to

enjoin the municipal trial court from proceeding with a complaint for

ejectment against petitioner.[3] When the Judge originally assigned to the

case inhibited himself, the case was re-raffled to respondent Judge

Benjamin V. Pelayo.[4]

On July 9, 1998, the trial court denied petitioners application for a

temporary restraining order. Petitioner moved for reconsideration. The court

denied the same on September 1, 1998. [5]

On September 23, 1998, petitioner filed with the Office of the Ombudsman

an affidavit-complaint[6] against Judge Pelayo, accusing him of violating

Articles 206[7] and 207[8]of the Revised Penal Code and Republic Act No.

3019.[9]

On October 2, 1998, Associate Graft Investigation Officer, Erlinda S. Rojas

submitted an Evaluation Report recommending referral of petitioners

complaint to the Supreme Court. Assistant Ombudsman Abelardo L.

Apotadera approved the recommendation.[10] We quote the decretal portion

of the report:[11]

"FOREGOING CONSIDERED, and in accordance with the

ruling in Maceda vs. Vasquez, 221 SCRA 464, it is respectfully

recommended that the instant complaint be referred to the

Supreme Court for appropriate action. The same is hereby

considered CLOSED and TERMINATED insofar as this Office is

concerned."

On October 13, 1998, the Office of the Ombudsman referred the case to

the Court Administrator, Supreme Court.[12]

On November 6, 1998, petitioner moved for the reconsideration of the

Evaluation Report.

On January 4, 1999, the Ombudsman denied the motion for

reconsideration.[13]

Hence, this petition.[14]

The issue is whether or not the Ombudsman has jurisdiction to entertain

criminal charges filed against a judge of the regional trial court in

connection with his handling of cases before the court.

Petitioner criticizes the jurisprudence[15] cited by the Office of the

Ombudsman as erroneous and not applicable to his complaint. He insists

that since his complaint involved a criminal charge against a judge, it was

within the authority of the Ombudsman not the Supreme Court to resolve

whether a crime was committed and the judge prosecuted therefor.

The petition can not succeed.

We find no grave abuse of discretion committed by the Ombudsman. The

Ombudsman did not exercise his power in an arbitrary or despotic manner

by reason of passion, prejudice or personal hostility.[16] There was no

evasion of positive duty. Neither was there a virtual refusal to perform the

duty enjoined by law.[17]

We agree with the Solicitor General that the Ombudsman committed no

grave abuse of discretion warranting the writs prayed for.[18] The issues

have been settled in the case of In Re: Joaquin Borromeo.[19] There, we laid

down the rule that before a civil or criminal action against a judge for a

violation of Art. 204 and 205 (knowingly rendering an unjust judgment or

order) can be entertained, there must first be "a final and authoritative

judicial declaration" that the decision or order in question is indeed "unjust."

The pronouncement may result from either:[20]

(a).....an action of certiorari or prohibition in a higher court

impugning the validity of the judgment; or

(b).....an administrative proceeding in the Supreme Court

against the judge precisely for promulgating an unjust judgment

or order.

Likewise, the determination of whether a judge has maliciously delayed the

disposition of the case is also an exclusive judicial function. [21]

"To repeat, no other entity or official of the Government, not the

prosecution or investigation service of any other branch, not

any functionary thereof, has competence to review a judicial

order or decision -- whether final and executory or not -- and

pronounce it erroneous so as to lay the basis for a criminal or

administrative complaint for rendering an unjust judgment or

order. That prerogative belongs to the courts

alone (underscoring ours)."[22]

This having been said, we find that the Ombudsman acted in accordance

with law and jurisprudence when he referred the cases against Judge

Pelayo to the Supreme Court for appropriate action.

WHEREFORE, there being no grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack

or excess of jurisdiction committed by the respondent, we DISMISS the

petition and AFFIRM the Evaluation Report of the Evaluation and

Investigation Office, Office of the Ombudsman dated October 2, 1998 and

its memorandum, dated January 4, 1999, in toto.

No costs.

SO ORDERED.

Davide, Jr., C.J., (Chairman), Puno, Kapunan, and Ynares-Santiago,

JJ., concur.

[1]

Under Rule 65 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure.

[2]

In CPL No. 98 - 2911.

[3]

In SCA No. 1151, Sps. De Vera v. Hon. Quijano, Presiding Judge MTC Taguig, a

petition forcertiorari, prohibition and mandamus with Temporary Restraining

Order to enjoin MTC, Branch 74 from proceeding with a complaint for ejectment

against them.

[4]

Branch 168, Regional Trial Court, Pasig City. He retired on March 31, 1999.

[5]

Rollo, p. 98.

[6]

Rollo, pp. 26-33.

[7]

Knowingly rendering an unjust interlocutory order.

[8]

Malicious delay in the administration of justice.

[9]

Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act.

[10]

Rollo, pp. 51-52.

[11]

Rollo, p. 52.

[12]

Rollo, p. 53.

[13]

Roland B. Galvan, Assistant Graft Investigative Officer I submitted a

memorandum ("Comment and Recommendation") recommending denial of

petitioners motion for reconsideration. Angel C. Mayoralgo, Jr., Director of the

Evaluation and Preliminary Investigation Bureau of the Office of the Ombudsman

recommended approval. The recommendation was approved by Abelardo L.

Aportadera, Assistant Ombudsman, EIO (Rollo, pp. 61-62)

[14]

Petition filed on February 17, 1999, Rollo, pp. 3-25. On January 24, 2000, we

gave due course to the petition (Rollo, pp. 108-109)

[15]

Maceda v. Vasquez, 221 SCRA 464 (1993) and Dolalas v. Office of the

Ombudsman-Mindanao, 265 SCRA 818 (1996)

[16]

Arsenio P. Reyes, Jr. v. Court of Appeals, G. R. No. 136478, March 27, 2000;

Director Guillermo Domondon v. Sandiganbayan, G. R. No. 129904, March 16,

2000.

[17]

Barangay Blue Ridge "A" of Quezon City v. Court of Appeals, G. R. No. 11854,

November 24, 1999.

[18]

Memorandum filed by Solicitor General Ricardo P. Galvez, Assistant Solicitor

General Antonio L. Villamor and Solicitor Derek R. Puertollano (Rollo, pp. 140143.)

[19]

241 SCRA 408, 460 (1995)

[20]

Ibid, at 464.

[21]

In Re: Borromeo, supra, at 461.

[22]

Ibid.

You might also like

- 7.de Vera v. Pelayo 335 SCRA 281 PDFDocument5 pages7.de Vera v. Pelayo 335 SCRA 281 PDFaspiringlawyer12340% (1)

- Spouses Rafols v. Barrios JRDocument6 pagesSpouses Rafols v. Barrios JRLeaNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics 1Document1 pageLegal Ethics 1Kris TinNo ratings yet

- 23 Balaoing Vs CalderonDocument8 pages23 Balaoing Vs CalderonEditha Santos Abalos CastilloNo ratings yet

- DE VERA vs PELAYO case on Ombudsman jurisdiction over judgesDocument2 pagesDE VERA vs PELAYO case on Ombudsman jurisdiction over judgesLudica OjaNo ratings yet

- Ynares-Santiago (Chairperson), Chico-Nazario, Velasco, Jr. Petition Denied, Judgment and Resolution AffirmedDocument9 pagesYnares-Santiago (Chairperson), Chico-Nazario, Velasco, Jr. Petition Denied, Judgment and Resolution AffirmedApple BottomNo ratings yet

- Bantolo vs. CastillionDocument5 pagesBantolo vs. CastillionJona MayNo ratings yet

- Puyat vs. Zabarte 352 SCRA 738Document20 pagesPuyat vs. Zabarte 352 SCRA 738BernsNo ratings yet

- Adm Case No. 2474Document7 pagesAdm Case No. 2474Christie Joy BuctonNo ratings yet

- Day 7 - Millado DanDocument13 pagesDay 7 - Millado DanDan R. MilladoNo ratings yet

- LUZVIMINDA C. COMIA, Complainant, vs. JUDGE CONRADO R. ANTONA, RespondentDocument16 pagesLUZVIMINDA C. COMIA, Complainant, vs. JUDGE CONRADO R. ANTONA, RespondentEunice SagunNo ratings yet

- Chua vs. People of The Philippines, G.R. No. 195248, November 22, 2017Document9 pagesChua vs. People of The Philippines, G.R. No. 195248, November 22, 2017altheavergaraNo ratings yet

- Gachalan Promotions vs. NaldozaDocument5 pagesGachalan Promotions vs. NaldozaReth GuevarraNo ratings yet

- 5 Eduardo R Balaoing Vs Leopoldo Calderon PDFDocument6 pages5 Eduardo R Balaoing Vs Leopoldo Calderon PDFNunugom SonNo ratings yet

- CHARLES BERNARD H. REYES Doing Business Under The Name and Style CBH REYES ARCHITECTS, v. ANTONIO YULO BALDEDocument3 pagesCHARLES BERNARD H. REYES Doing Business Under The Name and Style CBH REYES ARCHITECTS, v. ANTONIO YULO BALDEAlyssa TorioNo ratings yet

- Delta Ventures vs. CabatoDocument5 pagesDelta Ventures vs. CabatoLisa BautistaNo ratings yet

- Macias Vs SeldaDocument3 pagesMacias Vs SeldaNelia Mae S. VillenaNo ratings yet

- Go V Clerk of Court VillanuevaDocument13 pagesGo V Clerk of Court VillanuevafranceheartNo ratings yet

- Felongco Vs DictadoDocument12 pagesFelongco Vs DictadoJm ReyesNo ratings yet

- CASES Not PrintedDocument197 pagesCASES Not PrintedMykee AlonzoNo ratings yet

- A.C. No. 4017 September 29, 1999 Gatchalian Promotions Talents Pool, INC., Complainant, ATTY. PRIMO R. NALDOZA, RespondentDocument4 pagesA.C. No. 4017 September 29, 1999 Gatchalian Promotions Talents Pool, INC., Complainant, ATTY. PRIMO R. NALDOZA, RespondentaguyinthecloudsNo ratings yet

- Hilario vs. People Full Text CaseDocument20 pagesHilario vs. People Full Text CaseTeam2KissNo ratings yet

- Ethics 3Document12 pagesEthics 3ConnieAllanaMacapagaoNo ratings yet

- Abrogar Case, (Legal Ethics)Document5 pagesAbrogar Case, (Legal Ethics)Elmer UrmatamNo ratings yet

- Court upholds dismissal of appeal in debt collection caseDocument23 pagesCourt upholds dismissal of appeal in debt collection caseharuhime08No ratings yet

- Supreme Court fines judge for denying due processDocument7 pagesSupreme Court fines judge for denying due processLA AINo ratings yet

- Marquez v. DesiertoDocument9 pagesMarquez v. DesiertoIan Timothy SarmientoNo ratings yet

- Last Cases To PrintDocument7 pagesLast Cases To PrintLotionmatic LeeNo ratings yet

- 8 - Macia V SeldaDocument4 pages8 - Macia V SeldaOdette JumaoasNo ratings yet

- Candido AmilDocument3 pagesCandido AmilInnah Agito-RamosNo ratings yet

- 03 Siy Lim V Carmelito MontanoDocument6 pages03 Siy Lim V Carmelito MontanoErix LualhatiNo ratings yet

- Annulment of Judgment of Court of AppealsDocument96 pagesAnnulment of Judgment of Court of Appealslucio orio tan, jr.No ratings yet

- RTC Judge Falsified Certificates, Delayed CasesDocument7 pagesRTC Judge Falsified Certificates, Delayed CasesIra CanonizadoNo ratings yet

- 3 Oribello Vs CADocument12 pages3 Oribello Vs CAIvan Montealegre ConchasNo ratings yet

- SEAFDEC Researcher's Appeal of Estafa ConvictionDocument5 pagesSEAFDEC Researcher's Appeal of Estafa ConvictionKeyan MotolNo ratings yet

- Case 4. Republic v. Sereno, G.R. No. 237428, June 19, 2018Document23 pagesCase 4. Republic v. Sereno, G.R. No. 237428, June 19, 2018Bryan delimaNo ratings yet

- Go v. Villanueva, Jr.Document10 pagesGo v. Villanueva, Jr.MICHAEL P. PIMENTELNo ratings yet

- Uganda Land Title Error AppealDocument9 pagesUganda Land Title Error AppealReal TrekstarNo ratings yet

- F. People v. Lo Ho Wing, G.R. No. 88017, 21 January 1991Document9 pagesF. People v. Lo Ho Wing, G.R. No. 88017, 21 January 1991JMae MagatNo ratings yet

- Ombudsman Ordered to Dismiss Long-Pending CasesDocument2 pagesOmbudsman Ordered to Dismiss Long-Pending CasesLuz Celine CabadingNo ratings yet

- Cases in Legal EthicsDocument97 pagesCases in Legal EthicsAnonymous 1lYUUy5TNo ratings yet

- Abay vs. MontesinoDocument4 pagesAbay vs. MontesinoYen MoradaNo ratings yet

- Petitioners Vs Vs Respondent The Solicitor General Danilo C. CunananDocument4 pagesPetitioners Vs Vs Respondent The Solicitor General Danilo C. CunananDarla GreyNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 84719 Estafa Case ReviewDocument6 pagesG.R. No. 84719 Estafa Case ReviewPlacido PenitenteNo ratings yet

- Office of The Ombudsman v. Heirs of Vda. De-VenturaDocument7 pagesOffice of The Ombudsman v. Heirs of Vda. De-VenturaCarrotman IsintheHouseNo ratings yet

- GSIS V PacquingDocument7 pagesGSIS V PacquingMaya Angelique JajallaNo ratings yet

- Marquez V DesiertoDocument10 pagesMarquez V DesiertoJoyce KevienNo ratings yet

- 7.1 Prieto Vs CorpuzDocument6 pages7.1 Prieto Vs CorpuzSugar ReeNo ratings yet

- Atty. David Ompoc v. Judge Norito TorresDocument2 pagesAtty. David Ompoc v. Judge Norito TorresJay-Em Daguio100% (3)

- Reyes Vs ChiongDocument6 pagesReyes Vs ChiongRonaldNo ratings yet

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondent Balagtas P. Ilagan The Solicitor GeneralDocument3 pagesPetitioner vs. vs. Respondent Balagtas P. Ilagan The Solicitor GeneralCeasar Neil SaysonNo ratings yet

- Pagdanganan Vs Atty PlataDocument6 pagesPagdanganan Vs Atty PlataPLM Law 2021 Block 9No ratings yet

- Philippine Court Motion Declare Defendant DefaultDocument4 pagesPhilippine Court Motion Declare Defendant DefaultGilianne Kathryn Layco Gantuangco-CabilingNo ratings yet

- 9 Barbero vs. DumlaoDocument13 pages9 Barbero vs. DumlaoJantzenNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Ruling on Attorney Misconduct ComplaintsDocument8 pagesSupreme Court Ruling on Attorney Misconduct ComplaintsJessica Jimenez SaltingNo ratings yet

- 4 Puyat Vs ZabarteDocument9 pages4 Puyat Vs ZabarteAnneNo ratings yet

- The Book of Writs - With Sample Writs of Quo Warranto, Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Certiorari, and ProhibitionFrom EverandThe Book of Writs - With Sample Writs of Quo Warranto, Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Certiorari, and ProhibitionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (9)

- Bar Review Companion: Remedial Law: Anvil Law Books Series, #2From EverandBar Review Companion: Remedial Law: Anvil Law Books Series, #2Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- An Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeFrom EverandAn Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeNo ratings yet

- PUP CL RECAP Application FormDocument5 pagesPUP CL RECAP Application Formmrrrkkk100% (1)

- Valid TORDocument1 pageValid TORJJ PernitezNo ratings yet

- Web ViewDocument5 pagesWeb ViewmrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- Graduate Studies - MpaDocument4 pagesGraduate Studies - MpamrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Book 1 RVSDDocument10 pagesCriminal Law Book 1 RVSDmrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- FMDS - UP Open University4Document3 pagesFMDS - UP Open University4mrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- DipPM MPA Course Description PDFDocument4 pagesDipPM MPA Course Description PDFmrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- PUP CL RECAP Application FormDocument5 pagesPUP CL RECAP Application Formmrrrkkk100% (1)

- FMDS - UP Open University5Document3 pagesFMDS - UP Open University5mrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- (G.R. No. 132518. March 28, 2000) : Decision Kapunan, J.Document14 pages(G.R. No. 132518. March 28, 2000) : Decision Kapunan, J.mrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- FMDS - UP Open University3Document3 pagesFMDS - UP Open University3mrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- RTC Tagaytay judges and staff face rapsDocument23 pagesRTC Tagaytay judges and staff face rapsmrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- GRADUATE Admission Requirements 2Document1 pageGRADUATE Admission Requirements 2mrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- Respect Courts JudgesDocument25 pagesRespect Courts JudgesmrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- Documentary Requirements for UPOU ApplicationDocument2 pagesDocumentary Requirements for UPOU ApplicationmrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- Graduate Studies - MpaDocument4 pagesGraduate Studies - MpamrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- Master of Public ManagementDocument4 pagesMaster of Public ManagementmrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- Ombudsman Has No Jurisdiction Over Criminal Charges Against JudgesDocument4 pagesOmbudsman Has No Jurisdiction Over Criminal Charges Against JudgesmrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- Master Course Description and Syllabus For Email Inquiries and StudentsDocument10 pagesMaster Course Description and Syllabus For Email Inquiries and StudentsmrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- Directories FMDS Comprehensive Exam Date Schedule Second Sem (AY 16 17)Document3 pagesDirectories FMDS Comprehensive Exam Date Schedule Second Sem (AY 16 17)mrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- Common Law Civil Law TraditionsDocument11 pagesCommon Law Civil Law Traditionsmohsinemahraj100% (3)

- A.C. No. 7922 October 1, 2013 MARY ANN T.MATTUS, Complainant, ATTY. ALBERT T. VILLASECA, RespondentDocument7 pagesA.C. No. 7922 October 1, 2013 MARY ANN T.MATTUS, Complainant, ATTY. ALBERT T. VILLASECA, RespondentmrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- THE BOH WAY - v1Document13 pagesTHE BOH WAY - v1mrrrkkk100% (2)

- DipPM MPA Course Description PDFDocument4 pagesDipPM MPA Course Description PDFmrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- CabalitvcoaDocument19 pagesCabalitvcoamrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- BPI Savings Account No. 3149-0491-25Document7 pagesBPI Savings Account No. 3149-0491-25mrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- BPI Savings Account No. 3149-0491-25Document7 pagesBPI Savings Account No. 3149-0491-25mrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- Common Law Civil Law TraditionsDocument11 pagesCommon Law Civil Law Traditionsmohsinemahraj100% (3)

- Be RadioDocument6 pagesBe RadiomrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- BPI Savings Account No. 3149-0491-25Document7 pagesBPI Savings Account No. 3149-0491-25mrrrkkkNo ratings yet

- Case Study: Goddard Systems IncDocument2 pagesCase Study: Goddard Systems Inckhan shadabNo ratings yet

- Background To Industrial RelationsDocument38 pagesBackground To Industrial RelationsBrand GireeNo ratings yet

- GPSA Engineering Data Book 14th Edition: Revision Date Reason (S) For RevisionDocument15 pagesGPSA Engineering Data Book 14th Edition: Revision Date Reason (S) For RevisionAsad KhanNo ratings yet

- Anglotopia's Dictionary of British English - 2nd Edition - ExcerptDocument15 pagesAnglotopia's Dictionary of British English - 2nd Edition - ExcerptJonathan ThomasNo ratings yet

- People vs. MacalindongDocument16 pagesPeople vs. Macalindongbadi jamNo ratings yet

- ISL201 MidTerm Latest Solved Paper 1Document6 pagesISL201 MidTerm Latest Solved Paper 1Kamran Muhammad75% (4)

- Engineer in SocietyDocument17 pagesEngineer in SocietyToyinNo ratings yet

- Karam Singh v. State of HPDocument8 pagesKaram Singh v. State of HPmansha sidhuNo ratings yet

- Business Roundtable Statement On The Purpose of A Corporation With SignaturesDocument12 pagesBusiness Roundtable Statement On The Purpose of A Corporation With SignaturesMadeleineNo ratings yet

- Assignment For Week 10 - 2022Document7 pagesAssignment For Week 10 - 2022Rajveer deepNo ratings yet

- Thursday, May 29, 2014 EditionDocument20 pagesThursday, May 29, 2014 EditionFrontPageAfricaNo ratings yet

- RPH NowDocument2 pagesRPH NowBilling ZamboecozoneNo ratings yet

- Master Resell RightsDocument2 pagesMaster Resell RightsMarco Aurelio lucaNo ratings yet

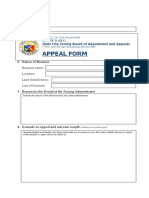

- Appeal or Petition Form for Iloilo City Zoning BoardDocument6 pagesAppeal or Petition Form for Iloilo City Zoning BoardRudiver Jungco JrNo ratings yet

- VaYeira Shem MishmuelDocument5 pagesVaYeira Shem MishmuelPracticleSpiritNo ratings yet

- Electromagnetic Compatibility: Unit-2: CablingDocument27 pagesElectromagnetic Compatibility: Unit-2: CablingShiva Prasad MNo ratings yet

- Guide to Analyzing and Interpreting Financial InformationDocument80 pagesGuide to Analyzing and Interpreting Financial InformationBoogy Grim100% (1)

- Lodge Officers Duties of The LodgeDocument2 pagesLodge Officers Duties of The LodgeKeny DrescherNo ratings yet

- Hospital Controlled Drug ProceduresDocument3 pagesHospital Controlled Drug ProceduresvaniyaNo ratings yet

- CHR Report 2017 IP Nat InquiryDocument30 pagesCHR Report 2017 IP Nat InquiryLeo Archival ImperialNo ratings yet

- Get a new Creo license for student editionDocument3 pagesGet a new Creo license for student editionGo IbiboNo ratings yet

- Internship Allowance Claim Form - Latest - 2Document1 pageInternship Allowance Claim Form - Latest - 2Rashidah MahmudNo ratings yet

- Biblical Commentary On The Prophecies of Isaiah FR PDFDocument267 pagesBiblical Commentary On The Prophecies of Isaiah FR PDFAbigailGuido89No ratings yet

- Estate Tax Mulitiple ChoiceDocument7 pagesEstate Tax Mulitiple ChoiceMina ValenciaNo ratings yet

- UCR2612 Criminal Law I 2020Document4 pagesUCR2612 Criminal Law I 2020NBT OONo ratings yet

- Toefl Ibt BulletinDocument46 pagesToefl Ibt BulletinAshley BastideNo ratings yet

- US Court of Appeals Ninth Circuit Ruling on Admissibility of Expert Testimony in Bendectin Birth Defects CaseDocument10 pagesUS Court of Appeals Ninth Circuit Ruling on Admissibility of Expert Testimony in Bendectin Birth Defects CaseGioNo ratings yet

- Cir Vs Campos RuedaDocument4 pagesCir Vs Campos RuedaAljay LabugaNo ratings yet

- InMode 20-F 2021Document210 pagesInMode 20-F 2021brandon rodriguezNo ratings yet

- CipherTrust Manager - Hands-On - Overview and Basic ConfigurationDocument25 pagesCipherTrust Manager - Hands-On - Overview and Basic ConfigurationbertinNo ratings yet