Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Improving Schools-2014-Szczesiul-176-Exploring The Principal's Role in

Uploaded by

alanz123Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Improving Schools-2014-Szczesiul-176-Exploring The Principal's Role in

Uploaded by

alanz123Copyright:

Available Formats

534545

research-article2014

IMP0010.1177/1365480214534545Improving SchoolsSzczesiul and Huizenga

Article

The burden of leadership:

Exploring the principals role in

teacher collaboration

Improving Schools

2014, Vol. 17(2) 176191

The Author(s) 2014

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1365480214534545

imp.sagepub.com

Stacy Szczesiul and Jessica Huizenga

University of Massachusetts Lowell, USA; Cambridge Public School District, USA

Abstract

Based on qualitative data collected over a 6-month period, this article examines how teachers experiences

of principal leadership practice influence their capacity to engage in meaningful collegial interactions during

structured collaboration. Similar to previous studies, our findings confirm the limitations of leadership that

relies primarily on structural changes to foster collaboration. Our findings contribute further to leadership

research by presenting teachers perspectives on why particular principal leadership practices matter to

teacher collaboration and by illustrating how the principals enactment of leadership practices influences

teachers sense of efficacy and motivation, both of which are critical to professional learning during

collaboration.

Keywords

Principal leadership, teacher collaboration, teacher efficacy, teacher motivation

Introduction

Since the 1980s, scholars have documented the positive effects which teacher collaboration can

have on teachers and schools (Johnson, 1990; Little, 1982, 1990; Rosenholtz & Simpson, 1989).

More recent research suggests that when teacher collaboration includes reflection and feedback

on student learning, it can also have a positive effect on teaching practice (Garet, Porter,

Desimone, Birman, & Yoon, 2001; Stoll, Bolam, Wallace, McMahon, & Thomas, 2006) and

student achievement (Goddard, Goddard, & Tschannen-Moran, 2007; Johnson, Kraft, & Papay,

2012). As a result of this empirical support, schools are increasingly introducing collaborative

structures as a way of fostering meaningful collegial interaction and instructional

improvement.

Many US secondary schools now use what is widely referred to as common planning time to

facilitate collaboration between teams of teachers (Kellough & Kellough, 2008). Typically made

Corresponding author:

Stacy Szczesiul, University of Massachusetts Lowell, 61 Wilder St. Lowell, MA, 01854 USA.

Email: stacy_szczesiul@uml.edu

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

177

Szczesiul and Huizenga

up of two or more teachers from different core curriculum areas who serve the same students, the

teams are expected to use this time to plan ways to integrate the curriculum, analyze assessment

data, examine student work, discuss current research, and reflect on the effectiveness of instructional approaches being used (National Middle School Association, 2010, p. 32). While over two

decades of structural reforms have failed to improve US secondary schools, attempts to bolster

teacher collaboration through common planning time bring renewed hope for improvement because

of a focus on the social processes that occur within the collaborative structure. Thus, initiatives

such as common planning time are thought to have the potential to unlock critical social technology that historically has been underused in schools (Mertens, Flowers, Anfara, & Caskey, 2010).

Specifically, social interactions among teachers during common planning time are thought to promote the following: the expectation that teachers place student needs and progress at the center of

their work; the development of shared norms for behavior and academic performance; and opportunities for continuous improvement that are job-embedded, focused on relevant topics, and

anchored in reflective processes.

However, while studies find that giving teachers regularly scheduled time to meet is critical to

their collaboration, this alone does not guarantee that their efforts will result in instructional

improvements (Levine, 2011; Little, 1990, 2002). The likelihood that meaningful interaction will

occur depends instead on whether a schools professional culture supports collaboration and on

whether teachers have the efficacy and motivation needed to engage in collaborative work

(Bandura, 1997; Geijsel, Sleegers, Stoel, & Krger, 2009; Goddard, Hoy, & Hoy, 2000; TschannenMoran & Hoy, 2001). There is general consensus in leadership research that principals can foster

an effective culture of collaboration through leadership practices and that, through these practices,

they can also positively impact teacher efficacy and motivation (Leithwood & Jantzi, 2006).

However, more research is needed to understand fully how the enactment of successful leadership

practices influences teacher readiness for collaboration (Giles, 2007; Marks & Printy, 2003;

Runhaar, Sanders, & Yang, 2010). The contribution of leadership research should be to identify the

practices that are most effective in their impact on teachers and students and to explain why they

work. It is the combination of description, practical example, and theoretical explanation that

contributes to a more robust understanding of effective leadership practice (Robinson, 2007, p. 5).

This article, therefore, draws on data from a qualitative study of four teacher teams to answer the

following research questions: How are teachers collaborative experiences during common planning time mediated by principal leadership? In what ways do specific practices and the ways in

which the practices are enacted by principals influence teachers sense of efficacy and motivation

during collaboration?

Principal leadership and teacher collaboration

Strong leadership is one of the most significant factors in determining whether meaningful professional collaboration occurs in a school (Marks, Louis, & Printy, 2000; Youngs & King, 2002).

As such, the most effective principals are those who modify structure while also strengthening

school culture in order to create optimal conditions for teacher collaboration (Giles, 2007; Talbert,

2010). Put another way, effective leaders are those who influence the behavior and attitudes of

others in their organization through both formal and social controls (OReilly & Chatman, 1996).

School administrators, however, historically have relied primarily on formal controls directives

and rules, prescribed routines, structural changes, and sanctions for noncompliance to coordinate and promote collaborative activity among teachers (Talbert, 2010). Studies have repeatedly

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

178

Improving Schools 17(2)

documented the ineffectiveness of using formal controls to implement complex processes such as

teacher collaboration (King & Bouchard, 2011). Indeed, such efforts to influence collective

behavior do little to create the patterns of collegial interaction needed to sustain learning among

teachers (Malen & Rice, 2004; ODay, Goertz, & Floden, 1995), and their impact can in fact be

detrimental to teacher motivation (Ingersoll, 2003; Talbert, 2010).

Scholars, instead, suggest that leaders develop commitment to organizational outcomes through

informational and social influence, thereby guiding the behavior of people in collectives (Martinez

& Jarillo, 1989; OReilly & Chatman, 1996). Leveraging social processes to collectively define

what is important to the organization and to identify appropriate attitudes and behaviors to guide

its members is critical to creating a strong culture. It therefore is a pivotal leadership task. Practices

associated with building a strong culture of collaboration are consistently cited in research dedicated to school-level leadership (Leithwood, Louis, Anderson, & Wahlstrom, 2004). Importantly,

these leadership practices, when executed effectively, also bolster teachers motivation and efficacy and help them to persevere through difficult conversations with their colleagues (Runhaar

et al., 2010).

First among these practices is establishing a vision of academic success for all students that is

based on high expectations, rigorous standards, and clear school goals (Leithwood et al., 2004).

How principals carry out this practice has implications for teacher commitment; teachers are not

likely to internalize mandated values or a prescribed routine (Pascale, 1990), but by identifying and

promoting agreement on organizational vision, goals, and values, school leaders reinforce teachers personal and social identification with the organization, thereby creating a sense of cohesion.

This increases the likelihood that teachers will exchange knowledge and ideas with colleagues in

the context of structured collaboration (Geijsel et al., 2009; Runhaar et al., 2010). Indeed, there is

considerable empirical evidence to support the claim that internalizing school goals as personal

goals can increase teachers self-efficacy and their willingness to engage in collaborative exchanges

with their colleagues (Geijsel et al., 2009; Runhaar et al., 2010; Thoonen, Sleegers, Oort, Peetsma,

& Geijsel, 2011). Collaboratively creating and promoting a vision for the school thus plays an

important role in motivating teachers, particularly when principals involve them in decisionmaking (OReilly & Chatman, 1996; Thoonen et al., 2011).

Research also suggests that principals who provide teachers with support and intellectual stimulation help to create a culture of collaboration and continuous improvement (Leithwood et al.,

2004; Thoonen et al., 2011). By acting as a role model and coaching their teachers, principals signal what is important to the organization, reduce feelings of uncertainty and vulnerability, and

increase the likelihood that teachers will engage in difficult conversations about practice with their

colleagues. Moreover, by encouraging teachers to question their own beliefs, assumptions, and

values and enhance [their] ability to solve individual, group, and organizational problems, principals foster the belief that improving the quality of education is both an individual and a collective

enterprise (Thoonen et al., 2011, p. 508). Scholars further contend that when principals employ

these leadership practices and buffer teachers from issues unrelated to their practice, they foster

collaboration and a climate of trust in their leadership, which is a foundation for creating other

forms of trust, and it allows the school to manage its critical human resources more effectively

(Tschannen-Moran, 2004, p. 198).

Analytic framework

In this study, we sought to understand which leadership practices mattered to teachers as they

engaged in collaborative activity during common planning time. We also sought to understand how

the enactment of practices might facilitate or obstruct teacher collaboration. Specifically, we

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

179

Szczesiul and Huizenga

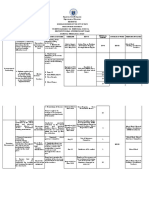

Figure 1. Analytic framework of leadership practices and means of enactment.

wanted to know how principals use of both formal bureaucratic and informal social processes

might influence teacher efficacy and motivation as well as their internalization of values, attitudes,

and behaviors associated with collaboration. We relied on Leithwood et al.s (2004) core leadership

practices to aid our analysis of which leadership practices matter to teachers. Taken together, these

core practices assume that teacher workplace performance is a function of teacher motivation,

ability, and situation (Leithwood & Jantzi, 2006, p. 17). Leithwood and Jantzis conceptualization

of leadership practice is anchored in a substantial research base that cuts across school and nonschool sectors. As such, it accounts for various empirically validated leadership models that rely on

both formal and informal approaches to organizing teachers work. Yet, because research on these

core leadership practices tell us little about how they are enacted by principals (Giles, 2007;

Kennedy, Deuel, Nelson, & Slavit, 2011), we included in our framework both informal social

approaches to leadership and those considered more formal and bureaucratic (Talbert, 2010).

Formal approaches include, for example, written policies, rules, job descriptions, and standard

operating procedures, while informal social approaches might include consistently communicating

and modeling core organizational values and norms, using inquiry and dialogue to help others

make sense of organizational events in light of core values and norms, and positively and publicly

reinforcing organizational members commitment to values, attitudes, and behaviors that are consistent with desired organizational outcomes (Wahlstrom & Louis, 2008) (Figure 1).

Methods

We spent 6 months interviewing teachers and observing their team processes during common planning time in two schools located in the northeastern United States.1 Walsh Middle School served

751 students in grades 68 who were predominately White and middle- to upper-middle-class. The

principal had been at his post for 5 years, and the school was moving into its fifth year of common

planning time for content-area teaching teams. According to state data, Walsh consistently maintained a high performance rating, but it was struggling to meet state performance targets for its

special education and low-income students. Greenpark High, which also had a predominately

White, middle- to upper-middle-class population, served 1021 students in grades 912. The principal had been in her post for 5 years, and she had introduced common planning time when she

arrived. Greenpark consistently ranked in the top 15 high schools in the state. We purposefully

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

180

Improving Schools 17(2)

Table 1. Summary of study participants and teacher teams.

Walsh teacher

Team

Years

teaching

Years on

team

Greenpark

teacher

Team

Years

teaching

Years on

team

George

Alex

Bill

Gerry

Raymond

Olivia

Gretaa

RJ

Catherine

SS

SS

SS

SS

SS

SCI

SCI

SCI

SCI

18

7

14

13

8

1

11

8

4

4

4

5

1.5

2

1

5

0.5

1

Mildred

Miles

Joe

Gina

Simon

Townes

WH

WH

WH

EN

EN

EN

3

9

12

15

4

7

3

3

3

0.8

4

4

SS: social studies; EN: English; SCI: science; WH: world history.

aReturned from maternity leave to participate in the final observation and an individual interview.

selected these two schools because their administrators allocated time for teachers to meet and

provided professional development focused on collaboration, both of which are critical to collaborative processes that result in teacher learning (Main, 2012; Scribner, Sawyer, Watson, & Myers,

2007). We also wanted to investigate how principals motivated teachers to collaborate with their

colleagues despite a lack of external pressure or any sense of urgency (Mourshed, Chijioke, &

Barber, 2010).

The four teams, two from each school, included teachers at different stages of their career. This

was important to our investigation, because the research has not addressed the critical mass of

experience and expertise needed for effective collaboration (Talbert, 2010). We were also interested in how differently leadership practices might affect teams at various points in the collaborative process (Levine, 2011; Slavit, Kennedy, Lean, Nelson, & Deuel, 2011), so we selected teams

with varying levels of experience working together (Table 1).

We collected data through a variety of qualitative methods: audio and video recordings from

four meetings of each team; post-observation reflections; two focus group interviews per team;

individual teacher interviews; individual efficacy surveys; and principal interviews. Based on survey data, analytic memos, and field notes kept throughout the data collection, we drafted case

studies of each team to create a full account of the membership, the nature of the teams collaborative work, and the broader school context in which teamwork was embedded. Themes related to

principal leadership and teacher capacity for collaboration were prominent in our case studies,

which helped us develop our theoretical framework.

We coded interview data thematically for core practices, attending specifically to teachers

descriptions of how their principals carried out the practices (e.g. whether a principal attempted to

build commitment to collaboration by changing school structure and introducing standardized processes and/or by engaging teachers in a dialogue about what purpose collaboration might serve and

what behaviors would foster meaningful collaborative work). We then looked at how teachers

descriptions of principal leadership practices related to the levels of efficacy and motivation they

described bringing to their collaborative interactions with colleagues during common planning

time (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). We followed by analyzing our observation data to uncover any

further relationship between principal leadership practices and teacher efficacy and motivation. We

then cross-checked teachers descriptions of principal leadership with principals self-reports from

the interview data and coded video transcripts of common planning time meetings for evidence of

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

181

Szczesiul and Huizenga

interactions that supported or challenged patterns that had emerged earlier. We carried out this

process for all four teams, noting patterns within and across teams.

Findings

Consistently emerging across all four teams was teachers desire for principals to establish much

needed direction for teacher collaboration. They noted principals lack of attention to social processes and a reliance on formal approaches to promote collaboration (i.e. mandating that teachers

meet in assigned teams to create common assessments, use assessment data to inform instructional

decisions, and submit either documentation of their progress or the assessment data as a proxy for

documentation). Overreliance on mandates, rules, and standard operating procedures did little to

foster positive attitudes about collaboration among the teachers. Moreover, what teachers perceived as the principals lack of vision undermined the teachers confidence and motivation to

work together on problems related to instruction and student learning.

Because the principals did little to set the direction for collaborative work, the teachers were left

to define the goals of and expectations for collaboration in the isolation of their own teams. This

placed a heavy burden on the teachers, and depending on the leadership capacity within the team,

they either struggled or failed to fulfill them. In the following sections, we present and discuss our

findings, illustrating the principal leadership practices that teachers identified as critical to collaboration, and how the absence or poor execution of these practices shaped teachers experiences in

common planning time. Furthermore, we present and discuss data that illustrate how the teams

differential capacity to provide leadership on their own affected what the teachers gained from

their collegial exchange.

A vision of collaboration that combats the culture of complacency

Across teams, the teachers described a lack of administrative vision as one of their biggest frustrations. While they were provided time to collaborate and given training in assessment development

and data analysis, they longed for their administrators to introduce a framework for teaching and

learning that would eliminate the guessing game [about] expectations for instruction and assessment, as Joe, a Greenpark teacher, explained,

Take something like Montessori, whether you agree with it or not, if you are in there as a teacher you know

exactly what your expectations are going to be because that philosophy truly defines everything that goes

on there and its clear.

Teachers were also looking for goals to give them purpose, guide their collaborative work, and

mark their progress. Greta, a Walsh teacher, underscored the motivational power of having a

school-wide goal tied to a vision of teaching and learning:

We need to set a goal that were all working towards, like, Our goal is to improve student achievement.

We want somebody to say, This is the data that we currently have based on our grades . . . our goal is to

change that in the next year, and lets analyze it again at the end of next year and see. So we have some

sort of motivation of why were [collaborating].

Both principals in the study acknowledged their lack of leadership in providing direction for teachers collaborative work. The Walsh principal admitted that he didnt do a good job presenting the

vision, even though he felt urgency . . . that there needed to be changes. The Greenpark principal

said she needed to raise the level of urgency and to clearly communicate that this is our focus.

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

182

Improving Schools 17(2)

Without this direction, teachers were left questioning what they should be doing during common

planning time and what they should say to colleagues who wanted to know why such an effort was

necessary. Alex wanted his principal to help him and other teachers from Walsh Middle School

answer questions like Why am I doing this? Is it to close the achievement gap? Is it to ensure that

all children are learning? Teachers at both schools asked these questions, and both principals recognized that their schools high performance had created a culture of complacency among teachers. According to Miles, however, no one including the principal at Greenpark talked about how

easy it was for teachers in the district to hide behind good scores. His colleague Joe agreed,

explaining that the reality behind growth in student performance over the past decade was the

result of serving families with money: They somewhat value education, they are going to grow

up literate. [So], even if some mediocre stuff goes on, we still kind of stumble upon some

success.

From the teachers perspective, if their collaboration during common planning time was to bring

about real change in their teaching, the principals needed to make it clear that there were student

learning problems and they urgently needed to be addressed. George, a middle school teacher from

Walsh, explained that if the teams were really responsible for something, like setting goals for

improvement, they would double down on [i.e., increase their] motivation and be more invested

in collaborating. But because their principals led the collaboration solely by mandating a time to

meet and requiring the use of specific practices (such as using data and developing shared assessments), the teachers had no opportunity to confront the relationship between privilege, high performance, and the need for instructional improvement. As a result, according to the teachers in the

study, there was no discussion of shared goals, and many of them did not grasp the purpose of

collegial collaboration. Without pressure to improve or an understanding of the value in doing so,

teachers had little motivation to collaborate effectively.

A vision of collaboration that aligns with professional development

A lack of shared purpose, goals, and expectations among the teachers resulted in a lack of clarity

about how to resolve problems of practice through collaboration. Formal professional development

for teachers exposed them to external experts who introduced them to technical processes for

developing common assessments and interpreting data, but did not necessarily help teachers

uncover or address the underlying problems of student learning. This often produced more questions than solutions and left teachers frustrated with the process and unwilling to engage in hard

conversations about practice.

The Walsh social studies team epitomized a need for more guidance and support from the principal as they grappled with the problem of having high academic standards for students with special needs. While analyzing data on one assessment of students ability, the team acknowledged

that not all students were able to perform to the same high standard of performance. They questioned whether they should adopt the professional developers recommendations they were given

by outside consultants during professional development to maintain the same standard for all

students, whether they have special learning needs or not or to go with the special education

departments suggestion and adjust the standard for students with unique challenges. George

pointed out why this was a problem, explaining that teams were instructed to set goals or standards collaboratively but that they got mixed messages about whether the standard should move

based on a students needs:

We have heard the message of [professional developers] . . . the standard is set and . . . the work with the

child varies to meet the standard. But in . . . some of the special ed discussions, its move the standard . . .

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

183

Szczesiul and Huizenga

And so somebody may need to . . . say either were going to use this philosophy or were going to use that

philosophy. Thats what were doing.

George and his colleagues argued that the teams could not resolve this issue on their own. The

principal needed to establish an overarching philosophy or vision for addressing the needs of all

students, which would require a talk with teachers about the role of standards in assessing students

with special needs. The teachers also needed professional development that would help them apply

principles that were consistent with the overarching vision in their practice. But, as Alex explained,

they were looking for some guidance that just isnt there.

Uncertainty about how to support students at the low end of the spectrum and where to turn for

answers made teachers feel incapable of addressing important problems of practice. It also undermined their motivation to even ask questions about the problem during common planning time. At

Greenpark, Miles kept expecting his principal to provide the supports they needed, but she had not.

This had an observable impact on teachers belief that they could persevere in the face of these

problems and on their willingness to delve deeper into them. In fact, all four teams preferred to

avoid the problems altogether. Townes, a high school teacher, represented the feelings of others in

the study, saying that when his team faces real challenges, they just sort of move to the next thing

because they dont really have anything to offer. While both principals assumed that putting

teachers on teams, scheduling time for them to meet, and providing professional development on

assessment and data use would be enough for the teachers to just run with common planning time,

the teachers in the study consistently stated that the principal needed to be more actively involved

in providing support that was consistent with an overarching vision and that would help them

address immediate problems of student learning.

A vision of collaboration that monitors progress and drives

accountability

Teachers at both schools said their principals attempted to track the work of the teams. Greenpark

teachers were asked to list their meeting times and places and what they hoped to accomplish and

they had to submit their midterm assessments as a proxy for progress. The principal at Walsh

required the teams to complete a form that described the common assessment they created or the

assessment data they analyzed during their meetings. According to teachers, because their principals did not offer feedback or follow-up on their work or the assessments, this approach did little

to support their collaborative work, promote a culture of professional learning, or hold other teachers accountable for progress. Matt explained,

We ask for feedback and we dont get it. And sometimes thats very frustrating for us because well fill out

the forms; well write the right questions, like What should we do next? And not only do the forms not

get returned, but the questions dont get answered. So that in itself is a little bit uninspiring.

Teachers also had mixed feelings about the forms required at Walsh, describing them as a double

edged sword. At both Walsh and Greenwood, there was tension between a desire for guidance and

feedback, that is, that their work be monitored and a desire to be left alone. Raymond explained,

On the one hand, we are not getting a lot of guidance thats really helpful because we are not getting any

guidance really. But on the other hand, . . . other than the form you have to fill out which is not that

unreasonable and they havent been very demanding at all about it once we start putting them in whatever

we put in was fine with them.

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

184

Improving Schools 17(2)

Raymond and his teammates wanted more guidance and support, and they hoped that filling out the

form would motivate the principal to attend to their needs. It did not, however, and this was in some

ways a relief to the team because it meant they could use common planning time to satisfy the

survival needs of new teachers rather than dealing with assessment practices. All teachers in the

study said that management tools (like the form) intended to track the teams needs and hold them

accountable for collaborative work were phony. Gina, Greenpark teacher, explained,

So, you want minutes of the meeting, you get minutes of the meeting . . . They will have nothing to do with

what really went on in the meeting . . . You go write the minutes and you hand them in and they go in a file

in the principals office and they sit there for 15 years, and then they throw them away . . . So its phony

accountability.

The principals lack of follow-through denied teachers the support they needed and wanted, and it

allowed teachers who were less invested to opt out of the work altogether. According to Mildred, a

lot of Greenpark teachers were frustrated at how this teacher is not willing to use the same assessments or this other teacher doesnt come to the common planning. Her teammate Miles admitted

that he gets frustrated when other groups arent working [and the] administration allow[s] them to

continue to do their own thing. He argued that participation in common planning at Greenpark

should not be on a voluntary basis and that teachers who do not participate should be nudged by

the principal, especially when other members of the team are working to make collaboration and

collective improvement a priority:

Somebody should tell that outlier [non-participant], Hey work with the team. I have no control over that,

but I feel a little like there are other people who want this . . . Sometimes the administration needs to nudge

more.

Indeed, Greenpark teachers characterized the principals hands-off approach to monitoring collaboration as a game the teachers and the principal played during common planning time. Joe

compared it to the implicit social contract between teachers and students that he believed was at

work in many Greenpark classrooms:

I call it the deal or the game, which basically means, Im not going to be too hard on you, and you are not

going to misbehave in my class. We are going to have fun, some jokes, [everyone] is going to get decent

grades, so no one complains, and I dont have too much work to bring home, you dont have too much to

bring home.

This lack of oversight reinforced the symbolic purpose that redesigning organizational structure

can serve, thus promoting a logic of confidence between the school and its constituents (Elmore,

2004). However, it did little to affect the agentic possibility restructuring offers; it instead demotivated teachers and put teacher collaboration in jeopardy. Miles spoke for many when he said,

Look, Im on board, but it sort of undermines the whole thing when you feel it doesnt matter.

Carrying the leadership burden

Principals from both schools created structures to promote collaborative activity among teachers.

They also mandated standard assessment processes that teachers received training on during externally led professional development. Both teachers and the principals remarked that these efforts

failed to create a cultural context that would bolster teacher efficacy and motivation and support

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

185

Szczesiul and Huizenga

meaningful collaborative work. Moreover, all the study participants reported wide variability in

how the teams carried out the mandate for collaboration during common planning time. The Walsh

principal saw that some groups caught on right away, while others were still trying to find their

way. Similarly, the Greenpark principal recognized pockets [teams] in the building that werent

working so well.

We observed this variability across the four teams in our study; the Walsh teams were doing well

with it, but Greenpark teams were not. Teachers on the Walsh social studies team were experienced, extremely confident in their practice and that of their colleagues, and they had been together

for more than 3 years. In that time, they had created a context of interdependent, strength-based

work that served a common purpose, reinforced teachers confidence that they could improve, and

motivated teachers to work together. Matt described his team as being dead on (i.e. successful) in

their collaborative process, despite lacking the guidance and the vision . . . from [the] administration. Rather than waiting for direction that may never come or fighting against [collaboration],

the team defined the big picture for themselves. George explained that the teams overarching

goal of teaching history in a way that is different from what the public thinks of as a history class

kept them motivated and moving forward. It gave them a sense of identity, without which they

would be, as Alex put it, running aimlessly. Furthermore, having shared their expectations for

student learning, agreed on what content to teach and on assessments they believed would reveal

what students know and are able to do, the team members were highly motivated to work together.

When they experienced frustration dealing with students at the low end of the spectrum, the team

experimented with new practices on their own, such as using flexible grouping strategies in their

classrooms. This yielded progress for students in areas that had caused problems in the past and

gave teachers on the team a sense of success that motivated them to persist in pursuing seemingly

unanswerable questions. George reflected on the teams progress:

Weve put a lot of work into it . . . there have been times over the couple of years where we felt like we

were making tests for the sake of making a test. And, because we hadnt defined some new goals, we

werent quite as good at it. We even looked back later like, Man, we were just making tests to say we made

another test.

The team clearly had matured beyond the point of simply complying with the principals mandate

for collaboration, and together they learned the importance of setting their own goals, figuring out

how to reach students, and reflecting on their progress. This sustained process revealed to team

members the value of collective effort and helped them persist in their collaboration. The Walsh

teams commitment to improve through collective effort also mediated the detrimental effects of

teacher autonomy that often obstruct team performance. Putting data on the table at every meeting

made the team accountable to each other for meeting high standards of practice. Alex explained,

This is something that we put time into, and its worth doing, and maybe this worked, this didnt work. Just

a general accountability . . . that Im not going to guess them to death and go back and do what I want but

its deceptive, and its not the way I operate.

Thus, while accountability was lacking at the school level, it was created at the team level through

collaborative work and was driven by expectations set within the team that fostered teacher efficacy and motivation.

There was decidedly less potential for teachers to lead collaborative improvement efforts at

Greenpark, where the English team acknowledged how tricky it was for the principal to hold

teachers accountable for their collaborative work, especially at the high school. Simon pointed out

that the principal had very little . . . credibility in the eyes of teachers, and Townes concurred,

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

186

Improving Schools 17(2)

recalling how past attempts to formalize common planning time caused sort of a blowblack or

negative feelings among teachers. According to Simon and Townes, even as administrators tried to

foster collaboration, they made decisions that alienated teachers (Talbert, 2010), such as trying to

legislate collaboration from the principals office. Townes explained,

The notion that were going to, as an institution, try to legislate [collaboration] into existence for us

would be counter-productive because what keeps us as a group together is [that] we feel a certain amount

of respect for one another.

Despite their collegial regard, the English team members could not reconcile their disparate professional values, establish a shared purpose, or identify common goals that would bolster efficacy and

motivate them to establish a context for collaborative improvement. After a year of working with

his colleagues during common planning time, Simon carefully suggested to his colleagues, We

want to be careful to be more closely aligned [next year] than we were in the spring semester. He

continued tentatively,

Im not saying we have to be lock step . . . but I do think just from the standpoint of material, its important

that we try to commit to doing the same things. And it might require some more careful planning and

sharing of what we want to do.

Townes, responded emphatically, Im still not sure what purpose does it serve? While Simon

conceded that he was feeling pressure from outsiders to coordinate the teams work more, other

team members had no understanding of (or interest in) what it would mean to be aligned beyond

what texts to read and standards to address. Towness question about purpose underscored their

lack of understanding of the benefits of interdependence to both teachers and students. Gaining this

would require the principal to lead a school-wide discussion that would push teachers to explore

their own values and test their own assumptions about the relation between teacher collaboration,

instructional improvement, and student learning.

Members of the English team also offered reasons for not sharing individual problems of practice, including that teachers are all different and they typically know when things dont go well

and why. The teachers said their ideal collaborative exchange was open-ended discussions, conversation filled with questions, and debate. However, because team members did not share professional values or practices, their discussions, questions, and debates remained superficial and

focused on individuals. The teams lack of principled talk about practice (Horn & Little, 2010) did

little to help individual teachers resolve problems of student learning, and their exchanges during

common planning had the potential to erode rather than foster teacher efficacy and motivation.

This was evident in a conversation Gina had with her teammates about her intention to take her

college-prep students through the novel Great Expectations. Simon called her decision ambitious, and Townes chimed in with admirable. Gina got the sense that her teammates felt it was

crazy to teach that book because of the difficulty of the text would demand too much from her

particular group of ninth graders. Simon qualified his comment,

[It] is not to say that youre completely insane for trying this because you obviously have a strong

confidence level with your with this text. You know, based on my experience with the majority of our

students at that level, I think its going to be a big leap.

According to Gina, they essentially were asking arent you biting off more than you can chew?

As the discussion ensued, questions were not about making the novel accessible to all students but

about whether the novel was above the heads of college-prep ninth graders. There was no

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

187

Szczesiul and Huizenga

discussion of what an accessible unit on Great Expectations might look like for these students, nor

did they engage in collective problem-solving to anticipate solutions to some of the challenges

Gina might face. The result was that Gina would teach this book on her own terms, thus providing

a very different experience for her students than for those of the other members of her team. Simon

and Townes inadvertently made value judgments about the students ability to learn and Ginas

ability to teach such a complex text to ninth graders. Gina said it provoked her to think more deeply

about the challenges of teaching Great Expectations, but it also made her question her expectations

for student learning and her own efficacy. Moreover, she would take on this challenge in isolation,

as her team did not choose to experiment with exposing students at that level to more challenging

texts perhaps because they did not want to confront their own beliefs, assumptions, and practices.

Furthermore, Gina might have felt more confident had her colleagues told her that teaching such a

text to her students was possible or if they had told her how they had accomplished similar feats in

the past (Bandura, 1997). For Gina, this exchange likely had little positive effect on her belief that

she could tackle Great Expectations or on motivating her to talk to her colleagues in the future

about what she might try in her classroom. Because the team was not guided by a shared vision of

learning for all students, collaborative goals, or expectations, this exchange typical of others

observed throughout the study represented a lost opportunity for the whole group.

Discussion and conclusion

While our findings are based on a small-scale qualitative study, we believe they are important in

light of the fact that many schools are investing resources in teacher collaboration and that such

fine-grained illustrations are rare in the research literature. Albeit through negative examples, our

research details what teachers perceive to be critical to making meaningful collegial interaction

happen in the context of structured collaboration, thereby reinforcing the claim that principal leadership practices that flow from the leaders capacity to leverage informal, social processes precede

widely distributed teacher leadership (Kennedy et al., 2011; Marks & Printy, 2003). As illustrated

in our data, some schools are just not ready to rely on teachers in the isolation of their own teams

to bolster widespread improvements in teaching and learning. Even in schools with a reputation for

high performance and collegiality, teachers may need strong direction and support in the early

stages of such improvement efforts because it is unclear why improvement is necessary, where it

should begin, and how its results will benefit teachers and students. As demonstrated by the teachers at Walsh, teams that are asked and able to carry the burden function within a vacuum of

improvement that does little to validate and reinforce their efforts. Moreover, while their isolated

work may support the needs of their students and teachers, it may target vastly different goals,

which does little to promote collective improvement and, in some cases, may obstruct school-wide

efforts to build instructional capacity.

According to our findings, informal leadership practices that target social processes and create

a cultural context for collaboration are particularly important at the high school level, where

instructional programming and practice tend to be ambiguous and are left to the discretion of individual teachers. Indeed, our findings reinforce the power that a shared vision, purpose, and goals

have in creating a context of interdependence and collective responsibility within teams.

Interdependence mediates the uncertainty teachers feel due to their isolated classroom experiences

and the risk associated with exploring problems of practice with colleagues. It also has a motivating effect because teachers no longer view problems of practice as isolated events that reflect their

individual weaknesses; they view them instead as collective problems that deserve collective deliberation. This was certainly true on the Walsh teams, where teachers took the initiative to lead

informally within their teams, thereby establishing a purpose for collaboration and goals to work

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

188

Improving Schools 17(2)

toward. In doing so, they created a context for interdependent work that motivated teachers to collaborate and made common planning time a worthwhile endeavor.

One might argue that data from the Walsh teams prove that it is neither principal leadership,

years together on a team, nor professional experience that matter most to teacher collaboration;

rather, it is teachers capacity to lead informally that matters most. Indeed, previous research suggests that once people understand what their work is and what they are working toward, achieving

the goal becomes more salient than how it was set or who set it (Bandura, 1997). However, our data

suggest that principals cannot assume that such leadership is inherent in teacher teams, nor should

they assume that if there is such leadership, it will result in coordinated, school-wide improvements. Greenpark teams could not bear the burden of informal leadership, and Walsh teams based

their collaborative efforts on the areas of improvement they deemed important, which may or may

not have been a service to the broader school community. Thus, our findings should encourage

principals to take more initiative in establishing a vision, purpose, and goals for their teachers collaborative work (Muijs & Harris, 2006), but they also prompt more questions about how principals

can leverage both their formal and informal authority to do so most effectively (Talbert, 2010).

Our findings illustrate how differentiated, ongoing, job-embedded professional development

that is aligned with an overarching vision for teaching and learning is critical to teachers mastery

of new practices. Even in high-performing contexts, principals cannot assume that the knowledge

and skills needed for improvement already exist and simply need to be mobilized (Elmore, 2004).

As illustrated by our data, teachers on teams from high-performing schools were confronting the

limits of their own knowledge and skill, and being in such a position made them question their

ability to address problems of practice and, therefore, decreased their motivation to even discuss

the problems during structured collaboration. Our findings prompt further questions that complicate how we think about both team-level professional development and team membership. Who is

on the team and what they bring in the way of efficacy, motivation, knowledge, and skill have

implications for how they respond to school-wide or general forms of professional development.

Principals must provide support and guidance to address the unique needs of both the individuals

on a team and the team as a collective. This is important to note because we know that school

improvement is likely to be achieved when individuals feel confident in their own capacity, in the

capacity of their colleagues, and in the capacity of the school to provide adequate professional

development (Mitchell & Sackney, 2000, p. 78).

Also clearly illustrated in our study was teachers desire to receive consistent and meaningful

feedback on their collaborative work, even though it would require the principal to monitor their

process. Teachers in the study were looking for administrators to effectively oversee their collaborative improvement as a way to foster ongoing professional exchange and growth (Talbert, 2010).

From their perspectives, this could be accomplished through differentiated feedback and support,

which in turn would contribute to teacher efficacy and motivation. Moreover, teachers in the study

especially those from Walsh believed that through consistent monitoring administrators could

feed valuable information about teaching and learning gathered at the team level back into the

broader system. By doing so, the principal would play the critical role of knowledge manager and

put the school in the position of establishing what Shulman (2005) refers to as signature pedagogies, which detail the critical aspects of teaching as professional work. While secondary schools

are not known for having tightly prescribed curriculum and instructional practices, establishing a

body of specialized knowledge and agreed-to standards of practice and protocols constrains individual autonomy (Wurtzel, 2006), serves as the foundation of a schools internal accountability

system (Elmore, 2004), and puts it on a sustainable improvement trajectory (Mourshed et al.,

2010). Absent both external pressure to create a sense of urgency and principal leadership to inspire

reflection, the teams would continue to operate in atomistic accountability systems that privilege

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

189

Szczesiul and Huizenga

individual teacher beliefs over shared expectations for teaching and learning, thereby rendering

collective improvement efforts futile (Elmore, 2004). This is an important (and under-recognized)

point because, although suburban schools like Walsh and Greenpark may have a reputation for high

performance, more learning may actually occur in low-income schools where teachers feel responsible for meeting collective expectations for teaching and learning, and for carrying out routines

they developed together to get the work done.

Note

1.

Both Walsh and Greenpark are pseudonyms.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman & Company.

Elmore, R. (2004). School reform from the inside out: Policy, practice, and performance. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard Education Press.

Garet, M. S., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., & Yoon, K. S. (2001). What makes professional

development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educational Research

Journal, 38, 915945.

Geijsel, F. P., Sleegers, P. J., Stoel, R. D., & Krger, M. L. (2009). The effect of teacher psychological

and school organizational and leadership factors on teachers professional learning in Dutch schools.

Elementary School Journal, 109, 406427.

Giles, C. (2007). Building capacity in challenging US schools: An exploration of successful leadership practice in relation to organizational learning. International Studies in Educational Administration, 35(3),

3038.

Goddard, R., Hoy, W., & Hoy, A. (2000). Collective teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure, and impact

on student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 37, 479507.

Goddard, Y., Goddard, R., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2007). A theoretical and empirical investigation of

teacher collaboration for school improvement and student achievement in public elementary schools.

Teachers College Record, 109, 877896.

Horn, I. S., & Little, J. W. (2010). Attending to problems of practice: Routines and resources for professional

learning in teachers workplace interactions. American Educational Research Journal, 47, 181217.

Ingersoll, R. M. (2003). Who controls teachers work?: Power and accountability in Americas schools.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Johnson, S. M. (1990). Teachers at work: Achieving success in our schools. Scranton, PA: Harper Collins

Publishers.

Johnson, S. M., Kraft, M. A., & Papay, J. P. (2012). How context matters in high-need schools: The effects of

teachers working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students achievement. Teachers

College Record, 114(10), 139.

Kellough, R. D., & Kellough, N. G. (2008). Teaching young adolescents: Methods and resources for middle

grades teaching (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall.

Kennedy, A., Deuel, A., Nelson, T. H., & Slavit, D. (2011). Requiring collaboration or distributing leadership? Phi Delta Kappan, 92(8), 2024.

King, M. B., & Bouchard, K. (2011). The capacity to build organizational capacity in schools. Journal of

Educational Administration, 49, 653669.

Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2006). Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: Effects on

students, teachers, and their classroom practices. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17,

201227.

Leithwood, K., Louis, K. S., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). Review of research: How leadership

influences student learning. Paper written for The Wallace Foundation, Center for Applied Research

Educational Improvement, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. Retrieved from http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/school-leadership/key-research/Documents/How-Leadershipinfluences-Student-Learning.pdf

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

190

Improving Schools 17(2)

Levine, T. (2011). Experienced teachers and school reform: Exploring how two different professional communities facilitated and complicated change. Improving Schools, 14, 3047.

Little, J. W. (1982). Norms of collegiality and experimentation: Workplace conditions of school success.

American educational research journal, 19(3), 325340.

Little, J. (1990). The persistence of privacy: Autonomy and initiative in teachers professional relations. The

Teachers College Record, 91(4), 509536.

Little, J. W. (2002). Professional community and the problem of high school reform. International Journal of

Educational Research, 37(8), 693714.

Main, K. (2012). Effective middle school teacher teams: A ternary model of interdependency rather than a

catch phrase. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 18, 7588.

Malen, B., & Rice, J. K. (2004). A framework for assessing the impact of education reforms on school capacity: Insights from studies of high-stakes accountability initiatives. Educational Policy, 18, 631660.

Marks, H., Louis, K. S., & Printy, S. (2000). The capacity for organizational learning: Implications for pedagogical quality and student achievement. Understanding schools as intelligent systems, 239-266.

Marks, H. M., & Printy, S. M. (2003). Principal leadership and school performance: An integration of transformational and instructional leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 39, 370397.

Martinez, J. I., & Jarillo, J. C. (1989). The evolution of research on coordination mechanisms in multinational

corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 20, 489514.

Mertens, S. B., Flowers, N., Anfara Jr, V. A., & Caskey, M. M. (2010). Common planning time. Middle

School Journal, 41(5), 5057.

Mitchell, C., & Sackney, L. (2000). Profound improvement: Building capacity for a learning community.

Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Mourshed, M., Chijioke, C., & Barber, M. (2010). How the worlds most improved schools keep getting better. Report prepared for McKenzie & Company. Retrieved from http://www.teindia.nic.in/Files/Articles/

How-the-Worlds-Most-Improved-School-Systems-Keep-Getting-Better_Download-version_Final.pdf

Muijs, D., & Harris, A. (2006). Teacher led school improvement: Teacher leadership in the UK. Teaching and

Teacher Education, 22(8), 961972.

National Middle School Association. (2010). This we believe: Keys to educating young adolescents.

Westerville, OH: Author.

ODay, J., Goertz, M. E., & Floden, R. E. (1995). Building capacity for education reform. New Brunswick,

NJ: Consortium for Policy Research in Education.

OReilly, C., & Chatman, J. (1996). Culture as social control: Corporations, cults, and commitment. Research

in Organizational Behavior, 18, 157200.

Pascale, R. T. (1990). Managing on the edge. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Robinson, V. (2007). School leadership and student outcomes: Identifying what works and why (Vol. 41).

Winmalee, Victoria, Australia: Australian Council for Educational Leaders.

Rosenholtz, S. J. (1989). Workplace conditions that affect teacher quality and commitment: Implications for

teacher induction programs. The Elementary School Journal, 421439.

Runhaar, P., Sanders, K., & Yang, H. (2010). Stimulating teachers reflection and feedback asking: An interplay of self-efficacy, learning goal orientation, and transformational leadership. Teacher and Teacher

Education, 26, 11541161.

Scribner, J., Sawyer, K., Watson, S., & Myers, V. (2007). Teacher teams and distributed leadership: A study

of group discourse and collaboration. Educational Administration Quarterly, 43, 67100.

Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 5259.

Slavit, D., Kennedy, A., Lean, Z., Nelson, T., & Deuel, A. (2011). Support for professional collaboration in

middle school mathematics: A complex web. Teacher Education Quarterly, 38(3), 113-131.

Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities:

A review of the literature. Journal of educational change, 7(4), 221258.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oakes, CA: SAGE.

Talbert, J. (2010). Professional learning communities at the crossroads: How systems hinder or engender

change. In A. Lieberman (Ed.), International handbook of educational change. (pp. 555-571) Dordrecht,

The Netherlands: Springer.

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

191

Szczesiul and Huizenga

Thoonen, E., Sleegers, P., Oort, F., Peetsma, T., & Geijsel, F. (2011). How to improve teaching practices: The

role of teacher motivation, organizational factors, and leadership practices. Educational Administration

Quarterly, 47, 496536.

Tschannen-Moran, M. (2004). Trust matters. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and

Teacher Education, 17, 783805.

Wahlstrom, K. L., & Louis K. S. (2008). How teachers experience principal leadership: The roles of professional community, trust, efficacy, and shared responsibility. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44,

458495.

Wurtzel, J. (2006). Transforming high school teaching and learning: A district-wide design. Report prepared for the Aspen Institute. Retrieved from Institute. http://www.schoolinfosystem.org/archives/

EducationTransforming_High_School_Teaching_and_Learning_A_District_wide_Design.pdf

Youngs, P., & King, M. B. (2002). Principal leadership for professional development to build school capacity.

Educational Administration Quarterly, 38(5), 643-670.

Downloaded from imp.sagepub.com at Universiti Utara Malaysia on March 25, 2016

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Cause and EffectDocument5 pagesCause and EffectTane MB100% (2)

- Instructional Supervisory Plan 2022Document6 pagesInstructional Supervisory Plan 2022Nina OcliasaNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesLesson PlanThiruchelvylaxmi100% (1)

- Detailed Lesson Plan School Grade Level Teacher Learning Areas Teaching Dates and Time QuarterDocument5 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan School Grade Level Teacher Learning Areas Teaching Dates and Time QuarterKhesler RamosNo ratings yet

- Phil IRI Manual Oral Reading PDFDocument22 pagesPhil IRI Manual Oral Reading PDFMaila RosalesNo ratings yet

- 4th Grade-EnglishDocument4 pages4th Grade-Englishapi-32541207No ratings yet

- Role of ICT in Higher EducationDocument5 pagesRole of ICT in Higher EducationregalNo ratings yet

- Case 1 XeroxDocument4 pagesCase 1 Xeroxalanz123No ratings yet

- I I I I I + I: ElektrikDocument2 pagesI I I I I + I: Elektrikalanz123No ratings yet

- Mfrs 121Document2 pagesMfrs 121alanz123No ratings yet

- Organizational Identity and Its Implication On Organization DevelopmentDocument8 pagesOrganizational Identity and Its Implication On Organization Developmentalanz123No ratings yet

- Mrfs 118Document2 pagesMrfs 118alanz123No ratings yet

- MFRS102 - Inventories DefinitionsDocument8 pagesMFRS102 - Inventories Definitionsalanz123No ratings yet

- Education Reform The Past and PresentDocument17 pagesEducation Reform The Past and Presentalanz123100% (1)

- N 180 Min 294 Max 3, 292: Step 1Document2 pagesN 180 Min 294 Max 3, 292: Step 1alanz123No ratings yet

- CHEN SOON LEE VDocument16 pagesCHEN SOON LEE Valanz123No ratings yet

- Educational Management Administration & Leadership-2014-Minckler-School Leadership ThatDocument23 pagesEducational Management Administration & Leadership-2014-Minckler-School Leadership Thatalanz123No ratings yet

- A Discursive Approach To Leadership: Doing Assessments and Managing Organizational MeaningsDocument21 pagesA Discursive Approach To Leadership: Doing Assessments and Managing Organizational Meaningsalanz123No ratings yet

- 2015 XXXDocument20 pages2015 XXXalanz123No ratings yet

- Specialty: Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis NumberDocument6 pagesSpecialty: Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis NumberalpNo ratings yet

- English As A Medium of Instruction (EMI) Module 1: Task 2 - Complete 5 Readings Reading 1.1: Common Models For EMI InstructionDocument2 pagesEnglish As A Medium of Instruction (EMI) Module 1: Task 2 - Complete 5 Readings Reading 1.1: Common Models For EMI InstructionEucarlos Martins100% (1)

- Condensed ResumeDocument2 pagesCondensed Resumeapi-282038894No ratings yet

- French Second Language Grade 8 - Francophone Culture - 16 Days - 60 Minute Lessons Unit OverviewDocument25 pagesFrench Second Language Grade 8 - Francophone Culture - 16 Days - 60 Minute Lessons Unit Overviewapi-300964625No ratings yet

- Philosophy of EducationDocument3 pagesPhilosophy of Educationapi-260334489No ratings yet

- Introducing Teaching STEAM As An Educational Framework in KoreaDocument29 pagesIntroducing Teaching STEAM As An Educational Framework in KoreaRacu AnastasiaNo ratings yet

- M4AL-IIIe-13-w5 - d4Document7 pagesM4AL-IIIe-13-w5 - d4Rhealyn Kaamiño100% (1)

- Year 4 Cefr SK Week 2Document23 pagesYear 4 Cefr SK Week 2Hairmanb BustNo ratings yet

- Group-6 TGDocument3 pagesGroup-6 TGCristy GallardoNo ratings yet

- Refrences. BanbeDocument10 pagesRefrences. Banbeoluwatoworship001No ratings yet

- Students and Teachers Perspective of The Importance of Arts in Steam Education in VietnamDocument6 pagesStudents and Teachers Perspective of The Importance of Arts in Steam Education in VietnamErika NguyenNo ratings yet

- HISD Strategic Plan WorkshopDocument79 pagesHISD Strategic Plan WorkshopHouston ChronicleNo ratings yet

- Differentiated L NewDocument60 pagesDifferentiated L NewAbdul Nafiu YussifNo ratings yet

- I e Prating ScalesDocument18 pagesI e Prating ScalesAndi Agung RiatmojoNo ratings yet

- Legal Latin TermsDocument100 pagesLegal Latin TermsEdwino Nudo Barbosa Jr.No ratings yet

- Critical MulticulturalismDocument14 pagesCritical MulticulturalismsamNo ratings yet

- UNIT 2 School As An Agent of Social ChangeDocument54 pagesUNIT 2 School As An Agent of Social ChangeMariane EsporlasNo ratings yet

- Resume 2020Document3 pagesResume 2020api-427644091No ratings yet

- Presentation On Teaching Methodology in ChemistryDocument40 pagesPresentation On Teaching Methodology in ChemistrySubhav AdhikariNo ratings yet

- Failure Is Not An Option Ea7720Document14 pagesFailure Is Not An Option Ea7720api-515736506No ratings yet

- Local Media6171616519365341648Document4 pagesLocal Media6171616519365341648Arjun Aseo Youtube ChannelNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan (KSSR) : Set Induction (5 Minutes)Document3 pagesDaily Lesson Plan (KSSR) : Set Induction (5 Minutes)unknown lolNo ratings yet

- Discuss Both View EssayDocument4 pagesDiscuss Both View EssayUyen VuNo ratings yet