Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Morgan v. Greenbrier Co WV, 4th Cir. (2003)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Morgan v. Greenbrier Co WV, 4th Cir. (2003)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

UNPUBLISHED

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

VICTOR MORGAN and KIMBERLY

MORGAN, parents of and as next

friends of BRADLEY MORGAN, a

minor,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

GREENBRIER COUNTY WEST VIRGINIA

BOARD OF EDUCATION and STEPHEN

BALDWIN, as Superintendent of

Schools for Greenbrier County,

Defendants-Appellees.

No. 02-1687

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of West Virginia, at Beckley.

David A. Faber, Chief District Judge.

(CA-00-1211-5)

Argued: September 24, 2003

Decided: December 29, 2003

Before NIEMEYER, LUTTIG, and WILLIAMS, Circuit Judges.

Affirmed by unpublished per curiam opinion. Judge Williams wrote

a separate opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part.

COUNSEL

ARGUED: Silas Mason Preston, PRESTON & WEESE, L.C.,

Lewisburg, West Virginia, for Appellants. Jan L. Fox, STEPTOE &

JOHNSON, P.L.L.C., Charleston, West Virginia, for Appellees.

MORGAN v. GREENBRIER COUNTY WEST VIRGINIA

Unpublished opinions are not binding precedent in this circuit. See

Local Rule 36(c).

OPINION

PER CURIAM:

Victor and Kimberly Morgan, on behalf of their minor child Bradley, who is dyslexic, commenced this action to review the decision of

a West Virginia hearing officer rejecting in part their complaint about

the Greenbrier County (West Virginia) Board of Educations compliance with the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. The Morgans contended that because an Individualized Education Program

("IEP") developed in May 2000 for Bradleys 2000-2001 school year

was inappropriate under the Act, they were entitled to have Bradley

placed in an out-of-state private residential school and have the State

reimburse them their annual costs of $27,800. While the hearing officer agreed that the IEP for Bradley was inappropriate, she directed the

Morgans to follow an administrative process for developing a new

IEP before any out-of-state placement would be considered. The hearing officer also concluded that the Morgans had failed to establish the

need at that time for out-of-state placement and also the reasonableness of its cost.

The district court granted summary judgment for Greenbrier

County, and, for the reasons that follow, we affirm.

I

During the 1999-2000 school year, Bradley was in the sixth grade

at Greenbrier County (West Virginia) Elementary School. Because

Bradley had previously been diagnosed as dyslexic, he received both

special education and regular education part time.

On May 23, 2000, the Morgans and their son attended a meeting

scheduled to develop Bradleys 2000-2001 IEP. The Morgans were

dissatisfied with the IEP developed, and, based both on Bradleys past

lack of educational progress as well as the process followed in devel-

MORGAN v. GREENBRIER COUNTY WEST VIRGINIA

oping the IEP, they requested a due process hearing to review the

2000-2001 IEP. At the same time, the Morgans unilaterally enrolled

Bradley in a six-week summer course at the Oakland School in Virginia, a residential school that specializes in teaching dyslexic students.

The due process hearing was conducted before an impartial hearing

officer on July 27 and 28, 2000, in Lewisburg, West Virginia, and on

August 25, 2000, following the hearing, the hearing officer issued a

lengthy written decision that included detailed findings of fact and

conclusions of law. In her decision, the hearing officer agreed with

the Morgans that the IEP developed for Bradley for the 2000-2001

school year was not appropriate in that it was not reasonably calculated to provide Bradley with educational benefit. While the hearing

officer found "serious procedural deficiencies," she nonetheless concluded that these deficiencies did not cause Bradley to lose "educational opportunity." The officer noted that because the Morgans

"elected to file a due process [hearing request] immediately, no IEP

committee meeting could be reconvened as [had been] offered by the

County." To remedy this short-circuiting of the process, the hearing

officer directed that the IEP committee meet as soon as possible, but

in any case within 15 days of its order, to prepare an appropriate IEP

for Bradleys 2000-2001 school year. Moreover, the hearing officer

detailed the process that had to be followed. The hearing officer concluded that only if the IEP committee concluded that Greenbrier

County schools could not, based on evaluations, provide Bradley with

an educational benefit in Greenbrier County, should the IEP committee consider residential placement as requested by the Morgans.

With respect to the Morgans request that Bradley be placed forthwith at an out-of-state residential school, the officer concluded that

such a placement was not justified, and to order such a placement

without pursuing a revised IEP would ignore the Acts requirement

that, "to the greatest extent possible, children are to be educated in the

least restrictive environment." See 20 U.S.C. 1412(a)(5)(A). In addition, the hearing officer pointed out that the Morgans failed to provide

any evidence "as to the reasonableness of the costs (approximately

$25,000 per year) of the parents proposed placement."

Similarly, with respect to the Morgans request for unilateral placement of Bradley at the Oakland School summer program, the officer

MORGAN v. GREENBRIER COUNTY WEST VIRGINIA

concluded that the Morgans had not presented sufficient evidence for

such a placement and for the reasonableness of its costs.

Finally the hearing officer rejected Bradleys claim for "compensatory education." Noting that compensatory education is a remedy "occasionally used when the County schools knew or should have known

that the students IEP was inappropriate and when the student was not

receiving more than de minimis educational benefit or when the

County schools acted in bad faith," the hearing officer found that

those circumstances had not been demonstrated in this case. The officer stated that the Countys conduct amounting to procedural deficiencies did not "appear to be an act of deliberate indifference

towards the parents IDEA rights."

The Morgans commenced this action under the IDEA, 20 U.S.C.

415(i)(2)(A), to review the hearing officers decision (1) to refuse

to approve the placement of Bradley at the Oakland School for the

2000 summer session, the 2000-2001 school year, and such years

thereafter as necessary, and (2) to deny Bradleys claim for reimbursement for expenses incurred in sending Bradley to the Oakland

School. On the motion of Greenbrier County, the district court

granted summary judgment to the County, essentially agreeing with

the hearing officer on the issues raised. From the district courts judgment, this appeal followed.

II

Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act ("IDEA"),

State eligibility for federal funding requires the State to insure that a

free appropriate public education is available to all disabled children

between ages 3 and 21 residing in the State. 20 U.S.C.

1412(a)(1)(A). To provide a free appropriate public education to a

disabled student, a local educational agency must develop an appropriate "Individualized Education Program" ("IEP") tailored to the

individual student. Id. 1412(a)(4), 1414(d); Bd. of Educ. of Hendrick Hudson Central Sch. Dist. v. Rowley, 458 U.S. 176, 181-82

(1982). The IDEA provides parents the opportunity to participate in

the development of the IEP, 20 U.S.C. 1414(d)(1)(B), (d)(3), and

provides them procedural safeguards, id. 1415.

MORGAN v. GREENBRIER COUNTY WEST VIRGINIA

The required procedural safeguards include the opportunity for parents to present complaints with respect to the States provision of a

free appropriate public education or to the identification, evaluation,

or educational placement of their disabled child. 20 U.S.C.

1415(b)(6). Parents may pursue their complaint further by requesting an "impartial due process hearing," which, in West Virginia, is

conducted by the State educational agency. Id. 1415(f)-(g); W. Va.

Code St. R. 126-16-8.1.11. "Any party aggrieved by the findings

and decision" made by the State educational agency is given the right

"to bring a civil action with respect to the complaint presented" to the

agency. Id. 1415(i)(2)(A). In the judicial proceeding, the administrative findings of fact are considered "prima facie correct, and if a

review court fails to adhere to them, it is obliged to explain why."

MM ex rel. DM v. Sch. Dist. of Greenville County, 303 F.3d 523, 53031 (4th Cir. 2002). Stated differently, "the deference due the decision

of the underlying State administrative process requires that the party

challenging the administrative decision bear the burden of proof"

before the district court. Tice v. Botetourt County School Board, 908

F.2d 1200, 1206 n.5 (4th Cir. 1990) (citing Spielberg v. Henrico

County Public Schools, 853 F.2d 256, 258 n.2 (4th Cir. 1988)).

In this case, the hearing officer concluded that Bradleys 20002001 IEP, developed for Bradley on May 23, 2000, was not appropriate, and she directed the IEP committee to meet within 15 days to prepare an appropriate one. She also specified the procedures that had to

be followed in the renewed effort. The hearing officer concluded that

only if the IEP committee concluded, after pursuing the specified procedures, that Bradley would not receive educational benefit within

county schools could the IEP committee consider an out-of-state

placement, as the Morgans requested. The Morgans have advanced no

reason why this ruling was not appropriate and why they should not

have completed the specified administrative process before commencing this action. Indeed, they were essentially vindicated in their claim

that the original IEP was inappropriate and that a new one should be

developed. Accordingly, we find no error by the district courts affirmance of this ruling.

With respect to the Morgans claims that Bradley should be placed

at an out-of-state residential school and that the State should reimburse the Morgans for the cost, we agree with the district court and

MORGAN v. GREENBRIER COUNTY WEST VIRGINIA

the hearing officer that the Morgans have essentially jumped the gun.

They have failed to demonstrate why only an out-of-state placement

was appropriate and why they should not be required to proceed with

the process ordered by the hearing officer. In addition, the Morgans

presented no evidence sufficient to justify their placement of Bradley

at an out-of-state residential school for the summer of 2000. Extended

school year services are not necessary to a free appropriate public

education under the IDEA unless "the benefits a disabled child gains

during a regular school year will be significantly jeopardized if he is

not provided with an educational program during the summer

months." MM ex rel. DM, 303 F.3d at 537-38. And with respect to

both the summer placement and the proposed permanent placement

at the Oakland School, the Morgans failed to present any evidence to

justify the reasonableness of the costs. Finding no error below, we

affirm.

We must note, however, that our judgment is a narrow one, ruling

only on the limited issues placed before us by the Morgans complaint. We do not have before us the issue of the appropriateness of

any IEP that was developed or any actions taken after the due process

hearing. Thus, we do not rule on whether, in the appropriate circumstances, the Morgans might not still be entitled to some reimbursement or other relief.

For the reasons given, the judgment of the district court is

AFFIRMED.

WILLIAMS, Circuit Judge, concurring in part and dissenting in part:

Although I agree with my colleagues that VM1 has "essentially

jumped the gun" by failing to attend the second IEP meeting ordered

by the hearing officer, I write separately to explain why I believe that

VM must follow the process ordered by the hearing officer.2 I also

1

In order to protect the privacy of the minor child and his family, I

refer to the child as BM and the parents collectively as VM.

2

The majority styles its opinion as an affirmance of the district courts

grant of summary judgment, but, when a plaintiff fails to exhaust admin-

MORGAN v. GREENBRIER COUNTY WEST VIRGINIA

write to state my disagreement with the majoritys treatment of the

district courts decision regarding VMs claim for compensatory education. Additionally, because VM is likely to pursue reimbursement

for placing BM at the Oakland School in the future, I take this opportunity to note the proper legal standards under the IDEA to be considered when determining if a proposed parental placement is

appropriate.

The IDEA requires that parties exhaust their administrative remedies before filing suit. 20 U.S.C.A. 1415(i)(2) (West 2000). At oral

argument, VM nonetheless argued that exhaustion should not be

required here because the objections made to the first IEP will likely

be repeated during any future IEP meeting. In a similar situation, the

Tenth Circuit explained that "nothing in the IDEA . . . states that a

plaintiff need not exhaust administrative remedies if his objection to

a second IEP is the same as his objection to his first IEP." Urban v.

Jefferson County Sch. Dist. R-1, 89 F.3d 720, 725 (10th Cir. 1996).

Likewise, even assuming VMs objections to BMs second IEP would

have been the same as the objections to the first i.e., the IEP would

not recommend placement in the Oakland School an exhaustion of

remedies is still required.3

Because a childs education is something near the heart of all parents, a parent aggrieved by an adverse ruling in this context might

istrative remedies, the typical disposition is a dismissal of the action for

lack of subject matter jurisdiction. See MM ex rel. DM v. School Dist. of

Greenville County, 303 F.3d 523, 536 (4th Cir. 2002). Because summary

judgment is a ruling on the merits, affirming the district courts grant of

summary judgment in this case may bar VM from relitigating his reimbursement claim in a later action. See generally Grausz v. Englander,

321 F.3d 467, 472 (4th Cir. 2003) (explaining that res judicata requires

a prior final decision on the merits). I believe the appropriate action, consistent with the majoritys approach, is to dismiss this action for lack of

subject matter jurisdiction

3

Although it may seem inequitable to require a second IEP meeting

where a plaintiff argues that second meeting was ordered solely because

of the legal errors made by the hearing officer when determining if the

parental placement was proper, the IDEA does not provide an exception

to the exhaustion requirement for this circumstance.

MORGAN v. GREENBRIER COUNTY WEST VIRGINIA

find it difficult to understand the application of a rigid exhaustion

requirement when the result is a possible loss of further educational

opportunity. The IDEA, however, provides a panoply of procedural

safeguards and administrative remedies based on Congress belief that

courts should not "substitute their own notions of sound educational

policy for those of the school authorities which they review." Bd. of

Educ. v. Rowley, 458 U.S. 176, 206 (1983). Given this Congressional

intent, it would be improper to second-guess the school districts decisions before they are made. If this system seems burdensome, the

remedy lies in Congress, not the courts. Because VM "jumped the

gun," the administrative process was unable to run its course in this

case. I agree with the majority that VM should convene a second IEP

meeting with the school district, create a second IEP, and then, if the

concerns are not resolved, institute a civil action after that IEP is

reviewed at a due process hearing.

As for VMs compensatory education claim, VM has exhausted

administrative remedies. I thus dissent from my colleagues failure to

address the district courts disposition of this claim. Compensatory

education is "educational services ordered by the court to be provided

prospectively to compensate for a past deficient program." G ex rel.

RG v. Fort Bragg Dependent Schs., 343 F.3d 295, 308 (4th Cir.

2003). The hearing officer, in her final order, clearly stated that an

award of compensatory education was improper and, as shown by the

fact that the district court addressed the claim, VMs complaint sufficiently stated a request for compensatory education. Accordingly, VM

properly instituted a civil action on that claim. See 20 U.S.C.A.

1415(i)(2) (West 2000); Urban, 89 F.3d at 725 (reviewing a claim for

compensatory services, after holding that other IDEA claims had not

been exhausted).

The district court granted summary judgment on that claim, stating

that "case law does not address the type of prospective relief being

sought in this case." (J.A. at 586.) Unfortunately, the district court did

not have the benefit of our opinion in G v. Fort Bragg, 343 F.3d at

309, at the time it issued its order. In G v. Fort Bragg, we held, in

accord with our sister circuits, that "the IDEA permits an award of

[compensatory education] in some circumstances." Id. Because the

district court believed that claims for compensatory education were

not cognizable under the IDEA, the district court did not examine the

MORGAN v. GREENBRIER COUNTY WEST VIRGINIA

merits of the claim, and I likewise refrain from doing so. I only note

that, because the hearing officer issued a final order categorically

denying compensatory education, VM properly exhausted the administrative remedies with respect to that claim. I would thus reverse the

district courts grant of summary judgment on this claim and remand

the claim for further proceedings in light of G v. Fort Bragg.

Finally, because VM is likely to pursue reimbursement for private

educational expenses in the future, and the majority opinion does not

foreclose such a possibility, I want to address two areas where the

legal standards to be applied in these circumstances differ from those

typically employed under the IDEA.4 Reimbursement of private education expenses under IDEA is appropriate when the reviewing court

finds that: (1) the public schools placement was not providing the

child with a free appropriate public education; and (2) the parents

alternative placement was proper under IDEA. Sch. Comm. v. Dept

of Educ., 471 U.S. 359, 369-70 (1985).

Congress passed the IDEA in order to give disabled and handicapped children access to public schools. See Sch. Comm., 471 U.S.

at 373. In Carter v. Florence County Sch. Dist. Four, 950 F.2d 156,

163 (4th Cir. 1991), affd on other grounds, 510 U.S. 7 (1993), however, we held that, despite the congressional intent to give disabled

children the ability to attend public school, the standard for determining the appropriateness of a parental placement in a private school is

not overly stringent. We explained "when a public school system has

defaulted on its obligations under the Act, a private school placement

is proper under the Act if the education provided by the private

school is reasonably calculated to enable the child to receive educa4

Specifically, at the due process hearing, the hearing officer cited to an

unpublished disposition dealing with residential care outside of school,

Board of Educ. v. Brett Y ex rel. Mark Y, 1998 WL 390553, 155 F.3d 557

(4th Cir. 1998), for the proposition that reimbursement was proper only

where the "educational benefits which can be provided through residential care are essential for that child to make any progress at all." (J.A. at

543.) The hearing officer also believed that the least restrictive environment test, 20 U.S.C.A. 1412(5)(A) (West 2000), strictly applied to

parental placements. (J.A. at 544.)

10

MORGAN v. GREENBRIER COUNTY WEST VIRGINIA

tional benefits," Carter, 950 F.2d at 163 (quoting Rowley, 458 U.S.

at 207), a standard not applied by the hearing officer.5

Additionally, in Carter, we expressed strong doubt as to whether

the least restrictive environment requirement of the IDEA, 20

U.S.C.A. 1412(5)(A) (West 2000), applies to parental placements.

Carter, 950 F.2d at 160. We noted "the school district has presented

no evidence that the policy was meant to restrict parental options."

Id. (emphasis in original). Moreover, other circuits addressing the

issue have held that the least restrictive environment requirement does

not apply with the same force to parental placements as it does to

placements advocated by school districts. See M.S. ex rel. S.S. v. Bd.

of Educ., 231 F.3d 96, 105 (2d Cir. 2000) (stating that mainstreaming

"remains a consideration" but noting that parents "may not be subject

to the same mainstreaming requirements"); Cleveland HeightsUniversity Heights Sch. Dist. v. Boss, 144 F.3d 391, 399-400 (6th Cir.

1998) (failure to meet mainstreaming requirements does not bar reimbursement). As we have explained, "the Acts preference for mainstreaming was aimed at preventing schools from segregating

handicapped students from the general student body." Carter, 950

F.2d at 160 (emphasis in original). Although we have not definitively

resolved the proper role of the mainstreaming requirement when considering parental placements, contrary to the hearing officers

approach,6 it is clear that requirement should not be applied in the

strictest sense.

In sum, I concur in my colleagues analysis of the reimbursement

claim, but I would have clarified that the appropriate disposition of

the claim is a dismissal for lack of subject matter jurisdiction.

5

Instead, the hearing officer applied the standard applicable when

determining whether services beyond the regular school day are appropriate under the IDEA. (J.A. at 543) (citing Board of Educ. v. Brett Y ex

rel. Mark Y, 1998 WL 390553, 155 F.3d 557 (4th Cir. 1998) (unpublished) (holding reimbursement of extended school year services proper

where "educational benefits which can be provided through residential

care are essential for that child to make any progress at all").

6

The due process hearing officer strictly applied the least restrictive

environment test when reviewing VMs request for reimbursement during the hearing. (J.A. at 544.)

MORGAN v. GREENBRIER COUNTY WEST VIRGINIA

11

Because VM did exhaust the administrative remedies with regard to

the claim for compensatory education, I would reverse the district

courts grant of summary judgment on that claim and remand for further proceedings.

You might also like

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- GUITAR MUSIC CULTURES IN PARAGUAYDocument5 pagesGUITAR MUSIC CULTURES IN PARAGUAYHugo PinoNo ratings yet

- CSEC POA CoverSheetForESBA FillableDocument1 pageCSEC POA CoverSheetForESBA FillableRushayNo ratings yet

- ME010 805G01 Industrial Safety Electives at Mahatma Gandhi UniversityDocument2 pagesME010 805G01 Industrial Safety Electives at Mahatma Gandhi Universityrajeesh4meNo ratings yet

- Address:: Name: Akshita KukrejaDocument2 pagesAddress:: Name: Akshita KukrejaHarbrinder GurmNo ratings yet

- Portfolio in Child Adolescent and Learning PrinciplesDocument90 pagesPortfolio in Child Adolescent and Learning PrinciplesKing Louie100% (3)

- Action Research Title: Pictionary: A Tool in Introducing Filipino Sign Language To Out of School Youth Who Is DeafDocument3 pagesAction Research Title: Pictionary: A Tool in Introducing Filipino Sign Language To Out of School Youth Who Is Deafkishia peronceNo ratings yet

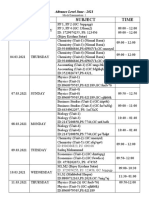

- Mock Examination Routine A 2021 NewDocument2 pagesMock Examination Routine A 2021 Newmufrad muhtasibNo ratings yet

- The Journeyto Learning Throughthe Learning StylesDocument93 pagesThe Journeyto Learning Throughthe Learning Stylesastria alosNo ratings yet

- ASEAN Quality Assurance Framework (AQAF)Document18 pagesASEAN Quality Assurance Framework (AQAF)Ummu SalamahNo ratings yet

- AFMC MBBS Information Brochure 2019Document27 pagesAFMC MBBS Information Brochure 2019riteshNo ratings yet

- Tesco Training and DevelopmentDocument3 pagesTesco Training and DevelopmentIustin EmanuelNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Development and Comprehension Skills Through Word Games Among Grade 4 LearnersDocument11 pagesVocabulary Development and Comprehension Skills Through Word Games Among Grade 4 LearnersPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Behavior Management Through AdventureDocument5 pagesBehavior Management Through AdventureInese BerzinaNo ratings yet

- 13.2.3a Practicing Good SpeakingDocument9 pages13.2.3a Practicing Good SpeakingNieyfa RisyaNo ratings yet

- Causation and Explanation: Topics from the Inland Northwest Philosophy ConferenceDocument335 pagesCausation and Explanation: Topics from the Inland Northwest Philosophy ConferenceMaghiar Manuela PatriciaNo ratings yet

- Officialresumesln 2013Document3 pagesOfficialresumesln 2013api-355089316No ratings yet

- Master Your Teamwork SkillsDocument16 pagesMaster Your Teamwork Skillsronnel luceroNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Critical Review Form Qualitative StudiesDocument12 pagesGuidelines For Critical Review Form Qualitative StudiesTopo SusiloNo ratings yet

- DLL EnglishDocument20 pagesDLL EnglishNoreen PatayanNo ratings yet

- tmp5738 TMPDocument16 pagestmp5738 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- 03 - Graphing LogarithmsDocument4 pages03 - Graphing LogarithmsKirk PolkaNo ratings yet

- Bar Graph Exercise Grade 3 - Búsqueda de GoogleDocument1 pageBar Graph Exercise Grade 3 - Búsqueda de GoogleAnita BaltierraNo ratings yet

- Data and Graphs Project Advanced MathDocument8 pagesData and Graphs Project Advanced Mathapi-169858360No ratings yet

- Rina Membership Application Form - Fellow and MemberDocument4 pagesRina Membership Application Form - Fellow and MembermealosNo ratings yet

- 15 - Unit Test 1Document1 page15 - Unit Test 1gildae219100% (1)

- Studies in Philippine Linguistics PDFDocument59 pagesStudies in Philippine Linguistics PDFJ.k. LearnedScholar100% (1)

- Description: Tags: SCH050708quarter3Document605 pagesDescription: Tags: SCH050708quarter3anon-844996No ratings yet

- Youth For Environment in Schools OrganizationDocument2 pagesYouth For Environment in Schools OrganizationCiara Faye M. PadacaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Communicative Competence ComponentsDocument7 pagesAnalysis of Communicative Competence ComponentsAinhoa Sempere IlazarriNo ratings yet

- Sally-Mangan SADocument30 pagesSally-Mangan SAAlex NichollsNo ratings yet