Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MANDUŠIĆ NEW Slavic Forum 2009

Uploaded by

Zdenko MandušićCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

MANDUŠIĆ NEW Slavic Forum 2009

Uploaded by

Zdenko MandušićCopyright:

Available Formats

ZdenkoMandui

HowFormalistsWatchedFilm:Shklovsky,Pudovkin,andTheEndofSt.Petersburg

DeclaredbysometobeVsevolodPudovkinsmostcomplexandmultifariousfilm(Kepley,2),

The End of St. Petersburg (1927) represents a curious combination of disparate cinematic

strategies,whichreflecttheculturaltensionsthatinfluencedthefilmsproduction.Pudovkins

epicwascommissionedforthetenthanniversaryoftheOctoberRevolutionandismadeof

episodicrenderingsofbothmundanehumanactivitiesandepicscaleactionsequencesdepicting

warandrevolution.ItcombinesHollywoodinspiredclassicalcontinuityeditingwithRussian

avantgarde montage. In this manner, the film represents Pudovkins investment in multiple

cinematicstrategies.Eventhoughithasbeensubsequentlyanointedacinematicmasterpiece,the

filmwasnotoriginallywellreceivedbythepublicandsomereviewersdebatedthecombination

ofvaryingcinematicelements.Writinginthe1927yearendissueoftheNovyiLefjournal,

VictorShklovskyclaimedPudovkinsfilmhadanambivalenteffectonhim(1988,180).But

whileShklovskycriticizesthefilmforhavingaweaknarrative,healsoconsiderschallengesof

poeticcinemaandproblemsofmontage,commendingPudovkinsuseofpoeticmontageandhis

experimentationwiththecleansedshot.

SincetheconceptsunderpinningShklovskysreadingofPudovkinsfilmareassociated

withtheworkofRussianFormalistsonliteratureandcinema,theNovyiLefarticlebelongsto

thewidercriticalcontextof1920sSovietArtandFilm.ButInsteadofconfirmingearlierheld

views regarding the limits and possibilities of film, Shklovsky departs from his developed

stancesontheprimacyofplotincinemabyhisopennesstostylisticcontrolofplotconstruction,

Mandui2

withwhichPudovkinresolvedthenarrativeproblemofsituatingindividualexperienceswithin

theepiccontextoftheRevolution.ThispaperwillcontrastShklovskyscriticalstanceregarding

TheEndofSt.Petersburg toPudovkinsownconceptions offilmmaking,inordertobetter

understandthecriticaldiscourseandtheinterconnectedconceptionsoffilmmakingandnarrative

thatshapedthisepiccommemorationoftheRevolution.ShklovskysreadingofPudovkinsepic

film,essentially,construesthemovingimagetobeatext,reducingvisionandvisualimagesto

language.InthissenseItakethewritingsofRussianFormalistsonfilm,particularlyShklovskys

inthisinstance,torepresentakindrebuspuzzleoranintersectionofvisualrepresentationand

language,wherewecanscrutinizehowmovingimageswereinterpretedthroughliterarymodels.

Shklovsky began to write about cinema at the time when Soviet films exhibited a

radicallyoriginalstyle,generallyknownasmontage(Bordwell,9).Montagewasusedtobuild

anarrative(byformulatinganartificialtimeandspaceorguidingtheviewersattentionfrom

onenarrativepointtoanother),tocontrolrhythm,tocreatemetaphors,andtomakerhetorical

points(Ibid).AndreBazin,usefullydefinesmontageasthecreationofasenseormeaningnot

objectively contained in the images themselves but derived from their juxtaposition (25).

VsevolodPudovkinwasamongthemainexponentsofmontage,alongwithSergeiEisenstein,

DzigaVertov,andLevKuleshov.ButwhileKuleshov,andhispupilPudovkinutilizedmontage

primarilyforrhythmicandnarrativeends,EisensteinandVertov,soughttogobeyondnarrative

editing to make metaphorical and rhetorical statements (Bordwell, 10).The four werealso

divided in their wider allegiances. While Kuleshov and Pudovkin stood,as David Bordwell

states,intheartisticallyadvancedwingoftheconservativefilmmakers,VertovandEisenstein

Mandui3

werealigned withLEF,thepoliticalfactionofartists whowereaestheticallyandpolitically

revolutionary. In addition to participating in the work of Russian Formalist on cinema and

literature,VictorShklovskyalsobelongedtotheavantgardeLEFgroup(13).

TheliterarymindedFormalistsstudiedtheorganizingprinciplesofthethrivingcinematic

mediumasanextensionoftheirattemptstodeterminethestructuresthatconstituteworksof

proseandverse.Oneoftheprincipalquestionstheywantedtoanswerwiththeirliterarytheories

askedwhetheranarrativecouldproceedonthebasisofstylisticvariationinsteadofstoryactions

(Stam,72).Inhisshortbook LiteratureandCinema,(1923),Shklovskyclaimedthatafilm

withoutplot,whichwouldsolelyrelyforitseffectonformaldevices,wasimpossiblesinceplot

organizesactionsintocohesiveform(32).WritingintheFormalistanthologyPoeticsofCinema,

JuriTynianovclaimedthemostadvancedworksofcinemadispensedwiththestory.Thisstory

lesspoeticcinemaunfoldsonthebasisofplotpatterningandformalvariations(Ibid).

ShklovskyscontributiontotheFormalistanthologyhasbecomeoneofthefundamental

textsdefiningpoeticcinema.TitledPoetryandProseinCinema,thisbriefarticledefineshow

cinemaisclosertoversethanitistoprose,principallybecausefilmallowsforpoeticformal

resolutions.ShklovskyidentifiespoeticdevicesinPudovkins Mother,highlightingthefilms

ending as an example of the displacement of the everyday by purely formal elements. He

characterizes the films transition fromprosetopurely formal poetry as a uniquecentaur.

Shklovskygoesontosuggestthattheemphasisonformaloversemanticfeatures,whereformal

features displace semantic elements (to) resolve the composition, could be the basis for

distinctionsbetweenfilmgenres(1988,178).Butthenotionofthecentaur,ratherthesuggesting

Mandui4

twoseparatecategories,impliesakindoffusionoftwoelementsintoone;themaletorsoandthe

horselegsfunctionasone.PudovkinscombinationofdifferenteditingstylesinTheEndofSt.

Petersburgsuggestsasimilarkindoffusion.IntheNovyiLefarticle,Shklovskyisrespondingto

amoreprevalentfusionofstylesincontrasttoPudovkinsearlierfilm.ThoughShklovskyhad

previouslyassertedtheprimacyofthescriptandorganizationoffilmmaterials(Taylor,184),he

considershowthefilmsincongruousplotstructurefunctionsinrelationtoformalandstylistic

variations,orhowmistakesinthescriptledtocinematicinnovations.

ShklovskypointofdeparturefordiscussingPudovkinsfilm,suggestswhatdominant

conceptorganizeshisworkoncinema,namelytheorganizationoffilmmaterialthroughplot.He

faultsPudovkinfornotcontrastingthestoryofaworkersfamilywithadifferentplotratherthan

placing it against a background of historical montage. He claims the narrative balance was

sacrificedduringrevisionsoftheoriginalscript.Theinitialscriptapparentlyofferedasubplot

dealing with a White Guard sympathizer to counterbalance the main plot of socialist moral

enlightenment.Thiscompositionalchoiceordeletionapparentlyproducedanartisticallypaler

andlesspoliticallysignificantfilmthenthescriptfirstsuggested.Pudovkinwasthenforcedto

mask the absence of a whole section of the (films) construction through pathos inducing

montage(182).

Pudovkinsearlyconceptionsofthefilm,faroutstripsthescopeoftheversionShklovsky

is holding the director accountable for. Over the course of editing the script, Pudovkin

surrenderedtheepicdimensionsofthefirstdrafts,infavorofthepoliticaleducationofpeasants

andworkers.Thedirectororiginallyimaginedanexpansivestoryspreadingoverthreeepochs

Mandui5

andsocialchangesinRussia,underthecomprehensivetitle PetersburgPetrogradLeningrad.

Thelatternarrowerversionwasdesignedtopresentamorelimitedviewthroughtheimmediate

experience of individual characters caughtup in the events between World War I and the

OctoberRevolution.

ThenarrativeabsenceShklovskyidentifiesechoeshisclaimsforcounteractionforastory

tobeunderstoodassomethingtrulycomplete(1990,52).WhereastheWhiteGuardsubplot

would have been incongruous tothe main action, it would have counterbalanced the action

centeredonthemaincharacters:theLad,theWife,theCommunistWorker,andthefactory

ownerLebedev.Inthisdiscussionofnarrativeabsencewerecognizeoneofthebasicprinciples

oftheFormalistapproachtocinema,whichaskedifthestory,understoodasalinkedseriesof

actions,constitutedthecoreofnarrativestructure,orifnarrativeproceededonthebasisof

stylistic variations (Stam, 72). As its primary position in the article suggests, Shklovskys

discussionofthefilmsnarrativedeficienciesisgroundedinhisviewoftheprimacyofthescript

andofplotintheorganizationoffilmmaterial,theplotconstitutedbydevice.Inthissense,as

longashediscussesthewrittentextofthescript,Shklovskysargumentremainsontheliterary

level. Atthis pointhe solely focuses onthe narrative structure ofthe film, TheEnd ofSt.

Petersburgismoreatextratherthanaworkofvisualrepresentation.

Shklovskyemphasizesthistransformationofsuchmaterialbyformaldevices,whenhe

assertsthattheabsenceofplotstructurein TheEndofSt.Petersburg canbeconsidereda

cinematicinvention,whichtakesupthechallengesofpoeticcinemaandtheproblemsofshot

compositionandframing.ButwhenShklovskyswitcheshisemphasisfromscriptandplottothe

Mandui6

visualrepresentationandthemovingimage,heusesliteraryanalogiestodiscussPudovkins

style of editing. Moving from the issue of plot construction to problems of poetic cinema,

Shklovsky establishes his paragon in the context of poetry. He cites the substitution of

compositional surrogates for semantic elements, such as the appearance/disappearance of

caesura, which can, in the final line of a lyric poem, replace a semantic resolution (72).

Shklovsky offers a more extensive explanation of the this device in his contribution to the

Formalist anthology Poetics of Cinema, by referencing the work of the nineteenth century

RussianpoetAfansiFet(182092).Hedescribeshowafterfourstanzasinaparticularmeterwith

acaesura,anunnamedpoemisnotresolvedbyitsplot,butbythefactthefifthstanza,while

beinginthesamemeter,hasnocaesura,whichcreatesasenseofclosure(1988,177).

WiththismodelwithShklovskyconsidersformaltransformationsofsemanticmoments

intopoeticmontagesequencesinPudovkinsfilm.Heisparticularlyfascinatedintheelliptical

montagesequencethatshowsseveralfactoryimagesofbillowingsmoke,turningwheels,and

driving piston rods in the Peterburg sequence. Shklovsky asserts that a factory is thus

transformedintoamontagesequence(1988,180).ThoughShklovskylargelyemphasizedthe

importanceofplotanditsorganizationbystoryactions,hisenthusiasmforPudovkinsuseof

montageTheEndofSt.Petersburg,correlatestohisacceptanceofformalcinematicresolutions

asequalsofstoryactionsintermsoffilmresolution.Additionally,wealsohavetokeepinmind

thatPudovkincontrastedthequickeditingofthefactorymontagesequenceandtherelativestasis

oftheprecedingsceneintheapartment,inordertoachievearhythmicaldisjunctionandthekind

incongruityShklovskyseeksinnarrative.

Mandui7

Writing shortly before the completion of the film, Pudovkin described the montage

sequenceShklovskypraiseintheNovyiLefarticle asthecinematicdevelopment oftheme.

Whileheconsideredtherangeofstylisticpossibilitiesincinema,Pudovkinalsosuggeststhe

kindofincongruityheseekstocompose.Heasserts,Ifeverythingisfilmedasbeautiful,i.e.

basedonlyonexternalform,this,inmyview,isverybadbecauseinthefinalanalysistheviewer

willreceiveonlyonekindofexcitementfromandthatisaestheticenjoyment(Petersburg,

127).HethengoesontocredithiscameramanGolovniaforselectingthedistortinglensesand

oblique angle chosen for scenes in which Pudovkin wanted to achieve dynamic saturation.

Throughtheseassertions,PudovkinrevealshisaffinityforstylisticexperimentationasTheEnd

ofSt.Petersburgsuggestsinabruptswitchesbetweencontinuityeditingandmontagepassages.

WhileShklovskystranspositionofFormalistliterarytheoryintohisworkoncinema

reflectstheinterchangebetweenartistsandwritersinmultipleaestheticmediumsandinmultiple

debates,theworkofVsevolodPudovkin,particularly TheEndofSt.Petersburg,suggestsa

differentkindofexchangeofstylesandcinematicstrategies,occurringwithintheboundsofthe

filmmedium.Pudovkinswasduallyinterestedinexperimentingwiththeuseofmontageto

createmetaphorsandmakerhetoricalpoints,aswellastheuseofmontagetoenergizefilm

narratives through editing (Kepley, 29). Studying in Lev Kuleshov celebrated workshop,

PudovkinwasimpressedbyhowAmericanmoviesgeneratedamoreimmediateandanimated

spectator,whichtheKuleshovgroupattributedtoquicker,moresophisticatededitingtechniques

(Ibid).PudovkinscrossfertilizationofeditingstylesinTheEndofSt.Petersburgrepresentsthe

Mandui8

filmmakers assimilation of distinct influences, which are however contained within the

cinematicmedium.

Pudovkins conception of representing reality throughdetails takes after the work of

D.W. Griffith. He credits Griffith with incredible ability to select from a mass of real raw

materialthemostrevealingdetailsandachieveanoverpoweringimpact.ForPudovkinevery

phenomenon has to be dissected into its parts (Ibid). The technique of observation is thus

combinedwiththecreativeactivityofchoosingthecharacteristicselements(Ibid).Pudovkin

thusdeclaresthenecessityofcastingasideintermediateandinsignificantelementsofinevitable

reality,sothatparticularhighlightscanbeusedtocreategreatcinematicimages.

ShklovskysconsiderationofPudovkinsworkwiththecleansedshotimpliesaclose

associationtotheliterarycriticswellknowncontentionthattheessenceofworkofart(lies)in

the renewing perceptionsaboutrealitywhichdailylifetendedto automatize(Eagle,4).He

asserts,Pudovkinsattempttoworkwiththecleansedshothasproducedintheshotofdailylife

anextraordinaryuseofrawmaterial(Shklovsky1988,182).InasmuchasShklovskyattributes

thesemblanceofrealitytotherepresentationofsomethingoutofitsnormalcontext,hethen

identifies in Pudovkins the strategy 'defamiliarization.' This conjecture is suggested by

Shklovskyfascinationwithimageofateacup.Whenthepolicearrivetoarrestthehusbandthey

realizefromthesteamingteacupthatthehusbandhadjuststeppedoutandwilllikelyreturn

soon.Pudovkininsertscloseupsoftheteacupwithinaseriesofprofiledepictionsofpolicemen

andtheWifestrikingoffscreenglance.ThesteamingcupofteaunderShklovskyscrutinyis

insertedtoheightentheanticipationasitimpliesthehusbandsimpendingreturnandtheensuing

Mandui9

actionseries.ThusforShklovsky,itwouldappearthisdetailrepresentsameansforintensifying

thesensationofreality.

Shklovskys theory of ostranenie, translated as the defamiliarization or making

strange,firstpostulatedinhisessayArtasDevice(1919),ledtheRussianFormaliststomake

theirprincipalfocusofstudiesthosedevicesthatstructurerawmaterialsinworksofartandare

usedtorenewtheperceptionreality.ByadoptingShklovskysview,theFormalists cameto

considerhowdevicesgenerallyfunctionedinart.Inthissense,Shklovskysworkoncinemawas

dedicatedtotheanalysisofhowartformtransformsmaterialstakenfromlifeintoasignifying

systemcapableofgeneratingnewinsightsabouthumanexperience(Eagle,5).

ConceptualparallelsbetweenShklovskysstrategyofdefamiliarizationorthemaking

strangeofrealityasaremedyfortheautomatizationofourresponses,andPudovkinsown

theoriesofhowrealityistoberepresentedspecificallysuggestthekindofsuturingofimage

and writing that constitutes films, particularly in the silent era. The directors detailed

considerationsofhowcertainsituationssuchascaraccidentsshouldbecinematicallydepicted

subordinates language to the discussion of visual representation. While Shklovskys

transposition of Formalist literary theory into his work on cinema reflects the interchange

betweenartistsandwritersinmultipleaestheticmediumsandinmultipledebates,theworkof

Vsevolod Pudovkin, particularly The End of St. Petersburg, suggests a different kind of

exchangeofstylesandcinematicstrategies,occurringwithintheboundsofthefilmmedium.

WhilePudovkinwasorientedtowardthevisualrepresentationofreality,Shklovskysreadingof

TheEndofSt.Petersburgisheavilyreliantuponliterarytheory.LikeShklovsky,JuriTynianov

Mandui10

alsousedverseformsashisprincipalparallels,arguingthatthejumpingnatureofcinema,the

roleofshotunityinit,thesemantictransformationofeverydayobjects(wordsinverse,thingsin

cinema) allofthesebringcinema andversetogether(Eagle,94).Butwhereas Tynianov

called for storyless poetic films, Shklovsky accepted formal resolutions (oppositions,

repetitions, and parallelism) as well as story actions, (transactions, developments, and

resolutions)asequaldevicesusedfortheattainmentofclosure.However,inhisanalysisofThe

EndofSt.Petersburg,hereducesvisualrepresentationtoliterarydevicesshowinghowRussian

Formaliststendedtoreadfilmsastextsofpoeticverse.

You might also like

- The Men with the Movie Camera: The Poetics of Visual Style in Soviet Avant-Garde Cinema of the 1920sFrom EverandThe Men with the Movie Camera: The Poetics of Visual Style in Soviet Avant-Garde Cinema of the 1920sNo ratings yet

- Soviet Montage TheoryDocument13 pagesSoviet Montage TheoryAleksandar Đaković100% (1)

- Soviet MontageDocument13 pagesSoviet MontageAbhishek ParasuramNo ratings yet

- Faucet TeDocument7 pagesFaucet TeEduardo HernandezNo ratings yet

- Kieslowski - FilmsDocument12 pagesKieslowski - FilmsMatijaNovakovic100% (1)

- Patterson, David W. - BilješkeDocument6 pagesPatterson, David W. - BilješkeBojan Nečas-HrasteNo ratings yet

- Michael Thomas Hudgens The ShakespeDocument4 pagesMichael Thomas Hudgens The ShakespeMihaela IstratiNo ratings yet

- Music and Mirrors in Hitchcocks VertigoDocument10 pagesMusic and Mirrors in Hitchcocks VertigoSTELIOS SIDISNo ratings yet

- 15776-Tekst Artykułu-31493-1-10-20210331Document21 pages15776-Tekst Artykułu-31493-1-10-20210331Deenan KathiravanNo ratings yet

- On DovzhenkoDocument2 pagesOn DovzhenkoSushil JadhavNo ratings yet

- RMA Thesis PDFDocument120 pagesRMA Thesis PDFtcmdefNo ratings yet

- O Muzyke D Shostakovicha V Naraschivanii Smysla Eticheskoy Kontseptsii Filmov G Kozintseva Gamlet I Korol LirDocument50 pagesO Muzyke D Shostakovicha V Naraschivanii Smysla Eticheskoy Kontseptsii Filmov G Kozintseva Gamlet I Korol LirMihaela IstratiNo ratings yet

- Soviet Montage CinemaDocument40 pagesSoviet Montage CinemaScott Weiss100% (1)

- Russian Film Director Screenwriter Actor Montage Sergei EisensteinDocument8 pagesRussian Film Director Screenwriter Actor Montage Sergei EisensteinPriyam ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Andrei Rublev Film-Creative Vision PDFDocument9 pagesAndrei Rublev Film-Creative Vision PDFRyan HayesNo ratings yet

- (24513474 - Open Cultural Studies) "Exquisite Cadaver" According To Stanisław Lem and Andrzej WajdaDocument11 pages(24513474 - Open Cultural Studies) "Exquisite Cadaver" According To Stanisław Lem and Andrzej WajdaFúserSatrústeguiNo ratings yet

- Ozep 121 Mackenzie SovietDocument6 pagesOzep 121 Mackenzie SovietmtstNo ratings yet

- The Film Factory 1Document18 pagesThe Film Factory 1Laura GrigoriuNo ratings yet

- Russian Film Studies 20105 IV 7 OffprintDocument13 pagesRussian Film Studies 20105 IV 7 OffprintJeremy HicksNo ratings yet

- Fedorov, Alexander. Cinema in The Mirror of The Soviet and Russian Film Criticism. Moscow: ICO "Information For All", 2019. 214 P.Document214 pagesFedorov, Alexander. Cinema in The Mirror of The Soviet and Russian Film Criticism. Moscow: ICO "Information For All", 2019. 214 P.Alexander FedorovNo ratings yet

- MontageDocument14 pagesMontageBabbo di minchiaNo ratings yet

- On The Terminal On CinemaDocument7 pagesOn The Terminal On CinemawernickemicaNo ratings yet

- Dovzhenko and MontageDocument16 pagesDovzhenko and MontageyuNo ratings yet

- Daniel Fairfax, Marxism and CinemaDocument28 pagesDaniel Fairfax, Marxism and CinemaakansrlNo ratings yet

- Tarkovsky and BrevityDocument16 pagesTarkovsky and BrevityEun Suh Rhee100% (1)

- Montage and Its Effects On The Audience in Russian CinemaDocument14 pagesMontage and Its Effects On The Audience in Russian CinemaMathilde DmNo ratings yet

- Collage ReportDocument1 pageCollage ReportAdreija MandalNo ratings yet

- Early Soviet CinemaDocument4 pagesEarly Soviet CinematatanicoNo ratings yet

- Kieslowski Art of FilmDocument13 pagesKieslowski Art of FilmvarunNo ratings yet

- Introduction Deleuze and Tarkovsky PDFDocument8 pagesIntroduction Deleuze and Tarkovsky PDFJosé Luis Gómez Ramírez100% (2)

- Cinemas of Late and Post - Socialism: China and RussiaDocument4 pagesCinemas of Late and Post - Socialism: China and RussiaGiada Di TrincaNo ratings yet

- Sven LuttickenDocument5 pagesSven Lutticken13lauto1No ratings yet

- And Up She Went - The Moral Vertical in WingsDocument11 pagesAnd Up She Went - The Moral Vertical in WingsOlga VereliNo ratings yet

- Screenplays As LiteratureDocument19 pagesScreenplays As LiteratureLaura Botero LópezNo ratings yet

- Alexander Kluge - Senses of CinemaDocument15 pagesAlexander Kluge - Senses of CinemaGawan FagardNo ratings yet

- Zviagintsev February 2015Document15 pagesZviagintsev February 2015nancy condeeNo ratings yet

- Dogtooth ReviewDocument4 pagesDogtooth ReviewMax BastowNo ratings yet

- Aisyah - Academic Essay - Soviet MontageDocument6 pagesAisyah - Academic Essay - Soviet MontageAisyah Rasyidah ReduanNo ratings yet

- China Perspectives: Claire Shen Hsiu-Chen, L'Encre EtDocument4 pagesChina Perspectives: Claire Shen Hsiu-Chen, L'Encre EtEsdras OliveiraNo ratings yet

- A Cinematic and Physiological PuzzleDocument31 pagesA Cinematic and Physiological PuzzleCarlos De Landa AcostaNo ratings yet

- Triumph of The Battleship: Cinematographic and Edited IdeologyDocument9 pagesTriumph of The Battleship: Cinematographic and Edited IdeologyJody MunozNo ratings yet

- Performing The Real and Its Lack: The Dialectical Performances of Slavoj Žižek in The Pervert's Guide To Cinema and The Pervert's Guide To IdeologyDocument18 pagesPerforming The Real and Its Lack: The Dialectical Performances of Slavoj Žižek in The Pervert's Guide To Cinema and The Pervert's Guide To IdeologyLuka LipertNo ratings yet

- EisensteinDocument41 pagesEisensteinmiroslavNo ratings yet

- Japanese Noh and The Stanislavski Method MeetDocument22 pagesJapanese Noh and The Stanislavski Method MeetMaria MalagònNo ratings yet

- MontageDocument5 pagesMontageCharles BrittoNo ratings yet

- A Little Light Teasing Some Special Affects in Avant Garde CinemaDocument15 pagesA Little Light Teasing Some Special Affects in Avant Garde CinemaRodrigo LopezNo ratings yet

- 10 Great Polish FilmsDocument14 pages10 Great Polish FilmsJavier DaríoNo ratings yet

- Queer Representations in Chinese Language Film and The Cultural LandscapeDocument43 pagesQueer Representations in Chinese Language Film and The Cultural LandscapetobyhuterNo ratings yet

- Enthusiasm-Eye VertovDocument13 pagesEnthusiasm-Eye VertovDwayne DixonNo ratings yet

- TRET'IAKOV - The Theatre of AttractionsDocument8 pagesTRET'IAKOV - The Theatre of AttractionsjohnnyNo ratings yet

- KieslowskiDocument16 pagesKieslowskimiroslavNo ratings yet

- Hamish Ford The Return of The 1960s Modernist CinemaDocument16 pagesHamish Ford The Return of The 1960s Modernist CinemaleretsantuNo ratings yet

- Yashiko Okada - Life in USSRDocument24 pagesYashiko Okada - Life in USSRpratik_boseNo ratings yet

- Kinowa Materialność Teorii DeleuzeDocument36 pagesKinowa Materialność Teorii DeleuzeSofa z IkeiNo ratings yet

- Interview With Alexander KlugeDocument9 pagesInterview With Alexander KlugeAidan CelesteNo ratings yet

- Blind ChanceDocument8 pagesBlind ChanceIulia OnofreiNo ratings yet

- Shklovski y BakhtinDocument28 pagesShklovski y BakhtinConstanza LeonNo ratings yet

- Love's Old Song Will Be New: Deleuze, Busby Berkeley and Becoming-MusicDocument18 pagesLove's Old Song Will Be New: Deleuze, Busby Berkeley and Becoming-MusicAli RahmjooNo ratings yet

- Research Methods in Visual Media - IordacheDocument18 pagesResearch Methods in Visual Media - IordacheFlorin AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Page 9Document1 pagePage 9Zdenko MandušićNo ratings yet

- Plan Questions To Uncover Misconceptions in The Asynchronous MaterialDocument3 pagesPlan Questions To Uncover Misconceptions in The Asynchronous MaterialZdenko MandušićNo ratings yet

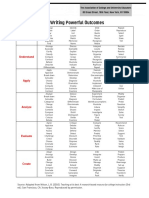

- Action Verbs For Writing Powerful Outcomes: RememberDocument1 pageAction Verbs For Writing Powerful Outcomes: RememberZdenko MandušićNo ratings yet

- Words by Wordy Woodwards NewDocument1 pageWords by Wordy Woodwards NewZdenko MandušićNo ratings yet

- Ministry of CultureDocument46 pagesMinistry of CultureZdenko MandušićNo ratings yet

- Establishing Powerful Learning OutcomesDocument2 pagesEstablishing Powerful Learning OutcomesZdenko MandušićNo ratings yet

- El Lissitsky - The Future of TDocument8 pagesEl Lissitsky - The Future of TvincentgangloffNo ratings yet

- Lining Up Page Numbers in The Table of ContentsDocument1 pageLining Up Page Numbers in The Table of ContentsZdenko MandušićNo ratings yet

- George E. Marcus, Fred R. Myers-The Traffic in Culture - Refiguring Art and Anthropology - University of California Press (1995) PDFDocument392 pagesGeorge E. Marcus, Fred R. Myers-The Traffic in Culture - Refiguring Art and Anthropology - University of California Press (1995) PDFjudassantos100% (1)

- Anna Akhmatova - PoemsDocument36 pagesAnna Akhmatova - PoemshomiziadoNo ratings yet

- Khhoxpohhka - Bejimkofi Otemectbehhofi Bohhbl 0 - : Bepjihh R. Pemwccepbi Cnhjioba, CetkhhaDocument4 pagesKhhoxpohhka - Bejimkofi Otemectbehhofi Bohhbl 0 - : Bepjihh R. Pemwccepbi Cnhjioba, CetkhhaZdenko MandušićNo ratings yet

- The Junctures of Children S Psychology PDFDocument81 pagesThe Junctures of Children S Psychology PDFZdenko MandušićNo ratings yet

- Concrete Analysis of Concrete Situations: Marxist Education According To Želimir Žilnik - Branislav DimitrijevićDocument4 pagesConcrete Analysis of Concrete Situations: Marxist Education According To Želimir Žilnik - Branislav DimitrijevićZdenko MandušićNo ratings yet

- Pilots Behaving Badly and The Visual Attraction of Their Planes: How Mikhail Kalatozov Returned To FilmmakingDocument9 pagesPilots Behaving Badly and The Visual Attraction of Their Planes: How Mikhail Kalatozov Returned To FilmmakingZdenko MandušićNo ratings yet

- Mandušić, Avant-Garde Stalinism Final ProjectDocument10 pagesMandušić, Avant-Garde Stalinism Final ProjectZdenko MandušićNo ratings yet

- Mandušić, Avant-Garde Stalinism Final ProjectDocument10 pagesMandušić, Avant-Garde Stalinism Final ProjectZdenko MandušićNo ratings yet

- 2637 2528 Quarta 6 Druk PDFDocument16 pages2637 2528 Quarta 6 Druk PDFKhawlaAzizNo ratings yet

- 1guide For The Student TrombonistDocument16 pages1guide For The Student TrombonistJesus Laserna Ruiz100% (3)

- Tepu-Mereme - Petroglyphs and Rock Paintings of VenezuelaDocument5 pagesTepu-Mereme - Petroglyphs and Rock Paintings of VenezuelaSounak SardarNo ratings yet

- Monnalisa: A Presentation On Kidswear By: Juhu Bhavsar Prachi Nupur ModiDocument27 pagesMonnalisa: A Presentation On Kidswear By: Juhu Bhavsar Prachi Nupur ModiAbhinav VermaNo ratings yet

- Puri Ravel and ProustDocument18 pagesPuri Ravel and ProustDana KiosaNo ratings yet

- AHW4 GrammarSpot U01Document32 pagesAHW4 GrammarSpot U01yairherrera100% (4)

- PWRHRH 1Document2 pagesPWRHRH 1api-203604001No ratings yet

- World Papercraft Buildings of The World Series India (Section 1)Document4 pagesWorld Papercraft Buildings of The World Series India (Section 1)GregNo ratings yet

- ParrDocument15 pagesParrPaul Vincent100% (1)

- Opening CreditsDocument2 pagesOpening Creditskbintu63No ratings yet

- Shugborough InscriptionDocument5 pagesShugborough InscriptionTayaChandranNo ratings yet

- Far Wes PDFDocument6 pagesFar Wes PDFdavid_gray11150% (6)

- Spanish Stu Textbook M1Document242 pagesSpanish Stu Textbook M1Cristina Vasiliu100% (3)

- Anton WebernDocument4 pagesAnton WebernFrancis AmoraNo ratings yet

- Whales ProjectDocument9 pagesWhales Projectapi-265936561No ratings yet

- Camille Pissaro FinalDocument18 pagesCamille Pissaro FinalSakshi JainNo ratings yet

- Texas Standard ProDocument1 pageTexas Standard ProJordi Sala DelgadoNo ratings yet

- LV Kuce I Sahranjivanje EngleskiDocument20 pagesLV Kuce I Sahranjivanje EngleskiNenad TrajkovicNo ratings yet

- CELTA Language Analysis Sample 3 Grammar Future Perfect PDFDocument2 pagesCELTA Language Analysis Sample 3 Grammar Future Perfect PDFRebecca Tavares Puetter33% (3)

- A Door Into HindiDocument8 pagesA Door Into HindiMuhammad Najib LubisNo ratings yet

- Anna Crocheted Doll PatternDocument6 pagesAnna Crocheted Doll PatternAnNo ratings yet

- Finn Juhl Catalog PDFDocument27 pagesFinn Juhl Catalog PDFMo NahNo ratings yet

- Monopods PDFDocument15 pagesMonopods PDFChonlatid Na PhatthalungNo ratings yet

- Lady Gaga - ApplauseDocument6 pagesLady Gaga - ApplauseRomanJuarezNo ratings yet

- HTTP Pre FarottiDocument1 pageHTTP Pre FarotticicciolaNo ratings yet

- Gamaba AwardeesDocument22 pagesGamaba AwardeesSienna Cleofas100% (1)

- Adv TEchniques Latin Rhythm Secition - John LopezDocument35 pagesAdv TEchniques Latin Rhythm Secition - John LopezRaga Bhava100% (1)

- Midsommer NIghts Dreame 1890 Variorum EditionDocument392 pagesMidsommer NIghts Dreame 1890 Variorum EditionTerryandAlan100% (1)

- Nazia Hassan Aap Jai Sa Koi Song Lyrics QurbaniDocument3 pagesNazia Hassan Aap Jai Sa Koi Song Lyrics QurbaniNarayanan MuthuswamyNo ratings yet

- La Voz Pasiva PDFDocument4 pagesLa Voz Pasiva PDFAdrianCasadoNo ratings yet