Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tahapan Karir Super

Uploaded by

Widyatmiko Adhi PradanaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tahapan Karir Super

Uploaded by

Widyatmiko Adhi PradanaCopyright:

Available Formats

JOURNAL OF VOCATIONAL BEHAVIOR

ARTICLE NO.

51, 358374 (1997)

VB961544

Supers Career Stages and the Decision to

Change Careers

Roslyn Smart and Candida Peterson

The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

This study examined Supers (1990) concept of recycling through the stages of

adult career development in a sample of 226 Australian men and women who were

approximately evenly distributed across the following four steps in the uptake of a

second career: (a) contemplating a change, (b) choosing a new field, (c) implementing

a change, and (d) change fully completed. A group of adults of similar age, gender,

education, occupation, and career history who had no intention of switching careers

was also included for comparison. Recycling predictions were supported by the finding

that the three groups who were in the throes of career change displayed greater concern

with Supers first (exploration) stage than the nonchanging control group. In addition,

the two groups who were most intensely involved in the change process (choosing

field and implementing) scored higher in exploration concern than the group whose

career change was fully completed. Satisfaction also varied as a function of the

participants stage in the process of switching to a new career. Global satisfaction

with the present job was highest in workers who had completed the change to a new

career, but nonchangers were more satisfied than the three groups who were actively

caught up in the change process. On the other hand, satisfaction with the overall

pattern of career development was higher in the two stable groups (nonchangers and

change-completed) than among the three groups still actively involved in making a

change. Implications of these results for midlife career counseling were considered.

q 1997 Academic Press

Most stage theories of psychological development posit a set of largely

irreversible changes that follow one another in rigid order that is tightly linked

to chronological age (Kohlberg, 1969). However, one of the most influential

theories of adult career development (Super, 1990) departs from this approach

in two key respects. In his recent writings, Super has continued to rely upon

the concept he pioneered in the 1950s (Super, 1953, 1957) of career stages

as clusters of distinctive attitudes, motivations, and behaviors that arise in

sequence over development (Salomone, 1996). But his present model (1990)

is unique among developmental theories in that its postulates both: (a) that

the stages bear no invariant relationship to chronological age, and (b) that

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Associate Professor C. C. Peterson, Department

of Psychology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland 4072, Australia.

358

0001-8791/97 $25.00

Copyright q 1997 by Academic Press

All rights of reproduction in any form reserved.

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

359

CAREER STAGES

the psychological changes achieved by passing successfully through a given

stage are not necessarily permanent. Supers theory posits four stages of adult

career development: (a) exploration, (b) establishment, (c) maintenance, and

(d) disengagement. Since only the first three span the employed portion of

the life cycle, these three are the main focus of the present study.

Super (1990) argued that the timing of transitions between career stages

was more a function of the individuals personality and life circumstances

than of chronological age. For example, while one person might complete

the developmental tasks associated with his first stage of exploring career

alternatives and selecting a vocation between the traditionally normative ages

of 14 and 25 years and, by remaining in the same career throughout working

life, might later pass through each further stage just once before retiring at

age 65, this is not the only developmental possibility. The decision to extend

higher education, to dabble in widely varied career options, or to delay career

entry until the completion of childrearing may lengthen the time it takes to

pass through the exploration stage, with consequent delays in completion of

each of the subsequent stages. Similarly, adults who change careers in midlife

will pass through the stages multiple times, with subsequent passages arising

at ages well above the traditional norm. However, according to Supers theory,

unconventional timing does not automatically make the task of career development any more difficult, or carry any implication that the final outcome will

be less successful.

Supers second unconventional prediction is that the passage through a

stage need not be permanent to define optimal development. Many other stage

theories postulate that transitions are irreversible, and that only the atypical

and deleterious circumstances of illness, injury, or decline can produce regression to earlier stages (Nagel, 1957). The potential instability even of normal

and successful developmental change is implicit in Supers concept of recycling (Super, Thompson, & Lindeman, 1988). According to the recycling

notion, part of the normal developmental trajectory may include a return to

stage issues that were initially laid to rest earlier in the life cycle, and this

can facilitate personal development and coping with technological or social

change (Hall, 1992). As Super explained (1990): The concept of exploration

as something completed in mid-adolescence has been shown to be invalid

(p.237). He viewed career decision-making as a lifelong process in which

people continually strive to match their ever changing career goals to the

realities of the world of work. In addition to these personal development

needs, such social forces as economic downturns, layoffs, computerization,

and the advent of new technologies, or new career paths within the organization can all stimulate regressive recycling backward through career stages.

But, unlike the regressions of child and adolescent psychology, where problematic losses of developed capacity are seen to arise, the process of reverting

to earlier stages in Supers scheme through recycling is viewed as a means

for enhancing maturity, coping power, and creative productivity. As Hall

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

360

SMART AND PETERSON

(1992) explained: Exploration [during mid-career] can lead to trial activity,

new choices, identity changes, and increased adaptability and personal

agency (p. 247). Thus Super (1990, p. 237) proposed that so-called unstable (or multiple-trial) careers and midcareer crises were not only normal

but psychologically advantageous in a climate of rapid social change.

Despite the theorys intuitive appeal and obvious relevance to the career

counseling of mature adults (Bocknek, 1976; Sharf, 1992), there has been

surprisingly little empirical study of either of these two controversial postulates of Supers theory. Super et al. (1988) gave a brief report of an unpublished survey of a group of teachers and health professionals who were attending a one-day conference. All were at a similar stage in the process of

considering second careers, with no concrete plans to change careers. Their

chronological age and career tenure therefore predicted lesser concern with

exploration issues than with establishment or maintenance. The data largely

supported these predictions. However, as the study included no comparison

group of adults who were further advanced in the career-change process, its

results failed to answer more basic questions such as whether exploration

stage concerns are heightened during the process of midlife career change,

or whether these decline again once stability is regained. A group of workers

who were fully embarked on a second career would have been needed to test

this predictions like these.

In a more complete test of these two theoretical postulates, Perosa and

Perosa (1984) interviewed a sample of 134 men and women in the United

States who were selected for the study because they had voluntarily decided

to change careers. There were three subgroups, each at different stages of

implementing a career transition. The persisters intended to change but

had made no moves to do so, the changing group had quit their original

jobs but had not yet embarked on new ones, and the changed had already

entered their second occupations. Perosa and Perosa used the Career Development Inventory (CDI), developed by Super, Thompson, Lindeman, Jordaan,

and Myers (1981), to measure involvement in Supers stages. The CDI rates

career-stage concerns on a unidimensional continuum ranging from not yet

a concern to me (scored 1), through of great concern to me now (scored

3), to no longer a concern (scored 5).

Little support for Supers (1990) recycling postulates arose in this study.

In fact, the only significant difference among the three career-change groups

was a marginally higher tendency for the changed to be more concerned

than the changers or the persisters with the exploratory issues of Supers

first stage. While the direction of this difference is opposite to that predicted

by the recycling theory, this could be an artifact of the way the CDI was

scored. The response measure confounded timing with intensity of concern.

Thus respondents who had rated issues related to career exploration as no

longer a concern would have earned higher scores than those who rated

them of great concern to me now, yet the lowest scores of all would have

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

361

CAREER STAGES

been earned by those equally low in present concern to the first group, but

who had happened to select the not yet a concern response option to depict

timing. Thus, while one possibility was that the group who were in the throes

of career change were not experiencing heightened concern with issues related

to exploration that was predicted by Supers theory, another possibility was

the changed groups higher scores reflected a decline in concerns with

exploration now that their new careers were becoming established. A further

limitation of Perosa and Perosas study was the absence from the sample of

traditional workers of similar chronological ages with no intention of changing

career. Such a group would have provided a necessary baseline comparison

for the three actively changing groups.

Therefore, the major aim of the present study was to provide a clearer

empirical test of Supers (1990) postulate that recycling through concerns

with early developmental stages is a normal and desirable part of the process

of career change. We compared the developmental stage concerns of a sample

of employed men and women who were roughly evenly distributed among

the following four phases in the process of taking up second careers: (a)

considering the possibility of career change, but no concrete plans, (b) definitely intending to change: a new field of work has been chosen, (c) actively

implementing the move to a new career, and (d) a recent career change has

been made: this group is fully embarked on the new career. In addition, a

control group of workers of similar age, gender, education and occupational

background who had no intention of changing their original careers was

included for comparison. To avoid confounding voluntary career change with

issues like unemployment, homemakers reentry into the labor force, or elderly workers planning for retirement, the sample was limited to adults under

age 50 who were employed at the time. On the basis of Supers theory of

recycling, we predicted higher levels of concern with exploration issues

among men and women who were actively engaged in the process of making

a career change than among those who had either already completed a career

change or expressed no intention of doing so.

An issue of secondary interest was the possible relation between job satisfaction and the transition to a second career. The results of a number of recent

studies have suggested that workers who are forced to move into new careers

by reason of retrenchment, unemployment, workplace computerization, and

so on are apt to gain less satisfaction from their new jobs than from their

old ones. For example, when Shamir and Arthur (1989) studied a group of

professionals in Israel who moved to new careers after varying periods of

unemployment, they found that duration of unemployment and size of the

discrepancy between former and subsequent occupations were both negative

predictors of satisfaction with the move. Similarly, Ackerman (1990) found

that middle-aged women who desired and planned for new careers while still

in their initial field of employment lost less job satisfaction through a career

move than those who made unplanned changes after being forced out of the

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

362

SMART AND PETERSON

original occupation. While suggesting that midlife career change could be

both a cause and a consequence of diminished job satisfaction, data on involuntary career changes are complicated by the fact that such precursors to job

change as retrenchment, demotion, or unemployment may themselves diminish job satisfaction quite apart from any effect of changing jobs per se. Indeed,

the results of some anecdotal and open-ended interview studies of small

samples of career changers have suggested that it is possible to maintain very

high levels of satisfaction across the voluntary transition into a new career,

even when income and occupational prestige decline with the move (Clopton,

1973; Kelleher, 1973; Stetson, 1973; Thomas, 1980).

By means of cross-sectional comparison among groups of adults, matched

in other respects, who occupied each step in the progression from stability

in the original career through the planning, implementation, and complete

immersion in a new one, the second goal of the present study was therefore

to explore the possibility that satisfaction with work varies systematically

with progress through a career change. On the grounds that unhappiness with

the former job could both motivate change and arise as a consequence of it,

we predicted lower levels of job satisfaction during three intermediate steps

in the process than for the nonchanging group or for those whose career

changes were fully completed. In addition, on the grounds of Supers (1990)

suggestions about the normality of recycling and the argument that a career

chosen in midcareer may permit a better match to mature developmental

needs than a job chosen in adolescence (Hall, 1992), we likewise predicted

greater satisfaction among adults who had recently completed a career change

than among the stable control group. To explore these predictions regarding

satisfaction in depth, we included measures of contentment with the overall

pattern of ones career development, as well as standard indices of satisfaction

with the job itself.

In summary, the studys three main hypotheses were:

1. Adults who are in the midst of the transition into a second career will

experience greater concern with the issues bound up with Supers initial

stage of career exploration than adults of similar age, education, occupational

background, and organizational tenure who (a) have no intention of ever

changing careers, or (b) have completed a recent career transition and are

fully embarked upon the second career.

2. The same pattern of contrasts as predicted by Hypothesis 1 should apply

to concerns with Supers establishment and maintenance stages, although

possibly at an attenuated level. Until exploration issues are fully resolved in

the second career, questions of becoming established or maintaining a position

in it may assume secondary importance. However, given that a radical career

change disrupts the normal developmental patterns of working life that nonchangers may take for granted, we anticipated that adults who changed careers

would experience somewhat more concern about establishment and mainte-

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

363

CAREER STAGES

nance issues than would members of the nonchanging control group. (Given

that Supers final disengagement stage deals specifically with preparation for

retirement, we advanced no hypotheses regarding this stage. We anticipated

relatively low levels of concern with this stage because our sample was

restricted to adults under 50.)

3. Adults who are currently in the process of making a career change will

report less satisfaction with their present jobs and with their overall patterns

of career development than adults who have no intention of changing careers;

these latter, in turn, will report less satisfaction with their jobs and career

progress than adults who have recently completed a transition into a second

career and are reporting on their new occupations.

METHOD

Participants

The sample consisted of 226 Australian adults, 88 males and 138 females,

with a mean age of 29.87 years (SD 8.40). Of the total sample, 41% were

married at the time or in a de facto relationship, 39% were single, and 20%

were widowed, divorced, or separated. Their present levels of education

ranged from incomplete high schooling (1%) through technical diplomas (pretertiary: 12%) to postgraduate university degrees (56%), with 87% having

completed at least some university education. In order to be eligible to take

part in the study, individuals had to: (a) be under 50 years of age, (b) be

employed at the time, and (c) have made no more than one radical career

change (defined as change to a new type of occupation rather than to

move to a new firm, position, or rank in the same occupational field) in their

working lives.

Of the sample as a whole, the largest group (36%) were educators who

taught in kindergartens, primary schools, high schools, universities and workplace settings. The next largest group (23%) were employed in administrative/

clerical jobs (e.g., secretary, accountant, personnel manager, bank teller). The

fields of health (e.g., doctor, nurse, psychologist, counselor) supplied 11%,

while a miscellaneous collection of individual occupations provided a further

10% of the sample (e.g., soldier, minister, journalist, waitress). Next came 6%

who were in management (e.g., company directors, company managers, state

sales manager), followed by the fields of law/welfare (e.g., solicitor, corrections

officer, youth worker) and sales (e.g., sales consultant, sales assistant), each

supplying 5%. The field of science and technology (e.g., computer programmer, scientist, engineer) provided the remaining 4% of the total sample.

Measures

Career change progress. The workers current position in the progression

out of an old career into a new one, (Supers notion of recycling), was

measured using Super, Thompson, Lindeman, Myers, and Jordaans (1986)

scale. Reproduced verbatim, this measure stated:

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

364

SMART AND PETERSON

After working in a field for a while, many persons shift to another job for any of a

variety of reasons: pay, satisfaction, opportunity for growth, shut-down, etc. When the

shift is a change in field, not just working for another employer in the same field, it is

commonly called a career change. Following are five statements which represent

various stages in career change. Choose the one statement that best describes your

current status:

1. I am not considering making a career change.

2. I am considering whether to make a career change.

3. I plan to make a career change and am choosing a field to change to.

4. I have selected a new field and am trying to get started in it.

5. I have recently made a change and am settling down in the new field.

These five choices were treated categorically to form nonchanger, contemplating, choosing field, implementing, and change-completed

groups.

Career stage concerns. A respondents present level of concern with issues

typifying each of Supers four developmental stages was measured by Super et

al.s (1988) Adult Career Concerns Inventory (ACCI). This measure assesses

respondents levels of concern with Supers four stages of career development

and is an updated version of an earlier instrument known as the Career

Development Inventory: Adult Form (CDI), which was developed by Super

et al. (1981). Although the ACCI is new, the evidence of its factorial validity

is encouraging, in line with earlier findings for the CDI. At least four separate

factor-analytic studies assessing the CDI have revealed four factors corresponding closely to the four stages of Supers theory (Cron & Slocum, 1986;

Ornstein & Isabella, 1990; Phillips, 1982, Zelkowitz, 1974). In addition, Smart

and Peterson (1994a) evaluated the more recent ACCI. Results supported its

factorial validity by showing four factors congruent with Supers four-stage

model. For the present study, a short (48 item) form of the ACCI was used,

containing 12 items representing each of the four stages. Examples included:

Clarifying my ideas about the type of work I would really enjoy (exploration), Achieving stability in my occupation (establishment), Keeping in

tune with the people I work with (maintenance), and Developing more

hobbies to supplement work interests (disengagement). For each item, respondents marked a 5-point scale to indicate the strength of their present

concern with each issue. These ratings were scored from 1 no concern

to 5 great concern. Each participants ratings of the 12 items representing

a given stage were summed and averaged to yield scores for each stage that

could range from a low of 1 to a high of 5. The Cronbach alpha coefficients

for the present sample ranged from .83 to .96, thus comparing favorably with

previous research using the CDI (Ornstein & Isabella, 1990) and indicating

adequate internal consistency of the four distinct stages.

Job satisfaction. The Job Descriptive Index (JDI; Smith, Kendall, & Hulin,

1969) measures five facets of job satisfaction: (a) enjoyment of the work itself,

(b) satisfaction with supervision, (c) satisfaction with pay, (d) satisfaction with

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

365

CAREER STAGES

chances for promotion, and (e) satisfaction with co-workers. The items consist

of adjectives or adjectival phrases such as routine, challenging, gives

a sense of accomplishment, and on your feet. Response alternatives are

yes, no, or uncertain, scored 3, 0, and 1, respectively. Scores are

summed and averaged to produce a mean for each facet. The global satisfaction score (used in the present study), the mean of these five facet means,

ranges from 1 to 3. Price and Mueller (1981) reviewed the reliability and

validity of the JDI and reported that there is strong evidence for both. For

the present sample, Cronbachs alpha reliability for global job satisfaction

was .92, consistent with past alpha coefficients reported in Cook, Hepworth,

Wall, and Warr (1981) ranging as high as .93. This sound evidence of internal

consistency is also in accord with findings by Morrow and McElroy (1987).

Career satisfaction. Respondents levels of satisfaction with the overall

shape of their careers in terms of career progress and career development

were assessed using a four-item measure adapted from Romzeks (1989)

career satisfaction scale. One of the items assessing progress asked: Overall,

how satisfied are you with your career progress? and one assessing career

development asked: How satisfied are you with the amount of opportunity

available in your present job for career or professional development? Responses were recorded on 5-point scales from very dissatisfied (scored 1)

to very satisfied (scored 5). Owing to (a) the conceptual overlap between

concepts of progress and development and (b) the small number of items

used to assess each, we combined scores on the two pairs of items and divided

the total by 4 to obtain a mean career satisfaction score that could range from 1

to 5. The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the present sample was .85, indicating

adequate internal consistency.

Procedure

Self-administered questionnaires containing all measures used in the study

and an introductory letter explaining the nature and purpose of the study were

completed privately and anonymously by each participant and returned to the

researchers in a prepaid envelope. The sample, recruited from multiple

sources, was occupationally diverse. In order to obtain participants who were

likely to be considering or implementing a career change, part-time university

students who were taking evening classes while working were canvassed, and

consequently accounted for 63% of the final sample. The remainder were

volunteers who were at that time employed in schools, banks, and sales.

These adults were recruited through personal contacts and notices distributed

in their organizations inviting them to complete an anonymous questionnaire

on career planning.

RESULTS

A series of preliminary analyses were conducted to determine whether the

five career-change groups were comparable on demographic variables that

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

366

SMART AND PETERSON

might be correlated with the dependent measures. Degrees of freedom for

some analyses vary slightly owing to missing values on a few items.

A one-way ANOVA comparing the mean ages of respondents at each of

the five stages of career-change planning revealed no significant differences,

F(4, 220) 2.40, p .05. There were likewise no significant differences

among the groups in gender composition, x2 (4, N 226) .80, p .50.

Members of each of the five groups had averaged a similar number of years

in their present career positions (including the effects of promotions), F(4,

220) 1.16, p .25. They had also each spent a similar mean number of

years in the employ of their present organization, F(4, 220) 1.42, p .20.

Their levels of precareer and postcareer education were equivalent, with no

statistically significant differences emerging among the five career-change

groups either in the level of education achieved prior to career entry, F(4,

220) 2.33, p .05, or in their present levels of education (including the

results of study completed during working life), F(4, 220) 2.12, p .05.

Likewise, they averaged a similar number of hours of work per week in their

present job, F(4, 220) .65, p .60.

In terms of family life, about half the members of each career-change group

were involved in a couple relationship at the time (married or de facto), with

the remainder being single, separated, divorced, or widowed. There were no

significant differences among the groups in the proportion who were involved

at the time versus uninvolved in couple relationships, x2 (4, N 226)

3.31, p .50. However, a statistically significant difference did emerge in

the number of dependent children being cared for by members of the five

career-change groups, F(4, 220) 6.30, p .001. A post hoc Newman

Keuls test at the p .05 level revealed that the nonchanging group and the

group who had already completed a change did not differ significantly from

one another, but had fewer dependent children than members of the three

groups who were actively involved in making a career change, who likewise

did not differ significantly from one another. However, the fact that mean

numbers of dependent offspring for the former two groups averaged 2.60 and

3.39, respectively, indicated that active involvement in parenthood was the

typical condition for members of all five career-change planning groups. Thus

difference in absolute numbers of dependent offspring was not likely to limit

the possibility of testing our hypotheses through group comparison.

In sum, the five groups appeared to be highly comparable in demographic

and vocational factors apart from the planning or the implementation of a

career change itself. This enabled comparison across the groups in terms of

possible predictors and consequences of the decision to change careers.

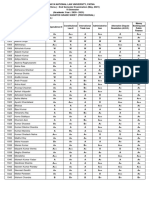

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations for the entire sample

on the dependent measures and the correlations among these variables. The

significant positive correlations among each of the four ACCI stage scores

suggest that concern with any one of Supers stages of career development

was a predictor of heightened concern with each of the others, a finding

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$1544

11-06-97 13:51:17

a

.75a

.64

.50

0.23

0.38

2.77

1.23

.80

.54

0.07

0.20

2.70

.93

2. Establishment

.62

0.13

0.18

2.45

.88

3. Maintenance

0.17

0.27

2.08

.82

4. Disengagement

Coefficients of .12 or higher are significant at p .05; and of .16 or higher, at p .01, two tailed.

Dependent variable

1. Exploration

2. Establishment

3. Maintenance

4. Disengagement

5. Global job satisfaction

6. Career satisfaction

Mean:

SD:

1. Exploration

Variable

.64

1.80

.49

5. Global job

satisfaction

TABLE 1

Intercorrelations among the Dependent Variables and Means and Standard Deviations for the Total Sample

3.32

.93

6. Career

satisfaction

CAREER STAGES

367

jvba

AP: JVB

368

SMART AND PETERSON

consistent with our second hypothesis. The four stage scores correlated negatively with the two satisfaction variables which correlated positively. These

results imply that participants who were relatively unhappy with their progress

in career development were relatively unhappy with their present jobs and

more intensely preoccupied with issues bound up with each of Supers developmental stages.

The first hypothesis predicted greater concern with exploration - stage

issues among respondents in the three intermediate stages of actively changing

careers than among those who had fully completed a change to a new career

or those in the nonchanging control group. To test this, a multivariate analysis

of variance was performed with the five career-change stages as the independent variables and ACCI scores as the dependent variables. There were no

univariate or multivariate outliers at a .001. Results of evaluations of

assumptions of normality, homogeneity of variance, linearity, and multicollinearity were likewise satisfactory.

Wilks criterion indicated the combined dependent variables were significantly affected by stage of progress through a career change, F(16, 663)

6.94, p .001, so univariate ANOVAs were performed to examine each

of Supers four career concern dimensions separately. The means, standard

deviations, and number of subjects on which these ANOVAs were based

appear in Table 2. Concern with exploration-stage issues varied significantly

as a function of career-change progress, F(4, 222) 18.76, p .001. A post

hoc NewmanKeuls test at p .05 indicated that the three groups who were

actively involved in the process of career change (contemplating, choosing,

and implementing) earned significantly higher means than the nonchangers.

In addition, the choosers and implementers means were significantly higher

than those of both the contemplating and the change-completed groups. Possibly in part as a function of the small number of participants in the latter

group (n 24), no statistically significant differences in exploration concern

emerged between respondents who had fully completed a career change and

those who were either at the initial stage of contemplating one or in the

control group with no intention of making any change. Thus Hypothesis 1

was generally support by these results.

The second hypothesis predicted heightened concern with establishment

and maintenance issues among the career changers than in the nonchanging

control group. A univariate ANOVA for concern with establishment issues

yielded a significant difference as a function of career-change progress, F(4,

222) 3.50, p .01. As shown in Table 2, the strongest level of concern

was expressed by the implementing group, and a post hoc NewmanKeuls

test at p .05 indicated that this groups mean score was significantly higher

than all the others, with no statistically significant contrasts among any of the

remaining pairs of means. For maintenance concerns, the univariate ANOVA

revealed a significant effect of career change, F(4, 222) 2.62, p .05.

None of the pairwise contrasts among means reached significance on a post

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

AID

JVB 1544

/

Exploration concern

Mean

SD

Establishment concern

Mean

SD

Maintenance concern

Mean

SD

Disengagement concern

Mean

SD

Global satisfaction

Mean

SD

Career Satisfaction

Mean

SD

Variable

630c$$1544

11-06-97 13:51:17

2.32

(.81)

2.03

(.83)

1.75

(.44)

2.28

(.84)

2.00

(.84)

1.94

(.36)

3.01

(.76)

2.63

(.93)

2.44

(.92)

3.74

(.78)

2.82

(1.20)

Contemplating

(n 46)

2.07

(1.11)

Nonchanger

(n 81)

2.65

(.64)

1.36

(.48)

2.45

(.85)

2.66

(.83)

2.85

(.86)

3.60

(.89)

Choosing a field

(n 32)

Career-Change Progress

2.92

(1.02)

1.68

(.59)

2.13

(.82)

2.65

(1.00)

3.03

(.76)

3.54

(.89)

Implementing

(n 43)

TABLE 2

Career-Stage Concerns as a Function of Progress of Changing Careers

4.04

(.64)

2.15

(.32)

2.00

(.57)

2.71

(.86)

2.88

(1.11)

2.56

(1.28)

Change completed

(n 24)

CAREER STAGES

369

jvba

AP: JVB

370

SMART AND PETERSON

hoc NewmanKeuls test at p .05. This absence of variation as a function

of career change and the relatively weak concern with maintenance issues

displayed by the present sample as a whole may both be attributable to the

relative youth of the present group of respondents. All participants in the

present study were under age 50, whereas the normative age of onset for

Supers maintenance stage in a traditional single-career life cycle is between

45 and 50 years (Super, 1957). In general, the results provided modest support

for Hypothesis 2, although the most notable finding was the relative absence

of differences due to career change in establishment and maintenance concerns, as distinct from evident contrasts in preoccupation with exploration

stage at different steps in the transition to a new career.

In order to explore the possibility of differences in enjoyment of the present

job as a function of progress through a career change, a one-way ANOVA

was conducted on the global job satisfaction scores of the five groups. The

means and standard deviations appear in Table 2. A statistically significant

difference emerged, F(4, 221) 14.85, p .001. A post hoc Newman

Keuls test at the p .05 level revealed that participants who had fully

completed a career change were significantly more satisfied with their present

jobs than each of the remaining groups. The nonchanging control group, in

turn, scored significantly higher in global job satisfaction than each of the

three groups who were still actively involved in the career change process.

Finally, the implementing and contemplating groups, while not significantly

different from one another, were each more satisfied than the group choosing

a field to move into.

Career satisfaction scores for the five career-change groups likewise appear

in Table 2. The univariate ANOVA was again statistically significant F(4,

22) 20.61, p .001. A post hoc NewmanKeuls test at the p .05 level

indicated that participants who had fully completed a career change did not

differ significantly from the nonchanging control group. Both of these groups

were significantly higher in career satisfaction than members of each of the

three groups who were still actively involved in the process of career change,

whereas these latter three groups did not differ significantly among one another. Thus Hypothesis 3 was fully supported by the results for global job

satisfaction but only partially supported for career satisfaction. As predicted,

the group of respondents who had recently completed a career change were

more satisfied with their career development progress than those still in the

throes of career change. There was no corresponding evidence that this group

had greater career satisfaction than the matched control group of workers

who had no intention of changing out of their original careers.

DISCUSSION

Supers concept of career recycling predicts that individuals who elect

to change their main field of career activity part way into occupational life

will pass through the full set of career stages for a second time, successively

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

371

CAREER STAGES

expressing renewed concern with each of the developmental tasks that, in a

single-career life cycle, arise only once and take roughly a decade to work

through. Our overall pattern of results supported this theory in a number of

ways. First, the notion of changes in patterns of concern with career stages

as a consequence of career change was supported by the finding that preoccupation with Supers initial stage of career exploration was stronger in adults

who were in the throes of making a transition to a new career than among a

matched group of workers of similar background who had no intention of

changing careers. Second, although the number of participants who had fully

completed a voluntary change to a new career in this sample was small, their

responses were consistent with Supers recycling postulate to the extent that

they expressed significantly less concern with the exploration stage (which

they had presumably already passed through for the second time) than the

implementing and choosing a field groups who were still in the throes

of the transition into a new career.

Concerns with Supers later stages of establishment and maintenance, as

predicted, varied less than exploration concern with progress through the

process of embarking upon a second career. However, the significant differences that did arise between career-change groups were generally consistent

with the hypothesis of heightened concern with the postexploration stages of

career development as a consequence of disrupting the rhythm of a traditional

career life cycle by deciding to switch to a new career.

While these results overall are closely in accord with Supers recycling

theory, a number of limitations of the present study do warrant consideration.

First, the present sample was cross-sectional. Thus, even though the results

of our preliminary analyses suggested that the four changing groups did not

differ from one another or from the nonchanging control group in age or any

other variable that seemed likely to affect concerns with Supers stages,

longitudinal data are needed to confirm that the same contrasts would also

arise over time as individuals progress through the process of implementing

a career transition. Second, the high average level of education and uniform

employment status of the present sample raises questions about the generalizability of these results to other samples of adults who switch to new careers.

We deliberately excluded unemployed adults or homemakers who were out

of the work force so we could focus on voluntary career change by working

men and women. Therefore, it is not clear that the present results would

generalize to these groups who are of strong interest in terms of their likely

practical needs for effective career counseling. Third, it would be important

to test the replicability of the present findings to adults in other cultures who

elect to change careers. In previous career development research, data from

Australian samples have tended to reveal patterns of career orientation that

are quite similar to those observed in the United States (e.g., Hesketh, Elmslie & Kaldor, 1990; Smart & Peterson, 1994b). However, the relative ease

with which employed adults can effect transitions into second careers is likely

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

372

SMART AND PETERSON

to vary not only with culture but also from occupation to occupation within

the same cultural environment. The fact that most members of the present

sample were highly educated, aware of their career options, and relatively

occupationally advantaged highlights the needs for further study of culturally

diverse and less advantaged groups.

The finding that participants who had fully completed the change into

a second career were just as satisfied with their overall process of career

development as stable single careerists is in keeping with Supers (1990)

view that recycling into a new career is a normal developmental outcome

with no adverse long-term implications for personal happiness or vocational

maturity. Although satisfaction with the present job and with career progress

were both lower among workers in the throes of career change than in the

two stable groups, it appears that these losses may be temporary. Indeed, the

fact that the established second career group scored as even more satisfied

with their present jobs than the single careerists is in line with Halls (1992)

notion that the undertaking of a new career in midlife can serve as an adaptive

response to the new needs and goals that can arise with adult psychological

development after initial career choices are made. On the other hand, the

lower satisfaction scores of the actively changing respondents than of the

two stable groups suggest that developmental transitions are by their very

nature stressful (Levinson, 1986), even when voluntarily chosen and beneficial in the long term. Applied to counseling, this result is consistent with the

view that clients who find themselves dissatisfied with their careers in midlife

should be encouraged to engage in systematic and extensive career exploration (Super, 1990). They should not be dissuaded from opting for a new

career either by the belief that midlife uncertainty and career instability are

abnormal (Bocknek, 1976), or by the stresses and temporary losses of

satisfaction that can diminish confidence during the process of contemplating

and implementing a move to a new career. Of course, such conclusions must

remain tentative in the absence of longitudinal data exploring rises and falls

in career satisfaction in the same individuals as they move into new careers.

In conjunction with the longitudinal study of stable, single careerists, such

data could likewise help to clarify whether job dissatisfaction and/or career

dissatisfaction arise primarily as an impetus to the decision to change careers

or as a consequence of the stress and uncertainty embodied in a career

transition itself. Such additional research is also strongly recommended as a

database in which to anchor recommendations for the career counseling of

mature adults who may wonder whether the four or so decades of an average

working life is too short a time span to permit effectively a midlife transition

into a radically new occupation (Sharf, 1992).

REFERENCES

Ackerman, R. J. (1990). Career developments and transitions in middle-aged women. Psychology

of Women Quarterly, 14, 513530.

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

373

CAREER STAGES

Bocknek, G. R. (1976). A developmental approach to counseling. Counseling Psychologist, 6,

3740.

Cook, J. D., Hepworth, S. J., Wall, T. D., & Warr, P. B. (1981). The experience of work. New

York: Academic Press.

Clopton, W. (1973, Spring). Personality and career change. Industrial Gerontology, 1217.

Cron, W. L., & Slocum, J. W. (1986). The influence of career stages on salespeoples job attitudes,

work perceptions, and performance. Journal of Marketing Research, 23, 119129.

Hall, D. T. (1992). Career indecision research: Conceptual and methodological problems. Journal

of Vocational Behavior, 41, 245250.

Hesketh, B., Elmslie, S., & Kaldor, W. (1990). Career compromise: Alternative account to

Gottfredsons theory. Journal of Counseling in Psychology, 37, 4956.

Kelleher, C. (1973, Spring). Second careers: A growing trend. Industrial Gerontology, 18.

Kohlberg, L. (1969). Stage and sequence: The cognitive development approach to socialization. In

D. Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Levinson, D. J. (1986). A conception of adult development. American Psychologist, 41, 313.

Mahoney, D. J. (1986). A exploration of the construct validity of a measure of adult vocational

maturity. In D. E. Super, A. S. Thompson, & R. H. Lindeman (Eds.), Adult Career Concerns

Inventory: Manual for research and exploratory use in counseling. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Morrow, F. C., & McElroy, J. C. (1987). Work commitment and job satisfaction over three career

stages. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 30, 330345.

Nagel, E. (1957). Determinism and development. In D. B. Harris (Ed.), The concept of development. Univ. of Minnesota Press

Ornstein, S., & Isabella, L. (1990). Age vs stage models of career attitudes of women: A partial

replication and extension. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 36, 119.

Perosa, S. L., & Perosa, L. M. (1984). The mid-career crisis in relation to Supers career and

Eriksons adult development theory. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 20, 5367.

Phillips, R. (1982). The relationship between the professional career development and the adult

life cycle for women and men. In D. E. Super, A. S. Thompson, & R. H. Lindeman (Eds.),

Adult Career Concerns Inventory: Manual for research and exploratory use in counseling.

Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Price, J. L., & Mueller, C. W. (1981) A casual model of turnover for nurses. Academy of Management Journal, 24, 543565.

Romzek, B. S. (1989). Personal consequences of employee commitment. Academy of Management Quarterly, 32, 649661.

Salomone, P. R. (1996). Tracing Supers theory of vocational development: A 40-year retrospective. Journal of Career Development, 22, 167184.

Shamir, B., & Arthur, M. B. (1989). An exploratory study of perceived career change and job

attitudes among job changers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 19, 701716.

Sharf, R. (1992). Applying career development theory to counseling, Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/

Cole.

Smart, R., & Peterson, C. C. (1994a). Supers stages and the four-factor structure of the adult

career concerns inventory in an Australian sample. Measurement and Evaluation in Counselling and Development, 26, 243257.

Smart, R., & Peterson, C. (1994b). Stability versus transition in womens career development:

A test of Levinsons theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45, 241260.

Smith, P. C., Kendall, L. M., & Hulin, D. C. (1969). The measurement of satisfaction in work

and retirement: A strategy for the study of attitudes. Chicago: Rand McNally

Stetson, D. (1973, Spring). Second careers. Industrial Gerontology, 912.

Super, D. E. (1953). A theory of vocational development. American Psychologist, 8, 185190.

Super, D. E. (1957). The psychology of careers. New York: Harper.

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

374

SMART AND PETERSON

Super, D. E. (1990). A life span, life-space approach to career development. In D. Brown, & L.

Brooks (Eds.), Career choice and development (2nd ed.). San Francisco: JosseyBass.

Super, D. E., Thompson, A. S., & Lindeman, R. H. (1988). Adult Career Concerns Inventory:

Manual for research and exploratory use in counseling. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Super, D. E., Thompson, A. S., Lindeman, R. H., Jordaan, J. P., & Myers, R. A. (1981). The

career development inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press

Super, D. E., Thompson, A. S., Lindeman, R. H., Myers, R. A., & Jordaan, J. P. (1986). Adult

career concerns inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Swanston, J. L. (1992). Vocational behavior, 19891991: Life-span career development and

reciprocal interaction of work and nonwork. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 41, 101161.

Thomas, L. E. (1980). Midlife career changes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 16, 173182.

Zelkowitz, R. S. (1974). The construction and validation of a measure of vocational maturity for

adults. In D. E. Super, A. S. Thompson, & R. H. Lindeman (Eds.), Adult Career Concerns

Inventory: Manual for research and exploratory use in counseling. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Received: August 28, 1995

AID

JVB 1544

630c$$$101

11-06-97 13:51:17

jvba

AP: JVB

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Reading Wonders - Practice.ELL Reproducibles.G0k TE PDFDocument305 pagesReading Wonders - Practice.ELL Reproducibles.G0k TE PDFDeanna Gutierrez100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Final Research ProposalDocument18 pagesFinal Research ProposalFarris Jones90% (10)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Managerial SkillsDocument3 pagesManagerial SkillsFarhana Mishu67% (3)

- Individuals With Disabilities Education ActDocument33 pagesIndividuals With Disabilities Education ActPiney Martin100% (1)

- Methods of TeachingDocument11 pagesMethods of TeachingnemesisNo ratings yet

- Letter A Lesson PlanDocument8 pagesLetter A Lesson PlanTwinkle Cambang50% (2)

- Legal Profession Cui Vs Cui December 4, 2019Document3 pagesLegal Profession Cui Vs Cui December 4, 2019Brenda de la GenteNo ratings yet

- Headway 5th Edition BrochureDocument6 pagesHeadway 5th Edition BrochureJyothi50% (6)

- Improving Students' Skill in Writing RecountDocument110 pagesImproving Students' Skill in Writing RecountFikri Irawan100% (1)

- 2 Nivel (1-5)Document38 pages2 Nivel (1-5)Uzca GamingNo ratings yet

- PerDev Mod1Document24 pagesPerDev Mod1TJ gatmaitanNo ratings yet

- Observer - University of Notre DameDocument32 pagesObserver - University of Notre DamedgdsgsdgNo ratings yet

- Department of Business Administration: Technical Education & Research InstituteDocument11 pagesDepartment of Business Administration: Technical Education & Research InstituteAnand KashyapNo ratings yet

- Pronunciation AssesmentDocument9 pagesPronunciation AssesmentRaphaela Alencar100% (1)

- Workshop On Prefabricated Modular BuildingsDocument2 pagesWorkshop On Prefabricated Modular BuildingsakanagesNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Animation and GamingDocument19 pagesPresentation On Animation and GamingGauravNo ratings yet

- Compulsary Science & Technology Model Set 2Document9 pagesCompulsary Science & Technology Model Set 2theswag9876100% (1)

- Holistic AssessmentDocument3 pagesHolistic AssessmentJibfrho Sagario100% (1)

- Seven Dimensions of Information LiteracyDocument2 pagesSeven Dimensions of Information LiteracySwami Gurunand100% (1)

- Notes T&DDocument19 pagesNotes T&DAmbarish PrasannaNo ratings yet

- IKKOS Swim CurriculumDocument5 pagesIKKOS Swim CurriculumnateboyleNo ratings yet

- First Lesson Plan TastingDocument3 pagesFirst Lesson Plan Tastingapi-316704749No ratings yet

- Take Your Time-Concept PaperDocument5 pagesTake Your Time-Concept Paperloi tagayaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae of Seng JumDocument4 pagesCurriculum Vitae of Seng Jumapi-310526018No ratings yet

- 7th Grade English SyllabusDocument4 pages7th Grade English SyllabusinstitutobahaihonNo ratings yet

- Case Study MobDocument1 pageCase Study MobRamamohan ReddyNo ratings yet

- 6th Semester Final Result May 2021Document39 pages6th Semester Final Result May 2021sajal sanatanNo ratings yet

- First Day of ServiceDocument7 pagesFirst Day of ServiceTony SparksNo ratings yet

- Paper JCT JournalDocument7 pagesPaper JCT JournalDrSilbert JoseNo ratings yet

- Learning Style To The Academic PerformanceDocument5 pagesLearning Style To The Academic PerformanceJohn Paul NonanNo ratings yet