Professional Documents

Culture Documents

When Private Shares Meet Public Interest

Uploaded by

kahirschOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

When Private Shares Meet Public Interest

Uploaded by

kahirschCopyright:

Available Formats

When private

shares

meet public

interest

Jannie Rossouw and

Adle Breytenbach

look at a unique

group of central

banks: the eight that

are privately owned.

The South African Reserve Bank (Sarb) celebrated its 90th anniversary on June

30, 2011, making it the oldest central bank in the southern hemisphere. This

milestone in the history of the central bank was marked in several ways, including

research on central banks with private shareholders, as the South African Reserve

Bank is one of a small group of such institutions.

The research reveals that few people are aware of this group. Literature pays no

specific attention to them, and virtually nothing has been published on this matter

in the recent past. It is also remarkable that there is no generally accepted list of

central banks with private shareholders,

Central bankers have surprisingly

or published comparisons on this topic.

The primary aim of this note is, therefore,

little knowledge of the institutional

to raise public awareness of this unique

structures of other central banks,

group of institutions and to encourage

as is evidenced by this review

research interest into this area of central

banking that has been overlooked for

many years. The dynamics of the relationships between central banks and their

shareholders are beyond the scope of this article, but warrant further research.

Historically the vast majority of central banks, or banks of (banknote) issue as

they were also referred to at the time, were institutions with private shareholders.

This changed in 1935, when the Reserve Bank of New Zealand was nationalised.

Nationalisation and government control of central banks subsequently gained

momentum and all central banks (with the exception of the State Bank of Pakistan)

established after World War II were established without private shareholders.

Central banks with private shareholding were reviewed extensively in

literature, most recently in 1974.1 At the time, 15 central banks had private

shareholders, but the central banks of Chile, Ecuador, Pakistan, Portugal, Mexico

and Venezuela were nationalised in 1975.

Jannie Rossouw is head of currency management at the Sarb and teaches at the

Economics department, University of Pretoria. Adle Breytenbach is a lecturer

at the Economics department, University of South Africa.

85

Central Banking

The last nationalisation was the National Bank of Austria in 2010. Before

nationalisation the Austrian government held 70.27% of the shares and Austrian

institutions held the balance. The bank had no private individuals as shareholders

at the time of its nationalisation.

Following this nationalisation, only the central banks of Belgium, Greece, Italy,

Japan, South Africa, Switzerland, Turkey and the US (Federal Reserve Banks) are

institutions with some form or another of private shareholders.

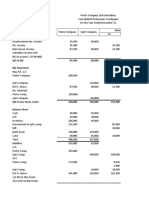

There is considerable divergence in terms of government shareholding,

persons and entities eligible for shareholding and their dividend policies. In Greece,

Italy, South Africa, Switzerland, Turkey and the US, respective governments hold

no shares in these institutions. The Belgium and Japanese governments hold, by

law, at least 50% of the shares in their respective central banks.

Of particular importance is the fact that private individuals cannot buy shares

in all these institutions. A case in point is the Federal Reserve Banks in the US,

where only member banks can buy shares. Salient features of these institutions are

summarised in the table opposite.

Differences in The table shows that these central banks have large differences in their

dividends approaches to the payment of dividends. The payment of dividends is fixed

by law in the case of Japan, South Africa, Switzerland and the US. In the case

of Italy and Turkey legislation allows for some degree of flexibility, albeit

within strict guidelines with a clear cap on the maximum dividend that can

be paid. In Belgium and Greece considerable discretion in the determination

of dividends is entrusted to the boards of these institutions. The financial

benefits of shareholding in central banks, therefore, differ considerably between

theseinstitutions.

Central bankers have surprisingly little knowledge of the institutional structures

of other central banks, as is evidenced by this review. By contrast, they have

detailed insight into the ways in which central banks conduct monetary policy, as

an extensive body of literature reviews and compares monetarypolicy conduct.

This analysis raises questions about the scope of any authority or powers of

the private shareholders of central banks. Such shareholders play no role in the

conduct of monetary policy, as monetary policy decisions cannot be subjected

to the vested interests of this small group of stakeholders in the central bank.

Central banks have to serve the best interests of all stakeholders that they serve.

The main advantage of private shareholders seems to be that they add an

another layer of governance and transparency to the conduct of central banks,

particularly in the six instances where the banks have annual shareholdermeetings.

This paper draws on Rossouw J and Breytenbach A (2011) Identifying Central

Banks with Shareholders: A Review of Available Literature, Economic History

of Developing Regions. Vol 26: Suppl 1. The views and opinions expressed in this

paper do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the Sarb or any of the

universities the authors are affiliated to.

Notes

1. See De Kock, M H (1974) Central Banking, 4th ed. London: Staples Press. Dr Mike de Kock served

as governor of the Sarb from 1945 to 1962. Central Banking, first published in 1939, was regarded as

one of the first comprehensive text books on this topic and was translated into Spanish, Portuguese,

Japanese, Hindi and Gujarati.

86

Yes

NA

Yes

Yes

No

6% of nominal value

of shares as the first

dividend. A second

dividend, calculated

as 50% of the net

proceeds after tax from

the portfolio of assets

which the bank holds as

counterpart to its total

reserves

Official government shareholding

Official shareholding by banks

Shareholding by the general public

Annual meeting of shareholders

Voting limitations

Dividend payment

Source: author research.

Yes

Trading in shares

Belgium

12% of nominal

value of shares

as a first

dividend. A

supplementary

second dividend

is annually

determined by

the General

Council (Board)

of the bank

Yes

Yes

Yes

NA

No

Yes

Greece

6% of nominal

value of shares as

a first dividend.

4% of nominal

value of shares

as a second

dividend. A third

supplementary

dividend not

exceeding 4% of

the amount of the

reserves

Yes

Yes

No

NA

No

NA

Italy

Central banks with private shareholdings: a comparison

5% of paidup capital

N/A

No

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Japan

10% of issue

value of

shares

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

Yes

South

Africa

6% of the share

capital

No

Yes

Yes

NA

No

Yes

Switzerland

6% of nominal

value of shares

as the first

dividend. A

second dividend

of a maximum

of 6% of

nominal value of

shares approved

annually by

the General

Assembly

(general

meeting) of the

bank

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

NA

Turkey

6% on stock

holding

N/A

No

No

Yes

No

No

US

When private shares meet public interest

87

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Problem: Regular Model Advanced Model Deluxe ModelDocument8 pagesProblem: Regular Model Advanced Model Deluxe ModelExpert Answers100% (1)

- Encyclopedia of American BusinessDocument863 pagesEncyclopedia of American Businessshark_freire5046No ratings yet

- Soga 37Document2 pagesSoga 37JohnsonBathNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Project Training ManualDocument15 pagesMicrosoft Project Training ManualAfif Kamal Fiska100% (1)

- Nyt1938 02 23Document1 pageNyt1938 02 23kahirschNo ratings yet

- AtlantaConstitution1920 02 23Document2 pagesAtlantaConstitution1920 02 23kahirsch100% (1)

- Giuffre Vs Maxwell Protective OrderDocument6 pagesGiuffre Vs Maxwell Protective OrderkahirschNo ratings yet

- Ghislaine Maxwell Indictment 2 July10Document18 pagesGhislaine Maxwell Indictment 2 July10kahirschNo ratings yet

- Letter of Intent To Buy: Insert Company Letter HeadDocument3 pagesLetter of Intent To Buy: Insert Company Letter HeadVelasco JerwenNo ratings yet

- 23 - GE Nine Cell MatrixDocument24 pages23 - GE Nine Cell Matrixlali62100% (1)

- Huaman Repite PlatoDocument2 pagesHuaman Repite PlatoNkma CzrNo ratings yet

- Nestle CSRDocument309 pagesNestle CSRMaha AbbasiNo ratings yet

- GEOVIA Whittle BrochureDocument4 pagesGEOVIA Whittle BrochureMahesh PandeyNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Personnel and DivisionsDocument37 pagesEvaluating Personnel and DivisionsGaluh Boga KuswaraNo ratings yet

- PGEresponseDocument37 pagesPGEresponseABC10No ratings yet

- 4b18 PDFDocument5 pages4b18 PDFAnonymous lN5DHnehwNo ratings yet

- Mott Macdonald Case StudyDocument4 pagesMott Macdonald Case StudyPanthrosNo ratings yet

- BCDR AT&T Wireless CommunicationsDocument17 pagesBCDR AT&T Wireless CommunicationsTrishNo ratings yet

- Evaluasi Kinerja Angkutan Umum Di Kota Magelang (Studi Kasus Jalur 1 Dan Jalur 8)Document10 pagesEvaluasi Kinerja Angkutan Umum Di Kota Magelang (Studi Kasus Jalur 1 Dan Jalur 8)Bahar FaizinNo ratings yet

- Royal Laundry ServicesDocument34 pagesRoyal Laundry ServicesRian Atienza EclarNo ratings yet

- Network Infrastructure PresentationDocument13 pagesNetwork Infrastructure PresentationonyinowNo ratings yet

- World Airports Freighters: FreighDocument16 pagesWorld Airports Freighters: FreighBobbie KhunthongchanNo ratings yet

- QuestionnaireDocument5 pagesQuestionnaireDivya BajajNo ratings yet

- Oil Rigs SAS Department: Contract For Works & Services at Oil Rig SitesDocument36 pagesOil Rigs SAS Department: Contract For Works & Services at Oil Rig SitesChinmaya SreekaranNo ratings yet

- The Entrepreneurial ProcessDocument13 pagesThe Entrepreneurial ProcessNgoni Mukuku100% (1)

- This Research Paper Is Written by Naveed Iqbal ChaudhryDocument5 pagesThis Research Paper Is Written by Naveed Iqbal ChaudhryAleem MalikNo ratings yet

- RAD Project PlanDocument9 pagesRAD Project PlannasoonyNo ratings yet

- Wordpress - The StoryDocument3 pagesWordpress - The Storydinucami62No ratings yet

- Latihan AdvanceDocument9 pagesLatihan AdvanceMellya KomaraNo ratings yet

- Construction Cost Handbook CNHK 2023Document63 pagesConstruction Cost Handbook CNHK 2023wlv hugoNo ratings yet

- Sky Roofing - PresentationDocument10 pagesSky Roofing - PresentationViswanathan RamasamyNo ratings yet

- Indo Gold Mines PVT LTDDocument30 pagesIndo Gold Mines PVT LTDSiddharth Sourav PadheeNo ratings yet

- Utility BillDocument1 pageUtility BillIsaiah Kipyego0% (1)

- FX4Cash CorporatesDocument4 pagesFX4Cash CorporatesAmeerHamsa0% (1)