Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants

Uploaded by

Kath GloverCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants

Uploaded by

Kath GloverCopyright:

Available Formats

Folklore

ISSN: 0015-587X (Print) 1469-8315 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfol20

How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants?

Ronald Hutton

To cite this article: Ronald Hutton (2011) How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants?,

Folklore, 122:3, 235-249, DOI: 10.1080/0015587X.2011.608262

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0015587X.2011.608262

Published online: 03 Nov 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 3527

View related articles

Citing articles: 2 View citing articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfol20

Download by: [151.229.70.218]

Date: 28 October 2015, At: 06:27

Folklore 122 (December 2011): 235249

THE TWENTY-NINTH KATHARINE BRIGGS MEMORIAL LECTURE,

NOVEMBER 2010

How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants?

Ronald Hutton

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

Abstract

During the first two-thirds of the twentieth century, it was commonplace among

historians that the common people of medieval England had remained

substantially pagan in their religious beliefs. Christianity, according to this view,

was essentially the faith of the elite, with the populace embracing what was at best

a dual allegiance to the new and old religions. This view has now disappeared,

and the time seems right to take stock of medieval popular religion in England

with a view to solving three problems: why did the concept of a pagan medieval

populace develop, flourish for so long and then decline; what is the actual

evidence for medieval popular belief; and what new perspectives can be taken on

medieval English Christianity by employing comparisons with paganism?

Introduction

It is a great honour to be invited to give a lecture in this famous series, and I have

accordingly chosen a subject that both has some relevance to folklore studies and

features some of the most distinguished past members of The Folklore Society. The

question that I have posed concerning it needs to be understood in the crudest and

most straightforward sense: to what extent any of the common people of medieval

England self-consciously followed a surviving pagan religion. In taking this

course I must recognise at once that my chosen sense is not that usually now

adopted by scholars of the period. For example, when Ludo Milis edited a

collection entitled De heidense Middeleeuwen (1991) [The Pagan Middle Ages, 1998], it

was concerned instead with two very different phenomena: the process of

conversion from paganism to Christianity, and the manner in which pagan ideas,

images and practices survived embedded in medieval culture. The question of

pagan survivals, in that sense, was of course central to the early preoccupations

of the discipline of folklore, and it actually remains so to any consideration of

western culture. The names of the days of the week, the months of the year and the

constellations in the sky continue to be resolutely pagan, and classical pagan

motifs persisted in medieval literature and to a much lesser extent in medieval art;

in both, they were of course to experience a tremendous expansion at the end of

the Middle Ages and thereafter. In Christianity itself, many of trappings of ritual,

and the form of buildings, were taken over from the pagan ancient world. In a

more subtle fashion, pre-Christian ways of thought remained embedded in both

learned science and folk medicine, whilein a manner less often appreciatedan

active veneration of ancient deities was smuggled back into scholarly Christian

cosmology in the guise of planetary spirits (Hutton 2004). In this sense, to be partly

pagan is simply to be anybody living in the European and Mediterranean worlds

ISSN 0015-587X print; 1469-8315 online/11/030235-15; Routledge Journals; Taylor & Francis

q 2011 The Folklore Society

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0015587X.2011.608262

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

236

Ronald Hutton

at any time since the end of antiquity: which is why I am not interested in it

tonight.

What at first sight seems a much simpler and crasser interpretation of the

question can, I would argue, usefully highlight a set of other considerations that

have considerable relevance to the study of medieval culture, and perhaps even to

that of English culture in general. The first is that the question is in fact very rarely

posed directly by academics in the present day, for two reasons. One of these

consists of the compartmented nature of the research required to give it a

satisfactory answer. As posed, the question cuts through all three of the

conventional divisions of the Middle Ages, the Anglo-Saxon, high medieval and

late medieval. It requires reference to legal records, theological tracts, modern

folklore, and religious art and architecture. Finally, it demands the inter-relation of

a large amount of new material derived from scholars in a range of different

disciplines. The second reason for current neglect of my question is that the

answer to it now seems to be obvious, and firmly negative. This is because the

main structures of interpretation that had seemed to support a different answer

for most of the twentieth century have now collapsed, leaving a certain sense of

embarrassment and revulsion in their wake. This phenomenon itself says some

interesting things about changing fashions in modern intellectual tradition, and

will form the first section of my analysis.

The Altering Scholarly Consensus

In the first half of the twentieth century, there was a very strong disposition among

scholars to believe that in medieval England Christianity represented no more

than a veneer, concentrated among the elite and barely penetrating the mass of the

population, which continued to adhere, for all practical purposes, to the old

religion. It was perhaps summed up most famously by the great historian of

monasticism, Geoffrey Coulton, who claimed that in church, the women

crowded around Mary, yet they paid homage to the old deities by their nightly

fireside, or at the time-honoured sacred haunts, grove or stone or spring (Coulton

1925, 182 3). Such a view persisted into the 1970s, and was projected onto the

whole of Europe, arguably to greatest effect by Jean Delumeau, who claimed that

the true conversion of ordinary Europeans to Christianity only occurred with the

Reformation and Counter-Reformation of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries

(Delumeau 1971). I have examined the emotional roots of this construct elsewhere

(Hutton 1998, 112 31), and suggested that they lay in two different impulses. One

was the sense of alienation and fear experienced by many educated Europeans

between 1850 and 1914, on finding themselves in charge of two new and

frightening forms of mass population: the industrial and urban working classes

and the subject peoples of colonial territories. A view of civilisation as something

spread precariously over a populace who are essentially alien to it, and disaffected

from it, runs through the writings of the age. The other impulse consisted of a

growing disenchantment with conventional Christianity. At times this resulted in

a desire to dilute it, rather than abandon it, by mixing in elements from other

religions, including paganism. At others, the same disenchantment manifested as

outright hostility towards Christianity. It was clearly satisfying to those possessed

by it to see the Middle Ages, traditionally regarded as the greatest epoch of fervent

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants?

237

Christian faith, apparently to be revealed instead as a time in which most people

still revered pagan deities.

One aspect of this kind of medievalism needs to be emphasised here: that

the evidence which underpinned it was mainly derived not from a study of

medieval records themselves, but from other sources: from apparent survivals

of medieval customs, from later written evidence, and from the physical remains

of medieval buildings. Here folklorists played a crucial role, in articulating, and

providing data for, the belief that most of the customs of British country people,

especially at seasonal festivals, were remnants of pagan worship. Members of this

society also were prominent in other intellectual enterprises that powerfully

reinforced the image of the pagan Middle Ages. By far the most celebrated was

Margaret Murray, whose researches into early modern trial records seemed to

have clinched the nineteenth-century hypothesis that the individuals accused of

witchcraft in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries had been practitioners of a

surviving pagan religion. It may perhaps be necessary to emphasise once more

that this became the scholarly orthodoxy throughout the mid-twentieth century,

repeated by historians as eminent as Sir Stephen Runciman, Christopher Hill and

Sir George Clark (Clark 1945, 245 8; Runciman 1962; Hill 1967, 115 18). In itself, it

seemed to prove the existence of a robust popular paganism all through the

Middle Ages, and Margaret Murray started another hare in this direction, by

looking at the figures carved in medieval English churches. In particular, she drew

attention to the occasional representations of naked women with spread legs,

conventionally known by the Irish folk nickname of sheela-na-gigs. These she

interpreted as icons of fertility goddesses, installed in Christian buildings because

their cults remained so strong among ordinary people (Murray 1934). It was

almost certainly her example which inspired another member of this society, Lady

Raglan, to propose a similar purpose for the much more common medieval church

decorations of foliate heads. She conflated these with the vegetation-clad figure

from English May processions, the Jack in the Green, to suggest that they

represented enduring reverence for a pagan fertility god. To this entity she gave

the general term, taken from a common pub sign showing a forester, of the Green

Man (Raglan 1939). These interpretations of the two carved church figures

continued to be proposed through the centre of the century. In 1973 the pioneering

scholar of Iron Age British religion, Anne Ross, contributed an essay to Katharine

Briggss Festschrift that restated the view of the sheela-na-gig as proof of the living

cult of a pagan goddess (Ross 1973). Two years later, she and Ronald Sheridan did

not merely repeat as fact the idea that medieval grotesque art represented

enduring pagan deities but added further kinds of image to the list and accused

academic scholars of almost a conspiracy of silence in refusing to integrate this

truth into general histories of the period (Sheridan and Ross 1975). There was, of

course, no conspiracy, but an absence of any focused and sustained research. In

that absence, popular culture readily absorbed the concepts published by the writers

cited above, especially Anne Ross. The sheela-na-gig became a potent symbol for

feminist artists in the 1980s, and the Green Man an icon of the environmental

movement. As such, both are now important and dynamic modern images.

It was only in the 1970s that sustained scholarly investigation began of both the

Murray thesis and the pagan interpretation of medieval church images, and they

rapidly collapsed under the impact. Margaret Murrays reading of the witch trials

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

238

Ronald Hutton

was abandoned by all specialists in the subject by the end of the decade (Hutton

1998, 362 and 378 9). Lady Raglans composite figure of the Green Man was

dismantled component by component. In 1979 our own Roy Judge proved that the

Jack-in-the-Green had no connection with the church decorations but had evolved

out of a London chimney sweeps dance in the late eighteenth century (Judge

1979). From 1978 onward, Kathleen Basford, Rita Wood, Mercia MacDermott and

Richard Hayman have shown between them that nobody associated the foliate

heads in medieval churches with paganism before the twentieth century. They

appeared mainly in buildings commissioned by members of the elite, rather than

those in which common people had influence, and were especially popular in the

later rather than the earlier Middle Ages. The ancient precedents for them are few

and do not provide exact parallels, and the first appearance of what became the

standard form of them was in manuscripts produced in tenth-century

monasteries. It got into churches only in the twelfth century, and it is possible

that its ultimate point of origin is in India, from which it was transmitted to

European culture through the Arab world (Basford 1978; Wood 2000; MacDermott

2003; Hayman 2008; 2010). Between 1977 and 1986, Jorgen Andersen, Anthony

Weir and James Jerman similarly re-evaluated the sheela-na-gig, revealing that

this image appeared in eleventh-century France, as part of a new repertoire of

decoration associated with the evolving style of Romanesque. From there it spread

quite rapidly to Spain and England, where its popularity peaked in the twelfth

and thirteenth centuries: it did not enjoy the continued and increasing interest that

the foliate heads provoked in the later medieval period. Its purpose, taken in

context with the other forms in the repertoire, was to warn against the horrors and

temptations of carnal lust (Andersen 1977; Weir and Jerman 1986). The most

famous sheela-na-gig in England is now probably that in Kilpeck church,

Herefordshire, which also contains an early example of a foliate head. It was

indeed the type specimen used by Margaret Murray to underpin her original

theory. The church is now known to have been built by the Norman lord of the

village, a courtier and royal official called Hugh, who imported masons working

in the new Romanesque style as part of a deliberate imposition of Continental

culture on that part of England (Thurlby 1999).

It is worth pointing out that there are some rather large loose ends lying

around in this new set of interpretations. Brandon Centerwall has drawn attention

to the existence of figures actually called Green Men who appeared in Tudor

and Stuart English pageants and entertainments, as leaf-covered men carrying

clubs. They also feature on sixteenth-century wooden fittings in a church and a

cathedral. Their association seems to be with drunkenness, mirroring the

traditional use of foliage as a sign for the sale of alcohol, but how they relate to the

foliate heads, if at all, we do not yet know (Centerwall 1997). Moreover, we still do

not really know what the foliate heads themselves signified. The best hope for

discovering the answer must surely lie in a systematic examination of late

medieval English sermons and devotional works, with a concentrated purpose of

uncovering apparent references to the motif; but nobody has as yet undertaken

this.

As for the sheelas, it has always been recognised that they spread to Ireland as

well as to England (although not to Scotland), and became especially popular

there. The Irish examples, however, were increasingly placed in positions where

How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants?

239

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

the human eye could not reach, and on secular buildings such as castles in

addition to churches. They may be linked in such contexts to a tradition recorded

in much later Irish folklore, by a German traveller in the 1840s, that misfortune (in

general) could be averted by the display of a womans genitals (cited in Andersen

1977, 23). Here there might be a direct relevance to surviving ideas from ancient

paganism, which could be associated with goddesses, as some scholars have

indeed suggested in recent years (Kelly 1992; 2006; Karkov 2001). In other words,

in this specific and limited case, Margaret Murray and Anne Ross could possibly

have been correct, and especially the latter, who drew most of her material from

Ireland. None of this, however, does anything to rescue the twentieth-century use

of church carvings as evidence for a continuing and active paganism in England.

Direct and Contemporary Evidence

Now that all these red herrings have been removed from the subject, it is worth

asking what direct evidence can be produced for the presence or disappearance of

active paganism in the English Middle Ages. It may be suggested that there are

two principal bodies of it, which derive from opposite ends of the period. The first

consists of the law codes issued by Anglo-Saxon kings and the edicts of early

English church councils. Those from the late seventh century, just after the formal

conversion to Christianity, certainly forbid the continued worship of the old

deities. However, none of the texts from the eighth century do so, and indeed the

only pair that forbid non-Christian practicesthe Canons of Egbert, Archbishop of

York, from around 740, and the rulings of the Church Synod of 786 7are

concerned with what would now be called superstitions or operative magic rather

than an active continuation of the former religion (Commissioners of Public Works

1840, passim; Johnson 1850, vol. 1, 219; Haddan and Stubbs 1871, vol. 3, 189; Gee

and Hardy 1896, 41 2). This would seem to harmonise with the impression given

by Bedes famous History, completed around 740: that paganism itself was defunct

by that time. There was a further flurry of prohibitions of pagan practices in

northern England in 1000 2, issued by Wulfstan, Archbishop of York, but these

may be explained by a new influx of pagan settlers represented by the Viking

conquests in the region. In the early 1020s King Canute incorporated Wulfstans

directives into a law code for his whole realm, but after this nothing more is heard

of the problem (Commissioners of Public Works 1840, passim; Whitelock, Brett and

Brooke 1981, vol. 1, 304 5, 309, 319, 409, 461 3 and 489). This would accord with

the impression given by all other sources, of a relatively swift and easy absorption

of the Danish and Norwegian newcomers in Anglo-Saxon Christendom.

The body of evidence from the other end of the period consists of the records of

church courts, which are relatively plentiful for the fifteenth and sixteenth

centuries and dealt routinely with cases of religious heterodoxy as well as with

probate of wills and all kinds of moral offences. They certainly reveal an enduring

condemnation of the established Church, covering most of its core doctrines and

institutions. Although this was expressed by a small minority of the population,

concentrated in certain districts of southern and central England, it was

determined and persistent. Historians have adopted for those who articulated it

the contemporary abusive term of Lollards. They were, however, not pagans but

the direct opposite: very devout Christians who happened to disagree profoundly

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

240

Ronald Hutton

with the interpretation of Christianity made by medieval Catholicism. In addition,

the same records contain an equally persistent number of cases of individuals who

mocked aspects of Christian piety. They were even fewer than the Lollards,

belonged to no continuous and articulated rival tradition, and did not argue for

any alternative system of religion: they were either exercising their wit at the

expense of the pious or else expressing a scepticism concerning the value of any

religious faith. What the court archives of the period embody very strongly is a

sense that unorthodox religious or moral beliefs by individuals threatened the

whole community to which they belonged, by tempting divine wrath. It was

therefore the duty of residents to spy upon their neighbours and report any

reprehensible activities or words of theirs in order to maintain the safety and

health of all (Dickens 1959; Thompson 1965; Thomas 1971, 166 73; Aston 1984;

Hudson 1988; Rex 2002; Somerset, Havens and Pitard 2003; McSheffrey and

Tanner 2003; Ford 2006). An entirely typical and humdrum example of this,

chosen simply because it occurred in my own city of Bristol, is that of a young

widow called Margery Northoll, who was sued for breach of promise in 1539.

There were witnesses to testify to all of the key words and actions of Margery and

her jilted fiance at each of the three successive stages of their courtship, even when

they had made efforts to try to be alone. [1] It is difficult to imagine how, in such a

world, a persisting pagan religion could go completely unreported. The nearest to

any expression of one in the whole of this great mass of material is the case of two

Hertfordshire men who were accused of declaring that there were no gods but the

sun and moon. They were, however, not suggesting that these should be

worshipped, butif the charges were actually true at allfall into the category of

those who cast doubt on the efficacy of religious belief in general (National

Archives, KB9, file 40, no. 4).

Between these two substantial bodies of evidence come just two specific cases

that could be interpreted as expressions of pagan cults; but that interpretation

breaks down once they are examined in more detail. At Bexley in Kent, in 1313,

one Stephen le Pope worshipped images of gods that he had fashioned and set

up himself in his garden. On the same night that he did this, however, he also

murdered his maidservant, and it seems that we are dealing with an individual

case of lunacy (Mandy 1920 5). The second example does involve an actual cult of

a sort, at Frithelstock Priory in North Devon in 1351, where the monks established

a chapel nearby with an image in it that was supposed to represent the Virgin

Mary but which the current Bishop of Exeter thought more resembled proud and

disobedient Eve or unchaste Diana. He ordered the building and its contents to

be destroyed. Nicholas Orme has recently reconsidered the case in detail, and

concluded that the real source of the bishops wrath was that the monks had built

the chapel without asking his permission, and were using it as a source of income

by attracting pilgrims to it and adding the service of telling fortunes: pilgrims

were traditionally supposed to pray for healing or remission from sins, and not

attempt to learn their future. It may be that his particular fulmination against the

image was because the prediction of fortunes in love was one of the services

provided; although he clearly thought that monks should not be worshipping the

Virgin outside the walls of their own priory at all. The bishop concerned was

exceptional for his energy, severity and intolerance, producing a huge register of

How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants?

241

reforming and corrective orders. Once more, there is no real evidence of surviving

paganism behind the episode (Chope 1928; Orme 1992).

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

Implications for a Consideration of Medieval Christianity

It may therefore be fairly concluded that there is no good evidence for a survival of

active paganism among the English population after the early eleventh century.

That verdict may surprise few if any members of this audience, at the present time,

but it does generate the supplementary, and perhaps more interesting, question of

why this should be so. To reformulate such a question, what was there about

medieval Christianity that brought about such a swift end to pagan worship, at

least in England, and rendered any revival of it unnecessary? It may be proposed

in answer that the medieval English Christian religion was of a kind that matched

paganism in so many structural respects that it provided an entirely satisfactory

substitute for it. Let it be plain at once, in making this suggestion, that there is no

attempt involved in it to deny the novelty of the faith of Christ in many key aspects

of its nature. It offered a new theology of salvation and damnation, a new polarity

in its concept of the universe, a new relationship between deity and humanity, a

new intolerance of all other kinds of religion, and a new centralisation and

professionalisation of authority, with an equally new centrality of theological

dogma. It was in many ways a revolutionary form of human religious belief and

organisation: the point being made here was that, at a popular level, these

novelties were mediated through forms that made it seem more familiar and

acceptable in practice.

These shall now be suggested, resting on my own research for one of my books

(Hutton 1994), but also upon a range of texts that between them provide a

synthesis of recent thought upon the nature of English religion in the Middle Ages

(Thomas 1971; Rollason 1989; Duffy 1992; 2006; Brown 1995; Davies 2003; Blair

2005; Flint 2006; Phythian-Adams 2006; Burgess and Duffy 2006; Pfaff 2009). These

between them provide a reasonably good portrait of the Christianity of the period,

but the necessary comparison with paganism is difficult to make directly because

almost no evidence survives for the nature of pagan English religious practices.

What little does exist is usually interpreted by analogy with continental data

(Owen 1981; Wilson 1992; Carver, Sanmark and Semple 2010). The proposal here is

to extend that method, by comparing the body of information concerning

medieval English Christian religion, cited above, with that for ancient European

paganism as a whole. This is most abundant and well-studied in the cases of

Greece and Rome (Burkert 1985; Fox 1986; Derks 1998; Beard, North and Price

1998; Bremmer 1999; North 2000; Turcan 2000; Ando 2003; Warrior 2006; Rivers

2007; Ando 2008; Mikalson 2010; Ogden 2010). The authors of the few general

works on European paganism, however, have found many characteristics in

common between the religions of the ancient Mediterranean and those of the

north of the continent, making a framework into which the little that is known of

Anglo-Saxon pagans fits well (Jones and Pennick 1995; Dowden 2000). What is

proposed here is to compare that general framework for pagan religion with the

specific features of medieval English Christianity. When this exercise is carried

out, it becomes apparent that the new religion carried over a series of features

from the old.

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

242

Ronald Hutton

One of those was polytheism. This may at first sight appear a remarkable claim

for a system of faith that attached such importance to its worship of a single true

god, even if one divided into the Trinity. At a popular level, however, this

monotheism was much diluted by the cult of the saints, who represented the most

active centres of devotion for many, if not most, ordinary people. There were

hundreds to choose from, many of them international figures that spanned the

Christian world while others were revered only in a county or a district. Cornwall,

of course, was exceptional, with its profusion of individual parish patrons, but the

rest of England was noted for such figures as Sidwell, whose cult was confined to

Devon, and Walstan of Bawburgh, hugely popular across a single, thirty-mile,

span of Norfolk. Just as the pagan deities of the Graeco-Roman world (and

perhaps of the entire ancient world) had done, the saints of medieval England

commonly functioned as patrons and protectors of particular human activities

and aspects of the natural environment. As such, people could accord them an

intense and permanent personal devotion, but also approach them for particular

aid in times of specific need, according to their individual power and speciality.

They were variously concerned with trades, age groups, illnesses, genders,

nations, regions, farming processes or animals. Some were clearly more

overworked than others: Clement, for example, was the patron of blacksmiths,

anchor-makers, iron-workers and carpenters; and Blaise of wool-combers, waxchandlers, wild beasts and sore throats. Although their cults were usually

concentrated in parish or monastery churches, they could also be attached to

natural landmarks: commonly wells and occasionally trees. No statistics are

available for their relative popularity in medieval England, although their

absolute popularity was clearly considerable, but the situation may not have been

too different from that recorded in a rural Catholic community, the French

department of Loze`re, in the 1960s. There 5% of all working-class people

interviewed had been to mass in the previous year, but 49% of the men and 78% of

the women had visited a saints shrine (Hayden Mason, pers. comm., 13 April

1989).

The cult of saints was a steadily-developing feature of medieval English

Christianity, much more prominent in the later Anglo-Saxon Church than in the

early one, and still stronger in the high and later Middle Ages. It did, however,

both appear early and seem to be driven by popular demand, as has been

illustrated by studies of the inception of the cult of St Oswald (Lambert 2010, 208

11). It does not seem to have derived from a direct transformation of pagan deities.

In no known case was a representation of a goddess or god reused as a Christian

icon, such as happened in famous cases on the Continentsuch as those of the

Madonna and Child at Enna in Sicily, which had been cult statues of Ceres and

Proserpina, or the Virgin of Chartres Cathedral, taken from a pagan altar (Moss

and Cappanari 1982). Nor are there any apparent parallels in England to the

manner in which Irish divinities such as Brighid and Goibhniu were thought by

scholars, at least in the past, to have been refashioned as saints with the same or a

similar name (OKelly 1952; MacCana 1970, 34 5; but now also, for cautions,

Mckenna 2001; Bray 2010). There are one or two cases where buildings that have

been interpreted as Christian churches were erected on or beside recently disused

Romano-British temples, but none of these survived for long (for example,

Woodward and Leach 1993). On the other hand, not one of the medieval churches

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants?

243

or cathedrals of England has so far proved to have had an Anglo-Saxon shrine or

temple on its site (Morris 1989, 73 84). Leslie Grinsell, indeed, could trace only

twelve places in the whole of Britain where medieval Christian churches or

chapels were built near pre-Christian monuments from any period (Grinsell 1986).

This evidence flies in the face of the much-quoted letter in Bedes Ecclesiastical

History, from Pope Gregory the Great to Abbot Mellitus, written near the

beginning of the missionary effort to the English and ordering that pagan temples

should be converted to churches. For whatever reason, it does not seem to have

been obeyed. Nor is there much more sign of direct reuse of sacred waters. Those

that have yielded the most spectacular evidence of pagan votive offerings, such as

Suliss spring at Bath and Conventinas Well at Carrawburgh, Northumberland,

did not become reconsecrated as centres for Christian cults. Nor, conversely, have

traces of pagan worship been recovered at the many wells that became

prominently associated with medieval saints. Jeremy Harte has recently

confirmed in impressive detail what we had already begun to suspect: that

enthusiasm for holy wells was a phenomenon that burgeoned as the Middle Ages

wore on, rather than being a direct and straightforward transference from preChristian times (Harte 2008). The medieval English cult of saints, therefore, was

not a Christianisation of pagan deities, but a provision of new figures who offered

a parallel service. By the end of the Middle Ages, most parish churches contained

shrines dedicated to saints who were not their patrons: large urban churches could

have more than thirty of these. Many were maintained by guilds of laity who paid

a subscription to maintain a priest who would pray regularly to that saint to

intercede on their behalf, both before and after death. All but the very poorest

members of society could afford to belong to these.

A second familiar feature of ancient religion which was reproduced in medieval

Christianity was that seasonal festivals were the most important forms of ritual

observance. Services were indeed provided each Sunday, but there was no law

before the Reformation that compelled people to attend them. The events that

crowded out churches, and on which most expense and care were lavished, were

the spectacular feast days positioned at key points of the annual calendar. They

included the dawn service on Christmas Day, in a church blazing with candles and

festooned with holly and ivy; the blessing of candles at the beginning of February,

as part of a liturgy that glorified the power of light to drive back dark; the

consecration of spring foliage on Palm Sunday, and its fashioning into protective

crosses; the drama of the resurrection of Christ on Easter Day, a consecrated host

and crucifix normally being removed from a miniature tomb in which they had

been placed and guarded since Good Friday; the Rogation processions to bless

the growing crops in May; the processions that celebrated Pentecost, with the

releasing of a white dove from the ceiling to symbolise the Holy Ghost; and

the prayers for the dead and ringing of bells to comfort them at the feasts of All

Saints and All Souls that ushered in the dark and dead time of the year. For most of

the time, the church was regarded as a house of the deity, in which a priest or

priests kept regular worship going without the need of a congregation; although

the personally devout, and those in need, were of course welcome. This seems

very much to have been the pagan pattern.

The Christianisation of pagan festivals was a much more regular and frequent

occurrence than the Christianisation of pagan places and deities, but it was not a

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

244

Ronald Hutton

wholesale and automatic one. The solstices certainly became the feasts of the

Nativity and of John the Baptist, while the quarter day that opened winter was

appropriated for All Saints. Some of these developments took some time,

however: the institution of the feast of All Saints only began in the ninth century.

The greatest of all Christian festivals, Easter, was tied not to any pagan celebration

but to the Hebrew Passover, and overshadowed the pagan feast of May Day so

much that the latter was only given to two minor apostles. The traditional quarter

day that opened spring only became significant in church liturgy because it

(almost) coincided with the major Christian event of the Purification of the Virgin

Mary, and Christs recognition as a saviour of the Gentiles. What happened overall

was that seasonal themes were interwoven at festivals with key messages and

passages from the New Testament, to express both to maximum effect. It was an

appropriation of traditional ways as much as an adaptation to them. For centuries

the English Church maintained a distance, often disapproving, from secular

revelry such as May games, village summer feasts, the crowning of mock

monarchs to preside over seasonal celebration, and collections by ploughmen in

January. In the late medieval period, however, it incorporated these as well, by

converting them into mechanisms to raise money for the upkeep of religious

buildings and ceremonies. Parish officers would organise seasonal celebrations,

with traditional pastimes and entertainments, to which parishioners paid

admission, and the profits were put towards the expenses of their church. In

rural communities, in particular, these became the normal means of providing

repairs and embellishments for the building and its decorations, and the trappings

and commodities of services. They completely removed the need to levy a rate,

and, by turning activities formerly associated with temptation to sin into a means

of glorifying heavenly powers, arguably cheated the Devil.

Medieval English Christianity also resembled the older religions in the space

that it provided for women. Divine female figures were amply represented by

saints, and above all by the Virgin Mary herself, who made an effective queen of

heaven. Human women had their own religious houses, in the form of nunneries,

and featured as celebrated mystics, such as Lady Julian of Norwich. They

sometimes served as churchwardens, and were admitted to most parish gilds on

an equal basis with men, and served as officials in them, while some gilds were

reserved entirely for women. All this had the effect of erecting a thick screen

before the apparently unequivocal maleness of the single true deity. A fourth

major continuity with the old ways was that the central religious rite was sacrifice:

that of the mass, offered up at an altar as the old animal sacrifices had been. The

major empowering motivation of paganism, the propitiation of deities with gifts,

had been succeeded by one in which the deity offered himself as the sacrificial

being, a concept that the evolving doctrine of transubstantiation made vividly real.

The lesser sacrifices offered by paganism, of incense and flowers, remained in

churches as accessories to ritual. Preaching, a distinctive Christian contribution to

the religious mainstream, remained popular through the Middle Ages, being

especially carried on by friars in the later centuries. It was not, however, essential

to the practice of the religion, as the consecration and communion of the mass was.

In general, parish priests were not expected to preach, and their essential role was

to carry out rites for the good of the community in the manner of pagan priests and

priestesses before them.

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants?

245

In this context, it becomes important to emphasise how much the Protestant

Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation had in common as reform

movements directed at medieval Christianity, and especially at its popular

manifestations. In many key respects they were utterly different, and bitterly

opposed, forms of religion, but both were designed to achieve a better control over

general religious observance, with a greatly enhanced level of education,

uniformity and active lay piety. This is where the insights of historians such as

Jean Delumeau deserve a fresh consideration, and respect: as they argued, the

Christianity of early modern Western Europe was indeed radically different from

that of the Middle Ages. It did represent a fresh and strenuous attempt to inculcate

at a popular level what devout churchmen had always held to be the key tenets of

Christianity, and in the process to remove many elements from the practice of

religion that perpetuated or resembled pagan forms. The transition was especially

intense in a Protestant nation of the kind that England became, where it involved

the abolition of the mass, the cult of the saints, and the seasonal rituals, and the

substitution of a religion based on preaching, compulsory Sunday attendance and

a far more male-centred concept of the divine order. The crucial distinction to be

drawn here is that this process did not represent the definitive conversion of the

populace to the Christian faith, as authors such as Delumeau suggested, but the

replacement of one form of Christianity with another.

It may, further, be suggested that the new form was a more difficult one for

ordinary people to maintain, and most problematic was its concept that salvation

was a vigorous and strenuous personal matter. English Protestant preachers in the

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries repeatedly complained of the disposition of

their congregations to regard an unremitting preoccupation with salvation as the

business of the professional ministry. For themselves, they were inclined to believe

that fairly regular church attendance, especially with communion at the major

festivals, and general good behaviour towards their neighbours was sufficient for

their entry into heaven (Collinson 1982; 1988; Haigh 1993). Certainly, the

Reformation experiment proved a failure in one essential respect: that of inducing

a much greater piety and uniformity among ordinary people. Instead it resulted

first in a far greater diversity of opinion and thenin just over a centuryin the

complete breakdown of compulsory church attendance and the beginning of a

long process of secularisation in state and society. Even so, it may be proposed that

the religious attitudes of the English in the late twentieth century were in some

respects more similar to those of their medieval predecessors than those which

Tudor and Stuart churchmen had attempted to inculcate. A modern society in

which most people did not regularly attend religious services, but many of these

still desired the services of a priestly figure for personal rites of passage and in

which parish churches filled up at Christmas, has certain obvious older parallels.

They are embodied in surveys in 1985, in which only 10% of respondents still

attended any church but 65% still confidently described themselves as Christian,

and 1990, in which 32% believed in a personal god but 71% believed in a being

called God. They are arguably summed up by the famous answer of a Londoner

in 1968, who, asked if she or he believed in a god who changed the course of events

on earth, replied confidently: No, just the ordinary one (Abrams, Gerard and

Timms 1985, 60; Davie 1994, 1 and 74 92). We may be on the brink here of a

general theory of religious behaviour on the part of the people of this land,

246

Ronald Hutton

spanning more than two thousand years: but that has taken me very far from my

original question, and so I shall conclude my considerations of it now, with further

gratitude for the honour of addressing this company.

Note

[1] Bristol Record Office, D/D/Cd 4, 1535-40. I owe this reference to my former colleague at Bristol,

Joseph Bettey.

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

References Cited

Abrams, Mark, David Gerard, and Noel Timms, eds. Values and Social Change in Britain. London:

Macmillan, 1985.

Andersen, Jorgen. The Witch on the Wall: Medieval Erotic Sculpture in the British Isles. Copenhagen:

Rosenkilde and Bogger, 1977.

Ando, Clifford, ed. Roman Religion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003.

. The Matter of The Gods. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

Aston, Margaret. Lollards and Reformers. London: Hambledon, 1984.

Basford, Kathleen. The Green Man. Ipswich: Brewer, 1978.

Beard, Mary, John North, and Simon Price. Religions of Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1998.

Blair, John. The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Bray, Dorothy Ann. Irelands Other Apostle: Cogitosuss St Brigit. Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies

59 (2010): 55 70.

Bremmer, Jan D. Greek Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Brown, Andrew D. Popular Piety in Late Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Burgess, Clive, and Noel Duffy, eds. The Parish in Medieval England. Donington: Tyas, 2006.

Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Oxford: Blackwell, 1985.

Carver, Martin, Alex Sanmark, and Sarah Semple, eds. Signals of Belief in Early England. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2010.

Centerwall, Brandon S. The Name of the Green Man. Folklore 108 (1997): 25 33.

Chope, R. P. Frithelstock Prior. Transactions of the Devonshire Association 61 (1928): 175 6.

Clark, G. N. The Seventeenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1945.

Collinson, Patrick. The Religion of Protestants. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982.

. The Birthpangs of Protestant England. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988.

Commissioners of Public Works. Ancient Laws and Institutes of England. London: Commissioners of

Public Works, 1840.

Coulton, Geoffrey. Five Centuries of Religion. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1925.

Davie, Grace. Religion in Britain Since 1945. Oxford: Blackwell, 1994.

Davies, Richard. The Church. In The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, ed. Ralph Griffiths. 87 116.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Delumeau, Jean. Catholicism entre Luther et Voltaire. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1971.

How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants?

247

Derks, Tom. Gods, Temples and Ritual Practices. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1998.

Dickens, A. G. Lollards and Protestants in the Diocese of York 1509 1558. Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1959.

Dowden, Ken. European Paganism. London: Routledge, 2000.

Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 1992.

. Religious Belief. In A Social History of England, 1200 1500, eds. Rosemary Horrox, and W.

Mark Ormrod. 293 339. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Flint, Valerie. A Magical Universe. In A Social History of England, 12001500, eds. Rosemary

Horrox, and W. Mark Ormrod. 340 55. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

Ford, Judy Ann. John Mirks Festial: Orthodoxy, Lollardy and the Common People in Fourteenth-Century

England. Cambridge: Brewer, 2006.

Fox, Robin Lane. Pagans and Christians. London: Viking, 1986.

Gee, Henry, and William John Hardy, eds. Documents Illustrative of English Church History. London:

1896.

Grinsell, Leslie. The Christianization of Prehistoric and Other Pagan Sites. Landscape History 8

(1986): 27 37.

Haddan, Arthur West, and William Stubbs, eds. Councils and Ecclesiastical Documents Relating to Great

Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1871.

Haigh, Christopher. English Reformations. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Harte, Jeremy. English Holy Wells. Wymeswold: Heart of Albion, 2008.

Hayman, Richard. Green Men and the Way of All Flesh. British Archaeology 100 (2008): 12 17.

. Ballad of the Green Man. History Today 60, no. 4 (2010): 37 44.

Hill, Christopher. Reformation to Industrial Revolution. London: Weidenfeld, 1967.

Hudson, Anne. The Premature Reformation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Hutton, Ronald. The Rise and Fall of Merry England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

. The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1998.

. Astral Magic: The Acceptable Face of Paganism. In Patrick Curry and Michael York, ed.

Nicholas Campion. 10 24. Bristol: Cinnabar Books, 2004.

Johnson, John, ed. A Collection of the Laws and Canons of the Church of England. Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 1850.

Jones, Prudence, and Nigel Pennick. A History of Pagan Europe. London: Routledge, 1995.

Judge, Roy. The Jack-in-the-Green. London: Folklore Society, 1979.

Karkov, Catherine. Sheela-na-gigs and Other Unruly Women. In From Ireland Coming, ed. Colum

Hourihane. 313 31. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Kelly, Eamonn. Sheela-na-gigs in the National Museum of Ireland. In Irish Antiquities, ed. Michael

Ryan. 173 84. Bray: Wordwell, 1992.

. Irish Sheela-na-gigs and Related Figures. In Medieval Obscenities, ed. Nicola McDonald.

124 37. York: York Medieval Press, 2006.

Lambert, Malcolm. Christians and Pagans: The Conversion of Britain from Alban to Bede. London: Yale

University Press, 2010.

MacCana, Proinsias. Celtic Mythology. London: Hamlyn, 1970.

248

Ronald Hutton

MacDermott, Mercia. Explore Green Men. Wymeswold: Heart of Albion, 2003.

Mandy, W. H. An Incident at Bexley. Woolwich and District Antiquarian Society Annual Report and

Transactions 23 (1920 5): 25 37.

Mckenna, Catherine. Apotheosis and Evanescence: The Fortunes of St Brigit in the Nineteenth and

Twentieth Centuries. In The Individual in Celtic Literatures, ed. Joseph Falaky Nagy. 74 108.

Dublin: Four Courts, 2001.

McSheffrey, Shannon, and Norman Tanner, eds. Lollards of Coventry 5th series 23. Cambridge:

Camden Society, 2003.

Mikalson, Jon D. Ancient Greek Religion. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Milis, Ludo, ed. De heidense Middeleeuwen. Brussels: Brepols, 1991. English translation: The Pagan

Middle Ages. Woodbridge: Boydell, 1998.

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

Morris, Richard. Churches in the Landscape. London: Dent, 1989.

Moss, Leonard W., and Stephen C. Cappanari. In Quest of the Black Virgin. In Mother Worship, ed.

James J. Preston. 53 74. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982.

Murray, Margaret. Female Fertility Figures. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 64 (1934):

93 100.

North, J. A. Roman Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Ogden, Daniel, ed. A Companion to Greek Religion. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

OKelly, Michael J. St Gobnets House, Ballyvourney. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological

Society 57 (1952): 18 40.

Orme, Nicholas. Bishop Grandisson and Popular Religion. Transactions of the Devonshire Association

124 (1992): 107 18.

Owen, Gale R. Rites and Religions of the Anglo-Saxons. Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1981.

Pfaff, Richard William. The Liturgy in Medieval England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

2009.

Phythian-Adams, Charles. Ritual Constructions of Society. In A Social History of England, 1200

1500, eds. Rosemary Horrox, and W. Mark Ormrod. 369 82. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2006.

Raglan, Lady. The Green Man in Church Architecture. Folklore 50 (1939): 45 57.

Rex, Richard. The Lollards. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002.

Rivers, James B. Religion in the Roman Empire. Oxford: Blackwell, 2007.

Rollason, David. Saints and Relics in Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell, 1989.

Ross, Anne. The Divine Hag of the Pagan Celts. In The Divine Hag of the Pagan Celts, ed. Venetia

Newall. 13964. London: Routledge, 1973.

Runciman, Stephen. Preface to Margaret Murray, The Witch Cult in Western Europe. Paperback imprint.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962.

Sheridan, Ronald, and Anne Ross. Grotesques and Gargoyles: Paganism in the Medieval Church. Newton

Abbot: David and Charles, 1975.

Somerset, Fiona, Jill C. Havens, and Derek Pitard. Lollards and their Influence in Late Medieval England.

Woodbridge: Boydell, 2003.

Thomas, Keith. Religion and the Decline of Magic. London: Weidenfeld, 1971.

Thompson, John A. F. The Later Lollards. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1965.

How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants?

249

Thurlby, Malcolm. The Herefordshire School of Romanesque Sculpture. Almeley: Logaston, 1999.

Turcan, Robert. The Gods of Ancient Rome. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2000.

Warrior, Valerie. Roman Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Weir, Anthony, and James Jerman. Images of Lust: Sexual Carvings on Medieval Churches. London:

Batsford, 1986.

Whitelock, D., M. Brett, and C. N. L. Brooke. Councils and Synods, with Other Documents Relating to the

English Church. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981.

Wilson, David. Anglo-Saxon Paganism. London: Routledge, 1992.

Wood, Rita. Before the Green Man. Medieval Life 14 (2000): 8 13.

Downloaded by [151.229.70.218] at 06:27 28 October 2015

Woodward, Anne, and Peter Leach. The Uley Shrines. London: English Heritage, 1993.

Biographical Note

Ronald Hutton is Professor of History at Bristol University, and the author of fourteen

books and scores of essays, covering a wide range of historical topics, mainly but not

exclusively in Britain. He is at present writing a survey of the current evidence for the

nature of pre-Christian religious belief and practice entitled Britains Pagan Heritage.

You might also like

- The Birth of Popular Heresy A Millennial Phenomenon, R. I. MOOREDocument18 pagesThe Birth of Popular Heresy A Millennial Phenomenon, R. I. MOOREjiorgosNo ratings yet

- Tales from the Lands of Nuts and Grapes (Spanish and Portuguese Folklore)From EverandTales from the Lands of Nuts and Grapes (Spanish and Portuguese Folklore)No ratings yet

- Royston Cave's Pagan Carvings and Knights Templar ConnectionDocument10 pagesRoyston Cave's Pagan Carvings and Knights Templar ConnectionVarious TingsNo ratings yet

- The Fool and The TricksterDocument2 pagesThe Fool and The TricksterFakmiKristNo ratings yet

- Inquiry about Bacchanalia and Night Rites (quaestio de Bacchanalibus sacrisque nocturnis) A staged operation for political purposesFrom EverandInquiry about Bacchanalia and Night Rites (quaestio de Bacchanalibus sacrisque nocturnis) A staged operation for political purposesNo ratings yet

- The Goddess and The Great Rite Hindu Tan-60229287Document22 pagesThe Goddess and The Great Rite Hindu Tan-60229287Mike LeeNo ratings yet

- The Bride of Christ Goes to Hell: Metaphor and Embodiment in the Lives of Pious Women, 200-1500From EverandThe Bride of Christ Goes to Hell: Metaphor and Embodiment in the Lives of Pious Women, 200-1500No ratings yet

- Review of The White Goddess by Robert GRDocument5 pagesReview of The White Goddess by Robert GRÍtalo CoutinhoNo ratings yet

- Beyond Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges: Essays in Honour of Brian SpencerFrom EverandBeyond Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges: Essays in Honour of Brian SpencerRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Dea Brigantia - Nora H JolliffeDocument33 pagesDea Brigantia - Nora H JolliffeIsmael WolfNo ratings yet

- Masonic Arts at Guildford CathedralDocument7 pagesMasonic Arts at Guildford CathedralVarious TingsNo ratings yet

- Tales of Sacred Wells in Ireland (Folklore History Series)From EverandTales of Sacred Wells in Ireland (Folklore History Series)No ratings yet

- The Enigma of Desire Salvador Dali and The Conquest of The Irrational Libre PDFDocument16 pagesThe Enigma of Desire Salvador Dali and The Conquest of The Irrational Libre PDFΧάρης ΦραντζικινάκηςNo ratings yet

- The Role of Religion and Divinity in the Middle Ages - History Book Best Sellers | Children's HistoryFrom EverandThe Role of Religion and Divinity in the Middle Ages - History Book Best Sellers | Children's HistoryNo ratings yet

- A Weed in The Corn Surrender and RegrantDocument55 pagesA Weed in The Corn Surrender and RegrantGary LongshaweNo ratings yet

- The Manly Priest: Clerical Celibacy, Masculinity, and Reform in England and Normandy, 166-13From EverandThe Manly Priest: Clerical Celibacy, Masculinity, and Reform in England and Normandy, 166-13No ratings yet

- The Historicty and Historicisation of ArthurDocument33 pagesThe Historicty and Historicisation of ArthurStephen MurtaughNo ratings yet

- More Celtic Elements in Gawain and The Green KnightDocument37 pagesMore Celtic Elements in Gawain and The Green Knightmichelez6No ratings yet

- Woman under Monasticism: Chapters on Saint-Lore and Convent Life between A.D. 500 and A.D. 1500From EverandWoman under Monasticism: Chapters on Saint-Lore and Convent Life between A.D. 500 and A.D. 1500No ratings yet

- A Dionysian Ritual, Mystis in Nonnus' DionysiacaDocument18 pagesA Dionysian Ritual, Mystis in Nonnus' DionysiacaRosa GgvNo ratings yet

- Y - Cymmrodor 8Document280 pagesY - Cymmrodor 8zrjaymanNo ratings yet

- Byhelenfulton: Matthew Arnold and The Canon of Medieval Welsh LiteratureDocument21 pagesByhelenfulton: Matthew Arnold and The Canon of Medieval Welsh LiteratureNinou NinouNo ratings yet

- Hale John MichellDocument21 pagesHale John MichellrichardrudgleyNo ratings yet

- Writing The History of Witchcraft: A Personal View: R.hutton@bristol - Ac.ukDocument24 pagesWriting The History of Witchcraft: A Personal View: R.hutton@bristol - Ac.ukPatrick SchwarzNo ratings yet

- Le Morte D ArhturDocument15 pagesLe Morte D ArhturKarl Michael RubinNo ratings yet

- Five Stages of Greek ReligionDocument204 pagesFive Stages of Greek Religionedgarlog100% (3)

- Cunning Men AllenDocument18 pagesCunning Men AllenFrancesco VinciguerraNo ratings yet

- Fulton Uses of The Vernacular in Med WalesDocument25 pagesFulton Uses of The Vernacular in Med WalesMarina AssaNo ratings yet

- Ireland's History RevealedDocument351 pagesIreland's History Revealedforumb100% (1)

- 20140969Document27 pages20140969Anton_Toth_5703No ratings yet

- Dionysus and Kataragama: A Study of Parallel Mystery CultsDocument25 pagesDionysus and Kataragama: A Study of Parallel Mystery Cultsjorge matoNo ratings yet

- Balafrej AO Pisa Griffin 2012Document14 pagesBalafrej AO Pisa Griffin 2012lamiabaNo ratings yet

- Madness and Character Development in Medieval Arthurian TalesDocument10 pagesMadness and Character Development in Medieval Arthurian TalesManol GlishevNo ratings yet

- The Practice of Irish Kingship in The Central Middle AgesDocument335 pagesThe Practice of Irish Kingship in The Central Middle Agesoldenglishblog100% (1)

- Nymue, The Chief Lady of The Lake, in Malory's Le Morte DarthurDocument18 pagesNymue, The Chief Lady of The Lake, in Malory's Le Morte Darthurbluesapphire18No ratings yet

- Dramatic Form and Philosophical Content in Plato's Dialogues Arthur A. Krentz PDFDocument17 pagesDramatic Form and Philosophical Content in Plato's Dialogues Arthur A. Krentz PDFhuseyinNo ratings yet

- The Roman Empire Through its Art and ArtefactsDocument46 pagesThe Roman Empire Through its Art and ArtefactsCol O'neilNo ratings yet

- Norse Revival Transformations of German Neopaganism PDFDocument430 pagesNorse Revival Transformations of German Neopaganism PDFTóth AndrásNo ratings yet

- Digitized reproduction of a rare Welsh botany book from 1813Document303 pagesDigitized reproduction of a rare Welsh botany book from 1813avallonia9No ratings yet

- Wisdom Literature in Early IrelandDocument34 pagesWisdom Literature in Early Irelandoldenglishblog100% (1)

- 9781909646728Document384 pages9781909646728Šime DemoNo ratings yet

- King Arthur in Irish Pseudo Historical TDocument150 pagesKing Arthur in Irish Pseudo Historical Tagxz100% (1)

- Welsh Middle AgeDocument33 pagesWelsh Middle AgeNataliiaCamargoNo ratings yet

- On the Burial of Unchaste Vestal VirginsDocument15 pagesOn the Burial of Unchaste Vestal VirginsRaicea IonutNo ratings yet

- M, R & S Elements of Shamanism: YTH Itual THE AcredDocument4 pagesM, R & S Elements of Shamanism: YTH Itual THE AcredSeth Brogdon100% (1)

- Chronicle LanercostDocument412 pagesChronicle Lanercostmartin100% (1)

- University of Tartu hosts 6th Nordic-Celtic-Baltic Folklore SymposiumDocument104 pagesUniversity of Tartu hosts 6th Nordic-Celtic-Baltic Folklore SymposiumBia GunnerNo ratings yet

- Thelemic Symposium 2009 (Review)Document2 pagesThelemic Symposium 2009 (Review)Mogg Morgan0% (1)

- On Being A Pagan - Alain de BenoistDocument14 pagesOn Being A Pagan - Alain de BenoistbenignhypocNo ratings yet

- (-) Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones-Aphrodite's Tortoise - The Veiled Woman of Ancient Greece-The Classical Press of Wales (2003) PDFDocument368 pages(-) Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones-Aphrodite's Tortoise - The Veiled Woman of Ancient Greece-The Classical Press of Wales (2003) PDFEthos100% (2)

- An Enigmatic Indo-European Rite Paederas PDFDocument20 pagesAn Enigmatic Indo-European Rite Paederas PDFEthosNo ratings yet

- Understanding Ancient Greek Animal SacrificeDocument11 pagesUnderstanding Ancient Greek Animal SacrificeANY1NEXT100% (1)

- A Gaelic Eschatological Folktale Celtic PDFDocument25 pagesA Gaelic Eschatological Folktale Celtic PDFTrinidad Farías PiñeiroNo ratings yet

- Dionysian Lines of Flight Becoming Animal by Peter Mark AdamsDocument10 pagesDionysian Lines of Flight Becoming Animal by Peter Mark AdamsPeter Mark Adams100% (1)

- James VI and I and WitchcraftDocument2 pagesJames VI and I and Witchcraftmoro206hNo ratings yet

- Marcelo FicinoDocument7 pagesMarcelo Ficinovojkan121No ratings yet

- Ecofeminist Philosophy © Rita D. Sherma © Care - GtuDocument6 pagesEcofeminist Philosophy © Rita D. Sherma © Care - GtuKath GloverNo ratings yet

- Colonization and HousewifizationDocument19 pagesColonization and HousewifizationMariana PennaNo ratings yet

- The Pain in Frida Kahlo's ArtDocument131 pagesThe Pain in Frida Kahlo's ArtestragoNo ratings yet

- WN ArtisanDocument18 pagesWN ArtisanKath GloverNo ratings yet

- The Transmission of Transition2 WHDKTX 1Document16 pagesThe Transmission of Transition2 WHDKTX 1Kath GloverNo ratings yet

- Pan Pastel Color ChartDocument1 pagePan Pastel Color ChartKath GloverNo ratings yet

- LDB Gender (Sex)Document474 pagesLDB Gender (Sex)Kath GloverNo ratings yet

- House of GarsendaDocument1 pageHouse of GarsendaKath Glover0% (1)

- Ecofeminist Philosophy © Rita D. Sherma © Care - GtuDocument6 pagesEcofeminist Philosophy © Rita D. Sherma © Care - GtuKath GloverNo ratings yet

- Casualty Simulation TechniquesDocument61 pagesCasualty Simulation TechniquesKath Glover100% (1)

- Bismuth Chemistry RangeDocument2 pagesBismuth Chemistry RangeKath GloverNo ratings yet

- DR Georgian Oil Broadsheet (PRINT) PDFDocument2 pagesDR Georgian Oil Broadsheet (PRINT) PDFKath GloverNo ratings yet

- Liquitex Color Chart Heavy BodyDocument2 pagesLiquitex Color Chart Heavy BodyaleNo ratings yet

- CRYLA Technical HandbookDocument19 pagesCRYLA Technical HandbookKath GloverNo ratings yet

- Colour Chart Van Gogh Water Colour: PY154/PO62 Pigments Used Degree of LightfastnessDocument1 pageColour Chart Van Gogh Water Colour: PY154/PO62 Pigments Used Degree of LightfastnessThiagoDuarteNo ratings yet

- Lukas Cry L StudioDocument2 pagesLukas Cry L StudioKath GloverNo ratings yet

- Akua CatalogDocument8 pagesAkua CatalogKath GloverNo ratings yet

- DR Watersoluble Block Ink Colour ChartDocument1 pageDR Watersoluble Block Ink Colour ChartKath GloverNo ratings yet

- Akua User GuideDocument24 pagesAkua User GuideKath GloverNo ratings yet

- Caligo ReliefDocument2 pagesCaligo ReliefKath GloverNo ratings yet

- GoldenA Z14Document16 pagesGoldenA Z14Kath Glover50% (2)

- Aham Watercolor Color-Charts Final Web-SmDocument1 pageAham Watercolor Color-Charts Final Web-SmKath GloverNo ratings yet

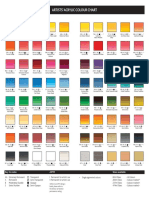

- Artists' Acrylic Colour Chart: Key To Codes Astm Sizes AvailableDocument1 pageArtists' Acrylic Colour Chart: Key To Codes Astm Sizes AvailableKath GloverNo ratings yet

- ShinHan PWC Colour ChartDocument1 pageShinHan PWC Colour ChartKath GloverNo ratings yet

- Aquafine Gouache Colour ChartDocument1 pageAquafine Gouache Colour ChartKath GloverNo ratings yet

- Chiro Guidelines WHODocument51 pagesChiro Guidelines WHOMinh MinhNo ratings yet

- FP AquarelleFine 2016-07-08 enDocument2 pagesFP AquarelleFine 2016-07-08 enKath GloverNo ratings yet

- W & N Product DownloadDocument13 pagesW & N Product DownloadKim DolanNo ratings yet

- Liquitex color matching across mediumsDocument2 pagesLiquitex color matching across mediumsKoula IslayNo ratings yet

- Lancashire Funeral CertificatesDocument133 pagesLancashire Funeral CertificatesKath GloverNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 HandoutDocument18 pagesChapter 10 HandoutChad FerninNo ratings yet

- Aiatsoymeo2016t06 SolutionDocument29 pagesAiatsoymeo2016t06 Solutionsanthosh7kumar-24No ratings yet

- Silvianita - LK 0.1 Modul 2 English For Personal CommunicationDocument3 pagesSilvianita - LK 0.1 Modul 2 English For Personal CommunicationSilvianita RetnaningtyasNo ratings yet

- Bob Jones - Science 4Document254 pagesBob Jones - Science 4kage_urufu100% (4)

- 7 Years - Lukas Graham SBJDocument2 pages7 Years - Lukas Graham SBJScowshNo ratings yet

- CSEC Notes US in The CaribbeanDocument8 pagesCSEC Notes US in The Caribbeanvernon white100% (2)

- APCHG 2019 ProceedingsDocument69 pagesAPCHG 2019 ProceedingsEnrico SocoNo ratings yet

- 2200SRM0724 (04 2005) Us en PDFDocument98 pages2200SRM0724 (04 2005) Us en PDFMayerson AlmaoNo ratings yet

- My Perspective On Ayurveda-ArticleDocument2 pagesMy Perspective On Ayurveda-ArticleAaryan ParashuramiNo ratings yet

- Network Monitoring With Zabbix - HowtoForge - Linux Howtos and TutorialsDocument12 pagesNetwork Monitoring With Zabbix - HowtoForge - Linux Howtos and TutorialsShawn BoltonNo ratings yet

- Wjec Gcse English Literature Coursework Mark SchemeDocument6 pagesWjec Gcse English Literature Coursework Mark Schemef6a5mww8100% (2)

- Discuss in Details With Appropriate Examples What Factors Could Lead To Sympatric and Allopatric SpeciationDocument5 pagesDiscuss in Details With Appropriate Examples What Factors Could Lead To Sympatric and Allopatric SpeciationKhairul ShahmiNo ratings yet

- Modern Mathematical Statistics With Applications (2nd Edition)Document13 pagesModern Mathematical Statistics With Applications (2nd Edition)Alex Bond11% (28)

- Three Phase Transformer Model For TransientsDocument10 pagesThree Phase Transformer Model For TransientsYeissonSanabriaNo ratings yet

- Financial MarketsDocument323 pagesFinancial MarketsSetu Ahuja100% (2)

- Liquid Hydrogen As A Propulsion Fuel, 1945-1959Document341 pagesLiquid Hydrogen As A Propulsion Fuel, 1945-1959Bob AndrepontNo ratings yet

- EY The Cfo Perspective at A Glance Profit or LoseDocument2 pagesEY The Cfo Perspective at A Glance Profit or LoseAayushi AroraNo ratings yet

- Lived Experiences of Elementary Teachers in A Remote School in Samar, PhilippinesDocument14 pagesLived Experiences of Elementary Teachers in A Remote School in Samar, Philippinesルイス ジャンNo ratings yet

- Narasimha EngDocument33 pagesNarasimha EngSachin SinghNo ratings yet

- Femap-58 Volume2 508Document357 pagesFemap-58 Volume2 508vicvic ortegaNo ratings yet

- CHEST 6. Chest Trauma 2022 YismawDocument61 pagesCHEST 6. Chest Trauma 2022 YismawrobelNo ratings yet

- Dreams and Destiny Adventure HookDocument5 pagesDreams and Destiny Adventure HookgravediggeresNo ratings yet

- Discrete Mathematics - Logical EquivalenceDocument9 pagesDiscrete Mathematics - Logical EquivalenceEisha IslamNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Perspectives Through the AgesDocument13 pagesPhilosophical Perspectives Through the Agesshashankmay18No ratings yet

- Operations Management 2Document15 pagesOperations Management 2karunakar vNo ratings yet

- Blind and Visually ImpairedDocument5 pagesBlind and Visually ImpairedPrem KumarNo ratings yet

- Intro To Flight (Modelling) PDFDocument62 pagesIntro To Flight (Modelling) PDFVinoth NagarajNo ratings yet

- INTERNSHIP REPORT 3 PagesDocument4 pagesINTERNSHIP REPORT 3 Pagesali333444No ratings yet

- Week 1 Amanda CeresaDocument2 pagesWeek 1 Amanda CeresaAmanda CeresaNo ratings yet

- Fuzzys CodesDocument39 pagesFuzzys CodesJak JakNo ratings yet

- The Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined AmericaFrom EverandThe Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined AmericaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziFrom EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (157)

- Hubris: The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth CenturyFrom EverandHubris: The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth CenturyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- The Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushFrom EverandThe Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Future of Capitalism: Facing the New AnxietiesFrom EverandThe Future of Capitalism: Facing the New AnxietiesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Digital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires Trying to Reinvent MoneyFrom EverandDigital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires Trying to Reinvent MoneyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (51)

- Dunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion PictureFrom EverandDunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion PictureRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- The Lost Peace: Leadership in a Time of Horror and Hope, 1945–1953From EverandThe Lost Peace: Leadership in a Time of Horror and Hope, 1945–1953No ratings yet

- We Crossed a Bridge and It Trembled: Voices from SyriaFrom EverandWe Crossed a Bridge and It Trembled: Voices from SyriaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- The Rape of Nanking: The History and Legacy of the Notorious Massacre during the Second Sino-Japanese WarFrom EverandThe Rape of Nanking: The History and Legacy of the Notorious Massacre during the Second Sino-Japanese WarRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (63)

- Rebel in the Ranks: Martin Luther, the Reformation, and the Conflicts That Continue to Shape Our WorldFrom EverandRebel in the Ranks: Martin Luther, the Reformation, and the Conflicts That Continue to Shape Our WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Desperate Sons: Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, John Hancock, and the Secret Bands of Radicals Who Led the Colonies to WarFrom EverandDesperate Sons: Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, John Hancock, and the Secret Bands of Radicals Who Led the Colonies to WarRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Kleptopia: How Dirty Money Is Conquering the WorldFrom EverandKleptopia: How Dirty Money Is Conquering the WorldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (25)

- The Great Fire: One American's Mission to Rescue Victims of the 20th Century's First GenocideFrom EverandThe Great Fire: One American's Mission to Rescue Victims of the 20th Century's First GenocideNo ratings yet

- 1963: The Year of the Revolution: How Youth Changed the World with Music, Fashion, and ArtFrom Everand1963: The Year of the Revolution: How Youth Changed the World with Music, Fashion, and ArtRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Reagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarFrom EverandReagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Witness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul IIFrom EverandWitness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul IIRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)

- Project MK-Ultra: The History of the CIA’s Controversial Human Experimentation ProgramFrom EverandProject MK-Ultra: The History of the CIA’s Controversial Human Experimentation ProgramRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- Never Surrender: Winston Churchill and Britain's Decision to Fight Nazi Germany in the Fateful Summer of 1940From EverandNever Surrender: Winston Churchill and Britain's Decision to Fight Nazi Germany in the Fateful Summer of 1940Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (45)

- Diana Mosley: Mitford Beauty, British Fascist, Hitler's AngelFrom EverandDiana Mosley: Mitford Beauty, British Fascist, Hitler's AngelRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (47)

- D-Day: June 6, 1944 -- The Climactic Battle of WWIIFrom EverandD-Day: June 6, 1944 -- The Climactic Battle of WWIIRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (36)

- Cry from the Deep: The Sinking of the KurskFrom EverandCry from the Deep: The Sinking of the KurskRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- Knowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge: From Ancient Wisdom to Modern MagicFrom EverandKnowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge: From Ancient Wisdom to Modern MagicRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (25)

- They All Love Jack: Busting the RipperFrom EverandThey All Love Jack: Busting the RipperRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (30)

- Voyagers of the Titanic: Passengers, Sailors, Shipbuilders, Aristocrats, and the Worlds They Came FromFrom EverandVoyagers of the Titanic: Passengers, Sailors, Shipbuilders, Aristocrats, and the Worlds They Came FromRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (86)

- Voyagers of the Titanic: Passengers, Sailors, Shipbuilders, Aristocrats, and the Worlds They Came FromFrom EverandVoyagers of the Titanic: Passengers, Sailors, Shipbuilders, Aristocrats, and the Worlds They Came FromRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (99)

- The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and PowerFrom EverandThe Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and PowerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (47)