Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CST Whitepaper RFID Simulation Tag System Level

Uploaded by

pasquale_dottoratoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CST Whitepaper RFID Simulation Tag System Level

Uploaded by

pasquale_dottoratoCopyright:

Available Formats

WHITEPAPER

RFID AnD WirElEss PoWEr trAnsFEr

siMulAtion FroM tAG to sYstEM

This article discusses the design and modeling of both low frequency (LF) and high

frequency (HF) RFID devices using CST STUDIO SUITE. This can be done at the level of

the individual tag, but also for the entire system, including the reader, the tagged object

and its surroundings. Analyzing the entire system with simulation allows the suitability of

the chosen RFID system for the application to be investigated, and can reveal unforeseen

interactions that can be hard to identify with measurement alone.

OVErViEW

TAG siMulAtion

Radio frequency identification (RFID) makes it possible to catalogue, label and track items quickly in demanding environments. At the heart of all RFID systems is the tag an inductive coil or antenna usually connected to a small microchip.

When interrogated by an RFID reader, this chip generates a

unique data string which allows the tag to be identified and,

if necessary, can provide additional information to the reader.

For the purposes of simulation, RFID systems can be divided

broadly into two groups: low frequency (frequencies up to

tens of megahertz) and high frequency (hundreds of megahertz or greater).

Most RFID tags in common use are passive, which means

that they dont carry any power source. Instead, the power to

run the tag is supplied by the interrogating reader through a

near-field or far-field coupling to the reader. This means that

RFID can be very sensitive to other objects in the environment. Interference and shielding effects can both affect the

performance of tags, and they need to be taken into account

when considering an RFID system. Full-wave EM simulation

can capture the behavior of RFID devices in great detail, making it possible to investigate how a tag will behave without

constructing a prototype.

Figure 1: H-field (left) and surface current density (right) for a typical LF RFID tag.

LF RFID tags are very much smaller than the wavelength of

the reader field. They act as an inductive coil, and couple only

through the magnetic field. Common applications of LF RFID

are animal tagging, industrial process control and smart card

ticketing. These applications do not typically require high data rates, but do need to be very robust.

Since they are electrically small, LF RFID tags are best simulated using the frequency domain solver in CST STUDIOSUITE.

For these tags, simulation can be used to calculate the H-field

and surface currents induced in the coil (Figure 1), and to extract an equivalent circuit for the tag.

CST AG WHITEPAPER RFID SIMULATION FROM TAG TO SYSTEM LEVEL

HF RFID systems on the other hand offer higher data rates

and longer ranges, making them suitable for applications

such as inventory tracking and electronic toll collection. In HF

RFID tags, the coil acts as a normal antenna, usually tightly folded to reduce its area. This means that the impedance

matching in HF RFID tags needs to be carefully optimized to

allow the small antenna to operate efficiently.

HF RFID tags can be simulated using the time domain solver

or the frequency domain solver, depending on the antenna geometry and model size (including the environment).

Useful results when dealing with HF RFID tags include their

S-parameters and their farfields (Figure 2). The farfields can

be used to identify the best position and orientation for

the RFID tags relative to the reader and, using the built-in

Calculate RFID Read Distance macro in CST STUDIO SUITE,

the readable range of the tag can be calculated over the

range of possible angles (Figure 3) given the output power

and sensitivity of the reader antenna.

Most RFID tags include an integrated circuit, which contains

the data associated with that tag. The chip itself will have a

characteristic inductance and capacitance which will affect

the tuning of the antenna, and may also include a matching circuit to improve antenna efficiency. To allow these to

be taken into account by the simulation, CST STUDIO SUITE

also includes a schematic circuit simulation tool which is integrated into the 3D design environment. The 3D model can

be treated as a block and included in a circuit simulation or,

using true transient-circuit co-simulation, the chip can be inserted into the 3D model as a SPICE or IBIS file. A simulation

involving the complex chip impedance is shown in Figure 5.

To improve the efficiency of a tag, these matching circuits can

be tuned using the built-in optimizers in CSTSTUDIOSUITE.

These find the set of parameters for the circuit elements

which best fit a given goal for example, it can find the

component values that minimize the S1,1 of the antenna-chip

combination at the desired resonant frequency.

Optimization is not limited to circuit elements, however. The

dimensions of the 3D antenna model and its material properties can also be parameterized and optimized (Figure 4) in

order to improve its performance. When dealing with very

compact RFID tags, this approach has the advantage that it

can reduce the number of additional circuit elements which

have to be added to the tag during construction.

For example, a parameter sweep or an optimization over the

substrate thickness can be used to adjust the capacitance

and inductance of the antenna and improve its efficiency

without adding an additional matching circuit. Alternatively,

a parameter sweep can be used to investigate how well a

design performs when manufacturing tolerances and deformations are taken into effect (Figure 5).

Z

Theta

Y

Phi

RFID read range

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

-180

-135

-90

-45

45

Theta / degrees

Figure 2: A high-frequency RFID tag (top) and its farfield pattern at its resonant

frequency (bottom).

Figure 3: The read range of the RFID tag in Figure 2.

90

135

180

CST AG WHITEPAPER RFID SIMULATION FROM TAG TO SYSTEM LEVEL

TAG AnD rEADEr siMulAtion

The tag is only half of the RFID system. The reader also needs

to be carefully designed to allow efficient, reliable scanning.

Because RFID readers can be very sensitive to the distance,

position and angle of the tag, it is often useful to be able to

calculate the systems behavior for numerous different positions and orientations quickly. With CSTSTUDIOSUITE, the

tag and the reader can be modeled together in the same simulation. The tags coordinates can be easily parameterized,

and a parameter sweep offers a straightforward way to analyze the effect of misalignment on the tag.

Figure 6 shows how different alignment problems affect the

behavior of an RFID-based NFC system. These planar coils

turn out to be very sensitive to small changes in the position

of the tag relative to the reader, but are more resilient to angular changes. Moving the tag by 10 mm either perpendicular

or parallel to reader causes the output power to drop almost

to 0 mW, but the effect of rotating the tag on the reader is

relatively small.

For this, the Optenni Lab tool is ideal. Optenni Lab shares a

close two-way link with CST STUDIO SUITE, allowing simulation results and circuit models to be shared between the

two products. The matching circuits can then be optimized

to get a good match across a wider range of frequencies, and

the effect of the optimized circuits can be included directly in

a new 3D simulation.

The inclusion of circuit simulation tools means that the analysis can be more detailed than a simple S-parameter calculation. The electronic components of the chip and reader can

be combined with a 3D model of the system (Figure 7), and

using the AC Task, a realistic data transmission can be simulated. This will take into account distortions to the signal

caused by modulation and demodulation, reection within

the system, and unwanted parasitic effects such as interference from other tags.

Improving the efficiency of the link between the reader and

the tag requires a multi-port matching circuit optimization.

The chips used in RFID tags often have frequency-dependent impedance profiles with both real and imaginary parts,

which means that a broadband optimization is required. In

addition, matching the coils at a single position will cause as

many problems as it solves strong mismatches will occur

when the antennas are moved. Together, these two factors

make effective matching difficult.

0,0

S [Magnitude in dB]

S [Magnitude in dB]

-5

-0,2

-10

-0,4

-15

-0,6

-20

-0,8

-1,0

-1,2

r = 2.5 mm

r = 12.5 mm

r = 5 mm

r = 15 mm

r = 7.5 mm

r = 17.5 mm

r = 10 mm

r = 20 mm

-25

-30

-35

0,2

0,4

0,6

0,8

1,2

1,4

1,6

1,8

Frequency / GHz

1,2

1,22

1,24

1,26

1,28

1,3

1,32

1,34

1,36

1,38

1,4

Frequency / GHz

r = 5 mm

r = 6 mm

r = 7 mm

r = 8 mm

r = 9 mm

r = 10 mm

r = 11 mm

r = 12 mm

r = 13 mm

r = 14 mm

r = 15 mm

r = 16 mm

r = 17 mm

r = 18 mm

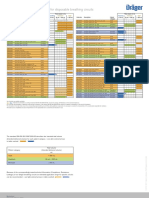

Figure 4: (top) A parameterized antenna model. (bottom) The S-parameters

Figure 5: (top) A bent RFID tag model. (bottom) The S-parameters from a pa-

from a parameter sweep over the arm length r, not taking complex chip im-

rameter sweep over the radius of curvature, taking into account the complex

pedance into account.

chip impedance.

CST AG WHITEPAPER RFID SIMULATION FROM TAG TO SYSTEM LEVEL

Distance between the coils

Oset of one coil against another

30

25

25

Output power / mW

30

20

15

10

15

10

20

10

15

20

25

30

-15

-10

-5

Distance / mm

10

15

60

75

90

Out-of-plane rotation

30

30

25

25

Output power / mW

Output power / mW

In-plane rotation

20

15

10

20

15

10

Offset / mm

-90

-45

Rotation angle / degrees

45

90

15

30

45

Tilt angle / degrees

Figure 6: The effect of different possible alignment problems in a 13.56 MHz RFID-based near-field communication (NFC) system.

CST AG WHITEPAPER RFID SIMULATION FROM TAG TO SYSTEM LEVEL

2

15 V

AM Signal Generator

1.0e3 n

200

1.0e3 p

antenna_input

HF

1000

1000 p

(b)

N:1

20

5

Input

TAG_1

1n

(a)

20

1 SPICE 3

50

nfet

1.4 p

1n

TAG_1

20

TAG_4

2

3

TAG_3

3

anode

1.4 p

20

LP-Filter

Filtered_Envelope

(d)

30 n

Demodulator

50

30 n

HF_eliminated

21 p

21 p

(a) Input

100 p

(b) Modulated signal

0,01

0,00

10

-0,01

-0,02

Voltage / V

Voltage / V

ideal_diode

cathode

Diode

0.001 n

62.75 n

50

12

(c)

SPICE

6

4

-0,03

-0,04

-0,05

-0,06

-0,07

0

-2

-0,08

-0,09

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

50

100

Time / ns

(c) Received Signal

6E-05

150

200

250

300

Time / ns

(d) Filtered signal

8E-06

7E-06

4E-05

6E-06

Voltage / V

Voltage / V

2E-05

0E+00

-2E-05

5E-06

4E-06

3E-06

2E-06

-4E-05

1E-06

-6E-05

0E+00

50

100

150

Time / ns

200

250

300

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

Time / ns

Figure 7: Schematic view of a full tag-and-reader simulation, showing the time-domain signals at various points throughout the system. The 3D model is the large block

on the center-right.

CST AG WHITEPAPER RFID SIMULATION FROM TAG TO SYSTEM LEVEL

Full sYstEM siMulAtion

Figure 8 shows one example: sixteen pill boxes marked with

RFID tags, all located in close proximity. These tags are interrogated by a reader located some distance away. Figure

9 shows the S-parameters for one tag on each row, ordered

from those nearest to the antenna to those furthest away.

The simulation reveals that the RFID tag in the first row,

which is closest to the antenna, are actually more weakly

coupled than the RFID tags located in the center of the pallet, due to constructive interference. This effect would be

extremely difficult to calculate without carrying out a fullwave simulation.

It is not enough for an RFID tag to work in isolation. Any

practical RFID application also needs to take into account the

effect of the environment, including detuning, shielding, and

coupling between tags. These effects can have many different possible sources, including other tags, metal structures,

nearby people and animals, and the tagged object itself.

Simulation is the only way to calculate these complex effects

before the prototyping phase begins.

Figure 8: A pallet containing multiple RFID-tagged pill boxes (left), close to a reader (right).

S [Magnitude in dB]

-40

-45

-50

-55

-60

-65

-70

-75

-80

1st row

2d row

-85

3rd row

4th row

-90

0,8

0,85

0,9

0,95

Frequency / GHz

Figure 9: S-parameters calculated for one RFID tag on each row.

1,05

1,1

CST AG WHITEPAPER RFID SIMULATION FROM TAG TO SYSTEM LEVEL

Another situation where a full simulation is useful is shown

in Figure 10. Here, the RFID tag is embedded in a complex

metal environment, consisting of several spools of a cable

contained in a crate reinforced by a metal cage. All this metal will shield the RFID tag, which means that it may only be

readable in certain directions or worse still, not at all.

A full-wave simulation of the system can calculate the farfield of the RFID tag (Figure 11) in order to find the transmission peaks and nulls, to allow the engineer to decide where

the best location for the reader antenna is. When compared

to Figure 2, it is evident that the environment has altered the

tags farfield drastically.

Figure 10: A RFID tag on a spool of cable in a reinforced crate.

Figure 11: The farfield of the RFID tag in situ. Red areas indicate transmission peaks.

The time domain solver in CSTSTUDIOSUITE supports GPU

computing, which can dramatically speed up the simulation

of large or complex models. This makes it possible for big

sections of the environment to be simulated and, especially

when combined with distributed computing (DC) for solving

systems with multiple tags, can be a very useful extension to

the simulation tool.

CST AG WHITEPAPER RFID SIMULATION FROM TAG TO SYSTEM LEVEL

Conclusion

Traditional RFID design methods can be complemented by

EM simulation in order to better understand the behavior of

the device. Parameterization and optimization means that

multiple design variations can be investigated as part of a

what-if analysis, and the antennas can be tuned and matched

for better efficiency. The whole system can also be simulated, including the reader, multiple tags, and the devices surroundings, allowing engineers to examine how the system

will behave in a realistic environment. These environmental

effects can be very hard to detect without using simulation.

Author

Marc Rtschlin, Market Development Manager for Microwave and RF Applications, CST AG

About CST

Founded in 1992, CST offers the markets widest range of

3D electromagnetic field simulation tools through a global network of sales and support staff and representatives.

CST develops CSTSTUDIO SUITE, a package of high-performance software for the simulation of electromagnetic fields in all frequency bands, and also sells and supports complementary third-party products. Its success

is based on a combination of leading edge technology,

a user-friendly interface and knowledgeable support

staff. CSTs customers are market leaders in industries

as diverse as telecommunications, defense, automotive,

electronics and healthcare. Today, the company enjoys a

leading position in the high-frequency 3D EM simulation

market and employs 280 sales, development, and support personnel around the world.

CST STUDIO SUITE is the culmination of many years of

research and development into the most accurate and

efficient computational solutions for electromagnetic

designs. From static to optical, and from the nanoscale to

the electrically large, CSTSTUDIOSUITE includes tools for

the design, simulation and optimization of a wide range

of devices. Analysis is not limited to pure EM, but can also

include thermal and mechanical effects and circuit simulation. CSTSTUDIO SUITE can offer considerable product

to market advantages such as shorter development cycles,

virtual prototyping before physical trials, and optimization instead of experimentation.

Further information about CST is available on the web at

https://www.cst.com

Trademarks

CST, CST STUDIO SUITE, CST MICROWAVE STUDIO, CST EM STUDIO, CST PARTICLE STUDIO, CST CABLE STUDIO, CST PCB STUDIO, CST MPHYSICS STUDIO, CST MICROSTRIPES,

CST DESIGN STUDIO, CST BOARDCHECK, PERFECT BOUNDARY APPROXIMATION (PBA), and the CST logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of CST in North America,

the European Union, and other countries. Other brands and their products are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective holders and should be noted as such.

CST Computer Simulation Technology AG, Bad Nauheimer Str. 19, 64289 Darmstadt, Germany

You might also like

- Chapter 4: Boundary Conditions: Introduction To ANSYS HFSS For Antenna DesignDocument28 pagesChapter 4: Boundary Conditions: Introduction To ANSYS HFSS For Antenna Designpasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- The Early Hystory of Sring Theory and SpersymmetryDocument13 pagesThe Early Hystory of Sring Theory and Spersymmetrypasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- AN3 MLX90129 Antenna DesignDocument8 pagesAN3 MLX90129 Antenna Designpasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- A Floquet-Bloch Decomposition of Maxwell's EquationsDocument30 pagesA Floquet-Bloch Decomposition of Maxwell's Equationspasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- Theory of Non Linear Dynamical Systems PDFDocument44 pagesTheory of Non Linear Dynamical Systems PDFpasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- Gain Measurement of Antenna Using RFIDDocument4 pagesGain Measurement of Antenna Using RFIDpasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- RFID Simulation With ANSYS Electronics DesktopDocument34 pagesRFID Simulation With ANSYS Electronics Desktoppasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- Data SheetDocument2 pagesData Sheetpasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- Promo Magicstrap RfidwhitepaperDocument7 pagesPromo Magicstrap Rfidwhitepaperpasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- WS02 2 Microstrip WaveportsDocument21 pagesWS02 2 Microstrip WaveportsarksrameshNo ratings yet

- HF Antenna Design PDFDocument24 pagesHF Antenna Design PDFpasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- Agilent 4286A SpecsDocument20 pagesAgilent 4286A Specspasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- Modern RF and Microwave Measurement Techniques PDFDocument476 pagesModern RF and Microwave Measurement Techniques PDFYuliyan TopalovNo ratings yet

- HF Antenna Design PDFDocument24 pagesHF Antenna Design PDFpasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- 14 2 Hfss-Ant Hfssie Rcs WsDocument11 pages14 2 Hfss-Ant Hfssie Rcs Wspasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- Note On HFSS Field Calculator PDFDocument34 pagesNote On HFSS Field Calculator PDFpasquale_dottorato0% (1)

- Technical Guide of QUCSDocument264 pagesTechnical Guide of QUCSpasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- The Fourier Transform and Its ApplicationsDocument428 pagesThe Fourier Transform and Its Applicationsmachinelearner100% (3)

- TTWBDocument5 pagesTTWBpasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- Non Destructive Dielectric Measurements and Calibration For Thin MaterialDocument9 pagesNon Destructive Dielectric Measurements and Calibration For Thin Materialpasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- Thesis ShenDocument97 pagesThesis ShenMatt KrausNo ratings yet

- Thesis ShenDocument97 pagesThesis ShenMatt KrausNo ratings yet

- MonzaR6 TagChip Datasheet 20141209 R3Document21 pagesMonzaR6 TagChip Datasheet 20141209 R3pasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- Pagina 1 Di 2 Powerid: Pioneer and Leader in The Field of Battery-Assisted, Passive RfidDocument2 pagesPagina 1 Di 2 Powerid: Pioneer and Leader in The Field of Battery-Assisted, Passive Rfidpasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- AppNoteSAN206B Using EM Analysis For RFID Antenna DesignDocument31 pagesAppNoteSAN206B Using EM Analysis For RFID Antenna Designpasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- Integra Overview 20150929 R1Document4 pagesIntegra Overview 20150929 R1pasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- Vector and Tensor AnalysisDocument221 pagesVector and Tensor Analysispasquale_dottorato100% (1)

- Iso14443-4 (2001)Document42 pagesIso14443-4 (2001)pasquale_dottoratoNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- F01 Rear Seat Entertainment SystemDocument28 pagesF01 Rear Seat Entertainment SystemPhan Văn0% (1)

- Light SPEARDocument2 pagesLight SPEARКатя ПрохороваNo ratings yet

- COMS2Document490 pagesCOMS2Mora JoramNo ratings yet

- MT6167 MediaTekDocument39 pagesMT6167 MediaTekEdmilson Lanes RamosNo ratings yet

- (The Electromagnetic Spectrum) : Using WavesDocument44 pages(The Electromagnetic Spectrum) : Using WavesSam JordanNo ratings yet

- Financial Bid Opening Record (Muchulka)Document4 pagesFinancial Bid Opening Record (Muchulka)nitish JhaNo ratings yet

- MCM 27798Document27 pagesMCM 27798Arben NgarangadNo ratings yet

- Microstrip AntennasDocument13 pagesMicrostrip AntennasIgor CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Asiasat 4 PlanDocument1 pageAsiasat 4 PlanSha LeNo ratings yet

- Cell Phone Jammer: By:-Ganesh Pathak Pallavi Mantri Rohit Patil Pawan KumarDocument16 pagesCell Phone Jammer: By:-Ganesh Pathak Pallavi Mantri Rohit Patil Pawan KumarvishalsinghvivekNo ratings yet

- Wideband Transmitters: Aggressive On Passive InterferenceDocument2 pagesWideband Transmitters: Aggressive On Passive InterferenceBubu Keke CacaNo ratings yet

- Abbreviations and TerminologyDocument15 pagesAbbreviations and Terminologyphuong leNo ratings yet

- Budget Studio Equipment List: Microphones Under £25Document1 pageBudget Studio Equipment List: Microphones Under £25Rory SteelNo ratings yet

- TG043 Figure8 Install GuideDocument14 pagesTG043 Figure8 Install Guidemazen zaloudNo ratings yet

- 6 - Broadcasting MCQ QuestionsDocument10 pages6 - Broadcasting MCQ QuestionsMohamed AlfarashNo ratings yet

- 3G JIJIGA VOICE+DATA CLUSTER ReportsDocument22 pages3G JIJIGA VOICE+DATA CLUSTER ReportsHawe MesfinNo ratings yet

- RRU5519et Hardware Description Draft B PDF - enDocument30 pagesRRU5519et Hardware Description Draft B PDF - enKateNo ratings yet

- JSS-296 - NCR-333 - Ton SART20 - Tron 40SDocument401 pagesJSS-296 - NCR-333 - Ton SART20 - Tron 40SBryan MilloNo ratings yet

- FAQs on Wireless Licensing in IndiaDocument15 pagesFAQs on Wireless Licensing in IndiaNitin Jain100% (1)

- HVE Question BankDocument27 pagesHVE Question BankArpit MehtaNo ratings yet

- Recommended Application Area For Disposable Breathing Circuits - 9103318 - enDocument2 pagesRecommended Application Area For Disposable Breathing Circuits - 9103318 - enMuh. NUZUL NURMUSLIMNo ratings yet

- 365 V 1Document448 pages365 V 1Lavern SipinNo ratings yet

- DBX 231 S Data SheetDocument2 pagesDBX 231 S Data Sheetryan_pashyaNo ratings yet

- Aeronautical Propagation Model Guide V2Document14 pagesAeronautical Propagation Model Guide V2oldjanusNo ratings yet

- Sepura DMR Family BrochureDocument2 pagesSepura DMR Family BrochureRod MacNo ratings yet

- The Physical Layer of The Universal Mobile Telecommunications SystemDocument7 pagesThe Physical Layer of The Universal Mobile Telecommunications SystembinoNo ratings yet

- ALTIMETRDocument527 pagesALTIMETREleazarNo ratings yet

- Wireless Doorbell Using ArduinoDocument13 pagesWireless Doorbell Using ArduinoPraveen Kumar pk60% (5)

- RC Phase Shift OscillatorDocument3 pagesRC Phase Shift OscillatorF.V. JayasudhaNo ratings yet

- Philips PF7835 193618Document2 pagesPhilips PF7835 193618Afonso AlvesNo ratings yet