Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Criminology Essay 2

Uploaded by

api-325126195Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Criminology Essay 2

Uploaded by

api-325126195Copyright:

Available Formats

LAW 638

124342

Human rights and the law of sex offences Drawing

lines in shifting sands

On its face, there is clearly some tension here between the declaration of

fundamental rights and the declaration of victims rights. This is

symptomatic of a more widespread tension between the universality of

human rights and concreteness of the legal practises in which it emerges,

as well as the embedded quality of the social practises it wants to

manage.1

1 Peter D. Rush in Clare McGlynn and Vanessa E. Munros (eds) Rethinking Rape

Law (2010) 240.

1

LAW 638

124342

This essay will discuss the human rights implications of sexual offences in

the Tasmanian judicial context. It draws upon a number of international

covenants and treaties to illustrate a standard that can be applied to the

Tasmanian law in order to better articulate the interests of those involved

in a sexual offence matter. This essay contemplates these rights in

relation to the statutory definitions of both rape2 and consent3 under the

Tasmanian Criminal Code. It also considers the implementation of this

legislation, as well as the application of the laws of evidence 4, in light of

current procedural practise. In conclusion this essay establishes that it is

inevitable that some rights will be compromised in judicial proceedings

pertaining to the prosecution of sexual offences. It is therefore of pivotal

importance that all parties are equally equipped and represented by the

law throughout this process,5 and that public discourse continues in

relation to the shifting boundaries of lawful and unlawful sex.

In the context of sexual offences, this essay identifies a number of key

provisions which may inform6 the creation and implementation of

2 Criminal Code 1924 (Tas) s 185.

3 Criminal Code 1924 (Tas) s 2A.

4 Evidence Act 2001 (Tas).

5 See Fiona E. Raitt in Clare McGlynn and Vanessa E. Munros (eds) Rethinking

Rape Law (2010) 268.

6 In the absence of an Australian charter or bill of rights, human rights law in

Australia stems from specific domestic legislation, such as the Racial

Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth), several select common law rights and through the

recognition of International agreements and treaties. It is therefore difficult to

2

LAW 638

124342

legislation governing sexual offences in Tasmania. These provisions

demonstrate standards that have been established in other jurisdictions

regarding the rights that ought to be enjoyed by both defendants and

complainants in criminal proceedings.7 The legislation this essay will draw

upon includes international agreements such as the Universal Declaration

of Human Rights (UDHR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights (ICCPR) and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

The recent developments regarding the Victorian Charter of Human Rights

and Responsibilities and the High Court decision in Momcilovic8 are also

an interesting case study within the domestic law context 9. These

declarations can be juxtaposed with the Criminal Code Act 1924 (Tas) (the

Code) and the Evidence Act 2001 (Tas) in order to illustrate the human

rights implications of sexual offences in the Tasmanian jurisdiction.

THE STATUTORY DEFINITIONS OF RAPE AND CONSENT

discern whether such principles are binding on Australian courts, or where the

judiciary will choose to recognise them. However, for the purpose of this essay,

these provisions provide a general standard that can be applied in order to better

understand the complex rights of all respective players involved in sexual

offence matters.

7 The rights this essay implicates are also critical for the law itself, and for the

institution of the judiciary, as will be further discussed.

8 Momcilovic v The Queen & Ors [2011] HCA 34.

9 See also the Australian Constitution s 80.

3

LAW 638

124342

The codification of the crime of rape has been subject to ongoing reform. 10

This is in part due to the attempts of the legislature to better delineate the

context in which the generally accepted behaviour of sexual intercourse

ought to constitute a criminal offence.11 Legislators are in effect searching

for a grand theory, founded in moral certainty, which will identify the

particular scenarios in which an offender is deserving of conviction. 12

However, the equation of law with Platonic ideals of morality 13 is a

dangerous assumption as it presupposes the existence of commonly held,

moral objectives. This is not consistent with the views of contemporary

commentators, such as Ngaire Naffine, who recognises that morality is a

relative concept.14 The law therefore ought to reflect the complex society

in which it is to operate and the interests of the real people and real

institutions15 that Naffine articulates. This requires a careful balancing of

the values of current society, with notions of what is just and equitable.16

10 Criminal Code Amendment (Sexual Offences) Act 1987 (Tas) and Criminal

Code Amendment (Consent) Act 2004 (Tas).

11 Kate Warner Sexual Offending: Victim, Gender and Sentencing Dilemmas in

Duncan Chappell and Paul Wilson (eds) Issues in Australian Crime and Criminal

Justice (2005) 236-7.

12 Note Ngaire Naffines notions of mala in se and mala prohibita in Ngaire

Naffine Moral Uncertainties of Rape and Murder: Problems at the Core of

Criminal Law Theory in McSherry B, Norrie A and Bronitt S (eds) Regulating

Deviance (Hart Publishing, 2009).

13 For an example, see Platos allegory of The Cave.

14 Ngaire Naffine Moral Uncertainties of Rape and Murder: Problems at the Core

of Criminal Law Theory in McSherry B, Norrie A and Bronitt S (eds) Regulating

Deviance (Hart Publishing, 2009).

15 ibid.

16 Clearly, this is a difficult task as notions of what is just and equitable naturally

extend from the values society holds. See Cockburn H, The Impact of Introducing

an Affirmative Model of Consent and Changes to the Defence of Mistake in

4

LAW 638

124342

The task of the legislator is thus inherently difficult as the codification of a

crime must be applicable to a variety of differing scenarios. Further, it

should recognise the parties affected by the act of committing and

convicting an offence, including the rights and interests of the accused,

the complainant, the public and the construct of the law itself. If the crime

of rape is defined too broadly, the right of a defendant to be innocent until

proven guilty17 and the right to a fair trial18 may be unduly compromised if

conviction occurs without due investigation into the complainants claims.

Conversely, if the provision is too specific and convictions do not

correspond with the harm inflicted, this may cause further harm to the

complainant and arguably is not in the interests of the public. 19

Furthermore, it is in the interests of the law and legal institutions that the

law is consistent with societal values and that it is applied fairly. The

conflicts between these amalgams of interests and rights are evident

upon closer analysis of the Tasmanian situation.

The crime of rape under the Code establishes that where sexual

intercourse20 occurs in the absence of valid consent the perpetrating party

Tasmanian Rape Trials (University of Tasmania, 2012) 190.

17 See, for example, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, s

14(2) and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 11(1).

18 See, for example, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, s

14(1), Charter for Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) s 24 and the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 10.

19 For a discussion on the contraction and expansion of the scope of the

definition of rape see Peter D. Rush in Clare McGlynn and Vanessa E. Munros

(eds) Rethinking Rape Law (2010) 244.

20 Sexual intercourse is defined under the Criminal Code Act 1924 (Tas) s 1 as

penetration to the least degree of the vagina, genitalia, anus, or mouth by the

penis and includes the continuation of sexual intercourse after such penetration.

5

LAW 638

124342

is guilty of an offence.21 The key element to be established and negated

by the court is whether or not the required consent exists on the facts.

The definition of consent and its interpretation by the court is therefore an

influential factor in establishing the criminal liability of the accused. In the

Tasmanian jurisdiction recent reforms22 have implemented an affirmative

model of consent, which places a greater onus on the accused and goes

some way in addressing the traditionally held sexist stigmas surrounding

complainants in rape cases.23

This model has received mixed reviews. Dan Subotnik argues that it is

neither practical nor appropriate to apply an affirmative model of consent

to the fundamentally animalistic behaviour of sexual intercourse, 24 and

that the model unfairly prejudices the accuseds right to be deemed

innocent until proven guilty. Alternatively, Helen Cockburn contends that

the reforms may be largely symbolic, and that without broad attitudinal

change at the societal level, the state of the law remains at odds with the

rights and interests of complainants.25 This is particularly resonant in

21 Tasmanian Criminal Code, s 185.

22 Criminal Code Amendment (Sexual Offences) Act 1987 (Tas) and Criminal

Code Amendment (Consent) Act 2004 (Tas).

23 Kate Warner highlights the focus of the reforms in defining consent in positive

terms as to more properly reflect the two objectives of sexual offences: the

protection of sexual autonomy and freedom of choice for adults, see Kate

Warner Sexual Offending: Victim, Gender and Sentencing Dilemmas in Duncan

Chappell and Paul Wilson (eds) Issues in Australian Crime and Criminal Justice

(2005) 240.

24 Royal College of Art London, Rape and the Law: He Said, She Said (2010)

YouTube <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vmM5X-NSUhc> at 24 May 2013.

25 Cockburn H, The Impact of Introducing an Affirmative Model of Consent and

Changes to the Defence of Mistake in Tasmanian Rape Trials (University of

Tasmania, 2012) 188.

6

LAW 638

124342

relation to female complainants, and it has been suggested that the state

plays some role in indirectly fostering the subordination of women in

society.26 This is evinced further below.

PROCEDURE AT TRIAL IN RAPE CASES

In the context of human rights, procedural rules and the laws of evidence

provide the greatest challenge to party interests in sexual offence

matters. This is the result of the influence of the judiciary and its capacity

to interpret legislation in light of societal standards and their personal

beliefs and values, as well as the powers exercised by public juries. Rape

shield legislation has been enacted in Tasmania by virtue of s 194M of the

Evidence Act 2001 (Tas) to protect complainants against the armoury of

intimidating tactics employed by the defence 27, and to prevent juries from

making prejudicial assumptions about the complainants sexual integrity.

However, the legislation has not operated as it should, as in most cases

evidence relating to the complainants sexual experience is deemed

admissible under the exceptions to s 194M in s 194M(2)-(3) 28. This has led

critics to argue that the capacity for rape shield legislation to produce

26 Alice Edwards in Clare McGlynn and Vanessa E. Munros (eds) Rethinking

Rape Law (2010) 96.

27 Fiona E. Raitt in Clare McGlynn and Vanessa E. Munros (eds) Rethinking Rape

Law (2010) 274.

28 The Evidence Act 2001 (Tas) s 194M(2) states A magistrate or judge must not

grant leave unless satisfied that (a) the evidence sought to be adduced or

elicited has direct and substantial relevance to a fact or matter in issue; and (b)

the probative value of the evidence outweighs any distress, humiliation or

embarrassment which the person against whom the crime or offence is alleged

to have been committed might suffer as a result of the admission of evidence.

7

LAW 638

124342

instrumental change is limited,29 until the rights of victims in the trial

context are given greater recognition by the legal profession.

Therefore, the human rights debate regarding rape trial process is

perceived as a direct conflict between the interests of the defendant and

the interests of the complainant. On the one hand, defendants possess a

firmly entrenched right to a fair trial, in which they are deemed innocent

until proven guilty. This right is recognised under s 14(2) 30 of the ICCPR

and per Article 11(1)31 of the UDHR, and was positively reaffirmed by the

Australian High Court in the cases of R v Oakes32 and Momcilovic33. Such

rights are justified by the rule of law, and are at the heart of adversarial

system.34

Comparatively, victim lobbies are critical of the defendant-protective

philosophical base from which judicial process operates. 35 Although the

afore noted instruments of human rights law do not expressly articulate

rights of the complainant, it is contended by some scholars such as Fiona

E. Raitt that it is possible to interpret several articles of the ECHR as

recognising the interests of victims in rape trial scenarios. 36 Such

29 Fiona E. Raitt in Clare McGlynn and Vanessa E. Munros (eds) Rethinking Rape

Law (2010) 273.

30 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, s 14(2).

31 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 11(1).

32 R v Oakes [1986] 1 SCR 103.

33 Momcilovic v The Queen & Ors [2011] HCA 34.

34 Jeremy Gans et al, Criminal process and Human Rights (2011) 498.

35 ibid 512-513.

8

LAW 638

124342

interpretation is evinced in the Canadian jurisdiction by LHeureux Dub J,

who argues passionately that a

fair legal system requires respect at all times for the complainant's

personal dignity, and in particular his or her right to privacy,

equality and security of the person.37

Further, LHeureux Dub J implores that such rights should be placed on

equal footing with those of accused persons. 38 Thus it remains to be

adduced how the judicial system is to consolidate the rights of defendants

with the interests of complainants. It has been suggested in public

discourse that due to the extent of previous legislative reform, the

impediment for greater justice in the rape cases lies with society and their

belief in so-called rape myths.39

SEXISM AND SEXUAL OFFENCES

Kate Warner has stated that while it may be relatively simple to change

the meaning of rape in the statute books, changing its meaning in

36 Fiona E. Raitt in Clare McGlynn and Vanessa E. Munros (eds) Rethinking Rape

Law (2010) 276, specifically, ss 3, 18, 13 of the European Convention on Human

Rights.

37 LHeureux Dub J in R v OConnor [1995] 4 SCR 411 at 154. For recognition of

privacy rights in the Australian context see Toonen v Australia, Communication

No. 488/1992.

38 ibid.

39 Royal College of Art London, Rape and the Law: He Said, She Said (2010)

YouTube <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vmM5X-NSUhc> at 24 May 2013.

9

LAW 638

124342

practise is another matter.40 Here Warner is referring to social perceptions

of what rape is and is not, and the influence these perceptions have on

the indictment of sex offenders. Arguably, previous reform has failed to

acknowledge rape as a gendered crime 41 and that attitudes towards rape

come from the same place as societys attitude towards women

generally.42 This process is cyclical as the law also impacts significantly

upon societal values, and thus both need to be considered in conjunction

with the other. As noted earlier in this paper, the rationalisation of social

understandings with the prescriptions of the legislature is an inherently

difficult task. However as Warner articulates, the struggle to address the

underlying masculinist assumptions that structure the law ought to

continue, so that legal understandings of the harms related to rape reflect

the experiences of victims.43

REFORM OBJECTIVES FOR THE FUTURE

40 Kate Warner Sexual Offending: Victim, Gender and Sentencing Dilemmas in

Duncan Chappell and Paul Wilson (eds) Issues in Australian Crime and Criminal

Justice (2005) 247.

41 Peter D. Rush in Clare McGlynn and Vanessa E. Munros (eds) Rethinking Rape

Law (2010) 238.

42 Marguerite Russell in Royal College of Art London, Rape and the Law: He Said,

She Said (2010) YouTube <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vmM5X-NSUhc> at

24 May 2013.

43 Kate Warner Sexual Offending: Victim, Gender and Sentencing Dilemmas in

Duncan Chappell and Paul Wilson (eds) Issues in Australian Crime and Criminal

Justice (2005) 249.

10

LAW 638

124342

It is difficult to say definitively why past reforms to the law of sexual

offences in Tasmania have had only limited success. One possibility that is

suggested is that the reforms meet continuing resistance from the public,

and therefore reconstructing the legal definition of rape alone may not be

sufficient to effect real reform. 44 This has led commentators to propose a

number of new and creative reforms, which range from the sublime to the

ridiculous.45 One proposition as advocated by Raitt is the introduction of

independent legal representation (ILR) for complainants in rape trials. 46

Undoubtedly, the implication of such a scheme would go some way in

ensuring that the trial process is not excessively isolating and intimidating

for victims, and that complainants are able to participate effectively. 47

Warner has also suggested that guidelines for judges, specifying the

requirements of their directions to juries and their use of s 194M(2), would

also be appropriate.48 Finally however, a warning should be sounded

regarding reform objectives which are too far removed from the consensus

of beliefs held by general society. In a similar vein, Helen Reece supposes

that perhaps the views of society are justified, and that it would be

44 Peter D. Rush in Clare McGlynn and Vanessa E. Munros (eds) Rethinking

Rape Law (2010) 238.

45 Royal College of Art London, Rape and the Law: He Said, She Said (2010)

YouTube <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vmM5X-NSUhc> at 24 May 2013

46 Fiona E. Raitt in Clare McGlynn and Vanessa E. Munros (eds) Rethinking Rape

Law (2010) 268.

47 ibid.

48 Kate Warner Sexual Offending: Victim, Gender and Sentencing Dilemmas in

Duncan Chappell and Paul Wilson (eds) Issues in Australian Crime and Criminal

Justice (2005) 248.

11

LAW 638

124342

inappropriate to hold out the views of a minority of reformers as the right

perspective to be taken.

49

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

This essay has demonstrated the difficulties involved in establishing just

and equitable laws governing sexual offences in Tasmania. The application

of human rights principles to the definition of rape under the Code and the

laws of evidence applicable at trial demonstrates the multiplicity of

interests that the law has a moral and legal duty to uphold. Further, as the

title of this paper suggests, the implication of principles of human rights is

problematic given the sovereignty of national law and the day to day

social behaviours it tries to rationalise. Nevertheless, this essay concludes

that continuing discourse on this topic is inexhaustibly beneficial to the

creation and implementation of the best possible legislative and

procedural law regarding sexual offences. As Warner recognises, this

requires a collective approach to reform which provokes lawyers, judges,

juries and the public to reflect critically about what constitutes rape and

the shifting boundaries between rape and lawful sex. Clearly, as Warner

implores, we cannot leave sexual assault to the criminal law alone.50

49 Helen Reece in Royal College of Art London, Rape and the Law: He Said, She

Said (2010) YouTube <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vmM5X-NSUhc> at 24

May 2013.

50 Kate Warner Sexual Offending: Victim, Gender and Sentencing Dilemmas in

Duncan Chappell and Paul Wilson (eds) Issues in Australian Crime and Criminal

Justice (2005) 248.

12

LAW 638

124342

1,990 words.

13

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Christophe Bouton - Time and FreedomDocument294 pagesChristophe Bouton - Time and FreedomMauro Franco100% (1)

- BidDocument Phase 3 Package-9 (58) Lot-1 RebidDocument150 pagesBidDocument Phase 3 Package-9 (58) Lot-1 RebidT TiwariNo ratings yet

- Non-Violent Crisis Intervention - Suicidal ThreatsDocument9 pagesNon-Violent Crisis Intervention - Suicidal Threatspromoth007100% (2)

- Acct4131 AuditingDocument2 pagesAcct4131 AuditingWingyan ChanNo ratings yet

- Advantages of Rizal LawDocument5 pagesAdvantages of Rizal LawClark Vince Caezar Afable80% (15)

- Research Objectives, Questions HypothesisDocument42 pagesResearch Objectives, Questions HypothesisZozet Omuhiimba100% (2)

- UNFPA Career GuideDocument31 pagesUNFPA Career Guidealylanuza100% (1)

- Eapp Q2Document20 pagesEapp Q2Angeline AdezaNo ratings yet

- Character SketchDocument3 pagesCharacter Sketchsyeda banoNo ratings yet

- Democ Paper South Africa 1Document6 pagesDemoc Paper South Africa 1api-337675302No ratings yet

- Datalift Movers v. BelgraviaDocument3 pagesDatalift Movers v. BelgraviaSophiaFrancescaEspinosaNo ratings yet

- School PlanningDocument103 pagesSchool PlanningAjay LalooNo ratings yet

- Marriage Seminar Lesson1 CommunicationDocument6 pagesMarriage Seminar Lesson1 CommunicationJeroannephil PatalinghugNo ratings yet

- Operational Development PlanDocument3 pagesOperational Development PlanJob Aldin NabuabNo ratings yet

- Frederic Chopin and George Sand RomanticizedDocument11 pagesFrederic Chopin and George Sand RomanticizedAleksej ČibisovNo ratings yet

- Barangay Resolution SampleDocument2 pagesBarangay Resolution SampleReese OguisNo ratings yet

- Indemnity BondDocument2 pagesIndemnity BondMohammad ArishNo ratings yet

- Best Practices of Inclusive EducationDocument17 pagesBest Practices of Inclusive EducationNaba'a NGO67% (3)

- Prophet Muhammad (Pbuh) Ethics, Leadership and Communication 10202009Document219 pagesProphet Muhammad (Pbuh) Ethics, Leadership and Communication 10202009Ali Zohery, Ph.D.88% (8)

- First PageDocument5 pagesFirst PageRais AlamNo ratings yet

- Opaud NotesDocument13 pagesOpaud NotesGOJO MOJOJOJONo ratings yet

- Grammar Practice Worksheet 1Document5 pagesGrammar Practice Worksheet 1MB0% (2)

- TikTok Brochure 2020Document16 pagesTikTok Brochure 2020Keren CherskyNo ratings yet

- Proposal Submitted To HDFC ERGODocument7 pagesProposal Submitted To HDFC ERGOTathagat JhaNo ratings yet

- Economic and Social Environment Solved Assignment Q6Document2 pagesEconomic and Social Environment Solved Assignment Q6prakash jhaNo ratings yet

- HDR 2Document58 pagesHDR 2Maharani IndriNo ratings yet

- CPPDSM4008A Manual Part 2.v1.1Document114 pagesCPPDSM4008A Manual Part 2.v1.1grace rodriguez50% (2)

- Judgment of Chief Justice J.S. Khehar and Justices R.K. Agrawal, S. Abdul Nazeer and D.Y. ChandrachudDocument265 pagesJudgment of Chief Justice J.S. Khehar and Justices R.K. Agrawal, S. Abdul Nazeer and D.Y. ChandrachudThe WireNo ratings yet

- 4 History and Philosophy of ScienceDocument40 pages4 History and Philosophy of ScienceErben HuilarNo ratings yet

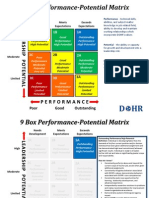

- 9 BoxDocument10 pages9 BoxclaudiuoctNo ratings yet