Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Taylor & Francis, Ltd. and Association of American Geographers Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Annals of The Association of American Geographers

Uploaded by

Svan HlačaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Taylor & Francis, Ltd. and Association of American Geographers Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Annals of The Association of American Geographers

Uploaded by

Svan HlačaCopyright:

Available Formats

Social Networks in Time and Space: Homeless Women in Skid Row, Los Angeles

Author(s): Stacy Rowe and Jennifer Wolch

Source: Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 80, No. 2 (Jun., 1990), pp. 184204

Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. on behalf of the Association of American Geographers

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2563511

Accessed: 24-11-2015 14:49 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Taylor & Francis, Ltd. and Association of American Geographers are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Annals of the Association of American Geographers.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Social Networksin Timeand Space:

HomelessWomen in Skid Row, Los Angeles

Stacy Rowe* and JenniferWolch**

of Anthropology,

*Department

of SouthernCalifornia,

University

Los Angeles,CA 90089-0042

**Schoolof Urban& RegionalPlanning,

University

of SouthernCalifornia,

Los Angeles,CA 90089-0042

Abstract. Social networksoperate withina

specifictime-spacefabric.Thispaper develops a theoreticalframework

forunderstanding the role of social networksamong the

homeless.The conceptoftime-spacedisconis offeredas a wayto conceptualizethe

tinuity

impactsof homelessnesson social network

formation,daily paths, life paths, personal

identityand self-esteem.Ethnographicresearchamonghomelesswomenin Skid Row,

LosAngelesis used to illustrate

thetheoretical

framework.Results indicate that homeless

womendevelop bothpeer and "homed" social networksas a meansof copingwiththeir

circumstancesand reestablishing

time-space

continuity.Networkrelationshipscan also

serveas substitutes

forplace-basedstationsin

the daily path such as home and work. The

characteristics

of social networksand daily

time-spacepathsappear to have affectedthe

identitiesand self-esteemof the homeless

women.

KeyWords: Homelessness,

socialnetworks,

daily/

lifepaths,

time-space

discontinuity,

peernetworks,

homednetworks,

homeless

ethnography,

women,

SkidRow.

OMELESSNESSin Americais widely

acknowledgedto be a nationaldisgrace,one thatwillnot go away.The

risingnumbersof homelessmen,womenand

childrenhavepromptedsocialscientists

to investigatethe dimensionsof the problem,the

complex natureof its causality,and its geographicdimensions(Baxterand Hopper 1982;

Lamb1984;Bassuk1984;Robertsonet al. 1985;

Erickson

andWilhelm1986;Bingham

etal. 1987;

Dear and Wolch 1987; Morrow-Jones

and van

Vliet1989).Thisbodyofresearchsuggeststhat

theremaybe up to 3 millionhomelesspersons

inthecountry,

concentratedin largecitiesbut

also scatteredthroughoutsmallertownsand

ruralareas.Manyoftheseindividuals

suffer

from

mentaldisorders,physicalhandicaps,and substance abuse problemswhichcontributedto

the onsetof homelessness.

Inaddition,economiccircumstances

haveled

to the growingnumbersof homeless(Robertson et al. 1985).Formost,homelessnessis the

end stagein a processof increasingmarginalizationdrivenby largerstructural

forces,includingdeindustrialization,

plantclosings,and

the rise of low-wageservicejobs; deinstitutionalization

and a restructuring

of the Americanwelfarestate;sociodemographic

shiftsresultingin greaternumbersof female-headed

households;and in manycities,skyrocketing

homepricesand rents(Bluestoneand Harrison

1982;Baer1986;Wolchet al. 1988).Thispolitical-economic context has increased the

chances thateconomicallymarginaland dependentpeople willfacejob loss,eviction,domesticviolence, loss of welfarebenefits,or

failureto gain access to appropriatecommunity-based

supportservices.

Despite a significant

researcheffort,

there

are serious deficienciesin our geographic

knowledge and understandingof homeless

people. Forexample,littleanalysisofhomeless

socialnetworks

or theirspatialcontexthasbeen

forthcoming

(forexceptions,

see Mitchell1987;

Glasser1988; Cohen and Sokolovsky1989).It

is well-recognized

thatnormalsocialnetworks

constitute

a sourceofsecurity,

health,andwellbeing(Cohenand Sokolovsky

1989;Sarasonand

Sarason1985; Whittaker

and Gabarino1983).

Theyalso providea wide rangeof materialresources (fromfriends,relatives,employers)

whichcan sustainmostpeople facingadverse

ofAmericanGeographers,

Annalsof theAssociation

80(2),1990,pp. 184-204

a Copyright1990 by Associationof AmericanGeographers

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Homeless Women in Los Angeles

circumstances

(e.g.,job loss,eviction,violence,

or loss of welfaresupport;Sinclairet al. 1984;

have found that

Wenger 1984). Investigators

the deterioration

of supportivenetworks,

due

to the combinedand prolongedpressuresof

poverty

and personalproblems,

can contribute

to homelessness(McChesney1986).

How do homelessindividuals

cope withthis

socialnetworks

breakdownin theirtraditional

intheirdailylivesitentails?

and thedisruption

How do theyrebuildtheirsocial networksto

obtainnecessarysupportinthe newsocialand

Howdo

contextofhomelessness?

geographical

these new networksand livingplaces affect

To date,most

personalidentity

andself-esteem?

homelessnessresearchhas focusedon quantitativeindicatorsand cross-sectional

analysis,

ratherthan the fine-grained,

qualitativeevidence about the dailylifeexperiencesof the

homelessnecessaryto answerthesequestions

(Koegel 1990).Thus,neitherthewaysinwhich

homelesspeople seekto reconstitute

socialties

(and thusgain access to associatedemotional

and materialresources),nor the geographical

have

dimensionsor contextof such networks,

receivedmuchscrutiny.

Inthispaper,we beginto addressthisgap in

the homelessnessliterature.Specifically,

we

for underpropose a conceptualframework

standinghomelesssocialnetworksin timeand

space,usingethnographic

analysesofhomeless

women in Los Angeles'sSkid Row area to illustrateour model.First,we providean overviewof the geographyof serviceresourcesin

our studyarea,SkidRow,and detailour field

methods.We thenpresenta model of homelesssocialnetworks,

fromthe

usingillustrations

research.Thismodelemphasizes

ethnographic

the role of social networksin meetingbasic

needs and delineatesthe waysin whichtime

and space shape the socialnetworksof homeless individuals.

Italso stressesthatforthe average"homed" or stablydomiciledindividual,

social networksand dailypathscreatea powwhichin

erfulsense of time-spacecontinuity,

turnmoldsindividual

and self-esteem.

identity

Homelessness,in contrast,createstime-space

discontinuity-thelack of locationally-fixed

stationsin the dailypath.Our examplesshow

howtime-spacediscontinuity,

and thestruggle

of homelesswomen to survivein a degraded

can alterperand threatening

environment,

sonalidentity

and haveimpacton self-esteem.

The examples also illustratehow homeless

185

womenrebuildtheirsocialnetworks

and in so

doing,tryto reestablish

time-spacecontinuity

and a valuedindividualidentity,

bothofwhich

areessentialincopingwithand recovering

from

homelessness.

Our conceptualmodeland findings

basedon

ethnographic

researchprovideotherscholars

withtestablehypotheses

aboutsocialnetworks

of homelesspeople. Theymayalso assistthe

helpingprofessions

understand

howsocialnetworkscan be rebuiltand how theymightfacilitatethe re-entryof homelesspeople into

the mainstream

of Americansociety.

Investigating

Social Networks

among the UrbanHomeless

Our ethnographicresearch on homeless

womenwascarriedout overa two-yearperiod

in the Skid Row area of Los Angeles.First,in

orderto providea geographical

contextforour

findings,

we briefly

characterizethe structure

ofthe SkidRow district

and describeitsspatial

organizationand resources.Next,we outline

the ethnographicmethodsemployedin the

field.

GeographicalContext:SkidRow,LosAngeles

SkidRowisa dingy,

arealocated

deteriorated

intheclassiczone oftransition

eastoftheCentral BusinessDistrict.The historicallocus of

transient

workerhousingin Los Angeles,Skid

of resRow's housingstockconsistsprimarily

identialhotels,roominghouses,and low-rent

The 1970s markedthe beginning

apartments.

ofa majorincreaseinthe numberand typesof

privatesocialserviceagenciesand shelterprovidersinthearea.Thisincrease,whichcontininthe

a shift

ued throughout

the 1980s,reflects

numberand needs of the residentsofthe district.Estimates

ofthecurrent

populationofSkid

Row fluctuatefrom6000 to 30,000.The populationforthetwocensustractswhichaccount

formostof the districtwas placed at 8979 in

1980.Thereis a consensusthatthe population

has continuedto growand changeat a rapid

pace (Hamiltonet al. 1987).Priorto 1980,the

ofolderwhite

populationwascomprisedmainly

men, manyof whom were alcoholicsor disabled,andwho livedon publicassistance.Now,

however,the populationis generallyyounger

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rowe and Wolch

186

10

,\

DPSS WelfareOffice-

-~8

--\

, ,

0~~~

~.Love Camp~

I0

I

FredJordanMission

ii /t'

*^

S~~~~~~f5;;

f ..az

r

L 'U'

B X...vg~~~~~~~~~~~~~cj3,x&

LawCenter

InnerCity

0*~~~~..

..

.fii?28

San JulianPark

0~

*...CityHall.

-,a,

,B'

GrandCentralMarket

Perfacp

','.B

.... . ...

...

ssBB

Clifton'sCafeteria

*-*-Justiceville

c'

$

*

*--

Overnight shelter facilities: men only

Overnight shelter facilities: women only or men and women

Hotels

Social service providers

no shelter facilities

Park

Park

I

Skid row boundary

_____.

Feet

~~~~~~~0

~

1000

?I

ofservicesin SkidRow,Los Angeles.

Figure1. Distribution

and morediverse.It includesmanyblacksand

Hispanics,

singlewomen,andfamilies

withchildren (Robertsonet al. 1985; Hamiltonet al.

1987).

The growthof shelterand serviceresources

hastransformed

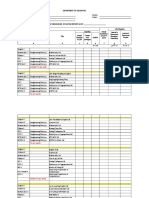

SkidRowintothelargest"service hub" in the city(Fig. 1). Some of these

resourcesare outsidetheofficial

boundariesof

the neighborhood,

as definedbythe City,but

are heavilyused by Skid Row residents.Currently,there are approximately

2000 shelter

beds in SkidRow. Halfthatnumberare available to womenand justover 100 beds are exclusivelyforwomen. Longer-term

housingis

availablein the area's SRO (SingleRoom Occupancy)hotels(countingthehotelsone block

beyondofficial

SkidRow boundaries,approximately6700 units;Hamiltonet al. 1987).Some

of these hotels accept short-termhousing

vouchersfromthewelfaredepartment

and are

thussimilarto emergencysheltersinfunction.

In additionto the shelterfacilities,

thereis a

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Homeless Women in Los Angeles

publicwelfareoffice,and more than50 programsare providedout of the social service

agencies, missionsand shelters.These programsinclude meals,clothing,advocacyand

legalassistance,alcoholand substancedetoxificationand counseling,health and mental

healthcare, familyassistance,outreach,employmentplacementand special servicesfor

NativeAmericans.

Two vestpocketparks,managed bytheSingleRoomOccupancyHousing,

Inc. (an SRO rehabilitation

agency) provide

greenspaceforsocializing

andrecreational

uses.

Charitablegroupsfromoutsidethe area (parcome intoSkidRow

ticularly

churches)

regularly

to serve mealsto homelessand otherneedy

SkidRowresidents;San Julian

Parkand Towne

Avenueare the commonsites.

The risein the numberof socialserviceand

shelterproviders

sincethe 1970shasbenefited

theresidentsoftheareaand hasdrawnhomelesspeople fromservice-poorpartsofthe city

(e.g., South CentralLos Angeles).The expansionof resources,however,has notkeptpace

withthe rapidlyincreasingneed forservices.

Compoundingthis is the factthatsince the

1970s,therehas been almostno new housing

constructionin Skid Row, only demolitions

whichhavereducedthesupplyofSRO housing

(by more than2000 unitsbetween 1969 and

1986; Hamiltonet al. 1987).As a result,an estimated500to 4000SkidRowresidentsmaybe

withoutshelteron anygivennightand thouand/ormarginsandsofothersaretemporarily

allyhoused(Hamiltonet al. 1987).Those without shelteroftensleep on thepublicsidewalks

or in nearbyparksor vaadjacentto missions,

cantlotsand buildings.

Ethnographic

Analysis

The datacollectedand analyzedforthisparesearchconper are based on ethnographic

ductedinand aroundSkidRow.The studyentailedtwo phases. The firstphase involveda

intwo

lengthy

periodofparticipant-observation

inorneartheSkid

homelessstreetcommunities

Thiswasfollowedbya smallnumRowdistrict.

interberofformaland lengthy

keyinformant

of whichwere conductedwith

views,the first

homelesswomen who participatedin these

or who livedin a nearbyshelter.

communities

The participant-observation

phase began in

1986.Initialcontactwiththe homeless

January

187

a streetcommuwas limitedto "Justiceville,"

The group

organization.

nitywitha semiformal

corporationunderthe name

was a non-profit

Home forthe Homelessand exhibiteda hierarchical structure.Ted Hayes, a grassroots

was the

homelessactivistand formerminister,

recognizedleader of the group,and a core

These indigroupfunctionedas hisassistants.

vidualsexercised limitedauthorityover the

populationthatcomprisedthe refluctuating

mainderof the community.No formalfield

notes were recordedduringthisperiod,nor

conducted.Presencein

wereformalinterviews

wassporadicbuton-goingand

thecommunity

and

includedcasualconversations

participation

and

the occasionalprovisionof transportation

food. Documentation of the community

was initiatedin Janthroughstillphotography

uary1987 and continuedthroughoutthe research.

particlocationof the informal

The primary

ipant-observationand photographicdocushiftedinSpringof 1987to theLove

mentation

Camp on FourthStreetand Towne Avenuein

downtown Los Angeles. The Love Camp,

hada more

anotherinformal

streetcommunity,

stablepopulationand locationthanjusticeville,

as mostofthe membershad tentsor dwellings

constructedof wooden palettes and cardofthe

structure

board.Alsotheorganizational

Love Camp was less rigidthanthatof justicewasinformally

sharedbyDavid

ville.Leadership

Bryantand Adam Binion,but not all camp

nor was

membersrecognizedtheirauthority,

thisa criterionforresidency.Casual converand

sationwithcamp members,photography

the provision of transportationand small

amountsof cash continueduntilthe dispersal

of the camp.

Inthewakeofmounting

pressurebythelocal

LoveCampwas

SkidRowbusinesscommunity,

in

dispersedbyCityof Los Angelesauthorities

June1987,coincidentwiththe openingof a

fencedoutdoorcampgroundforthehomeless

on the banksof the Los AngelesRiver.Many

LoveCampresidentsenteredthecampground

The outdoor

as did membersof Justiceville.

campgrounditselfwas closed withina few

months,dispersinghomelesspeople to other

pathswere not

partsofthecity.The migration

documentedformembersofeithergroup;

fully

membersstayedtogetherand

someJusticeville

moved to Venice Beach untiltheywere once

againdispersedbyCityauthorities.

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

188

Rowe and Wolch

A transitional

residencefor homelessand

batteredwomen and their familiesin the

downtownarea was a thirdsiteof participantobservation

and photographic

documentation.

Participation

as a volunteerandfounding

member of the sponsoringorganizationincluded

directinvolvementin the day-to-dayoperationsof the shelter,talkingwiththe women,

playingwiththeirchildren,and providing

services such as transportation,

advice, encouragement,and crisisintervention.

Formal,taperecorded interviewswere conducted at this

shelterinthefallof1987.Two otherinterviews

withwomenwhowereformer

membersofJusticevillewere conducted in the same fall.All

interviews

conductedin 1987 focusedon the

women's experienceswith the Los Angeles

CountyDepartmentof Publicand Social Services (DPSS),but a wide rangeof topicsconnected withSkid Row survivalstrategiesand

socialtieswas also discussed.

Clifton's

a popularrestaurant

inthe

Cafeteria,

downtownarea frequentedby the homeless

was chosen as a site forfurther

community,

in January

participant-observation

1988. Contactwas also reestablished

withformermembers of Justiceville

and the Love Camp. Two

womenwho had livedin the Love Campwere

located and interviewedin thisphase of the

research.Theseinterviews

werebroadinscope

and the topicsof discussionwere initiatedby

the women,as well as by the researcher.In

addition,formalobservations

were made at a

newencampment

at Firstand Broadway

streets

in downtownLos Angeles.Fieldnotesregardingtheseobservations

and the contextsofthe

interviews

were recordedand manystillphotographsdocumentedthe siteand residents.

In accordance withstandardethnographic

methods(Wernerand Schoepfle1987;Spradley1979),carefulattentionwas devotedto acthe taped interviewsin

curatelytranscribing

orderto preservethe grammar,

and

structure,

flowoftheconversation

as itwas convertedto

writtenlanguagewithpunctuation.However,

the lengthof a pause,

subtletyof inflection,

facialexpression,and body gestures

laughter,

(whichoftencommunicatemeaning)have not

been captured.Since quotationsare removed

fromthe contextof the conversation,

these

are subject to

excerptsfromthe transcripts

some degree of misinterpretation

(both by

readerand authors).All interviews

were conductedwiththe expressknowledgeand con-

sent of the women,but all nameshave been

such

changedexceptforthoseofpublicfigures,

as therecognizedleadersofthevarioushomeless communities.Also permissionwas obtained for all photographyand in most instancesthesubjectsreceiveda copyoftheprint.

of prints

and the distribution

Photography,

commuto membersof the variousinformal

nities,was an integralpartof the process of

the researchpethroughout

rapport-building

riod (Fig.2).1 It provideda role in the comwho was oftenremunity

forthe investigator,

ferred to and introduced as "the camp

Alsotheprocessoftakingphophotographer."

tographs,and photographyin general,often

with

providedan initialtopic of conversation

unfamiliarindividuals. When prints were

a

broughtback to Skid Row and distributed,

was estaboftrustand reciprocity

relationship

werealso used ininformal,

lished.Photographs

documentedin the fielduntapedinterviews

notes,whichaided in the data analysis.(See

Collierand Collier1986,and Wagner1979for

expanded discussionsof the role of stillphoinsocialscienceresearch).Thusphotography

and the longdurationof timespent

tography,

becomingacquaintedwiththe homelessindiallowedfora depth

vidualsand theirlifestyle,

of mutualrevelationand understanding

bethat

tween field researcherand informants

to achieve through

would have been difficult

othermeans.

Homeless Social Networksin

Time and Space: a

Conceptual Model

involvea

social interactions

Anyindividual's

finiteset of people, definedas theirsocialnetwork.Simplystated,social networksare comwhomone knows,

posed of those individuals

and fromwhom one obtainsmaterial,emotionaland/orlogistical

e.g.,kin,friends,

support,

and serviceprovidworkassociates,neighbors,

ers (Bott1957; Mitchell1969;Fischer1982).A

socialnetworkcan also be regardedas a time(Willspace mapofrepeatedsocialinteractions

mott1986;Fischeret al. 1977).These repeated

occur in the courseofan individinteractions

ual's dailypaththroughtimeand space,which

both shapes and is shaped by the social netof individuals,

the pivwork.Forthe majority

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

189

Homeless Women in Los Angeles

cam

_X~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

_w

2.Hmls

_ir

I~~N

omnnxohr lwo oe

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

190

Rowe and Wolch

otal stationsin a dailypathare the home and

workplace-pointsofconstantreturn,

essential

functions(eating,sleeping,personalprotecand intion,storinggoods,communications),

tensesocialinteraction.

Together,the dailypathand socialnetwork

constitutean individual'slocale. The locale

containsboththephysical

space definedbythe

dailypathand itssocialcontext.Itthusincludes

environmental

social institutions

and

features,

individualspresentin the space. Locales are

symbolicof individualexperiencesand aspirations(Tuan 1977),and serveas the "focusof

meaningsor intention,

eitherculturally

or individuallydefined"(Relph 1976, 55). Psychologicalattachments

to thelocaleare significant

intheconstruction

ofpersonalidentity

(Searles

1960;Godkin1980).Further,

controlofthe locale indexes one's social statusand relative

powerwithinthecommunity

(Dearand Wolch

1989).The qualitative

aspectsoflocalesalso influenceindividualself-esteem(Godkin1980).

Thus,iflocalesoccupied duringthe courseof

the daily path (e.g., the home, workplace,

school) are perceivedas fallingbeneath culnormsacceptedbytheindividturally-derived

can drop.The relativehoual,thenself-esteem

mogeneityof the locale,or the perceptionof

samenessamongproximate

individuals,

can also

affectindividualself-esteemand social networks(Smith1981).

Over time,dailypathsaccumulateto form

lifepath.Dailypathsand lifepaths

an individual's

interact,

eachforming

andreforming

theother.

Thisdaily/life

pathdialecticprovidesa cumulativeexperientialbasisforidentity

and influences self-esteem

(Pred1985).Thisimpliesthat

time-space

continuity,

or the degree to which

successivedailypaths resembleone another

and occur in the same locale,shapespersonal

The

identityand its subjectiveconnotation.2

the

longerthedurationofsimilar

dailyroutines,

exertedbythoseroutines

greatertheauthority

in the definition

of self.

canbe characterized

as thelack

Homelessness

of time-spacecontinuity

or simplytime-space

has imdiscontinuity.

Time-spacediscontinuity

forthe developmentof

portantramifications

socialnetworks

intimeand space. Inparticular,

theabsenceofa homebase restricts

thehomeless individual'saccess to familyand friends,

and vice versa.The workplace,anothersource

of social contacts,mayno longerbe relevant.

Thisbreakdownof traditional

social networks

pathsleads homeless

and changesin daily/life

people to develop waysto acquire resources

whichdo notdependon eithera spatially-fixed

meansof

home base or a job site.Alternative

supportincludepublicand privatesocialwelpanhandling,collectingrefare institutions,

cyclable materials,day labor and illegalactivities (e.g., drug dealing, thievery and

Inlightofthis,thesocialnetworks

prostitution).

differ

formedwithinthe homelesscommunity

in both compositionand spatialorganization

fromthose formedwithinthe homed community.

as

We characterizehomelesssocialnetworks

havingtwo basic components:peer networks

and homed networks(Fig.3). Peer networks

homeless

includehomelessfriendsand family,

homelesscommuniinformal

lovers/spouses,

(liketheLove

tiesbased instreetencampments

Camp),and membersof homelesspoliticalorHomed netganizations(such as Justiceville).

worksreferto socialtiesbetweenthehomeless

individualand membersof the homed community.These latterincluderemnantsof the

homeless individual'sprior social network;

in

"clients"or donors;workmates

panhandling

casual labor;social workersand otherservice

homedre(and,fora smallminority,

providers

searchersand advocates).The compositionof

as wellas the

bothpeer and homednetworks,

occur,can be

places wheresocialinteractions

unstableand fluctuateover time,given the

ofthe homelesspopulation.Nevertransiency

theless,forhomelesspeople, thesesocialnetwhichcan occurat variable

workrelationships,

pointsin urbanspace,appearto replacetherole

in thedailypathin

stations

of locationally-fixed

maandproviding

continuity

time-space

creating

support.

and logistical

emotional

terial,

The hardshipsand time-spacediscontinuity

associatedwithhomelessness,and the devalued locales whichmosthomelesspeople are

the

forcedto occupy(e.g.,SkidRow),influence

pathdialectic.Notsurprisingly,

dailypath/life

and dailyroutinesof homeless

socialnetworks

people are used to meettheirimmediatesurlifegoalsare

vivalneeds.Asa result,long-range

Skid

of necessityrelegatedto a low priority.

rich

whileoftenrelatively

Row environments,

in formalservices,maybe perceivedas unsatin comparisonwithpriorresidential

isfactory

settingsand carrythe stigmaassociatedwith

and last resort.

places of social marginality

physMoreover,SkidRow zones are typically

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Homeless Women in Los Angeles

PEER NETWORK

HOMED NETWORK

Spouse /Lover/Family

HomelessFriends

ofInformal

Members

HomelessCommunity

191

ofFormerNetwork

Remnants

OMELE

Clients

Panhandling

INDIVIDUAL

Members

ofPolitical

Organizations

Social Workers

FormalServiceProviders

Researchers

/Advocates

Figure3. Homelesssocialnetworks.

icallydegraded,and expose the newlyhomelessto an aliensocialcontextof extremepoverty,crimeand substanceabuse.Often,a result

is loweredself-esteem,

and a shiftin personal

identity.Thepreeminence

of short-term

needs

and a devaluedlocalecan lead to an alteredassessment

of lifeplansand priorities,

and a transformed

senseofself.

In thiscontext,supportivehomelesssocial

networks

areparticularly

vitalto therestoration

of a positiveand valued personalidentity.In

thesectionsthatfollow,we drawon resultsof

theethnographic

to illustrate

analysis

ourconceptualmodelofhomelesssocialnetworks

and

its implications.We concentrateon lover/

and streetencampments,

spouse relationships

as these typesof peer linkagesappear to be

centralto the homelesswomenin our sample.

Sinceremaining

tiesto thepriortraditional

socialnetworkare minimal

forthesewomen,and

linksto researchers/advocates

relativelyunusual and/or sporadic, our examinationof

homed networksfocuseson the role of panhandlingclientsand formalserviceproviders.

Home Is WheretheHomelessAre:

Peer Networks

Homeless people share theirlocales with

otherhomelessindividuals,

theforfacilitating

mationof peer networkswithinthe homeless

population.Peer networksare comprisedof

homelessacquaintances,

friends,

family,

lovers,

and spouses; some peers will live in informal

streetcommunitiesor encampmentsof the

homelesswhichoftenariseinvacantlots,parks

and sidewalksinSkidRow. In manywaysthese

peer networksreplace the functionof the

home-basein the maintenanceof time-space

continuity,identityand self-esteemfor the

generalhomelesspopulation.The formation,

utilizationand importanceof peer networks

appear to varybetween homelessmen and

women.

Lover/SpouseRelationships

Womenseem to be muchmore likelythan

mento enterintoa lover/spouserelationship.

Thisdifference

maysimplyreflectthe demoof

graphiccompositionof the area. Estimates

the femalepopulationresidingin Skid Row

rangefrom6.5(McChesney1987)to 23 percent

(Robertsonet al. 1985).Eventhemostgenerous

estimateofthefemalepopulationindicatesthat

malesfaroutnumberfemales.Thus,even men

who wish to enter into a lover/spouserelasmall

tionshipare constrainedby a relatively

pool of availablefemalepeers.

Butthegenderimbalanceindemography

also

pointsto anotherfactorwhichmaymotivate

women to seek a lover/spouserelationship:

vulnerability

to physicalattack.Many homed

vulindividualsalso reportfeelingphysically

nerableintheircommunities;

however,homelesswomenmaybe atan increasedriskofattack

because of theirresidencein SkidRow. Many

womenmustsleep on thestreetiftheydo not

have the moneyfora hotel,since the shelter

resourcesforwomenin the SkidRowarea are

inadequate.As a result,homelesswomenmay

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rowe and Woich

192

kit~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

K~~~~Fgr

oees

withmento satisfy

imenterintorelationships

mediateneeds forprotection.In thisway,the

lover/spouse relationshipfunctionsin the

mannerof a home-base.

The locationof one's partnerservesadditionalhome-basefunctions.For example,the

lover/spouseis a personto whombelongings

and messagescan be entrusted.The relationship allows fora pooling of resourcesand a

"domestic"divisionof labor(Fig.4). Also sigthe lover/spouse,

to whomone renificantly,

turnseach day,createssome degree of timein the dailypath.In effect,a

space continuity

ratherthan

personbecomesthepointofreturn,

the place.

Rita and Paul provide an example of the

home-basefunctionsof the lover/spouserelationship.One memberof the couple would

staywithall theirbelongings,at or near the

currentsleepingarea. The partnerwouldthus

be freeto leaveandsecureresourcesnecessary

forsurvival.

Forexample,Paulwouldoftenstay

in the parkat Firstand Broadway,where the

couple had spentthe night,whileRitasought

opepeaigdne

j4

legal aid, panhandledfor money and then

boughtfood for the couple's eveningmeal.

Whileshe was gone,access to herpossessions

was controlledbyPaul,and messagescould be

leftforherthroughhim.Paul'slocationinthe

park(orotherresting

spot)wasthepivotalpoint

forRita'sdailypath;itwaswhereherdaybegan

and ended (Fig.5).

are based

Many lover/spouserelationships

These

on mutualaffection

and companionship.

relationships

can be a sourceofemotionalsupand positiveself-esteem.

The export,identity

tent of positiveself-esteemaffordedto the

homelesswoman maydepend on the nature

of her relationship

and the partner'sstanding

in the homelesscommunity.

The durationof

the relationship

influencesthe woman'sselfdefinitionas a partner.This identitycan be

reinforcedby communityrecognitionof a

woman'sstatusas a particularman's loveror

spouse. Such recognitioncan affordher protectionfromharassment

even when her partner is not physically

present.

fromPam'sinterview

how

Excerpts

illustrate

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Homeless Women in Los Angeles

24

ffi

Parkat Broadway

& FirstStreets

22

20

A

I

(dinner,

_l sleep)

Paul

-

(Safeguarding4fi

GrandCentralMarket

(Shop forfood)

couple's i

posessions)

16

18

193

14

<

12

Rita'sPanhandling

Spot

(City Hall)

10

08

06

InnerCityLaw Center

(Legal aid counseling)

04

02

00PAUL

Parkat Broadway

<

RITA

& FirstStreets

Space-

(a)

Time

Space Prism

ALAMEDAST.

CD)

Inner City

Law Center

~~~~~2

CityHall

PanhandlingSpot 3

Park at Broadway 1, 5

& First

W

W

MAINST.

Grand Central Market

(b) SketchMap of Rita's Stationsand Path in Skid Row Area

Figure 5.

A typicaldaily path for Rita and Paul.

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

194

Rowe and Wolch

herrelationship

withherhusbandTeachplayed

a positiverole in her life.Upon theirarrivalin

the couple's car was impounded.

California,

Withoutresourcesto recoverthevehicleor to

obtainsleepingquarters,the twowere forced

to walk the streetsof Santa Monica forfour

daysbeforetheyfoundshelter.Pam was four

monthspregnantat the time.Teach provided

Pamwithvitalencouragement,

nutrition,

companionshipand emotionalsupport. He also

represented

thecouple ininteractions

withauthority

figures.

Pam:We didn'thaveno way,we didn'thavenothin'to eat and thereain'tno missions

or nothin'out

therein SantaMonicaat all.... [H]e was tryin'to

make a game of it, you know.And, you know,

singing

and"A littlebitfurther."

andlaughin'

Jokin'

and stuff.

And I knewhe wastiredbutI thoughtI

was gonna just drop over,I was exhausted.And

whenwe gotinthehotelon NewYear'sEveI slept

throughit. I sleptfortwo days,you know.He'd

wakeme up and ask me,and giveme a drinkand

askme did I wantsomethin'to eat and I'd sayno.

You know,and he'd makeme ... I rememberbananas,that'swhathe wasfeedingme,becausethey

was easy,you know,to get down.

Pam'sroleas Teach'swifeand themotherof

theirchildprovidedherwitha positivesense

Theirrelationship

of identity

and self-esteem.

(likethatof Paul and Rita)was based on reciprocityand mutualsupport.However,many

homelesswomen (like theirhomed counterparts)are involvedin lover/spouserelationTheir

shipswhichareabusiveand/orexploitive.

social

threatening

locale,absenceoftraditional

and vulnerability

to physicalattack

networks,

oftenleadthemto toleratethenegativeaspects

A relationship

of lover/spouserelationships.

maystillservethe logisticaland materialfunctionsofthehome-base,buttheeffecton idenWith

tityand self-esteemcan be devastating.

no alternativehome-base,homelesswomen

oftenen(again,liketheirhomedcounterparts)

dure predictablepatternsof abuse fromtheir

danpartnerratherthanfacetheunpredictable

gersof the streetsalone.

WhentheLoveCampwasdispersed,Lisaand

herlover,Matt,movedintoa SkidRow hotel.

MattstayedintheroomwhileLisapanhandled

to meetthe couple's dailyneeds. Lisawas amwithMatt.She

bivalentabout herrelationship

abusiveandthat

admittedthathe wasphysically

he exploitedher,butshe continuedto remain

withhim.

twopeople on tendollars

Lisa:Me, I'msupporting

a day.The otherdayI gothomeand he waspissed

offbecauseI onlyhad$12.... WhenI come home,

I'llputmoney

I'lltakemychangeI have,sometimes

init.Wrapitup and putitinmylittlehidingplace.

He has yet to findit.... You see all these little

dollar

blackand blues?Becausehe wantsa fucking

and a quarter?I said,"Nope, sorry."But I don't

havethe moneyto move.

AlthoughMattinsultedherand undermined

Lisaseemed to preferthissitherself-esteem,

uationto the prospectof facinglifeon the

streetsalone. She did assertherindependence

from

byhidingmoneyand cigarettes

covertly,

Matt,butthe priceshe paid forthiswas often

physicalabuse.

InformalStreetEncampments

streetencampin an informal

Participation

forhomementcanalsoserveas a replacement

base and hence recreatestime-spacecontinuityforhomelesswomen(as wellas forsingle

men and couples). In SkidRow such informal

oftenbecomecooperativegroups

communities

whichorganizeto providesecurityforcommunitymembersand theirpossessions(Fig.6).

as a contextforsoThe camp also functions

cial interaction.It is a place where messages

of concernto the

can be leftand information

and utiis shared.The formation

community

by

lizationofsocialnetworksis thusfacilitated

participationin the community.These netmateworksbecome the sourcesof logistical,

rialand emotionalsupportonce providedby

networkspriorto the homelesseptraditional

are oftennamed(e.g.,

isode. The communities

Love Camp) and manyresidents

Justiceville,

themselvesas members.A diproudlyidentify

typvisionoflaborand delegationofauthority

icallyoccurunderthedirectionoftheinformal

in the group'sdecision

leaders.Participation

projects,such

makingprocessand community

as cookingand cleaning,can heightenself-esas a productiveand

teemand promoteidentity

memberof camp life.

contributing

Because encampmentsare so highlyvisible,

autheyare oftendispersedbygovernmental

Membersofthedisruptedgroupfrethorities.

quentlymigrateto new sites en masse,thus

continuityin the social network

maintaining

Forrelatively

even thoughtheirlocationshifts.

thecamp

shortperiodsoftime(weeks,months),

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HomelessWomenin Los Angeles

195

V_

-SECURITY.

at LoveCamp.

Figure6. Securityoffice/residence

becomes a stablepointof returnin the daily

pathsof itsresidents.

herselfas one of the

Lisaproudlyidentified

originalmembersoftheLoveCamp.The camp

providedLisa withtime-spacecontinuityby

as a home-baseand allowingLisa

functioning

to expandher social network.Homed friends

becamefriends

offellowresidents

andrelatives

and resourcesto Lisa.Lisarecognizedthatthe

lifeare thosethathave

"veterans"oftransient

and dealwithtimeacceptedenforcedmobility

peer netby maintaining

space discontinuity

works.

Lisa:... Otis,Sue,Roger,allthesepeople thatlived

on our side of the streethad been thereforall

thosemonths.Theyhad been togetherforyears.

Theywere used to thisbeing moved fromone

placetoanother.Linda,whohadbeenon thestreet

forsevenyears,hey,thiswasnothingnewto them.

We'rejustgettingmovedagain.They'dgone from

one parkinglot to another.Thiswas nothing,to

sayhey,yougot to pack up and go.

are continuousand

Because thesenetworks

close knit,thereis a measureof controlover

outsideaccess to thegroup'slocale. Members

of the encampmentknow who "belongs" in

thearea.Thisprovidesprotectionand security

forcamp membersand theirpossessions.For

example,Lisastressedtheprotectionprovided

bythe encampment.Priorto her relationship

withMatt,she was marriedto anotherabusive

man. Duringher stayat the Love Camp, she

to leave him.The sourceof

foundthestrength

and support

thatstrengthwas the continuity

of her peer networkat the Love Camp, enand leave the

ablingherto asserther identity

abusiverelationship.

Lisa:... I justone daysaidthat'sit.That'sit,and I

and I movedup Towne Street.ButI

got mystuff

had 20 people to watchmyback over the guy.

Because he would have hurtme, but there's20

people thatdidn'tlike him,thatdidn'tlike him

because of whathe was doingto me. So I didn't

haveto worryabout it.

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

196

Rowe and Wolch

Althoughlackinga roofand fourwalls,resoftenallow

identsfeelthatstreetencampments

a morestablelifewithbetterqualitythanresidence in a SkidRow hotelor shelter;no resourcesmustbe divertedto payrent,and the

isnotconstrained

individual

byhotelor shelter

management

(whichoftenlimitsthe duration

ofresidence,imposescurfews,

and/orrestricts

As Ritaexplains:

visitors).

Rita:And that'swhypeople stayon the streets

because theirmoney.... At leasttheycan buy

I meanthissounds

shampoo,washinthewashroom,

crazybut itstrue.Theycan buy cigarettes,

they

can buyfood,certainthingsthattheyneed, personalproducts.... [Ina hotelor shelter][Y]ougot

a roombutnone ofyourneedsare metexceptfor

shelter.

in the informal

communiThus,participation

tiesmayactuallyincreaseindividual

choiceand

self-determination,

and provide excess resourceswhichcan be accumulatedforinvestmentin longer-term

projects.

As encampments

growin size and visibility,

theyoftenreceivedonationsfromchurchand

communityorganizations.Grillsfor cooking,

food,clothing,and personalgoods were distributedamongLove Camp members,forexample. A camp thuspromotesmaterialaccumulation,and servesas a source fordonated

utigoods. Thishelpsthe residentseffectively

lize theirlimitedstockof resources.Lisatells

how variousgroupsand individualsdonated

itemsto the Love Camp. She mournsthe loss

ofthesematerialgoods whichhad to be abandoned once the groupwas dispersed.

Lisa:Butwhatwasupsetting

wasthatso manypeople haddonatedso manythingsto us.Forinstance,

aid. We

withall the healthsupplies,first

Thrifty's

hadthegrillsthatpeople donated.Thosebeautiful

grillsthatthe churchpeople donated.The tents

thatthechurchpeople donated.FredJordan's

gave

me mine.

Homeless Interactionswiththe

Homed Community:

Homed Networks

withthe peer

Althoughsocial interactions

networkmaydominatethe socialnetworksof

homelesswomen, contactswith the homed

are also vital.In manyrespects,the

community

whichlead to socialtieswithhomed

activities

suchas panhandling

individuals,

and obtaining

formalwelfareservices,replacethoseformed

The locawithinthe contextof employment.

tionofinteractions

withthehomedcommunity

istypically

fixedintimeand space,allowingthe

somedegree

homelessindividual

to reestablish

inthedailypath.Also,

oftime-spacecontinuity

institutionalized

normsofbehavior(acceptable

rulesgoverning

panhandling

sites,bureaucratic

welfare-recipient

activities)tend to structure

theinteractions

betweenhomelesswomenand

theirhomednetworks.

Aswithpeer networks,

and

homed networkscan undermineidentity

self-esteem.They can also provide essential

material

andemotionalresourcesand reinforce

when the

particularly

time-spacecontinuity,

relationships

transcendtheirdefiningcharacwelfarerecipient/social

ter(panhandler/client,

worker).

Panhandling

Manyhomelesswomenrelyon panhandling

activities

to providetheresourcesnecessaryto

In

meet theirdailysubsistencerequirements.

thissense, panhandlingis analogousto a job.

Most panhandlershave a fixedsite, around

whichtheirdailypathsrevolve.Asa result,

many

occur withinthis

of theirsocial interactions

context. At times, homeless women form

friendlyrelationshipswith membersof the

whom theyregularly

enhomed community

counter. The social networksformedwith

through

membersof the homed community

panhandlingcan be sourcesof logistical,material and emotionalsupport,and serve as

sources of positiveself-esteemfor homeless

women.

Lisapanhandledin frontofClifton'sCafeteria,whichhas a largeelderlyclientele.Often

shewrotelettersorcleanedhouseforher"regulars,"even iftheycould not pay herforher

servicesatthetime.Thisreciprocalrelationship

herself

as a helpful,

allowedLisato identify

productiveperson.

Lisa:There'sa guythatcomesfromLomaLinda

manthatI methere

a 93-year-old

everySunday,

andhesays

onedayI askedhimforsomechange,

to his

"Canyouwrite?"....AndI wrotea letter

I didevery

daughter....Andthatgottobea thing

from

forhim.I gotlunchandfivedollars

Sunday

himforwriting

a fewletters....AndlastSunday

he wasrealupsetbecausehe'sbeenlowon cash.

He says,"I don'thaveanymoneyto giveyou."

I said.

that'sok,no problem,"

"Arthur,

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Homeless Women in Los Angeles

Women who panhandlemaybe perceived

as less threatening

by the homed community

thantheirmalecounterparts,

facilitating

social

interaction

and the formation

of friendly

relationships.

But women who panhandlemust

also faceabusivebehaviorfrompassersby.

The

mostdegrading

formofsuchabuse isthesexual

propositions

thewomenmustendureon a frequent basis.To preserveher self-esteem,

Lisa

had drawndefiniteboundariesin her interactionswithherpatrons.She distinguished

herselffromwomenwho are prostitutes,

inan effortto preserveheridentity

and self-esteem.

Lisa:I havepeoplethatsay,"Hey,I'llgiveyoutwentydollars

ifyoucomeuptomyroom.I gotmoney

movie

"Wanttogotoa dirty

upthere."Nothanks.

withme?""Youwanna,

youknow.""CanI touch

you?IfI cantouchyouI'llgiveyousomemoney."

No, no ... I'm nota hooker,I'mnota prostitute."

Manywomenare proud of theiridentity

as

a panhandlerbecause theydo nothaveto rely

for

solelyon public or charitableinstitutions

theirsupport.Panhandling

providesan undocumentedsource of incomethatsupplements

or replacesinstitutional

assistancewithoutafforwelfareprograms.When

fectingeligibility

and wherean individual

panhandlesisa matter

of personalchoice. An individualcan panhandle as long and as oftenas she chooses, dependingon immediateneeds. Thus,the daily

path of the individualis definedby personal

considerationsratherthan by the authority

constraints

imposedbyinstitutional

supportand

serviceproviders.Butat the same time,pansourceofincome,

handlingisan unpredictable

ofresourcesforlongtheaccumulation

making

terminvestment

difficult.

Lisa:Mypreference

isI'mgoingto go panhandle,

I'llmakemoremoneydoingthat.Andso fora

dollars.

coupleofdaysI madeforty

Ah,hey,I'm

dolgood.Then,allofa suddenitwentfrom

forty

Itwasboom,a

larsto almostten,twelvedollars.

realdrop.

constraints

do

Moreover,at timesauthority

interfere

witha woman'sabilityto panhandle.

Ritaworkedin frontof CityHall forseveral

monthsbeforeshe was threatenedwitharrest

ifshe returned.In the absence of a suitable

siteand the loss of associatedinpanhandling

come and socialinteraction,

Ritaand Paulwere

forcedto finda substitutefortheirinformal

meansof support.Ultimately,

theyhad to rely

solelyon formalpublicassistance.

197

and Homed

FormalInstitutions

ServiceProviders

of

affectthemaintenance

Formalinstitutions

in similarwaysforthe

time-spacecontinuity

indefining

homedand homelesscommunities:

to the

socialinteraction

dailypaths,bylimiting

locale,and by providingmaterial

institutional

does not

resources.Butthehomelessindividual

have a home-baseor permanentmailingaddressto facilitateconsistentservicedelivery.

This,coupled withthe homelessindividual's

to storeand accumulateresourcesor

inability

social networksas means

to utilizetraditional

resourcesand social

ofsupport,makesmaterial

serviceprolinkedto institutional

interactions

vidersmorecrucialto well-being.Atthesame

time,accessto theseresourcesmaybe difficult

for the homeless,due to bureaucraticrules

linkingaid to keeping rigid appointment

schedules,completingjob searchesand work

of inprojects,and providingdocumentation

come and expenditures.

withserviceproviders

Ongoingrelationships

are important

sourcesoftime-spacecontinuity

formanyhomelesswomen.Accessto the serbythe factthatthe

vice provideris facilitated

withthe providisfamiliar

homelessindividual

er's dailypath,as it is definedby the service

The homeless person, however,

institution.

mustconformherdailypathto thatoftheproviderifshe is to gainaccess to thissource of

can facilitate

access,

support.Serviceproviders

and, at times,providepersonalsupport.Personal relationshipswhich go beyond the

professionalrole of the serviceproviderare

rare,but whentheydo occur theyare botha

welcomesourceofsupportas wellas a source

of positiveself-esteem.

withMrs.Smith,

Pamstruckup a relationship

the wifeof a founderof a local mission.This

statusin oballowed her priority

relationship

tainingfood and clothingfromthe mission.

Often,whileshe and Teach were livingat the

Love Camp,theywould stop in at the mission

duringthe courseoftheirdailypath,and supwith

plementtheirpublicassistancepayments

suppliesdonatedto thembythe mission.Pam

as one of Mrs.Smith'sfarelishedheridentity

voritesand indicatedthatone of the mission

workershad once been severelyreprimanded

byMrs."S" fornotknowingwhoshe(Pam)was

andfordenyingherdirectaccessto Mrs.Smith.

supportfroma

Jane,too, receivedinformal

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

198

Rowe and Wolch

social workerwiththe Los Angeles County Departmentof Children'sProtectiveServices.This

relationship not only provided material support for Janeand her family,but the personal

attentionenhanced Jane'ssense of self-esteem.

Jane:The ladyfromProtectiveServicedid somewentoversomebody'shead."Thisladyneeds

thing,

moneyrightaway."Andthatlady,blessherheart,

she gave me and mykidsa hundreddollars,her

own personalcheck,out of herown account.

Jane'sexperiences withthe service providers

did not always enhance her self-esteem,however. She related an experience with her case

worker,which occurred followingthe theftof

her purse (and all of her money)froma shelter.

She called her worker and requested that her

nextcheck be issued early.Janeexpressed frustration that her worker would not recognize

her individuality,that she was not like some of

the other women receivingwelfarewho might

use their monies to buy drugs or alcohol. By

herselffromother recipients,she

distinguishing

affirmedher identityand esteem as a good

mother and provider.

Jane:I thinkeverything

wouldgo smoothly

at ah,

the Departmentof PublicSocial Servicesifthey

treatedyou likea clientand not likesome tramp

on thestreet.... I'mnotthetypeofpersonto just,

liketheyhave thesewomenthat'sjust on drugs

and spend theirwhole welfarecheck on things

theynotsupposedto.Theydon'tpaytheirrentor

takecare oftheirkidsand that,youknow.... [Ilt's

likeyou,you'renobody,you'rejusta set of numbersto thosepeople. That'sallyouare.You'renot

human.You don't supposedto have anyfeeling.

Ifyou do you betterput themon the bottomof

yourfeet,and that'sit.

Many service recipients express frustration

in a service delivery system which they feel

refusesto recognize theirindividualneeds and

desires. The institutional/bureaucratic

routines

and the physical design of the facilityand its

interiorspace may also contributeto thisfeeling of frustrationby inhibitingthe homeless

individual'sabilityto formand maintaina continuous, friendlyrelationship with a service

provider. For example, Pam complained that

she has been shiftedfromcaseworker to caseworker,decreasing the likelihood thatshe will

establish a continuous formal or informalrelationshipwith a worker.

Cathy was actively working to reestablish

time-space continuity,by findingan apartment

for herselfand her son. But she was inhibited

bythe poor recordofthe Los AngelesCounty

Departmentof PublicSocialServices(DPSS) in

regularly

providing

thenecessaryfinances.She

complainedthatlandlordsin the Los Angeles

areawereawareoftheproblemsrecipients

encounterwithmaintaining

eligibility

and paymentsdue to DPSS policiesand procedures.

Theyare thereforeoftenunwilling

to rentto

welfarerecipients.

Cathyand JanediscussedCathy'sattemptto

findan apartment

thatshe feltwasofadequate

quality:

won'trentto youwhenyou'reon

Cathy:

[T]hey

AFDC. Unlessit'sa rathole downtownor something.Butuh, it'snota dependablesourceof income. It'smonth-to-month

eligibility.

Jane:You can get cut offat anytime,ifyou get

over twenty-five

dollarsa week you can get cut

off.Up to twenty-five

dollars,theywantthatreported,right?

in the Daily/life

Transformation

PathDialectic: Constructionof

the Homeless Identity

The deprivations

whichaccompanyhomelessnesslead manyhomelessindividuals

to place

a greateremphasison thesatisfaction

ofshorttermneeds and objectives.As a result,the esof long-term

tablishment

and fulfillment

goals

are subordinatedand supportiveelementsin

the socialnetworkcan become alienated.The

dailypathof the individualis oftenfullydedicated to meetingthe subsistencerequirementsforthatday,blockinglong-term

efforts

to escape fromthe homelesscondition.The

recursiverelationship

betweenthe dailypath

and lifepathisthusaltered,as immediate

priorities supercede the prioritiesof the life path.

Hence, the experientialbasisforself-identity

becomes static. The definitionof "self-ashomeless" becomes deeply ingrainedas the

meansand the willto escape chronichomelessness deteriorate simultaneously and syn-

ergistically.

Welfareprograms

supplyresourcesthatcan

be used to maintainor establisha home base,

butsuch programsoftenstressthe satisfaction

of short-term,

emergencyneeds ratherthan

Delong-termquality-of-life

improvements.

cisionsprovokedbycrisissituations

can disrupt

and lead

positiveclient-provider

relationships

to thewithdrawal

ofthe informal

assistanceby

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Homeless Women in Los Angeles

the serviceworker.Forexample,at one point

in her homelessepisode, the immediacyof

Cathy'sneeds required expediencyand the

oflong-range

subordination

considerations.

She

therefore

riskedlosingthesupportofhersocial

worker,withwhomshe maintained

a good relationship,

byenlisting

the aid of a welfareadvocate(Kelly)froma privateagencyto resolve

an immediateproblemwithhereligibility.

Cathy:My supervisor'smad at me, cause I took

Kellydown thereand afterthatshe ain't never

meforthat,I can'tgetnofavors

forgave

no more....

Welfareeligibility

and serviceprovisionare

oftenerratic,as we have alreadymentioned.

The constantrenegotiation

ofbenefitsand requirementsundermineslonger-runplanning.

ForCathy,thisaspectof homelessness

was deand affectedherself-esteem.

bilitating

Cathy:[Ifeel]depressed,poor,youknow.... You're

just barelymakin'it. I'm veryunhappybeingon

welfare,veryunhappy.... There'sjust no hope.

There'sno futurein it.

Supportive social networkscan also be

ephemeraland erratic,

efforts

to use

frustrating

the resourcesthey providefor longer-term

plan-making.

Forexample,lover/spouserelacan crumblequicklyundertheweight

tionships

of crushingproblemsof partners,

particularly

drugaddiction.Informal

aredisencampments

turbed,oftenleavingindividual

members

adrift.

Friendswithinthe peer networkmayrespond

to personalproblemswithmobility;

theymay

be jailedor institutionalized

or theirhomeless

episode can come to an end upon finding

accommodation.Panhandlingcontactscan disappear or be lostas the panhandleris forced

to relinquishher habitual

by local authorities

location.AsCathyand Pam'scases indicate,rewithserviceproviderscan be dislationships

turbedboth by the pressof immediateneeds

and bybureaucratic

fiat.

Thisinstability

in networksupportsleads to

frequentsubstitution

amongavailablesupport

sources,whichinitselfdemandsimmediate

attentionand divertsenergiesawayfromlongterm strategiesfor reentryinto the homed

mainstream.

The resultis prolonged homelessnessand a transformation

in identityand

self-esteem.

Such substitution

betweenmembers of supportivenetworkswas a common

copingmechanism

forthewomeninour sample,e.g.,thesupportoffellowmembersofthe

LoveCampfilledthegap leftbythedissolution

199

of Lisa'smarriage.

Hersubsequentrelationship

withMatt,in turn,helped her cope withthe

dispersalof Love Camp.Ritaand Paulalternated betweenthesupportofpanhandling

clients

and socialserviceproviders.When Teach was

jailed and faced extradition

to anotherstate,

Pam was forcedto turnto social servicesto

provideforherdaughterand herself.

Successin meetingimmediatedailyneeds is

not withoutcost, however.While effectively

copingwithsurvivalneeds can be a sourceof

positiveself-worth

and personalidentity,

the

identity

beingreinforced

is the"self-as-homeless" or "self-as-recipient."

Thus,Pam'sability

to manipulate

thesocialservicesystem

gaveher

a senseofindependence,accomplishment

and

success;but she was stilla recipientand continuedtofacetheday-to-day

ofhomestruggle

lessness.The devaluedand degradedSkidRow

localealsocontributes

to thelossofself-esteem

and theadoptionofa "self-as-homeless"

identity.Ritadiscusseshowthephysicaldesignand

temporalorganizationof a PaymentOfficeof

the Los AngelesCountyDepartmentof Public

SocialServicescontributes

to thefrustration

of

bothclientsand socialworkers.The partitioningof the space createsphysicaland psychologicalbarriersbetweenthe clientsand staff.

Thisseparationinhibits

informal

socialcontact

and reinforces

the homelessindividual's

definitionof selfas recipient.

Rita:That'sterrible,

thesepeople haveto standin

thatline forso long,and they'vegot too many

windowsfordifferent

things,too manywindows.

It's too confusing,

too manynumbers,that'sall

they'recallingall daylongis numbers.... There's

nothingbut confusionand chaos all day long in

thatplace and it'sverymentally

to the

disturbing,

fullestdegree,especiallywhenyou'rein need.

Rita's husband Paul indicates the recursive

relationshipbetween self-imageand the locale

of Skid Row.

Paul:A slumarea isa slumattitude,

theycan keep

youina slumattitude

bykeepingyouinslumplaces.

Notgivingyoutheopportunity

to do nothing....

Whenyougo intothoseold hotelsdownthereand

there'scigarettebuttsall overthe floor.So when

you'resmoking,you automatically

throwa cigarettebuttonto the floor.It'sthere,so one more

isn'tgoingto hurt.Andit'snotgoingtogetcleaned

up, so who reallycares?

The devalued natureof the locale was not

passivelyaccepted by the membersof Love

allow

Camp,however.Informal

encampments

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rowe and Wolch

200

_S4-~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

7 Clean-upDayattheprkonFta

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~A

D__~~~~~~~~~0

I'm

~ ~

[~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~I

Figure7. Clean-upDay at the parkon Firstand Broadway.

homelessresidentsto investtimeand energies

in improving

the camp'senvironsby cleaning

and keepingtentsand belongingsinorder(Fig.

7).Thepridedisplayedinthecamp'scleanliness

Skid Row streets

relativeto the surrounding

as

enhanced the camp members'self-worth

contributing

citizens.

Lisa:We gotthe cityto say"Look,you'redoinga

betterjob cleaningup." Becausewhentheyused

to come down, our street was spotless ....

They

would bringus down hoses,brooms,degreaser,

whateverwe needed.... [W]ewouldmoveallour

stuffinto the street,... and scrubthe sidewalk

down.... [Ejverybody

wascleaningouttheirtents,

gotreallycleaned

sweepingstuff

out,so everything

out....

However, the camp became so supportive

thatresidentsattemptedto remainon the sidewalk and build quasi-permanent structures

(plywoood "homes") as a personal long-term

"solution" to a more transienthomeless existence. The intentwas not to rejoin mainstream

society, but instead to remain as a member of

a homeless streetcommunity.This strategyultimatelybackfiredwhen itconflictedwithpublic policy goals:

Lisa:That'sanotherreasonwhytheythrewus off

structhe streets.Becausepeople had permanent

structures.Theyconsideredthetentspermanent

witha nailtheyconsidereda

tures... anything

... too manystartedmaking

structure

permanent

homes,and you know,you can't do that.It took

so longforusto buildthatupandtookfiveminutes

to tearitdown.

Daily pathswere also affectedby camp members' complacent attitudetoward theircircumstances. The visibilityof the encampment allowed the group to receive and accumulate

donated goods. Many more homeless people

came to the encampment after it generated

media attention,swelling the size of the community.This, along with the camp's growing

resource base, encouraged residents to alter

theirdailypathsand spend almost all theirtime

at the encampment, partiallyor totallyaban-

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Homeless Women in Los Angeles

doning other subsistencestrategies.Instead,

membersgrewrelianton donatedprovisions.

Lisa is criticalof thischange in behaviorand

the dependencythataccompaniedit.

Lisa:Wegottoobig,peoplestarted

getting

greedy,

whenpeoplestarted

believing

thatsomebody

owes

you something,that's when your attitude

changes....

Formostindividuals,

thehardships

ofhomelessnessin the Skid Row environment

transformpersonalidentity

self-worth.

and diminish

The ongoingsupportiveelementsof homeless

social networksstandin the wayof totalmaterialand emotionaldevastation,and constitutethesole brakeon a downwardspiraling

of

personalvalueand identity.

Homelesswomen

in our samplestressedthe importance

oftheir

socialrelationships,

and the time-spacecontinuitythoserelationships

provided,inpreventinga completecollapseofpriorpersonalidenAfter

a failure

tityand self-esteem.

oftraditional

social networksto provideadequate support

and thuspreventthe onset of homelessness,

the homelesssocialnetworkprovedso critical

to materialand emotionalwelfarethat the

as "homelesscommuadoptionof an identity

nitymember,""panhandler,"or as a service

provider's"favorite"was readilyembraced.

Whilethe acceptanceof these new identities

servesa positivefunction

inmeetingdailyneeds

and maintaining

self-esteemwithinthe geographicand social contextof homelessness,it

worksagainstdevelopingboththe means,and

the will,to execute long-term

projectsaimed

at reentering

mainstream

society.

Summaryand Conclusions

Our findings

revealthe fundamental

structure of social networksamong the homeless

womenin oursampleand providecluesabout

the networksof homelesspeople more generally.The women's networkshave peer and

homed sub-parts,both of whichare typically

removedfromtheir

sociallyand geographically

priorresidentialcommunity.Both peer and

homednetworks

are centralin helpinghomelesswomenreestablish

time-spacecontinuity.

The rebuildingprocessproceeds byreplacing

ofa spatially-fixed

thefunctions

home-baseand

social interactions

workplacewithsignificant

occurringat variablelocations.Such interac-

201

tionsinvolvefriends,

family,

or a lover/spouse;

encampmentcommunities;panhandlingpatrons;and socialserviceproviders.Forhomelesswomen,lover/spouse

relationships

notonly

provideemotionalsupport,but likea homebase,supplyprotection

and a constantpointof

referenceinthedailypath.Informal

streetencampmentsare more directhome-basesubstitutes,

despitethe factthattheyare subject

to enforcedmobilityby police sweeps. Panhandlingand socialserviceprovidersfunction

likea job in threeways,byproviding

cashand

in-kindincome,bystructuring

the individual's

dailypath,and bycreatinga set of socialcontactswhichcanandoftendo provideemotional

and materialresourcesbeyondgivingalmsor

publicassistancegrants.

Like their homed counterparts,homeless

womenactivelysubstitute

relianceon one social networkmemberforanotheras everyday

exigenciesand geographicalaccessibility

demand.Panhandling,

suddenlyprohibited,

is replaced by publicassistance;one serviceprovideris replacedby another;spouses exit,to

be replacedby a lover.In thisway,homeless

womenmarshall

theirresourcesand maximize

the supportprovidedbytheirsocial network.

Finally,the impactof homelesssocial networkson personalidentity

andself-esteem

varies both withinand between networkcomponents.Socialtiesmayhavebothpositiveand

negativeeffectson self-definition

and morale.

The "self-as-homeless"

identity

maybe readily

adopted, if the experienceof homelessness

bringswithit a clearly-defined

role,recognition(as a leaderor advocate,forexample),notorietyor otherformsof attentionpreviously

to theindividual.

unavailable

Butfarmorecommon,we suspect,are devastatingimpactson

identity

and self-esteem.

Alongwiththe short

timehorizonenforcedbybeinghomeless,precarioussocialnetworks

anda threatening

locale

can alterthe individual's

daily/life

pathdialectic. Long-term

investments

forimproving

the

lifepath are postponedand resignation

to a

negative"self-as-homeless"

deterioidentity,

ratingself-esteem,

and hopelessnessare commonand difficult

to resist.Butthesupportprovided (either periodicallyor habitually)by

homelesssocial networksmayparallelshelter

itselfin its impacton the qualityof lifefor

homelesswomen.

Theresearchsuggestsa variety

ofhypotheses

and questionsto be exploredinfuturestudies.

This content downloaded from 193.198.212.4 on Tue, 24 Nov 2015 14:49:58 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

202

Rowe and Wolch

First,our samplewas small.Analyticmethods

(suchas surveyresearch)thatpermitlargersample sizes would be usefulto expand on our

researchfindings.

Second,thefocusofourethnographicworkwas homelesswomen.An obviousquestionis: how do socialnetworksand

dailypathsdifferamong homelesssub-populations?Does the compositionor densityof

socialnetworks

orthespatialrangeofdailypaths

formenandwomen,discreteage groups,

differ

racial/ethnic

minorities,

type and degree of

new homelessand old? Moreover,

disability,

insocialnetworks

do observeddifferences

and

dailypathsbetweenhomelesssubgroupshave

parallels in comparable groups withinthe

homed population?Further

analysiscould indicatethe extentto whichhomelessnetworks

in time-spaceare the resultof situation(the

homelesscondition)or stem fromindividual

or demography).

Third,

characteristics

(disability

LosAngeleswelfareand policepoliciesand the

natureoftheSkidRowenvironment

werecriticalto ouranalysis,

suggesting

thatthepolitical

economic and geographiccontextwill contributeto the structure

and functionof social

networks

and theconfiguration

of dailypaths.

How much influencedoes the locale and its

perceivedqualityexerton socialnetworkformation,and conceptionsofself?Thisquestion

shouldbe exploredbysystematic,

comparative

ethnographicresearch incorporatingtimebudgetanalysisand cognitivemappingtechniques,at a variety

of urbansites(as described

in Rowe and Wolch 1989).

Our studyalso haspublicpolicyimplications.

to assisthomelesspeople in

Concertedefforts

rebuildingtheirsocialnetworksmaybe a vital

additionto theservicearsenal.Currentservice

provisionfocuseson the materialdeprivation

ofthehomeless.Our researchsuggeststhatthe

socialeffectsof homelessnessare notonlyrelatedto materialconditions,but these conditionsare in themselvesa consequence of the

Thisimpliesthat

socialcontextofhomelessness.

the provisionof safe, neutralspace where

homelesspeople can socialize,eat, leave beand plantheirongoingactivities

may

longings,

be valuable.Models forthistypeofspace may

includeprotectedvest-pocket

parksand dropincenters(see Cohen and Sokolovsky

1989for

a description

ofa drop-inprogramtargetedto

elderlyhomelessmen of New York'sBowery

district).Transitional,

congregateand communityhousing would provide time-space

the buildingof social

continuity

and facilitate

faced

muchoftheisolation

networks,

alleviating

homeless,and providethem

bythe (formerly)

in their

witha measureof self-determination

These housingprograms

livingenvironment.

only address the needs of a portionof the

due to thelimitednumhomelesscommunity,

of the

ber of availableunitsand the diversity

homelesspopulation.The designationof selected geographicalareas for homeless encampmentswould reinforcesocial networks

forthose who are

and time-spacecontinuity

unable to secure traditionalor congregate

proposal,

housing.Thisis a morecontroversial

oppositionwhichwould

giventhecommunity

located and

likelyresult,but ifappropriately

in size,oppositioncould be mitigatrestricted

ed.

The recoveryof social networksamongthe

homelessis essentialto solvingone of their

to organize.

mostcriticalproblems:theinability

Fromthisperspective,

theadoptionofa "selfcanactuallyprovidea baas-homeless"identity

sis by which homelessnesscan be ultimately

transcended.Throughrecognizingtheircomand organizinghomeless

mon circumstances

actiongroups,theotherwisediversehomeless

community

maybe able to forma socialmovementtargetedat placingtheirdemandson the

politicaland

politicalagenda,and influencing

serviceprovisiondecisionswhicheffecthomelessness.The currentlackofhomelesspolitical

powerleads policymakersawayfrommeeting

theirneeds forgreaterassistance,such as additionallow-costhousing,social services,job

trainingand employment.Thus the powerand exaclessnessof the homelessreinforces

homelesspeople

erbatestheirplight.Assisting

to rebuildtheirsocial networkscan empower