Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Acute Traumatic Posterior Shoulder Dislocation PDF

Uploaded by

Muhammad Pringgo ArifiantoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Acute Traumatic Posterior Shoulder Dislocation PDF

Uploaded by

Muhammad Pringgo ArifiantoCopyright:

Available Formats

Review Article

Acute Traumatic Posterior

Shoulder Dislocation

Abstract

Dominique M. Rouleau, MD

Jonah Hebert-Davies, MD

C. Michael Robinson, MD

From the Department of Orthopaedic

Surgery, University of Montreal,

Sacred Heart Hospital of Montreal,

Montreal, ON, Canada (Dr. Rouleau

and Dr. Hebert-Davies), and the Royal

Infirmary of Edinburgh, Edinburgh,

UK (Dr. Robinson).

Dr. Rouleau or an immediate family

member is a member of a speakers

bureau or has made paid presentations

on behalf of Smith & Nephew; has

received research or institutional

support from DePuy, KCI, Smith &

Nephew, Stryker, Synthes, and

Zimmer; and has received nonincome

support (such as equipment or

services), commercially derived

honoraria, or other nonresearchrelated funding (such as paid travel)

from Arthrex. Dr. Robinson or an

immediate family member is a member

of a speakers bureau or has made

paid presentations on behalf of and

serves as a paid consultant to Acumed.

Neither Dr. Hebert-Davies nor any

immediate family member has received

anything of value from or has stock or

stock options held in a commercial

company or institution related directly

or indirectly to the subject of this article.

J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2014;22:

145-152

http://dx.doi.org/10.5435/

JAAOS-22-03-145

Copyright 2014 by the American

Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

March 2014, Vol 22, No 3

Posterior shoulder dislocation occurs rarely and is challenging to

manage. The mechanisms of trauma are varied, which complicates

diagnosis. Missed or delayed diagnosis and treatment can have

serious deleterious effects on shoulder function. All cases of

suspected posterior shoulder dislocation require a high level of

suspicion and appropriate imaging. Identification of associated

injuries, such as fractures and rotator cuff tears, is important to guide

treatment. In the acute setting, most patients are treated with closed or

open reduction with additional soft-tissue or bony procedures.

Patients treated in a delayed fashion for persistent instability may

require additional procedures, including arthroplasty.

irst described in 1838 by Sir Astley

Cooper,1 traumatic posterior

dislocations of the shoulder represent

an unusual and challenging clinical

problem. These injuries account for

2% to 5% of all shoulder dislocations.1-3 Anterior glenohumeral

dislocation is 15.5 to 21.7 times more

common than posterior dislocation.4

Seizures, high-energy trauma, and

electrocution are associated with

a much greater risk of posterior

dislocation.1,2,5 Diagnosis is missed

or delayed in up to 79% of patients.2,3,6 The authors of one study

suggested that systematic evaluation

of AP and Velpeau radiographs in an

emergency department resulted in

dislocation being missed in only 10

of 112 patients.4

In patients who present following

seizure, electric shock, or trauma,

a high index of suspicion for posterior

shoulder dislocation should be maintained, and appropriate physical and

radiologic examinations should be

performed to confirm the diagnosis.7

This is particularly important in the

setting of seizure, in which medical

treatment combined with reduced

nociceptive sensitivity following

convulsions may make it difficult

for the treating physician to detect

the injury.8 Early identification of

these dislocations reduces morbidity

and facilitates treatment.3

Anatomy of the Shoulder

The shoulder is relatively unconstrained, allowing an extreme range

of motion. Joint stability is provided

by both static and dynamic elements,9 which allows the joint to

maintain a large degree of freedom

while remaining concentric.

Static Stabilizers

Bony congruity is achieved with the

concavity of the glenoid; this is further

increased due to asymmetric deposition

of cartilage, with the peripheral articular surface being thickest.10,11 The glenoid labrum increases the depth and

width of the joint approximately twofold.12 Loss of the labrum decreases

translational resistance by 20%.13

The three glenohumeral ligaments

are discrete capsular fibrous bands

145

Copyright the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Acute Traumatic Posterior Shoulder Dislocation

pectoralis and latissimus dorsi muscles

overpower the weak external rotators

(ie, infraspinatus, teres minor) and

cause internal rotation of the shoulder,

displacing the humeral head superiorly

and posteriorly against the acromion

and medially against the glenoid fossa,

resulting in posterior dislocation.8,16

Adequate muscle contraction strength

of the infraspinatus and teres minor

and major can cause humeral neck

fracture. In a recent systematic review,

posterior dislocations were found to

occur after trauma in 67% of cases,

after seizure in 31%, and after electrocution in 2%.4

Figure 1

Classifications

Illustration of the dynamic and static stabilizers of the shoulder. IGHL = inferior

glenohumeral ligament, MGHL = middle glenohumeral ligament, SGHL = superior

glenohumeral ligament

that provide stability to the shoulder in

various positions. The coracohumeral

ligament and superior glenohumeral

ligament provide little anterior resistance, but they help prevent posterior

translation in the flexed, adducted,

and internally rotated shoulder.12,14

The inferior glenohumeral ligament

is the main stabilizer against posterior

dislocation. The posterior band of

the inferior glenohumeral ligament

restricts posterior displacement with

the arm in abduction12 (Figure 1).

Dynamic Restraints

Dynamic stabilizers include all shoulder muscles that create a concavity

compression force across the joint.

Balance between anterior and posterior forces allows the humeral head

to remain centered in the glenoid.9

146

Posterior dynamic restraints of the

shoulder include the rotator cuff, the

biceps tendon, and the deltoid.12 The

subscapularis provides the greatest

opposition to posterior translation.12

The biceps tendon increases posterior

stability, mostly in external rotation.

Mechanisms of Injury

Several different mechanisms have

been proposed for posterior dislocation. Direct high-energy trauma with

the shoulder in adduction, flexion, and

internal rotation is the most frequent

cause of posterior dislocation.2,15

Posterior shoulder dislocation may

also be caused by seizures or electrocution.8 Dislocation due to seizure is

the result of unbalanced contraction of

the shoulder muscles.16 In adduction,

internal rotation, and flexion, the

Several classification systems exist to

describe posterior shoulder dislocations, but none has been established

as a clear standard. Detenbeck17 first

separated dislocations based on type:

acute, chronic (dislocated .3 weeks),

or recurrent (traumatic or atraumatic).

Heller et al18 developed a system

based on an extensive literature review

and included different parameters:

traumatic or atraumatic, acute or

persistent, or recurrent voluntary.

Others have classified dislocations as

acute (,6 weeks) or chronic (.6

months) and have separated pure

dislocations from fracture-dislocations

(ie, any associated humeral fracture

except a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion).19

Robinson and Aderinto19 also classified humeral head defect as small

(,25%), medium (25% to 50%),

and large (.50%). Classification of

the humeral head defect is extremely

important for planning eventual surgical treatment. Classifications of

posterior recurrent instability and

atraumatic posterior instability are

beyond the scope of this article.20

Clinical Evaluation

Physical examination is particularly

important in acute posterior shoulder

Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Copyright the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Dominique M. Rouleau, MD, et al

Figure 2

A, AP radiograph of the shoulder with the trough line visible (arrow). This is representative of the anterior humeral head

impaction. B, Axillary radiograph demonstrating posterior dislocation with a significant reverse Hill-Sachs lesion. C, AP

radiograph demonstrating the lightbulb sign (arrows).

dislocations because patients may be

unable to provide an adequate clinical

history. On visual inspection, the

shoulder often is in internal rotation,

with a prominent coracoid process and

posterior fullness in the axilla.1,3,21

Physical examination may reveal

a springy or soft end point or a block

to external rotation,1-3,21,22 as well as

the subtler sign of diminished supination of the forearm.6 Specific instability examinations such as the jerk test,

posterior load-and-shift test, or the

posterior drawer test can be useful

in patients with chronic instability.

However, these tests are rarely useful

in the acute setting.

Imaging

To minimize the risk of missing a posterior glenohumeral dislocation, the

evaluation should include standard

AP and Velpeau radiographs.1-4,21 An

axillary view is useful to evaluate

associated head impaction (ie, reverse

Hill-Sachs lesion) and glenoid rim

fractures.21 A Velpeau view is

acceptable if the patient is unable to

achieve sufficient abduction. Other

indirect signs that can be seen on

standard radiographs include the

lightbulb sign, loss of the half-moon

sign, and the trough line23 (Figure 2).

March 2014, Vol 22, No 3

CT is particularly useful for

preoperative assessment of associated fractures and quantification

of reverse Hill-Sachs impaction1,3,21,24,25 (Figure 3). Thin-slice

axial CT is the best imaging

modality for defining the humeral

head bone defect as part of the

articular surface.24

Capsulolabral and rotator cuff evaluation on MRI is essential in cases

without associated fracture7 (Figure 4).

Posterior labral lesions, such as reverse

Bankart lesions, posterior labrocapsular periosteal sleeve avulsions, and

posterosuperior tears, are found in up

to 58% of patients.26 In cases of

irreducible dislocation, MRI can

identify the responsible structure,

which most commonly is a torn rotator cuff, avulsed capsule, or biceps

tendon.26

Associated Injuries

Isolated posterior dislocations of the

proximal humerus are rare, and associated injuries often are missed or

diagnosed in a delayed fashion.7 Historically, bony and soft-tissue injuries

were thought to occur in 49% of

dislocations,21 but a recent systematic

review indicated that up to 65% of

dislocations had associated bony or

Figure 3

Axial CT scan demonstrating severe

humeral head impaction, that is,

reverse Hill-Sachs lesion. The extent

of glenoid fracture or bone loss

dictates management.

soft-tissue injuries.7 Simple or multiple

fractures were present in 34% of

shoulders, with the most common site

being the neck (55%), followed by

the lesser (42%) and greater (23%)

tuberosities.7 Lesser tuberosity fractures are particularly important

because they influence treatment. In

these cases, it is important to enter the

joint through the fracture rather than

perform a subscapularis tenotomy.

Reverse Hill-Sachs lesions of

varying size are seen in up to 86% of

147

Copyright the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Acute Traumatic Posterior Shoulder Dislocation

Figure 4

Axial T1-weighted magnetic

resonance arthrogram of a right

shoulder demonstrating a posterior

Bankart lesion. The rotator cuff is

also assessed on this view.

patients.26 Bone defects are common, with significant reverse HillSachs lesions found in 29% of

shoulders7 and posterior rim fracture seen in approximately 5% of

shoulders.4 The frequency and significance of these defects can

increase with delayed or chronic

presentation.5

Rotator cuff tears are found in 13%

of patients evaluated with MRI;

however, the odds ratio of finding

a tear is 4.6 times higher in the

absence of an associated fracture or

reverse Hill-Sachs lesion.7 Thus, in

the patient with a dislocation but

without concomitant fracture on

CT, a focused rotator cuff physical

examination and MRI evaluation

are strongly suggested. Nerve palsy

secondary to posterior glenohumeral

dislocation is rare, occurring in ,1%

of injuries.7 The axillary nerve is the

most commonly injured.

Management

Nonsurgical

Definitive treatment options for posterior shoulder dislocations are varied,

and the decision must be individualized to each patient. In the elderly

148

low-demand patient, chronic posterior dislocation can be tolerated provided pain is minimal and anterior

elevation is sufficient for activities

of daily living.27,28 This treatment

option has been dubbed supervised

neglect.28,29 Nonsurgical treatment

also may be appropriate in patients

with cognitive impairment or other

severe medical comorbidities.

Closed reduction can be attempted

in the presence of an acute dislocation

in an elderly low-demand patient

with a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion measuring ,20%. Recurrent dislocation

or failed reduction warrants a discussion with the patient and family

about definitive treatment. In an

active and independent patient, the

goal of treatment of acute and

chronic dislocations is to restore

shoulder stability and mobility. Isolated closed reduction is reserved for

acute posterior instability with

a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion of #20%

that is stable after reduction.

Careful imaging evaluation should

be done prior to any reduction

maneuver to avoid displacing a neck

fracture. In the presence of suspected

fracture, an urgent CT scan should be

obtained before reduction. An attempt

at closed reduction of posterior shoulder dislocation requires complete

sedation to allow gentle manipulation.

Forceful manipulations often cause

humeral head fractures, which increases the chance of osteonecrosis and

has an adverse effect on prognosis. In

a series of 112 patients, 33% of

shoulders were successfully reduced

using in-line gentle traction.4

The Stimson technique is a passive

method used to manage acute posterior dislocation without associated

neck fracture or a significantly engaged

reverse Hill-Sachs lesion. The patient is

positioned prone on a table with the

arm in abduction over the side and

with 5 to 10 lb placed in the hand.30

Muscle spasms can eventually be

overcome with the weight to allow for

spontaneous reduction.

Another method of closed reduction involves manipulating the

shoulder into adduction, anterior

flexion, and internal rotation. This is

followed by longitudinal traction

and anteriorly directed pressure on

the humeral head. As the humeral

head is felt to translate anteriorly,

progressive external rotation and

extension is done. Caution is required

at this stage because initiating rotation before humeral head translation

may cause humeral head fracture.

Residual instability following closed

reduction with the arm in the neutral

position warrants surgical management provided the patient is medically

fit to undergo anesthesia.

Surgical

Open Reduction

Following unsuccessful closed reduction, open reduction can be done

through either an anterior or a posterior approach. The approach is determined based on preoperative planning.

Isolated open reduction can be successful in acute dislocations with

reverse Hill-Sachs lesions measuring

,20%.

An anterior approach is done via

a standard deltopectoral incision,

where the humeral head lies deeper than

usual. Initially, the rotator interval is

opened to allow the introduction of

a finger into the glenohumeral joint to

aid in manual reduction of the shoulder.

In cases in which the shoulder is not

reducible through an open rotator

interval alone, a formal arthrotomy is

necessary. Management of the subscapularis is crucial and is dictated by

associated fractures. The two options

are peeling of the subscapularis and

lesser tuberosity osteotomy. In the setting of persistent posterior dislocation,

locked internal rotation limits access to

the subscapularis. The long head of the

biceps is useful in identifying the lateral

margin; frequently, the subscapularis

tendon lies beneath the conjoined

tendon.

Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Copyright the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Dominique M. Rouleau, MD, et al

mended to prevent contact between

the grafted zone and the glenoid.

Figure 5

formed approximately 1 cm deep to

the bicipital groove in the sagittal

plane. A second cut is made from the

rotator interval in the coronal plane

from the reverse Hill-Sachs lesion

medially to the groove laterally. This

cut is possible only if the rotator

interval is open. Careful manipulation

of the lesser tuberosity is required to

prevent fragmentation.

Posterior Open Bankart Procedure

Irreducible posterior shoulder dislocations or persistent instability after

closed reduction without a significant

reverse Hill-Sachs lesion (#20%) can

be managed with a posterior approach

to achieve reduction, followed by

posterior Bankart repair33 (Figure 7).

A posterior longitudinal incision is

made medial to the deltoid border in

line with the posterior joint. Inferior

dissection must be done carefully to

prevent injury to the axillary nerve.

The deltoid is lifted with a retractor,

after which the infraspinatus is visualized and transverse tenotomy is

performed in line with the capsule.

The posterior labrum and capsule are

repaired in a standard fashion. Alternatively, the approach can be done

through a longitudinal split between

the infraspinatus and teres minor. This

approach allows excellent exposure

of the labrum complex without posterior tendon tenotomy. The interval

between these muscles is not always

obvious. Typically, it can be found

2 cm inferior to the scapular spine. It is

harder to see the separation at the

tendinous portion, and a longitudinal

tenotomy is usually necessary. Alternatively, on palpation, the humeral

head is usually felt deep to the infraspinatus, whereas the inferior portion

of the teres minor feels soft on

palpation.

Anterior Approach and Bone

Grafting

Significant acute reverse Hill-Sachs

lesions (20% to 40%) can also be addressed with disimpaction and bone

grafting or allograft (Figure 6). The

ideal patient for these techniques is

young, with good healing potential.

Following fracture disimpaction, an

iliac crest bone graft can be inserted

under the cartilage for support.32

Postoperative use of an external

rotation splint for 4 weeks is recom-

Arthroscopic Posterior Bankart

Repair

Arthroscopic posterior Bankart repair

is an option for acute reducible dislocations with little or no humeral head

impaction (,20%) and with persistent instability. The arthroscope is

introduced through the anterior portal, and a posterolateral portal is used

for suture anchor placement. A posterosuperior portal is used for suture

management. The posterior portion of

the acromion may prevent vertical

A, Axial (top) and AP (bottom) illustrations of a shoulder with a reverse Hill-Sachs

lesion. The AP view illustrates a modified McLaughlin procedure, which is done

through a transsubscapularis approach. B, Axial (top) and AP (bottom)

illustrations of the shoulder following suture of the subscapularis tendon into the

defect with the help of suture anchors and subsequent repair of that approach

through the tendon.

The McLaughlin Procedure

For patients with reverse Hill-Sachs

lesions of #20% and with persistent

instability following reduction, the

subscapularis can be either lifted off

the lesser tuberosity and transposed

into the defect with transosseous sutures after reduction as originally

described by McLaughlin2 or sutured

into the bed of the defect.31 The circumflex vessels are preserved inferiorly by maintaining a small sleeve of

tendon attached to its original site.

Modified McLaughlin Procedure

In the presence of a significant reverse

Hill-Sachs lesion (20% to 40%), the

lesser tuberosity can be osteotomized

to access the joint and eventually

transposed to the bone defect after

joint reduction.21 This is known as

the modified McLaughlin procedure

(Figure 5). The osteotomy is perMarch 2014, Vol 22, No 3

149

Copyright the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Acute Traumatic Posterior Shoulder Dislocation

Figure 6

A, Axial CT scan of a left shoulder with significant humeral head impaction. B, Axial CT scan of the same patient 3 months

after an allograft was implanted into the deficit. C, Axial CT scan of a different patient with a similar injury 3 months after

fracture disimpaction.

Figure 7

Illustration of the skin landmarks

used in the posterior approach

(represented by the dashed line)

used to manage irreducible posterior

shoulder dislocation or persistent

instability after closed reduction in

the absence of a significant reverse

Hill-Sachs lesion. Access to the joint

is achieved either through

infraspinatus tenotomy or between

the infraspinatus and the teres minor.

positioning of suture anchors, and the

surgeon must have at the ready

a variety of suture passers to accommodate the anatomy in this area.

Arthroplasty

In the presence of massive humeral head

impaction (.40%) in patients aged

150

,55 years or in patients who are

not good candidates for graft incorporation, hemiarthroplasty is a good

option to address both instability

and the articular surface deficit.33

In order to prevent postoperative

dislocation, the humeral head must

be positioned in normal retroversion (#20). In more severe cases

of residual instability, the posterior

labrum can be repaired before

prosthesis implantation. Through

an anterior approach, the humeral

head is excised and the humeral cut

is oriented parallel to the glenoid,

leaving 1 to 2 cm of joint space to

visualize the posterior labrum. Use

of a laminar spreader and gentle

lateral traction can improve visualization. In a right shoulder, the

first glenoid anchor is positioned at

the 7-oclock position and the second at the 9-oclock position.

The anchor is placed at the edge of

the cartilage at a 45 angle to the

joint surface. A free 2/3 circular

needle is usually sufficient to pass

the anchor suture through the posterior labrum and capsule. Following repair of the labrum, the

hemiarthroplasty can be performed

as usual. A treatment algorithm is

shown in Figure 8.

Rehabilitation

Regardless of management type, the

shoulder is braced in 20 of external

rotation and abduction for 4 weeks to

aid healing of the posterior capsule.

Pendulum exercises and elbow range

of motion three times per day are

encouraged. At 4 weeks, unlimited

progressive range of motion is initiated

as well as isometric posterior rotator

cuff strengthening. Noncontact sports

are allowed 3 months after reduction or

surgery, and contact sports are permitted 4 to 6 months postoperatively.

Results

Approximately 18% of patients experience recurrent instability in the first

year following acute posterior dislocation.4 Risk factors for recurrence are

age ,40 years, seizure, and large

reverse Hill-Sachs lesion (.1.5 cm3).

Persistent functional impairment has

been noted 2 years after the initial

trauma, even without recurrent instability.4 Activities that require significant internal rotation may be

particularly difficult.

Typically, patients with persistent symptoms present with either

Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Copyright the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Dominique M. Rouleau, MD, et al

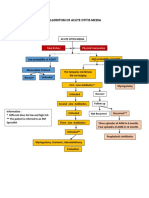

Figure 8

Treatment algorithm for the surgical management of acute posterior shoulder dislocation.

subjective or objective posterior

instability and a painful shoulder.

On physical examination, apprehension is seen with the shoulder in

adduction and forward elevation.

Most patients will present additional

symptoms with a posteriorly directed

translational force of the humerus.

Compensatory scapular winging can

be seen with anterior shoulder elevation.9 For these patients, imaging

should include magnetic resonance

arthrography of the shoulder. Treatments include all modalities of nonsurgical treatment as well as surgical

management of refractory cases. PosMarch 2014, Vol 22, No 3

terior capsular plication and posterior

Bankart repair have been reported to

improve both function and pain.34

Summary

Posterior shoulder dislocation is a relatively uncommon pathology, with

several typical modes of presentation.

Dislocation often goes undiagnosed in

the acute setting in patients who present following seizure, electric shock, or

high-energy trauma. Thus, particular

attention is required to diagnose the

injury in these patients. Imaging stud-

ies should always include an axillary

or equivalent radiograph. CT and

MRI are both useful to diagnose

associated injuries, which are much

more frequent than previously

thought. Treatment is individualized

to each patient based on timing

of presentation, size of the reverse

Hill-Sachs lesion, and the presence of

associated injuries (ie, fracture, rotator

cuff tear, glenoid bone loss). Younger

patients are treated with soft-tissue

management with or without a bony

procedure, whereas older patients

may require arthroplasty to maintain

stability.

151

Copyright the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Acute Traumatic Posterior Shoulder Dislocation

References

Evidence-based Medicine: Levels of

evidence are described in the table of

contents. In this article, reference 4 is

a level II study. Reference 7 is a level

III study. References 2, 3, 6, 8, 15,

16, 21, 22, 24, 26, 27, 29, and 31 are

level IV studies. Reference 28 is level

V expert opinion.

References printed in bold type are

those published within the past 5

years.

1. Kowalsky MS, Levine WN: Traumatic

posterior glenohumeral dislocation:

Classification, pathoanatomy, diagnosis,

and treatment. Orthop Clin North Am

2008;39(4):519-533, viii.

2. McLaughlin HL: Posterior dislocation of the

shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1952;24(3):

584-590.

3. Hatzis N, Kaar TK, Wirth MA,

Rockwood CA Jr: The often overlooked

posterior dislocation of the shoulder. Tex

Med 2001;97(11):62-67.

4. Robinson CM, Seah M, Akhtar MA: The

epidemiology, risk of recurrence, and

functional outcome after an acute traumatic

posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone

Joint Surg Am 2011;93(17):1605-1613.

5. Hawkins RJ: Unrecognized dislocations of

the shoulder. Instr Course Lect 1985;34:

258-263.

6. Rowe CR, Zarins B: Chronic unreduced

dislocations of the shoulder. J Bone Joint

Surg Am 1982;64(4):494-505.

7. Rouleau DM, Hebert-Davies J: Incidence of

associated injury in posterior shoulder

dislocation: Systematic review of the literature.

J Orthop Trauma 2012;26(4):246-251.

8. Goudie EB, Murray IR, Robinson CM:

Instability of the shoulder following

seizures. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012;94(6):

721-728.

9. Tjoumakaris FP, Bradley JP: Posterior shoulder

instability, in Galatz LM, ed: Orthopaedic

Knowledge Update: Shoulder and Elbow 3.

Rosemont, IL, American Academy of

Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2008, pp 313-320.

152

10. Matsen FA III: Letter: The biomechanics of

glenohumeral stability. J Bone Joint Surg

Am 2002;84(3):495-496.

11. Halder AM, Kuhl SG, Zobitz ME, Larson D,

An KN: Effects of the glenoid labrum and

glenohumeral abduction on stability of the

shoulder joint through concavitycompression: An in vitro study. J Bone Joint

Surg Am 2001;83(7):1062-1069.

12. Levine WN, Flatow EL: The

pathophysiology of shoulder instability.

Am J Sports Med 2000;28(6):910-917.

13. Lippitt S, Matsen F: Mechanisms of

glenohumeral joint stability. Clin Orthop

Relat Res 1993;(291):20-28.

14. Curl LA, Warren RF: Glenohumeral joint

stability: Selective cutting studies on the

static capsular restraints. Clin Orthop Relat

Res 1996;(330):54-65.

15. Robinson CM, Akhtar A, Mitchell M,

Beavis C: Complex posterior fracturedislocation of the shoulder: Epidemiology,

injury patterns, and results of operative

treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89(7):

1454-1466.

16. Shaw JL: Bilateral posterior fracturedislocation of the shoulder and other trauma

caused by convulsive seizures. J Bone Joint

Surg Am 1971;53(7):1437-1440.

17. Detenbeck LC: Posterior dislocations of the

shoulder. J Trauma 1972;12(3):183-192.

18. Heller KD, Forst J, Forst R, Cohen B:

Posterior dislocation of the shoulder:

Recommendations for a classification. Arch

Orthop Trauma Surg 1994;113(4):228-231.

19. Robinson CM, Aderinto J: Posterior

shoulder dislocations and fracturedislocations. J Bone Joint Surg Am

2005;87(3):639-650.

20. Millett PJ, Clavert P, Hatch GF III, Warner JJ:

Recurrent posterior shoulder instability. J Am

Acad Orthop Surg 2006;14(8):464-476.

21. Hawkins RJ, Neer CS II, Pianta RM,

Mendoza FX: Locked posterior dislocation

of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1987;

69(1):9-18.

22. Walch G, Boileau P, Martin B, Dejour H:

Unreduced posterior luxations and fracturesluxations of the shoulder: Apropos of 30

cases [French]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice

Appar Mot 1990;76(8):546-558.

23. Cisternino SJ, Rogers LF, Stufflebam BC,

Kruglik GD: The trough line: A

radiographic sign of posterior shoulder

dislocation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1978;

130(5):951-954.

24. Wadlington VR, Hendrix RW, Rogers LF:

Computed tomography of posterior

fracture-dislocations of the shoulder: Case

reports. J Trauma 1992;32(1):113-115.

25. Zissin R, Morag B, Apter S, Rubinstein Z:

Bilateral posterior glenohumeral fracturedislocation: CT appearance. Isr J Med Sci

1990;26(1):55-57.

26. Saupe N, White LM, Bleakney R, et al:

Acute traumatic posterior shoulder

dislocation: MR findings. Radiology 2008;

248(1):185-193.

27. Loebenberg MI, Cuomo F: The treatment

of chronic anterior and posterior

dislocations of the glenohumeral joint and

associated articular surface defects. Orthop

Clin North Am 2000;31(1):23-34.

28. Cicak N: Posterior dislocation of the

shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004;86(3):

324-332.

29. Bhler M, Gerber C: Shoulder instability

related to epileptic seizures. J Shoulder

Elbow Surg 2002;11(4):339-344.

30. Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM,

Tornetta P III: Shoulder girdle, in

Tornetta P III, Einhorn TA, eds:

Orthopaedic Surgery Essentials: Trauma.

Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott, Williams

and Wilkins, 2006, pp 68-88.

31. Spencer EE Jr, Brems JJ: A simple technique

for management of locked posterior shoulder

dislocations: Report of two cases. J Shoulder

Elbow Surg 2005;14(6):650-652.

32.

Begin M, Gagey O, Soubeyrand M: Acute

bilateral posterior dislocation of the

shoulder: One-stage reconstruction of both

humeral heads with cancellous autograft

and cartilage preservation. Chir Main

2012;31(1):34-37.

33. Matsen FA III, Titelman RM, Lippitt SB,

Rockwood CA Jr, Wirth MA:

Glenohumeral instability, in

Rockwood CA Jr, Matsen FA III,

Wirth MA, Lippitt SB, eds: The Shoulder,

ed 3. Philadelphia, PA, Saunders Elsevier,

2004, vol 2, pp 655-794.

34. Bottoni CR, Franks BR, Moore JH,

DeBerardino TM, Taylor DC, Arciero RA:

Operative stabilization of posterior

shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med 2005;

33(7):996-1002.

Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Copyright the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

You might also like

- Charalambos Panayiotou Charalambous - The Shoulder Made Easy-Springer International Publishing (2019) PDFDocument558 pagesCharalambos Panayiotou Charalambous - The Shoulder Made Easy-Springer International Publishing (2019) PDFField Jd100% (1)

- The Classification of Shoulder Instability. New Light Through Old Windows!Document12 pagesThe Classification of Shoulder Instability. New Light Through Old Windows!Christian Tobar FredesNo ratings yet

- Bench - Add 50lbs in 7 WksDocument7 pagesBench - Add 50lbs in 7 WksSaltForkNo ratings yet

- Dunnaway Reviewer 1Document38 pagesDunnaway Reviewer 1march8200871% (7)

- 52 Muscle Building TipsDocument76 pages52 Muscle Building Tipsk1l2d3100% (4)

- Giles and SandersDocument27 pagesGiles and SandersDana Ysabelle IbarraNo ratings yet

- Anterior Shoulder Instability in Sport Current Management RecommendationsDocument12 pagesAnterior Shoulder Instability in Sport Current Management RecommendationsAlexie GlóriaNo ratings yet

- Posterior Shoulder Fracture-Dislocation: An Update With Treatment AlgorithmDocument10 pagesPosterior Shoulder Fracture-Dislocation: An Update With Treatment AlgorithmAghnia NafilaNo ratings yet

- Shoulder DislocationDocument44 pagesShoulder DislocationMazvita Maz MatipiraNo ratings yet

- Shoulder-Acromioclavicular Separation PDFDocument13 pagesShoulder-Acromioclavicular Separation PDFFebrian ParuraNo ratings yet

- Shoulder Dislocation in The Older Patient: Review ArticleDocument8 pagesShoulder Dislocation in The Older Patient: Review ArticleFadhli Aufar KasyfiNo ratings yet

- Shoulder Dislocation Background: Shoulder Dislocations Traumatic InjuryDocument7 pagesShoulder Dislocation Background: Shoulder Dislocations Traumatic Injuryanastasiaanggita_265No ratings yet

- Acute and Chronic Instability of The Elbow: Bernard F. Morrey, MDDocument12 pagesAcute and Chronic Instability of The Elbow: Bernard F. Morrey, MDFadhli Aufar KasyfiNo ratings yet

- Aaos 2002Document120 pagesAaos 2002Yusufa ArdyNo ratings yet

- D.M. Rouleau - Incidence of Associated Injury in Posterior Shoulder Dislocation (2012)Document6 pagesD.M. Rouleau - Incidence of Associated Injury in Posterior Shoulder Dislocation (2012)João Pedro ZenattoNo ratings yet

- Clinical Tests of The Shoulder: Accuracy and Extension Using Dynamic UltrasoundDocument9 pagesClinical Tests of The Shoulder: Accuracy and Extension Using Dynamic UltrasoundMohammad Al AbdullaNo ratings yet

- Shoulder Injures and Management 2Document94 pagesShoulder Injures and Management 2Khushboo IkramNo ratings yet

- The Terrible Triad of The ElbowDocument5 pagesThe Terrible Triad of The Elbowapi-250084607No ratings yet

- Complete - Medullacervical - Spinal - Cord - Transection - A Case ReportDocument8 pagesComplete - Medullacervical - Spinal - Cord - Transection - A Case Reportkarisman kadirNo ratings yet

- Whiplash Associated DisordersDocument12 pagesWhiplash Associated DisorderspuchioNo ratings yet

- IOM in Scoliosis TMHDocument75 pagesIOM in Scoliosis TMHtuanemgNo ratings yet

- Manejo Via Aérea Trauma CervicalDocument26 pagesManejo Via Aérea Trauma CervicalOdlanier Erwin Castro OlivaresNo ratings yet

- Posterior Shoulder Fracture-Dislocation A SystematDocument7 pagesPosterior Shoulder Fracture-Dislocation A SystematMarcos Burón100% (1)

- William C. Cottrell, MD AbstractDocument4 pagesWilliam C. Cottrell, MD AbstractmalaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Spine Trauma and Spinal Deformities PDFDocument34 pagesPrinciples of Spine Trauma and Spinal Deformities PDFVirlan Vasile CatalinNo ratings yet

- Pelvic Injury (Autosaved)Document44 pagesPelvic Injury (Autosaved)abhishek chaudharyNo ratings yet

- Scapular Fracture in A Professional Boxer: Nashville, TennDocument4 pagesScapular Fracture in A Professional Boxer: Nashville, TennLuis Guillermo Buitrago BuitragoNo ratings yet

- Reversetotalshoulder Arthroplasty: Early Results of Forty-One Cases and A Review of The LiteratureDocument11 pagesReversetotalshoulder Arthroplasty: Early Results of Forty-One Cases and A Review of The LiteratureBruno FellipeNo ratings yet

- Return To Play Following Anterior Shoulder Dislocation and Stabilization SurgeryDocument17 pagesReturn To Play Following Anterior Shoulder Dislocation and Stabilization SurgerydrjorgewtorresNo ratings yet

- Rotator CuffDocument46 pagesRotator CuffLiza Perez- Pagatpatan100% (2)

- Dislocation Shoulder GoodDocument7 pagesDislocation Shoulder GoodZahiera NajibNo ratings yet

- Anterior Shoulder Instability A Review of PathoanatomyDocument8 pagesAnterior Shoulder Instability A Review of PathoanatomyNikita TripthiNo ratings yet

- Các Trường Hợp Lóc Da CLB Y KHOA TRẺ Y KHOA VINHDocument84 pagesCác Trường Hợp Lóc Da CLB Y KHOA TRẺ Y KHOA VINHVmu ShareNo ratings yet

- Background: FrequencyDocument15 pagesBackground: FrequencyRandi SukmanaNo ratings yet

- Manejo Inicial Trauma EspinalDocument7 pagesManejo Inicial Trauma EspinalJuan MVNo ratings yet

- Brachial Plexus NeuropathyDocument4 pagesBrachial Plexus NeuropathyKim Torreliza EjeNo ratings yet

- The Painful Shoulder: Part I. Clinical Evaluation - AAFPDocument18 pagesThe Painful Shoulder: Part I. Clinical Evaluation - AAFPMelvin Florens Tania GongaNo ratings yet

- Oite 2006Document823 pagesOite 2006dastroh100% (1)

- Intrathoracic Fracture-Dislocation of The Humeral Head: A Case ReportDocument4 pagesIntrathoracic Fracture-Dislocation of The Humeral Head: A Case ReportRachmawan WijayaNo ratings yet

- Upper Extremity Weightlifting Injuries: Diagnosis and ManagementDocument6 pagesUpper Extremity Weightlifting Injuries: Diagnosis and ManagementsinduNo ratings yet

- Shoulder Bankart Lesion With Posterior Instability A Case Report of Ultrasound DetectionDocument5 pagesShoulder Bankart Lesion With Posterior Instability A Case Report of Ultrasound DetectionSheila Setiawati TanzilNo ratings yet

- Posterior Dislocation of The Hip JointDocument25 pagesPosterior Dislocation of The Hip JointadibahNo ratings yet

- Bilateral Inter-Faceted Dislocation of Cervical Spine: Closed Reduction With Traction Weights - Small and Slow or Lose It All (Neurology)Document10 pagesBilateral Inter-Faceted Dislocation of Cervical Spine: Closed Reduction With Traction Weights - Small and Slow or Lose It All (Neurology)ICNo ratings yet

- Broken Neck (Hangman's Fracture) : DescriptionDocument5 pagesBroken Neck (Hangman's Fracture) : DescriptionFatima RizwanNo ratings yet

- SLAP Lesions of The ShoulderDocument6 pagesSLAP Lesions of The ShoulderPaula Valeria González MarchantNo ratings yet

- Sever Inferior Humeral Head Subluxation For 3 Months in Proximal Humerus Fracture DislocationDocument4 pagesSever Inferior Humeral Head Subluxation For 3 Months in Proximal Humerus Fracture DislocationIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Dislocations: Diagnosis, Management, and Complications: Marvin H. Meyers, M.D.Document12 pagesDislocations: Diagnosis, Management, and Complications: Marvin H. Meyers, M.D.Unoscientris StupaNo ratings yet

- The Painful Shoulder - Part I. Clinical Evaluation PDFDocument17 pagesThe Painful Shoulder - Part I. Clinical Evaluation PDFOscar FrizziNo ratings yet

- June1997 CC WilkDocument10 pagesJune1997 CC WilkwesleythompsonNo ratings yet

- JAAOS-Management of Hemorrhage in Life-Threatening Pelvic Fracture 162Document11 pagesJAAOS-Management of Hemorrhage in Life-Threatening Pelvic Fracture 162Enny Yunita HariantiNo ratings yet

- CR - RamirezDocument4 pagesCR - RamirezTommysNo ratings yet

- Spinal Cord InjuryDocument9 pagesSpinal Cord Injuryta CNo ratings yet

- Adhesive CapsulitisDocument20 pagesAdhesive Capsulitisvenkata ramakrishnaiahNo ratings yet

- SHOULDER INSTABILITY ManagDocument18 pagesSHOULDER INSTABILITY ManagFarhan JustisiaNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitation of Shoulder Impingement Syndrome and Rotator Cuff Injuries: An Evidence-Based ReviewDocument10 pagesRehabilitation of Shoulder Impingement Syndrome and Rotator Cuff Injuries: An Evidence-Based ReviewEduardo Santana SuárezNo ratings yet

- Aaos 2019Document283 pagesAaos 2019alealer2708No ratings yet

- Shoulder Pain EvaluationDocument8 pagesShoulder Pain EvaluationAnonymous 9lmlWQoDm8No ratings yet

- Lower Extremity TraumaDocument72 pagesLower Extremity TraumaMariamNo ratings yet

- AAOS2014 Shoulder and ElbowDocument83 pagesAAOS2014 Shoulder and ElbowAmmar HilliNo ratings yet

- Scapulothoracic Dissociation 2165 7548.1000142Document2 pagesScapulothoracic Dissociation 2165 7548.1000142Fadlu ManafNo ratings yet

- Brachial Plexus InjuryDocument20 pagesBrachial Plexus InjurySuci PramadianiNo ratings yet

- Clinical Manifestation of Acute Spinal Cord Injury, Chapter-4Document6 pagesClinical Manifestation of Acute Spinal Cord Injury, Chapter-4cpradheepNo ratings yet

- Facet DislocationDocument33 pagesFacet Dislocationgumi9No ratings yet

- Update On Traumatic Acute Spinal Cord Injury.: DOI: 10.1016/j.medine.2016.11.007Document38 pagesUpdate On Traumatic Acute Spinal Cord Injury.: DOI: 10.1016/j.medine.2016.11.007witwiiwNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Open Tracheostomy A PreliminaryDocument6 pagesPerioperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Open Tracheostomy A PreliminaryMuhammad Pringgo ArifiantoNo ratings yet

- Case Report Foreign Body (Coin) in EshopagusDocument7 pagesCase Report Foreign Body (Coin) in EshopagusMuhammad Pringgo ArifiantoNo ratings yet

- Symptom Conductive Hearing Loss.3Document3 pagesSymptom Conductive Hearing Loss.3Muhammad Pringgo ArifiantoNo ratings yet

- Management of Esophageal Foreign Bodies - A Report On 26 Patients and Literature Review (#72399) - 62028Document5 pagesManagement of Esophageal Foreign Bodies - A Report On 26 Patients and Literature Review (#72399) - 62028Muhammad Pringgo ArifiantoNo ratings yet

- Algorithm Acute Otitis MediaDocument1 pageAlgorithm Acute Otitis MediaMuhammad Pringgo ArifiantoNo ratings yet

- Algorithm Acute Otitis MediaDocument1 pageAlgorithm Acute Otitis MediaMuhammad Pringgo ArifiantoNo ratings yet

- Thyroid NoduleDocument7 pagesThyroid NodulePradhana FwNo ratings yet

- Algorithm Acute Otitis MediaDocument1 pageAlgorithm Acute Otitis MediaMuhammad Pringgo ArifiantoNo ratings yet

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in The Skeletally Immature (Pringgo)Document12 pagesAnterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in The Skeletally Immature (Pringgo)Muhammad Pringgo ArifiantoNo ratings yet

- System Policy Manual: Facility NameDocument14 pagesSystem Policy Manual: Facility NameMuhammad Pringgo ArifiantoNo ratings yet

- Ogexamination 110401040414 Phpapp02 PDFDocument26 pagesOgexamination 110401040414 Phpapp02 PDFDika RizkiardiNo ratings yet

- Fetal MonitoringDocument22 pagesFetal MonitoringMuhammad Pringgo ArifiantoNo ratings yet

- Problem Hypotesis Mechanism More Info Learning Issue Problem SolvingDocument2 pagesProblem Hypotesis Mechanism More Info Learning Issue Problem SolvingMuhammad Pringgo ArifiantoNo ratings yet

- JURNALDocument12 pagesJURNALAsMiraaaaNo ratings yet

- Fetal MonitoringDocument22 pagesFetal MonitoringMuhammad Pringgo ArifiantoNo ratings yet

- Examining Joints: How To Succeed in Clinical ExaminationsDocument12 pagesExamining Joints: How To Succeed in Clinical ExaminationsimperiallightNo ratings yet

- Adhesive Capsulitis (Frozen Shoulder)Document5 pagesAdhesive Capsulitis (Frozen Shoulder)erikaNo ratings yet

- FULL Download Ebook PDF Key Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery 2nd Edition PDF EbookDocument41 pagesFULL Download Ebook PDF Key Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery 2nd Edition PDF Ebookmary.grooms166100% (31)

- Shoulder Joint AssessmentDocument92 pagesShoulder Joint Assessmentsonali tushamerNo ratings yet

- Aksha Poster AbstractDocument14 pagesAksha Poster Abstractडॉ यश तलेराNo ratings yet

- تجميع المذكرات الاورثوDocument59 pagesتجميع المذكرات الاورثوMarah AbdulrahimNo ratings yet

- Imaging Anatomy Musculoskeletal (B. J. Manaster, Julia Crim) (Z-Lib - Org) Split-Merge - extractPDFpagesDocument12 pagesImaging Anatomy Musculoskeletal (B. J. Manaster, Julia Crim) (Z-Lib - Org) Split-Merge - extractPDFpagesChristian ToalongoNo ratings yet

- Magnus 2013Document8 pagesMagnus 2013lauracNo ratings yet

- Sports Injuries and AcupunctureDocument19 pagesSports Injuries and AcupunctureLiliana Ponte100% (1)

- Dirkwinkel Johanna Sophie Mefst 2017 Diplo SveucDocument59 pagesDirkwinkel Johanna Sophie Mefst 2017 Diplo SveucJulenda CintarinovaNo ratings yet

- Brody2012 PDFDocument13 pagesBrody2012 PDFfrancisca caceresNo ratings yet

- GIRDDocument10 pagesGIRDSérgio Xavier SilvaNo ratings yet

- Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair Protocol:: Peter J. Millett, MD, MSCDocument4 pagesArthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair Protocol:: Peter J. Millett, MD, MSCPhooi Yee LauNo ratings yet

- Catatan Orthopedi AriefDocument8 pagesCatatan Orthopedi Ariefmiwer 765No ratings yet

- Rotator Cuff DiseaseDocument53 pagesRotator Cuff Diseasematteo7099No ratings yet

- Tip - Make The Face Pull A Staple Exercise - T Nation PDFDocument2 pagesTip - Make The Face Pull A Staple Exercise - T Nation PDFsalva1310No ratings yet

- TOSSM-APKASS 2020 - Conference ProgramDocument3 pagesTOSSM-APKASS 2020 - Conference Programfajar alatasNo ratings yet

- Assignment Shoulder JointDocument7 pagesAssignment Shoulder JointMary Grace OrozcoNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of High-Intensity Laser Therapy in The TreatmentDocument9 pagesThe Effectiveness of High-Intensity Laser Therapy in The TreatmentDiego Pinto PatroniNo ratings yet

- Operative Techniques Orthopaedic Trauma Surgery 2Nd Edition Emil H Schemitsch Download PDF ChapterDocument51 pagesOperative Techniques Orthopaedic Trauma Surgery 2Nd Edition Emil H Schemitsch Download PDF Chaptermary.hanna173100% (5)

- Current Views of Scapular Dyskinesis and Its Possible Clinical RelevanceDocument14 pagesCurrent Views of Scapular Dyskinesis and Its Possible Clinical RelevanceRoshani PNo ratings yet

- SaudiJHealthSci4142-1740933 045009Document9 pagesSaudiJHealthSci4142-1740933 045009Ramona BordeaNo ratings yet

- Effective Functional Progression of Sports RehabDocument251 pagesEffective Functional Progression of Sports RehabAnonymous IbLWfV4Nt89% (9)

- Rotator Cuff Impingement TestsDocument29 pagesRotator Cuff Impingement TestsFarwaNo ratings yet

- The Rotator Cuff (Myofascial Techniques)Document4 pagesThe Rotator Cuff (Myofascial Techniques)Advanced-Trainings.com100% (3)