Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Work Health and Safety Law

Uploaded by

SnoopOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Work Health and Safety Law

Uploaded by

SnoopCopyright:

Available Formats

200799: Work Health and Safety Law

Spring 2015

The Law of Workplace Safety

Page 1 of 10

200799: Work Health and Safety Law

Spring 2015

Table of Contents

Module 1

Issues in Work Health and Safety Law

Module 2

Workplace Safety under the Common Law and Employment Law

Module 3

History and Development of Work Health and Safety Law

Module 4

Work Health and Safety Regulatory Framework in Australia

Module 5

Primary Duty of Care

Module 6

Upstream and Controllers Duties

Module 7

Duty to Consult

Module 8

Regulations, Codes of Practice and Standards

Module 9

Liability of Officers

Module 10

Duties and Rights of Workers

Module 11

Investigations, Enforcement and Compliance

Module 12

Sentencing and Penalties

Module 13

Workplace Bullying

Module 14

Workers Compensation Law

Module 15

Duty to Rehabilitate

The Law of Workplace Safety

Page 2 of 10

200799: Work Health and Safety Law

Spring 2015

Module 1

Issues in Work Health and Safety Law

Readings:

Johnstone: Chapter 1

Legislation

Work Health and Safety Regulation 2011 (NSW) Part 3.1

1 OVERVIEW

In this module, we will be looking at workplace safety issues in Australia, generally, including:

common workplace injuries;

the basic framework of workplace safety law

the importance of adequate workplace safety from different perspectives; and

some of the challenges that workplaces face in implementing and maintaining safe systems of work.

The law also seeks to protect workers through the criminal law by imposing obligations on employers (and

others who may affect the safety of people at a workplace). The consequences of breaches these legislative

duties vary from improvement notices and on-the-spot fines from a regulator, to large fines and

imprisonment by order of a court. While work health and safety (WHS) (previously, occupational health

and safety or OHS) is often used to describe workplace safety in general, in the legal sphere it is a reference

to the criminal regulation of workplace safety. This is where we will be focusing most of our attention in

this unit.

In Australia, the law provides for the protection of workers through a variety of mechanisms. Under the

common law, employers owe a duty of care to employees. There is also a right under the law of

employment for an employee to refuse to follow a direction from his/her employer where the employee

may be put in danger. There has also been statutory intervention under the workers compensation

legislation to compensate employees for injuries sustained while at work and while travelling to and from

work. Such schemes also encourage the rehabilitation of employees. All of these schemes may be class as

civil law mechanisms.

2 HAZARDS, RISKS AND CONTROLS IN THE WORKPLACE

(a) Hazards and Risks

Workplaces can expose employees to hazards to their health and safety. These hazards, and the extent of

measures to circumvent hazards, will vary from workplace to workplace. For example, the hazards at a

construction site or a mine would be greater than that in the office environment. Injuries are, however,

prevalent in all types of workplaces. Accordingly, all persons conducting a business or undertaking have

duties under WHS law.

It is important at this point to become familiar with common terms when considering workplace safety.

The Law of Workplace Safety

Page 3 of 10

200799: Work Health and Safety Law

Spring 2015

A hazard can be defined as something which has the potential cause harm to a persons health

and safety. This could include substances and work practices.

A risk is the chance or probability that the hazard will lead to harm to a persons health and safety.

A control is a measure adopted to circumvent a risk.

A simple example of the above is a wet floor. The wet floor is a hazard in that it has the potential to cause

an injury if someone were to slip. The chance of someone slipping is a risk. The risk is higher if someone

the wet floor is in a busy area. A control of the risk might be to cordon-off the area or dry the area.

From a legal perspective, the identification of hazards and risk is important. An employer may be liable

under WHS legislation for merely failing to prevent a risk to a persons health and safety (i.e. it is not

necessary for there to actually be an injury).

Many businesses and undertakings in Australia are corporations. In line with trends in others areas of

regulatory enforcement, WHS legislation often imposes obligations directly on directors and managers of

corporations to implement safe systems of work or ensure that their corporation does so.

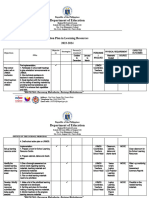

(b) Hierarchy of Controls

At part (a), above, we looked at concept of controlling risks as being measures that an employer will adopt

to circumvent a risk to health and safety. The example of the wet floor is one where control measures are

simple and effective. However, in industries where employees may be exposed greater health risks, control

measures will be more complex. In some cases, it will be almost impossible for an employer to eliminate

a risk. It may be that there is no way of eliminating the hazard. Measures of elimination may be costly

when compared with the risk to health and safety. To eliminate the hazard may impede the ability for

work to be completed. Accordingly, an employer will need to implement a range of measures and

techniques to reduce the risk of an injury. We call this the hierarchy of controls.

The following diagram represents the hierarchy found in Part 3.1 of the Work Health and Safety Regulation

2011 (NSW) (and found in equivalents in other jurisdictions):

The Law of Workplace Safety

Page 4 of 10

200799: Work Health and Safety Law

Spring 2015

This involves eliminating (or substituting) the hazard that gives rise to the risk of injury.

For example, a risk of fall from a dug hole can be eliminated by filling in the hole.

Hazard

Elimination

Elimination

Isolation

This involves removing a person at risk from the hazard. For example, where an

employee is working with high voltage electrical power, switching the power supply off

is a form of isolation.

Engineering Control

Administrative Controls

Administrative controls are primarily directed at workers and how they approach a

hazard. Such controls include training, systems of safe work, rest breaks and rotations.

Worker

Minimisation

This involves using equipment to modify the envirnoment where the hazard is located.

An example of an engineering control would be a barricade around a hole or a noise

muffler.

Personal Protective Equipment

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is used by workers when coming into contact with

a hazard. Examples include safety goggles, flourescent vests and steel-capped boots.

3 SAFE WORK CULTURE

A problem faced in many workplaces is how seriously workplace safety is taken by employers or employees.

While employers may have water tight contracts with employees and contractors and have an array of

safe work procedures and protocols, the extent to which contractors and employees practise a safe system

of work is also a hurdle in ensuring safe work practices.

A workplace that considers safety to be a high priority is said to have a safe work culture. There has been

considerable literature in the field of WHS and human resource management as to implementing such a

culture in workplaces. The following is an excerpt from M Quinlan et al, Managing Occupational Health and

Safety, 2009.

[75-983] Construction industry to tackle safety culture

The Federal Safety Commissioner (FSC) has announced a new and innovative framework to address the

safety culture and tackle the poor safety record of the construction industry. This article by OHS journalist

David West was first published at the CCH website on 26 October 2006.

The Law of Workplace Safety

Page 5 of 10

200799: Work Health and Safety Law

Spring 2015

The framework, A Construction Safety Competency Framework: Improving OH&S performance by creating

and maintaining a safety culture, was developed by the Cooperative Research Centre (CRC) for Construction

Innovation.

When applied, the framework creates a matrix of safety management tasks, safety critical positions and the

necessary safety competencies, collectively aimed at changing the culture of safety. Dean Cipolla, project

leader and John Holland Group safety manager said: The framework is all about culture change even though

it may look like an engineering document.

Over the past three years, the John Holland Group has been the testing ground for the framework, where it

has led to a 25% drop in accident and injury severity. Mr Cipolla is so encouraged by the results to date that

he believes that the framework can become an industry standard.

The FSC has also launched Safety Principles and Guidance A practical guide for improving occupational

health and safety (OHS) in the building and construction industry. This document promotes a level of

commitment to safety that goes beyond complying with legislative requirements, encouraging industry

participants to demonstrate a commitment to sustained improvement in OHS outcomes. The safety principles

and guidance are in keeping with the FSCs commitment to Priority 5 of the National OHS Strategy 2002

2012, which is to strengthen the capacity of government to influence OHS outcomes.

At the launch of the framework on 29 September 2006, Workplace Relations Minister Kevin Andrews called

it a practical tool and a positive way forward for companies wanting to reform the culture of the industry.

For its part, the Australian Government is also supporting OHS research through both the Australian Safety

and Compensation Council and the Office of the Federal Safety Commissioner, both organisations are

represented here this morning, Mr Andrews said.

This is important because, while the construction industrys OHS performance is improving, it is still a

long way short of best practice and too many Australians are still being killed and injured every year. The

2003 Cole Royal Commission found the occupational health and safety performance of the building and

construction industry was unacceptable.

The construction industry makes up 8% of the Australian workforce but accounts for more than 15% of all

fatalities in the workplace. In 20032004, there were 52 traumatic injury deaths within the construction

sector, which represents a 6.7 fatality rate per 100,000.

The office of the FSC was established a little over a year ago with the aim of improving the poor safety

record in the industry. It aims to use the leverage of the Australian Government as a major construction

client to bring about cultural and behavioural change.

The first year for the FSC has been one of consultation and cooperation with both the industry and state and

territory governments. FSC achievements and initiatives include:

the development and implementation of an accreditation scheme for companies contracting for

Australian Government building and construction projects

an investigation of how best to assist subcontractors with a systematic approach to OHS

the development of safety principles and guidance

the commencement of the development of a standardised and comprehensive system for measuring

the Australian building and construction industrys OHS performance.

A focus on culture

Mr Cipolla admitted that the safety record in the construction industry is not very good and said, we are at

a point where we need to see cultural change in the management of safety.

The Law of Workplace Safety

Page 6 of 10

200799: Work Health and Safety Law

Spring 2015

Until now the safety training for staff whether they are unskilled workers, tradesmen or engineers has been

ad hoc stuff by companies. The framework provides a baseline set of cultural and mechanical skills for all

employees.

We have identified the competencies needed by all workers in the industry to perform each safety

management task effectively.

The framework aims to identify staff positions critical to safety and the safety management tasks that need

to be performed well. For example, tenderers can have an impact on safety, as can general managers,

supervisors and tradespeople. Most positions are safety critical.

The framework identifies nine broad staff actions essential to a positive and effective safety culture,

including company values, demonstrating leadership, clarifying required and expected behaviour and

personalising safety performance. The framework then expands and explains these actions and indicates how

they work to influence the safety behaviour of employees and thereby improve overall safety performance.

The CRC claims that the nine actions can be introduced at no direct cost other than the time taken by

executive managers to visit sites.

In total we have identified 39 safety management tasks and have mapped the safety critical positions that

should be performing each activity. These have been formed into a matrix, which is the basis of the

framework, Mr Cipolla said.

For each of the 39 safety critical tasks, the framework lists in detail the steps that should be followed when

completing them, the knowledge and skills required to effectively complete the tasks and the behaviour that

should be undertaken while completing them.

Mr Cipolla pointed out that the framework may not only become the industry standard, but may also be

applied to other industries.

A lack of a safe work culture not only means that employees have higher exposure to risks, it also means

that any systems or procedures on paper are generally not able to be relied upon by employers seeking to

show that they did everything they could to prevent a risk.

4 CRIMINAL REGULATION OF WORKPLACE SAFETY

As noted above, the consequences of breaching WHS duties involving criminal penalties including fines

and imprisonment. While a breach of WHS duties may amount to criminal offences, the actual process of

enforcement has some key differences when compared with traditional offences. In New South Wales,

for example, WorkCover (as opposed to the police) investigate breaches. Prosecutions were, until recently,

conducted in the Industrial Court (as opposed to the Local, District or Supreme Courts). Prosecutions

may be directed against companies (as opposed to only individuals). Unlike most common law offences,

WHS offences are absolute liability (i.e. the commission of a wrongful act is prohibited regardless of the

intention of the offender).

Criminal sanctions are used to regulate the conduct of businesses in a variety of contexts at both the state

and federal level. Examples include:

environmental protection (Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 (NSW));

tax evasion (Taxation Administration Act1953 (Cth));

The Law of Workplace Safety

Page 7 of 10

200799: Work Health and Safety Law

Spring 2015

cartels and market collusion (Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth));

deceptive market practices (Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth));

insider trading (Corporations Act 2001 (Cth));

integrity in financial services (Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth)); and

financial reporting (Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 (Cth));

Breaches of these statutes can result in substantial fines to the company involved. It may also result in the

directors (or those directly involved in the breach) being personally liable to a fine or imprisonment.

A critical question in this subject, which is by no means unique to WHS law, is whether it is in fact necessary

to have a WHS regulatory framework when the law of negligence provides safeguards against unsafe

workplaces and systems of work. As we will see in the next seminar, under the law of tort, an employer

must take reasonable care not to expose its employees to health and safety risks. Similarly, the Work Health

and Safety Act 2011 (NSW) imposes a duty on employers (as persons conducting a business or an

undertaking) to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health and safety of its employees. The two

are not identical duties. The latter is more onerous. Nonetheless, there is a considerable overlap. The law

of negligence has long been recognised to deter undesirable behaviour. Perhaps the leading economic

explanation is provided by Judge Richard Posner in one of his extra-curial works.1 Posner argues that if a

person is made liable for damages for particular conduct, he or she will take greater precautions to avoid

such conduct. Another judge, Judge Guido Calabresi, a proponent of the market deterrence theory,

argued that the costs of accidents will be reduced if the cheapest cost avoider (the person causing the

injury) is made strictly liable to compensate an injured party.2

If the law of negligence protects workplace safety, why is there a need for a criminal law protecting the

same? The differences might be seen in the consequences. In criminal law, a breach of the law gives rise

to a criminal penalty. In civil law, a breach gives rise to an award of damages. As Professor John Coffee

notes, criminal law prohibits whereas civil law prices.3 Accordingly, and in economic terms, civil law

does not seek to stop behaviour but to compensate for the negative aspects of the impugned behaviour.

There are weaknesses with this approach including that the jurisprudence on the negligence in the

workplace continues to regard the duty of employers as an important one and not simply one to

compensate for non-conformance to standards by an employer.

Another potential issue with solely relying on the law of negligence is what Posner identified as being two

crucial ingredients which are also its potential shortcomings.4 First, civil law relies on a victim. In

negligence, the victim must have been injured in order to commence proceedings as negligence is not

actionable per se. Secondly, the only threat is compensation. As we will see from the nature of workplace

risks, often safety incidents will arise due to safety being overlooked in the operation of a business or

undertaking. If the benefits of running a risk-prone workplace (because, for example, it provides greater

output or low overheads) outweigh the risk of compensation, an employer is unlikely to be deterred from

Richard Posner, Economic Analysis of Law (Aspen Publishers, 6th ed, 2003) ch 6.

Cited in Andrew Burrows, Remedies for Breach of Tort and Contract (Oxford University Press, 3rd ed, 2004) 39-40.

3 John Coffee, Paradigms lost: the blurring of the criminal and civil law models and what can be done about it (1991-1992) 101 Yale

Law Journal 1875, 1876.

4 Richard Posner, Economic Analysis of Law (Aspen Publishers, 7th ed, 2007) 292.

2

The Law of Workplace Safety

Page 8 of 10

200799: Work Health and Safety Law

Spring 2015

the law of negligence alone. This suggests that criminal law may have a place. Even if it does, the question

that must then be considered is the extent to which the criminal law should regulate workplace safety.

5 THE IMPORTANCE OF WORKPLACE SAFETY

Workplace safety is an important issue for any business. Poor safety practices can expose workers to injury

and, in some cases, death. Aside from the importance of ensuring that workers are safe, businesses should

treat safety as a priority for the following reasons:

Workplace injuries inevitably lead to less productivity while injured staff member are recovering.

Businesses often measure this through an LTI (lost time in injury). The higher the LTI, the less

productivity (and increase in cost) for the business. It has been estimated that a business (on

average) will lose 10% of its profits due to injuries.

Businesses in todays environment have a high turnover of staff compared with business many

decades ago. Employees move from workplace to workplace. Poor workplace safety can foster a

negative image of the employer.

At a basic level, businesses can be exposed to litigation from injured workers and the families of

deceased workers. While insurance may cover loss arising from litigation, businesses may face

higher insurance premiums where there are frequent injuries leading to compensation claims.

Following the enactment of WHS legislation, businesses can be exposed to criminal liability.

Directors and managers may also be personally liable for breaches of such legislation by their

companies.

The Law of Workplace Safety

Page 9 of 10

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Vox Latina The Pronunciation of Classical LatinDocument145 pagesVox Latina The Pronunciation of Classical Latinyanmaes100% (4)

- Boat DesignDocument8 pagesBoat DesignporkovanNo ratings yet

- ACCA P1 Governance, Risk, and Ethics - Revision QuestionsDocument2 pagesACCA P1 Governance, Risk, and Ethics - Revision QuestionsChan Tsu ChongNo ratings yet

- Cursos Link 2Document3 pagesCursos Link 2Diego Alves100% (7)

- Duet Embedded Memories and Logic Libraries For TSMC 28HP: HighlightsDocument5 pagesDuet Embedded Memories and Logic Libraries For TSMC 28HP: HighlightsmanojkumarNo ratings yet

- Importance of Geometric DesignDocument10 pagesImportance of Geometric DesignSarfaraz AhmedNo ratings yet

- List of OperationsDocument3 pagesList of OperationsGibs_9122100% (3)

- The Meaning of Solar CookerDocument4 pagesThe Meaning of Solar CookerJaridah Mat YakobNo ratings yet

- Remembering Manoj ShuklaDocument2 pagesRemembering Manoj ShuklamadhukarshuklaNo ratings yet

- Rozgar Sutra EnglishDocument105 pagesRozgar Sutra EnglishRisingsun PradhanNo ratings yet

- Active Sound Gateway - Installation - EngDocument9 pagesActive Sound Gateway - Installation - EngDanut TrifNo ratings yet

- CSIR AnalysisDocument1 pageCSIR Analysisசெபா செல்வாNo ratings yet

- Anna University CTDocument3 pagesAnna University CTprayog8No ratings yet

- aCTION PLAN IN HEALTHDocument13 pagesaCTION PLAN IN HEALTHCATHERINE FAJARDONo ratings yet

- Eladio Dieste's Free-Standing Barrel VaultsDocument18 pagesEladio Dieste's Free-Standing Barrel Vaultssoniamoise100% (1)

- Polygon shapes solve complex mechanical problemsDocument6 pagesPolygon shapes solve complex mechanical problemskristoffer_mosshedenNo ratings yet

- Calculate Capacity of Room Air Conditioner: Room Detail Unit Electrical Appliances in The RoomDocument2 pagesCalculate Capacity of Room Air Conditioner: Room Detail Unit Electrical Appliances in The Roomzmei23No ratings yet

- AP Biology Isopod LabDocument5 pagesAP Biology Isopod LabAhyyaNo ratings yet

- Key Personnel'S Affidavit of Commitment To Work On The ContractDocument14 pagesKey Personnel'S Affidavit of Commitment To Work On The ContractMica BisaresNo ratings yet

- Big Data, Consumer Analytics, and The Transformation of MarketingDocument17 pagesBig Data, Consumer Analytics, and The Transformation of MarketingPeyush NeneNo ratings yet

- Vestax VCI-380 Midi Mapping v3.4Document23 pagesVestax VCI-380 Midi Mapping v3.4Matthieu TabNo ratings yet

- COP Grease BrochureDocument4 pagesCOP Grease Brochured86299878No ratings yet

- jk2 JAVADocument57 pagesjk2 JAVAAndi FadhillahNo ratings yet

- Hics 203-Organization Assignment ListDocument2 pagesHics 203-Organization Assignment ListslusafNo ratings yet

- Admission Notice 2023-24Document2 pagesAdmission Notice 2023-24Galav PareekNo ratings yet

- Chiller Carrier - 30gn-9siDocument28 pagesChiller Carrier - 30gn-9siZJ Limited (ZJLimited)No ratings yet

- UMC Florida Annual Conference Filed ComplaintDocument36 pagesUMC Florida Annual Conference Filed ComplaintCasey Feindt100% (1)

- Determination of Salicylic Acid'S Level in Acne Cream Which Sold in Kemiling Using Spektrofotmetry Uv VisDocument7 pagesDetermination of Salicylic Acid'S Level in Acne Cream Which Sold in Kemiling Using Spektrofotmetry Uv VisJuan LambeyNo ratings yet

- Coca Cola Live-ProjectDocument20 pagesCoca Cola Live-ProjectKanchan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Blink CodesDocument3 pagesBlink CodesNightin VargheseNo ratings yet