Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rural Sociology at The Crossroads : Richard S. Krarmich

Uploaded by

Maria BrignardelloOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rural Sociology at The Crossroads : Richard S. Krarmich

Uploaded by

Maria BrignardelloCopyright:

Available Formats

p

). 2008, pp. 1-21

C>>pyTighi 201)8 by rhr Rural .Sociological Socieiy

Presidential Address

Rural Sociology at the Crossroads*

Richard S. Krarmich

Utah Stale University

A complex array of socio-historical, demogi-aphic. and organizational factors have combined in recent years to threaten both the current

status of and future prospects for the discipline of rural sociology, and for

the Rural Sociological Society (RSS). This papei' examines the somewhat

problematic recent trajectories of the RSS as a professional organization and

of rural sociology more generally and notes a degree of disciplinary and

organizational inertia that have limited the pursuit of new directions. It also

presents a discussion of selected factors that have contiibuted to these

concerns, including both "external" factors that are largely beyond the

organizational reach of RSS and "internal" factors that aie more directly

linked to organizational characteristics and actions. Drawing upon the

distinctions between "red ocean" and "blue ocean" strategies outlined by

market strategists Kim and Mauborgne, the discussion then shifts to a focus

on action alternatives that, if pursued, could help to create an expanded set

of opportunities and a brighter futtire for niral sociology, and for the Rural

Sociological Society.

ABSTRACT

Presidential addresses to profes.sional organizations typically follow one

of two primary paths. The first of these involves presentation of a

synthetic overview and extension of core themes and questions around

which the author's own research interests and contributions are

centered. A second, somewhat less common path involves a foctis on

the "state of the discipline," and on major trends and directions that

affect the status and future of a particular field of study. After spending

most of a career writing on topics revolving around natural resources

and community change, I initially set out on the first of these paths and

worked to prepare an address linked to those themes. However, in the

end, those topics were left for another day in order to address more

pressing concerns that confront our discipline and our professional

organization.

This paper is to a large extent foctised on the socio-historical,

demographic, and organizational factors that in combination threaten

the current status of and future prospects for rural sociology, and the

This paper was improved by commenmand reactions provided by numerous colleagues

following its initial presentation at the 2007 annual meeting of the Rural Sociological

Society, and by more formal reviewsprovidedby two past-Presidents of RSS. Please direct all

correspondence to Richard S. Krannich, Department of Sociology, Social Work and

Anthropology. Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322-0720, richard.krannich@usu.edu.

Rural Sociology, Vol. 73, No. 1, March 2008

Rural Sociological Society. At the same time, portions of the paper are

unabashedly opinionated, and iinapologetically prescriptive. The

challenges that confront rural sociology are substantial, and they

require immediate attention. For that reason, this paper is as much as

anything else a call to action.

The discussion that follows is focused initially on the current status

and somewhat problematic trajectories of RSS as a professional

organization and of rural sociology more generally. Attention is then

directed to an analysis of selected factors that have contributed to the

challenges and vttlnerabilities that now confront us. The paper ends

with a discussion of strategies that might be pursued by the Rural

Sociological Society to enhance the future prospects of both the

organization and the discipline.

Where We AreAnd How We Got There

After several decades of what Bill Ftinn (1982) referred to 25 years ago

as "self-flagellation" and Bill Friedland (1982) called "continuous

...and relende.ss introspection," both the discipline of rtiral sociology

and the Rural Sociological Society (RSS) appear to have made only

Hmited progress in adapting to changing circumstances that affect both

the institutional contexts in which most of tis are employed and the

rural people, communities, and societies that are the focal points of our

work. As an organization, RSS has been slow to change and reluctant to

pursue the kind of extended and intensive strategic planning needed to

establish new directions. These circutnstances have brought the field of

rural sociology and the RSS to a critical crossroads. While I do not want

to be alarmist, I have no douht that "business as usual" cannot

continue any longerthe time to act is upon us. Our decisions about

future directions and about strategies for accomplishing organizational

change will determine whether rural sociology and the Rtiral

Sociological Society will be sustained, or whether our discipline and

our professional organization will continue to lose ground and

gradttally fade into relative obscurity.

Membership numbers represent one key indicator of organizational

health, vitality, and capacity to exert infltience and effect change.

Unfortunately, a review of trends in RSS membership over the past

decade provides very litde in the way of good news. Between 1988 and

1997 the organization's total membership exhibited short-term spurts

of both growth and decline, ranging from a low of 893 members in 1993

to a high of 1101 members in 1997. However, over the past decade the

trend has been more uniformly one of membership stagnation and

Rural Sociology at the Crossroads Krannich

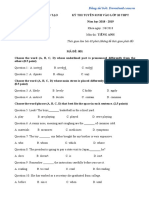

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Figure 1. Rural Sociological Society membership totals, 1997-2007

decline (Figure 1). Membership numbers dipped and remained below

the 1,000 level beginning in 2001, and total membership has declined

in four of the past six years. As of October, 2007 the RSS btisiness office

reported a total of just 782 membersa 29 percent decline from the

1997 high pointand a one-year drop of 6 percent from the nutnber

reported for 2006. At the time of the membership high point in 1997,

RSS counted a combined total of 651 members in the various

"professional" categories (e.g., professional, professional without

jotirnal, and emeritus), and 237 student members. The numbers from

2007 itidicate a combined total of 516 members in the "professional"

categories (professional, professional without journal, new professional,

emerittts, and lifetime), and 184 student membersa 21 percent drop

from 1997 in professional members, and a 22 percent decline in

student members.

A second relevant indicator of otir sittiation involves instittitional

subscriptions to the Society's fiagship journal. Rural Sociology. Institutional subscriptions for many academic journals have exhibited sharp

declines in recent years as libraries responded to budget shortfalls and

rising stibscription costs. However, even though subscription costs for

Rural Sociology have remained comparatively low, tbe decline in

institutional subscriptions over the past two decades has been stistained

and precipitous. As indicated in Figttre 2, the total number of

institutional subscriptions to Rural Sociology dropped from 1,579 in

1986 to just 782 in October, 2007-a decline of over 50 percent. During

Rural Sociology, Vol. 73, No. 1, March 2008

Figure 2.

Institutional subscriptions to Rural Sociology, 1986 to 2007 (selected years)

that same period U.S. institutional subscriptions dropped from 874 to

569 (a 35% decrease), while international subscriptions plummeted

from 705 to just 213 (a 70% decrease). This trend signals a disturbing

reduction in the visibility of and accessibility to reseat ch reported in the

journal. It also represents a major contributor to recent RSS budget

shortfalls, since institutional subscriptions to Rural Sociology comprise

the single largest source of income to the organization.

A third, more qualitative set of indicators involves various expressions

of discontent, uncertainty, and what Mike Bell (2007) recently referred

to as "academic rural doubt" among the RSS membership. This is

evidenced in various waysincluding the commentaiy presented in

several previous RSS Presidential addresses (see Beaulieu 2005; Flinn

1982; Klonglan 1987), articles published over the years in Rural Sociology

and other journals questioning the status and future of both rural

society and rural sociology (Bealer 1969; Bell 2007; Falk and Pinhey

1978; Friedland 1982), discussions and comments presented in

organized sessions at the 2006 RSS meeting focusing on the so-called

"deat!i" of rural sociology, feedback provided to RSS leadership

through organized listening .sessions (Beaulieu 2004), and informal

input that I and others have received through many conversations with

past and present RSS members over the past several years. It is also

evidenced by the disappearance from the annual RSS meetings and

from our membership roster of a considerable number of former

Rural Sociology at the Crossroads Krannich

members whose training, research interests, and positions would

suggest that rural sociology should still be at the core of their

professional identities. To paraphrase a statement from the work of

economist Robert Heilbrontier (1991:11), "there is a qtiestion iti the

air, more sensed than seen, like the invisible approach of a distant

storm.... is there hope" for rtiral sociology?

What factors can we point to in attempting to account for these

trends and this state of unrest? Not surprisingly there are multiple

possible explanations. Some involve forces that are external to RSS,

and, to a considerable extent, beyond our immediate control. At the

same time, some of the contributing factors are internal to our

discipline and our organization, and perhaps more amenable to

collective efforts to implement change.

External Forces

The list of external forces operating largely outside of the organizational reach of RSS that have contribtited to the challenges confronting

r\nal sociology incltides at least the following:

(1) Substantial attrition among an aging cohort of rural sodology

faculty members at U.S. universities, who during the past decade in

particular have moved in growing numbers toward and into retirement.

This reflects a largely "external" process, because it can be traced not

to action (or inaction) on the part of RSS, but instead to the legacy of

earlier faculty expansions that occurred in large part as a response to

movement of the baby-boom generation into and through the

American educational system. The timing of this demographic

transition among the faculties of rural sociology departments and

programs could not have been worse, because it has coincided with an

inability on the part of many academic departments to fill vacant

positions due to budget shortfalls that affected large numbers of public

and private institutions during the same time period. The end results

h'ave inclttded a loss of critical mass in many programs where rural

sociology was once firmly estabUshed, reduced ability of affected

programs to compete at the institutional level for resources and

students, and more generally a shrinking pool of academic professionals whose appointments and research interests make them hkely

candidates for RSS membership.

(2) Topical constraints and stagnant or declining funding opportunities for rural soeiological research. In particttlar, there has been an

erosion of traditional sources of research sttpport such as the formula

funds allocated by the United States Department of Agriculture

Rural Sodology, Vol. 73, No. 2, March 2008

(USDA) through Agricultural Experiment Stations at U.S. Land Grant

universities, and stagnation in the amount of competitive grant funding

available for rural sociological research through key programs such as

the USDA National Research Initiative (NRI).

Rural sociology's reliance on USDA funding has always been a

double-edged sword. Formula funds allocated to support research at

U.S. Land Grant universities have provided a readily accessible and in

many cases essentially guaranteed source of research funding not

enjoyed by social scientists in other disciplines or those otitside of the

land grant system. At the same time, reliance on such funding has

constrained the focus and scope of much rural sociological research to

topics that fit within whatever may be included in the then-current

USDA agenda of priorities and to issues and locations deemed relevant

by Experiment Station administrators whose interests most often are

cente] ed within their own state rather than on topics characterized by a

regional, national, or global focus (see Falk 1996; Flinn 1982; Friedland

1982). In recent years this funding tradition has produced increased

vulneiability for many rural sociology programs and faculty, due to

reduced levels of USDA-administered formula funds allocated to Land

Grant universities and ongoing uncertainty about the future of such

ftmding within the federal budget (see Huffman et al., 2006).

The emergence in 1990 of the NRI competitive grants program,

including in particular the program area focused oti rural development, added another important source of research funding for rural

sociologists, and one that has been more broadly available to

researchers both within and outside of the land grant system. However,

here as well, USDA funding priorities have focused attention on a

relatively limited range of topics, and funding levels for the rural

development program area have lagged substantially behind those in

other NRI programs. The move several years ago to an every-secondyear proposal submission schedule for the NRI rtiral development

program, along with shifts in program priorities from one funding

period to the next, have further constrained the availability of this

source of funding for rural sociological research. To a large extent

these trends reflect the operation of broad-based social and political

forces that have contribtited to a shift in national research ftmding

priorities towatd areas other than the social sciences. At the same time,

the absence of political infiuence on the part of social science in

general and RSS specifically has contributed to a failure to organize and

fight effectively to retain or enhance such resources.

The deterioration and future uncertainty of these traditional funding

sources place rural sociology programs and faculty members at

Rural Sociology at the Crossroads Krannich

increased risk, especially in the context of research-oriented universities

where grantsmanship is increasingly a criterion for resource allocation,

faculty tenure, and program continuance. These circumstances have

contributed both to the loss of faculty positions noted above and to

reduced levels of graduate assistant funding needed to stipport and

train the next generation of rural sociologists, and ultimately to the

pattern of membership decline experienced within the Rural Sociological Society over the past decade.

(3) A gradual disappearance of academic departments that are clearly

defined by name and mission as "rural sociology" programs. Whether

abandoned entirely, absorbed into other types of disciplinary or multidisciplinary departments or given a new label, the result of program

discontinuance, restructuring, and redefinition has been an erosion of

the "rural sociology" label on most university campuses across the

United States. At present, only two explicitly "Rural Sociology"

departments remainat the University of Missouri and the University

of Wisconsin. A handful of other departments retain "rural sociology"

in their names, either listed second after more prominent (and

institutionally dominant) disciplines like "agricultural economics" or

"sociology" or combined with other thematic emphases (e.g.,

Washington State University's department of "Community and Rttral

Sociology"). Elsewhere, the phrase "rural sociology" has essentially

disappeared from the roster of campus department names and

program lahels. Althottgh a considerable amount of rural sociological

education and research remains in evidence within departments of

differetit names, the disciplinary identity and heritage of "rural

sociology" are nevertheless blurred. With this comes a redticed

likelihood that either factilty or studentsparticularly those who arrive

after a department's label has changedwill develop or sustain

personal and professional identities as rttral sociologists, or feel

compelled to establish or maintain membership in something called

the Rural Sociological Society.

(4) Increased competition for memberships, membership dollars,

and professional identity from a large and expanding array of social

science professional organizations. These include long-standing national as well as regiotial disciplinary organizations such as the American

Sociological Association and the Pacific Sociological Association, along

with an ever-growing number of more recently-created interdisciplinary

organizations such as the Agriculttire, Food and Human Values Society,

the Association for the Study of Food and Society, the National Rural

Health Association, the International Association for Society and

Natural Resources, and the Society for Human Ecology.

Rural Sodology, Vol. 73, No. 1, March 2008

Faced with a proliferation of professional associations as well as

constraints on their time, energy, and finances, it was perhaps

inevitable that a number of past as well as potential RSS members

would shift the focus of their organizational involvement and

allegiance, especially as the "rural sociology' identity" has waned across

U.S. university campuses. Nearly 40 years ago Robert Bealer (1969:231)

observed that the "continuing problem of identification...is an issue of

critical importance" for the future of rural sociology. More recently,

Falk (1996) argued that a rural sociological identity was promoted by

common experience within the land grant university context and

shared participation in RSS. Research on social network ties,

comnnmit\' interaction, and collective organization has repeatedly

demonstrated that a shared, overarching identity is key to both

interaction and engagement (see Putnam 2007; Wilkinson 1991).

Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons the RSS has in recent decades

lost ground to other professional organizations that have built their

focus around themes that once were well-established within the rural

sociological enterprise. As a consequence, it seems that in recent years

the "identity" of being a "rural sociologist" has become less and less

compelling for many rural-oriented scholars and practitioners.

(5) A fundamental transformation of "rural society" in the U.S. and

other advanced industrial societies, resulting in an erosion of many of

the content domains that were traditionally at the core of rural

sociology. Twenty-five years ago Friedland wrote of the "death of rural

society," asserting that demographic shifts along with ctilttiral and

economic homogenization had by then reached a point such that there

was "little 'rural' society left in the United States" (1982:590). This is

without doubt even more true in 2007 than it was in 1982.

By 2000, over 80 percent of U.S. citizens lived either in central cities

or in suburban areas of metropolitan areas (Hobbs and Stoops 2002),

;md many of those living in non metropolitan areas were urban-origin

in-migrants attracted by small-town lifestyle opportunities, rural

retirement destinations, and natural amenities (see McGranahan

1999; Winkler et al. 2007). Meanwhile, by 2000 the percentage of the

U.S. workforce employed in agriculttire had dropped to jtist 1.9

percent, and by 2002 only 0.7 percent of the total U.S. GDP came from

agriculttire (Dimitri, Effiand, and Conklin 2005). Long-term employment declines in other ttaditional niral economic sectors such as

forestiy and mining tell a similar story (see Freudenburg, Wilson, and

O'Leary 1998). These shifts in conjunction with the rapidly expanding

communication and information exchange capacities fostered by

electronic technologies have contributed to a situation in which much

Rural Sodology at the Crossroads Krannich

of what we traditionally studied as "rural" is no longer so clearly

evident, or so clearly distinctive, as was previously the case. In turn,

there is no longer an obviotis "constituency" for rural sociological

research, if there was ever one to start wilh (see Friedland 1982). Under

these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that the traditional focus of

rural sociology on "rural people and places" has become less relevant

and less compelling in the eyes of policy makers, funding agencies,

university administrators, the public at large, and students.

Internal Forces

In addition to external forces that often operate beyond the immediate

reach of the Rviral Sociological Society, there undoubtedly are also

some internal forces involving the organizational structure and

behavior of RSS that have contributed to our current situation. These

incltide at least the following:

(1) A somewhat schizophrenic organizational perspective with

respect to the value of application and outreach. Rural sociology has

long been characterized by a more "applied" orientation than is

generally true of most other sociological fields (see Falk 1996; Lobao

2007). Application, public outreach, and policy application have been

self-proclaimed strengths of rural sociology from oiu- earliest days,

placing the field far out in front of more recent calls within the broader

sociological enterprise for development of a "public sociology"

(Burawoy 2005; Sachs 2007). The continued centrality of such an

orientation as a part of both our legacy and our contemporary identity

is evidenced by the recendy-announced theme for the 2008 RSS Annual

Meeting: "Rtiral Sociology as Public Sociology: Past, Present, Future."

At the same time, this more applied orientation has been identified

by some observers as contributing to a tendency for rtiral sociology to

be less highly-regarded than other sociological fields (Bealer 1969;

Friedland 1982). This may help to account for a reluctance on the part

of RSS to wander very far from the path of traditional academic

scholarship. Our organization has for the most part failed to engage

with or effectively recruit participation and membership among those

whose professional roles have more to do with practice and application

than with traditional academic research and scholarship. Despite some

recent efforts to diversify the content of annual meeting programs,

meeting sessions and presentations pertaining explicitly to application

and practice are scarce at best. Meanwhile, the content oi Rural Sodology

remains entirely within the domain of scholarly research, providing no

real opportunity for publication of primarily applied or policy-oriented

10

Rural Sodology, Vol. 73, No. 1, March 2008

work. Our newly-minted applied policy series. Rural Realities, is intended

to provide an outlet for more accessible policy-oriented analyses, but to

date at least those contributing its content have been individ\ials in

traditional academic positions rather than those engaged directly in the

policy arena or in applied professions. Unlike some other professional

organizations (for example, the Nationai Rural Health Association)

that have ptirposeftilly btiilt a membership comprised of both scholars

and practitioners, RSS remains focused on an academic, researchoriented membership base. Stich an approach leads inevitably to a

somewhat limited and shrinking member recruitment potential.

(2) A degree of "boiuidary maintenance" behavior, which has

diverted the interest and participation of some social scientists away

from RSS. This is perhaps best illustrated by the virtual disappearance

over the past 20 years of non-academic natural resource social scientists

from the RSS meetings and from the organization's membership roster.

As Field and Burch (1988) have documented, rural sociology is in many

ways the disciplinary hirthplace of natural resource and environmental

sociology. In 1964, the Rural Sociological Society became the first

professional social science association to formally embrace this

emerging field, when a group that soon became the Natural Resources

Research Grotip (NRRG) was established within RSS. In subsequent

years the NRRG grew to become the largest and perhaps the most

influential of the research and interest groups formed within RSS, with

substantial involvement and group leadeiship occurring among social

scientists working outside of the academic sphere in natural resource

management agencies such as the U.S. Forest Service, the Bureau of

Land Management, and the National Park Service.

By the late 1970s and well into tlie 1980s, this grotip was louunely

organizing a well-attended full-day "mini-conference" in conjunction with

the annual RSS meeting, usually schedtiled for the day immediately

preceding tlie start of the regulai' RSS meeting program. Concerns

eventually emerged within RSS about the possibility that NRRCi (and other

interest groups) might exert undue infltience on the structure of the

annual meeting tlirough these pre-conference activities. This led to a

decision requiring tliat interest group activities and sessions be interspersed throtighout the meeting program, rather than being concentrated

in a full-day pre-conference forum. While there undoubtedly were some

well-reasoned organizational concerns behind this action, an unintended

conseqtietice has been the virttial disappearance of natural resource

agency social scientists from the ranks of RSS membership and meeting

attendees. With very few exceptions these former RSS members have

shifted their attention to other professional associations and other

Rural Sodology at the Crossroads Krannich

11

meeting venues where their identities are more clearly reinforced and

have fueled the emergence of new organizations and new journals that

compete with RSS for visibility, impact, and the allegiance of members.

(3) A largely failed attempt to build stronger bridges between RSS

and the American Sociological Association, and between rural sociology

and the broader sociological discipline. Over the past 10 to 15 years, few

debates within RSS have been as heated or as extended as that involving

the decision in the mid-1990s to hold future RSS meetings during

overlapping time periods and in the same or proximate locations as the

annual meeting of the American Sociological Association on an

alternate-year schedule. Some RSS members welcomed the opportunity

to more easily attend the meetings of both organizations, and

promoted the potential for rural sociology to btiild a closer affiliation

to the broader discipline. Some members opposing the policy decried

both the costs of meeting attendance in large-city convention venues

and the symbolic implications of holding "loiral" sociology meetings in

stich settings. Others expressed concerns about a potential blurring of

the distinct rural sociological identity if RSS and its members were to

become more closely connected lo atid influenced by ASA.

For the most part, neither the anticipated positive consequences or

the anticipated negative consequences of meeting coordination with

ASA have occurred, simply because efforts to schedtile coincident

meeting times and venues have been generally unsuccessful. Several

times during the past decade ASA has shifted its annual meeting to an

entirely different city and region in response to unresolved contractual

issties between hotel worker labor unions and convention hotels.

Unfortunately, those decisions occurred after RSS had established

contractual obligations for a meeting ventte that could not be

abandoned without incurring substantial financial penalties. As a

result, an tinintended consequence of this policy has been the location

of several recent RSS meetings in less-than-ideal locationssites that

undoubtedly would not have been selected in the absence of efforts to

coordinate with ASA meeting plans.

These circumstances have without question contributed to reduced

attendance at RSS meetings over the past decade. Some members,

confronted with an inability to participate in two temporally proximate

btit geographically distant conferences, have chosen instead to attend

ASA meetings. Others have bypassed RSS meetings held in what they

considered to be inconvenient, unattractive, or overly expensive

locatiotis. Reduced meeting attendatice contributes in ttxrn to reduced

effectiveness at both new member recruitment and member retention,

and to further erosion of the "rural sociology" identity.

12

Rural Sociology, Vol. 73, No. 1, March 2008

(4) Organizational inertia. The Rural Sociological Society has been

slow to respond to changing circumstances, due at least in part to an

unwieldy and cumbersome organizational .structure. Along with six

officers and seven elected council members, RSS has eleven standing

committees and at present four ad hoc committees, each with a chair

and multiple (in some cases 10 or more) committee members. In

addition, each ofthe fourteen Research and Interest Groups has its own

chair or co-chairs, and in some cases other officers. At any given time

there are 100 or more individuals listed on the rosters of the various

committees that comprise the organization chart for RSS. For a

professional association that now has fewer than 800 members, we are a

very complex organization!

On the plus side, this structure provides considerable opportunity for

a substantial proportion ofthe RSS membership to become involved in

various facets of organizational decision-making and leadership. In

addition, the broad-based representation of our membership in

committee assignments and council positions insures that virtually all

organizational affairs and proposals for action will be fully vetted from

multiple perspectives. At the same time, there are important liabilities

associated with such a complex leadership and committee structure.

Even though some elected and appointed positions involve two or

three-year terms, the annual turnover in RSS officers, council members,

committee chairs, and committee membership results inevitably in

organizational inefficiencies that make it difficult for RSS to pursue

sti'ategic planning, to reach major organizational decisions, or to insure

follow-through on decisions previously made. Each year, newlyconfigured committees inherit a range of existing and in-process tasks

not completed during the prior year, most often in conjunction with a

completely new set of charges put forth by an incoming president. The

time required for new chairs and committee members to learn about

their assignments, allocate responsibilities, and tackle their list of tasks

often means that real progress does not begin to occur until at least

several months after committee terms begin. At that point, only a few

months remain before terms end, committees are reconfigured, and

the process starts all over again. Institutional memory and followthrough suffer in this context of repeated starts, stops, and re-starts,

making real action difficult to accomplish.

Added to this is a hesitancy on the part of many, if not most, RSS

committee chairs and elected officers to effect major changes to the

organization and its activities when there is a diversity of opinion

among members about alternative paths and future options. As an

organization and as individuals, we tend to promote and value broad-

Rural Sociology at the Crossroads Krannich

13

based input and open dialogue about the issues and choices that

confront RSS. This is one of the strengths of our organization, and

certainly one that merits protection. At the same time, it is important to

recognize that the choices before us are difficult, and that consensus is

not likely to emerge. At some point it is necessary to move beyond

introspection and dialogue into actionand that has proven to be a

difficult step for RSS to take.

So Where Do We Go From Here?

Although "rural society" is less extensive and certainly very different

than has been the case historically, it is important to keep in mind that

one in five U.S. residents still lives in a nonmetropolitan setting, and

that in 2007 just slightly imder one-half of the world's population is

rural (see Wimberly, Morris, and Fulkerson 2007). Rural places and

populations remain at the center of an international agricultural

industry that has evolved into a complex, hierarchical world food

system that has important implications for the health and security of

rural and urban people across the globe (see Buttel, Larson, and

Gillespie 1990; Friedland 1982). Community-based natural resource

management provides a context within which the pursuit of ecological

as well as social well-being are intricately intertwined in rural

communities across both developed and developing societies (see

Baker and Kusel 2003; Wilkinson 1991). Spatially differentiated and

persistent patterns of poverty, inequality, and injustice continue to

plague rural people throughout the world and continue to call for

resolution (Lobao 2004). At the same time, deeply rooted societal

ideals about "rurality" and the attractions associated with rural

landscapes continue to influence public opinion, recreation and

tourism patterns, migration behaviors, and political decisions in the

United States and other advanced industrial societies. Even where

"rural society" has waned, rural remains an important "category of

thought" (Mormont 1990:41, as cited in Bell 2007)a social

construction that is deeply embedded in cultural and political discourse

(see Bell 2007).

While many additional topics and themes could be listed, it seems

obvious that the work of rural sociologists remains relevant and

important even though "rural society" has morphed into something

decidedly different in the 21" century. Indeed, as Don Dillman (2007)

has recently observed, rural social science may now be more important

than ever, largely because of major shifts that continue to alter the

social, economic, and biophysical landscapes of the rural countryside.

Rural Sociology, Vol. 73, No. 1, March 2008

Old assumptions about rural community decline and the growing

irrelevance of locality as a foimdation for social organization are

repeatedly contradicted by evidence that reveals a persistence and even

a resurgence of locality-based activity and action across much of rural

America (see Luloff and Krannich 2002). Continued transformations in

communication technologies have dramatically altered tlie spatial

constraints on interaction long connected with rurality, with consequences for personal and collective well-being that are still only partially

understood. Global climate change has the potential to create dramatic

ecological upheavals that could significantly alter agricultural production pattems, the availability and allocation of water resources, and

future migration patterns. Declining petroleum resources and global

political tensions are stimulating a rapid shift toward bio-fuel

production that has the potential to alter economic, demographic,

and ecological conditions throughout much of rural America. At the

same lime, the potential for a future shift entirely away from economies

built around carbon fuels portends even more dramatic transformations. On balance, there can be little doubt that many important

questions remain to be addressed by rural social scientists.

The legacy and continued strengths of the Rural Sociological Society

also seem still to matter, in spite of our recent downward trend. RSS

members care about, contribute lo, and value both research and

application. As a group, we are committed to social change that will

promote the well-being of rural people and communities. That

commitment is reflected in a strong focus on addressing real-world

problems through original research, infonnation dissemination, policy

assessment, and action. We are highly inclusive and value the ways in

which a variety of disciplinary perspectives, theoretical orientations, and

methodological approaches can illuminate the conditions and changes

confronting rural societies around the globe. We also value and nurture

a tradition of informality, collegiality, fellowship, and networking that

has made RSS truly special, both in terms ofthe strong professional ties

that link us as colleagues and collaborators and the enduring

friendships and socializing that make attendance of our annual

meeting so enjoyable.

In short, there is much about tbe field of rural sociology, and about

the Riual Sociological Society, that is worth saving. We need to preserve

and build upon our legacy and our strengths, but we also need to think

strategically about new directions. We can undoubtedly "fine tune" our

existing course in a variety of waysperhaps by reconsidering the

locations and even the timing of annual meetings; by "spicing up" the

content and structure of the annual meeting program; by selectively

Rural Sociology at the Crossroads Krannich

15

adjusting the length of terms for certain leadership and committee

chair positions; or by reconsidering the number, size, and even the

need for some of the organization's committees. Even such relatively

mild redirections will undoubtedly generate some controversy among

members with diverse perspectives and preferences. However, these

types of small, incremental change will by themselves not suffice in

responding to the challenges before us^we will also need to pursue

more fundamental changes to the structure and activities of RSS. To

accomplish this, we can take guidance from the work of market strategy

specialists Kim and Mauborgne (2005), who distinguished between

"red ocean" situations in wbich multiple competitors vie for customers

and constituents in a crowded market space, and "blue ocean"

situations characterized by essentially open and untapped markets, the

chance to create new demand, and substantial growth opportunity.

The "Red Ocean" Context

At present, RSS operates almost entirely within a "red ocean" context,

where we compete head-to-head with multiple other professional

organizations for membership, meeting attendance, visibility, and

impact. In a variety of ways our competitive situation in the several

arenas that comprise this "red ocean" is not particularly advantageous.

For example, within the realm of disciplinary sociology we are

confronted by the American Sociological Association, the discipline's

"800 pound organizational gorilla." By virtue of membership size, fiscal

resources, staffing levels, organizational visibility, and disciplinary

prestige, ASA is clearly dominant in competing for the attention and

allegiance of U.S. sociologists. Meanwhile, multiple smaller regional

sociological associations compete for membership among those whose

professional identities are firmly situated in the realm of disciplinary

sociology but who prefer affiliation with smaller and perhaps more

accessible professional organizations. With reference to the broader

discipline of sociology at least, RSS has been and undoubtedly will

remain a marginal competitor among multiple professional associations and societies.

We also confront a red ocean with respect to several specialized

content areas where rural sociology has traditionally been strong, and

where we continue to compete. For example, while population studies

represent a well-established field of interest among rural sociologists,

the Population Association of America has 3,000 members and a much

stronger presence among U.S. scholars whose core identities are

focused around demography. Although a number of rural sociologists

16

Rural Sociology, VoL 73, No. I, March 2008

maintain a strong interest in health-related topics, the National Rural

Health Association has in just 20 years grown to become a very large

(over 15,000 members) organization with a dominant position in that

specific domain. Multiple organizations, including the International

Association for Society and Natural Resources, the Society for Human

Ecology, and the Social Science Working Group in the Society for

Conservation Biology, have emerged as alternative and perhaps more

central professional homes for those whose identities focus more on

environmental/natural resource social science than on rural studies.

The fact that there are multiple and, in many cases, stronger

organizational competitors in disciplinary sociology and in several

specific content areas where rural sociologists are engaged does not

mean that either our discipline or RSS should divert attention away

from those domains. As Kim and Mauborgne (2005: 5) suggest, "it will

always be important to swim successfully in the red ocean... red oceans

will always matter, and will always be a fact of... life." RSS should

certainly continue to embrace its disciplinary foundations in sociology.

We sbould also continue to provide an organizational home for those

whose interests in population dynamics, environment and natural

resources, agriculture and food systems, land use and tenure, labor

force issues, community, health, social inequality, race and ethnicity,

aging, gender, family, and a myriad of other topics converge around a

common interest in rural contexts. In short, RSS needs to remain

broadly inclusive and eclectic in order to maintain position in the

competitive arenas where it is already established, even where other

organizations have captured stronger positions.

The Blue Ocean Option

At the same time, RSS also needs to move beyond these existing

competitive arenas, and chart new courses in a less-contested "blue

ocean" environment. To accomplish this, several areas of opportunity

should be considered.

First, RSS should focus attention more explicitly on the shared

interests and identities that can be forged by capitalizing on interest

across multiple disciplines and .subdisciplines in "things niral."

Increased emphasis on interdisciplinary and even transdisciplinary

learning and research, both within higher education and in the

funding priorities of major research foundations and agencies,

reinforces the need to extend the RSS identity and "brand" beyond

its disciplinary roots in sociology. In short, RSS needs to pursue a much

more explicitly interdisciplinary courseone that would move our

Rural Sociology at the Crossroads Krannich

17

collective identity beyond "rural sociology" to a more broadly-defined

domain of "rural social sciences." In many ways rural sociologists have

at least as much in common with geographers, anthropologists, political

scientists, and others from allied social science fields whose interests

converge around "rural" themes as they do with sociologists working in

the broad array of specializations that characterize what has become a

highly-fragmented discipline.

Amove toward this more interdisciplinary/transdisciplinary position

is hindered by the image or "brand" that characterizes the Rural

Sociological Society. For that reason, it is time to change the n;une of

our organization and of our journals and other products, and to create

a new organizational identity that refiects a more inclusive and more

interdisciplinary orientation. Although several suggestions come to

mind regarding new labels for the organization (e.g., the "International Association for Rural Studies") and the journal (e.g.. Rural

Dmjelofrmimt and Social Change: An IntetdLsciplinary /mirnati,

this will

admittedly be a difficult transition, one that will undoubtedly generate

extended dialogue and debate among members. Yet it will also be

important to move beyond that admittedly difficult, symbolic first step

of renaming the organization by also changing our organizational

behaviorsRSS needs to become more proactive in attracting niral

scholars in allied social science fields to participate in our annual

conference, to publish in our journals, and to engage as members of a

reconfigured professional organization.

Second, tbere are opportunities to pursue an expanded research

agenda and membership base that would extend the reach of RSS (or

whatever it becomes) more effectively beyond the boundaries of the

United States. Although tliere is already an "international" umbrella

organization for rural sociology (the International Rural Sociological

A.ssociation, of which RSS is a member organization) and several rural

sociology associations focused on particular world regions (e.g., the

European Rural Sociological Association and the Latin American Rural

Sociological Association), that should not preclude RSS from pursuing

a stronger international position and reputation. An expanded,

interdisciplinary focus on rural social sciences that encompasses

research and application across international contexts, particularly

one that promotes cross-national comparative studies and analyses of

global systems, could substantially extend the scope and visibility of our

organization and the rural social science disciplines that it might

encompass. A move in this direction could be pursued in multiple

waysperhaps in part through changes to the names of the

organization and its products, through targeted solicitation of

18

Rural Sociology, Vol. 73, No. 1, March 2008

manuscripts for submission to the organization's journals, through

strategic recruitment and publication of manuscripts published in the

Rural Studies Series, through thematic sessions in annual meeting

programs and proactive recruitment of a new cadre of participants, and

through collaborative organization of future meetings with other

organizations that are already more engaged in international research

and application, including some .situated outside of the United States.

Third, it should be possible for us to become more inclusive and

more relevant with respect to policy-oriented and application-based

work, to build a stronger connection with professionals engaged in

activities outside of the academy, and to recruit a larger and more

diverse group of practice-oriented members. This could be accomplished in part through strategic partnerships wilh olher professional

associations where practitioners focus on rural development and the

welfare of niral people. Such partnerships could including the

occasional scheduling of joint meetings to encourage cross-fertilization,

as well as collaborative pursuit of projects or development of products

focusing on key issues where rural social science and practical

application converge. The RSS annual meeting could be resuuctured

to include an expanded array of sessions and participants focusing

explicitly on practice and application. Similarly, our journal could

follow the lead of some other peer-re\iewed social science journals by

making room for high-quality "application" pieces aiong with more

traditional research arlicles. If our legacy and our identity are defined

in part by a commitment to application and to engagement on behalf of

rural people, communities, and organizations, it would seem entirely

reasonable to have that refiected more explicitly in the activities and

products of the organization. Doing so could help rural sociology to

more effectively identify and nurture an external constituency that

could help to reinforce and defend the relevance and the importance

of our educational programs, our research, and our contributions to

policy discourse.

Fourth, we need to identify and pursue a series of high-visibility, highimpact initiatives and products that can highlight how in specific,

thematically focused ways our organization and its members can

contribute to understanding and helping lo resolve key challenges

confronting rural communities and people across both domestic and

international contexts. RSS bas accomplished this kind of outcome

previously, most notably through the work of the Task Force on

Persistent Rural Poverty assembled in 1990 by past-Presidenl Gene

Summers (see Rural Sociological Society Task Force on Persistent Rural

Poverty 1993). This represents an important example of how RSS has in

Rural Sociology at the Crossroads Krannich

19

the past seized a "blue ocean" opportunity by pursuing an important

issue and having major impact within and beyond the academic arena.

Such activities should be structured in a manner that would

simultaneously build on our current strengths and forge new

Interdisciplinary and international bridges and visibility. With lhe

Rural Sociological Society's 75^^ Anniversary occurring in just four

years, tlie time is ripe to move forward on this front.

Conclusion

The theme of the 2007 RSS annual meeting, "Social Change and

Restructuring in Rural Societies: Opportunities and Vulnerabilities,"

was designed to focus attention on both the vulnerabilities and the

opportunities that accompany social change and restructuring in rural

societies. Similarly, the forces of change confronting the discipline of

rural .sociology and the Rural Sociological Society present us with bolh

vulnerabilities and opportunities. We undoubtedly have the capacity to

adapt to changing circumstances, to chart a different course, and to

reconfigure RSS into an organization that will remain strong and vital

into the distant future. The question is, do we have the will to do so?

Are we prepared to take action?

In his seminal work on community, Kenneth Wilkinson (1991) wrote

about five key elements of well-being that should be kept in mind as we

venture forward. Central to Wilkinson's discussion of well-being is

collectiveflc/io^"peopleworking together in pursuit of their common

interests" (1991:74). Clearly, members ofthe Rural Sociological Society

need to engage in collective action to address the challenges confronting

our professional field and our association. In doing so we will "promote

and enrich the collective life" (p. 74) experienced through social

interactions that comprise the foundation of this organization.

However, our attempts at action will undoubtedly fall short if we fail

to recognize and nurture the other four elements of well-being that

Wilkinson identified. We must endorse the importance of distrilmtive

justicemeaning equit)' and justice as principles of interaction as we

engage in frank conversation and difficult decision-making about the

future of RSS. We musl foster open communicationboth through

creation of efficient channels for dialogue among members and

through adherence to the principles of "honesty, completeness, and

authenticity" (p. 73) in the communication process. As, was noted

earlier, we cannot allow differing perspectives to block decision making

and action, yet at the same time we must expect and promote tolerance

of differing viewpoints, and respect the right of others to disagree.

20

Rural Sodology, Vol. 73, No. 1, March 2008

Finally, we need to use this historic moment in the trajectory of RSS

to experience communion. By taking the opportunity to celebrate our

collective heritage, recognize the personal and professional relationships that bind us into an organization, and promote the shared values

and purposes that can guide our actions, we will enhance our capacity

to work together on behalf of the rural sociological enterprise and

move RSS forward.

References

Baker. M. and J. Kusel. 2003. Communily Forestry in the United Slates: learning from the Past

Washington, DC: Island Press.

Bealer, R.C. 1969. Ideniity and ihe Future of Rural Sociology."fiura/.Sftriw/wgy34:229-33.

Beaulieu, L.J. 2005. "Breaking WalLs, Building Bridges: Expanding the Presence and

Relevance of Rural Sodology." Rural Sociology 70:1-27.

. 2004. "Building a Foundation for the Future: Perspectives from the 2004 RSS

Business Meeting." Thu Rural Sociologist 24:20-21.

Bell, M.M. 2007. "The Tivo-ness of Riual Life and the Ends of Rural Scholarship." youma/

af Rural Studies 23:402-415.

Burawoy, M. 2005. "For Public Sociology." American Sociological Review 70:4-28.

Buttel. F.H., O.F. Larson, and G.W. Gillespie. Jr. 1990. The Sociology of Agriculture. New

York: Greenwood.

Dillman, D.A. 2007. "Rural Social Science; Now More Important than Ever." Department

of Sociology Lecture presented as part of the Iowa Stale University, College of

Agriculture and Life Sciences 150"' Anniversary Celebration Lectures. Ames, Iowa.

October 15.

Dimitri, C . A. EfEland, and N. Conklin. 2005. The 2tf* Centuiy Tramformation of U..S.

Agriculture and Farm Polity. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Etonomic Research Service.

Falk, W.W. 1996. "The Assertion of Identity in Rural Sociology." Rural Sodologf 61.159-14.

Falk. W.W. and T.K. Pinhey. 1978. "Making Sense of ihe Concept Rural and doing Rural

Sociology: An Interpretive Perspective." Rural Sodolngf 4^:547-5S.

Field, D.R. and W.R. Burch, Jr. 1988. Rural Sodology and the Environment. Westport, CT:

Greenwood.

Flinn. W.L. 1982. "Rural Sociology: Prospects and Dilemmas in the 1980s." Rural Sociology

47:1-16.

Freudenburg, W.R., L.J. Wilson, and D.j. O'lxar>. 1998. "Forty Years of Spotted Owls? A

Longitudinal Analysis of Logging Industry Joh Losses." Sociological Perspectives 41:12fi.

Friedland, W. 1982. "The End of Rural Society and the Future of Rural Sociology." Rural

Sochli>gy 47:589-608.

Heilbronner, R. 1991. An Inquiry into the Human Prospect New York: W.W. Norton and Co.

Hobbs, F. and N. Stoops. 2002. Demographic Trends in the 2(/'' Century. Washington, DC:

U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau.

Hulfman, W.E.. G. Norton, G. Traxler, G. Frisvold, and J. Foltz. 2006. "Winners and

Losers: Formula versus (Competitive Fimding of Agricultural Research." Choices

21:269-74.

Kim, W.C. and R. Mauborgne. 2005. Blue Ocean Strategy. Boston, MA: Harvard Business

School Press.

Klonglan, G.E. 1987. "The Rural Sociological Enterprise: A Dist:iptine in Transition."

Rural Sodohgf 52:1-'12.

Lobao, L. 2007. "Rural Sociology." Pp. 465-476 in The Hamibook of 21" Century Sociology,

edited by C D . Bryant and D.L. Peck. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Rural Sodology at the Crossroads Krannich

21

. 2004. "Continuity and Change in Place Stratification: Spatial Inequality and

Middle-range Territorial Units." Rural Sodology 61:77-102.

Luloff, A.E., and R.S. Krannich, eds. 2002. Persistence and Change in Rural Communities.

Wallingfbrd. UK: (^kBI.

McGranahan, D. 1999. Natural ATOenities Drive Rural Population Change. ERS-781, U.S.

Deparuiient of Agriculture. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Mormont, M. 1990. "Who is Rural? Or, How to be Rural : Towards a Sociology of the

Rural." Pp. 21-44 in Rural Restmrluring: Clobdl Processes and Their Responses, edited by

T. Marsdcn. P. Lowe, and S. Whatmore. London: Da\Td Fulton Publishers.

Putnam. R.D. 2007. "K. Plvribus Unum: Diversity and Community in ihe Twenty-first

Century." .Scandinavian Political .Studies 30:137-74.

Rural Sociological Society Task Force on Persistent Rural Poverty. 199S. Persistent Potterty in

Rural America. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Sachs, C. 2007. "C^jing Public: Networking Globally and Locally." Rural Sodobgy 7h2--i4.

Wilkinson, K.P. 1991. The Community in Rural America. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Wimberly, R., L. Morris, and G. Fulkerson. 2007. "Mayday 23: World Population becomes

more Urban ihan Rural." The Rural Sodologist 27:42.

Winkler, R., D.R. Field, .\.K. Luloff, R.S. Krannich, and T. Williams. 2007. "Social

Landscapes of the Inter-Mouniain West: A Comparison of 'Old West' and 'New West"

Communities." Rural Sodology 72:478-501.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Revision FinalDocument6 pagesRevision Finalnermeen mosaNo ratings yet

- Tech Refresh & Recycle Program: 2,100PB+ of Competitive GearDocument1 pageTech Refresh & Recycle Program: 2,100PB+ of Competitive GearRafi AdamNo ratings yet

- Rapport 2019 de La NHRC de Maurice: Découvrez Le Rapport Dans Son IntégralitéDocument145 pagesRapport 2019 de La NHRC de Maurice: Découvrez Le Rapport Dans Son IntégralitéDefimediaNo ratings yet

- Handout On Reed 1 Initium Fidei: An Introduction To Doing Catholic Theology Lesson 4 Naming GraceDocument8 pagesHandout On Reed 1 Initium Fidei: An Introduction To Doing Catholic Theology Lesson 4 Naming GraceLEILA GRACE MALACANo ratings yet

- 25 Useful Brainstorming Techniques Personal Excellence EbookDocument8 pages25 Useful Brainstorming Techniques Personal Excellence EbookFikri HafiyaNo ratings yet

- Indian Accounting StandardsDocument4 pagesIndian Accounting StandardsManjunatha B KumarappaNo ratings yet

- Đề thi tuyển sinh vào lớp 10 năm 2018 - 2019 môn Tiếng Anh - Sở GD&ĐT An GiangDocument5 pagesĐề thi tuyển sinh vào lớp 10 năm 2018 - 2019 môn Tiếng Anh - Sở GD&ĐT An GiangHaiNo ratings yet

- Customer Based Brand EquityDocument13 pagesCustomer Based Brand EquityZeeshan BakshiNo ratings yet

- DEALCO FARMS vs. NLRCDocument14 pagesDEALCO FARMS vs. NLRCGave ArcillaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 - Introduction - A2LDocument40 pagesLecture 1 - Introduction - A2LkhawalmannNo ratings yet

- Dr. Thi Phuoc Lai NguyenDocument3 pagesDr. Thi Phuoc Lai Nguyenphuoc.tranNo ratings yet

- Effecting Organizational Change PresentationDocument23 pagesEffecting Organizational Change PresentationSvitlanaNo ratings yet

- BP - Electrical PermitDocument2 pagesBP - Electrical PermitDwinix John CabañeroNo ratings yet

- ChildBook Mother Is Gold Father Is Glass Gender An - Lorelle D Semley PDFDocument257 pagesChildBook Mother Is Gold Father Is Glass Gender An - Lorelle D Semley PDFTristan Pan100% (1)

- тест юніт 1Document3 pagesтест юніт 1Alina BurdyuhNo ratings yet

- VI Sem. BBA - HRM Specialisation - Human Resource Planning and Development PDFDocument39 pagesVI Sem. BBA - HRM Specialisation - Human Resource Planning and Development PDFlintameyla50% (2)

- A Bibliography of China-Africa RelationsDocument233 pagesA Bibliography of China-Africa RelationsDavid Shinn100% (1)

- Six Sigma and Total Quality Management (TQM) : Similarities, Differences and RelationshipDocument15 pagesSix Sigma and Total Quality Management (TQM) : Similarities, Differences and RelationshipSAKTHIVELNo ratings yet

- 1) Anuj Garg Vs Hotel Association of India: Article 15Document26 pages1) Anuj Garg Vs Hotel Association of India: Article 15UriahNo ratings yet

- BINUS University: Undergraduate / Master / Doctoral ) International/Regular/Smart Program/Global Class )Document6 pagesBINUS University: Undergraduate / Master / Doctoral ) International/Regular/Smart Program/Global Class )Doughty IncNo ratings yet

- 1170.2-2011 (+a5)Document7 pages1170.2-2011 (+a5)Adam0% (1)

- Censorship Is Always Self Defeating and Therefore FutileDocument2 pagesCensorship Is Always Self Defeating and Therefore Futileqwert2526No ratings yet

- Meeting Consumers ' Connectivity Needs: A Report From Frontier EconomicsDocument74 pagesMeeting Consumers ' Connectivity Needs: A Report From Frontier EconomicsjkbuckwalterNo ratings yet

- Perception of People Towards MetroDocument3 pagesPerception of People Towards MetrolakshaymeenaNo ratings yet

- Courts Jamaica Accounting and Financing ResearchDocument11 pagesCourts Jamaica Accounting and Financing ResearchShae Conner100% (1)

- MTWD HistoryDocument8 pagesMTWD HistoryVernie SaluconNo ratings yet

- CHEM205 Review 8Document5 pagesCHEM205 Review 8Starlyn RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Debut Sample Script PDFDocument9 pagesDebut Sample Script PDFmaika cabralNo ratings yet

- Frankfurt Show Daily Day 1: October 16, 2019Document76 pagesFrankfurt Show Daily Day 1: October 16, 2019Publishers WeeklyNo ratings yet

- Place of Provision of Services RulesDocument4 pagesPlace of Provision of Services RulesParth UpadhyayNo ratings yet