Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Brief Note On The History of Fashion

Uploaded by

Mădălina TomaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Brief Note On The History of Fashion

Uploaded by

Mădălina TomaCopyright:

Available Formats

A Brief Note

on the History of Fashion

Richard A. Lancioni

Temple University

The introduction of the Midi in the Fall of 1970 created a general state

of confusion in the fashion industry regarding the marketability of the

new style. Retailers and manufacturers viewed the new length as an aid in

helping boost sagging sales. The dress designers felt that the Midi would

revitalize the world of fashion and that it would eventually lead to the

development of a whole new style trend for the 1970's.

But the Midi met strong resistance from the consumer. Women did not

rush out to buy the Midi as the designers and manufacturers had expected

but instead vehemently rejected the new style. Nevertheless, through an

extensive promotional campaign coupled with widespread distribution of

the Midi, the industry hoped to force the new look upon the buying public

and overcome the initial resistance to the style.

The outcome, of course, was that the Midi was not adopted by

consumers, and the marketing strategy of the fashion industry failed

miserably. The industry is still perplexed over why the Midi failed. One

explanation put forth by the fashion world is that the new style was not

treated fairly in the press. Another suggests that 1970 was not the right

time, economically, for the introduction of the completely new clothing

style. And another attributes the failure of the Midi to the general

reluctance on the part of the large dress retailers to stock the style and the

misgivings of the dress manufacturers about devoting a significant portion

of their production to it.

Each of these explanations is narrow, however, and presents only a

fragmentary analysis of the Midi debacle. The main reason why the Midi

failed was simply that the fashion industry tried to coerce the public into

buying a product it did not want. In effect, the Midi episode represented a

classical confrontation of the consumer with the industry, one in which

the industry tried to market a good that did not conform to the needs and

desires of the market place.

Could the entire Midi episode have been avoided? Perhaps it was an

128

BRIEF NOTE ON THE HISTORY OF FASHION

129

inevitable situation and destined to happen. But if various segments of the

fashion industry had been aware of certain very relevant historical

concepts previously described by fashion scholars, it is quite possible that

the introduction of the Midi would never have taken place in the manner

in which it did. In effect, knowing the historical fundamentals of fashion

retailing could have made the Midi a success rather than a failure. For

example, Paul Nystrom, as early as 1928, asserted that a fashion cannot be

forced upon the consumer through the use of commercial promotion.

Nystrom held that the consumer is a social animal composed of a group of

complex and interrelated needs that either singly or collectively interact to

change the direction of a fashion. Because of these various needs and their

interaction, Nystrom theorized, it was incorrect to assert that commercial

promotion alone could affect a change in fashion. "Commercial promotion

works successfully when it goes with a fashion trend" (p. 81), Nystrom

contended, but " . . . while styles may be created by the thousands, the

final acceptance which determines the fashion rests with the consumer,

who has in recent years shown remarkably strong tendencies to follow

certain fashion trends rather than others, and to resist all prestige sales

promotions, no matter how forcefully applied to trends in other

directions." Nystrom further stated that " I f there were any kings or

dictators of fashion in the past, there are certainly not any that are making

a success of it today, except those who are able to forecast what

consumers are going to want and then give it to them" (p. 35).

The fashion industry's tactic of using mass promotion as its primary

tool for marketing the Midi was basically incorrect. In effect, Nystrom in

1932 was quite right in asserting that there is " . . . no proof of the value of

advertising or any other form of sales promotion in stopping one fashion,

starting another, or in changing any current fashion in any marked

degree." Nystrom described the historical developments that led to the

mistaken belief that advertising or commercial promotion could control a

fashion. He stated that national advertising had come into existence only

after mass production methods had been well established and national

distribution was made possible through the development of a national

transportation system. Both of these developments were the influential

factors that determined the eventual acceptance of a new product.

Although advertising, as Nystom insisted, played only a secondary role,

manufacturers gradually began to equate the relative success of a new

product with the amount expended for advertising. This false faith in the

power of advertising, Nystrom explains was accepted by many firms in the

textile industry and resulted in their becoming extensive users of the local

and national advertising media (pp. 4-5).

130

LANCIONI

Another author, Elizabeth Hurlock, writing in 1929, reiterated

Nystrom's point that a fashion cannot be forced. She stated that "Today

there are no voluntary laws which make us accept a fashion. No fashion is

imposed upon an individual by force." The consumer, Hurlock insisted, is

free to make his own decision, and no amount of commercial promotion

or advertising can make an individual accept a fashion he does not want.

Other authors, besides Nystrom and Hurlock, while they did not

perceive a causal relationship between the needs of the consumer and the

successful introduction of a new style, did recognize that fashion was a

form of self-expression and gratification and that it therefore fulfilled

specific individual psychological needs. Their concepts were only one step

removed from the beliefs shared by Nystrom and Hurlock that a new style

must be compatible with the needs of the consumer in order to be

successful. For example, L. W. Flaccus, writing in 1906, saw that clothing

styles were a reflection of a society's goals and aspirations. Flaccus viewed

fashion as a social force and held that understanding the phenomenon of

fashion and the reasons for fashion changes provided a reliable basis for

understanding society.

Like Flaccus, W. I. Thomas (1908-9) felt that fashion was a social force

and the collective expression of an individual's feelings about life.

According to Thomas,

Man is naturally one of the most unadorned of animals,

without brillant appearance or natural glitter, with no

plumage, no spots or stripes, no naturally sweet voice, no

attractive odor, and no graceful antics, all man has is his own

character that makes him different and attractive. But thanks

to his hands he has the power of collecting brilliant objects

and attaching them to his person and when combined with his

own individual act of self-expression, he thus becomes a rival

in radiance of the animals and flowers.

Gabriel Tarde, in his work the Laws of Imitation, viewed the

phenomena of fashion as being cyclical in nature with each new style being

only an imitation of what existed in the past. The reappearance of certain

styles, he concluded, is grounded in the wants and needs of individuals in a

society. In Tarde's view, the fashion an individual selects " . . . a n d

welcomes and follows is the one that meets his pre-existant wants and

desires which are the outcome of his habits and c u s t o m s . . . "

Therefore, the power and influence the consumer has in determining the

selection of clothing styles and his influence on the eventual adoption of a

style have historically been emphasized throughout the fashion literature.

As early as 1906, writers were discussing the importance of the consumer

BRIEF NOTE ON THE HISTORY OF FASHION

131

and the degree to which he must be considered in the design and

merchandising of new clothing styles. And up through the early 1950's,

marketing scholars were heralding the development of the "marketing

concept" whereby satisfying the product needs of the consumer was the

primary goal of all business firms. In other words, the part the consumer

plays in the market place and the influence he has over the performance of

a product is not a recently recognized phenomenon. His role has been

traditionally appreciated and recognized as a powerful force to be

reckoned with.

Perhaps, if the dress designers, retailers, and manufacturers had realized

the importance of the marketing concept and had appreciated the

warnings of Nystrom, Hurlock, and the others, the Midi debacle could

have been avoided 9

REFERENCES

Flaccus, L. W. 1906. "Remarks on the Psychology of Clothes." Pedagogical Seminar,

Vol. 13, 61-83.

Hurlock, Elizabeth B. 1929. The Psychology of Dress: An Analysis of Fashion and Its

Motives. New York: Ronald Press, p. 8.

Nystrom, Paul. 1928. The Economics of Fashion. New York: Ronald Press.

9 1932. Fashion Merchandising9 New York: Ronald Press9

Tarde, Gabriel. 1903. Laws of Imitation9 Gloucester, Mass.: Henry Holt and Co., p.

246.

Thomas, W. L. 1908-9. "Psychology of Woman's Dress," American Magazine. Vol.

LXVII, 66.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Richard A. Lancioni, Assistant Professor of Marketing Temple

University, holds a B.A. in Government Administration from LaSalle

College, an M.B.A. in Finance and Marketing from Ohio State University

and a Ph.D. in Marketing from Ohio State University. In addition to this

academic background he spent approximately four years with Alcoa

Aluminum as a Marketing Analyst. From 1968-1971 Dr. Lancioni taught

at Ohio University in Economics and Marketing. He is currently an

Assistant Professor of Marketing at Temple University. He has published

articles in all of the major marketing journals including The Journal of

Purchasing, The Journal of Retailing, and The Journal of Marketing. He is

also currently involved in co-authoring a book entitled Consumer

Behavior: The Decision Approach, to be published in 1974. In the past

Professor Lancioni has also served as Consultant to a variety of business

firms. His professional affiliations include the National Council of Physical

Distribution Management, the American Marketing Association, The

International Materials Management Association, and the American

Psychological Association.

You might also like

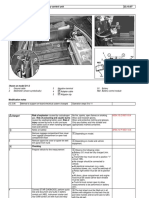

- Ford Taurus Service Manual - Disassembly and Assembly - Automatic Transaxle-Transmission - 6F35 - Automatic Transmission - PowertrainDocument62 pagesFord Taurus Service Manual - Disassembly and Assembly - Automatic Transaxle-Transmission - 6F35 - Automatic Transmission - Powertraininfocarsservice.deNo ratings yet

- Lindsay Senior Project Thesis and Project DescriptionDocument16 pagesLindsay Senior Project Thesis and Project Descriptionapi-481780857No ratings yet

- F2970.1558734-1 Trampoline CourtDocument22 pagesF2970.1558734-1 Trampoline CourtKannan LakshmananNo ratings yet

- Module - Fashion and LuxuryDocument39 pagesModule - Fashion and Luxurybobbydeb100% (1)

- An All-Consuming Century: Why Commercialism Won in Modern AmericaFrom EverandAn All-Consuming Century: Why Commercialism Won in Modern AmericaNo ratings yet

- C27 and C32 Generator With EMCP4.2 Electrical SystemDocument2 pagesC27 and C32 Generator With EMCP4.2 Electrical SystemAngel BernacheaNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Fashion Forecasting and Fashion Public Relations, 1920-1940: The History of Tobé and BernaysDocument19 pagesThe Rise of Fashion Forecasting and Fashion Public Relations, 1920-1940: The History of Tobé and BernaysoviyadsgNo ratings yet

- Intellect Fashion SupplementDocument44 pagesIntellect Fashion SupplementIntellect BooksNo ratings yet

- Create SOAP Notes Using Medical TerminologyDocument4 pagesCreate SOAP Notes Using Medical TerminologyLatora Gardner Boswell100% (3)

- Designing ClothesDocument326 pagesDesigning ClothesGunkatekaNo ratings yet

- In An Influential FashionDocument390 pagesIn An Influential FashionReham MagdyNo ratings yet

- Culture IndustryDocument22 pagesCulture IndustryKeith Knight100% (1)

- D37H-08A ManualDocument56 pagesD37H-08A Manuallijie100% (1)

- Fast - Fashion ConsequencesDocument29 pagesFast - Fashion ConsequencesMonica VeressNo ratings yet

- Technical Data Speedmaster SM 102: Printing Stock Blanket CylinderDocument1 pageTechnical Data Speedmaster SM 102: Printing Stock Blanket CylinderAHMED MALALNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Property Rights Violations in The Fashion IndustryDocument22 pagesIntellectual Property Rights Violations in The Fashion IndustryJaime ApostolNo ratings yet

- Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American DreamFrom EverandMall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American DreamNo ratings yet

- Producing FashionDocument19 pagesProducing FashionClaudia CovatariuNo ratings yet

- The Industrialists: How the National Association of Manufacturers Shaped American CapitalismFrom EverandThe Industrialists: How the National Association of Manufacturers Shaped American CapitalismRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Discrimination in The Fashion IndustryDocument25 pagesDiscrimination in The Fashion Industryapi-510849761No ratings yet

- Factors Influencing FashionDocument27 pagesFactors Influencing FashionAnanya Gilani100% (1)

- Making Makeup Respectable - Cosmetics Advertising During The GreatDocument46 pagesMaking Makeup Respectable - Cosmetics Advertising During The GreatStanislava KirilovaNo ratings yet

- The Golden Age of AdvertisingDocument8 pagesThe Golden Age of AdvertisingRobert MarcusNo ratings yet

- Politics of FashionDocument48 pagesPolitics of FashionAnca DimaNo ratings yet

- History of Marketing Thought by Bartels HermansDocument16 pagesHistory of Marketing Thought by Bartels HermansabdulqayyumaitNo ratings yet

- 75 Years of Markting HistoryDocument8 pages75 Years of Markting HistoryAadhya_LuckyNo ratings yet

- Stitched Up: The Anti-Capitalist Book of FashionFrom EverandStitched Up: The Anti-Capitalist Book of FashionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Studies of Fashion in Social ScienceDocument3 pagesStudies of Fashion in Social ScienceneelaNo ratings yet

- Fashion and AnxietyDocument24 pagesFashion and AnxietyConstantin EmilianNo ratings yet

- A02history of Marketing Thought by Bartels Hermans PDFDocument16 pagesA02history of Marketing Thought by Bartels Hermans PDFNoureddine Soltani100% (1)

- That Option No Longer Exists: Britain 1974-76From EverandThat Option No Longer Exists: Britain 1974-76Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Fashion as Cultural Translation: Signs, Images, NarrativesFrom EverandFashion as Cultural Translation: Signs, Images, NarrativesNo ratings yet

- Moeran, Brian. (2006) - More Than Just A Fashion Magazine.Document22 pagesMoeran, Brian. (2006) - More Than Just A Fashion Magazine.Carolina GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Fashion Concept: Apperception of Aesthetical ChangesDocument35 pagesFashion Concept: Apperception of Aesthetical ChangesVictor Aquino100% (1)

- Democratisation of FashionDocument12 pagesDemocratisation of FashionchehalNo ratings yet

- Why The Devil Wears Prada: The Fashion Formation Process in A Simultaneous Disclosure Game Between Designers and MediaDocument26 pagesWhy The Devil Wears Prada: The Fashion Formation Process in A Simultaneous Disclosure Game Between Designers and MediaMinda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies at Harvard UniversityNo ratings yet

- Different Perspectives on ConsumptionDocument6 pagesDifferent Perspectives on ConsumptionSaurav AnandNo ratings yet

- Fashion ProjectDocument42 pagesFashion ProjectMichael PrinceNo ratings yet

- It'S Time For A Fashion Revolution: White PaperDocument17 pagesIt'S Time For A Fashion Revolution: White PaperDana TroyoNo ratings yet

- Green Is The New Black A Dissection of Sustainable Fashion - Aditi Verma Ragini BeriDocument34 pagesGreen Is The New Black A Dissection of Sustainable Fashion - Aditi Verma Ragini Berigomesmonica75No ratings yet

- You Could Begin With The Second Sentence, and Use Some of The First at The End of The Second. (Combine The Sentences.)Document12 pagesYou Could Begin With The Second Sentence, and Use Some of The First at The End of The Second. (Combine The Sentences.)tgriff31No ratings yet

- Exploring Fashion As Communication The Search For A New Fashion History Against The GrainDocument11 pagesExploring Fashion As Communication The Search For A New Fashion History Against The GrainRNo ratings yet

- Exploring Fashion As Communication The Search For A New Fashion History Against The GrainDocument11 pagesExploring Fashion As Communication The Search For A New Fashion History Against The GrainyoursunfloshineNo ratings yet

- ConsumerismDocument5 pagesConsumerismPankaj KumarNo ratings yet

- 1.10 The Incorporation PhenomenonDocument2 pages1.10 The Incorporation PhenomenonPrincia HambNo ratings yet

- FULLTEXT02Document47 pagesFULLTEXT02dav33No ratings yet

- Digital Fashion Media: From The Book "Fashion Journalism" by Julie Bradford Chapter 3 Fashion Media and AudiencesDocument53 pagesDigital Fashion Media: From The Book "Fashion Journalism" by Julie Bradford Chapter 3 Fashion Media and AudiencesnitakuriNo ratings yet

- The Fashion: Bruno Pinheiro 8ºG Nº4Document6 pagesThe Fashion: Bruno Pinheiro 8ºG Nº4Bruno PinheiroNo ratings yet

- 02 Dress Code For Revolution - When Fashion Becomes A Political Weapon (Completed by Raj Soni and Ajitesh Kumar)Document9 pages02 Dress Code For Revolution - When Fashion Becomes A Political Weapon (Completed by Raj Soni and Ajitesh Kumar)ajiteshkumar1243No ratings yet

- DFM Sapienza - Fashion Journalism - Bradford Julie - #8Document28 pagesDFM Sapienza - Fashion Journalism - Bradford Julie - #8Sharvari ShankarNo ratings yet

- Corporate and Consumer Synergy Max and Arista FinalDocument23 pagesCorporate and Consumer Synergy Max and Arista Finalapi-252892226No ratings yet

- Consuming Advertising: The Search For Identity Through Fashion Advertising in Post-Colonial Hong Kong Anne Peirson-SmithDocument27 pagesConsuming Advertising: The Search For Identity Through Fashion Advertising in Post-Colonial Hong Kong Anne Peirson-SmithSharon HerreraNo ratings yet

- Literature Review EnglishDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Englishapi-534388013No ratings yet

- DR Jessica Bugg The Shifting Focus: Culture, Fashion & IdentityDocument8 pagesDR Jessica Bugg The Shifting Focus: Culture, Fashion & Identitycarlos santanaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Culture Focus on Spending for LifestyleDocument6 pagesConsumer Culture Focus on Spending for LifestyleGulshan ShehzadiNo ratings yet

- The Direction of Fashion Change 1Document19 pagesThe Direction of Fashion Change 1Ratul HasanNo ratings yet

- Factor of Fashion PDFDocument11 pagesFactor of Fashion PDFGashaw Fikir AdugnaNo ratings yet

- Personal Selling and Sales Management EvolutionDocument16 pagesPersonal Selling and Sales Management EvolutionEy JeyNo ratings yet

- Words That Liberate - VestojDocument11 pagesWords That Liberate - VestojsatokoNo ratings yet

- AldeDocument45 pagesAldemarketing84comNo ratings yet

- Consumerism Is A Social and Economic Order That Is Based On The Systematic Creation andDocument67 pagesConsumerism Is A Social and Economic Order That Is Based On The Systematic Creation androshandhawaleNo ratings yet

- FSH 435 - Final PaperDocument8 pagesFSH 435 - Final Paperapi-726412803No ratings yet

- Naked Marketing: A journey to the future of marketingFrom EverandNaked Marketing: A journey to the future of marketingNo ratings yet

- Interacting With Dallas - Cross-Cultural ReadingsDocument23 pagesInteracting With Dallas - Cross-Cultural ReadingsMădălina TomaNo ratings yet

- The Martian Panic Sixty Years Later - What Have We LearnedDocument4 pagesThe Martian Panic Sixty Years Later - What Have We LearnedCatrinellNo ratings yet

- Operationalizing and Analyzing Exposure - The Foundation of Media Effects Research PDFDocument16 pagesOperationalizing and Analyzing Exposure - The Foundation of Media Effects Research PDFMădălina TomaNo ratings yet

- Media Non-Transparency in RomaniaDocument24 pagesMedia Non-Transparency in RomaniaAmbra RîşcaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior, Market Segmentation and Marketing PlanDocument57 pagesConsumer Behavior, Market Segmentation and Marketing PlanShubhamNo ratings yet

- Symbolic Calculus Sage ReferenceDocument25 pagesSymbolic Calculus Sage ReferenceLn Amitav BiswasNo ratings yet

- Trends1 Aio TT2-L2Document4 pagesTrends1 Aio TT2-L2Bart Simpsons FernándezNo ratings yet

- Cronbach AlphaDocument15 pagesCronbach AlphaRendy EdistiNo ratings yet

- DP4XXX PricesDocument78 pagesDP4XXX PricesWassim KaissouniNo ratings yet

- Metaswitch Datasheet Network Transformation OverviewDocument5 pagesMetaswitch Datasheet Network Transformation OverviewblitoNo ratings yet

- TK17 V10 ReadmeDocument72 pagesTK17 V10 ReadmePaula PérezNo ratings yet

- Lali The Sun Also Rises Final PaperDocument4 pagesLali The Sun Also Rises Final PaperDaniel AdamsNo ratings yet

- HB Im70 QRDocument1 pageHB Im70 QROsamaNo ratings yet

- Advanced Java Thread Lab ExercisesDocument9 pagesAdvanced Java Thread Lab ExercisesafalonsoNo ratings yet

- 09-04-2023 - Plumbing BOQ Without RatesDocument20 pages09-04-2023 - Plumbing BOQ Without RatesK. S. Design GroupNo ratings yet

- Comparing Means of Two GroupsDocument8 pagesComparing Means of Two GroupsRobert Kier Tanquerido TomaroNo ratings yet

- 2 Science Animals Practise TestDocument2 pages2 Science Animals Practise TestThrisha WickramasingheNo ratings yet

- Che 430 Fa21 - HW#5Document2 pagesChe 430 Fa21 - HW#5Charity QuinnNo ratings yet

- Checking battery control unitDocument3 pagesChecking battery control unitjuanNo ratings yet

- Text Book Development 1Document24 pagesText Book Development 1Iqra MunirNo ratings yet

- Jyothy Fabricare Services Ltd. - Word)Document64 pagesJyothy Fabricare Services Ltd. - Word)sree02nair88100% (1)

- EC604(A) Microcontrollers and Embedded Systems Unit 2 SummaryDocument38 pagesEC604(A) Microcontrollers and Embedded Systems Unit 2 SummaryAbhay AmbuleNo ratings yet

- SYKES Home Equipment Agreement UpdatedDocument3 pagesSYKES Home Equipment Agreement UpdatedFritz PrejeanNo ratings yet

- Wag Acquisition v. Vubeology Et. Al.Document29 pagesWag Acquisition v. Vubeology Et. Al.Patent LitigationNo ratings yet

- NRBC-Internship Report - ShafayetDocument54 pagesNRBC-Internship Report - ShafayetShafayet JamilNo ratings yet

- Durgah Ajmer Sharif 1961Document19 pagesDurgah Ajmer Sharif 1961Deepanshu JharkhandeNo ratings yet

- Idioma IV Cycle Q1 Exam (2021-1) - STUDENTS ANSWERDocument9 pagesIdioma IV Cycle Q1 Exam (2021-1) - STUDENTS ANSWEREdward SlaterNo ratings yet

- TLC Treatment and Marketing ProposalDocument19 pagesTLC Treatment and Marketing Proposalbearteddy17193No ratings yet