Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ijeefus - Involuntary Resettlement Policy and Praxis in Kenya

Uploaded by

TJPRC PublicationsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ijeefus - Involuntary Resettlement Policy and Praxis in Kenya

Uploaded by

TJPRC PublicationsCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Environment, Ecology,

Family and Urban Studies (IJEEFUS)

ISSN(P): 2250-0065; ISSN(E): 2321-0109

Vol. 6, Issue 3, Jun 2016, 23-44

TJPRC Pvt. Ltd.

INVOLUNTARY RESETTLEMENT POLICY AND PRAXIS IN KENYA:

AN EVALUATION OF JUST TERMS OF COMPENSATION

SALOME L. MUNUB, O. A. KAKUMU & WINNIE MWANGI

School of Built Environment, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

ABSTRACT

This paper assessed just terms of compensation in involuntary resettlement policy and praxis in Kenya.

Examination of policy on assessment of value identified the parity gap in compensation between the sociologist and

economist approaches. An extrapolation of policy frameworks to a theoretical model anchored on traditional social

formations conceptualized just terms of compensation for involuntary resettlement. The exploratory study of NairobiThika highway discoursed on epistemology and philosophies of justice within constitutionalism of prompt payment in full

of just compensation. The research methodology entailed subjecting structured questionnaires to sampled strata of

project affected persons. Variables under measurement premised on Cernias (2000) risk, impoverishment and

reconstruction model to establish the level of satisfaction with the compensation praxis and inclusion of socio-cultural

Regression and Pearson Bivariate Coefficients techniques concluded that policy and legal frameworks fell short in just

compensation for involuntary resettlement in Kenya. A recompense model is recommended to bridge the impoverishment

gap in sociologist and economist approaches.

KEYWORDS: Involuntary Resettlement, Compulsory Acquisition, Just Compensation, Social Disarticulation, Livelihood

Restoration, Kenya

Original Article

and economic considerations in policy. A mixed data analyses strategy combining the Analysis of Variance, Multiple

Received: Apr 22, 2016; Accepted: Apr 27, 2016; Published: May 06, 2016; Paper Id.: IJEEFUSJUN20164

INTRODUCTION

1.0 Background and Aim of the study

Involuntary resettlement is the forced relocation of people from familiar habitation to unfamiliar areas.

The causes range from environmental disasters, political instability, need for preservation of eco-sensitive areas to

socio-economic development for public benefit. Since not all involuntary resettlement cases warrant compensation,

this paper focussed on compensation for involuntary resettlement occasioned by government initiatives for public

projects as defined in the Constitution and Land Laws of Kenya (GoK 2010, 2012 a).

The coercive power of eminent domain over land is recognized the world over; the socialist perspectives

of acquisition at no compensation (Simkin 1997, Schoefield 2006), capitalistic advocacy for compensation

(Almond and Plimmer, 1997) and a hybrid of socio-capitalist orientations (Denyer-Green 1989, Chan 2003). In

Kenya, while alienation of land was marginally compensated, compulsory acquisition used the Land Acquisition

Act of India of 1894, majorly for the Uganda Railway to entice the capitalist mode of production (CMP) in opening

up the hinterland. Having ignored the traditional familial formation, the praxis for land alienation became

synonymous with compulsory acquisition and has remained an enigma within legal ideologies and traditional ethos

in search for a just recompense (see GoK 1934, Okoth Ogendo 1991, Kiamba 1989). For a pragmatic solution, this study

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

24

Salome L. Munub, O. A. Kakumu & Winnie Mwangi

borrowed heavily from Cernias (2000) eight-tier model on risk, impoverishment and reconstruction in involuntary

resettlement as a prism for social disarticulation towards just compensation. Data analyses was against objects of

involuntary resettlement in the National Land Policy (NLP), the Constitution and the Land Act 2012 of Kenya (GoK 2009,

2010, 2012a).

Power of eminent domain applied on Nairobi-Thika highway resulted to displacement and involuntary

resettlement of project affected persons (PAPs). At the time of study in year 2014, official records from the Ministry of

Lands indicated that out of the rounded compensation of 5.2 billion shillings, some 2.0 billion still pended disbursement to

PAPs despite completion of the project in year 2010. This project transitioned through the pre-land reform period,

necessitating an evaluation of compensation praxis constitutionally denoted as prompt payment in full of just

compensation. This was in regard to PAPs and dependants ideologies and litigations pending in court evaluating

compensation in policy and praxis.

2.0 PROBLEM STATEMENT

The study by Syagga and Olima (1996) on The Impact of Land Acquisition on Project Displaced Persons

Households; - The Case of the Third Nairobi Water Supply Project Kenya, findings confirmed that statutory frameworks

and compensation values fell short of the socio-cultural and economic expectations of project displaced persons (PDPs) by:

Specific quantifiable economic concerns including conveyance taxes in new settlement areas and travelling

expenses were ignored.

Social formations emanating from cultural praxis including social-economic self-help costs, social amenities in

new areas, educational cost of new schools and purchase of food before growth of new crop.

Adverse changes in income levels and negative economic effects on partly acquired land. Training and extension

services for economic rehabilitation were not provided.

Traditional access to land held in trust was ignored. Syagga (2009) noted that registration conferred a maxima of

five members to land holdings despite customary unitary engagement for all members. Re-assessment of intra and

inter-household equity was ignored resulting to land compensation paid to heads of house-holds as opposed to

cultural entitlement.

Lack of counselling for PAPs leaving cultural attachments like burying grounds and shrines.

Protracted court cases (some taking ten years) contesting amount of compensation awarded. Even after the

determination, the payment process remained bureaucratic and often, compensation money was not available.

Though Syagga and Olima (1996) noted inadequacies in policy and compensation praxis as contributing to social

disarticulation, they did not advance a quantifiable mitigating compensation model. Furthermore, empirical evidence on

quest for just compensation by scholars like Wilsen (2011) note that, in the resettlement of communities displaced by the

three Gorges Dam along the Yangtze river in China, the Asian Development Bank report of 2009 indicated lack of risk

strategy for the prevention of impoverishment. The government policy resulted to resettlement of ethnic minorities within

hostile communities. The assessed values, cultural-economic praxis and social networks were never computed save for

developments. Furthermore, Cernias (1999) paper on Why Economic Analysis Is Essential to Resettlement; - A

Sociologist's View, compensation for economic livelihood was least addressed in research, analysis and financial planning.

Impact Factor (JCC): 3.0965

NAAS Rating: 3.63

Involuntary Resettlement Policy and Praxis in Kenya: An Evaluation of Just Terms of Compensation

25

Displacement and involuntary resettlement are relegated to the project tail end or appended as a dysfunctional by-product

non-core to any project. Basically, Ngongola (1992), Menezes (1991) and Cernia (1999) argue the omission as inbuilt in

conventional project analyses models that concentrate on investment yields as opposed to livelihood restoration. Kothari

(1996) concludes that equity in compensation will remain marginal, palliative and temporary due to misdemeanours in

policy frameworks that ignore the broader socio-cultural, economic and political issues.

Anthropologists are now bisecting justice and fairness in compensation of involuntary resettlement with a 3600

fulcrum approach in resettlement planning, having noted that realtors and other practitioners limit compensation to

legislation. Despite scholarly discourses on shortcomings within legal frameworks, none has suggested a modelled

proposition for recompense that seeks to bridge the identified gaps. Therefore, Cernias (2000) eight-tier impoverishment

framework is an illustration of the World Bank guidelines that redefined the socio-cultural and economic variables ignored

in legislated compensation. Therefore, the study derived the objectives as:

To review and examine adequacy of policy frameworks for just terms of compensation in involuntary

resettlement.

To develop a just terms of compensation model for involuntary resettlement.

This study hypothesized that:H0: Just terms of compensation are adequate in policy frameworks and compensation praxis

In involuntary resettlement in Kenya.

Hu: Just terms of compensation are not adequate in policy frameworks and compensation praxis in involuntary

resettlement in Kenya.

3.0 LITERATURE REVIEW

This section defined involuntary resettlement, displacement and policy frameworks on just compensation in

Kenya.

Involuntary Resettlement in Compulsory Acquisition

Agbola and Jinadu (1997) describe involuntary resettlement as an officially sanctioned act that has harmful

consequences on affected persons. It is disruptive and discriminative socially and economically in nature. Therefore,

compulsory acquisition is the coercive take-over of private land by government for public purposes. While alienation

presumes government possession of land, compulsory acquisition presupposes possession is private or communal, against

the proprietors will (Harbeson 1973; Okoth-Ogendo 1991). However, inverse acquisition allows the proprietor to compel

the government to reflect purchase by will to bypass negative socio-cultural and economic effects of compulsory purchase

(Almond and Plimmer, 1997). In either case, the remaining land may be uneconomical or incompatible with the new

development, an issue ignored in compensation matrices. Furthermore, incremental challenges such as conveyance costs,

untraced owners and refusal to grant entry before conveyance, escalating to litigious claims in a policy abyss (Syagga and

Olima, 1996).

Legal approaches necessitated compulsory acquisition, otherwise to which access or use of land would be illegal.

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

26

Salome L. Munub, O. A. Kakumu & Winnie Mwangi

The acquiring bodys activity would be trespass and the action would be ultra vires and unlawful (Plimmer 2007). The

law precludes these powers under constitutional and statutory safeguards but on pre-condition of just compensation

(Lawrence et al. 1976, Denyer-Green 1989). This advances Ndegwas (1985) argument of regional economic prosperity

through equitable sharing of impoverishment risks by nationally spreading the effects of dislocation and resettlement to

cushion dependency losses vis-a-vis the public gain. As the economist De Soto (1994) argues, apart from being collateral

to borrowing, land titles increase property values and accessibility to capital at individual micro-economic level against the

states macro-economic duty.

The Effects of Involuntary Resettlement

The panacea for development is involuntary resettlement, but the nemesis of compulsory acquisition is

involuntary resettlement, synchronized by justice in compensation. According to the Office of High Commissioner on

Human Rights (OHCHR 1996-2012) report, involuntary resettlement has negative socio-cultural and economic impacts

occasioned by displacement from familiar tenure definitions of occupation, use, abuse and disposition on land. Due to

displacement, impoverishment exacerbates the unwillingness to relocate (Ngongola, 1992; IFC 2007, De Wet 1994). This

impoverishment is mirrored in Cernias (1996, 2000) ethnographic observations of social disarticulation. In support, Umeh

(1973) connotes compulsory acquisition as coercive and inferior to open purchase. The subsequent resettlement deprives

communities access to inherent social-cultural and economic facilities, cultural sites, social networks and common areas

(Thomas 2002; Mdolongwa 1998).

Equally contentious is the adequacy of compensation for the acquired property (Burrows 1991; Elman 1968,

Braun 2005). Umeh (1973) and Rwiza (2010) observe that traditionally, individual compensation was co-joined in the

public purpose and alternative land needed not measure in quantum or comparability. As historically noted, compensation

is still bedevilled by untitled replacement land, transition trauma, family disintegration and conflict with host communities

(Okoth-Ogendo 1991). To this extent, Kothari (1996) observes PAPs uncertainty in involuntary resettlement due to lack of

information on impacts and dependant expediencies borne by inadequate policy frameworks.

According to Ndegwa (1985), other than the economic drive, development defines socio-political benefits that

balance socialism as human modules and capitalism as production modules unveiling civility. Hill (1976) notes that

infrastructure is the highway to civility, without which societies would remain backward, thereby justifying the States

legal instruments on coercive power. Circumspectively, the concept of private property contradicts the dictum of statutory

takeovers and is the crux of just compensation at constitutional and moral levels (Burrows 1991; Elman 1968; Braun

2005). Therefore, development takes a nationalistic character created by political ideologies to overcome ethnic, linguistic

and cultural differences in recompense structures (Ndegwa 1985). In turn, Harbeson (1973) argues that in Kenya,

nationalism was borne from breakdown of traditional cultures ignored by imperial tendencies that favoured CMP

structures. Resultant, was scarcity of land, unemployment and food shortage facing developing countries when actualizing

the national development programmes (Ndegwa 1985; Harbeson (1973).

Compensation Policy for Involuntary Resettlement

Since the concept of compensation is borne out of power of eminent domain, therefore, compulsory acquisition is

legally claimable (Kiamba, 1989). Compensation for involuntary resettlement is a constitutional right provided the world

over as pre-requisite to compulsory purchase (Nuhu and Aliyu 2009; Mendie et. al. 2010). Therefore, involuntary

Impact Factor (JCC): 3.0965

NAAS Rating: 3.63

Involuntary Resettlement Policy and Praxis in Kenya: An Evaluation of Just Terms of Compensation

27

resettlement hinges on conjectures of justice in compensation however, complexity in compensation arises from

distinguishing between genuine dispossession and speculative claims in excess of property market values (Mangioni 2008,

GoK 2012a).

In exemplifying structured and un-structured policy frameworks, the study reviewed compensation praxis in

China and Brazil. In China, land is vested in either the state or collective ownership thus social disarticulation is ignored in

resettlement compensation as observed in the Three Gorges Dam Project in Yutang Province (Wilsen, 2011). Ding (2005)

denotes the 1949 land-use law as regulating on improvements in urban areas and transactory rights in rural areas. Wilsen

(2011) adds that compensation is based on annual average output value of crop, ironically vested in the governments

agricultural pricing policy capitalized at 0.25%, making it uncompetitive in the market. Since rural China has no market

comparable, living standards decrease upon displacement, increase in dependency on hakou (licenses) status and

expropriatee resettlement in hostile host communities. However, Ding (2005) observes that policy frameworks provide job

placement and a geographically bonded hakou status that accesses social benefits and public goods at subsidized levels for

dependents.

Wilsen (2011) notes that China is continually improving resettlement policy by enhancing development

opportunity using project generated funds for livelihood restoration through improved impact identification processes.

Implementation challenges included long-distance resettlement that broke familial composition, lag times in livelihood

improvement and a production economy that ignored subsistent agriculturists (Croll, 1999). By contrast, displacement in

Kenya is oriented towards cash compensation that resulting to an impoverishment vacuum identified as social

disarticulation of PAPs and their dependents.

In comparison, land reforms in Brazil empowered the government to excise holdings exceeding 500 acres for

redistribution to the land-less. The land inequality placed 45% of total land as owned by 1% of the people (Kane, 1999;

Lambais, 2008). Therefore, the World Banks market based reform programme extended loans for purchase of excess land

by the government for redistribution and restitution to the landless majority (Frank, 2002). However, Lambais (2008)

observes that despite these reforms, non-crystallization of the land policy in addressing broad socio-cultural and economic

issues at macro-economic levels saw failure of the programme. Reforms were incomplete due to non-institutionalization of

equitable access by small land-owners (minifundio) into large latifundios. The informal acquisition and compensation

policies resulted to impoverishment to both the minifundio and latifundio owners (Janvry and Sadoulet, 2002). This

observation amplified the studys focus that evaluated land policies on just terms of compensation premised on concepts of

equity.

In Africa, the tenure system anchored on right of avail of land to all clan members who deduced their common

and individual rights (Kalabamu, 2000). As social constructs, no one was landless, while perpetuity of individual rights

was subject to communal access and conformity with sustainable systems of disposition (De Wet 2001; Obeng-Odoom,

2012). Compensation for communal land was replaced with virgin lands, however, with time, imperialism re-defined

cultural compensation approaches with superseding CMP economic models of land use policies (GoK 1934). In this regard,

the Mangioni (2008) model reflects the economist-valuation policy approaches for commonwealth countries.

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

28

Salome L. Munub, O. A. Kakumu & Winnie Mwangi

Source: Adapted from Mangioni (2008)

Figure 1: Total versus Partial Acquisition Approach

The total acquisition is synonymous to purchase while partial acquisition involves excision of part of the land. In

this case compensation value includes:

Severance for land separated or severed into parts thereby increasing the cost of managing the existing

activities, such asranching.

Injurious affection as decrease in value of the un-acquired land such as a highway blocking slip-road access to

property.

Disturbance as interruption and inconvenience to normal activities. A statutory quantum is added to the market

value.

The before and after valuation method conceptualizes the propertys value before acquisition and residual value

after acquisition. Difference between the two is the impact of the acquisition on the retained property and there is a special

diminishing value of the residual land (Lawrence et. al 1976; Westbrook, 1977; Mangioni, 2008). Likewise, the Kenyan

legal framework considers market value, severance, injurious affection and disturbance (15%) to generate the

compensation entitlement. Factors disregarded in the Kenyan model include the urgency of the takeover, special value

assigned to the property arising from the acquisition, the betterment value and finally, claims contravening the law.

Ngau and Kumssa (2004) argue from anthropological perspectives echoing households ideologies on sociocultural and economic issues. Such are reflected in OHCHR (1996-2012) guidelines on dependencies to include, informal

settlements, income streams, proximity to social facilities and livelihood sources. These mirror the United Nations 1948

charter on property rights further supported by donor agencies such as Japan International Co-operation Agency, Africa

Development Bank and World Bank. These agencies enumerate intangible attributes and entitlements of PAPs irrespective

of title ownership and tangible economic damage to land and developments. These attributes of livelihood restoration

illustrated in Table 1 below are adapted from Cernias (2000) model on social disarticulation.

Impact Factor (JCC): 3.0965

NAAS Rating: 3.63

Involuntary Resettlement Policy and Praxis in Kenya: An Evaluation of Just Terms of Compensation

29

Table 1: Concept of Risk, Impoverishment and Reconstruction

Risk

Impoverishment

Landlessness

Expropriation reduces land sizes and

productive systems.

Joblessness

Loss of wage employment

Homelessness

Deprivation of family dwelling units and

cultural space.

Marginalization

Downward mobility from middle to small

sized parcels and a drop in social status.

Decline in health increases mortality.

Negative impact on education and living

standards.

Reduction in farming lands

Food insecurity

Lack of access to common property areas

Loss of common

(grazing lands, forest, water points, social

property assets

amenities)

Loss of social capital, fragmented family

Livelihood

cohesion and kinship groups

restoration

Source: Adapted from Cernia (2000)

Morbidity and

mortality

Reconstruction

Resettle people in similar agro-economic

production zones and provide development

assistance.

Re-employment in project-related roles and

self-employment services.

Assessment of replacement value to

reconstruct houses for evictees.

Psychological, economic and social

marginalization. Build up sustainable

income sources.

Mitigate negative effects on health, hygiene

and education

Avail agricultural extension services.

Advocacy and awareness for host

population reception and social integration

to avoid social conflict

Relocate familial dependencies in

neighbourhood for sustainable livelihoods

Meshing of sociologist perspectives with best praxis modules culminated to the Human Rights Based Approach

(HRBA) models that distinctly extended conventional resettlement praxis to include human rights and livelihood

sustainability in compensation matrices (OHCHR 2006; Gabrielle 2008). Therefore, Cernias eight-tier social

disarticulation framework converges social constructs with rational economic valuation approaches.

4.0 LEGAL FRAMEWORK OF COMPULSORY ACQUISITION IN KENYA

The Carter Commission Report of 1934 defined the framework on exclusion and setting apart of land using

compensatory blocks in lieu of compensation or moneytary exchange topped with 15 % disturbance allowance. Where full

value was paid, no compensatory block was added. By 1934, alienation and compensation for cultivated land was at 2

rupees per acre for 2 acres defined per household and 4 rupees per hut in Kikuyu country. However compensation for other

lands was generally at 50 ruppes per hut, on land-for-land exchange of equal extent or value (GoK 1934; Sorrenson 1967)

From this background, the legal frameworks and patterns of economic development in Kenya justified forceful

eviction of people at no compensation which is now incompatible with reform ideals of equitable access and social security

on land (GoK 2009). According to Article 40 of the Constitution of Kenya, deprivation of property rights for public

purpose requires prompt payment in full of just compensation . Right of access to a court of law . Compensation to be

paid to occupants in good faith who may not hold title to land (GoK, 2010). The Land Act 2012 further provides the

Commission shall make full inquiry into and determine who the persons are interested in the land .. and receive claims of

compensation from those interested in the land (GoK, 2012a).

Therefore, challenges springing from involuntary resettlement require policy re-definition on Constitutional levels

for policy provisions on resettlement (GoK 2010, 2012a). The NLP section 3.6.5 sets out land rights of vulnerable groups,

section 3.6.6 on land rights of the minority while section 3.6.9 recognizes vulnerability of informal settlements in

development control and expropriation as resettlement tools. Surmise, reforms rationalize allocation powers through

equitable, transparent and efficient framework of involuntary resettlement within land administration and management

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

30

Salome L. Munub, O. A. Kakumu & Winnie Mwangi

institutions. This was crystalized by enactment of the Land Act 2012 and the National Land Commission Act 2012 (see

GoK 2009, 2012a, 2012b).

Table 2: Matrix of the Legal Framework on Compensation in Kenya

Statutory Issue

1.Authority

compulsory

acquire land

to

2.Assets

3.Postponement of

Inquiry

and

revocation

of

acquisition

4.Grant of land-InLieu of Cash

5.Notice

and

takeover

periods

urgent

Pre-Reform Policy

Constitution (1969) Article 75 on compulsory

acquisition; Article 117 on setting apart of trust land

and Land Acquisition Act (LAA) Cap 295, 1990)

(repealed) and Trust Land Act Cap 288.

Acquisition authority vested in Commissioner of

Lands

LAA Cap 295 (1990) Part 6A: owner to remove their

plant and machinery if not required for the acquisition

and it shall not be computed for compensation

LAA Cap 295 Part 9 (4A): Non-holding of inquiry

within 24 months of gazettement was deemed

revocation of intention to acquire.

Part 23 provides for compensation of damage upon

withdrawal of acquisition. Though silent on preemptive rights, land was free for allocation to any

person if compensation had been paid

LAA Cap 295 Part 12: land in lieu of monetary

compensation of equivalent value though cash-forland is the praxis.

LAA Cap 295 Part 19 (2): urgent takeover of vacant

arable land in case of urgency after 30 days notice

6.Interest

on

delayed payments

Constitution 1969 Article 75 (1c): for prompt payment

of fair compensation. LAA 295 Part 16(1): interest for

delayed payment at 6% minimum

7.Grievance

redress mechanism

LAA Cap 295 Part 29 (2) The Land Acquisition

Tribunal as the court of first instance. High court to be

the Court of Appeal

8.Re-settlement

Not provided

9.Livelihood

Not provided

restoration.

Source: Field Study (2015)

Post-Reform Policy

Constitution 2010 and Land Act 2012.

Acquisition authority vested in the

National Land Commission. Trust Land

has been converted to community land

awaiting the community land law.

Land Act 2010 Part 110 (3): owner to

remove plant and machinery from site.

The law is silent on who to bear the cost

Land Act Part 112 (4): Allows

postponement over an undefined period.

Part 123 provides for compensation of

damage upon withdrawal of acquisition,

while Part 110(2) pre-emptive rights

reserved for original owners upon

restitution of compensation

Part 114 (2): land-in-lieu of monetary

compensation of equivalent value

though cash-for-land is the praxis.

Section 120 (2): urgent takeover on

arable land after 15 days notice

notwithstanding no award has been

made.

Constitution 2010 (40 (3)): prompt

payment in full of just compensation.

Land Act Part 117 (1): interest on

delayed payment at prevailing bank

rates

Land Act 2012 Part 128 land disputes

directed to the Land and Environment

Court

Section 134 and 135 provides for

resettlement

Not provided

5.0 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This part highlighted the case study design, sampling procedure and data collection, processing and analyses

techniques.

5.1 Case Study of Nairobi-Thika Highway

The Nairobi-Thika highway project highlighted the tangible compensable economic attributes and ignored socioeconomic attributes thereby establishing the gap being evaluated in policy and compensation praxis. According to Neuman

(2011) and Yin (2003), case studies are useful for research on social sciences relevant for policy orientation as opposed to

biological research. It allows empirical exploration of behavioral patterns by drawing inferences and explanations of

phenomena (Yahya, 1976; Yin 2003). Kothari (2008) argues that case study allows for historical analysis and suggests

Impact Factor (JCC): 3.0965

NAAS Rating: 3.63

Involuntary Resettlement Policy and Praxis in Kenya: An Evaluation of Just Terms of Compensation

31

improvement on the concerned social unit, therefore supporting the objectives of this study.

This case study had significant social-cultural and economic impacts arising from acquisition of land in a land

reform period, espousing expropriatee rights in the NLP and Constitution. The project excised land belonging to

institutions, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and households, thereby affecting their social-economic formations.

CHANIA

21

Structures (Except River Bridge)

20 ProposedTHIKA

19

18

17

16

JUJA

1. Flyover at Globe Roundabout (R/A)

2. Flyover at Chiromo R/A

3. Flyover at Ojijo R/A

4. Flyover at Limuru Road Jn

5. Underpass & Flyover at Pangani

6. Overpass & Underpass at Muthaiga

7. Underpass at Mathare Hospital

8. Underpass at Survey of Kenya

9. Overpass at GSU

10. Overpass at Nakumatt

11. Flyover at Kasarani

RUIRU

12. Flyover at Githurai

15

13

13. ROB

14. Underpass at Kahawa Sukari

15. Flyover at Bypass Jn. (Ruiru)

14

GITHURAI

11

9

12

KASSARAN

I

10 RUARAKA

8 SURVEY OF KENYA

7

MATHARE HOSP

3 4 1

MUSEUM

5 PANGANI

GLOBE CINEMA

2

1

NAIROBI

Legend

16. ROB

17. Underpass at Kiganjo Road

18. Underpass at Gatundu Road

19. ROB

20. Underpass at Mangu Village

21. ROB

Project Road

Cross Road

Railway Line

SOURCE: SURVEY OF KENYA TOPO SHEETS

Flyover

Underpass

Overpass

ROB

Figure 2: Lay out Plan of Project Area

The Dual Sign Carriage before the Upgrade

Upgrade at Utalii Section to Eight Lanes

Forest Road Interchange

Shell Petrol Station on Muranga Road with no Access

Compensation Ignored Closure of Business and

Uneconomic use of Remaining Land

Source: GoK (2015) Nairobi-Thika Road Upgrade Project Completion Report

Figure 3: Before and After Pictorial Views of Nairobi-Thika Highway

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

32

Salome L. Munub, O. A. Kakumu & Winnie Mwangi

The research methodology involved sampling stratified clusters of the population. According to Hyndman (2008)

and Mugenda and Mugenda (2003), a research population is a well-defined collection of objects with similar binding

characteristics. The population for the Nairobi-Thika highway was informed by records from the Ministry of Lands

valuation department through Kenya Gazette Notices 6034 and 6035 of 11th July 2008; Notice 1396 of 20th February 2009;

Notice 8748 of 21th August 2010; Notice 5902 of 28th May 2010; Notice 10904 of 17th September 2010; Notice 454 of 21st

January 2011 and Notice 16180 of 23rd December 2011.

While the population frame defined the registered lands, the study ignored the un-identified land owners

comprising 5.5% and whose compensation was deposited in a special compensation account awaiting their identification

(GoK 1990, 2012a). Therefore, sampling was on the population frame comprising 672 items that constituted 94.5% of the

population.

Mugenda and Mugenda (2003) advises that a good sample should truly represent the population, result in a small

sampling error, be viable, economical and systematic in bringing out results applicable to a universe at a reasonable level

of confidence. Therefore, in this study, a sample response rate of 30% is acceptable in representing outcomes and allowing

for non-responsive elements of the population.

Stratified random sampling was applied to households and SMEs, however, due to the small populations of

institutions and policy makers/implementers, a survey was undertaken to avoid losing any attributes (Kothari 2008; Israel

1992).

Table 3: Population and Sample Size for the Nairobi-Thika Highway

Category

Population

Sample size

Percentage Representation

of Population

50%

50%

100%

100%

443

221

Land Owners

187

93

SMEs

30

30 (survey)

Institutions

12

12 (survey)

Implementers

Total

672

356

Source: Kenya Gazette Notices: 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011

5.2 Data Collection

Burns and Grove (2003) define data collection as the systematic gathering of information relevant to the research

problems using methods such as interviews, participant observations, focus group discussion, narratives and case histories.

Two types of data collection methods were applied in this study.

Secondary Data Collection

Literature was reviewed on policy frameworks and best praxis articulated in donor guidelines on various

compensation models. This review included books, journals, periodicals, the Constitution, statutes, regulations and

working manuals to establish the compensation praxis in Kenya. The internet was also used in sourcing for information and

this method assisted in analysing objective one.

Primary Data Collection

Primary data was collected using structured questionnaires, clarified with open-ended questions. The

questionnaires were self-administered on a pick-and-drop basis by two research assistants. Questionnaires are appropriate

Impact Factor (JCC): 3.0965

NAAS Rating: 3.63

Involuntary Resettlement Policy and Praxis in Kenya: An Evaluation of Just Terms of Compensation

33

in confidential collection of information as was used by Syagga and Olima (1996). In addition, questionnaires are an even

stimulus to large population (Somekh and Lewin 2009). Structured questionnaires have the advantage of being less costly,

use less time in data collection and analyses. They obtain objective data by applying same questions and allowing

respondents confidence in anonymity (Kidder 1981; Yin, 2003). While the close-ended questions guided the respondents

answers, the open-ended questions ensured the questions were understood. The questionnaire doubled as an interview

guide for the semi-literate respondents who were assisted by the research assistants. This method analysed objective two.

5.3 Pilot Testing

In order to minimize possible instrumentation error and increase the reliability of the data collected, a pilot study

was conducted to measure the research instruments reliability and validity (Selltiz et. al 1976). A pilot study was

conducted on 5% of the sample to detect any weakness in design and reliability analysis of internal consistency measured

using Cronbach Alpha coefficient. Internal consistency measured the correlations between different items on the same test

or the same sub-scale to test whether several items measuring the same construct produced similar scores. The 29 prompt

questionnaire is discussed in the data analyses section below.

5.4 Data Processing and Analyses Techniques

Data processing involves translating the responses from a questionnaire into a manipulated form to produce

statistics. This involves coding, editing, data entry, categorizing and keying into Statistical Package for Social Sciences

(SPSS) computer software for analysis (Bryman and Cramer, 2001). SPSS produced descriptive and inferential statistics,

derived generalizations that enabled drawing of conclusions on the statistical data analyses, comparison and interpretation.

Descriptive statistics included frequencies and percentiles while inferential statistics included Analysis of

Variance (ANOVA), Pearsons Bivariate Correlation and Multiple Linear Regression. The regression model was used to

observe the effect of an increase of 1 unit (of the independent variable) on the corresponding increase in just compensation

(dependent variable). According to Saunders et al. (2009), the formula of an increase in Y leading to a corresponding

increase in X is:Y=0+ 1X1+ 2X2..............................+ nXn + e ....................

(1.2)

Since we have only two independent variables in our study then:Y=0+ 1X1+ 2X2 + e

Where:

Y = Just compensation praxis

{ i; i=1,2 } = The coefficients for the various independent variables

Xi for;

X1 = Extent to which policy frameworks are just in compensation

X2 = Awareness of the legal framework on just compensation

e is the error margin, normally distributed with mean zero and constant variance.

The data analyses relied on the rule of thumb thresholds as follows:-

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

34

Salome L. Munub, O. A. Kakumu & Winnie Mwangi

The mean of each variable under study totalled to 15/5 on a 5-point linkert scale. Therefore a value of >3.0

indicated satisfaction/adequacy while <3.0 was dissatisfaction/inadequacy (Kothari 2004, Somekh and Lewin

2009). In this case, a standard deviation (SD)>0.5 indicated a strong positive relationship with the alternative

hypothesis.

Bryman and Cramer (2001) and Israel (1992), provide the following rule of thumb for Cronbach Alpha where

a P value of >0.9 Excellent, >0.8 Good, >0.7 Acceptable, >0.6 Questionable, >0.5 Poor and <0.5

Unacceptable. Movement towards a P value of 0.00, indicates concurrence with the statement. Cronbach

Alpha as a coefficient of internal consistency indicates an acceptable value of 0.7 as a cutoff for reliability.

Pearsons Bivariate Correlation measures the relationship between two variables from +1 to -1; where +1 is a

strong positive correlation, -1 a strong negative correlation, and 0.0 is lack of relationship between the two

variables. The closer the correlation tends to zero the weaker the relationship.

Multiple Linear Regression analysis tested the influence of the predictor variables on the dependent variable

i.e. the fit between socio-cultural and economic attributes with just terms of compensation. A coefficient of

determination (R2) = or > 0.5 means the higher the coefficient, the stronger the relationship between the

variables.

6.0 DATA FINDINGS, PRESENTATION AND ANALYSES

The questionnaires were administered to 356 respondents against a population size of 672 PAPs. Table 4 below

indicated 210 respondents which was above 63%, thereby increasing reliability of the findings.

Table 4: Sample Size and Response Rate

Category

Sample size

Land Owners

221

SMEs

93

Institutions

30

Implementers

12

Total

356

Source: Field Study (2015)

500

Response

106

76

19

9

210

Percentage Response

86.89

81.72

63.33

75.00

58.98

Population, Sample Size and Response Rates in

the Four Categories

400

300

200

100

0

Land Owners Population SMEs

Sample Size

Institutions

Response Rate

Imlementers

Figure 4: The Population, Sample Size and Response Rate

Impact Factor (JCC): 3.0965

NAAS Rating: 3.63

Involuntary Resettlement Policy and Praxis in Kenya: An Evaluation of Just Terms of Compensation

35

6.1 Reliability of the Main Study Results

In the main study, reliability results for the four (4) categories on the 29 prompts attracted a Cronbach Alpha

statistic >0.7. A Cronbach Alpha of 0.7 indicates that the data collection instrument is reliable (Israel 1992). The reliability

statistics are presented in Table 5 below:Table 5: Reliability of the Main Study

Category

Households

Implementing/Poli

cy Makers

Institution

SMEs

Construct

Level of Awareness

Satisfaction with compensation

practices

Socio-economic practices

Level of awareness

Satisfaction with compensation

practices

Socio-economic practices

Level of awareness

Satisfaction with compensation

practices

Socio-economic practices

Level of awareness

Satisfaction with compensation

practices

Socio-economic practices

Number of

Statements

10

Cronbach

Alpha

0.953

Reliable

10

0.694

Reliable

9

10

0.685

0.817

Reliable

Reliable

10

0.821

Reliable

9

10

0.891

0.938

Reliable

Reliable

10

0.856

Reliable

9

10

0.939

0.895

Reliable

Reliable

10

0.841

Reliable

8

112

0.884

0.851

Reliable

Reliable

Overall

Source: Field study (2015)

Comment

6.3 Data Analyses Techniques

Three data analyses techniques were applied for data analyses.

Pearsons Bivariate Correlation

Bivariate correlation indicates the relationship between two variables. The correlation between satisfaction with

compensation praxis and level of awareness though positive, was weak (0.237) and significant (0.003). This meant that a

change in satisfaction with compensation praxis versus the level of awareness changed in the same direction. In addition,

the correlation between satisfaction with compensation and praxis inclusion of just compensation (social-cultural and

economic) factors in compensation was strongly positive (0.534) and significant. This showed that a change in satisfaction

with compensation praxis is positively correlated (0.534) with inclusion of social-cultural and economic factors as

indicated in Table 7 below.

Table 6: Pearsons Bivariate Correlation

Variable

Satisfaction with

compensation practices

Level of awareness

Socio-Economic Factors

www.tjprc.org

Satisfaction

Pearson Correlation

Sig. (2-tailed)

Pearson Correlation

Sig. (2-tailed)

Pearson Correlation

Sig. (2-tailed)

0.237

0.003

0.534

0.000

Level of

Awareness

Social-Economic

Factors

1

0.282

0.014

editor@tjprc.org

36

Salome L. Munub, O. A. Kakumu & Winnie Mwangi

Table 6: Contd.,

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Source: Field Study (2015)

Regression Analysis

Linear Regression Analysis tested the influence of predictor variables on dependent variables. The results in Table

8.0 below indicated the regression models best fit explained satisfaction with compensation praxis. This is supported by a

composite positive correlation of 0.618 and coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.382. Therefore, predictor variables

explained at least 38.2% of the variation in satisfaction with compensation praxis. The standard error of estimate (0.76459)

was negligible indicating a representative sample of the population on movement towards 1.0.

Table 7: Regression Fitness Model

Indicator

R

R2

Std. Error of the Estimate

Source: Field Study (2015)

Coefficient

0.618

0.382

0.76459

Regression output of the predictor variables indicated the level of awareness and inclusion of social-cultural and

economic factors as statistically significant factors influencing just compensation. The beta coefficient indicated the

direction and degree of influence of the predictor variable on the dependent variable. For example, a beta coefficient of

0.265 on level of awareness meant that a unit change in level of awareness caused a 0.265 positive unit change in

satisfaction with compensation. Results in Table 9.below indicated a strong relationship between satisfaction and inclusion

of socio-cultural and economic factors.

Table 8: Regression Coefficients

Variable

Constant

Level of awareness

Social economic factors

Source: Field Study (2015)

Beta

0.233

0.265

0.707

Std. Error

0.307

0.079

0.155

T

0.759

3.353

4.579

Sig.

0.450

0.001

0.000

Analysis of Variance Technique

The ANOVA technique compared responses to each question within each of the four categories under study. The

respective category sample means were then compared against the four categories mean. Sum of total variable means were

then broken into component parts using squared deviation of variances to compute deviation of each category first, from

their own mean and secondly from the grand mean i.e. within group variance and between group variances. Cross

tabulation collated unit characteristics among the variables.

According to Cooper and Schindler (2011), a probability (p) value < 0.05, is significant. If p-value is >0.7, it is

insignificant and the model is not suitable. In the study, the calculated F statistic was greater that the critical F statistic in

the F distribution table, meaning rejection of null hypothesis (Ho) (see Hinton et. al 2004; Kothari, 2008).

Impact Factor (JCC): 3.0965

NAAS Rating: 3.63

Involuntary Resettlement Policy and Praxis in Kenya: An Evaluation of Just Terms of Compensation

37

Table 9: ANOVA

Attributes

Sum of Squares

Between Groups

42.091

Within Groups

25.965

Total

68.055

Source: Field Study (2015)

Df

2

215

217

Mean Square

12.982

0.585

F

22.207

Sig. (p)

0.000

Table 6 above indicated ANOVA findings that the combined effect of the independent variables was significant in

explaining satisfaction with compensation practices with an F statistic of 22.207.

6.4 Satisfaction Gap in Just Compensation

The satisfaction gap addressed objective one using a 19 prompt questionnaire that established first, the adequacy

of the compensation praxis and secondly, the inclusion of socio-economic determinants of social disarticulation as follows.

To what extent:

Is it just for the Government to compulsory acquire your land?

Is it just to take possession of uncultivated, pasture or arable land out of urgency of the project before payment of

compensation?

Is the monetary compensation for acquired land just?

Is the compensation for developments on land just?

Is compensation paid for damage caused during survey just?

Is compensation paid for relocation of plant and machinery just?

Is compensation to relocate paid to the land owner promptly?

Is the legal redress mechanism determining claims of interests just?

Is the legal redress just in settlement of disputes on relocation?

Is it just for the court to determine who to pay litigation costs when seeking justice?

The questionnaire further established the inclusion of socio-cultural and economic issues in just compensation

focusing on Cernias (2000) eight-tier social disarticulation model. This established the extent of:

The acceptability to relocate from the land by other dependents.

The interests of family dependents in the compensation awards.

The law addressing the issue of landlessness.

The law addressing the issue of homelessness.

The law addressing the issue of joblessness.

The law addressing the issue of marginalization in host communities.

The law addressing the issue of food insecurity.

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

38

Salome L. Munub, O. A. Kakumu & Winnie Mwangi

The law addressing the issue of loss of access to common property resources.

The socio-cultural and economic issues in the compensation praxis.

Source: Field Study (2015)

Figure 5: Satisfaction Gap in Just Compensation

The results in Figure 5 above indicated that the average mean for Households (1.53), SMEs (1.912) and

Institutions (2.70) is below the acceptable mean level (3.0). This signified dissatisfaction with adequacy of compensation

by the three categories. Policy makers/implementers had a mean (3.36) above mean level>3.0 signifying marginal

satisfaction of 0.366 with the compensation praxis.

The SD analysis indicated Households (0.81), SMEs (1.34), Institutions (1.05) and Policy makers/implementers

(1.182), all being >0.5. These findings affirmed that inclusion of socio-cultural and economic variables reflecting just

compensation were not provided in praxis.

6.5 Level of Awareness of Compensation Praxis

Objective two of the study was established using a 10 prompt questionnaire on level of awareness of legal

framework on compulsory acquisition. To examine the level of awareness of the policy on:

The Constitution provisions for compulsory acquisition of land for public purposes

Publication of the parcels to be acquired in a gazette notice.

Payment of compensation resulting from compulsory acquisition.

Presentation of claims by persons with interest at a gazetted inquiry.

Statutory provisions on compensable attributes.

Legal framework for compensation under compulsory acquisition

Compensation to damage caused by survey

Severance in costing for relocation

Impact Factor (JCC): 3.0965

NAAS Rating: 3.63

Involuntary Resettlement Policy and Praxis in Kenya: An Evaluation of Just Terms of Compensation

Injurious affection in costing of relocation

Disturbance in costing for relocation

39

Source: Field Study (2015)

Figure 6: Level of Aware of Compensation Praxis

The results in Figure 6 above indicated the mean for Households (2.7) and SMEs (2.51) as below the average

mean of 3.0, meaning lack of awareness policy and compensation praxis. However, Institutions (3.4) and Policy

makers/implementers (4.37) were above the average mean of 3.0 indicating a general awareness, though, Institutions had a

marginal score of 0.4 above the mean.

The SD analysis indicated Households (1.71), SMEs (1.48), Institutions (1.5) and Policy makers/implementers

(0.7); affirming that being >0.5, the SD is reflective of the strong positive relationship between awareness and just

compensation.

7.0 SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS

Collation of the various data analyses techniques revealed that social disarticulation is ignored in compensation

praxis in involuntary resettlement. The regression co-efficient indicated a strong relationship between adequacy of

compensation and Cernias (2000) eight-tier social disarticulation model. Therefore, the HRBA principles and the UN 1948

Declaration represent the dependency rights foregone in involuntary resettlement.

The ANOVA technique established influence of predictor variables on dependent variables outside the policy

framework. The regression fitness model indicated that level of awareness and inclusion of social-cultural and economic

factors influenced just terms of compensation reflected by the beta coefficient of a positive movement in direction and

degree of both attributes. A reduction in satisfaction variables reduced the justness of compensation. The study deduced

that just terms of compensation are not provided in policy framework and compensation praxis, therefore the null (Ho)

hypothesis was rejected.

A review of the policy framework established confinement of compensation praxis within colonial policy

precincts that ignored salient socio-cultural tenets on justice within African social formations. World Bank guidelines

advocate for broader inclusion of customary familial composition thereby supporting the NLP, the Constitution and Land

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

40

Salome L. Munub, O. A. Kakumu & Winnie Mwangi

Act (GoK 2009, 2010, 2012a). Introduction of occupants in good faith without tittle, public rights of way and wayleaves,

has broadened the compensation arena, however, the existing legal frameworks continually ignore inclusion of sociocultural and economic tenets that ensure restoration of livelihoods to PDPS. Therefore, need for re-definition of just

compensation in involuntary resettlement policy, regulations, guide-lines and procedural manuals cannot be ignored.

In recommending a model for just terms of compensation in involuntary resettlement policy and praxis in Kenya,

Figure 7 below illustrates tangible variables in economic-valuation approaches provided in legal frameworks, sociologist

approaches on intangible socio-cultural and economic variables and a convergent mesh of the legal and social perspectives

as a bridging model for just terms of compensation.

Source: Author (Field Study 2015)

Figure 7: Conceptual Illustration of Attributes on Just Compensation

8.0 CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER AREAS OF STUDY

ANOVA analysis established that compensation praxis does not provide for socio-cultural and economic modules

of just terms of compensation concepts. This is because the legal and financial frameworks ignored the non-tangible,

secondary derivative interests on land. Furthermore, the displacement arena was exposed to non-uniform compensation

praxis within a non-responsive regulated framework, deviant to philosophies and concepts of justice. Resultant were the

land reforms that validated traditional familial tenets to mitigate the social disarticulation abysses.

Impact Factor (JCC): 3.0965

NAAS Rating: 3.63

Involuntary Resettlement Policy and Praxis in Kenya: An Evaluation of Just Terms of Compensation

41

Since the research focused on just terms of compensation of involuntary resettlement policy and praxis in Kenya:

The Case Study of Nairobi-Thika highway. It would interest socio-political students to formulate public policy for

involuntary resettlement in this period of land reforms. Since data analyses techniques established gaps between drivers of

just compensation and policy provisions, it would interest Valuers and Realtors to formulate policy instruments that

identify measure and comprehensively quantify compensation structures reflecting socio-cultured and economic variables

espoused in the NLP towards just terms of compensation. Such a hedonic valuation approach reaffirms equitable property

rights and access to land in just compensation praxis espoused in the Constitution of Kenya.

REFFERENCES

1.

Agbola T. and Jinadu A. M. (1997): Forced eviction and forced relocation in Nigeria: the experience of those evicted from

Maroko in 1990; Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 9, No. 2,

2.

Almond N. and Plimmer P. (1997): An investigation into the use of compulsory acquisitions by agreement; Property

Management Volume 15 Number 1 1997 pp. 3848; MCB University Press.

3.

Braun, Y. A. (2005) Resettlement and Risk: Women's Community Work in Lesotho; Advances in Gender Research Issue 9, pp.29

60; Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

4.

Bryman, A. and D. Cramer (2001) Quantitative Data Analysis with SPSS Release 10 for

5.

Windows: A guide for social scientists, Hove and New York: Routledge.

6.

Burrows, P. (1991): Compensation for Compulsory Acquisition; Land Economics, Vol. 67, No. 1 pp. 49-63: University of

Wisconsin Press. Available from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3146485(30/09/2011).

7.

Cernea M.M. (1999): Why Economic Analysis Is Essential to Resettlement: A Sociologist's View; Economic and Political

Weekly, Vol. 34, No. 31 (Jul. 31 - Aug. 6, 1999), pp. 2149-2158: Economic and Political Weekly; Available from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/4408255 (10/02/2012)

8.

Cernea M.M. (2000): Risks, Safeguards and Reconstruction: A Model for Population Displacement and Resettlement:

Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 35, No. 41 (Oct. 7-13, 2000), pp. 3659-3678: Economic and Political Weekly: available

from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4409836 (10/02/2012)

9.

Chan N. (2003): Land Acquisition Compensation In china- Problems and Answers: -International Real Estate Review Vol. 6.

No. 1 pp. 136-152: International Real Estate Review

10. Croll E. J. (1999): Involuntary Resettlement in Rural China: The Local View; The China Quarterly, No. 158 (Jun., 1999), pp.

468-483; Cambridge University Press; Available fromhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/656090 (10/02/2012).

11. De Wet C. (2001): Economic Development and Population Displacement: Can Everybody Win? Economic and Political

Weekly, Vol. 36, No. 50 (Dec. 15-21, 2001), pp. 4637-4646: Economic and Political Weekly Available from:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/4411475 (10/02/2012).

12. De Soto, H. (1994): The Missing Ingredient: What Poor Countries Will Need To Make Their Markets Work.Housing Finance

International.Available fromhttp://www.Housingfinance.org/uploads/publicationsmanager/9406 Dev. (7/01/2011)

13. Ding C. (2005): Policy and praxis of land acquisition in China, Land Use Policy Science Direct 24 (2007) pg 113; Elsevier

Ltd

14. Elman P. (1968): Compulsory Acquisition in Israel Law: The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 1

(Jan., 1968), pp. 215-221: Cambridge University Press

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

42

Salome L. Munub, O. A. Kakumu & Winnie Mwangi

15. Frank J (2002); Two Models of LandReform and Development InBrazil:Jeffrey Frank Z magazine-Third World Traveller

Available from www.thirdworldtraveler.com/.../Land_Reform_Brazil.html (10/2/2012)

16. Harbeson J. W.(1973); Nation building in Kenya; North Western University press

17. Hill M. F: (1976: Permanent Way; The Story Of Kenya and Uganda Railway; English Press

18. Israel, Glenn D. (1992): Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of

Florida. Reviewed June 2012.Available from http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu. (30/04/2013)

19. Janvry A and Sadoulet E. (2002): Land Reforms in Latin America: Ten Lessons toward a Contemporary Agenda; University of

California at Berkeley

20. Hydman R. (2008): Quantitative Business Research Methods; Wiley and Sons

21. Kalabamu F. T. (2000): Land tenure and management reforms in East and Southern Africa - the case of Botswana: Land Use

Policy 17 (2000) pp. 305-319, Pergamon.

22. Kothari S. (1996): Whose Nation? The PDPs as Victims of Development; Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 31, No. 24 (Jun

15, 1996), pp. 1476-1485 ; Economic and Political Weekly; Available from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4404269 (10/02/1012)

23. Lambais G. B. R (2008); Land Reform in Brazil: The Arrival of the Market Model; Economics Institute University of

Campinas

LLILAS

University

of

Texas

at

Austin.

Available

from

http:lanic.utexas.edu/project/etext/lilas/ilassa/2008/lambais.pdf (14/06/2012)

24. Lawrence D. M, Rees W. H, Britton W. (1976) modern Methods Of Valuation of land, Houses and Buildings (Sixth edition);

Pitman Press, Bath

25. Mangioni V. (2008): Just Terms Compensation And The Compulsory Acquisition Of Land;Pacific Rim Real Estate Society

Malaysia, pp. 1-13 Available from http://hdl.handle.net/10453/11287 (12/7/2012)

26. Mdlongwa F. (1998): Land Reforms Zimbabwe presses land distribution:AfricaRecoveryUnited Nations, Vol.12, page 10-15:

United

Nations

New

York

Mendie A., Atser J. and Ofem B. (2010): Analysis of Public Lands Acquisition in AkwaIbom State, Nigeria, Department of

Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Environmental Studies, University of Uyo, P. M.B. 1017, Uyo, Nigeria

27. Menezes A. (1991):Compensation for Project Displacement-A New Approach; Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 26, No. 43

(Oct. 26, 1991), pp. 2465-2469 ; Economic and Political Weekly; Available from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4398222

(30/09/2011)

28. Mugenda M. O and Mugenda G. A (2003): Research Methods Quantitative & Qualitative Approaches: Revised Edition. ACT

Press.

29. Ndegwa P. (1985): Africas Development Crisis and Related International Issues; Heinemann Educational Books

30. Neuman W. Lawrence (2011): Social Research Methods, Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches Pearson

31. Ngau P and Kumssa A. (2004): Research Design, Data Collection and Analysis: A training Manual; UNCRD textbook series

no. 12; United Nations Centre For Regional Development Africa Office

32. Ng'ong'ola C. (1992): The Post-Colonial Era in Relation to Land Expropriation Laws in Botswana, Malawi, Zambia and

Zimbabwe: The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 41, No. 1 pp. 117-136: Cambridge University Press on

behalf of the British Institute of International and Comparative Law Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/760787

(10/02/2012)

Impact Factor (JCC): 3.0965

NAAS Rating: 3.63

Involuntary Resettlement Policy and Praxis in Kenya: An Evaluation of Just Terms of Compensation

43

33. Nuhu M. B and Aliyu A. U (2009): Compulsory Acquisition of Communal Land and Compensation Issues: The Case of Minna

Metropolis - Nigeria

34. Obeng-Odoom F. (2012): Land reforms in Africa: Theory, practice, and outcome; Habitat International 36 ppg. 161-170

35. Okoth-Ogendo, H.W.O. (1991); Tenants of the Crown; Evolution of Agrarian law and Institutions in Kenya; African Centre for

Technology Studies

36. Republic of Kenya (1970): Trust Land Act Chapter 288; Government Printers.

37. Republic of Kenya (1990): Land Acquisition Act Cap 295(Repealed); Government Printers

38. Republic of Kenya (2010): The Constitution of Kenya: Government Printer Nairobi

39. Rwiza N. Richard (2010): Ethics of human rights, The African Contribution; Catholic University of East Africa Press.

40. Selltiz C.,Wrightsman L. S. and Cook S. W. (1976): Research Methods in social relations, Holt, Rinehart and Winston Inc.

41. Sorrenson M.P.S (1967); Land Reforms in Kikuyu Country: A Study of Government Policy, East African Review of Social

Research

42. Syagga P. M and Olima H.M. (1996): The Impact Of Compulsory Land Acquisition On PDPs Households: The case Of The

Third Nairobi Water Supply Project; Kenya; HABITAT INTL,Vol 20 No. 1 pp 61-76; Elsevier Science Ltd

43. Thomas K. J. A. (2002): Development projects and Involuntary Population Displacement: The worlds Banks Attempt to

correct Past Failures; Population Research and Policy Review, Vol 21 No. 4 pp. 339-349: Springer; Available from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40230792 (10/02/2012)

44. Umeh A. J (1973): Compulsory Acquisition of Land and compensation in Nigeria. London Sweet & Maxwell,

45. Westbrook R.W (1977): Valuers Case Book of Approved Valuations; Pitman Press.

46. Wilmsen B. (2011): Progress, problems, and prospects of dam-induced displacement and resettlement in China: Sage

47. Yahya S. Saad (1976); Urban Land Policy In Kenya: Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philososphy-University of Nairobi

Department of Real Estate Economics, Royal Institute of Technology Stockholm

48. Yin R. (2003): Application of case study research: Sage publications Inc.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

This article is excerpted from the doctoral thesis written by author SLM. The work was carried out in

collaboration between all the authors. Author SLM designed the study, gathered the initial data, performed preliminary data

analysis, wrote the protocol and the first draft of the manuscript. Author WM managed the literature searches while author

OAK performed the statistical analysis and managed the analyses of the study. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

www.tjprc.org

editor@tjprc.org

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Political Spectrum WorksheetDocument3 pagesPolitical Spectrum WorksheetDanaNo ratings yet

- MONEY Laundering and Hawala TransactionDocument22 pagesMONEY Laundering and Hawala Transactionsamad_bilgi3552100% (4)

- Chapter 3 Problems - FinmgtDocument11 pagesChapter 3 Problems - FinmgtLaisa Vinia TaypenNo ratings yet

- Ia - Valix2 Problem 20 - 4Document3 pagesIa - Valix2 Problem 20 - 4Parvana NamikazeNo ratings yet

- Volvo Truck - Penetrating The US MarketDocument5 pagesVolvo Truck - Penetrating The US MarketKha NguyenNo ratings yet

- Unilever Revenue CycleDocument14 pagesUnilever Revenue CycleShinta Risandi100% (4)

- LNG Contract StructureDocument31 pagesLNG Contract Structurevenancio-20100% (4)

- Baluchari As The Cultural Icon of West Bengal: Reminding The Glorious Heritage of IndiaDocument14 pagesBaluchari As The Cultural Icon of West Bengal: Reminding The Glorious Heritage of IndiaTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 29 1645708157 2ijtftjun20222Document8 pages2 29 1645708157 2ijtftjun20222TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Flame Retardant Textiles For Electric Arc Flash Hazards: A ReviewDocument18 pagesFlame Retardant Textiles For Electric Arc Flash Hazards: A ReviewTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 52 1649841354 2ijpslirjun20222Document12 pages2 52 1649841354 2ijpslirjun20222TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 4 1644229496 Ijrrdjun20221Document10 pages2 4 1644229496 Ijrrdjun20221TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study of Original Paithani & Duplicate Paithani: Shubha MahajanDocument8 pagesComparative Study of Original Paithani & Duplicate Paithani: Shubha MahajanTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Development and Assessment of Appropriate Safety Playground Apparel For School Age Children in Rivers StateDocument10 pagesDevelopment and Assessment of Appropriate Safety Playground Apparel For School Age Children in Rivers StateTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Covid-19: The Indian Healthcare Perspective: Meghna Mishra, Dr. Mamta Bansal & Mandeep NarangDocument8 pagesCovid-19: The Indian Healthcare Perspective: Meghna Mishra, Dr. Mamta Bansal & Mandeep NarangTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 33 1641272961 1ijsmmrdjun20221Document16 pages2 33 1641272961 1ijsmmrdjun20221TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 51 1651909513 9ijmpsjun202209Document8 pages2 51 1651909513 9ijmpsjun202209TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Dr. Gollavilli Sirisha, Dr. M. Rajani Cartor & Dr. V. Venkata RamaiahDocument12 pagesDr. Gollavilli Sirisha, Dr. M. Rajani Cartor & Dr. V. Venkata RamaiahTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 51 1656420123 1ijmpsdec20221Document4 pages2 51 1656420123 1ijmpsdec20221TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 44 1653632649 1ijprjun20221Document20 pages2 44 1653632649 1ijprjun20221TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Using Nanoclay To Manufacture Engineered Wood Products-A ReviewDocument14 pagesUsing Nanoclay To Manufacture Engineered Wood Products-A ReviewTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Vitamin D & Osteocalcin Levels in Children With Type 1 DM in Thi - Qar Province South of Iraq 2019Document16 pagesVitamin D & Osteocalcin Levels in Children With Type 1 DM in Thi - Qar Province South of Iraq 2019TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Reflexology On Post-Operative Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesEffectiveness of Reflexology On Post-Operative Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic ReviewTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- A Review of "Swarna Tantram"-A Textbook On Alchemy (Lohavedha)Document8 pagesA Review of "Swarna Tantram"-A Textbook On Alchemy (Lohavedha)TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- An Observational Study On-Management of Anemia in CKD Using Erythropoietin AlphaDocument10 pagesAn Observational Study On-Management of Anemia in CKD Using Erythropoietin AlphaTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Effect of Degassing Pressure Casting On Hardness, Density and Tear Strength of Silicone Rubber RTV 497 and RTV 00A With 30% Talc ReinforcementDocument8 pagesEffect of Degassing Pressure Casting On Hardness, Density and Tear Strength of Silicone Rubber RTV 497 and RTV 00A With 30% Talc ReinforcementTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Self-Medication Prevalence and Related Factors Among Baccalaureate Nursing StudentsDocument8 pagesSelf-Medication Prevalence and Related Factors Among Baccalaureate Nursing StudentsTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Numerical Analysis of Intricate Aluminium Tube Al6061T4 Thickness Variation at Different Friction Coefficient and Internal Pressures During BendingDocument18 pagesNumerical Analysis of Intricate Aluminium Tube Al6061T4 Thickness Variation at Different Friction Coefficient and Internal Pressures During BendingTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 51 1647598330 5ijmpsjun202205Document10 pages2 51 1647598330 5ijmpsjun202205TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 67 1640070534 2ijmperdfeb202202Document14 pages2 67 1640070534 2ijmperdfeb202202TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 67 1645871199 9ijmperdfeb202209Document8 pages2 67 1645871199 9ijmperdfeb202209TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 67 1644220454 Ijmperdfeb202206Document9 pages2 67 1644220454 Ijmperdfeb202206TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Comparative Fe Analysis of Automotive Leaf Spring Using Composite MaterialsDocument22 pagesComparative Fe Analysis of Automotive Leaf Spring Using Composite MaterialsTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Bolted-Flange Joint Using Finite Element MethodDocument12 pagesAnalysis of Bolted-Flange Joint Using Finite Element MethodTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 67 1653022679 1ijmperdjun202201Document12 pages2 67 1653022679 1ijmperdjun202201TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- 2 67 1641277669 4ijmperdfeb202204Document10 pages2 67 1641277669 4ijmperdfeb202204TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Next Generation'S Energy and Time Efficient Novel Pressure CookerDocument16 pagesNext Generation'S Energy and Time Efficient Novel Pressure CookerTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Basic Accounting SystemDocument37 pagesBasic Accounting SystemGetie TigetNo ratings yet

- Question Bank With Answers: Module-1Document52 pagesQuestion Bank With Answers: Module-1kkvNo ratings yet

- Wright v. Owens Corning, 679 F.3d 101, 3rd Cir. (2012)Document18 pagesWright v. Owens Corning, 679 F.3d 101, 3rd Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Kurikulum S1 Finance & Banking Peminatan BankingDocument6 pagesKurikulum S1 Finance & Banking Peminatan BankingIka Yunsita PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Abandono de PozosDocument60 pagesAbandono de PozosIvan Reyes100% (1)

- Caf 8 Cma Autumn 2015Document4 pagesCaf 8 Cma Autumn 2015mary50% (2)

- Updated Catalogue - Blore LA 27.09.19Document12 pagesUpdated Catalogue - Blore LA 27.09.19Rajeshwari MgNo ratings yet

- Chap 015Document19 pagesChap 015RechelleNo ratings yet

- Fringe Benefit FSLGDocument92 pagesFringe Benefit FSLGkashfrNo ratings yet

- Best of LUCK ..!Document1 pageBest of LUCK ..!Wajid HussainNo ratings yet

- Culinary Union Letter To Gaming Control Board Re: Alex MerueloDocument5 pagesCulinary Union Letter To Gaming Control Board Re: Alex MerueloMegan MesserlyNo ratings yet

- Ruma GhoshDocument26 pagesRuma GhoshhritamgemsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 PDFDocument22 pagesChapter 8 PDFJay BrockNo ratings yet

- ??eventi Swig 2019 @india?? PDFDocument2 pages??eventi Swig 2019 @india?? PDFjinefretNo ratings yet

- IFS Module 2Document47 pagesIFS Module 2Dhrumi PatelNo ratings yet

- Capital Investments and FCFDocument21 pagesCapital Investments and FCFMMNo ratings yet

- IIBF Annual Report 2018-19 PDFDocument111 pagesIIBF Annual Report 2018-19 PDFanantNo ratings yet

- Cnooc LimitedDocument3 pagesCnooc LimitedMahdiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Audit of The Revenue Cycle: Auditing, 14e (Arens)Document47 pagesChapter 12 Audit of The Revenue Cycle: Auditing, 14e (Arens)yen claveNo ratings yet

- Cambridge IGCSE™: Business Studies 0450/12 March 2021Document24 pagesCambridge IGCSE™: Business Studies 0450/12 March 2021Wilfred BryanNo ratings yet

- Thapa. Bina Thapa. Prakash PDFDocument76 pagesThapa. Bina Thapa. Prakash PDFTILAHUNNo ratings yet

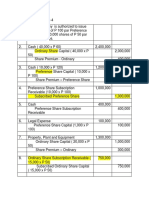

- Projected Cash Income For The Year 2021-2025 RevenuesDocument9 pagesProjected Cash Income For The Year 2021-2025 RevenuesAllia AntalanNo ratings yet