Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Nature of Violence in The Middle Ages An Alternative Perspective

Uploaded by

Didem OnalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Nature of Violence in The Middle Ages An Alternative Perspective

Uploaded by

Didem OnalCopyright:

Available Formats

d:/70-3/47-1.

3d 1/9/97 16:3 vk/amj

HISTORICAL RESEARCH

Vol. LXX No. 173

October 1997

The Nature of Violence in the Middle Ages:

an Alternative Perspective

Abstract

An alternative perspective on the nature of violence in the middle ages is

provided by the register of the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Cerisy-la-Fore t in

Normandy. Of particular interest are the detailed descriptions of assaults and

brawls. Although numerous, these were mainly petty and unpremeditated and,

as such, they serve to highlight the exceptional and often accidental nature of

homicide, and the absence of ingrained habits of violence in the form of the

feud. This contrasts with those studies which have taken such extreme forms of

violence to be the norms and which, as a result, may have overlooked the

mundane, everyday reality of violence.

T h e s t u d y o f violence in medieval Europe is by now a well-established

field of inquiry. Those historians involved in the study of violence in its

various forms have naturally attempted to go beyond specific questions

concerning status, gender and motive, to address the wider issue of the nature

and place of violence within medieval society. In this much attention has

been paid to the findings of studies of homicide based upon the records of

the English royal courts. Here dissatisfaction with the use of letters and

chronicleswith their bias towards the unusual and the sensationaltogether

with the terse nature of the records themselves has encouraged historians to

make extensive use of statistical analysis. In his study of homicide in the

thirteenth-century eyre rolls, Professor J. B. Given applied modern criminological methods and theory to the evidence, and consequently one of his

most important tasks was to establish a homicide rate expressed as n per

100,000 of population.1 The figures which emerged from this exercise led

Given to conclude that homicide was a frequent event in medieval England,

and that most individuals would have had some experience of it, if only as

spectators, during their lifetimes. This made homicide `one of the major

social phenomena of the age'.2 In seeking an explanation for this ubiquity,

Given argued that it was ultimately a reflection of changes within thirteenthcentury English society. In a society in flux, and in which old-established

methods of social control within family and community were breaking

1

2

J. B. Given, Society and Homicide in 13th-Century England (Stanford, Calif., 1977), pp. 3540.

Ibid., p. 40.

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

Historical Research, vol. 70, no. 173 (October 1997)

Published by Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden MA 02148, USA.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

250

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ge s

down, violence had become a mechanism for conflict resolution.3 Professor

B. A. Hanawalt has also sought to go beyond the raw data gleaned from her

study of early fourteenth-century gaol delivery and coroners' rolls, although

she largely eschewed attempts to set a homicide rate.4 Violencewhich often

led to homicideagain emerges as a normal part of everyday life, and an

accepted means for the resolution of disputes and the furtherance of

individual and family interests. Homicide was one manifestation of intracommunal tensions, and was born out of the general cheapening of life in

demographic terms, and the inability of the legal system to deal quickly and

effectively with disputes.5 In reaching these conclusions, both Given and

Hanawalt take homicide to be representative of contemporary levels of

violence, and view its understanding as a key which can be used to unlock

the door to a greater understanding of the fundamental characteristics of

medieval English society.

Questions concerning the reliability of the conclusions derived from

statistical analysis have recently begun to be raised, while the debate about

the significance of homicide itself has moved on.6 Dr. C. I. Hammer, while

setting a high and possibly inaccurate homicide rate for fourteenth-century

Oxford, nevertheless produces a more qualified picture of the impact of

violence within the city by suggesting that exposure to the risk of homicide

may have varied according to age, sex, social status and geographic location.7

Dr. P. C. Maddern has gone further in her study of violence in fifteenthcentury England by broadening the debate to include officially sanctioned

forms of violence and contemporary attitudes towards the use of violence

and to question the reality of the picture derived from the evidence. She

suggests that much of the `violence' revealed in the statistics was either a legal

fiction or low-key; she makes it clear too that the use of violence was seen as

an acceptable and necessary part of the functioning of society, whether

through the use of capital and corporal punishments or the chivalrous

pursuit of warfare.8 The question addressed is not so much whether medieval

society was intrinsically more violent than later periods, but whether the

attitudes to its use, and the range of sanctioned applications, were different.

The studies outlined above have limited themselves to a consideration of

the role of violence within an English context, but a much wider canvas has

been drawn by others. Professors John Bossy and Robert Muchembled wish,

for different reasons, to construct models which capture the quintessential

nature of medieval society in the Catholic west. On the one hand, John Bossy

Given, pp. 20012.

B. A. Hanawalt, Crime and Conflict in English Communities, 130048 (Cambridge, Mass., 1979).

5

Ibid., pp. 1737.

6

See P. C. Maddern, Violence and Social Order: East Anglia, 142242 (Oxford, 1992), pp. 20f, and E.

Powell, `Social research and the use of medieval criminal records', Michigan Law Rev., lxxix (19801),

96778.

7

C. I. Hammer, `Patterns of homicide in a medieval university town: 14th-century Oxford', Past

and Present, lxxviii (1978), 11f, 22f.

8

Maddern, pp. 17f, 22f.

3

4

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ges

251

has been keen to define the particular role which the medieval church played

in the shaping of that society and to establish the changes which occurred in

the interaction between the two as a result of the Counter Reformation. On

the other, Robert Muchembled has sought to identify the changes wrought

on society by the development of a centralist state in France from the

sixteenth century onwards. Although ultimately pursuing different aims,

both nevertheless give a central place to the role of violence in the ordering

and defining of medieval society.

In a series of articles, and most recently in a general essay on the

contrasting natures of pre- and post-Reformation Catholicism, John Bossy

has presented a particular view of the role `traditional' Christianity played in

the ordering and functioning of medieval society.9 His views are grounded on

the premise that medieval society was in all its essentials a house divided

against itself. Ties of kin often proved stronger than those of community and

the practice of social amity had its counterpart in the form of institutionalized and socially divisive violence: the feud.10 In consequence, the wider

whole was in constant danger of being split asunder by the periodic eruptions

of the interests, jealousies and demands arising from kin-based loyalties. Into

this volatile and highly reactive mixture the Catholic church came as arbiter

and peacemaker, promoting a truly catholic unity. It sought to draw the sting

of institutionalized violence through the sacraments which possessed social as

well as sacred significance.11 The socially cohesive forces of amity and charity

were to be promoted through exogamy and the agency of the parish mass

which served to transcend the narrow self-interests of family.

Robert Muchembled too is a writer concerned with violence. Working

from a range of secondary sources which include Huizinga's study of later

medieval culture and society, Muchembled produces a psychological

explanation for the prevalence of violence within the medieval period.

Like Bossy, he stresses the centrality of the feud in any understanding of

violent behaviour, and this is used to support his view that the early modern

period marked a critical stage in the control and eventual suppression of

popular culture. Violence in the fifteenth century was, according to

Muchembled, characteristically unpremeditated and born ultimately from

emotional instability. Men were victims of extreme emotions and the

isolation and misery of their lives led to a fear of the `other' and consequently

to feuds between villages and even families.12 Underpinning this was the

9

J. Bossy, Christianity in the West, 14001700 (Oxford, 1985); idem, `The Counter-Reformation and

the people of Catholic Europe', Past and Present, xlvii (1970), 5170; idem, `Blood and baptism: kinship,

community and Christianity in western Europe from the 14th to the 17th centuries' in Sanctity and

Secularity: the Church and the World, ed. D. Baker (Studies in Church History, x, 1973), pp. 12943;

idem, `The social history of confession in the age of the Reformation', Trans. Royal Hist. Soc., 5th ser.,

xxv (1975), 2138.

10

Bossy, Christianity, p. 29f; idem, `Blood and baptism', p. 143f.

11

Idem, Christianity, pp. 6671; `Blood and baptism', pp. 13942.

12

R. Muchembled, Popular Culture and Elite Culture in France, 14001700, trans. L. Cochrane (Baton

Rouge, La., & London, 1985), pp. 302, 40, 45f.

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

252

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ges

anxiety born of the individual's own mortality: death walked abroad stalking

the weak. An individual could gain transitory and illusory relief from this

dreadful self-knowledge by projecting the mantle of death on to his victim:

aggression was the offspring of fear.13 With the growth of the absolutist state

in France, these aggressions were either channelled on to new scapegoats such

as witches, or were marginalized as society became better regulated and

policed.14

Various debates have therefore grown up in historical circles which focus

on the question of the nature and significance of violence in medieval society.

Most take as a basic premise that medieval society was one characterized by

violence. This premise then requires an explanation or is used as the basis for

more wide-ranging theories concerning the nature of medieval society itself.

The focus has tended to fall on England, and on certain forms of violence:

homicide and the practice of feud. However, the emphasis upon these

particular manifestations of violence begs certain questions. How representative was homicide of the everyday experience of violence? Was medieval

society, in every instance and every place, one in which a fragile peace was

threatened by the barely contained blood-lust of the feud? Indeed, on a

general level it can be argued that the preoccupation with felonies`real'

crimesand particularly violent felonies, has produced a distorted picture of

the nature of crime in the medieval and other periods. Such a narrow focus

cannot take into account the banal and mundane offences encountered

within the records of local jurisdictions, or the non-violent nature of the

majority of offences within the records of the English royal courts. Similarly

homicide rates may heighten the impression of a fundamentally violent and

disordered society, if they are isolated from the `background count' of minor

assaults, brawls, legally sanctioned violence and defamations.

The interest in this article lies with violence other than homicide, and in

particular the patterns which emerge from the quantitative and qualitative

analysis of assault cases. For England, methodological considerations have

discouraged the study of this form of violence, at least in attempts to gauge

the levels of violence pertaining in medieval society. In both the medieval

and early modern periods the researcher is faced with not only the

incomplete nature of the records, which usually make it impossible to

follow an action through to its conclusion, but also the variety of meanings

which the term `assault' could hold in Common Law. These ranged from the

simple threat of violence at one extreme to rape and attempted murder at the

other. Furthermore those studies which have utilized data relating to assaults

from the records of local jurisdictions have done so with a different set of

questions in mind.15 Assaults and other forms of non-lethal violence,

Muchembled, pp. 32f.

Ibid, pp. 18795.

15

J. G. Bellamy, Crime and Public Order in England in the Later Middle Ages (1973), p. 37; Maddern,

pp. 22f.; J. A. Sharpe, Crime in 17th-century England: a county study (Cambridge, 1983), pp. 117f; A.

Soman, `Deviance and criminal justice in Western Europe, 13001800: an essay in structure', Criminal

Justice History: an International Annual, i (1980), 6.

13

14

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ge s

253

however, may prove to be more accurate indicators of both the quality of

violence within medieval society and the extent to which it could shape

individual lives. These matters can be explored most fully through continental evidence which tends to be fuller and more detailed, and one

particularly richand unexpectedsource is the register of the ecclesiastical

jurisdiction of the officiality of Cerisy-la-Fore t in the diocese of Bayeux.16

The officiality of Cerisy was the exempt jurisdiction of the Benedictine

abbey of Saint-Vigor. The register's chronological span is broad, with the

first item of business recorded in 1314 and the last in 1486. There are,

however, significant breaks in the text between these two dates. After 1348,

the record becomes confused and is largely incomplete. The regular

recording of court business is resumed in a consistent fashion only after

1371. A largely unbroken sequence is then maintained until 1414 when the

record again falls silent until 1451. After 1458, it ceases once more and is

revived only by a series of fragmentary recordings of business between 1471

and 1486. The function of the register underwent changes during the course

of the fourteenth century. Before the interruption in the mid fourteenth

century it served as a general record of both the civil and criminal business

of the court and the annual visitations conducted in the officiality. However,

from 1371 onwards, it was turned increasingly into a log of fines and

excommunications, although a number of indirect references show that the

official continued to hear civil actions and to conduct visitations.17 The

official exercised jurisdiction as the abbot's alter ego over Cerisy itself, the

villages of Deux-Jumeaux, Littry and Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer together with

the surrounding area. The area was a largely rural one with some industry

associated with the fulling of cloth, with markets certainly being held at

Cerisy and outside the officiality at Saint-Lo.18 A number of households

principally at Cerisycontained servants, some of whom were presented for

16

The manuscripts were deposited in the Archives De partementales de la Manche. H1407, a

manuscript of 87 folios bearing the title `Registrum curie officialis Cerasiensis', was published in

1880, while H1408, a small book of 12 folios, was published in 1935 (Registre de l'officialite de Cerisy,

13141457, ed. M. G. Dupont (Me moires de la Societe des Antiquaires de Normandie, 3e ser., x, Caen,

1880); `Un fragment de registre de l'officialite de Cerisy (147486)', ed. P. Le Cacheux, Bull. Soc.

Antiquaires de Normandie, xliii (1935), 291315. All references to Dupont's edition are to paragraph

numbers unless shown otherwise.) Sections of later 15th- and early 16th-century register noted in

the edition of the later 15th-century fragments were never published and, like the other

manuscripts, did not survive the destruction of the archive in June 1944 (`Fragment', p. 294;

`Re pertoire des bibliothe ques et archives de la Manche', Revue du de partement de la Manche, iv (1962),

403, 410). Material from the register has been used to provide statistical comparisons with a study of

its sister peculiar of Montivilliers (J.-L. Dufresne, `La de linquance dans une re gion en guerre:

Harfleur-Montivilliers dans la premie re moitie du xvi sie cle', Actes du 105e congre s national des socie te s

savantes (Caen, 1980), tome ii, Questions d'histoire et de dialectologie Normande (Paris, 1984), pp. 82, 183 n.

22, 184 nn. 25, 27, 30, 185 n. 33).

17

A. J. Finch, `Crime and marriage in three late medieval ecclesiastical jurisdictions: Cerisy,

Rochester and Hereford' (unpublished University of York D.Phil thesis, 1988), pp. 22f.

18

Crops (Registre, 44, 104a, 147, 173d, 365e, 366h, 387b, 390, 392a, 394f); livestock and poultry (26b,

50c, 55, 134, 392k, 393d, h; `Fragment', p. 298); fulling (Registre, 259a, b); markets (3, 62a, 134, 158, 229bis,

270, 276c, 366a, 392h, 416i, k).

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

254

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ges

immorality.19 A very rough estimate places the population in the region of

6,300, but as with all medieval statistics there must be a wide margin of

error present in this calculation.20 The number of hearths per villageon

which this calculation is basedmay prove to be a better indicator of the

relative sizes of Cerisy, Littry and Deux-Jumeaux. In this case Cerisy would

head the list with 212 hearths in the later fourteenth century, followed by

Littry with 160 and Deux-Jumeaux with fifty. It should, however, be noted

that these figures themselves were calculated indirectly from the amounts

paid on the hearths in the villages of Couvains and Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer.21

As with any other record of criminal activity, there must always be an

unquantified `dark figure' of crime: offences which went unreported or were

settled before another jurisdiction or by other means. At Cerisy, the official

did not exercise his jurisdiction over civil and criminal matters in isolation:

ecclesiastical and lay courts existed to challenge his authority. The king's

court at Bayeux and the seneschalsy of `Mondreville' (Mondrainville?) lay

beyond the area of the officiality, while the official of the bishop of Bayeux

controlled an external ecclesiastical jurisdiction which co-operated with the

Cerisy court on at least two occasions. However, attempts made to summon

individuals living within the peculiar to appear before the bishop's court

proved to be a source of occasional discord. Within the officiality, the court

of the seneschal of Cerisy formed a rival local, secular jurisdiction with its

own officers and a prison. Relations between the two courts were not always

harmonious.22

As with other ecclesiastical jurisdictions, the competence of the court at

Cerisy to deal with what would now be termed criminal offences resulted

from their falling into one of two categories: according to the nature of the

19

Registre, 25d, 131, 298c, 366h, 392k; `Fragment' p. 296. 8 female and 3 male servants were involved

in sexual offences between 1314 and 1346 (Registre, 25d, 43b, 73c, 96c, d, 133c, 138c, d, 168c, 199b).

Among these, a man was specifically described as famulo elemosine and a woman as construeria. In

addition to these, another woman was described as forestaria (25f). Other men who appear were a

public notary, a former clerk of the priory of Deux-Jumeaux, a lodger (locotore) and 2 foresters (60a,

72b, 96b, 117, 195). After 1371, 1 male and 3 female servants appear in connection with sexual

morality offences (298c, 366h, 387f; `Fragment', p. 302).

20

This figure is partly based on Dufresne's calculation of the number of households in Cerisy,

Littry and Deux-Jumeaux and on monne age (hearth tax) returns which survive for other parts of the

officiality between 1368 and 1419. (These may be found in M. Nortier, `Contribution a l'e tude de la

population de la Normandie au bas Moyen-Age (XIVeXVIe sie cles): Inventaire des roles de fouage

et d'aide. Premie re se rie: Roles de fouage paroissiaux de 1369 a 1419', Cahiers Le opold Delisle, xix

(1970), 192. A multiplier of 4.5 was employed to give a rough estimate of population size. One wellknown demographic historian of late medieval Normandy cautions against the use of hearth tax

returns to establish population sizes rather than population densities (G. Bois, The Crisis of Feudalism:

Economy and Society in eastern Normandy, c.13001550 (Cambridge, 1984), pp. 335, 379, 162 n. 52).

21

J.-L. Dufresne, `Les comportements amoureux d'apre s les registres de l'officialite de Cerisy

(xive-xve s.)', Bull. Phil. & Hist. du Comite des travaux historiques et scientifiques for 1973 (Caen, 1976), 132

and n. 5.

22

Registre, 106, 109a, 162, 207b, 218, 230, 309c, 383a, 384a: `Fragment', pp. 300, 313f. On one occasion

the individuals cited were in fact subject to the bishop's jurisdiction (Registre, 383r). Co-operation

occurred when a cattle thief was returned from the king's court at Bayeux, and when the bishop's

court heard an appeal from Cerisy in a marriage suit (Registre, 55, 175).

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ges

255

offence (`ratione materiae') or the ecclesiastical status of those involved

(`ratione personae').23 Matters dealt with in the former category included

fornication and adultery, heresy and blasphemy. In the latter, the ecclesiastical status of individuals ensured that a range of offences usually dealt with

by secular jurisdictions could appear before an ecclesiastical court. Records of

ecclesiastical jurisdictions usually contain little material connected with

violence and those incidents which do appear are generally limited to attacks

on priests or the desecration of holy places. Moreover, such cases are usually

very much the minority when placed in the context of the overall business of

these jurisdictions. The court at Cerisy is unusual in having tried large

numbers of cases relating to physical violence, particularly in the period

following 1371 when actions involving violence, principally assaults, outnumber those for fornication and adulterythe usual staple of the church

courts (see Table 1). Only a handful of these examples of violence had any

connection with a priest or desecration.

Rape and matters relating to abortion and infanticide could be jurisdictionable before a church court, but the preponderance of cases relating to

other forms of physical violence at Cerisy can be best explained by the nature

of the court's constituency. While a few priests appear in connection with

physical violence, it is clerksmen in the lowest grade of holy orderswho

appear most often. Their presence at Cerisy does not make any findings

unrepresentative or, indeed, incompatible with those taken from studies of

secular jurisdictions. Clerks, although required to wear appropriate clerical

garb and to be tonsured, lived as laymen and were able to marry under most

circumstances. They were recruited in such numbers that they would have

been drawn from a wide range of occupations, and at Cerisy clerks can be

found working as craftsmen, servants or engaged in agriculture or stockkeeping.24 Men received the tonsure in order to escape royal taxation in

Normandy and also, no doubt, as a form of insurance against the harsh

penalties inflicted by the secular courts in criminal cases. Many of the

criminals and delinquents tried before the officiality of Bayeux were clerks,

and in later medieval Paris both bona fide and pseudo-clerks formed a distinct

23

The court at Cerisy also held the rights of secular haute justice, but the relevant registers were

destroyed with the rest of the archive (`Re pertoire', p. 403). The nearby abbey of Montivilliers in the

Caux region of Normandy retained a residual secular jurisdiction into the latter half of the 15th

century, although this could then only be exercised in respect of crimes committed during the

octave of the feast of the Holy Cross (J. R. Sweeney, `High justice in 15th-century Normandy: the

prosecution of Sandrin Bourel', Jour. Medieval Hist., x (1984), 295313). Likewise in Paris a number of

ecclesiastical institutions held rights of seigneurial jurisdiction. They tried many brawls with blood

as a result of this secular jurisdiction (B. Geremek, The Margins of Society in Late Medieval Paris, trans.

J. Birrell (Cambridge, 1987), pp. 5760).

24

The accounts of the bishop of Rouen show that 1,642 tonsures were performed between Dec.

1390 and June 1392, and in Normandy from 1409 to 1413, 14,484 men acquired clerical status. At

Montivilliers in the Caux region, 42 men received the tonsure in 1386 and the late 15th-century

fragment of register records the tonsuring of 36 men by the abbot of Cerisy on Easter Saturday 1476

(Geremek, p. 137 n. 8; L. R. Delsalle, `La fin du moyen-a ge' in Diocese de Rouen-Le Havre, ed. N. J.

Chaline (Histoire des dioce ses de France, v, Paris, 1976), p. 56; Dufresne, `La de linquance', p. 182 n. 14;

`Fragment', pp. 314f).

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

256

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ges

criminal grouping. The material from Cerisy is further distinguished by the

full and detailed way in which the incidents are often described. The almost

tangible quality of many of the descriptions of the injuries inflicted on

victims allows a profile of violence to be built up: an opportunity largely

denied to students of homicide and assault in medieval England.

The principal emphasis in what follows will be upon the 323 assaults and

fights recorded between 1314 and 1458. The small size and fragmentary nature

of the later fifteenth-century material make it statistically suspect, and it has

been excluded from the calculations, although specific examples will be

drawn from it. The aim will be to study the material with a view to

establishing the characteristics of violence, the motives behind its use, the

geographical origins of those involved and attitudes to its punishment. The

results will then be compared with those derived from studies of English

homicide and the theoretical models relating to medieval society.

The details of individual cases of assault tend to vary at Cerisy.

Descriptions of assaults and fights from the mid and later fifteenth century

and (more importantly) the early fourteenth century are sparsely detailed in

comparison with those found between 1371 and 1414. By focusing on those

descriptions which survive between these two dates, it is nevertheless often

possible to gain a vivid insight into the extent and nature of the violence

employed. The clear pattern which emerges is one in which the violence was

generally of a mild nature, and far from life-threatening. The typical assault

or fight was conducted without recourse to weapons with one or two blows

to the face or body with the fist or sometimes with the foot. Assailants would

occasionally employ unusual methods of attack: victims were variously bitten,

scratched, jabbed in the face with the finger ends or taken by the ears or the

chin.25 The record is, however, punctuated by a series of incidents in which

serious injury was done to the victim or his life placed in danger. These

formed a hard core of violence involving serious mutilation (in one case

forcing the amputation of a man's forearm), or considerable loss of blood.26 In

some of these instances victims were incapacitated for long periods of time.27

Several incidents were also characterized by an obvious lack of restraint on

the part of the assailant: multiple blows were struck or a variety of potentially

lethal weapons used.28 In the early fourteenth century there were perhaps

four such cases; between 1317 and 1414 there may have been twenty-eight. In

the middle years of the fifteenth century seven of the thirty-three acts seem

to merit inclusion in this category.

Although overall the use of weapons was low, the proportion does vary

from one period to another. In the early fourteenth century, only two per

25

Registre, 348, 384e (biting); 365l (scratching); 366e (jabbing); 375i (taken by the ears); 339c, 363b,

367e, 390m (taken by the chin); 392g (taken by the forelock); 415c (pulled by the nose).

26

See for example, ibid., 232, 262a, 306.

27

See for example, ibid., 315, 366c, 389b.

28

See for example, ibid., 306, 346, 359b, 384o, 387i, 390k.

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ges

257

cent of assaults and fights involved the use of a weapon, though the wide

disparity between this figure and those from later in the century tend to

make it suspect. Likewise, the figure of eight per cent for the period between

1474 and 1485 should be viewed with caution, given the small size and

incomplete nature of the sample. From 1371 until 1414, weapons were used

in a quarter of all assaults and fights. The mid fifteenth century saw an

increase to nearly forty per cent of the total.

Incidents in which weapons were employed were, as would be expected,

on the whole more serious in their consequences than those from which they

were absent. A disproportionate number of armed assaults and fights resulted

in bloodshed or serious andsometimespotentially lethal injury. One

particularly ferocious attack saw the successive use of a staff, a sword and

a dagger against the victim, in addition to the assailant's fists.29 The use of

edged weapons in particular increased the risks to a victim with seven of the

nineteen occasions on which they were employed resulting in serious injuries.

A slightly smaller proportion of blunt instruments produced similar results.

In fairness it should be noted that on several occasions weapons were used in

a restrained or purely intimidatory manner. One woman was threatened with

a knife, but its potential effects were demonstrated upon a piece of cloth

rather than on her person, while one assailant struck his victim across the

shoulders with the flat of his knife and another used his sheathed sword.30

This marked correlation between the presence of a weapon and the

severity of the injuries sustained by the victim is of interest when comparing

the types of weapons used at Cerisy with those employed in homicides in

England. In those cases where the murder weapon can be identified, edged

weapons predominate with knives being especially lethal. Staffs and other

blunt instruments come next, followed by unarmed attacks, though fists and

feet have been misleadingly placed in the category of blunt instruments by

Hanawalt.31 Within the officiality the proportions are reversed. The majority

of incidents did not involve the use of a weapon and where weapons were

used blunt instruments predominate. When added to the potentially fatal

consequences of several of the armed assaults this pattern demonstrates the

important role that the ready use of weaponsand lack of adequate medical

careplayed in increasing the probability that an armed attack would be

transformed into a homicide. The circumstances leading to the death of

Raoul le Juvencel show these factors at work. Raoul was knifed in the

stomach after he had intervened in an argument between two other men. He

was not killed outright, but died several days later, even though he had been

treated by a medicus who had sutured his lacerated bowel.32

Sexual assaults apart, gang attacks were not a typical feature of

Ibid., 408b.

Ibid., 389d, 390a, 394c.

31

Given, pp. 189f; Hammer, pp. 20f; B. A. Hanawalt, `Violent death in 14th- and early 15thcentury England', Comparative Studies in Society and History, xviii (1976), 319.

32

Registre, 308, 309c, d, e, h.

29

30

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

258

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ge s

masculine violence, and the overwhelming majority of male assailants acted

individually. Only twenty-two (seven per cent) of the 323 non-sexual

assaults and fights were group affairs. Forty-five (seventeen per cent)

men were involved out of a total of 274. This can be contrasted with

the pattern found amongst female assailants where group assaults account

for just over a third of the total and involved seven of the twenty female

assailants.33 Men were also able to draw upon a wider range of familial and

non-familial contacts for assistance, appearing with their fathers or brothers

on seven occasions and with non-relatives in a further eleven.34 A further

indication of the wider range of social contacts available to men is

demonstrated by those four cases in which men assaulted their victims

on behalf of a third party; in only one was it clear that this was done on

behalf of a member of the accused's close kin.35

In addition to details relating to the injuries inflicted on victims, the

Cerisy material also affords a rare opportunity to examine the regularity with

which individuals could expect to become involved in violence. This is an

opportunity which is largely denied to the student of homicide. Between

1314 and 1345, the majority of the accused attacked only once.36 Among these,

five were otherwise involved in violence, four as victimsone of whom also

participated in a fightand one as the leader of a gang rape.37 Among the

three men who attacked twice, one also took part in a fight.38 Jean l'Arquier,

the sole representative of the third category, committed an unspecified

number of assaults as well as other crimes and one rape.39 The mid fifteenthcentury period displays a pattern of involvement similar to this.40 A broadly

similar outline is presented between c.1369 and 1414; but important and

subtle changes can be discerned. Again, the majority of men appear once, but

their numbers have declined by ten per cent while an increased proportion

appear as victims or in fights.41 Those individuals who attacked twice have

33

In contrast 6 of the women attacked in the company of their husband or father, and the other

chose the company of one of her husband's relatives (Registre, 114a, 216, 348, 366d, 384f; `Fragment',

p. 299).

34

With a male relative: Registre, 77, 347, 366f 366p, q, 379, 389b, 392m; with a male non-relative:

ibid., 3, 149a, 235a, 339a, b, 366c, 384e, 393r, s, 394r, 410c; `Fragment', pp. 304f.

35

Registre, 392e, 394i, k (on behalf of a brother), m.

36

The number of individuals and their involvement in assaults is as follows: 1 assault, 32 (89%); 2

assaults, 3 (8%); more than 2 assaults, 1 (3%).

37

The 4 who appear as victims are Jean Bernard, Ricard Hequet, Pierre le Paumier and Henri le

Portier, who also became involved in a fight (Registre, 81a, 87a, c, 93b, 141, 148a, 166, 201). Ricard

Quesnel was involved in an attempted rape (ibid., 193, 205).

38

Ingerrand Douin, Guillaume de Nulley and Goret Trublart. The last was involved in the fight

(ibid., 84d, 107, 143c, 171a, 187, 188a).

39

Ibid., 3, 143c, 217.

40

Between 1451 and 1458, 2 of the 28 assailants attacked twice. Another man was otherwise

involved in violence (in a brawl in 1456). The former represent 7% of the total and the latter

individual 4%. None of those who were accused between 1474 and 1485 attacked twice. However,

one man was involved in two successive fights.

41

Frequency of appearance of male accused: 1 assault, 127 (79%); 2 assaults, 22 (14%); 3 assaults, 3

(2%); 4 or more assaults, 9 (6%). Assailants otherwise involved in violence according to the number of

assaults: 1 assault, 37; 2 assaults, 9; 3 assaults, 2; 4 or more assaults, 7.

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ge s

259

increased their share of the total and an added dimension is now present in

the significant minority of men who appear three times or more. These

changes reflect the growing preoccupation of the court with violence during

this period. In the early fourteenth century, the average recorded number of

assaults was roughly two per year. During the later period this had risen to

eight and was considerably higher in certain years. It is interesting to note

that a greater proportion of those who appear twice or more are to be found

in the early fifteenth century, when the annual increase in violence was

particularly marked. Yet even at a period of increased recording of violence

by the court, most men could expect to be involved only once in some act of

physical violence.

Much the same overall pattern is apparent amongst the victims. In the

earliest period, only nine per cent of victims were attacked more than once,

but between c.1369 to 1414 this figure had doubled. Similarly, a greater

proportion of those who fell victim to two or more assaults in this period

were otherwise involved in violence. Only one of the twenty-seven victims

recorded between 1451 and 1458 was attacked twice.42

Something too may be learned about attitudes to violence, principally on

the part of the court, but also occasionally as expressed by individuals. The

severity of an attack was one of the criteria on which the court based its

judgement, and fines tended to increase in relation to the number of blows

struck or the potentially fatal or debilitating effects of the violence. Thus, if a

victim was incapacitated, placed in danger of his life or suffered mutilating

injuries, the appropriate fine would be in the region of forty sous.43 The

effect which different degrees of violence could have upon the sums levied is

shown by three examples from the last decade of the fourteenth century. In

each of these the victims were thrown into the gutter, but the first victim

was taken by his chin as he lay on the ground, the second had his clothes torn

and the third was struck on the head with a staff. The fines imposed on the

That is Guillaume le Secourable (Registre, 410g, 416c). There are no examples between 1474 and

1485. The incidence of assaults on male victims between c.1369 and 1414 was: assaulted once, 123

(79%); assaulted twice, 25 (16%); assaulted 3 times, 5 (3%); assaulted 4 or more times, 3 (2%). Victims

otherwise involved in violence according to the frequency with which they were subjected to assault:

assaulted once, 35; assaulted twice, 14; assaulted 3 times, 4; assaulted 4 or more times, 3.

43

Fines in the Registre are in livres or livres tournois (l./l.t.), sous or sous tournois (s./s.t.), and

deniers (d.). 12 deniers were equivalent to 1 sou, and 20 sous to one livre. 1 franc d'or had an official

value of 20 sous tournois, but the rate varied sharply between 20s. and 36s. over the period 13601423

(P. Spufford, Handbook of Medieval Exchange (1986), pp. 191f.). One man, hired `pro serviendo', was to

receive 6l. for a whole year; another hired out his unspecified services for 15 l.t. for 1 year; a third

apprenticed himself out for 14 months as a wheelwright on condition of receiving 9 francs d'or, a

`good' woollen tunic and a pair of shoes (Registre, 236, 335, 253). For examples of fines for serious

violence see ibid., 363c (30s.: `percussit . . . usque et citra sanguinis effusionem, de quodam ferro equi

in supercillio occulti, taliter [quod] vulnus insecutum fuit'), 366p (40s.: `attroci verberatione et

enormi verberaverat de pedibus et punis super caput et aliis membris, ipsum ad terram

prosternendo, et cutellum suum super ipsum trahendo'), 392g (40s.: `percussit eum pluries de

pugno supra capud, et fecit eum cadere de supra suum equum'), 392p (40s.: `animo malivolo et

crudeliter percussit Johannem l'Escuier de quodam poto stanni semel per capud in gena vel torca

usque ad effusionem sanguinis').

42

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

260

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ge s

assailants differed accordingly with ten sous being levied against the first,

fifteen sous against the second and twenty sous against the third.44 The

presence of blood was also important since the court was careful to note its

absence as well as its presence.45 Attacks in which it was shed were often, but

not invariably, met with a double fine. However, in a significant number, its

presence appears to have had no visible effect on the final outcome. A group

of fines which were imposed on a series of mild assaults in the second decade

of the fifteenth century illustrate these points. At that time, a slap to the face

(`alapa') was usually punished with a fine of five sous, or sometimes less,

while the striking of two blows of this nature raised the fine to 12s. 6d.46 On

one occasion when an alapa resulted in bloodshed, the assailant was punished

with a double fine, but on another, similar occasion, only the standard fine of

five sous was levied.47

The other important criterion which the court emphasized as lending

gravity to an offence was the ecclesiastical status of those involved. Attacks on

priests and other ecclesiastics were met with unusually large fines, which

appear to be out of proportion to the severity of violence involved: a failed

attempt to stab a priest brought the culprit a fine of sixty sous tournois; a man

who drew blood in an assault upon a priest was fined 100 sous tournois at a

period when a similar assault on a clerk brought at most twenty. Another man

was fined twenty sous for throwing a cup of wine in the face of the cantor of

the monastery, but a woman was fined only half this amount for breaking a jar

over a man's head.48 At the beginning of the fifteenth century a man who

struck the clerk of the priest of Deux-Jumeaux in the face by way of retaliation

was fined twenty sous. This was not only substantially more than the usual

penalty, but was five sous more than the fine imposed on the clerk.49 It is

unclear whether acts of violence committed against officers of the court

incurred similar consequences. Most of the examples of this kind are to be

found within the early fourteenth century sections of the register, where the

detail is less complete. They are, however, less than those other fines which

have survived from the same period. The court also punished priestly

delinquencies in this area with considerable severity, though the penalties

were never as severe as was the case when priests were the victims. In the late

fourteenth century a priest was fined twenty sous tournois and twenty sous for

Registre, 363b, 365i, k.

Ibid., 373f, 393i, 404a, 404c, 410a (`absque sanguinis effusione'), 392l (`usque ad effusionem

modicam'), 319, 350 (`ad magnam effusionem sanguinis). At Avignon the presence of blood increased

the gravity of an offence and the severity of its punishment while at Manosques a distinction was

made between its presence or absence when civil damages were awarded (J. Chiffoleau, `La violence

au quotidien Avignon au xive sie cle d'apre s les registres de la cour temporelle', Me langes de l'Ecole

Franc ais de Rome. Moyen Age-temps modernes, xcii (1980), p. 354; R. Gosselin, `Honneur et violence a

Manosque' in Vie prive e et ordre public a la fin de Moyen-Age: Etudes sur Manosque, la Provence et le

Pie mont (12501450), ed. M. He bert (Aix-en-Provence, 1987), p. 55).

46

Registre, 392d, e, h, l (2s. 6d.), 394p (`duas alapas in gena').

47

Ibid., 392i (10s.: `de naso exivit sanguinis'), k (5s.: `naso exivit sanguinis in dentibus').

48

Ibid., 302a, 325 (see for example: 278 (20s.), 279 (20s.t.), 304 (10s.t.), 363q, 375d).

49

Ibid., 370b, c.

44

45

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ge s

261

laying hands on a man and a woman in two separate incidents.50 A clerk might

have expected to receive a penalty of five or ten sous under the circumstances.

In the later half of the next century a fine of fifteen sous was imposed on a

priest.51

The location of an incident could also contribute to its perceived gravity.

A priest who violated his own church in 1485 through an act of bloodshed

had to pay ten livres tournois, and a clerk who laid hands on one of his

fellows within the confines of the abbey was fined 100 sous tournois

considerably more than if the attack had taken place in the street.52 This

attack also took place on a market day which could itself have been an

aggravating factor. A man who struck another lightly on the chest while in

court (`infra metas jurisdictionis nostre') was fined ten sous.53 Other factors

could play a role. The nocturnal nature of an attack was likely to have been

of significance: a single blow to the head at night warranted a fine of twenty

sous, whereas similar attacks in the daytime were met with fines of a quarter

or a half of this.54 A man was imprisonedan unusual occurrence in the

context of crimes against the personafter he had assaulted a man to whom

he had given pledges of peace.55

Though of secondary importance to the actual fact of an act of violence by

or against a clerk, the underlying motive may still have had an effect on the

final punishment. An attack was likely to attract a stiffer penalty if it had

been premeditated. This was one of the factors which ensured that Yves

Anglici was fined sixty sous for ambushing Pierre Siart and striking him on

the head with a stone. The others had been the nocturnal nature of the

assault and Yves's initial perjury.56 However, if an aggressor acted under

undue provocation, or if his actions could in some way be justified, then the

fine might be reduced accordingly. A woman was fined two sous for slapping

a man who called her a whore; her victim retaliated in kind, but had to pay

five sous. Yves de Landes struck Yves Jamez with a tankard because Jamez

had slapped him. He succeeded in drawing blood but was fined the same

amount as Jamez.57 The disparity in the fines imposed on the participants in

other fights would suggest that the court recognized that different degrees of

culpability were involved. A man who threw a suspected thief out of a mill

was fined 2s. 6d., and another man who intervened to prevent a husband

Ibid., 332c, 333a.

`Fragment', p. 303. Other fines from this period were only higher if bloodshed had occurred,

and could be as low as 12d.

52

Registre, 270; `Fragment', pp. 310f. See for example Registre, 363b (10s.), 365i (20s.), 365k (15s.), 366f

(5s.). The abbey church at Cerisy was violated twice during the early 14th century, but the fines

involved were not recorded (ibid., 140b, 212a).

53

Ibid., 365f.

54

Ibid., 384g (5s.: `percuterat de manu per capud ipsius', 385b (`de nocte'), 392e (10s.: `semel de

pugno supra capud').

55

Ibid., 212b.

56

Ibid., 394l.

57

Ibid., 393a, l.

50

51

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

262

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ges

beating his wife paid only two sous. Under ordinary circumstances the nature

of their assaults, in which the victims were thrown bodily to the ground,

would probably have earned them double this amount.58

Individual attitudes too can be discerned occasionally. In 1412 a witness to

an assault felt that the assailant was doing wrong by his actions and in the

same year another bystander considered, perhaps significantly, that an

assailant deserved to be beaten for what he was doing. In both cases, these

comments provoked violent reactions. When Robert des Cageux attempted

to provoke a fight at the house of Ranulph du Bourc, he was told by Jean de

Bapaume that he did wrong to speak and act in such a fashion. These words

only prompted Robert to strike him. Ranulph du Bourc, `seeing these things

and being saddened', told Robert that he was wrong to act in this way. His

objections were also met with violence. On another occasion, when Jean des

Cageux attempted to solicit help to attack Jean de Bapaume in the house of

the curate of Littry, his request fell on deaf ears. Those present said that they

wished his intended victim no harm.59 Not every act of physical violence was

condoned, and a violent response might be considered inappropriate under

certain circumstances or in a particular place.

Motive has been touched upon as a possible factor in determining the

court's response to an incident, and it is clearly of considerable interest

when considering wider questions relating to the characteristics of violence

within medieval society. One problem faced when examining questions of

motive is that the court was principally concerned with the fact of

violence, and with the social standing of those involved, rather than

considerations of motive. This is best shown by those cases in which

victims took immediate action to avenge an assault or were instrumental in

precipitating an attack upon themselves. In these cases all parties involved

were fined for their violent behaviour. Different amounts were levied on

each, in recognition of the varying degrees of culpability and intent, but

the court wasted little time in detailing the precise motives which might

lead to violence. Nevertheless a general distinction was recognized between

violence undertaken with malicious intent (`animo malivolo') and violence

occasioned by anger (`animo irato'), and more precise information is

occasionally revealed.

A complex of factors both recorded and unrecorded would have lain

behind any act of violence and it is difficult to reduce questions of motive to

raw statistics. Certain factors can be isolated. Arguments were the most

common recorded cause, accounting for twenty-six of the incidents. In half

of these some indication is given of the precise nature of the quarrel. These

ranged from a dispute over a wife's use of her husband's goods, to arguments

over quantities of wine (on two separate occasions), a piece of land, a sum of

money, the ownership of a hatchet and an arrow.60 An attempt to lead a man

58

59

60

Registre, 392b, g, 393l, 394f.

Ibid., 393c, f, 394k, r.

Ibid., 217, 392b, g, k, 393b, c.

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ges

263

to a dance against his will degenerated into a fight.61 On two separate

occasions the desire of individuals to reside in the confraternity of SaintMaur against the wishes of others led to violence, as did a dispute over the

right to take the Holy Water around the houses in the parish of Littry.62

Other incidents reveal more in the way of circumstantial detail. Jean Pouchin

was digging in his orchard when Jean le Caruel came up and attempted to

cross a stile. Pouchin told him to get off his land and struck him with his hoe.

Guillaume Poullain was punched on the nose in an argument with Raoul le

Vavassour in a tavern. Raoul had been `moved to wrath' after Guillaume had

tried to drink at the same table. An argument arose between Yves Anglici

and Pierre Siart after Yves had thrown half a loaf of bread through the

window of Pierre's house. The matter did not end there for Yves went off in

search of a sword. He was obviously impatient since he did not go to his own

house, but went instead to the house of Robert l'Oesel and attempted to take

Robert's sword; Robert threw him out. Though thwarted for the minute,

Yves bided his time until nightfall when he ambushed Pierre in an alleyway.

Later in the year, Yves received a thrashing at the hands of his erstwhile

victim.63 Assailants might also act to further the interests of third parties with

one man acting on behalf of his brother, and three others for non-relatives.64

Provocation could take other forms. Attackers reacted to specific slights

upon their characters or sexual reputations, or to an unfavourable comparison with some animal or object in fourteen cases. One such assault led to

immediate retaliation on the part of the victim cum slanderer. In a further

four examples, unspecified `injurious words' led to violence. Another man

was struck after he had insulted his companion's singing. In another case, the

victim had been defending the good name of an absent party in the face of

repeated vituperations.65 Insults could take forms other than words: fights

broke out after one man had spat in another's face and after a man had

laughed at his companion.66 A further five assaults had some connection with

theft or property, and two assaults occurred as men were being led to

prison.67 Surprisingly only two of the accused argued that they had acted in

self defence. In 1321 Henri le Portier, who broke a man's arm with a

swordstroke, claimed that this was justifiable since he had acted to defend

himself. In the same year Jean Rogeri confessed to an assault, but insisted that

he had been defending himself. The court dismissed this defence and fined

him.68

Only a very small number of attacks can be shown to have been

premeditated. The four men who beset a house by night and the man

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

Ibid.,

Ibid.,

Ibid.,

Ibid.,

Ibid.,

Ibid.,

Ibid.,

Ibid.,

392d.

394e, f, p.

363d, 394l, n, q.

392e, 394i, k, m.

394p.

229bis, 392h, i.

93d, 165a, b, 235c, 241b, 365c, 393m, 394f.

87a, b.

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

264

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ge s

who went armed to another's door were acting with a degree of pre-planning

and foresight unusual in the context of ordinary assaults. On a few occasions

men deliberately sought out their victims. Ricard de Landes left his father's

house by night to seek out his chosen victim in the village. On another

occasion Yves de Landes assaulted Jean du Buisson as he was passing before

Yves's house at night. A degree of animosity seems to have existed between

the two families.69 Jean des Cageux came to the house of the curate of Littry

in search of Jean l'Escuier, alias de Bapaume. On entering the house, he

demanded to know where l'Escuier was so that he could `batter him'. An

exchange of words followed and a fight broke out after Jean had been

insulted by l'Escuier. A little before this l'Escuier had fallen victim to one of

Jean's sons Robert, who had come by night to a house where l'Escuier was

drinking in a group. Robert entered the house and beat with his staff on the

table where Jean was drinking, saying, in a suitably timeless phrase, `If anyone

moves, he's dead' (`S'il y a qui bouge il est mort'). He then asked if anyone

wanted to wrestle with him. Jean replied that Robert was wrong to talk and

act in such a fashion; Robert then punched him on the nose. The owner of

the house, Ranulph du Bourc, intervened, saying that Robert had done ill by

this; he was thrown into the fire for his pains.70 Alcohol was at least a

contributory factor in this and a number of other assaults.71

A small number of men werelike Ranulph du Bourcdrawn into

conflicts which were not of their making. One such intervention in an

argument over a sword led to the fatal stabbing of Raoul le Juvencel. The

others had less dramatic consequences. A spreading circle of violence first

enveloped Guillaume Syret, then Sanson Guiart and finally Jean Canonville.

The initial argument had been between Yves Guiart and Guillaume Syret

over a sum of money, during the course of which Guillaume had been

punched in the face. Sanson Guiart then told Yves that he deserved to be

beaten for this. Yves promptly punched Sanson about the head and chest and

turned upon Jean who had been watching these events in silence.72 In a

similar occurrence, Jean l'Escuier was drawn into the conflict between Sanson

de Burgh and Potin de Moultfreart after he had told Sanson that he was

wrong to beat Potin. A further two men intervened in domestic disputes with

violent results. Another man went to his son's aid and the wife of Pierre

Martin was assaulted when she went to her mother's assistance.73

Considerations of revenge motivated only a small number of the attacks.

Four victims took immediate retaliatory action against their attackers, often

Registre, 384g, k, 385b, c.

Ibid., 394k, r.

71

Taverns were the scenes of 2 assaults, in one of which drink clearly played a part (ibid., 392m,

394p). A man was also physically ejected from a tavern by its owner (ibid., 389a). The use of tankards

or other vessels filled with ale, mead or red wine as projectiles or as bludgeons would suggest that

intoxicating drink was an important element in a further 19 acts of violence (ibid., 359b, 363q, 366b,

366m, 384l, 385o, 387a, 389c, 390d, 390l 390o, 390p, 392p, 392p, 393b, 393l, 383b, 394k).

72

Ibid., 393c.

73

Ibid., 242, 384k, 387l, 393f, s.

69

70

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ges

265

repaying with interest the blows that they had received; on another occasion

a man was fined for putting up limited resistance against his two attackers.74

In the later fifteenth century a man unwisely began a fight with two others.75

Other examples were of a more deliberate nature: Yves Anglici was not the

only man to receive a beating at the hands of an erstwhile victim. Philippe le

Pelous attacked Guillaume le Deen in May 1378 after Guillaume had

assaulted him in the previous December.76 In the middle of 1379, Jean

Riqueut and his two sons, Jean and Johennetus attacked Laurent de Alnetis.

In the following year, Jean senior and Jean junior were assaulted by Laurent.77

Ricard de Sallen took part in a gang attack in 1393 on a man who had

attacked him the year before.78 Guillaume le Guilleour threw a stone at a

man who had earlier tried to intimidate his sister and the attack by Yves

Anglici upon Cassin du Molin in 1457 may have been motivated by an

accidental injury to Yves's wife during a game.79 After his fight with Jean des

Cageux, Jean l'Escuier went out with two other men to seek revenge either

on Jean himself or any other member of his family who could be found. This

reliance upon self-help and family ties is most clearly demonstrated by the

conflict which arose between Jean de Tournie res and Jean des Cageux and his

sons during 1412. The cause of this was de Tournieres' assault on a bastard

son of Jean des Cageux. Shortly after this had taken place, Raoul and Robert

des Cageux came successively to de Tournieres seeking to avenge the injury

done to their half-brother. Jean dealt each a blow on the head with his staff.

Some time later Jean and Robert des Cageux dragged de Tournie res and

another man into their tavern. Jean des Cageux struck de Tournie res, saying

that he had done wrong to beat his sons in such a fashion. The innocent

companion received a blow from Robert.80 The court sought to discourage

such informal retaliation and generally fined all those concerned.

Other examples show that deep-seated tensions could exist between

individuals or families at certain times. Jean de Bapaume (alias l'Escuier)

was attacked twice in the same year by members of the des Cageux family. A

flurry of violence also occurred between members of the family du Buisson

and the family de Landes during 1406. Gaufrid and Sanson de Burgh both

attacked the same man during 1408 and Pierre le Guilleour was attacked by

men bearing the same surname in successive years. Gaufrid le Quoquet fell

victim to attacks by Jean Quinot in the July and August of the same year,

Etienne Hervey was also attacked twice by the same assailant.81 Most men

were unfortunate if they fell victim to two assaults in a year from different

assailants.

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

Ibid., 370b, 390k, l, 393l.

`Fragment', pp. 304f.

Registre, 319, 325.

Ibid., 347, 352b.

Ibid., 365m, 366d.

Ibid., 394g.

Ibid., 392m.

Ibid., 344c, 349, 384a, r, 389b.

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

266

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ges

The findings from Cerisy provide an alternative perspective on violence

from that usually provided by the study of English homicide. They can also

be used to modify more general theories which have sought to locate

violence as one of the essentials of medieval society. Some parts of this

alternative perspective match the picture which has emerged from studies of

homicide, while others reinforce the very exceptional nature of homicide

when viewed within a wider context of violent behaviour. Assault within the

peculiar was male-dominateda characteristic of the findings of English

homicideand, as Hammer and Maddern have suggested, the regular use of

violence was limited to a particular group. However, although numerically

significant, most assaults were minor affairs and far from life-threatening.

Some did, however, reach a fever pitch on occasion, and the availability of

weapons and lack of adequate medical care increased the likelihood that such

attacks might cross the all-too-narrow threshold to homicide. The Cerisy

court nevertheless does not appear to have been unduly alarmed by most acts

of violence, so far as one can judge from the amounts levied in fines. It

reflected contemporary views by treating certain acts as more heinous than

others, particularly when they involved ecclesiastics, and it employed a tariff

of fines related to the severity and type of injuries inflicted. Rape and

homicide were, however, dealt with as serious offences, as was theft.82

Individual attitudes may also be discerned, although the evidence for these

is very fragmentary. Violence was not always viewed as a suitable response on

every occasion and in every place, although it was seen as an acceptable

method of punishment or retaliation.

The general theories espoused by Bossy and Muchembled can also be set

against these findings. They give particular weight to the significance of

violencein the form of feudin their theories of the ordering of medieval

society. The opinions of Muchembled on the causes of violent behaviour

within medieval society can be quickly dealt with. Whatever else may be said

for the view that absolutism is good for your mental health since it removes

anxiety, it sits ill with the material from Cerisy. While the polarity of

violence does echo Huizinga's view of a society characterized by extremes, it

is a distant echo. Most violence was mild and certainly not characterized by

fear. Such general psychological explanations seem to have little value in

explaining why a particular minority of individuals should show a lack of

restraint and indeed callousness when dealing with their victims. That their

behaviour was sometimes unrestrained and brutal is not in question, but the

factors which underlay such excesses are harder to fathom, and personal

motivation, experience and predilections must have played their part to an

unknown degree. Finally, Muchembled's contention that violence was

directed against the unknown, against the stranger, away from the isolated

self, appears weak given that violent crime was characteristically parochial at

Cerisy and in other areas.

82

Finch, pp. 215, 225f., 23840.

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ge s

267

Similarly, John Bossy's model of a society faced with the disruptive

influences of kin does not match the pattern of behaviour which emerges

from this jurisdiction. There is no evidence that feud was endemic within the

area or even that it was practised. The internecine violence and pre-emptive

strikes on kin implicit in the term are entirely absent from the record, as are

notions of revenge revolving around the perceived honour of a kin-group.

Far from drawing its source from long-standing and deep-seated enmity,

violence was characterized by spontaneity and lack of premeditation. Where

motives can be established they were often personal, petty and restricted to

an immediate slight or insult: grudge or revenge attacks are the exception

rather than the rule. The choice of weapons does little to dispel the air of

spontaneity which hangs over much of the violence.83 Knives and staffs

would have been carried by men as a matter of course, and other objects such

as stones and household utensils would have come readily to hand. This

impression is further reinforced by some of the unusual objects, such as a key

and a packet of letters, which were pressed into service as makeshift weapons,

and the case of the man who wished to pursue an argument further, but

found that he had left his sword at home.84 The majority of the assaults and

brawls showed a degree of restraint which was unlikely to have placed the

social fabric in jeopardy, though occasionally the violence encountered was

extreme. Furthermore most individuals appear to have been caught up only

once in a web of violence, either as aggressors or victims. Violence was

normally carried out on an individual rather than a collective level, among

men at least and outside the context of sexual assaults. Certain individuals or

family members appear more regularly, but they seem to represent a

particularly violent element in clerical society rather than evidence of

inter-familial conflict.

Such patterns indicate that homicide and feud are aspects of a more

complex phenomenon. The study of homicide and attempts to set a homicide

rate have been encouraged and limited by the nature of the sources and a

preoccupation with a particular set of crimes. What is lacking for England is

provided by Cerisy and other French jurisdictions. The evidence from Cerisy

emphasizes the exceptional and often accidental nature of homicide when

placed against a background of numerous, but mainly petty, acts of violence.

In terms of numbers violence was a pervasive phenomenon within the

officiality. However, it was often of such a mild nature that its actual effect

on the lives of those caught in its web would have been less than would be

assumed if only the raw statistics were available. The homicide of Raoul le

Juvencel was both a rarity and an event of note to judge by the speed with

which details of the fatal stabbing spread through the village and its

83

The categories of weapons employed were as follows: (Blunt Instruments) staffs (21); rods (3);

hurdles (1); faggots (1); tankards (11); cups (4); cussum (2); dishes (1); goblets (1); pots (1); stones (11);

candlesticks (2); jars (1); salt-cellars (1); books (1); letters (1); bows (1), half a loaf of bread (1); keys (1);

(Edged Weapons) swords (6); knives (5); daggers (3); badelarius (1); arrows (1); halberds (1); hatchets (2);

hoes (1); horse irons (1).

84

Registre, 363c (horse iron), 393f (book), 397c (packet of letters), 394l (sword), 410d (key).

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

d:/70-3/47-1.3d 1/9/97 16:4 vk/amj

268

vio l e nce i n t h e m idd le a ge s

vicinity.85 Most individuals could expect to be caught up in violence only

once, but for some such as Raoul le Juvencel, events might conspire to make

this one time too many.

School of East Asian Studies, University of Sheffield

A. J. Finch

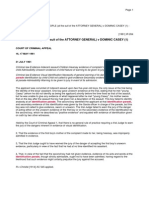

Table 1: Officiality of Cerisy: offences of interest, 13141486

Fornication

Adultery

Assaults

Fights

Blasphemy

Rape

a

b

c

13141346

13701414

14511458

14711486

(13141486)

315a

132

38

8

33

33

220b

24e

2

4

8

2

30

3

35

18

2

10

3

6

(374)

(169)

(298)

(38)

(43)

(8)

An additional charge of fornication arose out of a civil action for marriage.

Includes 5 assaults which occurred between c.1352 and 1370, but which cannot be dated accurately.

Includes 2 fights which occurred between c.1352 and 1370, but which cannot be dated accurately.

85

Registre, 309g, m, n, o; Finch, pp. 224f.

# Institute of Historical Research 1997.

You might also like

- Islamic Bindings PDFDocument248 pagesIslamic Bindings PDFDidem Onal100% (2)

- Postcolonial Approaches To Eastern European Cinema Portraying Neighbours On-ScreenDocument352 pagesPostcolonial Approaches To Eastern European Cinema Portraying Neighbours On-ScreenDidem OnalNo ratings yet

- The Production of Culture Media and The Urban ArtsDocument211 pagesThe Production of Culture Media and The Urban ArtsDidem OnalNo ratings yet

- Mortal and ImmortalsDocument14 pagesMortal and ImmortalsDidem OnalNo ratings yet

- Bruegel and The Revolt of The NetherlandsDocument8 pagesBruegel and The Revolt of The NetherlandsDidem OnalNo ratings yet

- Byzantine Hesychasm in The 14th and 15th CenturiesDocument55 pagesByzantine Hesychasm in The 14th and 15th CenturiesDidem OnalNo ratings yet

- What in A (N Empty) NameDocument24 pagesWhat in A (N Empty) NameDidem OnalNo ratings yet

- A History of ViolenceDocument3 pagesA History of ViolenceDidem OnalNo ratings yet

- The Genealogy of The Editions of The Genealogia DeorumDocument15 pagesThe Genealogy of The Editions of The Genealogia DeorumDidem OnalNo ratings yet

- Facing OthernessDocument19 pagesFacing OthernessDidem OnalNo ratings yet

- Bodrum Ve Milas Çevresindeki Antik Kentlerin Tarihi Co-Rafyas-Na Genel Bir BakDocument32 pagesBodrum Ve Milas Çevresindeki Antik Kentlerin Tarihi Co-Rafyas-Na Genel Bir BakDidem OnalNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Christopher Davis v. Stephen Malitzki, JR., 3rd Cir. (2011)Document13 pagesChristopher Davis v. Stephen Malitzki, JR., 3rd Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Delhi Domestic Working Women's Forum vs. Union of IndiaDocument6 pagesDelhi Domestic Working Women's Forum vs. Union of IndiaPrabhjot KaurNo ratings yet

- Ground Team Member Legal IssuesDocument23 pagesGround Team Member Legal IssuesCAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

- CRIMINAL LAW I NotesDocument36 pagesCRIMINAL LAW I NotesGlorious El Domine100% (1)