Professional Documents

Culture Documents

IPC Project Hemant

Uploaded by

Anonymous XOcpXlCKdXCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

IPC Project Hemant

Uploaded by

Anonymous XOcpXlCKdXCopyright:

Available Formats

National Law University Odisha

Criminal Law I

Project Submission

Parasitic Liability and the accessory

Hemant Dhillon

2014/ B.B.A. LL.B. / 019

B.A. LL.B. (Hons.)

II Year, IV Semester

Submitted on : 4/4/2016

National Law University Odisha

Kathajodi Campus,

SEC - 13, CDA,

Cuttack

Criminal Law Project

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

Table of contents........................................................................................................................2

Object.........................................................................................................................................3

Research Methodology...............................................................................................................4

Research Questions....................................................................................................................5

Mode of Citation........................................................................................................................5

Introduction................................................................................................................................6

Definition of Liability............................................................................................................6

Joint criminal liability............................................................................................................6

Degrees of participation.............................................................................................................9

English Law...........................................................................................................................9

Indian Law...........................................................................................................................10

Common Intention....................................................................................................................11

Section 34.............................................................................................................................11

Guiding Principles of common intention.........................................................................13

Common intention should be Prior to the occurrence......................................................14

Intention on the spot.........................................................................................................14

In Furtherance of Common Intention...............................................................................15

Participation.....................................................................................................................16

Section 35.........................................................................................................................16

2|Page

Criminal Law Project

Common object........................................................................................................................17

Section 149...........................................................................................................................17

Essential Elements...........................................................................................................17

Difference between S.34 & S.149............................................................................................19

Bibliography.............................................................................................................................22

3|Page

Criminal Law Project

OBJECT

This project, while acknowledging the basic elements of common intention and common

object in the doctrine of Joint Criminal Enterprise brings out a contrast between the similar

looking concepts , though they being quite different from each other. It also dwells into the

different degrees of participation in a crime and how the scenario is different in Indian

criminal System as compared to the English criminal System.

The doctrine of Joint Criminal Enterprise (JCE) has provoked scholarly debate among

scholars falling into two camps. The first camp argues that the doctrine should be abandoned

as fundamentally incompatible with basic principles of individualized criminal law, while a

second camp defends the doctrine few or only minor amendments.

The purpose of this project is to analyse the prosecutorial aspects of legality and legitimacy

regarding the application of JCE as a tool in the prosecution. On one hand, the concept of

JCE is widely accepted and routinely applied before the Courts .The courts recognize and

reaffirm the lawfulness and effectiveness of the application of JCE in the prosecution against

the accused. On the other hand, the doctrine of JCE has also been highly attacked and

criticised by criminal law experts in many aspects, in particular, the expansiveness of the

doctrine raises a prospect of guilty by association, and in some circle, JCE has been referred

to as just convict everyone.

4|Page

Criminal Law Project

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The Researcher has attempted to study the nature and the evolution of Inchoate offences

along with the general theoretical stances as well as the Indian law provisions which tackles

the offences which come under the aforementioned topic.

The mode of study has involved a combination of facts, cases and explanation derived from

books, journals, online sources as well as authorities. . The sources used were secondary in

nature

The researcher has attempted to fist define the concepts involved, followed by the

explanation and the provisional aspects coupled with case authorities wherever possible.

5|Page

Criminal Law Project

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The Research Questions for the given topic are as follows

1)

What is Parasitic Liability ?

2)

What are the degrees of Participation in crime ?

3)

How are Common Intention and Common Object different from each other ?

MODE OF CITATION

The mode of Citation followed is the OSCOLA citation method.

6|Page

Criminal Law Project

INTRODUCTION

DEFINITION OF LIABILITY

Liability means legal responsibility or obligation for one's acts or omissions. Failure on part

of a person or entity to meet that responsibility leaves him/her/it open to a lawsuit for any

damages resulting out of failure or a court order to perform (as in a breach of contract or

violation of statute). In order to win a lawsuit the plaintiff must prove the legal obligation of

the defendant if the plaintiff's allegations are held to be true. This requires evidence of the

duty to act, the inability to fulfil that duty, and the connection (proximate cause) of that

failure to perform to some injury or harm caused to the plaintiff. Liability also applies to

alleged criminal acts in which the defendant may be responsible for his/her acts which

constitute a crime, thus making him/her subject to conviction and hence punishment.

JOINT CRIMINAL LIABILITY

Joint criminal enterprise or criminal liability, hereinafter referred to as JCE, is an essential

concept in international criminal law. The development of JCE has been found to be

controversial from the beginning, and numerous scholars have called for limited and careful

application of a principle that could lead to guilt by association.

Before dwelling in deep, it is important to understand the basics of JCE liability. A joint

criminal enterprise (JCE) is not an element of a crime. Rather, joint criminal enterprise is

a mode of liability whereby members are ascribed with criminal culpability for crimes that

have been committed in furtherance of a common purpose, or crimes those are a foreseeable

result of undertaking a common purpose.

7|Page

Criminal Law Project

There are three different kinds of JCE :

the basic form (JCE I), the systemic form (JCE II), and the extended form

(JCE III). All forms of JCE share a common actus reus, consisting of the following

elements:

A plurality of persons acting in concert;

The existence of a common plan, design or purpose which amounts to or involves the

commission of a crime provided for in the Statute;

And the significant contribution of the accused to the common plan, design, or

purpose.

The three forms of JCE vary according to the mens rea of the Accused. JCE I liability is

attracted when an Accused intended to participate in a JCE and intended the commission of a

crime in furtherance of JCEs common plan. The Accused can be held liable for a crime even

though he was not directly involved in its physical perpetration, as long as his contribution to

the commission of the crime was significant.

JCE II requires that the Accused had personal knowledge of a system of ill-treatment and

intended to further that system.

JCE III is a constructive form of liability. Once established that an Accused was a

member of a JCE, he can be held liable for unintended but foreseeable crimes that

were committed in furtherance of the JCEs common plan. This means that all

members of the JCE must share the same intent. JCE III extends liability for crimes

those are committed outside the common criminal plan but were committed in

furtherance of the common plan and were a natural and foreseeable consequence of

that plan. JCE III is also known as Parasitic accessory liability in English Law.

The doctrine of parasitic accessory liability can be best explained by a simple scenario

of two defendants, D1 and D2. They have a common intention to commit crime A, and

they, in fact, go on to commit crime A. D1, as an incident of committing crime A, then

commits crime B. If D2, still an active participant of crime A, had foreseen a possibility

that D1 might commit crime B, with the relevant mens rea and in a way that is not

8|Page

Criminal Law Project

fundamentally different to what was foreseen by himself, he too would be liable for

crime B.

There are several provisions in the Indian Penal Code (IPC) which determine the liability of a

person committing a crime in combination of some others. In these cases, the persons

committing it, either have common object or common intention.

In IPC, the criminal liability is determined by the way in which the person is associated with

the crime. There are several ways in which a person becomes a participant in a crime

He himself commits it.

He shares in the commission of the crime.

When he sets a third party to commit the crime.

Helps the offender, in screening him from Law.

Basically, sections 34-38 and 149 of IPC deals with situations where joint criminal liability is

formed.

9|Page

Criminal Law Project

DEGREES OF PARTICIPATION

ENGLISH LAW

English Law with reference to participants in a crime gives the following classification of

criminals according to the role played by each :

Principal in the first degree : He who actually commits the crime ( including he who

gets it accomplished through innocent agent)

Principal in the second degree : He who being present at the commission of the

crime aids and assists in its commission

Principals in the first degree are persons who perpetrate a crime directly , i.e., through their

own hands or through an innocent medium , i.e., a person , like a child below the age of

discretion or a person of unsound mind ,who , by reason of either immaturity of

understanding or of impairment of mind , is legally incompetent to commit a crime . Thus ,

the presence of the principals in the first degree at the occurrence of an offence is not

essential .

The distinction between the two categories of principals in the first and second degree is of

little practical consequence since both are liable to be awarded with equal punishment. Those

who are not present at the time of commission of deed but are associated with it either before

or after its commission are classified as :

Accessories before the fact : Those who though not present in the scene of

occurrence or where the crime is committed , counsel , procure or command another

to commit the crime .

Accessories after the fact : Those who knowing that a person has committed an

offence knowingly receive , relieve , comfort , harbour or assist him from escaping

from the clutches of law .

Accessories at the fact are generally classified as principals of the second degree , that is as

aiders and abettors of the principal offender in the commission of the offence and who may

10 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

be actually or constructively present in the scene of occurrence . They do not actually

participate in the commission of the crime . But they remain present , actually or

constructively , at the occurrence of the crime and thereby aid , assist , encourage or abet

commission of the crime .

INDIAN LAW

The Indian Criminal System takes a totally different stance on degrees of participation. IPC

makes no distinction between principals in either the first or second degree . All those who

are present at the scene and participate in the commission of a crime are liable either as the

actual offender under the specific sections of the code or under the provisions governing the

joint and constructive liability ( Section 34 and 149 IPC ) . The IPC however makes a broad

distinction between a principal and an abettor , who correspond roughly to accessories before

the fact . Such cases are dealt within the chapter of the code under the caption ' Of abetment '

from section 107 to 120 IPC. On the other hand when the role played by the individual is that

of an accessory after the fact the code provides for a substantive offence in such cases .

11 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

COMMON INTENTION

Common Intention is generally known as a prearranged plan and acting in concert pursuant to

the plan. It must be proved that the Criminal act was done in concert pursuant to the

prearranged plan. It comes into being prior to the Commission of the act in point of time, yet

the gap between the two need not be a long one ,sometimes common intention can be

developed on the spot. The fundamental factor is a pre-arranged plan and to execute the

plan for the desired results. Each of such person will be liable in an act done in furtherance of

a common intention as if the act was done by him alone. Common Intention must not be

confused with the similar intention of several person. To constitute common intention, it is

necessary that the intention of each one of them be known to the rest of them and shared by

them.

SECTION 34

Section 34 - Acts done by several persons in furtherance of common intention

When a criminal act is done by several persons in furtherance of the common intention of all,

each of such persons is liable for that act in the same manner as if it were done by him alone.

Section 34 enshrines the principle of joint liability in the doing of a criminal act, the section is

only a rule of evidence and does not create a separate substantive offence. The feature that

makes this section distinct is the element of participation in action. The liability of one person

for an offence committed by another in the course of criminal act perpetrated by several

person arises under Section 34 if such criminal act is done in furtherance of a common

intention of the persons who join to commit a crime. There is seldom any direct proof of

common intension available and, therefore, such intention can only be inferred from the

circumstances appearing from the proved facts of the case and the proved circumstances.

12 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

In order to bring home the charge of common intention, it must be established by the

prosecution by evidence, whether direct or circumstantial, that there was meeting or plan of

minds of all the accused persons to commit the offence for which they are charged with under

Section 34, be its pre-arranged or on the spur of the moment, but it must be before the

commission of the crime. The true concept of the section is that if two or more persons

intentionally do an act jointly, the position in law is just the same as if each of them has done

it individually by himself.

The section does not mention the common intentions of all nor does it say an intention

common to all. Under the provisions of Section 34 the essence of the liability is to found in

the existence of a common intention animating the accused leading to the doing of a criminal

act in furtherance of such intention. As a result of the application of principles enshrined in

Section 34, for ex, when an accused is convicted under Section 302 read with Section 34,

legally it means that the accused is liable for the act which caused death of the deceased in

the same manner as if it was done by him alone. The provision is intended to meet a case in

which it may be difficult to distinguish between acts of individual members of a party who

act in furtherance of the common intention of all or to prove exactly what part was taken by

each of them.

A Supreme Court Bench of Justice M.B. Shah and Justice Doraiswamy Raju in the case of

Gopinath Jhallar Vs State of UP1 has stated that "even the doing of separate, similar or diverse acts by several persons, so long as they

are done in furtherance of a common intention, render each of such persons liable for

the result of them all, as if he had done them by himself.....,"

Common intention implies a pre arranged plan, which denotes prior meeting up of minds.

Common intent comes into light before the commission of the crime. Merely two accused

being at the same spot does not account to the common intention, but it is necessary to prove

the meeting up of minds prior to the actual commission of crime.

1 Gopi Nath Jhallar v State of UP [2001] 6 SCC 620

13 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

14 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

GUIDING PRINCIPLES OF COMMON INTENTION

In Mahboob Shah v. Emperor2, the following principles were laid down by the court :

Under section 34 of IPC, essence of liability is to be found in the existence of a

common intention, animating the accused, leading to doing of a criminal act in

furtherance of such intention.

To invoke the aid of section 34 successfully, it must be shown that the criminal act

complained against was done by one of the accused persons in furtherance of the

common intention; if it is so then liability for the crime may be imposed on any one of

the persons in the same manner as if the acts were done by him alone.

Common intention within the meaning of section 34 implies a prearranged plan, and

to convict the accused of an offence applying the section it should be proved that the

criminal acts were done pursuant to the prearranged plan.

It is difficult, if not impossible to procure direct evidence to prove the intention of an

individual, in most cases it has to be inferred from his act or conduct or other relevant

circumstances of the case

Care must be taken not to confuse same or similar intention with common intention;

the partition which divides their bounds is often very thin; nevertheless, the

distinction is real and substantial and if overlooked will result in miscarriage of

justice.

The inference of common intention within the meaning of the term under section 34

should never be reached unless it is a necessary inference deductable from the

circumstances of the case.

2 Mahboob Shah v Emperor [1945] AIR 118 (PC)

15 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

COMMON INTENTION SHOULD BE PRIOR TO THE OCCURRENCE

In Pandurang v. State of Hyderabad3, the Supreme Court observed that it is well

established fact that a common intention presupposes prior concert. It requires pre-arranged

plan because before a person can be vicariously held liable for the criminal act of another, the

act must have been done in furtherance of the common intention of them all. The inference of

common intention should never be reached unless it is a necessary inference deducible from

the circumstance of the case. The incriminating facts must be incompatible with the

innocence of the accused and incapable of explanation on any other reasonable hypothesis.

INTENTION ON THE SPOT

In certain cases, an intention can be formed on the spot. It is not always necessary that all the

accused have meditated the crime, well in advance. In certain cases, the intention can be

formed on the spot. In a fight, all the accused may at a point decide to take out their revolvers

and shoot the people of the other party, in order to kill them. Here the decision of killing the

people of the other party was taken on the spot.

The issue of liability of different members of a group of people divided into mutually

antagonistic or hostile groups, especially when there is a free fight between them, is one of

the most difficult aspects of joint liability.

In Balbir Singh v. State of Punjab4 a similar question was raised, wherein four persons each

belonging to two different groups attacked each other and in the result, one person died. Both,

the trial court and the High Court had held that there was a free fight and every assailant was

accountable for his own acts committed. However, the Supreme Court held that, in a free

3 Pandurang v State of Hyderabad [1955] AIR 216 (SC)

4 Balbir Singh v State of Punjab [1955] AIR 1956 (SC)

16 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

fight, there was a movement of body of the victims and assailants and in such a situation it

will be difficult to specifically ascribe to one accused the intention to cause injuries sufficient

to cause death.

IN FURTHERANCE OF COMMON INTENTION

The principle of joint liability arises out of common intention followed by an act in

furtherance of such common intention. This has been clearly stated in the case of Mahboob

Shah v. Emperor wherein one Allah Dad was shot dead by a bullet from the gun used by one

of the accused who came to rescue their cousin, who had been attacked by Allah Dad and

shouted for help. The two accused were armed with a guns, and each one of them aimed at

two different individuals shot from the gun of Wali Shah, the latter only received injuries

from a bullet shot by Mahboob Shah. Of the three accused, Wali Shah, whose shot killed

Allah Dad, absconded and could not be brought on trial. The other two were tried and

prosecuted under section 302 read with section 34 IPC. The sessions judge convicted him and

awarded death penalty.

On appeal to the Lahore HC, the Lordships held that the case fell well within the ambit of

section 34 and as to their common intention, it was said that common intention to commit

the crime which was eventually committed by Mahboob Shah and Wali Shah came into being

when Ghulam Qasim Shah shouted to his companions to come to his rescue, and both of

them emerged from behind the bushes and fired from their respective guns. Their Lordships

of the Privy Council however disagreed with the view of the judges of the Lahore HC.

In their opinion there was no evidence of the common intention to the evidence that the

appellant just have been acting in concert with Wali Shah pursuance of a concerted plan

when he along with him rushed to the help of Ghulam Qasim. In their view the common

intention of both was to rescue Ghulam Qasim and both of them picked up different

individuals to deal with. Evidence is lacking to show that there was any pre-mediation to

bring about the murder of Allah Dad. At the most they can be stated to have a similar

intention, but not a common intention and one should not be confused with each other.

Hence, the Privy Council set aside the conviction and sentence of murder as imposed by the

High Court.

17 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

18 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

PARTICIPATION

Participation is a necessary element or condition precedent to finding of joint liability. The

Supreme Court in the case of Kantiah Ramayya Munipally v. State of Bombay5 observed

that, it is the essence of section 34 that the person must be physically present at the actual

commission of crime. He need not be present on the actual spot, he can, for instance, can

stand outside to warn his companions about any approach of danger.

SECTION 35

Section 35 of the IPC is in furtherance of the preceding section 34. It reads that

Sec 35 - When such an act is criminal by reason of its being done with a criminal

knowledge or intention.

Whenever an act, which is criminal only by reason of its being done with a criminal

knowledge or intention, is done by several persons, each of such persons who joins in the act

with such knowledge or intention is liable for the act in the same manner as if the act were

done by him alone with that knowledge or intention. If several persons, having the same

criminal intention or knowledge jointly murder, each one would be liable for the offence as if

he had done the act alone; but if several persons join in the act, each with different intention

or knowledge from the others, each is liable according to his own intention or knowledge.

Reference can be made to the case of Adam Ali Taluqdar6 where A and B beat C who died.

A had an intention to murder C, and knew that his act would cause his death. B on the other

5 Shreekantiah Ramayya Munipalli v The State Of Bombay [1955 ] AIR 287

6 Adam Ali Taluqdar v King Emperor [1927] AIR 324 (Cal)

19 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

hand intended to cause grievous hurt and did not knew that his act will cause Cs death.

Hence, A was held guilty for murder whereas B was charged with grievous hurt.

20 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

COMMON OBJECT

Common object: the word Object means purpose or design to make it common, it must be

shared by all. It might be formed at any stage by all or few members. It may be modified ,

altered or abandoned at any state. Common object may be formed by express agreement after

mutual consultation. The sharing of common object would, however, not necessarily require

the member present and sharing the object to engage himself in doing an over act. Therefore

this section is inapplicable in a case of sudden mutual fight between two parties, because of

lack of common object.

SECTION 149

Section 149 - Every member of unlawful assembly guilty of offence committed in

prosecution of common object

If an offence is committed by any member of an unlawful assembly in prosecution of the

common object of that assembly, or such as the members or that assembly knew to be likely

to be committed in prosecution of that object, every person who, at the time of the

committing of that offence, is a member of the same assembly, is guilty of that offence.

ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS

To invoke section 149 IPC, the following ingredients must be present

There must be an unlawful assembly. There must be at least five people in such an

assembly.

There must be some common object of such an unlawful assembly. Here the word

common must be distinguished from similar; it means common to all and known

21 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

to the rest of them and also shared by them.

There must be a commission of offence by anyone or more members of such unlawful

assembly.

The commission of such offence must be in prosecution of the common object shared

by all and each of the members of such unlawful assembly.

The offence committed in prosecution of a common object must be such that each one

of the members of such unlawful assembly knew was likely to be committed.

In Mizaji v. State of Uttar Pradesh7 it was stated that S149 IPC has two parts. The liability

of a member of an unlawful assembly may arise for an offence committed by any member of

the assembly in two ways. The first is where the other members commit an offence, which

was in fact the common object of the assembly. The second is where the common object to

commit an offence was different from the offence, which was actually committed.

For example, the accused X, Y, Z, J and K were alleged to have entered into As house in

order forcible possession of the house. With the lathis they were carrying, grave injuries were

inflicted on As limb and he was dragged out of the house to some distance where either J or

K shot him with a hidden pistol.

In such a case, the member who did not actually commit the offence will be liable for that

offence only if he knew that such offence was likely to be committed in the course of

prosecution of the common object to commit the offence originally thought of. The

expression know does not mean a mere possibility, such as might or might not happen, it

imports a higher degree of probability. Further, it indicates a state of mind at the time of

commission of the offence and not the knowledge acquired in the light of subsequent events.

Under section 149, the liability of the other members for the offence committed during the

occurrence rests upon the fact whether the other members knew beforehand that the offence

actually committed was likely to be committed in prosecution of the common object. Such

knowledge may be reasonably collected from the nature of the assembly, arms or behaviour

at or before the scene of action8.

7 Mizaji v. State of Uttar Pradesh v State of Uttar Pradesh [1959] AIR 572 (SC)

8 Gajanand v State of Uttar Pradesh [1954] AIR 695 (SC)

22 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

23 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN S.34 & S.149

There is a close resemblance between common intention and common object, though both of

them belong to different categories of the office in criminal law i.e., ( S 34 and S 149 )

respectively .The principal element in S 34 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) is the common

intention to commit a crime. In furtherance of the common intention several acts may be done

by several persons resulting in the commission of that crime. In such a situation s. 34

provides that each one of them would be liable for that crime in the same manner as if all the

acts resulting in that crime had been done by him alone. There is no question of common

intention in s.149 of the Indian Penal Code.

An offence may be committed by a member of an unlawful assembly and the other members

will be liable for that offence although there was no common intention between that person

and the other members of the unlawful assembly to commit that offence provided the

conditions laid down in the section are fulfilled.

Thus, if the offence committed by that person is in prosecution of the common object of the

unlawful assembly or such as the members of that assembly knew to be likely to be

committed in prosecution of the common object, every member of the unlawful assembly

would be guilty of that offence, although there may have been no common intention and no

participation by the other members in the actual commission of that offence.

There is a difference between common object and intention.

Although, the object may be common, the intentions of the several members of the

unlawful assembly may differ and indeed may be similar only in one respect namely

that they are all unlawful, while the element of participation in action, which is the

leading feature of s. 34, is replaced in s. 149 by membership of the assembly at the

time of the committing of the offence.

'Common intention ' in Section 34 is undefined and therefore unlimited in its

operation , while 'common object ' in Section 149 cannot go beyond the five objects

specifically indicated in Section 141 of the IPC

The crucial difference between common intention and common object is that while

24 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

common intention requires prior meeting of mind and unity of intention , common

object may be formed without these ingredients.

Difference Between S 34 & S149

Base

N a t u r e o f O ff e n s e

Section34

This section is not a

Section 149

This section is a substantive

substantive office it is only a

offense, it also read with

role of evidence. it always

other sections. Punishment

read with other substantive

can be imposed solely upon

offices. Punishment cannot

this section .Where as

be imposed solely upon this

prosecution file a charge

section. For example if a

sheet u/s

person convicted u/s 302 r/w

34 of IPC can legally be

convicted u/s 302 r/w 34.

Common intention- the

Common Object: the

principle ingredient of this

principle element of this

section is Common intention,

section is Common Object,

any act which committed in

any act which committed in

furtherance of common

prosecution of common

intention attract this section

Common intention within the

object will attract this section

Common object is defined

Range of

meaning of section 34, is

and is limited to the five

Principle

undefined and unlimited.

unlawful objects stated in

Principle element

element

Ty p e o f O ff e n s e

Necessity

section 141 of IPC.

Common Intention requires

Common object require

under this section may be of

under this section must be

ANY TYPE.

one of the object mentioned

Prior meeting of mind is

u/s 141 of IPC.

Prior meeting of mind is not

necessary before wrongful

necessary under this section.

act is done under this section.

Mere membership of an

unlawful assembly at the

25 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

time of committing the

Liability

Number of Person

Pa r t i c i p a t i o n i n

Crime

It is a joint liability. A joint

offense is sufficient.

It is a constructive liability

liability of a person is

and vicarious liability. all the

determined according to the

members of that assembly

manner in which he becomes

will be vicariously liable for

associated with commission

that offence even one or

of the crime.

more, but not all committed

Minimum two people require

the said office.

Minimum five people require

attracting this section.

Active participation in

attracting this section.

Merely membership of the

commission of crime is

unlawful assembly at the

necessary.

time of commissioning of

crime would be sufficient for

this section application,

active participation is not

necessary.

26 | P a g e

Criminal Law Project

BIBLIOGRAPHY

PSA Pillai , Criminal Law , 12th Edition , Lexis Nexis

Gaur KD, A Textbook on Indian Penal Code, 2013, Fourth Edition, Universal Law

Publishing Co.

Mishra SN, Indian Penal Code, 2008, 16th Edition, Central Law Publications

Gaur KD, Criminal Law : Cases and Materials, 2013, 6th Edition, Lexis Nexis

Butterworths Wadhwa

Bishops Commentaries on Criminal Law, Volume 1

D. Robinson, The Identity Crisis of Criminal Law, 21 Leiden Journal of Criminal

Law (2008) p. 939

JILS blogs on Indian criminal justice system

SCC blogs on Indian Criminal System

27 | P a g e

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Ibong AdarnaDocument46 pagesIbong AdarnaMarilou LumanogNo ratings yet

- Corporate Criminal Liability EvolutionDocument16 pagesCorporate Criminal Liability EvolutionAstitva SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- People V Amaca 277 SCRA 215 DigestDocument2 pagesPeople V Amaca 277 SCRA 215 DigestPrudencio Ruiz Agacita100% (1)

- Rights of Children: A Global Study AnalysisDocument24 pagesRights of Children: A Global Study AnalysisTanu PatelNo ratings yet

- Important Sections of Civil Procedure CodeDocument16 pagesImportant Sections of Civil Procedure CodeShajana Shahul89% (9)

- Laken Riley Case - Georgia Authorities Identify Murder Suspect in CustodyDocument1 pageLaken Riley Case - Georgia Authorities Identify Murder Suspect in Custodyed2870winNo ratings yet

- Isip Vs PeopleDocument1 pageIsip Vs PeopleErwin SabornidoNo ratings yet

- Checkpoint A2+ B1 Unit 2 Test BDocument5 pagesCheckpoint A2+ B1 Unit 2 Test BPaula Grzechowiak100% (1)

- WW2 ExamDocument13 pagesWW2 ExamRe Charles TupasNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Case Digest on Prescription of OffensesDocument1 pageCriminal Procedure Case Digest on Prescription of OffensesLykah HonraNo ratings yet

- DOCUMENT: Order and Directives - Restrictions On The Operations of Federal Special Anti-Robbery SquadDocument5 pagesDOCUMENT: Order and Directives - Restrictions On The Operations of Federal Special Anti-Robbery SquadSahara ReportersNo ratings yet

- Released in Part BL, 1.4 (B), 1.4 (D), B5 UnclassifiedDocument9 pagesReleased in Part BL, 1.4 (B), 1.4 (D), B5 UnclassifiedMike LaSusaNo ratings yet

- Manhunt For Husband of NYC Daycare Owner Where Tot Died Expands To DRDocument7 pagesManhunt For Husband of NYC Daycare Owner Where Tot Died Expands To DRRamonita GarciaNo ratings yet

- Naacp ProofDocument2 pagesNaacp ProofTiffany L DenenNo ratings yet

- Crimes of Moral TurpitudeDocument28 pagesCrimes of Moral Turpitudealincirja07No ratings yet

- Inter Country Adoption and Human RightsDocument30 pagesInter Country Adoption and Human RightsAnkit YadavNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Civil Law and Criminal LawDocument3 pagesDifference Between Civil Law and Criminal LawBiki DasNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of Human Rights Vol 3Document354 pagesEncyclopedia of Human Rights Vol 3mancoNo ratings yet

- Steph Jarram Storyboard - Opening of Hot FuzzDocument3 pagesSteph Jarram Storyboard - Opening of Hot Fuzzshopoholic99No ratings yet

- CORRECTIONAL ADMINISTRATION EXAM REVIEWDocument61 pagesCORRECTIONAL ADMINISTRATION EXAM REVIEWIan CañaresNo ratings yet

- The Serial Killer Whisperer by Pete Earley-Read An Excerpt!Document32 pagesThe Serial Killer Whisperer by Pete Earley-Read An Excerpt!Simon and SchusterNo ratings yet

- Amici Review Center 1000 Stars February Board ExamDocument75 pagesAmici Review Center 1000 Stars February Board ExamLorelyn Lompot100% (2)

- Chapter Iii of CRPC Deals With Power of Courts. One of Such Power Is ToDocument30 pagesChapter Iii of CRPC Deals With Power of Courts. One of Such Power Is Tocrack judiciaryNo ratings yet

- People vs Carlos Soler Indeterminate Sentence Law BenefitsDocument1 pagePeople vs Carlos Soler Indeterminate Sentence Law BenefitsJaen TajanlangitNo ratings yet

- Service of Rembrance 2011 FlyerDocument1 pageService of Rembrance 2011 FlyerrachelresnickNo ratings yet

- Georgia House Bill 426Document3 pagesGeorgia House Bill 426Alex JonesNo ratings yet

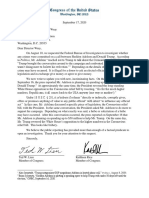

- 2020-09-17 Lieu Rice Letter To FBI On Sheldon AdelsonDocument1 page2020-09-17 Lieu Rice Letter To FBI On Sheldon AdelsonJon RalstonNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Security Guard A Security Guard (Also Known As ADocument10 pagesMeaning of Security Guard A Security Guard (Also Known As AMahak SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Module 4 Human RightsDocument15 pagesModule 4 Human RightsRHOWELLE TIBAYNo ratings yet

- Pyramid of HateDocument1 pagePyramid of HateDimitris GoulisNo ratings yet