Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nutrition and Fluid Balance Must Be Taken Seriously

Uploaded by

Paola RincónCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nutrition and Fluid Balance Must Be Taken Seriously

Uploaded by

Paola RincónCopyright:

Available Formats

BMJ 2013;346:f801 doi: 10.1136/bmj.

f801 (Published 8 February 2013)

Page 1 of 5

Analysis

ANALYSIS

Nutrition and fluid balance must be taken seriously

Richard Leach and colleagues explain why ensuring adequate nutrition and hydration makes both

clinical and financial sense and requires the attention of everyone involved in healthcare

1

Richard M Leach chair, Royal College of Physicians nutrition committee , Ailsa Brotherton honorary

2

secretary, British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition , Michael Stroud chair, NICE fluid

3

4

guideline committee , Richard Thompson president

Guys and St Thomas NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK; 2NHS Quest, Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Salford, UK ; 3Gastroenterology

and Nutrition, Southampton University Hospitals NHS Trust, Southampton, UK; 4Royal College of Physicians, London, UK

1

Provision of appropriate nutrition and hydration is a hallmark

of compassionate care but is often neglected in all types of

healthcare.1-5 These problems are not new and have been reported

in the medical literature for nearly four decades.6 7 The

consequences are clinically and financially costly. The estimated

excess UK health related costs of malnutrition are at least 13bn

(15bn; $20bn) annually.1

Patients with malnutrition have a deficit of energy, protein,

vitamins, or minerals, and this has measurable adverse effects

on the body.2 Those at risk include patients with poor intake or

appetite, dysphagia, chronic disease, or poor functional and

social or cognitive ability. Defining adequate hydration is

complex. It is estimated by the synthesis of clinical indicators

(such as confusion, tachycardia, blood pressure, and thirst),

serum biochemistry (such as urea and creatinine), tissue

perfusion markers (such as urine output, lactate levels), and

urine specific gravity. We examine the scale of malnutrition

and poor hydration in our hospitals and communities, explain

why it matters, and put forward proposals for change.

Big problem with bad press

The UK national nutrition surveys estimate that over three

million people are either malnourished or at risk of malnutrition,

of whom more than 90%, or 2.7 million, are cared for in the

community (box 1).1 2 3 5 8 One in three patients admitted to

hospital or a care home, and one in five of those admitted to

mental health facilities were malnourished or at risk of

malnutrition, according to four national surveys (31 646 people

admitted to hospital, 3404 to care homes, and 1206 to mental

health facilities).8 Nutritional status often declines further after

admission to hospital because acute illness or injury can impair

appetite, swallowing, and intestinal absorption. Similar problems

occur in other countries.2 9 10

The health ombudsman for England, Ann Abraham, found a

lack of access to fresh drinking water and inadequate help with

eating in half of cases during her investigations into care of

older people.11 She described this as incomprehensible and said

that everybody working in the NHS, including doctors, nurses,

managers, and chief executives, had a responsibility to deliver

adequate fluid and nutrition. Her findings are not isolated.12 13

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) reported that just 51 of

100 acute NHS hospitals fully complied with their standards

for meeting patients nutritional needs.12 The commissions

dignity and nutrition report on the inspection of 500 care homes

in 2012 is currently awaited.12 Age UKs campaign Hungry to

be heard and the Patients Association report Malnutrition in

the Community and Hospital Setting both indicate inadequate

provision of easily accessible food and hydration in all types of

healthcare facility.5 13

Importance of nutrition and fluid

management

Malnutrition is associated with increased morbidity and

mortality in acute and chronic diseases.1-3 Complications

associated with malnutrition can arise within days in people

with little or no nutritional intake and may precede significant

weight loss.

In wound healing, malnutrition prolongs the inflammatory phase,

decreases fibroblast proliferation, alters collagen synthesis, and

ultimately reduces wound tensile strength.14 Consequently,

malnutrition is associated with increased risk of pressure ulcers,

delayed wound healing, wound infections, and chronic

non-healing wounds. Malnutrition also impairs the immune

system by suppressing cell mediated immunity, complement

systems, phagocyte function, cytokine production and antibody

response and affinity.15 In an observational study, hospital

inpatients identified as high risk by the nutritional risk index

were at three times the risk of nosocomial infection compared

with similar patients who were well nourished.16 Malnutrition

is associated with a twofold to threefold increased risk of

postoperative complications.1 2 8 10

Correspondence to: R M Leach richard.leach@gstt.nhs.uk

For personal use only: See rights and reprints http://www.bmj.com/permissions

Subscribe: http://www.bmj.com/subscribe

BMJ 2013;346:f801 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f801 (Published 8 February 2013)

Page 2 of 5

ANALYSIS

Box 1: Prevalence of malnutrition in UK1-3 5 8

Home

General population (adults):

Body mass index <20=5%

Body mass index <18.5=1.8%

People over 65=14%

Sheltered housing

10-14% of residents

Hospital

25-34% of admissions

Care homes

30-42% of recently admitted residents

Malnutrition also affects patients admitted to hospital with

conditions such as stroke, pressure ulcers, or falls. Increased

morbidity secondary to malnutrition prolongs hospital stay by

an average of three days and increases readmission rates by up

to 50%.1-5 9 10 The effect of poor nutrition is particularly severe

in older people.

Chronic malnutrition is associated with frailty, unintentional

weight loss, weakness, immobility, sarcopenia, and poor

endurance. Those who are malnourished visit their general

practitioner twice as often as the well nourished and are three

times more likely to be admitted to hospital, irrespective of

other conditions.4 They also experience more complications and

higher death rates in all age groups and disease categories.1-5 9 10

People who are risk of malnutrition also seem to experience

adverse outcomes. For example, in a recent, large multicentre

study (n=5051) in 12 countries and 26 hospital departments,

patients at risk of malnutrition had a 12-fold increase in hospital

mortality.10

Dehydration and overhydration are well recognised causes and

consequences of illness and injury. The association between

intravenous fluid overload and subsequent morbidity and

mortality is rarely recognised by regulatory authorities because

of the difficulty in attributing cause and effect. Overhydration

manifested as pulmonary oedema is a common consequence of

excessive intravenous fluids. Pulmonary oedema can be rapidly

corrected with diuretic therapy. However, the pneumonia that

may follow may not be considered a fluid related complication

and is rarely reported. In postoperative patients fluid

mismanagement has been documented in 17-54% of cases and

contributes to about 9000 deaths annually in the United

States.17-19

Improving malnutrition and poor fluid management makes

financial as well as clinical sense.20 The National Institute for

Health and Clinical Excellence has identified improvements in

nutritional care as the fourth largest potential source of NHS

savings.2 A malnourished patient costs the NHS 2000 a year.10

The cost of poor fluid management has not been established.

However, it may be considerable if problems such as acute

kidney injury from avoidable dehydration are added to those

related to excess fluid administration (pulmonary oedema, post

surgical ileus, wound breakdown, etc).17 18

Mismatch between guidance and reality

NICE has issued clear guidance on nutritional screening, dietary

requirements, and care of people identified as at risk (box 22).

However despite the scale and impact of poor nutrition and

hydration these standards are often not met. Many factors may

For personal use only: See rights and reprints http://www.bmj.com/permissions

contribute to poor implementation, such as poor training, lack

of time, competing tasks, and a perception that basic care is less

important than others duties or the responsibility of others (box

3).

Screening

The first job is to identify people who may be malnourished. In

the UK 93% of those who are malnourished, or at risk of

malnutrition, are living in their own homes, and 5% are in care

homes. NICE guidelines state that GPs should screen all

patients nutrition on registration, care homes should screen

people on enrolment, and hospitals at the first outpatient

appointment. However, two thirds of the patients admitted to

hospital who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition come

directly from their own home, suggesting the need for improved

recognition and management of nutritional problems in the

community.

The remaining 2% of those who are malnourished or at risk of

malnutrition are in hospital. Admission to hospital provides a

vital opportunity to identify malnutrition and initiate treatment,

which can then be continued in the community after discharge.

The NICE guidelines suggest that adults nutritional status

should be screened on admission to hospital. Most hospitals

recognise that screening with validated nutritional tools such

as the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool should be part of

basic clinical care,1-3 21 but many lack robust systems to ensure

it is done or the results acted on.

Recognition

In hospital, poor documentation of fluid balance and nutritional

intake contributes to morbidity and mortality.17 18 22-25 Less than

half of fluid balance sheets are completed adequately, and in

complex cases, electrolyte (biochemical) monitoring is often

poor.17 18 25 One in three nurses does not feel competent to

recognise or treat malnutrition or fluid management.12

Appropriate treatment

Assuming the patient can swallow safely, the first step is to

maximise normal food intake with a balanced mixture of protein,

energy, fibre, electrolytes, vitamins, and minerals. Despite

substantial improvements, some hospitals and care homes

continue to offer unsuitable menus with insufficient provision

for food preferences, ethnic and religious needs, or portion

sizes.2 5 13

A different approach may be needed for patients who have lost

their appetite. Cochrane meta-analysis shows little or no benefit

from dietetic intervention for malnutrition accompanying acute

Subscribe: http://www.bmj.com/subscribe

BMJ 2013;346:f801 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f801 (Published 8 February 2013)

Page 3 of 5

ANALYSIS

Box 2: Key NICE recommendations on nutrition support in adults2

Screening for malnutrition or the risk of malnutrition should be carried out by healthcare professionals with appropriate skills and

training

All hospital inpatients should be screened on admission and all outpatients at their first clinic appointment. Screening should be

repeated weekly for inpatients and, when there is clinical concern, for outpatients. People in care homes should be screened on

admission and when there is clinical concern

Nutrition support should be considered in people who are malnourished, as defined by any of the following:

Body mass index (BMI) <18.5

Unintentional weight loss greater than 10% within past 3-6 months

BMI <20 and unintentional weight loss greater than 5% in the last 36 months.

People who have eaten little or nothing for more than 5 days or are likely to eat little or nothing for the next 5 days or longer

People who have a poor absorptive capacity, high nutrient losses, or increased nutritional needs from causes such as catabolism

Box 3: Barriers to improving nutritional and fluid care

Lack of education for frontline staff on the importance of nutrition and hydration care coupled with poor attitudes and lack of respect

for vulnerable, often elderly patients

Failure of acute trusts to implement 2006 NICE guidance on nutrition steering committees and multidisciplinary nutrition support team

with at least one specialist nutrition support nurse to minimise complications from enteral tube and intravenous nutrition

Reluctance of practitioners, health service managers, and professional groups to accept responsibility for setting polices and standards

at local or national levels

Multiple malnutrition guidelines and initiatives that may add confusion rather than clarity

Some misleading research and public advice causing both professional and public scepticism about nutritional standards

Lack of research on fluid management beyond highly specialised settings and lack of specific guidance on general fluid prescribing

illness. Oral nutritional supplements, often referred to as build

up drinks, may help in the short term.1-3 A Cochrane

meta-analysis of 42 randomised controlled trials of oral

supplements versus standard care in malnourished elderly

hospital patients showed a mean 2.2% increase in weight (95%

confidence interval 1.8 to 2.5) and reductions in a composite

outcome of complications such as infection, deep vein

thrombosis, and pressure sores (relative risk 0.86, 0.75 to 0.99).26

The use and prescription of short term oral nutritional

supplements is variable and controversial in the UK because of

perceived recent rapid increases in their costs and reported

inappropriate use and wastage. Properly planned nutritional care

should reduce inappropriate use and improve individual patient

outcomes. Although demand (and associated expenditure on

supplements ) is likely to increase, the overall treatment costs

should fall significantly.1-3 27

When oral nutrition is not possible or is inadequate, enteral tube

feeding and/or intravenous nutrition are necessary. Both methods

carry risk. In 2009-10, 41 never events were reported to the

National Patient Safety Agency, where a misplaced nasogastric

or orogastric tube was not detected before use.28 The National

Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death

(NCEPOD) found that 81% of patients receiving intravenous

nutrition did not receive quality care, characterised by thorough

assessment, appropriate intravenous feed, safe intravenous

access, and electrolyte monitoring, delivered by a trained team.29

There are also problems with prescribing and delivering fluids.4

Volumes and types of fluid prescription are often

inappropriate.17 24 For example, in studies in postoperative

patients there was little correlation between fluid and electrolytes

prescription and preoperative weight, serum electrolyte levels,

or ongoing fluid losses.17 Only 26% of intravenous fluid

prescriptions were administered at the prescribed rate; 67%

were infused too slowly and 8% too fast.24 Lack of routine and

careful fluid assessment during ward rounds led by senior

clinicians and pharmacists is likely to play a part. Decisions

may be left until out of hours periods, when junior doctors must

prescribe fluids for patients they do not know, although formal

evidence for this is lacking.

For personal use only: See rights and reprints http://www.bmj.com/permissions

Junior clinicians and nursing staff lack basic knowledge about

nutritional care and fluid and electrolyte management. Half of

new foundation doctors lack the basic knowledge to prescribe

perioperative fluid safely.22 25 30 31 Less than half of trainees know

the sodium content of 0.9% saline, suggesting that many do not

know the normal daily fluid and electrolyte maintenance

requirements, or use this knowledge in daily fluid management

practice, a suspicion supported by audit data.25 Although the

curriculums for undergraduate and foundation doctor training

include the essential information for safe fluid prescription, it

is often piecemeal, rarely consolidated to provide practical

guidance, and competency is not robustly monitored.22 This is

because such core general education aligns poorly with specialist

training programmes and is often considered less important.19 22

Way forward

Considerable, but uncoordinated, efforts have been made to

provide high quality guidance on solving these problems, with

over 20 initiatives, guidelines, quality standards, and nutritional

indicators published in service frameworks commissioning

guidelines since 2000.1 5 Yet there has been a failure to translate

this knowledge into high quality care and nutritional and fluid

management standards.

One reason seems to be the haphazard and variable adoption of

the plethora of available and potentially confusing guidelines.

This suggests a need for central responsibility and

coordination of implementation, monitoring, and choice of the

most cost effective services. The second important issue has

been lack of appreciation, engagement, and education of

patients, carers, healthcare professionals, managers,

commissioners, and government executives about the importance

of nutrition and hydration in terms of healthcare outcomes,

service use, and NHS costs.

Delivery of quality, comprehensive, patient focused, nutritional

and fluid care requires a coordinated, uniform and monitored

approach from government, organisations, managers, clinical

staff, and the public (box 4). Communication between these

Subscribe: http://www.bmj.com/subscribe

BMJ 2013;346:f801 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f801 (Published 8 February 2013)

Page 4 of 5

ANALYSIS

groups should be clear and effective. Achieving these goals

requires change.

Central leadership and responsibility

The government must make adequate nutrition a priority for the

National Commissioning Board, as well as public health policies.

European health providers have committed to tackling these

problems, and the malnutrition task force in England is working

to ensure implementation of good nutritional care for all older

people.

Policy change and development

The new Health and Social Care Act is not clear how

cross-cutting clinical themes, like nutrition and fluid

management, should be addressed in national policy. This needs

to be corrected.

Clinical commissioning groups should consider appointing

executive leads responsible for good nutritional care. The British

Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN) has

produced a toolkit for commissioners and providers to help them

deliver high quality nutritional care and fluid management

services.3

Professional bodies and other organisations

A coordinated approach from professional bodies and charities

is needed to implement a uniform, coordinated nutrition strategy.

BAPEN is working to facilitate this.

Implement current guidelines

Many guidelines exist to improve the quality of nutritional

care.1-3 5 Implementation of NICE nutrition guidance would save

clinical commissioning groups about 28 500/100 000

population every year.21 Various monitoring and audits systems

are available to enable organisations to document achievement

of key targets and key performance indicatorsfor example,

nutrition dashboards and the patient environment action teams

annual assessments.32

Senior clinicians and managers must take

responsibility

Perceived lack of interest of senior clinicians to engage with

nutritional issues often has a detrimental effect on the views of

the wider medical team. Nutrition and hydration should not be

delegated to junior clinicians. Teams must develop an approach

to dealing routinely with fluid management and nutritional care

on ward rounds despite competing demands. Simple measures

such as ward round checklists may improve fluid management

and nutrition.33

Identifying who is responsible and accountable for nutrition

and hydration at an organisational level is necessary but

challenging. It will involve coordination of different professional

groups, departments, and organisations. Many organisations do

not have senior clinicians or executives with responsibility for

nutrition and hydration. The emphasis on nutrition and hydration

must extend from board rooms and into the wards, clinics, and

community services.

Every trust should have reliable systems within its management

and governance frameworks to ensure delivery of high quality

nutrition and fluid management targets. This should include a

multidisciplinary nutrition support team that reports to a nutrition

steering committee. An identified senior clinician should act as

the trusts nutrition champion. The NICE quality standards

released in 2012 should facilitate delivery of better nutritional

For personal use only: See rights and reprints http://www.bmj.com/permissions

care, including the required nutrition screening and care planning

standards.34 NICE guidance and quality standards on intravenous

fluid prescribing are also due in 2013. Future development of

realistic and achievable key performance indicators may be

needed.

Education for staff, patients, and carers

Medical and nursing graduates need minimum levels of

competence in nutrition and fluid management, such as those

developed by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges

Intercollegiate Group on Nutrition.34 Basic principles of

nutritional care and intravenous fluid prescription must be

embedded in general and specialty training programmes. Some

e-learning materials are already available. The Royal College

of Physicians has raised the importance of improving general

medical training on vital core medical competencies (including

fluid management and nutrition) that are often neglected in

current specialty training programmes.

In a busy ward environment it is easy to overlook the basic

requirements of humane, compassionate care. Staff should

ensure food and fresh drink are within easy reach and that

mealtimes are protected. Red trays can act as a visible indicator

to all staff of vulnerable or malnourished patients who need

additional support with eating and careful monitoring of food

intake. Relatives should be allowed access to the wards to help

at mealtimes when feeding is a problem.

The importance of educating patients and carers in optimal

nutrition is often overlooked and can be addressed at the bedside,

in consulting rooms, and through educational material such as

leaflets. Relatives often appreciate the opportunity to help with

this vital and intimate aspect of care.

Time to act

Now is the time to take fluid and nutrition seriously, not only

within hospitals but also in care homes and the community.

Failure to address these essential but often complex issues has

profound, often avoidable effects on morbidity and mortality

and results in unnecessary costs.

Contributors and sources: RML is a consultant physician and intensivist

and is a previous member and current chair of the RCP nutrition

committee. AB was a clinical dietitian and senior research fellow before

developing an interest in improvement science. MS is a senior lecturer

and consultant gastroenterologist and previous chair of BAPEN. He has

extensive experience in clinical nutrition, research, and guideline

development and has reported widely on implementation of good

nutritional care. RT is a professor and consultant gastroenterologist,

now president of the RCP. This article arose from discussions arising

at the RCP nutrition committee following high profile media reports of

failure to deliver appropriate standards of fluid management and

nutritional care in hospitals.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ Group

policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to

declare.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer

reviewed.

1

2

3

Elia M, Russell CA. Combating malnutrition; recommendations for action. A report from

the advisory group on malnutrition. BAPEN, 2009.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Nutrition support in adults. Clinical

Guideline 32. 2006. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG32.

Brotherton A, Simmonds N, Stroud M, BAPEN Quality Group. Malnutrition matters. Meeting

quality standards in nutritional care. A toolkit for commissioners and providers in England.

2010. www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/toolkit-for-commissioners.pdf.

Subscribe: http://www.bmj.com/subscribe

BMJ 2013;346:f801 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f801 (Published 8 February 2013)

Page 5 of 5

ANALYSIS

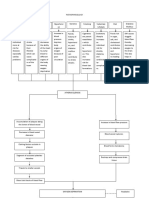

Box 4: How to improve nutritional and fluid management

Government

Include nutritional care in its mandate to the National Commissioning Board

Appoint a senior leader with overall responsibility for nutrition

Department of Health

Embed nutritional care into policy

Appoint a national clinical director for nutrition and hydration

Use the appropriate system levers to incentivise providerseg, national commissioning for quality and innovation targets

Regions and clinical commissioning groups

Appoint executive leads for nutrition

Take responsibility for commissioning nutritional care

Include in contracts and national targets

Acute trust and providers

Reliable systems, with nutrition steering committees and nutrition support teams

Education for all frontline staff

Ensure nutrition screening and planned care

Patients and public

Increased awareness of malnutrition

Self management

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Guest JF, Panca M, Baeyens JP, de Man F, Ljungqvist O, Pichard C, et al. Health

economic impact of managing patients following a community-based diagnosis of

malnutrition in the UK. Clin Nutr 2011;30:422-9.

Patients Association. Malnutrition in the community and hospital setting. PA, 2011.

Bistrian BR, Blackburn GL, Vitale J, Cochran D, Naylor J. Prevalence of malnutrition in

general medical patients. JAMA 1976;235:1567-70.

McWhirter JP, Pennington CR. Incidence and recognition of malnutrition in hospital. BMJ

1994;308:945.

Russell CA, Elia M. Nutritional screening survey in the UK and Republic of Ireland 2011.

www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/nsw/nsw-2011-report.pdf.

Stratton RJ, Green CJ, Elia M. Disease-related malnutrition: an evidence based approach

to treatment. CABI, 2003.

Sorensen J, Kondrup J, Prokopowicz J, Schiesser M, Krahenbuhl L, Meier R et al.

EuroOOPS: an international, multicentre study to implement nutritional risk screening and

evaluate clinical outcome. Clin Nutr 2008;27:340-9.

Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman. Care and compassion? Report of the

health service ombudsman on ten investigations into NHS care of older people. 2011.

www.ombudsman.org.uk/care-and-compassion.

Care Quality Commission. National report on dignity and nutrition. CQC, 2011. www.cqc.

org.uk/public/reports-surveys-and-reviews/themes-inspections/dignity-and-nutrition-olderpeople.

Age UK. Still hungry to be heard. The scandal of people in later life becoming malnourished

in hospital. Age UK, 2010.

Stechmiller JK. Understanding the role of nutrition and wound healing . Nutr Clin Pract

2010;25:61-8.

Marcos A, Nova E, Montero A. Changes in the immune system are conditioned by nutrition.

Eur J Clin Nutr 2003;57(suppl 1):S669.

Schneider SM, Veyres P, Pivot X, Soummer AM, Jambou P, Filippi J, et al. Malnutrition

is an independent factor associated with nosocomial infections. Br J Nutr 2004;92:105-11.

Walsh SR, Walch CJ. Intravenous fluid associated morbidity in postoperative patients.

Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2005;87:126-30.

Walsh SR, Cook EJ, Bentley R, Farooq N, Gardner-Thorpe J, Tang T, et al. Peri-operative

fluid management: prospective audit. Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:492-7.

Arieff AI. Fatal postoperative pulmonary edema: pathogenesis and literature review. Chest

1999;115:1371-7.

NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. High impact actions for nursing and

midwifery. 2009. www.institute.nhs.uk/images//stories/Building_Capability/HIA/NHSI%

20High%20Impact%20Actions.pdf.

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

NICE. Cost saving guidance. 2009. www.nice.org.uk/usingguidance/

benefitsofimplementation/costsavingguidance.jspwww.nice.org.uk/usingguidance/

benefitsofimplementation/costsavingguidance.jsp.

Powell AGMT, Paterson-Brown S. FY1 doctors still poor in prescribing intravenous fluids.

BMJ 2011;342:d2741.

Callum KG, Carr NJ, Gray AJG, Hargreaves CMJ, Hoile RW, Ingram GS, et al. The 2002

report of the national confidential enquiry into perioperative deaths. www.ncepod.org.uk/

pdf/2002/02full.pdf.

Rooker JC, Gorard DA. Errors of intravenous fluid infusion rates in medical inpatients.

Clin Med 2007;7:482-5.

Powell-Tuck Jeremy, Gosling P, Lobo DN, Allison SP, Carlson GL, Gore M, et al. British

consensus guidelines on intravenous fluid therapy for adult surgical patients. 2011. www.

bapen.org.uk/pdfs/bapen_pubs/giftasup.pdf.

Milne AC, Potter J, Vivanti A, Avenell A. Protein and energy supplementation in elderly

people at risk from malnutrition. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2:CD003288.

Elia M, Startton R, Russell C, Green C, Pang F. The cost of disease-related malnutrition

in the UK and economic considerations for the use of oral nutritional supplements. BAPEN,

2005.

National Patient Safety Agency. Reducing harm caused by the misplacement of nasogastric

feeding tubes. www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?entryid45=59794www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/

resources/?entryid45=59794

NCEPOD. Artificial nutrition enquiry report: a mixed bag. 2010.

www.ncepod.org.uk/2010pn.htm.

Tang VCY, Lee EWY, Fluid balance chart: do we understand it? Clin Risk 2010;16:10-3.

National Patient Safety Agency patient environment action teams (PEAT). 2010. http://

www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/patient-safety-data/peat/.

Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of Nursing. Ward rounds in medicine. 2012.

www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/ward-rounds-in-medicine-web.pdf.

Soong J, Bravis V, Smith D, LeBall K, Levy J. Improving ward round processes: a pilot

medical checklist improves performance. Paris: International Forum on Quality and Safety

in Healthcare, 2012.

Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. UNEIG undergraduate curriculum . www.aomrc.org.

uk/committees/item/curricula.html.

Accepted: 1 December 2012

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:f801

BMJ Publishing Group Ltd 2013

For personal use only: See rights and reprints http://www.bmj.com/permissions

Subscribe: http://www.bmj.com/subscribe

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Barack Huessein Obama Is The Most Dangerous Man To Ever LiveDocument3 pagesBarack Huessein Obama Is The Most Dangerous Man To Ever LivetravisdannNo ratings yet

- Drugs & Cosmetics ActDocument70 pagesDrugs & Cosmetics ActAnonymous ibmeej9No ratings yet

- Failures in Periodontal Therapy: Review ArticleDocument6 pagesFailures in Periodontal Therapy: Review ArticlezinniaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy Math CalculationsDocument8 pagesPharmacy Math CalculationsRahmawati KuswandiNo ratings yet

- Recurrent Gingival Cyst of Adult: A Rare Case Report With Review of LiteratureDocument5 pagesRecurrent Gingival Cyst of Adult: A Rare Case Report With Review of Literaturesayantan karmakarNo ratings yet

- Drug Hypersensitivity & Drug Induced DiseasesDocument23 pagesDrug Hypersensitivity & Drug Induced DiseasesBella100% (1)

- Hospital ICU Organization and TypesDocument82 pagesHospital ICU Organization and TypesPaul Shan GoNo ratings yet

- Mu 089Document4 pagesMu 089Rahul RaiNo ratings yet

- Blessing IwezueDocument3 pagesBlessing Iwezueanon-792990100% (2)

- Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities ofDocument6 pagesAntibacterial and Antifungal Activities ofSamiantara DotsNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology Tia VS CvaDocument6 pagesPathophysiology Tia VS CvaRobby Nur Zam ZamNo ratings yet

- A Study of Demographic Variables of Violent Asphyxial Death: JPAFMAT, 2003, Vol.: 3 ISSN - 0972 - 5687Document4 pagesA Study of Demographic Variables of Violent Asphyxial Death: JPAFMAT, 2003, Vol.: 3 ISSN - 0972 - 5687Reza ArgoNo ratings yet

- Kayachikitsa Paper 1 PDFDocument24 pagesKayachikitsa Paper 1 PDFMayura JainNo ratings yet

- Anggi Retno Wardani - 40121064Document91 pagesAnggi Retno Wardani - 40121064febyNo ratings yet

- Reversal of Fortune: The True Story of Claus von Bülow's Conviction and Alan Dershowitz's Innovative DefenseDocument9 pagesReversal of Fortune: The True Story of Claus von Bülow's Conviction and Alan Dershowitz's Innovative Defensetamakiusui18No ratings yet

- Bioactive Compounds in Phytomedicine BookDocument228 pagesBioactive Compounds in Phytomedicine BookAnil KumarNo ratings yet

- Hospital List 06052016Document5 pagesHospital List 06052016Azhar ThireiNo ratings yet

- SOCA Blok 12Document21 pagesSOCA Blok 12safiraNo ratings yet

- Guppy Brain Atlas SmallerDocument4 pagesGuppy Brain Atlas Smallerapi-394354061No ratings yet

- Minha Biblioteca Catalogo Julho 2022 Novos TitulosDocument110 pagesMinha Biblioteca Catalogo Julho 2022 Novos TitulosMarcelo SpritzerNo ratings yet

- Klinefelter SyndromeDocument6 pagesKlinefelter Syndromemeeeenon100% (1)

- Gold Foil: Safety Data SheetDocument4 pagesGold Foil: Safety Data SheetSyawatulshuhada SyawalNo ratings yet

- The Herbal Market of Thessaloniki N GreeDocument19 pagesThe Herbal Market of Thessaloniki N GreeDanaNo ratings yet

- VMC Customer Service Complaint and Letter of DemandDocument3 pagesVMC Customer Service Complaint and Letter of DemandJames Alan BushNo ratings yet

- Siddha Therapeutic Index - 18-Article Text-133-1-10-20210308Document7 pagesSiddha Therapeutic Index - 18-Article Text-133-1-10-20210308Dr.kali.vijay kumkarNo ratings yet

- Datex-Ohmeda Aespire 7900 - Maintenance and Troubleshooting PDFDocument118 pagesDatex-Ohmeda Aespire 7900 - Maintenance and Troubleshooting PDFJosé Morales Echenique100% (1)

- Anaesthesia - 2020 - Griffiths - Guideline For The Management of Hip Fractures 2020Document13 pagesAnaesthesia - 2020 - Griffiths - Guideline For The Management of Hip Fractures 2020BBD BBDNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology For Nurses by Diane Pacitti Blaine T. SmithDocument570 pagesPharmacology For Nurses by Diane Pacitti Blaine T. SmithJessica Anis0% (1)

- Medic Alert Short BrochureDocument2 pagesMedic Alert Short BrochureDerek DickersonNo ratings yet

- Breast Assessment Learning ObjectivesDocument6 pagesBreast Assessment Learning Objectivesalphabennydelta4468No ratings yet