Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Trinh, T. T., Chan,, L. A. Peripheral Venous Catheter-Related Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteremia. Infection Contro

Uploaded by

Rosy SanchezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Trinh, T. T., Chan,, L. A. Peripheral Venous Catheter-Related Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteremia. Infection Contro

Uploaded by

Rosy SanchezCopyright:

Available Formats

See

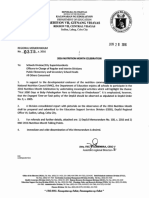

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51113862

Peripheral Venous Catheter-Related

Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia

ARTICLE in INFECTION CONTROL AND HOSPITAL EPIDEMIOLOGY JUNE 2011

Impact Factor: 4.18 DOI: 10.1086/660099 Source: PubMed

CITATIONS

READS

37

233

8 AUTHORS, INCLUDING:

Brian Hollenbeck

Brian L Huang

Lifespan

University of California, Los Angeles

3 PUBLICATIONS 40 CITATIONS

20 PUBLICATIONS 112 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

SEE PROFILE

Julie Jefferson

Rhode Island Hospital

10 PUBLICATIONS 97 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Available from: Brian L Huang

Retrieved on: 04 April 2016

infection control and hospital epidemiology

june 2011, vol. 32, no. 6

original article

Peripheral Venous Catheter-Related

Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia

T. Tony Trinh, MD;1 Philip A. Chan, MD;1,4 Omega Edwards, MD;1,4 Brian Hollenbeck, MD;1 Brian Huang, MD;1

Nancy Burdick, RN;2 Julie A. Jefferson, RN, MPH;3 Leonard A. Mermel, DO, ScM1,3,4

objective. Better understand the incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of peripheral venous catheter (PVC)related Staphylococcus

aureus bacteremia.

design. Retrospective study of PVC-related S. aureus bacteremias in adult patients from July 2005 through March 2008. A pointprevalence survey was performed January 9, 2008, on adult inpatients to determine PVC utilization; patients with a PVC served as a cohort

to assess risk factors for PVC-related S. aureus bacteremia.

setting.

Tertiary care teaching hospital.

results. Twenty-four (18 definite and 6 probable) PVC-related S. aureus bacteremias were identified (estimated incidence density, 0.07

per 1,000 catheter-days), with a median duration of catheterization of 3 days (interquartile range, 26). Patients with PVC-related S. aureus

bacteremia were significantly more likely to have a PVC in the antecubital fossa (odds ratio [OR], 6.5), a PVC placed in the emergency

department (OR, 6.0), or a PVC placed at an outside hospital (P p .005 ), with a longer duration of catheterization (P ! .001 ). These PVCs

were significantly less likely to have been inserted in the hand (OR, 0.23) or placed on an inpatient medical unit (OR, 0.17). Mean duration

of antibiotic treatment was 19 days (95% confidence interval, 1523 days); 42% (10/24) of cases encountered complications. We estimate

that there may be as many as 10,028 PVC-related S. aureus bacteremias yearly in US adult hospitalized inpatients.

conclusion. PVC-related S. aureus bacteremia is an underrecognized complication. PVCs inserted in the emergency department or at

outside institutions, PVCs placed in the antecubital fossa, and those with prolonged dwell times are associated with such infections.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011;32(6):579-583

Central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infections affect an estimated 41,000 patients per year in US hospitals.1

Although the risk of bloodstream infection associated with

peripheral venous catheter (PVC) use is lower than that associated with other intravascular devices,2 there is far greater

use of these catheters than of central venous catheters

(CVCs),3-6 leading to the potential for serious infections in

large numbers of patients.6,7

Staphylococcus aureus is the second most common cause

of hospital-acquired bloodstream infection,8 and it is the

pathogen most often associated with serious and costly catheter-related bloodstream infections,9 such as endovascular

and disseminated infections.10,11 Patients with PVC-related S.

aureus bacteremia have a higher risk of complications compared with such infections due to other pathogens.6 Thus, we

set out to determine the incidence, risk factors, treatment,

and outcome of PVC-related S. aureus bacteremia at our

hospital.

methods

We retrospectively reviewed adult patients admitted to our

tertiary care hospital from July 1, 2005, through March 31,

2008, with S. aureus bacteremia. An episode of definite PVCrelated S. aureus bacteremia was defined as a patient with

blood cultures growing S. aureus, a PVC tip culture or PVC

insertion site culture growing S. aureus, no other source of

S. aureus bacteremia identified, and physician or intravenous

(IV) nursing team documentation noting the PVC as the

source of bacteremia. A case of probable PVC-related S. aureus bacteremia was defined as a patient with physical findings

suggesting a PVC infection (erythema, induration, phlebitis,

drainage, or palpable cord related to the PVC insertion site);

no other source of bacteremia based on medical record review

but in whom there was no culture of the PVC tip or drainage

from the insertion site; and no physician, nursing, or IV

nursing team documentation that the PVC was the source of

S. aureus bacteremia. Phlebitis was assessed using the Visual

Affiliations: 1. Department of Medicine, Rhode Island Hospital, and Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island;

2. Department of Nursing, Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, Rhode Island; 3. Department of Epidemiology and Infection Control, Rhode Island Hospital,

Providence, Rhode Island; 4. Division of Infectious Diseases, Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, Rhode Island.

Received September 28, 2010; accepted December 18, 2010; electronically published April 29, 2011.

2011 by The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. All rights reserved. 0899-823X/2011/3206-0007$15.00. DOI: 10.1086/660099

580

infection control and hospital epidemiology

june 2011, vol. 32, no. 6

Infusion Phlebitis score (1, pain and redness around the insertion site; 2, pain, swelling, erythema, and a palpable venous

cord; 3, pain, swelling, erythema, palpable venous cord beyond 3 cm, and the presence of a purulent exudate; 4, all of

the above and evidence of tissue damage). This study was

approved by the Rhode Island Hospital Institutional Review

Board.

Source Identification

Rhode Island Hospital infection control software (Theradoc)

was searched for all microbiologic cultures growing S. aureus

from adult inpatients during the study period. For each patient with S. aureus bacteremia, we reviewed all other cultures

growing S. aureus for 3 months after the S. aureus bacteremia

was documented. Cases of S. aureus bacteremia with a PVC

tip or insertion site wound culture growing S. aureus within

3 days of S. aureus bacteremia were included as cases. Patients

with S. aureus bacteremia without an identified microbiologic

source were further reviewed using electronic patient data. If

there was no identifiable source of bacteremia, we crossreferenced each such case with the IV nursing team records.

Analysis

To estimate total PVC-days during the study period, we used

hospital administrative data to determine the total number

of adult inpatient-days during the study period, and we multiplied that number by the fraction of adult inpatients with

a PVC during a point-prevalence survey we performed on

January 9, 2008, on all adult inpatient units.

Medical record review was performed on all cases of PVCrelated S. aureus bacteremia. Descriptive statistics were generated for demographic and clinical parameters. The MannWhitney U test was used to determine the differences in

duration of catheterization between the patients with PVCrelated S. aureus bacteremia and patients in the PVC pointprevalence survey; otherwise, the Fischer exact test was used.

results

A total of 544 cases of S. aureus bacteremia were identified

(Table 1). Twenty-four (18 definite and 6 probable) PVCrelated S. aureus bacteremias were identified in 24 patients

with a mean age of 63 years (95% confidence interval [CI],

5571 years; Table 2). There were 451,366 adult patient-days

during the study period. In our point-prevalence survey, 298

of 392 of adult inpatients (76%) had a PVC. Thus, during

the study, there were approximately 343,130 PVC-days, leading to an estimated incidence density of PVC-related S. aureus

bacteremia of 0.07 per 1,000 PVC-days.

For 16 of the PVC-related S. aureus bacteremias (67%),

the PVC was placed in our emergency department, 4 (17%)

were placed in an inpatient unit, 2 (8%) were placed by

emergency medical services prior to admission, and 2 (8%)

were placed at outside hospitals. There was no temporal clustering of PVCs inserted in our emergency department that

table 1. Source of Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia

Source

Soft tissue or bone

CVC or PICCa

Pulmonary

PVC

Endovascular

Urinary tract

Otherb

Unknown

Total

(n p 544)

204

172

88

24

12

12

9

23

(37)

(32)

(16)

(4)

(2)

(2)

(2)

(4)

MSSA

(n p 296)

116

77

43

16

11

8

5

21

(39)

(26)

(15)

(5)

(4)

(3)

(2)

(6)

MRSA

(n p 248)

89

95

45

8

1

4

4

2

(36)

(38)

(18)

(3)

(0.4)

(2)

(2)

(1)

note. Data are no. (%).

a

CVC, central venous catheter; MRSA, methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter;

PVC, peripheral venous catheter.

b

Other includes S. aureus bacteremia associated with injection drug use (6), infected pacemaker (1), traumatic paracentesis (1), or traumatic bladder catheter insertion (1).

led to S. aureus bacteremias. Eleven of the 24 PVCs (46%)

were in the right antecubital fossa, 5 (21%) in the right forearm, 1 (4%) in the right hand, 5 (21%) in the left antecubital

fossa, 1 (4%) in the left forearm, and 1 (4%) in the left hand.

The mean visual phlebitis score was 3 (95% CI, 2.43.4).

Compared with the those in the point-prevalence survey, patients with PVC-related S. aureus bacteremia were more likely

to have the PVC inserted in the emergency department or at

an outside hospital and more likely to have the PVC in the

antecubital fossa (Table 3). The median duration of PVC

dwell time before the blood culture was obtained that grew

S. aureus was 3 days (interquartile range [IQR], 36 days),

compared with a median duration of PVC placement of 1

day (IQR, 12 days) in the point-prevalence survey (P !

.001).

The mean hospital duration for patients with PVC-related

S. aureus bacteremia was 15 days (95% CI, 1019). The mean

prescribed antibiotic course was 19 days (95% CI, 1523).

Eight patients and 1 patient had transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiograms, respectively; none revealed vegetations. Ten (42%) patients encountered complications. Two

patients required incision and drainage of the PVC insertion

site, 3 patients developed complications related to antibiotic

therapy (Clostridium difficile colitis in 2 patients and 1 patient

with upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis related to the

peripherally inserted central catheter for intravenous antibiotics), 2 patients died, and 1 was discharged to hospice

care.

discussion

In our study, 12% of S. aureus catheter-related bacteremias

were due to PVCs, similar to 11% reported by others12 but

in contrast to another study that found an equal number of

S. aureus bacteremias due to PVCs and CVCs.13 Our study

reaffirms the substantial medical burden that arises from these

staphylococcus aureus bacteremia

581

table 2. Characteristics of Peripheral Venous Catheter (PVC)Related Staphylococcus aureus

Bacteremia Cases

Patient characteristics

Mean age, years (95% CI)

Female

Male

Clinical setting of PVC insertion

Emergency department

Inpatient medical unit

Rescue

Outside hospital

Anatomical site of PVC insertion

Right hand

Right antecubital area

Right forearm

Left hand

Left antecubital area

Left forearm

Clinical and microbiological characteristics

Mean duration of PVC insertion prior to PVCrelated S. aureus bacteremia, days (95% CI)

Mean visual infusion phlebitis score (95% CI)a

Yes

No

Definite

(n p 18)

Probable

(n p 6)

Total

(n p 24)

63 (5570)

5 (28)

13 (72)

65 (3595)

1 (17)

5 (83)

63 (5571)

6 (25)

18 (75)

13 (72)

4 (22)

1 (6)

0

3 (50)

0

1 (17)

2 (33)

16

4

2

2

(67)

(17)

(8)

(8)

1

10

3

0

3

1

(17)

(6)

0

1

2

1

2

0

(17)

(33)

(17)

(33)

1

11

5

1

5

1

(4)

(46)

(21)

(4)

(21)

(4)

3.8 (35)

3 (23)

7 (39)

11 (61)

4

3

1

5

(27)

(24)

(17)

(83)

4

3

8

16

(36)

(34)

(33)

(67)

(6)

(56)

(17)

note. Data are no. (%) unless otherwise indicated. CI, confidence interval.

a

Visual infusion phlebitis score: 1 pain or redness around insertion site; 2 pain, swelling,

redness, palpable venous cord; 3 pain, swelling, induration, redness, palpable venous cord beyond

3 cm, presence of pus; 4 all of the above and presence of tissue damage.

infections, as 42% of our patients with PVC-related S. aureus

bacteremia encountered complications.

More PVCs causing S. aureus bacteremia were placed in

the emergency department than PVCs in our point-prevalence survey, consistent with findings of emergent catheter

insertion increasing the risk of phlebitis14 and independently

increasing the risk of catheter colonization or local infection.15

A greater than expected number of PVC-related S. aureus

bacteremias involved catheters in the antecubital fossa, possibly related to an increased risk of phlebitis at this site16 and

cannulation of veins in areas of joint flexion.17 It is unknown

whether the antecubital fossa has a greater density of S. aureus

colonization than do other upper-extremity sites or whether

it is more difficult to maintain dressing placement at this site.

The median duration of time between PVC placement and

the first positive blood culture growing S. aureus was 3 days

(IQR, 36 days); however, 46% of patients with PVC-related

S. aureus bacteremia had a PVC duration greater than 3 days.

A meta-analysis suggests that changing PVCs every 3 days

does not reduce infection risk.18 However, in a national survey, in more than 90% of PVC-associated sepsis cases, the

PVC was in situ for 3 or more days,3 and there is an independent linear relationship between PVC infectious complications and dwell time.19 Thus, the meta-analysis may have

been underpowered to address the issue as a result of a small

number of catheters in place beyond 3 days and the low risk

of bloodstream infection.

We found 0.06 PVC-related S. aureus bacteremias per 1,000

catheter-days. The true incidence may have been underestimated because of our retrospective study design and the tendency for clinicians to overlook a PVC as a source for bacteremia. Another limitation of our study was the comparison

group, which was based on a 1-day point-prevalence survey;

as such, this may not have been a representative sample of

patients with uninfected PVCs.

Various hospital PVC care campaigns have reduced risk of

PVC infections. Intravenous nursing teams reduce the risk

of PVC infections,20-22 and this may relate to better compliance with relocating PVCs within 72 hours or within 24 hours

for emergently inserted PVCs.23 Insertion of a PVC after hand

hygiene with an alcohol waterless antiseptic or after donning

gloves is independently associated with lower risk of infectious complications.19 PVCs are often in situ, despite being

unused for 2 or more days,23,24 and quality improvement efforts can eliminate such idle catheters.24 Other interventions

can reduce the risk of such infections.25,26

PVC infections have been deemphasized, as most of our

national and local preventative efforts have focused on CVCs.

We documented 24 PVC-related S. aureus bacteremias involving 77,852 adult hospital discharges. There was a mean

582

infection control and hospital epidemiology

june 2011, vol. 32, no. 6

table 3. Comparison of Peripheral Venous Catheters (PVCs) Associated with Documented Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia and

PVCs without Associated Documented S. aureus Bacteremia

Anatomical site of PVC insertion

No. of PVCs

Hand

Antecubital area

Forearm

Location of PVC insertion

No. of patients with a PVC

Emergency department

Inpatient medical unit

Rescue

Outside hospital

Operating room or radiology

Unknown

Duration of PVC insertion

Median, days (IQR)

PVC-related S. aureus

bacteremia

PVC without S. aureus

bacteremiaa

24

2 (8)

16 (67)

6 (25)

317b

91 (29)

75 (24)

151 (48)

1.00

0.23

6.45

0.37

24

16

4

2

2

0

0

298

79

170

7

0

18

24

1.00

6.03

0.17

4.03

(67)

(17)

(8)

(8)

3 (36)

Exact odds ratio

(95% CI)

(reference)

(0.20.95)

(2.4718.02)

(0.121.00)

(6)

(8)

(reference)

(2.310.76)

(0.040.53)

(0.3822.76)

...

0 (03.06)

0 (02.19)

1 (12)

...

(27)

(57)

(2)

P valueb

.03

!.001

.03

!.001

!.001

.7

.005

.3

.4

!.001

note. Data are no. (%) unless otherwise indicated. CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range.

a

PVCs identified in a point-prevalence survey; some patients had more than 1 PVC.

b

Fischers exact test

of 32,529,144 adult patient discharges from US hospitals from

2005 through 2007.27 Thus, we estimate that there may be as

many as 10,028 PVC-related S. aureus bacteremias each year

in adults hospitalized in the United States. One study found

that having a PVC was independently associated with a lower

risk of S. aureus bacteremia.28 However, the risk posed by

PVCs must be viewed on a national scale since many patients

have a PVC during their hospital stay. Our study suggests

that hospitals should assess their risk of PVC-related infections and initiate interventions to mitigate risk if such infections are found. Minimizing PVC placement in the antecubital fossa, consideration for removing catheters within

24 hours if they were placed under emergent conditions, and

strong consideration for replacing PVCs after a 72-hour dwell

time will reduce risk of infection in adult patients.

acknowledgments

We appreciate the secretarial support of Nicole Lundstrom; the statistical

assistance of Jason Machan, PhD (Rhode Island Hospital and Warren Alpert

Medical School of Brown University); and the nurses who kindly carried out

the point-prevalence survey.

Financial support. This study had no external funding.

Potential conflicts of interest. L.A.M. has received research support from

Theravance and Pfizer and has served as a consultant for CorMedix, Ash

Access, Semprus, CareFusion, Bard, and Catheter Connections. None of these

activities involved peripheral intravenous catheters. All other authors report

no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Address correspondence to Leonard Mermel, DO, ScM, Division of Infectious Diseases, Rhode Island Hospital, 593 Eddy Street, Providence, RI

02903 (lmermel@lifespan.org).

references

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: central

lineassociated blood stream infectionsUnited States, 2001,

2008, and 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:243

248.

2. Maki DG, Kluger DM, Crnich CJ. The risk of bloodstream infection in adults with different intravascular devices: a systematic

review of 200 published prospective studies. Mayo Clinic Proc

2006;81:11591171.

3. Collignon PJ. Intravascular catheter associated sepsis, a common

problem: the Australian study on intravascular catheter-associated sepsis. Med J Aust 1994;161:374378.

4. Voges KA, Webb D, Fish LL, Kressel AB. One-day point-prevalence survey of central, arterial, and peripheral line use in adult

inpatients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009;30:606608.

5. Ritchie S, Jowitt D, Roberts S; and the Auckland District Health

Board Infection Control Service. The Auckland City Hospital

Device Point Prevalence Survey 2005: utilisation and infectious

complications of intravascular and urinary devices. N Z Med J

2007;120:U2683.

6. Pujol M, Hornero A, Saballs M, et al. Clinical epidemiology and

outcomes of peripheral venous catheter-related bloodstream infections at a university-affiliated hospital. J Hosp Infect 2007;67:

2229.

7. Zingg W, Imhof A, Maggiorini M, Stocker R, Keller E, Ruef C.

Impact of a prevention strategy targeting hand hygiene and

catheter care on the incidence of catheter-related bloodstream

infections. Crit Care Med 2009;37:21672173.

8. Hidron AI, Edwards JR, Patel J, et al, for the National Healthcare

Safety Network Team and Participating National Healthcare

Safety Network Facilities. NHSN annual update: antimicrobialresistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and

staphylococcus aureus bacteremia

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

Prevention, 20062007. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2008;29:

9961011.

Arnow PM, Quimosing EM, Beach M. Consequences of intravascular catheter sepsis. Clin Infect Dis 1993;16:778784.

Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med 1998;

339:520532.

Fowler VG Jr, Justice A, Moore C, et al. Risk factors for hematogenous complications of intravascular catheter-associated

Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:695

703.

Malanoski GJ, Samore MH, Pefanis A, Karchmer AW. Staphylococcus aureus catheter-associated bacteremia: minimal effective

therapy and unusual infectious complications associated with

arterial sheath catheters. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:11611166.

Thomas MG, Morris AJ. Cannula-associated Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: outcome in relation to treatment. Intern Med

J 2005;35:319330.

Larson E, Hargiss C. A decentralized approach to maintenance

of intravenous therapy. Am J Infect Control 1984;12:177186.

Goetz AM, Wagener MM, Miller JM, Muder RR. Risk of infection due to central venous catheters: effect of site of placement

and catheter type. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1998;19:842

845.

Adams SD, Killien M, Larson E. In-line filtration and infusion

phlebitis. Heart Lung 1986;15:134140.

Lavery I, Ingram P. Prevention of infection in peripheral intravenous devices. Nurs Stand 2006;20:4956.

Webster J, Osborne S, Rickard C, Hall J. Clinically indicated

replacement versus routine replacement of peripheral venous

catheters. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;3:CD007798.

Hirshmann H, Fux L, Podusel J, et al; and the European In-

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

583

terdisciplinary Committee for Infection Prophylaxis. The influence of hand hygiene prior to insertion of peripheral venous

catheters on the frequency of complications. J Hosp Infect 2001;

49:199203.

Tomford JW, Hershey CO, McLaren CE, Porter DK, Cohen DI.

Intravenous therapy team and peripheral venous catheterassociated complications: a prospective controlled study. Arch

Intern Med 1984;144:11911194.

Meier PA, Fredrickson M, Catney M, Nettleman MD. Impact

of a dedicated intravenous therapy team on nosocomial bloodstream infection rates. Am J Infect Control 1998;26:388392.

Soifer NE, Borzak S, Edlin BR, Weinstein RA. Prevention of

peripheral venous catheter complications with an intravenous

therapy team: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med

1998;158:473477.

Lederle FA, Parenti CM, Berskow LC, Ellingson KJ. The idle

intravenous catheter. Ann Intern Med 1992;116:737738.

Parenti CM, Lederle FA, Impola CL, Peterson LR. Reduction of

unnecessary intravenous catheter use: internal medicine house

staff participate in a successful quality improvement project.

Arch Intern Med 1994;154:18291832.

Aziz AM. Improving peripheral IV cannula care: implementing

high-impact interventions. Br J Nurs 2009;18:12421246.

OGrady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for the

prevention of intravascular catheter-related infection. Clin Infect

Dis 2011;52:e162e193.

AHRQ. National Inpatient Sample. http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov. Accessed April 12, 2010.

Stryjewski ME, Kanafani ZA, Chu VH, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia among patients with health care-associated fever.

Am J Med 2009;122:281289.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Matchstick MenDocument9 pagesMatchstick Menmichael_arnesonNo ratings yet

- Cancer of Oral CavityDocument27 pagesCancer of Oral CavityMihai AlexandruNo ratings yet

- The Tuskegee Syphilis StudyDocument11 pagesThe Tuskegee Syphilis Studyapi-285171544No ratings yet

- Aesthetic Jurnal PDFDocument20 pagesAesthetic Jurnal PDFTarrayuanaNo ratings yet

- 1000 Days Ni Baby PDFDocument31 pages1000 Days Ni Baby PDFppantollanaNo ratings yet

- Sfbtnarr 2Document19 pagesSfbtnarr 2api-267074391No ratings yet

- Congenital Syphilis Causes and TreatmentDocument4 pagesCongenital Syphilis Causes and TreatmentAlya Putri Khairani100% (1)

- Practicing The A, B, C'S: Albert Ellis and REBTDocument24 pagesPracticing The A, B, C'S: Albert Ellis and REBTShareenjitKaurNo ratings yet

- MNA EnglishDocument1 pageMNA Englishdidik hariyadiNo ratings yet

- Registered Dietitians in Primary CareDocument36 pagesRegistered Dietitians in Primary CareAlegria03No ratings yet

- NM ObtDocument22 pagesNM ObtIlyan NastiNo ratings yet

- Huckstep Nail For Periimplant FractureDocument3 pagesHuckstep Nail For Periimplant FracturePurushothama Rao NalamatiNo ratings yet

- Brand Name Generic Name Disease Group Consumer Medicine Information More InfoDocument9 pagesBrand Name Generic Name Disease Group Consumer Medicine Information More InfoBairavi RathakrishnanNo ratings yet

- M5W Wang FeedbackDocument21 pagesM5W Wang FeedbackIsaac HassanNo ratings yet

- Magnetic StimulationDocument5 pagesMagnetic StimulationMikaelNJonssonNo ratings yet

- Twins Bootcamp StudyDocument5 pagesTwins Bootcamp Studyandi dirhanNo ratings yet

- علاجDocument5 pagesعلاجabramNo ratings yet

- Lymphatic Drainage 101Document6 pagesLymphatic Drainage 101Vy HoangNo ratings yet

- Country Presentation: CambodiaDocument11 pagesCountry Presentation: CambodiaADBI Events100% (1)

- Drugs in PregnancyDocument14 pagesDrugs in Pregnancyhenry_poirotNo ratings yet

- Case Report in Psychiatry051.03Document4 pagesCase Report in Psychiatry051.03Christian Tan Getana100% (1)

- Puyer Asthma and Diare Medication DosagesDocument1 pagePuyer Asthma and Diare Medication DosagesAlbert SudharsonoNo ratings yet

- Aromatherapy PRDocument1 pageAromatherapy PRNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilNo ratings yet

- Types of PsychologyDocument62 pagesTypes of PsychologyParamjit SharmaNo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet for Masterseal 345Document7 pagesSafety Data Sheet for Masterseal 345mkashkooli_scribdNo ratings yet

- Ethical PrinciplesDocument2 pagesEthical PrinciplesyoonjessNo ratings yet

- Wound AssessmentDocument19 pagesWound Assessmentdrsonuchawla100% (1)

- Gestalt PsychotherapyDocument2 pagesGestalt PsychotherapyAnson AtilanoNo ratings yet

- Psychotherapeutic Traditions HandoutDocument5 pagesPsychotherapeutic Traditions HandoutTina Malabanan CobarrubiasNo ratings yet

- A Case Study For Electrical StimulationDocument3 pagesA Case Study For Electrical StimulationFaisal QureshiNo ratings yet