Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents PDF

Uploaded by

lauravbleedioteOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents PDF

Uploaded by

lauravbleedioteCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Adolescent

Research

http://jar.sagepub.com/

Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents

May Lau, Christine Markham, Hua Lin, Glenn Flores and Mariam R. Chacko

Journal of Adolescent Research 2009 24: 91

DOI: 10.1177/0743558408328439

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://jar.sagepub.com/content/24/1/91

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Journal of Adolescent Research can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://jar.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://jar.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://jar.sagepub.com/content/24/1/91.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Dec 23, 2008

What is This?

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

Dating and Sexual

Attitudes in Asian-American

Adolescents

Journal of Adolescent

Research

Volume 24 Number 1

January 2009 91-113

2009 Sage Publications

10.1177/0743558408328439

http://jar.sagepub.com

hosted at

http://online.sagepub.com

May Lau, MD, MPH

UT Southwestern Medical Center and Childrens

Medical Center, Dallas, TX

Christine Markham, PhD

University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, TX

Hua Lin, PhD

UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX

Glenn Flores, MD

UT Southwestern Medical Center and Childrens

Medical Center, Dallas, TX

Mariam R. Chacko, MD

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Dating behaviors and sexual attitudes of Asian-American youth were examined

in a cross-sectional, mixed-methods study in the context of adherence to Asian

values, measured by the Asian Values Scale (AVS). In all, 31 Asian-American

adolescents (age 14-18 years old) from a Houston community center were

interviewed regarding dating behaviors and sexual attitudes. Almost threefourth of adolescents dated without parental knowledge. Compared with

adolescents with the lowest AVS scores, those with the highest AVS scores were

significantly more likely to date without parental knowledge and date longer

before sex. Many adolescents proceeded directly to single, steady, relationships.

Parents permitted dating, as long as grades were maintained. Asian-American

adolescents should be questioned about secret dating, sexual activity, and

participation in other high-risk activities.

Keywords:

dating; sexual behavior; Asian-Americans; adolescent; acculturation; sexual attitudes

Dating and Sexual Attitudes

Dating, an important element of normal adolescent development in

the United States, is generally initiated between 13 and 15 years of age.

Approximately 90% of adolescents have had dating experience by age 17

91

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

92

Journal of Adolescent Research

(Longmore, Manning, & Giordano, 2001; Michael & Bickert, 2001;

Thornton, 1990). Dating serves many different roles, including recreation,

companionship, elevating social status, improving relationship skills, exploring sexuality, and courtship (McCabe, 1984; McDaniel, 1969; Skipper &

Nass, 1966). Negative consequences associated with dating include depressive symptoms, poor psychosocial functioning, and disordered eating habits

in girls, poor academic achievement, and early initiation of sexual activity

(Cauffman & Steinberg, 1996; Cooksey, Mott, & Neubauer, 2002; Davies &

Windle, 2000; Michael & Bickert, 2001; Quatman, Sampson, Robinson, &

Watson, 2001; Zimmer-Gembeck, Siebenbruner, & Collins, 2001). Dating is

the strongest predictor of initiating sexual activity (Meier, 2003). Studies of

adolescents with dating experience reveal that 25%-50% report a history of

sexual activity (Cooksey et al., 2002; Longmore et al., 2001). The examination of dating behaviors as a precursor to sexual activity is important in

understanding datings role in sexual initiation.

While dating is one contributor to sexual initiation among adolescents,

sexual attitudes are another, with early onset of dating related to permissive

sexual attitudes (Feldman, Turner, & Araujo, 1999; Meier, 2003; Thornton,

1990). Studies have demonstrated that boys possess more permissive sexual

attitudes than girls (Feldman et al., 1999; Meier, 2003). One study reported

that boys were more likely than girls to believe physical intimacy could

occur earlier in the dating process and that this intimacy was unrelated to

the seriousness of the relationship (Knox & Wilson, 1981; Roche, 1986).

Asians, Dating, and Sexual Attitudes

For Asian adolescent immigrants from countries such as China, Taiwan,

and Vietnam, the seemingly normal peer behavior view of dating in the

Authors Note: This research project was conducted in part while Dr. Lau was a fellow in the

Section of Adolescent & Sports Medicine and the Leadership Education in Adolescent Health

(LEAH) Program at Baylor College of Medicine. It partially fulfilled Dr. Laus masters in

public health requirements at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. This

study was funded in part by the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, School

of Public Health Student Research Award, UT Southwestern Department of Pediatrics, and the

Maternal and Child Health LEAH training grant 6T71 MC00011 and was presented in part as

a poster at the 2005 Society of Adolescent Medicine annual meeting in Los Angeles. The

authors thank the Chinese Community Center for the use of its facilities. Most of all, the

authors thank the participating Asian-American adolescents for their honesty. Correspondence

concerning this article should be addressed to May Lau, Division of General Pediatrics,

Department of Pediatrics, UT Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard,

Dallas, TX 75390-9063; e-mail: may.lau@utsouthwestern.edu.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

Lau et al. / Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents

93

U.S. tends to contradict traditional Asian cultural mors, which view adolescents developing interest in the opposite sex as inappropriate (Tang &

Zuo, 2000). Traditionally, Asian parents on average believe that dating

leads to marriage, and it is thus not generally condoned (Kibria, 1993; Tang

& Zuo, 2000). A childs main responsibility often is viewed as excelling in

academics, with dating viewed as a distraction (Kim & Ward, 2007; Louie,

2004; Nguyen, 1998; Sung, 1985; Yu, 2007). Many Asian adolescents

agree. One study among Hong Kong Chinese adolescents reported that

youth placed greater value on school grades, future education, and career

than on dating and sex (Violato & Kwok, 1995). Taiwanese and Japanese

adolescents spend less time dating, compared to their U.S. peers (Fuligni &

Stevenson, 1995). When dating does occur in Asian youth, the age of onset

usually occurs later. Only one-third of college students in China had dated,

versus two-thirds of college students in the United States, with onset of dating occurring at a much earlier age in the United States (Tang & Zuo,

2000).

Traditional Asian culture emphasizes chastity, with procreation the only

goal of sexual activity (Brotto, Chik, Ryder, Gorzalka, & Seal, 2005;

Nguyen, 1998). Therefore, it is to be expected that Asians generally possess

more conservative sexual attitudes than peers of other races/ethnicities. In

Hong Kong, Chinese medical students have more conservative sexual attitudes compared to their U.S. peers (Chan, 1990). Gender differences are

also apparent in sexual attitudes, with Asian boys generally having more

liberal sexual attitudes than Asian girls (Chang, Tsang, Lin, & Lui, 1997;

Ip, Chau, Chang, & Lui, 2001).

Acculturation and Adherence to Asian Values

Acculturation is the process by which a racial/ethnic minority individuals attitudes and behaviors are affected over time by the culture of a host

country (Abe-Kim, Okazaki, & Goto, 2001). The current dominant paradigm regarding acculturation is the bi-dimensional model, which maintains

that while an individual sheds the behaviors, values, and practices of their

racial/ethnic culture, acquisition of the equivalent from the host culture also

occurs (Chun, Organista, & Marin, 2003). Acculturation is often measured

by length of residency in host country, primary language spoken at home,

or country of origin (Chun et al., 2003; Felix-Ortiz, Newcomb, & Myers,

1994). Retention of traditional values and behaviors are more uncommon

ways to measure acculturation.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

94

Journal of Adolescent Research

Many Asian-American parents expect their children to uphold traditional Asian values, such as elder respect, chastity, obedience, and family

over the individual (Chun et al., 2003). Generally, Western traits such as

individuality, independence, or freedom are not condoned (Nguyen, 1998;

Sung, 1985). As a result, many Asian-American adolescents spend time

navigating between two different, and possibly opposing, cultures (Chun

et al., 2003; Yu, 2007). These adolescents attempt to incorporate values

from two different cultures to maintain their ethnic identity while also trying to create their own identity and to fit in with peers (Phinney, 1989).

Research on cultural values demonstrates that Asian-American adolescents

generally retain aspects of their traditional culture. Asian-American adolescents

place greater emphasis on elder respect and obedience compared to their

European peers (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999). In a cross-cultural study by

Feldman, Mont-Reynaud, and Rosenthal (1992), White youth, first- and secondgeneration Chinese youth in the U.S. and in Australia, and their peers in Hong

Kong were asked about values in five different areas: well-socialized behavior;

traditional values; universal prosocial (attitudes toward equality and peace);

outward success; and individualism. The cultural environment of the U.S. and

Australia had an influence on the Chinese youth, because these first- and

second-generation Chinese placed less importance on Asian values and

more value on outward success (Feldman, Mont-Reynaud, & Rosenthal,

1992). However, the first- and second-generation Chinese youth still valued

family on average more than their Western counterparts.

Acculturation, Dating, and Sexual Attitudes

Adherence to Asian values may explain behavioral differences that exist

between Asian-Americans and their peers of different race/ethnicities. For

example, Asian-American adolescents engage in dating behaviors at lower

rates and spend less time dating as compared to peers of other races/

ethnicities (Chen & Stevenson, 1995; Reglin & Adams, 1990). AsianAmerican adolescents sexual attitudes generally become less conservative

with increasing acculturation, as measured by country of origin or acculturation scale (Brotto et al., 2005; Chen & Yang, 1986; Huang & Uba, 1992;

Yu, 2007). When compared to their U.S. peers of different races/ethnicities,

Asian-American college students had more restricted sexual attitudes and

initiate physical intimacy later, presumably due to their normative cultural

values (Feldman et al., 1999). Research on the influence of adherence to

Asian values on dating and sexual attitudes is virtually nonexistent.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

Lau et al. / Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents

95

The purpose of this exploratory, mixed-methods study was to examine

the dating behaviors and sexual attitudes of Asian-American adolescents

and the impact of Asian cultural values on dating and sexual attitudes in

Asian-American adolescents.

Methods

Study Setting

This study was conducted at a Chinese community center in a southwestern city of the United States where Asian-Americans comprise 5% of

the population. The center serves many races/ethnicities including Whites,

African-Americans, and other Asian ethnicities.

Participants and Study Protocol

A convenience sample of youths aged 14 to 18 years old was recruited via

posters and word of mouth at the centers after-school volunteer program and

Chinese-language school for high school students. It was assumed that high

school youth would be able to comprehend the Asian Values Scale (AVS) as

an eighth-grade reading level was needed to complete it (Kim, Atkinson, &

Yang, 1999). Enrollment in a class with English as a second language and

inability to read at an eighth-grade level were reasons for exclusion from the

study, because the AVS was not translated into Chinese. Parental consent and

subject assent were obtained from all participants.

The study was conducted in two parts. Participants completed an enrollment survey in English lasting approximately 20 minutes and consisting of

open-ended and multiple-choice questions. The enrollment survey was

comprised of sociodemographic questions including age, date of birth,

grade in school, and the AVS. Participants were then scheduled at a later

date for a confidential, tape-recorded individual interview to discuss dating

and sexual attitudes. Depending on responses to the dating questions, participants were asked up to 15 questions regarding their dating behaviors.

The sexual attitudes section consisted of six questions. All dating and

sexual attitudes questions developed for the individual interviews were

reviewed by researchers who had experience working with adolescents.

Questions in the dating section were derived from dating research by

Montgomery and Sorell (1998). The dating section included questions

about the participants definition of dating, age of first date, and parental

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

96

Journal of Adolescent Research

permission to date. A sample question was: So a lot of teens are interested

in dating. Are you allowed to go on dates? Sexual attitudes questions were

based on the work of Hansen, Paskett, and Carter in their development of

the Adolescent Sexuality Activity Index (Hansen, Paskett, & Carter, 1999).

The sexual attitudes section included questions about personal timelines for

physical intimacy in relation to number of dates. A sample question was:

How many dates would you have to go out with someone to kiss him/her?

Each study participant was interviewed for approximately 20 minutes in a

quiet room specifically designated for the study at the center. The interviewer provided probes so that participants could clarify and expand

answers when needed. Dating and sexual attitudes topics that were brought

up in earlier interviews were included in subsequent interviews of the

remaining adolescents. All interviews were conducted by the first author to

ensure consistency. Participants were compensated for their time with two

movie tickets. This study was approved by the Chinese community center,

the Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine, and the

Committee for Protection of Human Subjects of the University of Texas

Health Science Center HoustonSchool of Public Health.

Measures

The AVS uses a modified Likert-type scale in which 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = moderately disagree, 3 = mildly disagree, 4 = neither agree nor

disagree, 5 = mildly agree, 6 = moderately agree, 7 = strongly agree. Scores

were based on responses to 36 statements written at a middle school reading level (Kim et al., 1999). Asians from different Asian countries prescribe

to and commonly define the six Asian cultural values themes examined in

the AVS (Kim, Yang, Atkinson, Wolfe, & Hong, 2001). The six Asian cultural values themes explored were:

1. Collectivism, which emphasizes the needs of the group over the individual

and that an individuals success is a reflection of the familys success;

2. Conformity to norms, which focuses on the importance of adherence to

familial and societal expectations and not disgracing the family;

3. Emotional self-control, which deals with the ability to not show ones

emotions and to express parental love;

4. Family recognition through achievement, which stresses academic

achievement;

5. Filial piety, which describes respecting parents and caring for them when

they become older;

6. Humility, which addresses the importance of being humble and modesty.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

Lau et al. / Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents

97

Each statement in the scale reflected one of the above themes. Positively

and negatively worded items were included, with the negative items being

reverse scored. For a positively worded statement, such as One should be

humble and modest, a subjects actual numerical rating of the statement

was used to calculate the total score. For a negatively worded statement, such

as, Educational failure does not bring shame to the family, a subjects

numerical rating of 1 was reverse scored to 7. The AVS also has been used in

several studies to assess values in immigrant, first-, and second-generation

Asian-American college and high school students (Hynie, Lalonde, & Lee,

2006; Kim et al., 2001; Kim & Omizo, 2003).

Using the AVS as a continuous scale, scores for level of adherence to

Asian values can range from 36 to 252; those with lower scores demonstrate a lower adherence to Asian values, whereas those with higher scores

demonstrate a higher adherence (B. Kim, personal communication,

December 9, 2004). Internal consistency of the AVS was determined to be

.81, as measured in Asian-American college students 18 to 38 years old

with a mean age of 20.4 years (Kim et al., 1999). Cronbachs alpha and

testretest reliability for this AVS range from .81 to .83 in Asian-American

college students (Kim et al., 1999). Cronbachs alpha for the AVS for our

study population was .79.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize sociodemographic data,

including age, gender, and race/ethnicity. All audiotapes from the individual

interviews were transcribed verbatim. The first author coded and analyzed the

transcripts for content and recurring themes regarding dating behaviors and

sexual attitudes. These themes were constantly compared to refine them

(Glaser, 1965). The codes from one transcript were compared to codes of other

transcripts to identify similarities and differences in relation to gender and

level of adherence to Asian values. The second author reviewed a 20% sample

of the transcripts to provide consistency in generation of codes and themes by

the first author and to make recommendations for any necessary amendments.

Once these themes were identified, all transcripts were reviewed to detect

presence or absence of the various themes. Frequencies of themes were calculated according to gender. Examination of themes by level of acculturation

was conducted by comparing transcripts sequentially from lowest to highest

AVS scores (i.e., from low to high adherence to Asian values), both for the

overall sample and separately by gender. Sample quotes were selected for each

theme that reflected the range of responses.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

98

Journal of Adolescent Research

Due to the small number of subjects and the unknown distributions of

many variables, the KruskalWallis test was used to analyze the relationship between the continuous variable (AVS score) and categorical variables

(dating behaviors and sexual attitudes). Clustering of the AVS scores and

the small sample size were the basis for examining the extreme categories

of data to determine if a relationship existed between AVS scores, dating,

and sexual attitudes. Linear correlation coefficients were used to determine

if a relationship existed between AVS scores and sexual attitudes. The chisquare test was used to compare gender differences.

Results

Participant Recruitment

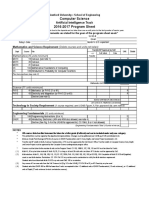

Fifty-two youth were interested in participating in the study, and 31

youths completed the entire study (Figure 1). The most common reason for

non-participation was the time commitment and/or lack of interest in discussing dating and sexual attitudes. Other reasons included not being

allowed to date, and not being interested in participating after further study

details were revealed. Six youths who finished the enrollment survey did

not complete the confidential interview because of scheduling difficulties

and/or parents withdrawing consent to participate in the study.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

The median age of the participants was 17 years; 58% were male (Table 1).

Most youth were of Chinese descent, either in the 11th or 12th grade, born

in the U.S. and the youngest in the family. These adolescents mostly

befriended other Asian-Americans.

Dating Behaviors of Participants

Most participants had dated, and the mean age of dating initiation was

13.9 years (Table 2). Almost two thirds of the group had parental permission to date including two thirds of boys and more than half of girls. More

than two thirds (70%) dated without parental knowledge. Among adolescents without parental dating permission, 92% dated without parental

knowledge. Among adolescents with explicit parental dating permission,

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

Lau et al. / Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents

99

Figure 1

Flow DiagramSampling Frame and Number of

Asian-American Youth Dating With Parental Permission

and/or Parental Knowledge

52 youths

approached

21 did not

participate/

complete

study

31 completed

study

15 did not

like study

topic or time

commitment

19 had

permission

to date

10 dated

without

parental

knowledge

6 did not

complete

confidential

interview

12 did not

have

permission

to date

9 dated with

parental

knowledge

11 dated

without

parental

knowledge

1 youth did not

date without

parental

knowledge

more than half dated without parental knowledge. There was no significant

difference in the proportion of adolescents with and without dating permission who were currently in a relationship. Dating partners were met via

school, extracurricular activities, or friends. The primary method used to

invite someone on a date was in person, although about one quarter used the

phone; notes and instant messaging were less common methods. There was

a nonstatistically significant trend toward boys being more likely to be the

main inviters for dates (p = .052). No significant gender differences existed

in any other dating behavior.

AVS scores for the study population ranged from 109 to 206; the mean

score was 155.1 ( SD 20.7), and the median score, 152. For boys, the mean

score was 152.7 ( SD 17.6) with a range of 109 to 176 and a median score

of 154.5. For girls, the mean score was 158.3 ( SD 24.7) with a range of

127 to 206 and a median of 151. No significant gender difference in AVS

scores were noted by relationship status, age of dating onset, or parental

knowledge of dating category.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

100

Journal of Adolescent Research

Table 1

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Study Adolescents (n = 31)

Characteristic

Median or %

Age

Gender

Male

Female

Race/ethnicity

Chinese

Taiwanese

Vietnamese

Biracial

Grade

9th

10th

11th

12th

13th

Place of birth

Texas

In the U.S. but outside of Texas

China

Birth order in family

Only

Eldest

Youngest

Most friends race/ethnicity

Asian

White

African American

Mixed

17.0

58.0%

41.9%

67.7%

22.6%

6.5%

3.2%

12.9%

19.4%

25.8%

29.0%

12.9%

77.4%

19.4%

3.2%

9.7%

32.3%

58.1%

83.9%

3.2%

3.2%

6.5%

AVS Scores and Dating/Sexual Attitudes

Analysis of the entire study population demonstrated that no correlation

existed between AVS scores and dating behaviors or sexual attitudes.

Additional statistical analysis was performed due to clustering of the AVS

scores at the extremes. These additional analyses revealed that adolescents

with the highest AVS scores were significantly more likely to date without

parental knowledge than those with the lowest scores (p < .05; Table 3).

These adolescents were more likely to meet their partners through friends and

less likely to meet their partners through extracurricular activities (p < .05),

and they were more likely to invite someone on a date via phone (p < .05).

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

Lau et al. / Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents

101

Table 2

Dating Behavior Characteristics of Study Adolescents (n = 31)a

Characteristic

Has dating experience

Has parental dating permission

Dates without parental knowledge

With parental dating permission

Without parental dating permission

Mean age of dating initiation, median

Mean number of lifetime dating partners, median

Currently in a relationship

With parental dating permission

Without parental dating permission

Met partners through

Friends

School

Extracurricular activities

Asked someone on a date

Method of date invitation

Person

Phone

Notes

Instant message

Partner race/ethnicity

Asian

Hispanic

African

White

a

Total

Male

Female

93.5%

61.3%

70.0%

52.4%

47.6%

13.9 (13)

3.7 (3)

41.9%

42.1%

41.7%

88.9%

66.7%

70.6%

63.6%

83.3%

13.9 (13)

4.0 (2.5)

38.9%

41.7%

33.3%

100%

53.9%

69.2%

42.9%

100%

13.9 (14)

3.3 (3)

46.2%

42.9%

50.0%

27.6%

37.8%

34.5%

44.8%

16.7%

33.3%

38.9%

72.2%

38.5%

38.5%

23.1%

0%

53.6%

28.6%

7.1%

10.7%

38.9%

33.3%

0%

11.1%

61.5%

15.4%

15.4%

7.7%

86.2%

3.4%

3.4%

6.9%

77.8%

5.6%

0%

5.6%

84.6%

0%

7.7%

7.7%

There were no significant differences in dating behaviors between boys and girls.

Adolescents with the highest AVS scores were significantly more likely

to state sexual intercourse was appropriate after a longer period of dating

(p < .05); this relationship was not seen with other physically intimate behaviors (holding hands, kissing, cuddling, necking, and touching underneath

clothing). Almost half of adolescents believed sexual intercourse could take

place after dating for one year or less.

Qualitative Results

Dating definitions. Several terms were used to define different dating

stages. Some terms had only one definition, whereas others had multiple

definitions. Talking to was used to describe the period of time to become

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

102

Journal of Adolescent Research

Table 3

Dating Behavior Characteristics of Study Adolescents

With the Highest and Lowest AVS Scores

Characteristic

Dating without parental knowledge

Without parental dating permission

Met partner through

Friends

School

Extracurricular activities

Method of date invitation

Phone

Person

Notes

Instant message

Have dating experience

Have parental dating permission

Average age of dating initiation

Average number of lifetime dating partners

Currently in a relationship

With parental dating permission

Without parental dating permission

Partner ethnicity

Asian

Hispanic

African American

White

a

Highest AVS

Scorers

(n = 6)

Lowest AVS

Scorers

(n = 6)

pa

100%

16.7%

50%

33.3%

<.05

ns

83.3%

16.7%

0%

0%

33.3%

66.7%

<.01

ns

.01

50%

33.3%

16.7%

0%

100%

16.7%

14.5 (1.38)

3.83 (2.86)

33.3%

0%

40%

0%

66.7%

0%

0%

83.3%

66.7%

13.8 (1.30)

3.83 (3.19)

66.7%

50%

100%

<.05

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

ns

66.7%

0%

0%

33.3%

83.3%

0%

0%

0.0%

ns

ns

ns

ns

For comparison between adolescents with the highest and lowest AVS scores.

acquainted with someone of interest and was defined in this manner by a

16-year-old girl:

Because, when you are friends and then you go to talking, and that is like an

extended period of time, and its just that you acknowledge that you two like

each other, but you dont want to do anything, yet, I guess, be more committed to each other. So you just talk to each other every day, and its a little

more intimate than being friends, and then after whatever given amount of

time, whenever you guys are comfortable with each other, then you guys just

go out.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

Lau et al. / Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents

103

A 16-year-old boy described talking to in this fashion:

Because talking is like the process of just before, where you just get to know

each other better, so you dont just leap into something that you all are just

not ready for. So you get to know them better, so yall can make the decision,

do yall want to go out or you dont want to go out.

Holla at or Holler at were terms mainly used by boys and had a several definitions. For one 17-year-old boy, holla at meant taking her out and

talk to her on the phone, probably 7, 8 hours a day until the next day. Another

16-year-old boy described holla at as, I think you want to go out with the

girl, no talking, just you want to go with a girl. An additional definition by

another 16-year-old boy was: It is like you want to holler at that girl, you

want to get her to get interested in you. According to a 14-year-old girl, it

had nothing to do with dating, but rather Ill holler at you later, meant

Ill call you later and Ill talk to you later. Hooking up was a term used

to describe connecting two people together, the casual or serious part of a dating relationship or sexual intercourse. Seeing each other referred to the

process of getting to know someone by going out on dates. Dating covered

the spectrum of a relationship, from the start of a dating relationship to someone being involved in a serious relationship. Going out described an exclusive relationship in which labels such as boyfriend and girlfriend were used.

Interestingly, this term was also used to describe a relationship once the individuals involved had set up an actual date. A recurrent theme articulated by

Asian-American teens was that they did not date like their peers of other

races/ethnicities but started by talking to someone and then proceeded

directly to going out. Intermediate stages were skipped, such as going on

dates to determine whether to go out with each other exclusively. Once asked

out on a date, several girls considered themselves automatically in an exclusive relationship. A 16-year-old girl explained:

I dont think Asian people have a dating. We, like Ive never dated. Its

more like you have this period where both of you know it and you like each

other and I guess talking and then theres just going out. But thats not dating. Its just, oh, you guys are together.

For dating, you know that you guys like each other and thats why you go

out on a date so you get to know each other more, but with us, its like . . .

because some of us have more strict parents, its just that you talk to each

other, like talking, and you just get to know them better, but you dont go out

to do that. After whatever period of time you guys want to be boyfriend and

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

104

Journal of Adolescent Research

girlfriend, then you are boyfriend and girlfriend. So theres no talking, dating,

then boyfriend and girlfriend. Its just talking, then boyfriend and girlfriend.

A 17-year-old boy agreed: Asian people think the only way to be going

out on a date with a person is if they have to actually be boyfriend and girlfriend before you can go out on a date.

Dating and education. The relationship between dating and education

was not a focus of this study, but was a recurring theme. Many adolescents

reported that their parents emphasized education over dating. Some participants were allowed to date as long as their grades were maintained. A 14year-old girl described her parents view on dating: Well, my parents have

never really talked about it, but basically the rule is that I technically can,

to a point, until my grades get in the way. A 17-year-old boy stated: I

dont think they really cared, as long as I did my schoolwork.

One 18-year-old girl stated that her parents did not know the seriousness

of her relationship with her boyfriend because she felt her parents would

blame him if she did poorly in school:

They know I have a guy that I spend a lot of time with, but I dont think they

really know how serious it is, because I really dont want them to know,

because if something ever happened with me in school, if I failed a class, I

know that they would blame him, even though it would probably be my fault

because he is really supportive and its not like I am always with him, but

they would think that. They would think that he is a bad influence on me.

A 16-year-old boy remarked:

Well if Im too involved with a girl, I would probably think of her during

class and I wouldnt pay attention. I would get off the subject and my schoolwork would get a lot worse. It has happened before.

Dating and parental permission. Many adolescents went out on dates

even though they did not have explicit parental permission. Discussion

regarding dating rarely occurred between parents and adolescents. For one

16-year-old boy who did not have parental permission to date but dated

without parental knowledge, the ground rules for his friendships with girls

were set by his parents. His parents told him:

You are allowed to have friends that are girls, but you are not allowed to go

out until you graduate college or until you are from 25 to 30ish. You cannot

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

Lau et al. / Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents

105

talk to any girls. I mean you can talk to girls, they can be your friends, but

they can never be more than that.

An 18-year-old boy described confusion about parental permission to date:

I am not sure anymore because its like, at first, it was like, you know, my

parents were like, not until you get into college or whatever, but then like I

had girlfriends in high school and it became pretty obvious and they didnt

say anything, so I dont know.

Some adolescents did go on dates, although their parents may not have

acknowledged it. One 19-year-old girl stated: Well, according to them, it

was not dating. It was me hanging out with friends. I mean, they met the

people and they were just, Okay, go have fun with your friend.

Adolescents with and without parental permission to date dated without

parental knowledge. These adolescents told their parents that they were going

out with friends. One 16-year-old girl said: but for Asians, its harder, because

your parents never know about it. And you say youre going out with friends,

but instead you are going out with a guy. These friends usually knew the adolescent was on a date. For both genders, telling parents that they were out with

friends permitted them to stay out later. According to one 17-year-old boy:

Well, you use friends as an excuse. You say, Oh, my friends birthday is

today. When your parents know that its his friends birthday, hell probably

stay out a little bit late. Hell let us know. And then you use your friends and

tell them just cover for me and I got your back the next time you need me, so

its a mutual helping I guess.

An 18-year-old girl stated her mother would be more concerned if she

was out late with a guy instead of her friends:

If I was with my friends, like my good female friends, like 12 or something,

because we were just like, Oh, we were just watching a movie. Its no big

deal. But if I say, Oh I was out with him until 12 . . . she would be angry.

She would yell at me.

Reasons for dating. The reasons for dating varied. Dating was a means

of entertainment for many Asian adolescents and provided experience and

preparation for a future serious relationship. One 16-year-old girl declared:

Well, in middle school or high school it is practice or for fun. But I guess

in college and beyond you are doing it to find true love.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

106

Journal of Adolescent Research

Many adolescents wanted to be similar to their peers who were involved

in relationships. A 15-year-old girl stated she wanted to date because its

more like a everybody else does it kind of thing. As one 17-year-old boy

clarified:

I am raised in a Chinese family in which people believe that you are supposed

to have a career at first before you start dating, but when you are raised here after

like, its kind of hard not to do the things that kids here do like date. My parents

think that I should wait until I get a good education and then start dating.

A 15-year-old girl agreed:

I want to date because I think it goes along with peer pressure, like everyone

has someone and when you dont have someone, you just would like someone and then the whole purpose of dating would be to find that someone.

Besides being able to have a confidant, a few individuals expressed dating as a means to boost ones reputation. A 17-year-old boy explained:

Lets say I date a really beautiful girl and I walk around and another boy

comes around and says, Is that your girlfriend? Ill be, Yeah, thats my girlfriend. It makes you feel kind of like, Yeah, Im the man and I did that.

However, female adolescents were also not immune to the effect of dating on their reputation. A 17-year-old girl explained her reason for dating:

Just always having someone to go with. Kind of like a show-off thing. Like

at school, all the guys at my school are really ugly, so we usually date outside of school and then its kind of like my boyfriend is better than yours or

my boyfriend has a nicer car or something.

Timelines for Intimacy

As the level of physical intimacy increased in a relationship, the period

of time in a dating relationship before engaging in that behavior generally

increased. For holding hands with a romantic interest, the appropriate timeline ranged from prior to the start of dating to one year. Kissing, cuddling,

and necking (kissing someone for an extended period of time on the face

and neck) timelines extended from prior to the start of dating to one year.

For more intimate physical behaviors, such as touching and sexual activity,

the timelines spanned from prior to the start of dating to marriage. One

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

Lau et al. / Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents

107

adolescent noted that this concept of physical intimacy prior to a dating

relationship is reinforced by peer behavior: Because I just see it, like

friends just do it, because they want to and they are really close friends, but

they are not really dating or something.

One adolescent stated that she had changed her perspective after engaging in sexual intercourse:

Before, I never thought that it was a big deal, but now I think you should

really wait until you are married, because if you really care about someone

then it shouldnt matter like having to wait.

. . . that is also something that I cannot tell my parents and Id feel more comfortable if they knew what was going on because they are really easy on me.

They will let me go out and they have met my boyfriends and stuff like that,

but that is something that I cant tell them, so that tells me that its not right.

Adolescents stated that their peers, regardless of their race/ethnicity, did

not take physical intimacy and sexual intercourse seriously, viewing it as a

sport or a means to improve ones social status. One 17-year-old boy said:

Well, they will have intimate times. They will have sex. They will get pregnant and then they will ruin their whole life. Thats what I mean, taking

things out of hand and getting pregnant before you get your education, you

ruin your whole life right there, and having sex . . . You are still a minor when

you try to do these things and when you are kind of ignorant at times when

you do things like that.

This same 17-year-old boy eloquently summarized Asian-American

adolescents dating behaviors and sexual attitudes:

So, dont think that Asian kids are those innocent little school kids who stay

home, dont date, does homework everyday, sleeps at 9:00, and wakes up at

6:00 and dont do those dumb things. We are the typical kids, as most kids are.

Discussion

The study findings revealed that 70% of Asian-American adolescents

dated without parental knowledge. This is the first study, to our knowledge,

to examine this issue in Asian-Americans adolescents. Dating without

parental knowledge among adolescents in general has been examined in

few studies (Nguyen, 1998; Wright, 1982). Before obtaining parental

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

108

Journal of Adolescent Research

permission to date, 30% of all high school seniors surveyed dated without

parental knowledge in one study (Wright, 1982). Another study revealed

that some Vietnamese-American young adults dated without parental

knowledge to date partners who did not meet their parents approval

(Nguyen, 1998). Dating without parental knowledge has been associated

with high-risk behaviors, including delinquency and drug use (Wright,

1982). These results suggest the importance of carefully questioning AsianAmerican adolescents about dating without parental knowledge and their

participation in other high-risk behaviors.

A key theme identified in the interviews was the relationship of dating

to education. The emphasis on education, with dating seen as interference,

correlates with traditional normative cultural Asian values (Kim & Ward,

2007; Louie, 2004; Nguyen, 1998; Sung, 1985; Yu, 2007). Adolescent dating has been associated with lower academic achievement (Quatman et al.,

2001). To our knowledge, however, no previous studies have documented

that Asian-American parents frequently avoid acknowledging or discussing

their childrens dating, as long as their children maintain their grades.

Parents silent acceptance of dating could be due to understanding their

childrens desire to be like their peers, or possibly their own changes in

retention of Asian values. One study demonstrated Asian-American parents

strongly endorse traditional values but permit certain Western adolescent

behaviors, such as when and whom to date (Nguyen & Williams, 1989). If

Asian-American parents frequently fail to acknowledge adolescent dating,

is it possible that they may fail to acknowledge other activities, such as drug

or underage alcohol use, if their children are able to maintain high levels of

academic achievement? Clearly, further research is needed in this area.

The dating sequence for many adolescents in this group did not follow

the usual U.S. pattern (Furman & Wehner, 1994; McCabe, 1984). Many

adolescents bypassed casual dating and directly entered a single, steady

relationship. Asian-American adolescents noticed that their dating behavior

differed from peers. To our knowledge, this is the first published account of

this type of dating sequence in Asian-American adolescents. Their immediate progression to serious dating may reflect traditional normative Asian

cultural views that when dating is permitted, it is a serious matter (Kibria,

1993). Involvement in a serious relationship has been shown to be associated with the earlier onset of sexual activity (Cooksey et al., 2002; Davies

& Windle, 2000; Miller, McCoy, & Olson, 1986; Thornton, 1990). Since

Asian-American adolescents often proceed directly from talking to a partner to a single steady relationship, counseling Asian-American adolescents

about the risks of sexual activity and prevention of sexually transmitted

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

Lau et al. / Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents

109

diseases and pregnancy may need to occur prior to the onset of a dating

relationship.

Adolescents with the highest AVS scores were significantly more likely

than those with the lowest scores to date without parental knowledge and

believe sexual intercourse could only occur after a longer period of dating.

Prior research on adherence to Asian values and dating, let alone dating

without parental knowledge, is nonexistent. Our finding of adolescents with

the highest AVS scores dating without parental knowledge is noteworthy.

The association of the highest AVS scores and delayed sexual debut during

dating among Asian-American adolescents is consistent with the large body

of research demonstrating a positive relationship between acculturation and

sexual attitudes in immigrant and American-, Canadian-, or British-born

Asian adolescents (Brotto et al., 2005; Chen & Yang, 1986; Huang & Uba,

1992; Meston, Trapnell, & Gorzalka, 1998). Our studys findings suggest

that clinicians should ask Asian-American adolescents about their dating

practices, especially dating without parental knowledge. Although these

Asian-American adolescents are more likely to believe sexual intercourse

should occur after longer periods of dating, they should be counseled on

safe sexual practices as many Asian-American adolescents proceed directly

to a single steady relationship, and steady dating has been associated with

the earlier onset of sexual activity (Cooksey et al., 2002; Davies & Windle,

2000; Miller, McCoy, & Olson, 1986; Thornton, 1990).

Several study limitations should be noted. Although 52 youths were

approached about participating in the study, only 31 actually completed the

study. To identify a significant difference between two groups (for example,

adolescents who dated with permission and adolescents who dated without

permission), at least 88 participants (44 for each groups) were needed for

this study. This sample size limitation could account for the lack of significant association between AVS scores and several dating behaviors/sexual

attitudes. This study did not examine whether adolescents were first-, second-,

or third-generation Asian-Americans. Participants were recruited from one

Chinese community center, and thus the study population may not be representative of all youth who attended the community center or its surrounding community. Excluding participation of adolescents enrolled in an English

as a Second Language program or who read below an eighth-grade level

may have affected the results of the study by excluding youths who may

have scored higher on the AVS.

In conclusion, the study findings reveal that Asian-American adolescents frequently date without parental knowledge and parental permission.

Adolescents with the highest AVS scores were most likely to date without

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

110

Journal of Adolescent Research

parental knowledge and believe sexual intercourse should occur after a

longer period of dating. Asian-American adolescents also frequently

reported that their parents secretly permit adolescents to date, as long as it

does not interfere with academics. Asian-American adolescents dating progression often differs by skipping intermediate stages and proceeding to a

single steady relationship. Asian-American adolescents should be carefully

questioned by their healthcare providers about dating practices, especially

proceeding to a single steady dating relationship, in order to target riskreduction counseling regarding onset of sexual activity. These study findings could aid clinicians in identifying adolescents at risk of engaging in

high-risk behaviors by virtue of their current dating behaviors, and targeting such at-risk adolescents for early risk-reduction counseling.

References

Abe-Kim, J., Okazaki, S., & Goto, S. G. (2001). Unidimensional versus multidimensional

approaches to the assessment of acculturation for Asian American populations. Cultural

Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 7, 232-246.

Brotto, L. A., Chik, H. M., Ryder, A. G., Gorzalka, B. B., & Seal, B. N. (2005). Acculturation

and sexual function in Asian women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 34, 613-626.

Cauffman, E., & Steinberg, L. (1996). Interactive effects of menarchal status and dating on dieting and disordered eating among adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology, 32, 631-635.

Chan, D. W. (1990). Sex knowledge, attitudes, and experience of Chinese medical students in

Hong Kong. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 19, 73-93.

Chang, J. S., Tsang, A. K. T., Lin, R., & Lui, P. (1997). Premarital sexual mores in Taiwan and

Hong Kong. Journal of Asian and African-American Studies, 31, 265-285.

Chen, C., & Stevenson, H. W. (1995). Motivation and mathematics achievement: A comparative study of Asian-American, Caucasian-American and East Asian high school students.

Child Development, 66, 1215-1234.

Chen, C. L., & Yang, D. C. Y. (1986). The self image of Chinese-American adolescents: A

cross cultural comparison. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 32, 19-26.

Chun, K., Organista, P. B., & Marin, G. (Eds.). (2003). Acculturation: Advances in theory,

measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological

Association.

Cooksey, E. C., Mott, F. L., & Neubauer, S. A. (2002). Friendships and early relationships

linked to sexual initiation among American adolescents born to young mothers.

Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34(3), 118-126.

Davies, P. T., & Windle, M. (2000). Middle adolescents dating pathways and psychosocial

adjustment. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 46, 90-118.

Feldman, S. S., Mont-Reynaud, R., & Rosenthal, D. A. (1992). When East moves West: The

acculturation of values of Chinese adolescents in the US and Australia. Journal of

Research on Adolescence, 2, 147-173.

Feldman, S. S., Turner, R. A., & Araujo, K. (1999). Interpersonal context as an influence on

sexual timetables of youths: Gender and ethnic differences. Journal of Research on

Adolescence, 9, 25-52.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

Lau et al. / Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents

111

Felix-Ortiz, M., Newcomb, M. D., & Myers, H. (1994). A multidimensional measure of cultural identity for Latino and Latina adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences,

16, 99-115.

Fuligni, A. J., & Stevenson, H. W. (1995). Time use and mathematics achievement among

American, Chinese, and Japanese high school students. Child Development, 66, 830-842.

Fuligni, A. J., Tseng, V., & Lam, M. (1999). Attitudes toward family obligations among

American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child

Development, 70, 1030-1044.

Furman, W., & Wehner, E. A. (1994). Romantic views: Toward a theory of adolescent romantic relationships. In R. Montemayor, G. Adams, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Advances in adolescent development (Vol. 6). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social

Problems, 12, 436-445.

Hansen, W. B., Paskett, E. D., & Carter, L. J. (1999). The adolescent sexual activity index

(ASAI): A standardized strategy for measuring interpersonal heterosexual behaviors

among youth. Health Education Research, 14, 485-490.

Huang, K., & Uba, L. (1992). Premarital sexual behavior among Chinese college students in

the United States. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 21, 227-240.

Hynie, M., Lalonde, R. N., & Lee, N. (2006). Parentchild value transmission among Chinese

immigrants to North American: The case of traditional mate preferences. Cultural

Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 12, 230-244.

Ip, W., Chau, J. P. C., Chang, A. M., & Lui, M. H. L. (2001). Knowledge of and attitudes

toward sex among Chinese. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 23, 211-222.

Kibria, N. (1993). Family tightrope: The changing lives of Vietnamese Americans. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kim, B. S. K., Atkinson, D. R., & Yang, P. H. (1999). The Asian Values Scale: Development,

factor analysis, validation and reliability. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46, 342-352.

Kim, B. S. K., & Omizo, M. M. (2003). Asian cultural values, attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help and willingness to see a counselor. The Counseling

Psychologist, 31, 343-361.

Kim, B. S. K., Yang, P. H., Atkinson, D. R., Wolfe, M. M., & Hong, S. (2001). Cultural value

similarities and differences among Asian American ethnic groups. Cultural Diversity and

Ethnic Minority Psychology, 7, 343-361.

Kim, J. L., & Ward, L. M. (2007). Silence speaks volumes. Journal of Adolescent Research,

22, 3-31.

Knox, D., & Wilson, K. (1981). Dating behaviors of university students. Family Relation, 30,

255-258.

Longmore, M. A., Manning, W. D., & Giordano, P. C. (2001). Preadolescent parenting strategies and teens dating and sexual initiation: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Marriage

and Family, 63, 322-335.

Louie, V. (2004). Compelled to excel: Immigration, education and opportunity among Chinese

Americans. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

McCabe, M. P. (1984). Toward a theory of adolescent dating. Adolescence, 73, 159-170.

McDaniel, C. O. (1969). Dating roles and reasons for dating. Journal of Marriage and the

Family, 31, 97-107.

Meier, A. (2003). Adolescents transitions to first intercourse, religiosity and attitudes about

sex. Social Forces, 81, 1031.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

112

Journal of Adolescent Research

Meston, C. M., Trapnell, P., & Gorzalka, B. B. (1998). Ethnic, gender and length of residency

influences on sexual knowledge and attitudes. Journal of Sex Research, 35, 176-188.

Michael, R. T., & Bickert, C. (2001). Exploring determinants of adolescents early sexual

behavior. In R. Michael (ed.), Social awakening: Adolescent behavior as adulthood

approaches (pp. 137-173). New York: Russell Sage.

Miller, B. C., McCoy, J. K., & Olson, T. D. (1986). Dating age and stage as correlates of adolescent sexual attitudes and behavior. Journal of Adolescent Research, 1, 361-371.

Montogomery, M. J., & Sorell, G. T. (1998). Love and dating experience in early and middle

adolescence: Grade and gender comparisons. Journal of Adolescence, 21, 677-689.

Nguyen, L. T. (1998). To date or not to date a Vietnamese: Perceptions and expectations of

Vietnamese American college students. Amerasia Journal, 24, 143-169.

Nguyen, N. A., & Williams, H. L. (1989). Transition from East to West: Vietnamese adolescents and their parents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent

Psychiatry, 28, 505-515.

Phinney, J. S. (1989). Stages of ethnic identity development in minority group adolescents.

Journal of Early Adolescence, 9, 34-49.

Quatman, T., Sampson, K., Robinson, C., & Watson, C. M. (2001). Academic, motivational

and emotional correlates of adolescent dating. Genetic, Social and General Psychology

Monographs, 127, 211-235.

Reglin, G. L., & Adams, D. R. (1990). Why Asian-American high school students have higher

grade point averages and SAT scores than other high school students. High School Journal,

73, 143-149.

Roche, J. P. (1986). Premarital sex: Attitudes and behavior by dating stage. Adolescence, 21,

107-121.

Skipper, J. K., & Nass, G. (1966). Dating behavior: A framework for analysis and an illustration. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 28, 412-420.

Sung, B. L. (1985). Bicultural conflicts in Chinese immigrant children. Journal of

Comparative Family Studies, 16, 255-269.

Tang, S., & Zuo, J. (2000). Dating attitudes and behaviors of American and Chinese college

students. Social Science Journal, 37, 67-78.

Thornton, A. (1990). The courtship process and adolescent sexuality. Journal of Family Issues,

11, 239-273.

Violato, C., & Kwok, D. (1995). A cross-cultural validation of a four-factor model of adolescent concerns: A confirmatory factor analysis based on a sample of Hong Kong Chinese

adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 18, 607-617.

Wright, L. S. (1982). Parental permission to date and its relationship to drug use and suicidal

thoughts among adolescents. Adolescence, 66, 409-418.

Yu, J. (2007). British born Chinese teenagers: The influence of Chinese ethnicity on their attitudes towards sexual behavior. Nursing and Health Sciences, 9, 69-75.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Siebenbruner, J., & Collins, W. A. (2001). Diverse aspects of dating:

Associations with psychosocial functioning from early to middle adolescence. Journal of

Adolescence, 24, 313-336.

May Lau, MD, MPH, is an assistant professor in the Division of General Pediatrics at the

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and an adolescent medicine specialist at

Childrens Medical Center, both in Dallas, Texas. Her research interests include racial/ethnic

and reproductive health issues.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

Lau et al. / Dating and Sexual Attitudes in Asian-American Adolescents

113

Christine Markham, PhD, is deputy director of the University of Texas Prevention Research

Center and assistant professor of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences at the University

of Texas School of Public Health in Houston, Texas. She has more than 15 years of experience

in adolescent sexual and reproductive health.

Hua Lin, PhD, is a biostatistical consultant in the Division of General Pediatrics at the

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Her PhD is in health economics, and her

research interest is in racial disparities in health status and care.

Glenn Flores, MD, is professor of pediatrics and public health, director of the Division of

General Pediatrics, the Judith and Charles Ginsburg Chair in Pediatrics, and the director of the

Academic General Pediatrics Fellowship at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical

Center and Childrens Medical Center, both in Dallas, Texas. His research interests include

racial/ethnic disparities in childrens health and health care, community-based interventions

for improving the health and healthcare of underserved children, insuring uninsured children,

testing innovative interventions for chronic disease management, and linguistic and cultural

issues in healthcare.

Mariam R. Chacko, MD, is medical director of the Baylor Teen Health Clinics and professor of pediatrics in the Section of Adolescent Medicine & Sports Medicine, Baylor College of

Medicine, Houston, Texas. She has 24 years of clinical and research experience in adolescents

and young adult reproductive health issues.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UT SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CTR on July 12, 2013

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Substance Abuse Counseling Complete 5th EditionDocument379 pagesSubstance Abuse Counseling Complete 5th Editionnintendoagekid86% (59)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- HANDBOOK-McLean-and-Syed-2015-The Oxford Handbook of Identity Development PDFDocument625 pagesHANDBOOK-McLean-and-Syed-2015-The Oxford Handbook of Identity Development PDFEsp Success Beyond100% (13)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Baseline Risk Assessment and Risk Matrix (An Example)Document8 pagesBaseline Risk Assessment and Risk Matrix (An Example)Victor75% (4)

- CS Ai 1617PSDocument2 pagesCS Ai 1617PSlauravbleedioteNo ratings yet

- Coriolis AccelerationDocument6 pagesCoriolis AccelerationlauravbleedioteNo ratings yet

- EE40LX Robot Schematic: Left Motor Right MotorDocument1 pageEE40LX Robot Schematic: Left Motor Right MotorlauravbleedioteNo ratings yet

- Willpower GratificationDocument2 pagesWillpower GratificationTH_2014No ratings yet

- Vocab From New York TimesDocument1 pageVocab From New York TimeslauravbleedioteNo ratings yet

- Asian American Women - Sexual HealthDocument18 pagesAsian American Women - Sexual HealthlauravbleedioteNo ratings yet

- SS K - 12 Online Textbook AccessDocument7 pagesSS K - 12 Online Textbook AccesslauravbleedioteNo ratings yet

- Ex A Me 2010Document4 pagesEx A Me 2010Megagab99No ratings yet

- CMS Canadian Open Math ChallengeDocument4 pagesCMS Canadian Open Math ChallengelauravbleedioteNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Feeding and Swallowing Difficulties in PDFDocument118 pagesThe Nature of Feeding and Swallowing Difficulties in PDFLisa NurhasanahNo ratings yet

- Vector and Pest Control in DisastersDocument10 pagesVector and Pest Control in DisastersTaufik RizkiandiNo ratings yet

- Dr. Banis' Psychosomatic Energetics Method for Healing Health ConditionsDocument34 pagesDr. Banis' Psychosomatic Energetics Method for Healing Health ConditionsmhadarNo ratings yet

- English in Nursing 1: Novi Noverawati, M.PDDocument11 pagesEnglish in Nursing 1: Novi Noverawati, M.PDTiara MahardikaNo ratings yet

- Schedule - Topnotch Moonlighting and Pre-Residency Seminar Nov 2022Document2 pagesSchedule - Topnotch Moonlighting and Pre-Residency Seminar Nov 2022Ala'a Emerald AguamNo ratings yet

- Sir 2014 SouthamericaDocument33 pagesSir 2014 SouthamericahusseinNo ratings yet

- RecormonDocument36 pagesRecormonShamal FernandoNo ratings yet

- My Good Habits - Welcome Booklet 2 - 1Document17 pagesMy Good Habits - Welcome Booklet 2 - 1lisa_ernsbergerNo ratings yet

- Corn SpecDocument4 pagesCorn SpecJohanna MullerNo ratings yet

- Marriage and Later PartDocument25 pagesMarriage and Later PartDeepak PoudelNo ratings yet

- Anand - 1994 - Fluorouracil CardiotoxicityDocument5 pagesAnand - 1994 - Fluorouracil Cardiotoxicityaly alyNo ratings yet

- TOFPA: A Surgical Approach To Tetralogy of Fallot With Pulmonary AtresiaDocument24 pagesTOFPA: A Surgical Approach To Tetralogy of Fallot With Pulmonary AtresiaRedmond P. Burke MD100% (1)

- Abc Sealant SDSDocument5 pagesAbc Sealant SDSKissa DolautaNo ratings yet

- Bionics: BY:-Pratik VyasDocument14 pagesBionics: BY:-Pratik VyasHardik KumarNo ratings yet

- Advances and Limitations of in Vitro Embryo Production in Sheep and Goats, Menchaca Et Al., 2016Document7 pagesAdvances and Limitations of in Vitro Embryo Production in Sheep and Goats, Menchaca Et Al., 2016González Mendoza DamielNo ratings yet

- Taking Blood Pressure CorrectlyDocument7 pagesTaking Blood Pressure CorrectlySamue100% (1)

- What Is Drug ReflectionDocument8 pagesWhat Is Drug ReflectionCeilo TrondilloNo ratings yet

- Charakam Sidhistanam: Vamana Virechana Vyapat SidhiDocument45 pagesCharakam Sidhistanam: Vamana Virechana Vyapat Sidhinimisha lathiffNo ratings yet

- Safe Haven Thesis StatementDocument5 pagesSafe Haven Thesis Statementangelabaxtermanchester100% (2)

- Dukungan Nutrisi Pra / Pasca BedahDocument22 pagesDukungan Nutrisi Pra / Pasca BedahAfdhal Putra Restu YendriNo ratings yet

- Ayurveda Medical Officer 7.10.13Document3 pagesAyurveda Medical Officer 7.10.13Kirankumar MutnaliNo ratings yet

- Venus Technical Data Sheet of V-2400 Series RespiratorDocument7 pagesVenus Technical Data Sheet of V-2400 Series RespiratorPrabhu Mariadoss SelvarajNo ratings yet

- From Solidarity To Subsidiarity: The Nonprofit Sector in PolandDocument43 pagesFrom Solidarity To Subsidiarity: The Nonprofit Sector in PolandKarimMonoNo ratings yet

- Reactive Orange 16Document3 pagesReactive Orange 16Chern YuanNo ratings yet

- Siddhant Fortis HealthCareDocument4 pagesSiddhant Fortis HealthCaresiddhant jainNo ratings yet

- REAL in Nursing Journal (RNJ) : Penatalaksanaan Pasien Rheumatoid Arthritis Berbasis Evidence Based Nursing: Studi KasusDocument7 pagesREAL in Nursing Journal (RNJ) : Penatalaksanaan Pasien Rheumatoid Arthritis Berbasis Evidence Based Nursing: Studi Kasustia suhadaNo ratings yet

- HRFuture Sept 2020 MJLKJDocument59 pagesHRFuture Sept 2020 MJLKJGlecy KimNo ratings yet