Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Salih Ozbaran - Ottoman Seapower and Levantine Diplomacy in The Age of Discoveryby Palmira Brummett

Uploaded by

mhmtfrtOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Salih Ozbaran - Ottoman Seapower and Levantine Diplomacy in The Age of Discoveryby Palmira Brummett

Uploaded by

mhmtfrtCopyright:

Available Formats

British Society for Middle Eastern Studies

Ottoman Seapower and Levantine Diplomacy in the Age of Discovery by Palmira Brummett

Review by: Salih Ozbaran

British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 23, No. 2 (Nov., 1996), pp. 208-209

Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/195538 .

Accessed: 28/06/2014 07:30

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Taylor & Francis, Ltd. and British Society for Middle Eastern Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.49 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:30:16 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEWS: GENERAL

Shi'i imams, was to prove an obstacle to the spreadingof his influence in the Shi'i world

after his death. Another obstacle was his emphasis on the relationship between the

master and the disciple, which inevitably weakened his influence once he had died.

Yet his writings on the key concepts of Sufism are remarkablefor their perspicacity.

One of the most distinctive aspects of his thoughtis the difficulty involved in following

the mystical path. Mystical experience is easily capable of unbalancingthe practitioner,

and there are many forms of diversion from the path. Simnani was keenly aware of the

dangers of mysticism, and he insisted throughouton the importanceof obeying the law

and carryingout faithfully the rituals of religion. There is no scope for humanbeings to

become united with God since a contingent being cannot be united with a necessary

being. On the contrary,the most that human beings can do is to mirror God through

personalperfection,which is only attainableat the end of the mystical path. The ultimate

mystical truthsare entirely in accordancewith Sunni normativism,since human beings

as the most perfect of God's creations have to act as his representativeson earth, as

custodians of the sacred trust. These views came to have great influence on the

Naqshbandiyyasect, especially through their impact on Ahmad-i Sirhindi.

In his scholarly and well-written book Elias provides a lot of detail on topics such as

the relationship of God and the world, the spiritual body and the mirror of God, the

nature of subtle substances and the role of emanation in Sufism. There is an extended

and useful discussion of how Simnani interpretsthe key Sufi concepts and religious

ideas. He also provides an account of his works, and of works on him, together with a

discussion of the precise cultural and political context within which he operated. His

conclusion, that the importance of Simnani for his successors lies in his ability to

reconcile the social and spiritualdimensions of humanexperience within a theory of the

natureof existence, is plausible. Such a theory sees the spiritualand the materialworlds

as linked, but neither as reducible to the other. It is incumbentupon the Sufi, then, to

concentrateon the mystical path, but this should not involve neglect of the obligations

which attend life in the world of generation and corruption.Similarly, although one

should carry out one's duties as a member of a community, as a human being, this

should not be at the expense of the capacity to seek deeper understandingof the nature

of reality. It is not surprisingthat this powerful idea came to have many adherentsin the

Islamic world.

LIVERPOOLJOHN MOORES UNIVERSITY

OLIVER LEAMAN

OTTOMAN SEAPOWERAND LEVANTINE DIPLOMACY IN THE AGE OF DISBRUMMETT.

COVERY. By PALMIRA

(SUNY Series in the Social and Economic History

of the Middle East.) New York, State University of New York Press, 1994. xvi, 285 pp.

2 maps, 7 plates. $19.95.

The first thing which strikes the reader about this book is the author's reminderof the

necessity for cooperation and universal understandingcaused by the expansion of

Western historiographyinto Ottoman history, and the failure of both scholarly and

popularwriting in the 'dominant'world to appreciatethe natureof Ottomanexpansion,

seapower, and integration into the Euro-Asian commercial patterns in 'the Age of

Discovery'.

The aim of this study is to tell the story not from the 'overwhelmingly structured'

point of view prompted by the term 'the Age of Discovery'. It is rather to have 'a

208

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.49 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:30:16 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REVIEWS: GENERAL

differentworld map, centringnot on Lisbon, Antwerp,Amsterdam,Paris or London, but

on Istanbul, Cairo and Tabriz' (p. 2). The objectives of Ottoman expansion were the

same as those of the Europeans: wealth, power, glory, religious legitimation-the

rhetoricof holy war cannot suffice to articulatethe image of the Ottomanempire in the

sixteenth century.

Professor Brummett has every reason to object that Western historiography has

frequentlykept the Ottomanempire within the category of 'the other', with little attempt

made to understandthe balance of power in the Euro-Asiam sphere. Her approachis

welcome, following in the wake of historians such as Inalcik, Orhonlu, Faroqhi,

Wallerstein,Godino, Hess and Wesseling, who have includedthe Ottomanempire within

the competition for world economic power and have avoided the stereotyping which

contrastsa 'static Orient' with a 'dynamic Occident'. Her book addressesthe following

themes: reassessment of the impact of Ottoman naval development on the world

economy; revision of analyses of Ottomaneconomic policy; examinationof the details

of participationby the Ottomanstate, its merchants,and askeri (military-administrative)

class in trade. She raises-rather than answers-crucial questions, such as: how was the

state concerned with marketsand could it increase profits?What were supply, demand,

prices, raw materials,capital, products,technology, organization,mercantileinstitutions,

profit?What was the level of consumption,of agriculturalsurpluses, and the extent of

commandeering?What was the relationshipbetween agricultureand commercialcapital?

Who exploited surpluses and how? What was the extent of pasha, notable family, and

state agents' involvement as merchants(pp. 18-19)?

How far has the authorbeen able to advance understandingof these topics? In this

reviewer's opinion, it is very difficult to give sensible answers to such questions without

exploiting the relevant raw material. It is a pity that she has not gone through the

Ottoman archives in Istanbul, in particularfor cadastral surveys and account books,

budgets and their associated records, ruus appointmentregisters, and the muhimme

copies of orders and firmans issued by the imperial council concerning the southern

provinces of the empire. However, it is perhapsunfair to criticize the authortoo much

in this respect, for her work deals mainly with the first two decades of the sixteenth

century, for which Ottoman archival records are relatively sparse. She does seem to

have used chronicles,but these do not include the kind of data most useful for economic

and commercialpurposes-in this case one needs statisticaldata to comment on longue

duree activities. She also makes extensive (though bordering on excessive) use of

Marino Sanuto's I Diarii. In her frequentreferencesto the rest of the sixteenth century,

Brummett seeks to explain commercial life in its wider dimensions. In this context,

she might usefully have used work incorporating new Ottoman archival data, for

instance Cengiz Orhonlu on Ottoman expansion in the southern seas, Idris Bostan on

Ottomannaval organization,V. J. Parry on Ottoman warfare, and Suraiya Faroqhi on

the hajj.

Brummett successfully challenges 'the notion that the sixteenth-centuryOttoman

empire was merely a reactive economic entity, driven by the impulse to territorial

conquest' (p. 175); her work is strong on comparativeanalysis of Ottomandiplomatic,

political and commercial relations with their Safavid, Mamluk and European (mainly

Venetian and Portuguese)neighbours.Her work deserves an importantplace in historiographical consideration of the Ottoman empire, though it needs further detail to

illustrate and prove the claims which have been put forward throughoutthis book.

DOKUZ EYLUL UNIVERSITY, IZMIR

SALIH OZBARAN

209

This content downloaded from 91.220.202.49 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 07:30:16 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Haj Rifa'at 'Ali. Historiography in West Asian and North African Studies Since Sa'Id's Oriental Ism (2000)Document10 pagesHaj Rifa'at 'Ali. Historiography in West Asian and North African Studies Since Sa'Id's Oriental Ism (2000)kaygusuzbanuNo ratings yet

- İdris Bostan, Ottoman Empire Congo The Crisis of 1893-1895Document18 pagesİdris Bostan, Ottoman Empire Congo The Crisis of 1893-1895saitmehmettNo ratings yet

- Ibrahim MuteferrikaDocument4 pagesIbrahim MuteferrikaJulioAranedaNo ratings yet

- Images of Piracy in Ottoman Literature, 1550-1750Document12 pagesImages of Piracy in Ottoman Literature, 1550-1750Anonymous yAH8LaVDUCNo ratings yet

- SABEV, O. The Legend of Köse Mihal Turcica 34 (2002) 241-252.Document13 pagesSABEV, O. The Legend of Köse Mihal Turcica 34 (2002) 241-252.Grigor Boykov100% (1)

- Seljuk Caravenserais in The Vicinity of DenziliDocument121 pagesSeljuk Caravenserais in The Vicinity of DenziliNur AdilaNo ratings yet

- II. Abdülhamid Modernleşme Sürecinde İstanbul PDFDocument31 pagesII. Abdülhamid Modernleşme Sürecinde İstanbul PDFNilgün Özçelik100% (1)

- Sevket - Pamuk - Prices in The Ottoman Empire - 1469-1914Document18 pagesSevket - Pamuk - Prices in The Ottoman Empire - 1469-1914Hristiyan AtanasovNo ratings yet

- Books: Publications (Suraiya Faroqhi)Document16 pagesBooks: Publications (Suraiya Faroqhi)Anonymous Psi9GaNo ratings yet

- Yuzyil Istanbul Ermeni Dini Mimarisi PDFDocument14 pagesYuzyil Istanbul Ermeni Dini Mimarisi PDFarinda21No ratings yet

- Early Medieval Figure Sculpture from Northeast TurkeyDocument82 pagesEarly Medieval Figure Sculpture from Northeast TurkeyOnur GüvenNo ratings yet

- Ahmedis History of The Ottoman DynastyDocument8 pagesAhmedis History of The Ottoman DynastySaid GülNo ratings yet

- Studies in Ottoman History in Honour of Professor V.I. MenageDocument5 pagesStudies in Ottoman History in Honour of Professor V.I. MenageHristijan CvetkovskiNo ratings yet

- Aching IDocument132 pagesAching IAnonymous 7isTmailHuse100% (1)

- Ottoman BulgariaDocument17 pagesOttoman BulgariabbbNo ratings yet

- Midhat Pasha's Reforms in the Danube Province, 1864-1868Document139 pagesMidhat Pasha's Reforms in the Danube Province, 1864-1868Ferhat AkyüzNo ratings yet

- Günhan Börekçi TezDocument303 pagesGünhan Börekçi TezÖzge YıldızNo ratings yet

- The Crimean Tatars PDFDocument137 pagesThe Crimean Tatars PDFbosLooKiNo ratings yet

- Kanun and Shariah-Halil İnalcık PDFDocument10 pagesKanun and Shariah-Halil İnalcık PDFBuğraCanBayçifçi100% (1)

- Suleyman The Second and His TimeDocument427 pagesSuleyman The Second and His TimeabdalmalikNo ratings yet

- War and The Future: Italy, France and Britain at War by Wells, H. G. (Herbert George), 1866-1946Document91 pagesWar and The Future: Italy, France and Britain at War by Wells, H. G. (Herbert George), 1866-1946Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Inalcik 2007 The Ottoman Cift Hane SystemDocument12 pagesInalcik 2007 The Ottoman Cift Hane Systemashakow8849No ratings yet

- Avâriz Vergi Sistemi Içerisinde IltizamDocument14 pagesAvâriz Vergi Sistemi Içerisinde IltizamyasarugurluNo ratings yet

- ANZAC Deserters - PHD ThesisDocument190 pagesANZAC Deserters - PHD ThesisTwelve1201_4657897330% (1)

- Oğuz Kağan Narratives and the Turfan Oğuz NāmeDocument42 pagesOğuz Kağan Narratives and the Turfan Oğuz NāmemariusNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic Relations Between Safavid Persia and The Republic of VeniceDocument33 pagesDiplomatic Relations Between Safavid Persia and The Republic of VeniceAbdul Maruf AziziNo ratings yet

- A. Engi̇n Beksaç-Ti̇murlu Sanati TDVDocument5 pagesA. Engi̇n Beksaç-Ti̇murlu Sanati TDVmelike ikeNo ratings yet

- Osmanlı Trakya FethiDocument126 pagesOsmanlı Trakya Fethihyd arnes100% (2)

- Abû'l-Farac Tarihi 1Document376 pagesAbû'l-Farac Tarihi 1Ahmet Çağrı ApaydınNo ratings yet

- Loyalty and Political Legitimacy in The Phanariots Historical Writing in The Eighteenth Century Content File PDFDocument27 pagesLoyalty and Political Legitimacy in The Phanariots Historical Writing in The Eighteenth Century Content File PDFYarden MariumaNo ratings yet

- Colin Heywood, Colin Imber (Eds) - Studies in Ottoman HistoryDocument417 pagesColin Heywood, Colin Imber (Eds) - Studies in Ottoman HistoryHristijan CvetkovskiNo ratings yet

- University of California Press Possessors and Possessed, Museums Archaeology and The Visualization of History in The Late Ottoman Empire (2003)Document283 pagesUniversity of California Press Possessors and Possessed, Museums Archaeology and The Visualization of History in The Late Ottoman Empire (2003)Moja Casa100% (1)

- Dervish and Sultan: An Analysis of the Ottoman Baba VilayetnameDocument10 pagesDervish and Sultan: An Analysis of the Ottoman Baba VilayetnameAnonymous Psi9GaNo ratings yet

- Feryal - tezCOMMUNAL RELATIONS IN ĐZMĐR/SMYRNADocument277 pagesFeryal - tezCOMMUNAL RELATIONS IN ĐZMĐR/SMYRNAYannisVarthisNo ratings yet

- Ahmed Cemal Paşa - Nevzat Artuç PDFDocument481 pagesAhmed Cemal Paşa - Nevzat Artuç PDFBilgihan ÇAKIRNo ratings yet

- Cemal Kafadar, A Rome of Ones OwnDocument19 pagesCemal Kafadar, A Rome of Ones OwnakansrlNo ratings yet

- The Ottoman Special Organization Teskilati MahsusaDocument19 pagesThe Ottoman Special Organization Teskilati MahsusaFauzan RasipNo ratings yet

- 09 AhmetDocument15 pages09 AhmetRuy Pardo DonatoNo ratings yet

- Tursun Beg, Historian of Mehmed the ConquerorDocument9 pagesTursun Beg, Historian of Mehmed the Conquerorabdullah4yalva4No ratings yet

- Grube, Ernest J. - Threasure Od Turkey-The Ottoman Empire (The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, V. 26, No. 5, January, 1968) .Document21 pagesGrube, Ernest J. - Threasure Od Turkey-The Ottoman Empire (The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, V. 26, No. 5, January, 1968) .BubišarbiNo ratings yet

- András Róna-Tas-An Old Turkic Name of KievDocument6 pagesAndrás Róna-Tas-An Old Turkic Name of KievMurat SaygılıNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Reform in Iraq Under Abdulhamid II, 1878-1908Document32 pagesThe Politics of Reform in Iraq Under Abdulhamid II, 1878-1908Fauzan RasipNo ratings yet

- ATTENTION/MEMBERS OF THE U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES/May 19, 1985)Document5 pagesATTENTION/MEMBERS OF THE U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES/May 19, 1985)haufcaNo ratings yet

- History of The Modern Middle East-Fall 15Document5 pagesHistory of The Modern Middle East-Fall 15Kathleen RoseNo ratings yet

- Suleiman the Magnificent's 1538 Moldavian Campaign AgendaDocument10 pagesSuleiman the Magnificent's 1538 Moldavian Campaign Agendabobongo9038No ratings yet

- Islam As Practiced by The KazaksDocument18 pagesIslam As Practiced by The KazaksScottie GreenNo ratings yet

- Implementation of 1858 Ottoman Land Code in Eastern AnatoliaDocument193 pagesImplementation of 1858 Ottoman Land Code in Eastern AnatoliageralddsackNo ratings yet

- (Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization) Madeline C. Zilfi - Women and Slavery in The Late Ottoman Empire - The Design of Difference-Cambridge University Press (2010)Document291 pages(Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization) Madeline C. Zilfi - Women and Slavery in The Late Ottoman Empire - The Design of Difference-Cambridge University Press (2010)Bianca Șendrea100% (1)

- The Life of Celal BayarDocument6 pagesThe Life of Celal BayarmeleknazNo ratings yet

- Eliot Grinnell Mears - Modern Turkey 1908-1923 PDFDocument817 pagesEliot Grinnell Mears - Modern Turkey 1908-1923 PDFBuğraCanBayçifçiNo ratings yet

- Recent Books: Qasida Poetry in Islamic Africa and Asia, Ed. by Stefan SperlDocument11 pagesRecent Books: Qasida Poetry in Islamic Africa and Asia, Ed. by Stefan SperlmohammedNo ratings yet

- Seapower Technology and Trade. Studies I PDFDocument5 pagesSeapower Technology and Trade. Studies I PDFTsiggos AlexandrosNo ratings yet

- 1447-1514 Iki Imparatorluk Arasinda TürkmenlerDocument708 pages1447-1514 Iki Imparatorluk Arasinda TürkmenlerՅուրի Ստոյանով.No ratings yet

- The Flowering of Seljuq ArtDocument19 pagesThe Flowering of Seljuq ArtnusretNo ratings yet

- Cavalry Experiences And Leaves From My Journal [Illustrated Edition]From EverandCavalry Experiences And Leaves From My Journal [Illustrated Edition]No ratings yet

- Bureaucratic Reform in the Ottoman Empire: The Sublime Porte, 1789-1922From EverandBureaucratic Reform in the Ottoman Empire: The Sublime Porte, 1789-1922No ratings yet

- Spiritual Subjects: Central Asian Pilgrims and the Ottoman Hajj at the End of EmpireFrom EverandSpiritual Subjects: Central Asian Pilgrims and the Ottoman Hajj at the End of EmpireRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Salih Özbaran - THE OTTOMANS AND TRADE OTTOMANS AND THE INDIA TRADE IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY - SOME NEW DATA AND PDFDocument8 pagesSalih Özbaran - THE OTTOMANS AND TRADE OTTOMANS AND THE INDIA TRADE IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY - SOME NEW DATA AND PDFmhmtfrtNo ratings yet

- Salih Özbaran - THE OTTOMANS AND TRADE OTTOMANS AND THE INDIA TRADE IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY - SOME NEW DATA AND PDFDocument8 pagesSalih Özbaran - THE OTTOMANS AND TRADE OTTOMANS AND THE INDIA TRADE IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY - SOME NEW DATA AND PDFmhmtfrtNo ratings yet

- Mehmet İpşirli - Ottoman UlemaDocument15 pagesMehmet İpşirli - Ottoman UlemamhmtfrtNo ratings yet

- How To Be A Programmer enDocument78 pagesHow To Be A Programmer enmhmtfrtNo ratings yet

- For Instructions On Assembling The ASIMO Papercraft Model.: Solid LineDocument3 pagesFor Instructions On Assembling The ASIMO Papercraft Model.: Solid Linetostes_brNo ratings yet

- Power One Model SLI-48-115 Data SheetDocument5 pagesPower One Model SLI-48-115 Data SheetshartsellNo ratings yet

- ConcreteDocument1 pageConcreteRyan_RajmoolieNo ratings yet

- Nexus FP PDFDocument48 pagesNexus FP PDFPeter MkamaNo ratings yet

- A HELI 0022 V1 01 Rev1Document5 pagesA HELI 0022 V1 01 Rev1CuongDolaNo ratings yet

- Electronics Engineering CDR SampleDocument7 pagesElectronics Engineering CDR SampleCDR Sample100% (1)

- Mind Your Manners ReadingDocument58 pagesMind Your Manners ReadingВероника БаскаковаNo ratings yet

- ViewPoint - Global Shopping Centre DevelopmentDocument9 pagesViewPoint - Global Shopping Centre DevelopmentAiohue FalconiNo ratings yet

- Spec 120knDocument2 pagesSpec 120knanindya19879479No ratings yet

- User's Manual: & Technical DocumentationDocument20 pagesUser's Manual: & Technical DocumentationPODOSALUD HUANCAYONo ratings yet

- A Complete List of Books On Mead MakingDocument3 pagesA Complete List of Books On Mead MakingVictor Sá100% (1)

- Cambodian School of Prosthetics and Orthotics: CSPO ManualDocument60 pagesCambodian School of Prosthetics and Orthotics: CSPO ManualBilalNo ratings yet

- 320Document139 pages320Ashish SharmaNo ratings yet

- STP Model Marketing StrategyDocument25 pagesSTP Model Marketing StrategyRishab ManochaNo ratings yet

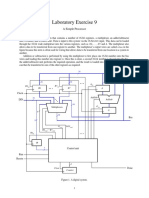

- Laboratory Exercise 9: A Simple ProcessorDocument8 pagesLaboratory Exercise 9: A Simple ProcessorhxchNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Respondents: Omar Villarba, Court of Appeals and People of The PhilippinesDocument19 pagesPetitioner Respondents: Omar Villarba, Court of Appeals and People of The PhilippinesJakie CruzNo ratings yet

- Telecommunication Group-8Document20 pagesTelecommunication Group-8Manjunath CNo ratings yet

- 008 Cat 6060 Attachment Functions BHDocument15 pages008 Cat 6060 Attachment Functions BHenrico100% (3)

- Formative Assesemnt Task-ENGLISHDocument18 pagesFormative Assesemnt Task-ENGLISHMonika Mehan100% (2)

- LAB REPORT 7 Aldol Reaction Synthesis 1 5 Diphenyl 1 4 Pentadien 3 OneDocument6 pagesLAB REPORT 7 Aldol Reaction Synthesis 1 5 Diphenyl 1 4 Pentadien 3 OneChimiste ChimisteNo ratings yet

- Preparing Your Tracks For Mixing - SoundBetterDocument5 pagesPreparing Your Tracks For Mixing - SoundBetterEmmanuel TuffetNo ratings yet

- Subwoofer Box 6.5 Inch Subwoofer Ported Box Pipe9Document2 pagesSubwoofer Box 6.5 Inch Subwoofer Ported Box Pipe9Arif Kurniawan HidayatNo ratings yet

- 1605Document8 pages1605Yuda AditamaNo ratings yet

- European Summary Report On CHP Support SchemesDocument33 pagesEuropean Summary Report On CHP Support SchemesioanitescumihaiNo ratings yet

- Ingersoll Rand Nirvana 7.5-40hp 1brochureDocument16 pagesIngersoll Rand Nirvana 7.5-40hp 1brochureJNo ratings yet

- Strategies in Teaching Social Studies Inductive and Deductive Andragogy vs. PedagogyDocument31 pagesStrategies in Teaching Social Studies Inductive and Deductive Andragogy vs. PedagogyArvie VillegasNo ratings yet

- The Role of NNN in Zeolite Acidity and ActivityDocument25 pagesThe Role of NNN in Zeolite Acidity and ActivityRaj MehtaNo ratings yet

- Antacid Booklet Final Sept 2015Document49 pagesAntacid Booklet Final Sept 2015MarianelaMolocheNo ratings yet

- AirOS 3.4 - Ubiquiti Wiki#BasicWirelessSettings#BasicWirelessSettingsDocument24 pagesAirOS 3.4 - Ubiquiti Wiki#BasicWirelessSettings#BasicWirelessSettingsAusNo ratings yet

- Python Programming For Beginners 2 Books in 1 B0B7QPFY8KDocument243 pagesPython Programming For Beginners 2 Books in 1 B0B7QPFY8KVaradaraju ThirunavukkarasanNo ratings yet

- Thomas McPherson Brown MD Treatment of Rheumatoid DiseaseDocument29 pagesThomas McPherson Brown MD Treatment of Rheumatoid DiseaseLidia Lidia100% (1)

![Cavalry Experiences And Leaves From My Journal [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/259895835/149x198/d6694d2e61/1617227775?v=1)